What is chondroitin

Chondroitin is a major component of cartilage that helps it retain water. Chondroitin sulfate is made by the body naturally and it is found in human cartilage, bone, cornea, skin, and arterial wall. Chondroitin sulfate belongs to a family of heteropolysaccharides called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). For production of nutritional supplements, chondroitin can be manufactured from cartilage of animals, like cows, pigs or sharks (such bovine trachea, pork byproducts, shark cartilage, and whale septum) or it can be made in the laboratory 1. Chondroitin supplement is sold as chondroitin sulfate. In many European countries chondroitin is approved as a prescription treatment for osteoarthritis. In the U.S., chondroitin is often combined with a glucosamine supplement. Chondroitin is an over-the-counter nutritional supplement made primarily of chondroitin sulfate. Chondroitin is said to work by stopping the degradation of cartilage and restoring lost cartilage in osteoarthritic joints. Chondroitin also contains sulfur-containing amino acids, which are essential building blocks for cartilage molecules in the human body.

Chondroitin sulfate has been studied for the treatment of osteoarthritis; however, information on its effectiveness is conflicting. Chondroitin is commonly given in combination with other agents, such as glucosamine sulfate or glucosamine hydrochloride.

The largest study to date, the 2006 Glucosamine/chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) looked at 1,600 people with knee osteoarthritis 2. The first phase found that a small subset of patients with moderate-to-severe arthritis experienced significant pain relief from combined glucosamine and chondroitin. The 2008 phase found that glucosamine and chondroitin, together or alone, did not slow joint damage. And in the two-year-long 2010 phase, glucosamine and chondroitin were found as effective for knee osteoarthritis as celecoxib (Celebrex).

But a 2010 meta-analysis of 10 trials involving more than 3,000 patients published in BMJ found no benefit from chondroitin, glucosamine or both.

A separate 2011 study showed a significant improvement in pain and function in patients with hand osteoarthritis using chondroitin alone. Benefits of chondroitin and glucosamine remain controversial, but the supplements appear extremely safe.

A 2015 Cochrane Systematic review 3 of randomized trials of mostly low quality reveals that chondroitin (alone or in combination with glucosamine) was better than placebo in improving pain in participants with osteoarthritis in short-term studies. The benefit was small to moderate with an 8 point greater improvement in pain (range 0 to 100) and a 2 point greater improvement in Lequesne’s index (a combination index of pain and physical function, indicating quality of life, range 0 to 24), both likely clinically meaningful. These differences persisted in some sensitivity analyses and not others. Chondroitin had a lower risk of serious adverse events compared with control. More high-quality studies are needed to explore the role of chondroitin in the treatment of osteoarthritis. The combination of some efficacy and low risk associated with chondroitin may explain its popularity among patients as an over-the-counter supplement.

Osteoarthritis is a disease of the joints, such as the knee or hip. When the joint loses cartilage, the bone grows to try to repair the damage, but this bone growth may make the situation worse. This can make the joint painful and unstable, which can affect physical function or ability to use the joint. Osteoarthritis is the most common of all joint disorders and it is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States 4. Pathologically, osteoarthritis is characterized by softening and degeneration of articular cartilage, formation of new bone at joint margins, and capsular fibrosis. Clinically, osteoarthritis manifests as joint pain, stiffness, deformity, and loss of function. Clinical and radiographic surveys have found that the prevalence of osteoarthritis increases with age, from 1% in people < 30 years to 10% in those < 40 years to more than 50% in individuals > 60 years of age 5:42-50.)). Autopsy studies show cartilage changes in almost all people above 65 years of age 6. Osteoarthritis is equally common in men and women between 45 and 55 years but is more common in women after 55 years of age 7. Risk factors for osteoarthritis include obesity, joint dysplasia (abnormal anatomy of the joint due to abnormal growth), trauma, occupational activity, and family history, among others 8. Osteoarthritis is classified as primary or secondary based on the absence or presence of anteceding joint abnormality or injury. Primary osteoarthritis is further classified as generalized or localized to a joint area such as hand, knee, hip, spinal apophyseal joints (between spinal bones/vertebrae), and foot, or to other joints (shoulder, elbow, wrist, and ankle) 8.

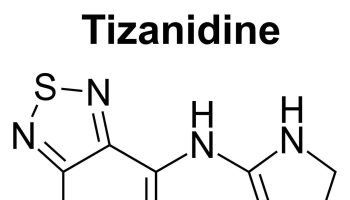

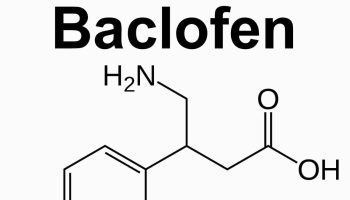

Treatment of osteoarthritis is primarily directed at relieving pain and improving functional status. Various treatment options are available for patients with osteoarthritis, including the following: (1) oral medications: analgesics such as acetaminophen, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and opioids 9; (2) local therapies (applied as gels or creams): topical NSAIDs and capsaicin; (3) intra-articular therapies: corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid injections 10; (4) nonpharmacologic methods: physical therapy, aerobic therapy, strengthening exercises, transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation, and wedged insoles 11; and (5) surgical treatments: joint replacement and arthroscopic debridement of the affected joint 12. However, frequent side effects, limited efficacy, and variable rates of success limit the use of many non-surgical treatments.

Key points on the effectiveness of several treatments for osteoarthritis of the knee 13:

- Home-based exercise programs and tai chi show short- to medium-term benefits for symptoms (primarily pain, function, and quality of life) but lack data on long-term benefits.

- Acupuncture is safe and may provide pain relief for some patients with osteoarthritis.

- Strength and resistance training, pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation show mostly short-term benefits, whereas agility training shows short- and long-term benefits.

- Weight loss and general exercise programs show medium- and longterm benefits.

- Intra-articular platelet-rich plasma, balneotherapy, and whole body vibration show medium-term benefits.

- Glucosamine-chondroitin and glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate alone show medium-term benefits with no long-term benefits for pain or function.

Over the past few years, various nutritional supplements, including chondroitin, glucosamine, avocado/soybean unsaponifiables, and diacerein, have emerged as new treatment options for osteoarthritis 14. These supplements are characterized by both slow onset of action over six to eight weeks and a carryover of effect for up to two months after withdrawal 15. According to recent recommendations from the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism, drugs for treatment of osteoarthritis are classified as symptom-modifying or structure-modifying drugs, depending on their capacity to interfere with disease progression 16. The current body of evidence suggests that chondroitin falls into the symptom-modifying category (i.e., chondroitin has a primary effect on improvement of pain and function), and glucosamine and diacerein into the structure-modifying category 17 (i.e., they have an effect on progression of arthritis, such as an effect on joint space narrowing as assessed by radiography of the involved joint). One of the main proposed advantages of these medications over traditional medical therapies is their safety profile.

Before trying a complementary therapy, make sure you understand whether the benefits have been clearly proven so that you are not misled or given false hope. The current reliable evidence from studies of complementary therapies for arthritis is summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Complementary therapies for arthritis

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | |

| Strong evidence | • Fish oils | |

| Moderate evidence* | • Acupuncture (knee OA) • Avocado-soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) • Ginger • Green-lipped mussel • Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata) • Phytodolor • Pine bark extracts • Rosehip • S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) | • Gamma linoleic acid (found in evening primrose oil, borage/starflower seed oil and blackcurrant seed oil) |

| Limited evidence# | • Acupuncture (hip OA) • Chinese herbal patches containing FNZG or SJG • Chondroitin^ • Devil’s claw • Fish oils • Glucosamine sulphate^ • Krill oil • SJG • SKI 306X • Turmeric • Vitamins A, C, E • Vitamin B Complex • Will bark extract | • Acupuncture • Krill oils • Phytodolor |

Footnotes:

*Promising results from multiple studies but still some doubts about effectiveness

# Positive result from a single study but there are important doubts about whether it works

^ Multiple studies have been done but results are conflicting and there are still doubts about the effectiveness of these supplements

(Note: there are many other treatments available however these have not been demonstrated to be safe and/or effective. There is also no reliable proof that complementary therapies are effective for any other types of arthritis.)

