Green tea

Green tea is made from the leaves of the plant Camellia sinensis of the Theaceae family 1. Moreover, green, black, white and oolong teas all come from the same plant, Camellia sinensis, but are prepared using different methods. Green tea is made by processing fresh Camellia sinensis leaves using heat or hot steam immediately after collection, thus minimising any oxidation processes. White tea is produced with minimal fermentation from new buds and young Camellia sinensis leaves, which are harvested only once a year in early spring 2. In black tea the leaves undergo several treatments, including withering by blowing air, preconditioning, ‘cut‐tear‐curl’, fermentation and final drying, which result in an oxidised tea 3. Oolong tea is made from wilted, bruised, and partially oxidized Camellia sinensis leaves, creating an intermediate kind of tea. Shortly after harvesting, tea leaves begin to wilt and oxidize. During oxidation, chemicals in the leaves are broken down by enzymes, resulting in darkening of the leaves and the well-recognized aroma of tea. This oxidation process can be stopped by heating, which inactivates the enzymes. The amount of oxidation and other aspects of processing determine a tea’s type. Black tea is produced when tea leaves are wilted, bruised, rolled, and fully oxidized. In contrast, green tea is made from unwilted leaves that are not oxidized. Oolong tea is made from wilted, bruised, and partially oxidized leaves, creating an intermediate kind of tea. White tea is made from young leaves or growth buds that have undergone minimal oxidation. Dry heat or steam can be used to stop the oxidation process, and then the leaves are dried to prepare them for sale.

Tea (Camellia sinensis) is the most highly consumed manufactured drink in the world, second only to water 4, 5. Approximately 20% of the world’s Camellia sinensis consumption is in the form of green tea; with black tea accounting for about 75 percent of the world’s tea consumption 6, 7. In the United States, United Kingdom and Europe, black tea is the most common tea beverage consumed; green tea is the most popular tea in Japan and China 8. Oolong and white tea are consumed in much lesser amounts around the world 8.