Warning signs

Be on the lookout for the following warning signs when considering a new treatment:

- A cure is offered. There is currently no cure for most forms of arthritis so be wary of products or treatments that promise a cure.

- Proof for the treatment relies only on testimonials (personal stories). This may be a sign that the treatment has not been scientifically tested.

- You are told to give up your current effective treatments or discouraged from getting treatment from your doctor.

- The treatment is expensive and not covered by your health insurance.

Before you start using a complementary therapy

Here are a few steps to protect yourself:

- Get an accurate diagnosis from your doctor

- Get information about the treatment. Talk to your doctor about the treatment. Find out if the treatment is likely to interact with your current treatments.

- Do not stop any current treatments without first discussing it with your doctor. You could also talk to your pharmacist or local Arthritis Office about the treatment. Keep in mind that the information given to you by the person promoting the product or therapy may not be reliable, or they may have a financial incentive to recommend a specific treatment.

- Keep in mind that the information given to you by the person promoting the product or therapy may not be reliable, or they may have a financial incentive to recommend a specific treatment.

- Make sure the treatment or therapy is something you can afford, particularly if you need to keep using it.

- Check qualifications of practitioners involved. The websites of some professional associations are listed below for more information or to help you find an accredited practitioner.

Working with your healthcare team

You may feel concerned that your doctor or other members of your healthcare team will disapprove of complementary therapies. However it is very important to keep your healthcare team informed, even if they do not approve. Your healthcare team, particularly your doctor and pharmacist, can’t give you the best professional advice without knowing all the treatments you are using. This includes vitamin supplements, herbal medicines and other therapies.

Chondroitin sulfate in osteoarthritis

Proposed mechanisms of action of chondroitin sulfate supplement include restoring the extracellular matrix of cartilage, preventing further cartilage degradation 18, and overcoming a dietary deficiency of sulfur-containing amino acids, which are essential building blocks for cartilage extracellular matrix molecules 19. A large number of patients with osteoarthritis in the United States and around the world are already using chondroitin alone or in combination with glucosamine for relief of osteoarthritis-related joint pain. Both glucosamine and chondroitin are available over the counter as nutritional supplements, and combination therapy of glucosamine and chondroitin has been used, but it is unclear whether these two supplements produce an additive or a synergistic effect.

Chondroitin may provide additional pain relief for some people with knee and hand osteoarthritis. The benefit is usually modest (about 8 to 10 percent improvement) and it works slowly (up to 3 months). Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, which has rated and evaluated more than 80,000 natural drug ingredients and commercial dietary supplements, classified chondroitin as “possibly effective” for knee osteoarthritis.

A 2011 study published in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism found chondroitin sulfate to modestly relieve pain and improve function in people with hand osteoarthritis (the results of this study were not yet taken into account by the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database for their recommendation). The supplement was made from fish and taken daily at a dose of 800 mg for 6 months. Patients reported some improvement after 3 months of treatment. A shorter duration of morning stiffness was also noticed. Chondroitin did not improve grip strength. In addition, patients treated with chondroitin did not use less pain medication (acetaminophen) than those taking placebo.

Because no side effects due to chondroitin were reported, it can be tried as an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for patients who cannot take NSAIDs and who need long-term treatment. Chondroitin and NSAIDs have not been compared head-to-head; however, other studies of NSAIDs in patients with hand osteoarthritis showed a similar improvement in hand pain and function as found with chondroitin. The NSAIDs relieve pain more rapidly than chondroitin sulfate, but they may cause more serious side effects (increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, heart attack or stroke, and interactions with other medications), particularly in elderly patients.

Glucosamine in osteoarthritis

Glucosamine is a natural compound found in healthy cartilage, particularly in the fluid around the joints. For dietary supplements, glucosamine is harvested from shells of shellfish such as crab, lobster or shrimp shells or can be made in the laboratory. Glucosamine can come in several chemical forms, including glucosamine sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride and N-acetyl glucosamine, but the one most used in arthritis is glucosamine sulfate. These supplements are not considered interchangeable. In laboratory tests, glucosamine showed anti-inflammatory properties and even appeared to help cartilage regeneration.

People use glucosamine sulfate orally to treat a painful condition caused by the inflammation, breakdown and eventual loss of cartilage (osteoarthritis).

What does the research say?

Glucosamine sulphate

- Pain: opinion is divided about the effectiveness of glucosamine sulfate on pain. In some studies, glucosamine improved pain from OA of the knee more than placebo (fake pills). However in other studies, pain improved about the same whether people took glucosamine or placebo.

- Cartilage: there is some evidence that glucosamine sulfate can slow cartilage breakdown in the knee.

Glucosamine hydrochloride

- Studies suggest the hydrochloride form is not effective in relieving pain. The effect of glucosamine hydrochloride on cartilage has not been tested.

Research on glucosamine use for specific conditions shows:

- Osteoarthritis. Oral use of glucosamine sulfate might provide some pain relief for people with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip or spine.

- Rheumatoid arthritis. Early research suggests that oral use of glucosamine hydrochloride might reduce pain related to rheumatoid arthritis when compared with placebo, an inactive substance. However, researchers didn’t see an improvement in inflammation or the number of painful or swollen joints.

When considering glucosamine, read product labels carefully to make sure you choose the correct form. While glucosamine sulfate has been studied for treatment of arthritis, there’s no clinical evidence to support the use of N-acetyl glucosamine in treating arthritis.

Glucosamine may provide modest pain relief for some patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip and spine. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database classified glucosamine as “likely effective” for osteoarthritis, thus rating it higher than chondroitin. Most of the studies included in the recommendation were done in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Because glucosamine is very safe, it can be tried in place of NSAIDs in patients who need long-term treatment and cannot take NSAIDs.

However, some studies show that glucosamine provides the same pain relief as a placebo (a pill that does not contain any medicine). This is called a “placebo effect,” in which the patients expect to feel better, so they do. An example is a study published in 2010 in the Journal of the American Medical Association that found glucosamine did not provide additional pain relief compared to placebo in people with chronic lower back pain caused by osteoarthritis in the lower spine. Half of the participants took glucosamine (1,500 milligrams daily) and the other half took a placebo. Both groups said their lower back pain improved by about 50 percent over one year. However, due to small number of people involved in the study, more research is needed to confirm these results for lower spine osteoarthritis.

Glucosamine sulfate might provide pain relief for people with osteoarthritis. The supplement appears to be safe and might be a helpful option for people who can’t take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). While study results are mixed, glucosamine sulfate might be worth a try.

Glucosamine safety and side effects

When taken in appropriate amounts, glucosamine sulfate appears to be safe. Oral use of glucosamine sulfate can cause:

- Nausea

- Heartburn

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Drowsiness

- Skin reactions

- Headache

Because glucosamine products might be derived from the shells of shellfish, there is concern that the supplement could cause an allergic reaction in people with shellfish allergies.

Glucosamine might worsen asthma.

It’s possible that glucosamine sulfate might affect your blood sugar levels, which might interfere with blood sugar control during and after surgery. Stop taking glucosamine sulfate two weeks before an elective surgery.

Glucosamine Drug Interactions

Possible interactions include:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol, others). Taking glucosamine sulfate and acetaminophen together might reduce the effectiveness of both the supplement and medication.

- Warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven). Taking glucosamine alone or in combination with the supplement chondroitin might increase the effects of the anticoagulant warfarin. This can increase your risk of bleeding.

Chondroitin and glucosamine

Chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine are popular supplements used to treat the pain and loss of function associated with osteoarthritis. However, most studies assessing their effectiveness show modest to no improvement compared with placebo in either pain relief or joint damage.

The most comprehensive long-term study of any supplement—the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT) 20 —looked at the combination of chondroitin and glucosamine, both supplements individually, celecoxib (Celebrex) and placebo in patients with knee osteoarthritis.

The first phase of GAIT found that the combination of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate showed significant relief in a smaller subgroup of study participants with moderate-to-severe knee pain. But there was no effect in the group with mild pain. Those results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2006.

The doses used in GAIT were based on the doses seen in the prevailing scientific literature

- Glucosamine alone: 1500 mg daily given as 500 mg three times a day

- Chondroitin sulfate alone: 1200 mg daily given as 400 mg three times a day

- Glucosamine plus chondroitin sulfate combined: same doses-1500 mg and 1200 mg daily

- Celecoxib: 200 mg daily

- Acetaminophen: participants were allowed to take up to 4000 mg (500 mg tablets) per day to control pain, except for the 24 hours before pain was assessed.

What were the key results of the GAIT study?

Researchers found that:

- Participants taking the positive control, celecoxib, experienced statistically significant pain relief versus placebo—about 70 percent of those taking celecoxib had a 20 percent or greater reduction in pain versus about 60 percent for placebo.

- Overall, there were no significant differences between the other treatments tested and placebo.

- For a subset of participants with moderate-to-severe pain, glucosamine combined with chondroitin sulfate provided statistically significant pain relief compared with placebo—about 79 percent had a 20 percent or greater reduction in pain versus about 54 percent for placebo. According to the researchers, because of the small size of this subgroup these findings should be considered preliminary and need to be confirmed in further studies.

- For participants in the mild pain subset, glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate together or alone did not provide statistically significant pain relief.

How many people participated in the study and who were they?

A total of 1,583 people participated in the study. People age 40 or older with knee pain and documented x-ray evidence of osteoarthritis were eligible to participate. Participants could not have used glucosamine for 3 months and chondroitin sulfate for 6 months prior to entering the study. Participants were about 59 years of age, on average, and nearly two-thirds of participants were women. Of the 1,583 study participants, 78 percent (1,229) were in the mild pain subgroup and 22 percent (354) were in the moderate-to-severe pain subgroup.

Were there any side effects from the treatments?

There were 77 reports of serious adverse effects during the study. Of those 77, only 3 were attributed to study treatments. Most side effects were mild, such as upset stomach, and were spread evenly across the different treatment groups. In addition, although GAIT was not designed to evaluate these risks, no change in glucose tolerance was seen for glucosamine nor was an increased incidence of cardiovascular events seen with celecoxib.

The second phase of the GAIT study published in the journal Arthritis and Rheumatism in 2008 looked at preventing joint damage in the knee. The combination of glucosamine and chondroitin appeared to be no more effective at preventing joint damage caused by osteoarthritis than a placebo. While the differences between the groups were not statistically significant, the participants who lost the least amount of joint space over two years were in the groups taking either glucosamine alone or chondroitin alone. It is possible that taking the two supplements together might limit their absorption into the body, explaining the lower effect of the supplement combination.

In the third phase of the GAIT study looking at a total of four years, the supplements in combination or alone had no greater benefit in knee pain relief than celecoxib or placebo. Although the results were not statistically significant, celecoxib achieved the highest odds of attaining at least 20% reduction in pain. These results were published in 2010 in the journal Annals of Rheumatic Disease.

Summary

The American College of Rheumatology in their latest osteoarthritis treatment recommendations published in 2017 does not recommend chondroitin or glucosamine for the initial treatment of osteoarthritis 21. Chondroitin and glucosamine supplements alone or in combination may not work for everyone with osteoarthritis. However, patients who take these supplements and who have seen improvements with them should not stop taking them. Both supplements are safe to take long-term.

The differences in effectiveness of chondroitin may also be caused by variations in dosing and quality of the supplements. The chondroitin content between different brands can vary a lot. Similar concerns have been raised over glucosamine supplements. Talk with your doctor or pharmacist about which brand to choose when trying out either of these supplements, or a combination product.

Should people with osteoarthritis use glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate?

People with osteoarthritis should work with their health care provider to develop a comprehensive plan for managing their arthritis pain: eat right, exercise, lose excess weight, and use proven pain medications. If people have moderate-to-severe pain, they should talk with their health care provider about whether glucosamine plus chondroitin sulfate is an appropriate treatment option.

Glucosamine and chondroitin dosage

Chondroitin capsules, tablets and powder: 800 mg to 1,200 mg daily in two to four divided doses.

Often combined with glucosamine.

Allow up to one month to notice effect.

What is the recommended dose?

- Glucosamine sulfate: 1500mg per day

- Glucosamine hydrochloride: 1500mg per day (note, glucosamine sulfate is suggested to be more effective)

- Chondroitin sulfate: 800 – 1000mg per day

Different brands contain different amounts of glucosamine and chondroitin. Read the label carefully to see how many tablets you need to take to get the right dose or ask your pharmacist for advice.

How long will it take to notice an effect?

You may need to take the supplements for four to six weeks before you notice any improvement. If there is no change in your symptoms by then, it’s likely the supplements will not be of benefit for you and it’s advisable you talk to your doctor about other ways of managing your arthritis.

Precautions

Some chondroitin tablets may contain high levels of manganese, which could be problematic with long-term use. Because chondroitin is made from bovine products, there is the remote possibility of contamination associated with mad cow disease. Chondroitin taken with blood-thinning medication like NSAIDs may increase the risk of bleeding. If you are allergic to sulfonamides, start with a low dose of chondroitin sulfate and watch for any side effects. Other side effects include diarrhea, constipation and abdominal pain.

What are glucosamine possible risks?

- Shellfish allergy: most glucosamine supplements are made from shellfish although some made from non-shellfish sources are now available. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist, before taking it, about whether the supplement is safe for you.

- Bleeding: people taking the blood thinning medicine warfarin should talk to their doctor before starting, stopping or changing their dose of glucosamine as it may interact with warfarin and make the blood less likely to clot.

- Diabetes: glucosamine is a type of sugar so check with your doctor before taking glucosamine if you have diabetes.

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women: there have not been enough long term studies to clearly say that glucosamine is safe for a developing baby. Pregnant women should talk to their doctor before taking glucosamine.

- Other side effects: upset stomach (for example, diarrhoea), headaches, and skin reactions. Talk to your doctor or pharmacist about possible side effects before taking glucosamine.

Chondroitin

- Bleeding: people taking blood thinning medicines, such as warfarin, should talk to their doctor before taking chondroitin as it may increase the risk of bleeding.

- Other side effects: chondroitin may also occasionally cause stomach upsets.

Chondroitin side effects

Applies to chondroitin: oral capsule. Potential adverse reactions associated with chondroitin sulfate include alopecia, constipation, diarrhea, epigastralgia, extrasystoles, eyelid edema, lower limb edema, and skin symptoms 22. Chondroitin sulfate may also exacerbate asthma 23.

Get emergency medical help if you have signs of an allergic reaction: hives; difficult breathing; swelling of your face, lips, tongue, or throat.

Although not all side effects are known, chondroitin is thought to be possibly safe when taken for up to 6 years.

Stop using chondroitin and call your healthcare provider at once if you have:

- irregular heartbeats; or

- swelling in your legs.

Common side effects may include:

- nausea, diarrhea, constipation;

- mild stomach pain;

- hair loss; or

- puffy eyelids.