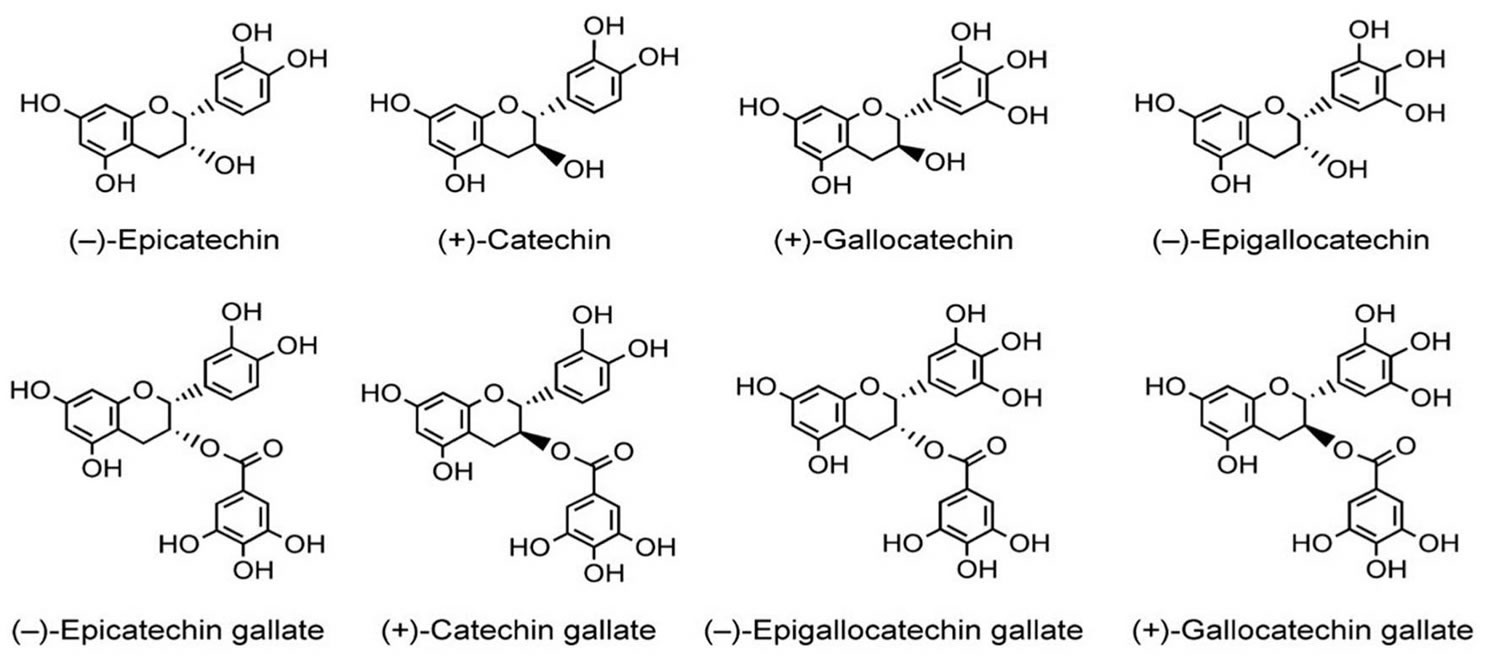

The active ingredients of green tea are composed of polyphenols, alkaloids (caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine), amino acids, carbohydrates, proteins, chlorophyll, volatile organic compounds (chemicals that readily produce vapors and contribute to the odor of tea), fluoride, aluminum, minerals, and trace elements 9, 10, 11. The polyphenols, most of which are flavonols, commonly known as catechins 12, are thought to be responsible for the health benefits that have traditionally been attributed to tea, especially green tea. Catechins are a part of the chemical family of flavonoids, a naturally occurring antioxidant, and a secondary metabolite in certain plants. Green tea contains higher amounts of catechins than black tea 13 and green tea processing prevents oxidation 14. After fermentation from green to black tea, about 15% of catechins remain unchanged while the rest of the catechins are converted to theaflavins, which are polyphenol pigments and thearubigins 15. Brewing conditions, including water temperature and infusion time, influence the antioxidant capacity of green tea 16. The active catechins and their respective concentrations in green tea infusions are listed in the Table 1 below.

Although iced and ready-to-drink teas are becoming popular worldwide, they may not have the same polyphenol content as an equal volume of brewed tea 17. The polyphenol concentration of any particular tea beverage depends on the type of tea, the amount used, the brew time, and the temperature 9. The highest polyphenol concentration is found in brewed hot tea, less in instant preparations, and lower amounts in iced and ready-to-drink teas 9. As the percentage of tea solids (i.e., dried tea leaves and buds) decreases, so does the polyphenol content 18. Ready-to-drink teas frequently have lower levels of tea solids and lower polyphenol contents because their base ingredient may not be brewed tea 19. The addition of other liquids, such as juice, will further dilute the tea solids 18. Decaffeination reduces the catechin content of teas 20.

Dietary supplements containing green tea extracts are also available 7. In a U.S. study that evaluated 19 different green tea supplements for tea catechin and caffeine content, the product labels varied in their presentation of catechin and caffeine information, and some values reported on product labels were inconsistent with analyzed values 7.

Green tea catechins are well recognized for their essential anti-inflammatory, photo-protective, antioxidant, and chemo-preventive functions. The catechins found in green tea include epigallocatechin‐3‐gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin‐3‐gallate (ECG) and epicatechin (EC), gallocatechins and gallocatechin gallate. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is the most active, abundant and most studied catechin in green tea 13, as it is a powerful antioxidant believed to be an important determinant of the therapeutic qualities of green tea 21. It is suggested that EGCG works by suppressing the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) and regulating their permeability, thereby cutting off the blood supply to cancerous cells 22. Several in-vitro studies (test tube studies) and in-vivo animal and human studies demonstrated green tea catechin’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, photo-protective, and chemo-preventative effects after topical application and/or oral ingestion 23, 24, 25, 26.

Tea is brewed from dried leaves and buds (either in tea bags or loose), prepared from dry instant tea mixes, or sold as ready-to-drink iced teas. So-called herbal teas are not really teas but infusions of boiled water with dried fruits, herbs, and/or flowers.

- Green, black, white and oolong teas all come from the same plant, Camellia sinensis, but are prepared using different methods. To produce green tea, fresh leaves from the plant are lightly steamed and crushed.

- Tea has been used for medicinal purposes in China and Japan for thousands of years.

- Current uses of green tea as a beverage or dietary supplement include improving mental alertness, relieving digestive symptoms and headaches, and promoting weight loss.

- Green tea and its extracts, such as one of its components, EGCG (epigallocatechin‐3‐gallate), have been studied for their possible protective effects against heart disease and cancer.

- Green tea is consumed as a beverage. It is also sold in liquid extracts, capsules, and tablets and is sometimes used in topical products (intended to be applied to the skin).