Asthma exacerbation

Chondroitin supplementation may exacerbate asthma. One study examined bronchial biopsies from patients with atopic asthma in comparison with controls and found that chondroitin sulfate deposits were increased in patients suffering from asthma compared with the controls. Additionally, proteoglycan deposition in the airways appears to be associated with airway responsiveness in patients with asthma 24. One case study describes a 52-year-old woman with long-standing intermittent asthma who reported increased shortness of breath and wheezing with increased use of albuterol. The albuterol was ineffective in relieving symptoms. At this visit, she was given a tapered dose of oral steroids. However, her condition fluctuated over the following 3 weeks despite treatment with steroids and albuterol use. During a follow-up visit, her medical history was reviewed in detail, and it was determined that her symptoms emerged when she began taking a glucosamine 500 mg/chondroitin supplement 400 mg 3 times daily for arthritis. She was advised to discontinue therapy, and within 24 hours, her symptoms disappeared. The patient refused a rechallenge with the agent. Later, the patient reported an episode of wheezing during graduate school when she was involved in a shark dissection. Given that chondroitin sulfate is a constituent of shark cartilage, this could explain this patient’s exacerbation of asthma 23.

Prostate cancer

Current research suggests that increased chondroitin sulfate levels are associated with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) failures for patients treated with surgery for localized prostate cancer. PSA failures are defined as a return to measurable PSA levels following a postsurgical level below the assay threshold or an increase in PSA levels for patients with detectable levels following surgery 25. Supplementation with chondroitin sulfate does not appear to be associated with prostate cancer. However, men with prostate cancer or those at risk for this disease should avoid supplementation until further evidence is discovered.

This is not a complete list of side effects and others may occur. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects.

What is MSM supplement

MSM is the acronym for Methylsulfonylmethane. Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) is the oxidised form of dimethyl sulfoxide. It is found in very low amounts in fruits, corn, tomatoes, tea, coffee, and milk 26. Methylsulfonylmethane and dimethyl sulphoxide are two related nutritional supplements used for symptomatic relief of osteoarthritis 27. Prior to being used as a clinical application, MSM primarily served as a high-temperature, polar, aprotic, commercial solvent, as did its parent compound, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) 28.

MSM is broadly expressed in a number of fruit, vegetable and grain crops, though the extent of MSM bioaccumulation is dependent upon the plant. Alternatively, synthetically produced MSM is manufactured through the oxidation of DMSO with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and purified by either crystallization or distillation. While distillation is more energy intensive, it is recognized as the preferred method 29. Biochemically, this manufactured MSM would have no detectable structural or safety differences from the naturally produced product 30. Since the concentration of MSM is in the hundredths ppm in food sources, synthetically produced MSM makes it possible to ingest bioactive quantities without having to consume unrealistic amounts of food.

Exogenous sources of MSM are introduced into the body through supplementation or consumption of foods like fruits, vegetables, grains, beer, port wine, coffee, tea, and cow’s milk. Along with MSM, absorbed methionine, methanethiol, DMS, and DMSO can be used by the microbiota to contribute to the MSM aggregate within the mammalian host 31. Diet-induced microbiome changes have been shown to affect serum MSM levels in rats 32 and gestating sows 33. That said, the gut flora is readily manipulated by diet, exercise or other factors and likely affects bioavailable MSM sources, as suggested in pregnancy 34.

Osteoarthritis is the most common of all joint disorders and affects over 30 million people in the US and 1 in 10 people aged 35–75 in the UK 35 and is associated with pain and functional disability, which in turn leads to reduced quality of life and increased risk of further morbidity and mortality 36. The treatment of osteoarthritis is largely symptomatic and includes analgesics, NSAIDs as well as exercise and surgical intervention 37.

Two nutritional supplements, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, an organic form of sulfur commercially prepared from lignin) and its oxidized form, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM, occurring in green plants fruits and vegetables) have been used to treat arthritic conditions 38. DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) is converted in the body to MSM (methylsulfonylmethane) and as MSM remains in the body for longer than DMSO 39, it is suggested that many of the beneficial effects of DMSO are due to the long lasting fraction of DMSO which is converted to MSM 40. Both have similar pharmacological properties and their putative effects and mechanisms have been reviewed previously [MSM 41; DMSO 42]. In a 12-week double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial on knee osteoarthritis, 500 mg of MSM three times a day, used alone or in combination with 500 mg of glucosamine three times a day, significantly improved a Likert scale of pain and Lequesne functional index 43. The combination of both ingredients was not more efficacious than each ingredient used alone. In a second 12-week double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial on knee osteoarthritis, 3 g of MSM given twice daily was more efficient than placebo in decreasing Western Ontario and McMaster universities (WOMAC) pain index and functional scores 44.

MSM and DMSO have been reported to reduce peripheral pain 45, inflammation 46 and arthritis 47, and might inhibit the degenerative changes occurring in osteoarthritis 48. These compounds may act through their ability to stabilize cell membranes, slow or stop leakage from injured cells and scavenge hydroxyl free radicals which trigger inflammation 49. Their sulfur content may also rectify dietary deficiencies of sulfur improving cartilage formation 50.

MSM is used orally and topically. Like DMSO, the treatment duration for osteoarthritis is at least three months. The optimum dosage has not been clearly defined as no dose ranging studies have been carried out 27. As a Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status by the Food and Drug Administration in 2007 51, MSM is well-tolerated by most individuals at dosages of up to four grams daily, with few known and mild side effects 52. The suggested oral therapeutic doses is 4–6 g per day 53, although doses of up to 20 g/day have also been used 54; over the counter preparations are typically 1–5 g daily. There is limited formal safety data and no long term assessment. However, MSM is rapidly excreted from the body and animal toxicity studies of MSM showed only minor adverse events using doses of 1.5 g/kg and 2.0 g/kg of MSM for 90 days. This dose represents a human dose of 105–140 g/day, which is equivalent to 17–23 times the proposed maximum recommended human dose of 6 g/day 55. A further study confirmed MSM had no toxic effects on either pregnant rats or their foetus 56. Only minor adverse effects are associated with MSM administration in humans and include allergy, gastrointestinal upsets and skin rashes 57.

MSM supplement benefits

Due to its enhanced ability to penetrate membranes and permeate throughout the body, the full mechanistic function of MSM may involve a collection of cell types and is therefore difficult to elucidate. Results from laboratory test tube and animal studies suggest that MSM operates at the crosstalk of inflammation and oxidative stress at the transcriptional and subcellular level 52. Due to the small size of this organosulfur compound, distinguishing between direct and indirect effects is problematic.

Anti-Inflammation

In laboratory test tube studies indicate that MSM inhibits transcriptional activity of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) by impeding the translocation into the nucleus while also preventing the degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor 58. MSM has been shown to alter post-translational modifications including blocking the phosphorylation of the p65 subunit at Serine-536, though it is unclear whether this is a direct or indirect effect. Modifications to subunits such as these contribute heavily to the regulation of the transcriptional activity of NF-κB 59, and thus more details are required to further understand this anti-inflammatory mechanism. Traditionally, the NF-κB pathway is thought of as a pro-inflammatory signaling pathway responsible for the upregulation of genes encoding cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules . The inhibitory effect of MSM on NF-κB results in the downregulation of mRNA for interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in vitro 60. As expected, translational expression of these cytokines is also reduced; furthermore, IL-1 and TNF-α are inhibited in a dose-dependent manner 61.

MSM can also diminish the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) through suppression of NF-κB; thus lessening the production of vasodilating agents such as nitric oxide (NO) and prostanoids 58. NO not only modulates vascular tone 62 but also regulates mast cell activation [93]; therefore, MSM may indirectly have an inhibitory role on mast cell mediation of inflammation. With the reduction in cytokines and vasodilating agents, flux and recruitment of immune cells to sites of local inflammation are inhibited.