- White Tea is the least processed, and it has a light, sweet flavor. One laboratory study showed white tea sped up the breakdown of existing fat cells and blocked the formation of new ones. Whether it has the same effects in the human body remains to be seen.

- Black Tea is the type of tea that’s often served in Chinese restaurants and used to make iced tea. Black tea is produced when tea leaves are wilted, bruised, rolled, and fully oxidized– a process that allows it to change chemically and often increases its caffeine content. The tea has a strong, rich flavor. Whether it helps with weight loss isn’t certain. But research done on rats suggests substances called polyphenols in black tea might help block fat from being absorbed in the intestines.

- Oolong Tea is made by drying tea leaves in the hot sun. Like green tea, it’s a rich source of catechins. In one study, more than two-thirds of overweight people who drank oolong tea every day for six weeks lost more than 2 pounds and trimmed belly fat.

- Except for decaffeinated green tea products, green tea and green tea extracts contain substantial amounts of caffeine. The average cup of green tea, however, contains from 10-50 mg of caffeine and over-consumption may cause irritability, insomnia, nervousness, and tachycardia (fast heart rate).

- All teas naturally have high amounts of health-promoting substances called flavonoids. So they’re thought to bring down inflammation and protect against conditions like heart disease and diabetes.

- Teas have a type of flavonoid called catechins (epigallocatechin gallate) that may boost metabolism and help your body break down fats more quickly.

Figure 1. Green tea leaves

Figure 2. Matcha powder

Figure 3. Green tea catechins chemical structure

[Source 27 ]What are antioxidants?

Antioxidants are substances that are found in food and in vitamin and mineral supplements, that can neutralize free radicals in your body and stop them damaging your health. But while they’re generally healthy for you, antioxidants can cause problems, too.

Antioxidants became prominent 20 years ago, because research suggested they would be able to prevent heart disease and many other chronic conditions. This research led many people to start taking antioxidant supplements.

The best known antioxidants are vitamins A, C and E, beta-carotene, lutein, lycopene and selenium. Your body also produces its own antioxidants.

What are free radicals?

Inside the cells in your body, many chemical reactions take place. Sometimes, by-products known as free radicals form. Free radicals have a bad reputation, but they’re not all bad. Some are used by your body’s immune system to attack viruses or bacteria. But some free radicals can damage cells. Others might contribute to health problems such as heart disease, some cancers and degeneration of the macula in the eye.

What are the ingredients of tea?

Tea is composed of polyphenols, alkaloids (caffeine, theophylline, and theobromine), amino acids, carbohydrates, proteins, chlorophyll, volatile organic compounds (chemicals that readily produce vapors and contribute to the odor of tea), fluoride, aluminum, minerals, and trace elements. The polyphenols, a large group of plant chemicals that includes the catechins, are thought to be responsible for the health benefits that have traditionally been attributed to tea, especially green tea. The most active and abundant catechin in green tea is epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG). The active catechins and their respective concentrations in green tea infusions are listed in the table below. These chemical compounds act as antioxidants, which fight against free radicals in the body. Free radicals can alter DNA by stealing its electrons, and this mutated DNA can increase LDL “bad” cholesterol or alter cell membrane traffic – both harmful to our health. Though green tea is often considered higher in polyphenols than black or oolong (red) teas, studies show that – with the exception of decaffeinated tea – all teas have about the same levels of these chemicals, albeit in different proportions.

While the antioxidant action of tea is promising, some research suggests that the protein and possibly the fat in milk may reduce the antioxidant capacity of tea 28. Flavonoids, the antioxidant component in tea, are known to bind to proteins and “de-activate,” so this theory makes scientific sense 29. One study that analyzed the effects of adding skimmed, semi-skimmed, and whole milk to tea concluded that skimmed milk significantly reduced the antioxidant capacity of tea. The fattier milks also reduced the antioxidant capacity of tea, but to a lesser degree 28. Overall, it’s important to keep in mind that tea – even tea with milk – is a healthy drink. To reap the full antioxidant benefits of tea, however, it may be best to skip the milk.

Avoid purchasing expensive bottled teas or teas in coffee shops that contain added sugar or sweeteners. To enjoy the maximum benefits of drinking tea, consider brewing your own at home. You can serve it hot, or make a pitcher of home-brewed iced tea during warmer months.

Table 1. Catechin concentrations of green tea infusions

| Catechin in Green Tea Infusion | Catechin Concentration (mg/L)* | Catechin Concentration (mg/8 fl oz)* |

|---|---|---|

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | 117–442 | 25–106 |

| Epigallocatechin (EGC) | 203–471 | 49–113 |

| Epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG) | 17–150 | 4–36 |

| Epicatechin (EC) | 25–81 | 6–19 |

Abbreviations: *mg = milligram; L = liter; fl oz = fluid ounce.

[Source 30 ]Black tea contains much lower concentrations of these catechins than green tea 31. The extended oxidation of black tea increases the concentrations of thearubigins and theaflavins, two types of complex polyphenols. Oolong tea contains a mixture of simple polyphenols, such as catechins, and complex polyphenols 32. White and green tea contain similar amounts of EGCG but different amounts of other polyphenols 33.

Although iced and ready-to-drink teas are becoming popular worldwide, they may not have the same polyphenol content as an equal volume of brewed tea 34. The polyphenol concentration of any particular tea beverage depends on the type of tea, the amount used, the brew time, and the temperature 35. The highest polyphenol concentration is found in brewed hot tea, less in instant preparations, and lower amounts in iced and ready-to-drink teas 35. As the percentage of tea solids (i.e., dried tea leaves and buds) decreases, so does the polyphenol content 36. Ready-to-drink teas frequently have lower levels of tea solids and lower polyphenol contents because their base ingredient may not be brewed tea 37. The addition of other liquids, such as juice, will further dilute the tea solids 36. Decaffeination reduces the catechin content of teas 38.

Dietary supplements containing green tea extracts are also available 39. In a U.S. study that evaluated 19 different green tea supplements for tea catechin and caffeine content, the product labels varied in their presentation of catechin and caffeine information, and some values reported on product labels were inconsistent with analyzed values 39.

Green Tea and Weight Loss

Obesity (body mass index ≥ 30) and overweight (body mass index ≥ 25) are increasing due to an excessive intake of energy-dense foods and sedentary lifestyle; obesity affects more than 1.9 billion adults worldwide 40. Obesity causes about 4 million deaths globally and it is related to other prevalent pathologies including hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke, obstructive sleep apnea, and several cancers 41. Although many studies have been done on green tea and its extracts, definite conclusions cannot yet be reached on whether green tea is helpful for most of the purposes for which it is used including its use for weight loss. There are just not enough reliable data to determine whether produce a meaningful weight loss in adults who are overweight or obese 42. Green tea extracts also haven’t been shown to help people maintain a weight loss. Be wary of weight-loss claims. Some advertisements claim that tea can speed weight loss, but research on the effects of green tea and fat reduction have shown little promise of weight loss benefits. Moreover, it’s best to skip any so-called “diet” teas that may contain potentially harmful substances such as laxatives.

In a well-conducted 2012 Cochrane Review 42 the study authors looked at 15 weight loss studies and three studies measuring weight maintenance where some form of a green tea preparation was given to one group and results compared to a group receiving a control. Neither group knew whether they were receiving the green tea preparation or the control. Green tea preparations used for losing weight are extracts of green tea that contain a higher concentration of catechins and caffeine than the typical green tea beverage prepared from a tea bag and boiling water. A total of 1945 participants completed the studies, ranging in length from 12 to 13 weeks. In summary, the loss in weight in adults who had taken a green tea preparation was statistically not significant, was very small and is not likely to be clinically important. Similar results were found in studies that used other ways to measure loss in weight (body mass index, waist circumference). Studies examining the effect of green tea preparations on weight maintenance did not show any benefit compared to the use of a control preparation.

Green tea preparations appear to induce a small, statistically non-significant weight loss in overweight or obese adults 42. Because the amount of weight loss is small, it is not likely to be clinically important. Green tea had no significant effect on the maintenance of weight loss. Of those studies recording information on adverse events, only two identified an adverse event requiring hospitalisation. The remaining adverse events were judged to be mild to moderate.

Most adverse effects, such as nausea, constipation, abdominal discomfort and increased blood pressure, were judged to be mild to moderate and to be unrelated to the green tea or control intervention. No deaths were reported, although adverse events required hospitalisation. One study attempted to look at health-related quality of life by asking participants about their attitudes towards eating. Nine studies tracked participants’ compliance with green tea preparations. Studies did not include any information about the effects of green tea preparations on morbidity, costs or patient satisfaction.

In another study conducted in 2008, randomised blinded controlled trials that compared catechins (in green tea or capsules) – epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) + caffeine mixture, showed a small positive effect on weight loss and weight maintenance. However, the authors stated that further research was needed to assess whether (and to what extent) people are genetically predisposed to the effect of epigallocatechin gallate-caffeine mixtures. And due to the limitations in the review methodology mean that the overall effect size estimate was unlikely to be reliable and the conclusions should be treated with caution.