At the subcellular level, the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome senses cellular stress signals and responds by aiding in the maturation of inflammatory markers. MSM negatively affects the expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome by downregulating the NF-κB production of the NLRP3 inflammasome transcript and/or by blocking the activation signal in the form of mitochondrial generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) 61.

MSM dietary supplement

As a therapeutic agent, MSM utilizes its unique penetrability properties to alter physiological effects at the cellular and tissue levels. Furthermore, MSM has the ability to act as a carrier or co-transporter for other therapeutic agents, even furthering its potential applications.

In addition to arthritis, MSM improves inflammation in a number of other conditions. For example, MSM attenuated cytokine expression in animal study for induced colitis 63, lung injury 64 and liver injury 65. Hasegawa and colleagues 66 reported that MSM was useful in protecting against UV-induced inflammation when applied topically and acute allergic inflammation after pre-treatment with a 2.5% aqueous drinking solution.

MSM is effective at reducing other inflammatory pathologies in humans as well. In a physician’s review of clinical case studies, MSM was an effective treatment for four out of six patients suffering from interstitial cystitis 67. Additionally, MSM is also suggested to alleviate the symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis 68. Though the reduction in systemic exercise-induced inflammation by MSM has been observed 69, human studies have not explored the inflammatory effects directly at the cartilage or synovium, as seen in the reduced synovitis inflammation in mice given MSM 70.

MSM joint supplement

Arthritis and Inflammation

Arthritis is an inflammatory condition of the joints that currently affects approximately 58 million adults, with an estimated increase to 78.4 million by 2040 71. This inflammation is characterized by pain, stiffness, and a reduced range of motion with regards to the arthritic joint(s). MSM is currently a alternative medicine treatment alone and in combination for arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. MSM, as a micronutrient with enhanced penetrability properties, is commonly integrated with other anti-arthritic agents including glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and boswellic acid.

As mentioned previously, a number of in vitro studies suggest that MSM exerts an anti-inflammatory effect through the reduction in cytokine expression. Similar results have been observed with MSM in experimentally induced-arthritic animal models, as evidenced by cytokine reductions in mice 66 and rabbits 72. Additionally, MSM in a combinatorial supplement with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate effectively reduced C-reactive protein (CRP) in rats with experimentally-induced acute and chronic rheumatoid arthritis 73.

To date, most arthritic human studies have been non-invasive and assess joint condition through the use of subject questionnaires such as the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF36), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain, and the Lequesne Index. In his overview of MSM, Dr. Stanley Jacob references eleven case studies of patients suffering from osteoarthritis who experienced improved symptoms following supplementation with MSM 74. Clinical trials suggest MSM is effective in reducing pain, as indicated by the VAS pain scale, WOMAC pain subscale, SF36 pain subscale and Lequesne Index. Concurrent improvements were also noted in stiffness and swelling. Furthermore, in the study conducted by Usha and Naidu 75, MSM in combination with glucosamine potentiated the improvements in pain, pain intensity, and swelling.

Other human studies utilizing combination therapies report similar results. For instance, arthritis associated pain and stiffness was significantly improved through the use of Glucosamine, Chondroitin sulfate, and MSM (GCM) 76. Only marginal improvements in pain and stiffness were observed when a Glucosamine, Chondroitin sulfate, and MSM (GCM) combination was supplemented on top of modifications to diet and exercise in sedentary obese women diagnosed with osteoarthritis 77. MSM was also shown to be effective in reducing arthritis pain when used in combination with boswellic acid 78 and type II collagen 79.

Cartilage Preservation

Cartilage degradation has long been thought of as the driving force of osteoarthritis 80. Articular cartilage is characterized by a dense extracellular matrix with little to no blood supply driving nutrient extraction from the adjacent synovial fluid 81. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-1β and TNF-α, are implicated in the destructive process of cartilage extracellular matrix 82. With minimal blood supply and possible hypoxic microenvironments, in vitro studies suggest that MSM protects cartilage through its suppressive effects on IL-1β and TNF-α 60 and its possibly normalizing hypoxia-driven alterations to cellular metabolism 83.

Disruption of this destructive autocrine or paracrine signaling by MSM has also been observed in surgically-induced osteoarthritis rabbits by the reduction in cartilage and synovial tissue 72, TNF-α, and the protected articular cartilage surface during OA progression. Histopathology of a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) rat model supplemented with a GCM combination demonstrated decreased synovium proliferation and the development of an irregular edge at the articular joint 84. Furthermore, MSM supplementation in osteoarthritis mice significantly decreased cartilage surface degeneration 85. In fact the protective effects of MSM can be seen as far back as 1991, when Murav’ev and colleagues described the decreased knee joint degeneration of arthritic mice 86. Interestingly, endogenous serum MSM becomes elevated in sheep post-meniscal destabilization caused osteoarthritis 87; however, the magnitude of this physiological response was not large enough to protect against cartilage erosion.

Improve Range of Motion and Physical Function

In studies with osteoarthritic populations given MSM daily, significant improvements in physical function were observed, as assessed through the WOMAC, SF36 and Aggregated Locomotor Function 88. Objective kinetic knee measurements following eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage were not conclusive but suggest that MSM may aid in maximal isometric knee extensor recovery 89.

MSM has been used in a number of combination therapies with positive results. Supplementation with glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, MSM, guava leaf extract, and Vitamin D improved physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis based on the Japanese Knee OA Measure 90. A GCM supplement was successful in increasing functional ability and joint mobility 76. MSM in combination with boswellic acid was also shown to improve knee joint function as assessed through the Lequesne Index 91. MSM with arginine l-α-ketoglutarate, hydrolyzed Type I collagen, and bromelain taken for three months daily post-rotator cuff repair improved repair integrity without affecting objective functional outcomes 92.

Other studies exploring the uses of MSM in combination therapies failed to show significant improvements. In humans, MSM and boswellic acid reduced the need for anti-inflammatory drugs but was not more effective than the placebo as a treatment for gonarthrosis 93. However, when a GCM combination supplement was administered in addition to dietary and exercise interventions, no significant improvements were noted when compared to the non-supplemented group 94.

Subjects with lower back pain undergoing conventional physical therapy with supplementation of a glucosamine complex containing MSM reported an improvement in their quality of life 95. A 2011 systematic review of GCM supplements as a treatment for spinal degenerative joint disease and degenerative disc disease failed to come to a conclusion on efficacy due to the scarcity of quality literature 96.

To Reduce Muscle Soreness Associated with Exercise

Prolonged strenuous exercise can result in muscle soreness caused by microtrauma to muscles and surrounding connective tissue leading to a local inflammatory response 97. MSM is alluded to be an effective agent against muscle soreness because of its anti-inflammatory effects as well as its possible sulfur contribution to connective tissue. Endurance exercise-induced muscle damage was reduced with MSM supplementation, as measured by creatine kinase 98. Pre-treatment with MSM reduced muscle soreness following strenuous resistance exercises 99 and endurance exercise 100.

MSM supplement side effects

MSM appears to be well-tolerated and safe. Only minor side effects are associated with MSM in humans including allergy, upset stomach, and skin rashes 57.

A number of toxicity studies have been conducted in an array of animals including rats 101, mice 102 and dogs 103. In a preliminary toxicity study report, a single mortality was reported in a female rat given an oral aqueous dose of 15.4 g/kg after two days; however, a post-mortem necropsy examination showed no gross pathological alterations. Other technical reports indicate that mild skin and eye irritation have been observed when MSM is applied topically. Nonetheless, under the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) GRAS notification, MSM is considered safe at dosages under 4845.6 mg/day 104.