To get the same amount of EGCG used in the research, you’d need to drink about six to seven cups of your typical green tea every day. You could also try a green tea extract, but it might be risky. Though rare, high-dose tea extracts found in some weight-loss supplements have been linked to serious liver damage.

Since the 2012 Cochrane Review, more clinical studies evaluating the weight loss activity of green tea and its main secondary metabolite epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) have been done. These clinical trials were mainly randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled, except one which was single-blind and another one which was longitudinal. The duration of these clinical trials was mainly weeks (6, 8, and 12 weeks), although there is a study with 12-month intervention. There is also variability in the administered doses from 300 mg/day of EGCG to 856.8 mg/day. Analyzing the different clinical trials, it has been observed that high doses of EGCG (856.8 mg for 6–12 weeks) do have anti-obesity activity, reducing weight in women and men with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 27 kg/m² 43, 44. However, in another study in which a dose of 843 mg of EGCG was administered for 12 months, it had no effect on reductions in adiposity nor body mass index (BMI). Compared with the previous cited studies, this lack of efficacy can be attributed to the fact that this last study has only been performed with postmenopausal obese women 45. On the other hand, low doses of EGCG (300 mg/day and 560 g/day for 12 weeks) do not have any beneficial effect on weight control 46. Finally, another clinical trial elucidated that the possible mechanism of action by which EGCG exerts its anti-obesity activity is by increasing HIF1-alpha (HIF1-α) and rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR) 47.

Green Tea and Cancer Prevention

Among their many biological activities, the predominant polyphenols in green tea―Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), Epigallocatechin (EGC), Epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG) and Epicatechin (EC) and the theaflavins and thearubigins in black teas have antioxidant activity 48. These chemicals, especially Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and Epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), have substantial free radical scavenging activity and may protect cells from DNA damage caused by reactive oxygen species 48.

Tea polyphenols have also been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in laboratory and animal studies 49, 50. Research shows benefits for a variety of types of cancer, including ovarian cancer 51 and digestive system cancers 52. Green tea might also have a positive effect in reducing risk of breast, prostate, and endometrial cancers, though more evidence is needed 53. In other laboratory and animal studies, tea catechins have been shown to inhibit angiogenesis and tumor cell invasiveness 54. In addition, tea polyphenols may protect against damage caused by ultraviolet (UV) B radiation 50, 55, and they may modulate immune system function 56. Furthermore, green teas have been shown to activate detoxification enzymes, such as glutathione S-transferase and quinone reductase, that may help protect against tumor development 56. Although many of the potential beneficial effects of tea have been attributed to the strong antioxidant activity of tea polyphenols, the precise mechanism by which tea might help prevent cancer has not been established 50.

Although tea and/or tea polyphenols have been found in animal studies to inhibit tumorigenesis at different organ sites, including the skin, lung, oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, liver, pancreas, and mammary gland 57, the results of human studies—both epidemiologic and clinical studies—have been inconclusive. There is insufficient and conflicting evidence to give any firm recommendations regarding green tea consumption for cancer prevention.

The results of this 2009 Cochrane review 58, where fifty-one studies with more than 1.6 million participants, mainly of observational nature were included in this systematic review. Studies looked for an association between green tea consumption and cancer of the digestive tract, gynecological cancer including breast cancer, urological cancer including prostate cancer, lung cancer and cancer of the oral cavity. The majority of included studies were of medium to high methodological quality. The evidence that the consumption of green tea might reduce the risk of cancer was conflicting. Although many of the potential beneficial effects of tea have been attributed to the strong antioxidant activity of tea polyphenols, the precise mechanism by which tea might help prevent cancer has not been established 59. This means, that drinking green tea remains unproven in cancer prevention, but appears to be safe at moderate, regular and habitual use.

A more recent 2015 study 60 looked at the cancer-fighting effects of a compound found in green tea when combined with a drug called Herceptin, which is used in the treatment of stomach and breast cancer. Initial results in the laboratory were promising and human trials are now being planned. But this shouldn’t be taken as official advice that drinking green tea while taking Herceptin will make it more effective. This research remains at a very early stage of development. The results from the laboratory and mice studies need to be confirmed by other research groups before the team can consider testing potential treatments in humans.

Green and black tea and the prevention of cardiovascular disease

There are very few long-term studies to date examining green or black tea for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Polyphenols, the antioxidants abundant in tea, have been shown to reduce the risk of death due to cardiovascular disease 61, including stroke 62. In one study of 77,000 Japanese men and women, green tea and oolong tea consumption which was assessed by questionnaires was linked with lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease 63. Other large-scale studies show that black tea also contributes to heart health, with research suggesting that drinking at least three cups of either black or green tea per day appears to reduce the risk of stroke by 21 percent. The study also stated that drinking tea may be one of the most significant changes a person can make to reduce his or her risk of stroke 64. A randomized clinical trial would be necessary to confirm the effect. In a study of green and oolong tea consumption, regular consumption for one year reduced the risk of developing hypertension 65. Long-term regular consumption of black tea has also been shown to lower blood pressure 66. The limited evidence suggests that tea has favourable effects on cardiovascular disease risk factors, but due to the small number of trials contributing to each analysis the results should be treated with some caution and further high quality trials with longer-term follow-up are needed to confirm this 67.

Green tea for high cholesterol

Hypercholesterolemia which is high blood cholesterol values > 200 mg/dL affects over 39% of people worldwide, Europe and America being the most affected continents 68. Green tea extracts have demonstrated in in-vivo animal studies reduced total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL or “bad” cholesterol), and tryglicerides 69, 70, 71 which is mainly attributed to epigallocatechin gallate and flavonols 72, 73.. Moreover, Chungtaejeon aqueous extracts, which is a Korean fermented tea, has shown to decrease cholesterol, total serum cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol in high fat atherogenic Wistar rats 74.

A good-quality review from 2013 75 of 11 studies involving 821 people found daily consumption of green and black tea (as a drink or a capsule) could help lower cholesterol and blood pressure thanks to tea and its catechins. The authors of the review caution that most of the trials were short term and more good quality long-term trials are needed to back up their findings.

Another good-quality review from 2011 76 found drinking green tea enriched with catechins led to a small reduction in cholesterol, a main cause of heart disease and stroke. However, it’s still not clear from the evidence how much green tea you’d need to drink to see a positive effect on your health, or what the long-term effects of drinking green tea are on your overall health.

Clinical trials on the anti-hypercholesterolemia action of black tea and green tea were investigated in patients with high cholesterol levels in randomized, double-bind, and placebo studies. The cholesterol-lowering effect of tea extracts was evaluated by measuring biochemical parameters (i.e., LDL content and total cholesterol) and antioxidant content. Both clinical studies with black tea demonstrated its effectiveness of reducing LDL/HDL ratio, total cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and oxidative stress. In one of these clinical trials, the effective dose was 2.5 g black tea and phytosterol mixture which contains 1 g plant sterols for 4 weeks 77. However, for the other study, a specific dose is not specified, but five cups of black tea per day for two 4-week treatment periods 78. On the other hand, the consumption of “Benifuuki” green tea, which is rich in methylated catechins (3 g of green tea extract/three times daily for 12 weeks) contributed significantly to reduce serum total cholesterol and serum LDL cholesterol compared to “Yabukita” green tea or barley infusion (placebo tea) consumers 79.

Can green tea help prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease?

Evidence of a positive link between drinking green tea and Alzheimer’s disease is weak. A 2010 laboratory study 80 using animal cells found a green tea preparation rich in antioxidants protected against the nerve cell death associated with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Whether these lab results can be reproduced in human trials remains to be seen. As such, the findings do not conclusively show green tea combats Alzheimer’s disease.

Can green tea prevent tooth decay?

A small study from 2014 81 looked at how effective a green tea mouthwash was in preventing tooth decay compared with the more commonly used antibacterial mouthwash chlorhexidine. The results suggested they were equally effective, though green tea mouthwash has the added practical advantage of being cheaper.

Is green tea safe?