MSM and Alcohol

Much anecdotal evidence from web forums and videos exists regarding chronic MSM use and increased sensitivity to alcohol. Since other sulfur containing molecules, such as disulfiram, are used to combat alcoholism by causing adverse reactions when consuming alcohol 105, it is worth mentioning there have been no studies to date examining the effects of MSM usage on alcohol metabolism or addiction pathways. As mentioned previously, MSM readily crosses the blood brain barrier and becomes evenly distributed throughout the brain 106; however, studies have not focused on the metabolic effects on the different neural pathways. Further studies are needed to assess the safety of MSM use with recreational alcohol use.

- Hendler SS, Rorvik D (editors). PDR for Nutritional Supplements. 1st Edition. Montvale: Thomson Healthcare, 2001:93-96.[↩]

- Sawitzke AD, Shi H, Finco MF, et al. The Effect of Glucosamine and/or Chondroitin Sulfate on the Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Report from the Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2008; 58(10):3183–3191.[↩]

- Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, Maxwell LJ. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD005614. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005614.pub2. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005614.pub2/full[↩]

- Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. Costs of osteoarthritis: estimates from a geographically defined population. Journal of Rheumatology 1995;22(Suppl 43):23-5.[↩]

- Felson DT. The epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 1990;20(3(Suppl 1[↩]

- Felson DT. Epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Epidemiologic Reviews 1988;10:1-28.[↩]

- Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1990;33(11):1601-10.[↩]

- Solomon L. Clinical features of osteoarthritis. In: Ruddy S, Harris ED, Sledge CB editor(s). Kelly’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 6th Edition. Vol. 2, Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company, 2001:1409-18.[↩][↩]

- Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005522. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005522.pub2. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005522.pub2/full[↩]

- Bellamy N, Campbell J, Welch V, Gee TL, Bourne R, Wells GA. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005321.pub2/full[↩]

- Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD004376. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3/full[↩]

- Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD005118. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005118.pub2. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005118.pub2/full[↩]

- Newberry SJ, FitzGerald J, SooHoo NF, et al. Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee: An Update Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017 May. (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 190.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK447543[↩]

- Deal CL, Moskowitz RW. Nutraceuticals as therapeutic agents in osteoarthritis. The role of glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate and collagen hydrolysate. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 1999;25:379-95.[↩]

- Fajardo M, Di Cesare PE. Disease-modifying therapies for osteoarthritis. Drugs Aging 2005;22(2):141-61.[↩]

- Altman RD, Hochberg M, Moskowitz RW, Schnitzer J. on behalf of the American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis on the hip and the knee. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2000;43:1905-15.[↩]

- Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, Cucherat M, Henrotin Y, Reginster JY. Structural and symptomatic efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin in knee osteoarthritis: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003;163(13):1514-22.[↩]

- Johnson KA, Hulse DA, Hart RC, Kochevar D, Chu Q. Effects of an orally administered mixture of chondroitin sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride and manganese ascorbate on synovial fluid chondroitin sulfate 3B3 and 7D4 epitope in a canine cruciate ligament transection model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2001;9(1):14-21.[↩]

- Cordoba F, Nimni ME. Chondroitin sulfate and other sulfate containing chondroprotective agents may exhibit their effects by overcoming a deficiency of sulfur amino acids. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2003;11(3):228-30.[↩]

- Questions and Answers: NIH Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial Primary Study. https://nccih.nih.gov/research/results/gait/qa.htm[↩]

- Herbal Remedies, Supplements & Acupuncture for Arthritis. https://www.rheumatology.org/i-am-a/patient-caregiver/treatments/herbal-remedies-supplements-acupuncture-for-arthritis[↩]

- Leeb BF, Schweitzer H, Montag K, Smolen JS. A metaanalysis of chondroitin sulfate in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol . 2000;27(1):205-211.[↩]

- Tallia AF, Cardone DA. Asthma exacerbation associated with glucosamine-chondroitin supplement. J Am Board Fam Pract . 2002;15(6):481-484.[↩][↩]

- Huang J, Olivenstein R, Taha R, Hamid Q, Ludwig M. Enhanced proteoglycan deposition in the airway wall of atopic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 1999;160(2):725-729.[↩]

- Ricciardelli C, Quinn DI, Raymond WA, et al. Elevated levels of peritumoral chondroitin sulfate are predictive of poor prognosis in patients treated by radical prostatectomy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer Res . 1999;59(10):2324-2328.[↩]

- Ameye LG, Chee WS. Osteoarthritis and nutrition. From nutraceuticals to functional foods: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2006;8(4):R127. doi:10.1186/ar2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1779427/[↩]

- Brien S, Prescott P, Lewith G. Meta-Analysis of the Related Nutritional Supplements Dimethyl Sulfoxide and Methylsulfonylmethane in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine : eCAM. 2011;2011:528403. doi:10.1093/ecam/nep045. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3135791/[↩][↩]

- Why are dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl sulfone such good solvents? Clark T, Murray JS, Lane P, Politzer P. J Mol Model. 2008 Aug; 14(8):689-97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18458968/[↩]

- Bennet R.C., Corder W.C., Finn R.K. Miscellaneous seperation processes. In: Perry R.H., Chilton C.H., editors. Chemical Engineers’ Handbook. Volume 5 McGraw-Hill Book Company; New York, NY, USA: 1973.[↩]

- Firn R. Nature’s Chemicals: The Natural Products That Shaped Our World. Oxford University Press on Demand; Oxford, UK: 2010. Chapter 4: Are natural products different from synthetic chemicals?[↩]

- Metabolic fingerprint of dimethyl sulfone (DMSO2) in microbial-mammalian co-metabolism. He X, Slupsky CM. J Proteome Res. 2014 Dec 5; 13(12):5281-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25245235/[↩]

- Low-dose aspartame consumption differentially affects gut microbiota-host metabolic interactions in the diet-induced obese rat. Palmnäs MS, Cowan TE, Bomhof MR, Su J, Reimer RA, Vogel HJ, Hittel DS, Shearer J. PLoS One. 2014; 9(10):e109841. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4197030/[↩]

- Effects of high dietary fibre diets formulated from by-products from vegetable and agricultural industries on plasma metabolites in gestating sows. Yde CC, Bertram HC, Theil PK, Knudsen KE. Arch Anim Nutr. 2011 Dec; 65(6):460-76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22256676/[↩]

- Following healthy pregnancy by NMR metabolomics of plasma and correlation to urine. Pinto J, Barros AS, Domingues MR, Goodfellow BJ, Galhano E, Pita C, Almeida Mdo C, Carreira IM, Gil AM. J Proteome Res. 2015 Feb 6; 14(2):1263-74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25529102/[↩]

- Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases. Sangha O. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Dec; 39 Suppl 2:3-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11276800/[↩]

- EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, Bannwarth B, Bijlsma JW, Dieppe P, Gunther K, Hauselmann H, Herrero-Beaumont G, Kaklamanis P, Lohmander S, Leeb B, Lequesne M, Mazieres B, Martin-Mola E, Pavelka K, Pendleton A, Punzi L, Serni U, Swoboda B, Verbruggen G, Zimmerman-Gorska I, Dougados M, Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials ESCISIT. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 Dec; 62(12):1145-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1754382/[↩]

- Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 2: treatment approaches. Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Hochberg MC, McAlindon T, Dieppe PA, Minor MA, Blair SN, Berman BM, Fries JF, Weinberger M, Lorig KR, Jacobs JJ, Goldberg V. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Nov 7; 133(9):726-37. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11074906/[↩]

- Nutraceuticals as therapeutic agents in osteoarthritis. The role of glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and collagen hydrolysate. Deal CL, Moskowitz RW. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999 May; 25(2):379-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10356424/[↩]

- “Crystalline DMSO”: DMSO2. Bertken R. Arthritis Rheum. 1983 May; 26(5):693-4. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.1780260525/pdf[↩]

- Absorption, distribution and elimination of labeled dimethyl sulfoxide in man and animals. Kolb KH, Jaenicke G, Kramer M, Schulze PE. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1967 Mar 15; 141(1):85-95. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1967.tb34869.x/epdf[↩]