Tea as a food item is generally recognized as safe by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Green tea is believed to be safe when consumed as a beverage in amounts up to 8 cups per day 82. Green tea contains caffeine. Keep in mind that only the amount of added caffeine must be stated on product labels and not the caffeine that naturally occurs in green tea. The amount of caffeine present in tea varies by the type of tea; the caffeine content is higher in black teas, ranging from 64 to 112 mg per 8 fl oz (237 ml) serving, followed by oolong tea, which contains about 29 to 53 mg per 8 fl oz (237 ml) serving 12. Green and white teas contain slightly less caffeine, ranging from 24 to 39 mg per 8 fl oz (237 ml) serving and 32 to 37 mg per 8 fl oz (237 ml) serving, respectively 83. Decaffeinated teas contain less than 12 mg caffeine per 8 fl oz (237 ml) serving 83. As with other caffeinated beverages, such as coffee and colas, the caffeine contained in many tea products could potentially cause adverse effects, including tachycardia, palpitations, insomnia, restlessness, nervousness, tremors, headache, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and diuresis (excessive production of urine) 84. However, there is little evidence of health risks for adults consuming moderate amounts of caffeine (about 300 to 400 mg per day). A review by Health Canada concluded that moderate caffeine intakes of up to 400 mg per day (equivalent to 6 mg per kilogram [kg] body weight) were not associated with adverse effects in healthy adults 85. Drinking green tea may be safe during pregnancy and while breastfeeding when consumed in amounts up to 6 cups per day (no more than about 300 mg of caffeine). Drinking more than this amount during pregnancy may be unsafe and may increase the risk of negative effects. Green tea may also increase the risk of birth defects associated with folic acid deficiency 82. Caffeine passes into breast milk and can affect a breastfeeding infant. Research on the effects of caffeine in children is limited 84. In general, caffeine doses of less than 3.0 mg per kg body weight have not resulted in adverse effects in children 84. Higher doses have resulted in some behavioral effects, such as increased nervousness or anxiety and sleep disturbances 85.

Aluminum, a neurotoxic element, is found in varying quantities in tea plants 86. Studies have found concentrations of aluminum (which is naturally taken up from soil) in infusions of green and black teas that range from 14 to 27 micrograms per liter (μg/L) to 431 to 2239 μg/L 12. The variations in aluminum content may be due to different soil conditions, different harvesting periods, and water quality 12. Aluminum can accumulate in the body and cause osteomalacia and neurodegenerative disorders, especially in individuals with renal failure 12. However, it is not clear how much of the aluminum in tea is bioavailable, and there is no evidence of any aluminum toxicity associated with drinking tea 12.

Black and green tea may inhibit iron bioavailability from the diet 12. This effect may be important for individuals who suffer from iron-deficiency anemia 12. The authors of a systematic review of 35 studies on the effect of black tea drinking on iron status in the UK concluded that, although tea drinking limited the absorption of non-heme iron from the diet, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that this would have an effect on blood measures (i.e., hemoglobin and ferritin concentrations) of overall iron status in adults 87. However, among preschool children, statistically significant relationships were observed between tea drinking and poor iron status 87. The interaction between tea and iron can be mitigated by consuming, at the same meal, foods that enhance iron absorption, such as those that contain vitamin C (e.g., lemons), and animal foods that are sources of heme iron (e.g., red meat) 12. Consuming tea between meals appears to have a minimal effect on iron absorption 12.

Safety studies have looked at the consumption of up to 1200 mg of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in supplement form in healthy adults over 1- to 4-week time periods 88, 89. The adverse effects reported in these studies included excess intestinal gas, nausea, heartburn, stomach ache, abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, and muscle pain 88, 89. In a Japanese study, children aged 6 to 16 years consumed a green tea beverage containing 576 mg catechins (experimental group) or 75 mg catechins (control group) for 24 weeks with no adverse effects 90. The safety of higher doses of catechins in children is not known.

Green tea is an ingredient in many over-the-counter weight loss products, some of which have been identified as the likely cause of rare cases of liver injury. Although uncommon, liver problems have been reported in a number of people who took concentrated green tea extracts in pill form 91. More than 100 instances of clinically apparent liver injury attributed to green tea extract have been reported in the literature 91. Liver injury typically arises within 1 to 6 months of starting the product but longer and shorter latencies (particularly with reexposure) have been reported. The majority of cases present with an acute hepatitis-like syndrome and a markedly hepatocellular pattern of serum enzyme elevations. Most patients recover rapidly upon stopping the green tea extract or the herbal and dietary supplements, although fatal instances of acute liver failure have been described 91. Biopsy findings show necrosis, inflammation, and eosinophils in a pattern resembling acute hepatitis. Immunoallergic and autoimmune features are usually absent or minimal. A small number of similar cases have also been described after drinking green tea “infusions” rather than taking oral preparations of extracts of green tea. Experts suggest that green tea extracts should be taken with food, people with liver problems or liver disease should not take green tea extracts, and users should discontinue use and consult a health care provider if they develop symptoms of liver trouble, such as abdominal pain, dark urine, or jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes).