- Osteoarthritis and nutrition. From nutraceuticals to functional foods: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Ameye LG, Chee WS. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006; 8(4):R127. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1779427/[↩]

- Topical agents in the treatment of rheumatic disorders. Rosenstein ED. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999 Nov; 25(4):899-918, viii. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10573765/[↩]

- Usha PR, Naidu MUR. Randomised, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled study of oral glucosamine, methylsulfonylmethane and their combination in osteoarthritis. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2004;24:353–363. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424060-00005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17516722[↩]

- Kim LS, Axelrod LJ, Howard P, Buratovich N, Waters RF. Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: a pilot clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.10.003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16309928[↩]

- Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) blocks conduction in peripheral nerve C fibers: a possible mechanism of analgesia. Evans MS, Reid KH, Sharp JB Jr. Neurosci Lett. 1993 Feb 19; 150(2):145-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8469412/[↩]

- Effects of dimethyl sulfoxide on the oxidative function of human neutrophils. Beilke MA, Collins-Lech C, Sohnle PG. J Lab Clin Med. 1987 Jul; 110(1):91-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3598341/[↩]

- FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee meeting: methotrexate; guidelines for the clinical evaluation of antiinflammatory drugs; DMSO in scleroderma. Paulus HE. Arthritis Rheum. 1986 Oct; 29(10):1289-90. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.1780291017/pdf[↩]

- [Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl sulfone on a destructive process in the joints of mice with spontaneous arthritis]. Murav’ev IuV, Venikova MS, Pleskovskaia GN, Riazantseva TA, Sigidin IaA. Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter. 1991 Mar-Apr; (2):37-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1881708/[↩]

- Hasegawa T, Ueno S, Kumamoto S, Yoshikai Y. Suppressive effect of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) on type II collagen-induced arthritis in DBA/1J mice. Japanese Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2004;32(7):421–427.[↩]

- Sulfur in human nutrition and applications in medicine. Parcell S. Altern Med Rev. 2002 Feb; 7(1):22-44. http://www.altmedrev.com/publications/7/1/22.pdf[↩]

- MSM GRAS Notice. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/GRAS/NoticeInventory/ucm269126.pdf[↩]

- Butawan M, Benjamin RL, Bloomer RJ. Methylsulfonylmethane: Applications and Safety of a Novel Dietary Supplement. Nutrients. 2017;9(3):290. doi:10.3390/nu9030290. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5372953/[↩][↩]

- Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: a pilot clinical trial. Kim LS, Axelrod LJ, Howard P, Buratovich N, Waters RF. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006 Mar; 14(3):286-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16309928/[↩]

- Jacobs S, Lawrence RM, Siegel M. Miracle MSM: The Natural Solution for Pain. New York, NY, USA: GP Putnam; 1999.[↩]

- Toxicity of methylsulfonylmethane in rats. Horváth K, Noker PE, Somfai-Relle S, Glávits R, Financsek I, Schauss AG. Food Chem Toxicol. 2002 Oct; 40(10):1459-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12387309/[↩]

- Oral developmental toxicity study of methylsulfonylmethane in rats. Magnuson BA, Appleton J, Ryan B, Matulka RA. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007 Jun; 45(6):977-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17258373/[↩]

- MSM Guide. http://msmguide.com/safety-and-metabolism-research/[↩][↩]

- The anti-inflammatory effects of methylsulfonylmethane on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in murine macrophages. Kim YH, Kim DH, Lim H, Baek DY, Shin HK, Kim JK. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009 Apr; 32(4):651-6. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bpb/32/4/32_4_651/_article[↩][↩]

- The Regulation of NF-κB Subunits by Phosphorylation. Christian F, Smith EL, Carmody RJ. Cells. 2016 Mar 18; 5(1): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4810097/[↩]

- Oshima Y., Amiel D., Theodosakis J. The effect of distilled methylsulfonylmethane (msm) on human chondrocytes in vitro. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2007;15:C123. doi: 10.1016/S1063-4584(07)61846-9.[↩][↩]

- Methylsulfonylmethane inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Ahn H, Kim J, Lee MJ, Kim YJ, Cho YW, Lee GS. Cytokine. 2015 Feb; 71(2):223-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25461402/[↩][↩]

- The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Tousoulis D, Kampoli AM, Tentolouris C, Papageorgiou N, Stefanadis C. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012 Jan; 10(1):4-18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22112350/[↩]

- The effect of methylsulfonylmethane on the experimental colitis in the rat. Amirshahrokhi K, Bohlooli S, Chinifroush MM. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011 Jun 15; 253(3):197-202. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21463646/[↩]

- Effect of methylsulfonylmethane on paraquat-induced acute lung and liver injury in mice. Amirshahrokhi K, Bohlooli S. Inflammation. 2013 Oct; 36(5):1111-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23595869/[↩]

- Hepatoprotective effect of methylsulfonylmethane against carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury in rats. Kamel R, El Morsy EM. Arch Pharm Res. 2013 Sep; 36(9):1140-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23591777/[↩]

- Hasegawa T., Ueno S., Kumamoto S., Yoshikai Y. Suppressive effect of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) on type ii collagen-induced arthritis in dba/1j mice. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;32:421–428.[↩][↩]

- Dimethyl sulfone (DMSO2) in the treatment of interstitial cystitis. Childs SJ. Urol Clin North Am. 1994 Feb; 21(1):85-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8284850/[↩]

- Methylsulfonylmethane as a treatment for seasonal allergic rhinitis: additional data on pollen counts and symptom questionnaire. Barrager E, Schauss AG. J Altern Complement Med. 2003 Feb; 9(1):15-6. http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/107555303321222874[↩]

- The Influence of Methylsulfonylmethane on Inflammation-Associated Cytokine Release before and following Strenuous Exercise. van der Merwe M, Bloomer RJ. J Sports Med (Hindawi Publ Corp). 2016; 2016():7498359. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5097813/[↩]

- Moore R., Morton J. Diminished inflammatory joint disease in mrl/1pr mice ingesting dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) Fed. Proc. 1985;44:530.[↩]

- Updated Projected Prevalence of Self-Reported Doctor-Diagnosed Arthritis and Arthritis-Attributable Activity Limitation Among US Adults, 2015-2040. Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, Theis KA, Boring MA. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Jul; 68(7):1582-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27015600/[↩]

- Amiel D., Healey R.M., Oshima Y. Assessment of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) on the development of osteoarthritis (OA): An animal study. FASEB J. 2008;22:1094.3.[↩][↩]

- The effectiveness of Echinacea extract or composite glucosamine, chondroitin and methyl sulfonyl methane supplements on acute and chronic rheumatoid arthritis rat model. Arafa NM, Hamuda HM, Melek ST, Darwish SK. Toxicol Ind Health. 2013 Mar; 29(2):187-201. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22173958/[↩]

- Jacob S.W., Appleton J. Msm-the Definitive Guide: A Comprehensive Review of the Science and Therapeutics of Methylsulfonylmethane. Freedom Press; Topanga, CA, USA: 2003.[↩]

- Randomised, Double-Blind, Parallel, Placebo-Controlled Study of Oral Glucosamine, Methylsulfonylmethane and their Combination in Osteoarthritis. Usha PR, Naidu MU. Clin Drug Investig. 2004; 24(6):353-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17516722/[↩]

- Vidyasagar S., Mukhyaprana P., Shashikiran U., Sachidananda A., Rao S., Bairy K.L., Adiga S., Jayaprakash B. Efficacy and tolerability of glucosamine chondroitin sulphate-methyl sulfonyl methane (MSM) in osteoarthritis of knee in indian patients. Iran. J. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;3:61–65.[↩][↩]

- Effects of diet type and supplementation of glucosamine, chondroitin, and MSM on body composition, functional status, and markers of health in women with knee osteoarthritis initiating a resistance-based exercise and weight loss program. Magrans-Courtney T, Wilborn C, Rasmussen C, Ferreira M, Greenwood L, Campbell B, Kerksick CM, Nassar E, Li R, Iosia M, Cooke M, Dugan K, Willoughby D, Soliah L, Kreider RB. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2011 Jun 20; 8(1):8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141631/[↩]

- Methylsulfonylmethane and boswellic acids versus glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee arthritis: Randomized trial. Notarnicola A, Maccagnano G, Moretti L, Pesce V, Tafuri S, Fiore A, Moretti B. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016 Mar; 29(1):140-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26684635/[↩]

- Effects of AR7 Joint Complex on arthralgia for patients with osteoarthritis: results of a three-month study in Shanghai, China. Xie Q, Shi R, Xu G, Cheng L, Shao L, Rao J. Nutr J. 2008 Oct 27; 7():31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2588628/[↩]

- Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!) Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013;21:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23194896[↩]

- Sophia Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The Basic Science of Articular Cartilage: Structure, Composition, and Function. Sports Health. 2009;1(6):461-468. doi:10.1177/1941738109350438. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3445147/[↩]

- Kobayashi M., Squires G.R., Mousa A., Tanzer M., Zukor D.J., Antoniou J., Feige U., Poole A.R. Role of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor α in matrix degradation of human osteoarthritic cartilage. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2005;52:128–135. doi: 10.1002/art.20776. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15641080[↩]

- Caron JM, Caron JM. Methyl Sulfone Blocked Multiple Hypoxia- and Non-Hypoxia-Induced Metastatic Targets in Breast Cancer Cells and Melanoma Cells. Slominski AT, ed. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0141565. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141565. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4633041/[↩]

- Arafa N.M., Hamuda H.M., Melek S.T., Darwish S.K. The effectiveness of echinacea extract or composite glucosamine, chondroitin and methyl sulfonyl methane supplements on acute and chronic rheumatoid arthritis rat model. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2013;29:187–201. doi: 10.1177/0748233711428643. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22173958[↩]

- Ezaki J., Hashimoto M., Hosokawa Y., Ishimi Y. Assessment of safety and efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane on bone and knee joints in osteoarthritis animal model. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2013;31:16–25. doi: 10.1007/s00774-012-0378-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23011466[↩]

- Murav’ev I., Venikova M., Pleskovskaia G., Riazantseva T., Sigidin I. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl sulfone on a destructive process in the joints of mice with spontaneous arthritis. Patol. Fiziol. Eksp. Ter. 1990;2:37–39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1881708[↩]

- Maher A.D., Coles C., White J., Bateman J.F., Fuller E.S., Burkhardt D., Little C.B., Cake M., Read R., McDonagh M.B. 1H nmr spectroscopy of serum reveals unique metabolic fingerprints associated with subtypes of surgically induced osteoarthritis in sheep. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:4261–4268. doi: 10.1021/pr300368h. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22784358[↩]

- Debi R., Fichman G., Ziv Y.B., Kardosh R., Debbi E., Halperin N., Agar G. The role of msm in knee osteoarthritis: A double blind, randomized, prospective study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2007;15:C231. doi: 10.1016/S1063-4584(07)62057-3.[↩]

- Melcher D.A., Lee S.-R., Peel S.A., Paquette M.R., Bloomer R.J. Effects of methylsulfonylmethane supplementation on oxidative stress, muscle soreness, and performance variables following eccentric exercise. Gazz. Med. Ital.-Arch. Sci. Med. 2016;175:1–13.[↩]

- NAKASONE Y, WATABE K, WATANABE K, et al. Effect of a glucosamine-based combination supplement containing chondroitin sulfate and antioxidant micronutrients in subjects with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2011;2(5):893-899. doi:10.3892/etm.2011.298. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3440771/[↩]

- Notarnicola A., Maccagnano G., Moretti L., Pesce V., Tafuri S., Fiore A., Moretti B. Methylsulfonylmethane and boswellic acids versus glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee arthritis: Randomized trial. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2016;29:140–146. doi: 10.1177/0394632015622215. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26684635[↩]

- Gumina S., Passaretti D., Gurzi M., Candela V. Arginine l-alpha-ketoglutarate, methylsulfonylmethane, hydrolyzed type i collagen and bromelain in rotator cuff tear repair: A prospective randomized study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2012;28:1767–1774. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.737772. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23043451[↩]

- Notarnicola A., Tafuri S., Fusaro L., Moretti L., Pesce V., Moretti B. The “mesaca” study: Methylsulfonylmethane and boswellic acids in the treatment of gonarthrosis. Adv. Ther. 2011;28:894–906. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0068-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21986780[↩]

- Magrans-Courtney T, Wilborn C, Rasmussen C, et al. Effects of diet type and supplementation of glucosamine, chondroitin, and MSM on body composition, functional status, and markers of health in women with knee osteoarthritis initiating a resistance-based exercise and weight loss program. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2011;8:8. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-8-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141631/[↩]

- Tant L, Gillard B, Appelboom T. Open-label, randomized, controlled pilot study of the effects of a glucosamine complex on Low back pain. Current Therapeutic Research, Clinical and Experimental. 2005;66(6):511-521. doi:10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.12.009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3965983/[↩]

- Stuber K, Sajko S, Kristmanson K. Efficacy of glucosamine, chondroitin, and methylsulfonylmethane for spinal degenerative joint disease and degenerative disc disease: a systematic review. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2011;55(1):47-55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3044807/[↩]

- Lewis P.B., Ruby D., Bush-Joseph C.A. Muscle soreness and delayed-onset muscle soreness. Clin. Sports. Med. 2012;31:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2011.09.009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22341015[↩]

- Barmaki S., Bohlooli S., Khoshkhahesh F., Nakhostin-Roohi B. Effect of methylsulfonylmethane supplementation on exercise—Induced muscle damage and total antioxidant capacity. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2012;52:170. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22525653[↩]

- Kalman DS, Feldman S, Scheinberg AR, Krieger DR, Bloomer RJ. Influence of methylsulfonylmethane on markers of exercise recovery and performance in healthy men: a pilot study. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2012;9:46. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-9-46. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3507661/[↩]

- Withee E.D., Tippens K.M., Dehen R., Hanes D. Effects of msm on exercise-induced muscle and joint pain: A pilot study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015;12:P8. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-12-S1-P8.[↩]

- Effects of oral dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl sulfone on murine autoimmune lymphoproliferative disease. Morton JI, Siegel BV. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986 Nov; 183(2):227-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3489943/[↩]

- Takiyama K., Konishi F., Nakashima Y., Kumamoto S., Maruyama I. Single and 13-week repeated oral dose toxicity study of methylsulfonylmethane in mice. Oyo Yakuri. 2010;79:23–30.[↩]

- Accidental overdosage of joint supplements in dogs. Khan SA, McLean MK, Gwaltney-Brant S. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2010 Mar 1; 236(5):509-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20344826/[↩]

- Borzelleca J.F., Sipes I.G., Wallace K.B. Dossier in Support of the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Status of Optimsm (Methylsulfonylmethane; MSM) as a Food Ingredient. Food and Drug Administration; Vero Beach, FL, USA: 2007.[↩]

- mechanisms of disulfiram-induced cocaine abstinence: antabuse and cocaine relapse. Gaval-Cruz M, Weinshenker D. Mol Interv. 2009 Aug; 9(4):175-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2861803/[↩]

- Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) ingestion causes a significant resonance in proton magnetic resonance spectra of brain and cerebrospinal fluid. Willemsen MA, Engelke UF, van der Graaf M, Wevers RA. Neuropediatrics. 2006 Oct; 37(5):312-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17236113/[↩]