Based on the available data on the potential adverse effects of green tea catechins on the liver, the European Commission to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the Scientific Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food 2 concluded that there is evidence from interventional clinical trials that intake of green tea extracts at doses equal or above 800 mg EGCG/day taken as a food supplement for 4 months or longer has been shown to induce a statistically significant increase of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (commonly found in liver damage or liver disease) in treated subjects (usually less than 10%) compared to control 2.

Catechins in green tea extracts, either consumed as a beverage or in liquid or dry form as dietary supplements, may be more concentrated, may differ in composition and pattern of consumption compared to catechins from traditional green tea infusions and cannot be regarded as safe according to the presumption of safety approach, as exposure to green tea extracts at and above 800 mg EGCG/day in intervention studies causes elevated serum transaminases which is indicative of liver injury.

The European Commission to the European Food Safety Authority Panel concluded that it was not possible to identify an EGCG dose from green tea extracts that could be considered safe. From the clinical studies reviewed there is no evidence of hepatotoxicity (liver damage) below 800 mg EGCG/day up to 12 months. However, hepatotoxicity (liver damage) was reported for one specific product containing 80% ethanolic extract at a daily dose corresponding to 375 mg EGCG.

Green tea at high doses has also been shown to reduce blood levels and therefore the effectiveness of the drug nadolol, a beta-blocker used for high blood pressure and heart problems. It may also interact with other medicines.

Green tea summary

Green tea extracts haven’t been shown to produce a meaningful weight loss in overweight or obese adults. They also haven’t been shown to help people maintain a weight loss.

Desirable green tea intake is 3 to 5 cups per day (up to 1200 ml/day), providing a minimum of 250 mg/day catechins. If not exceeding the daily recommended allowance, those who enjoy a cup of green tea should continue its consumption. Drinking green tea appears to be safe at moderate, regular and habitual use.

If you like a cup of tea with your morning toast or afternoon snack or on its own, enjoy it. It’s safe to drink as long as you don’t add sugar or artificial sweeteners and the caffeine doesn’t make you feel jittery and shaky; interfere with sleep; and cause headaches. And the limited evidence currently available suggests that both green and black tea might have beneficial effects on some heart disease risk factors, including blood pressure and cholesterol.

Just don’t expect miracles to come in a teacup toward your weight-loss goals. Real weight loss requires a whole lifestyle approach that includes diet changes and activity.

Liver problems have been reported in a small number of people who took concentrated green tea extracts. Although the evidence that the green tea products caused the liver problems is not conclusive, experts suggest that concentrated green tea extracts be taken with food and that people discontinue use and consult a health care provider if they have a liver disorder or develop symptoms of liver trouble, such as abdominal pain, dark urine, or jaundice.

Tea has long been regarded as an aid to good health, and many believe it can help reduce the risk of cancer. Most studies of tea and cancer prevention have focused on green tea 50. Although tea and/or tea polyphenols have been found in animal studies to inhibit tumorigenesis at different organ sites, including the skin, lung, oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, liver, pancreas, and mammary gland, the results of human studies—both epidemiologic and clinical studies—have been inconclusive. Therefore we have to say that at present, with respect to tea and green tea and cancer prevention, the evidence regarding the potential benefits of tea consumption in relation to cancer is inconclusive.

- Kapoor M.P., Okubo T., Rao T.P., Juneja L.R. Green Tea Polyphenols: Nutraceuticals of Modern Life. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2013. Green Tea Polyphenols in Food and Nonfood Applications; pp. 315–335.[↩]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS), Younes M, Aggett P, Aguilar F, Crebelli R, Dusemund B, Filipič M, Frutos MJ, Galtier P, Gott D, Gundert-Remy U, Lambré C, Leblanc JC, Lillegaard IT, Moldeus P, Mortensen A, Oskarsson A, Stankovic I, Waalkens-Berendsen I, Woutersen RA, Andrade RJ, Fortes C, Mosesso P, Restani P, Arcella D, Pizzo F, Smeraldi C, Wright M. Scientific opinion on the safety of green tea catechins. EFSA J. 2018 Apr 18;16(4):e05239. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5239[↩][↩][↩]

- Preedy VR. Processing and Impact on Antioxidants in Beverages. Elsevier, 2014. DOI: 10.1016/C2012-0-02151-5[↩]

- Green tea. Altern Med Rev. 2000 Aug;5(4):372-5. https://altmedrev.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/v5-4-372.pdf[↩]

- FAO Intergovernmental Group on Tea. Emerging trends in tea consumption: informing a generic promotion process; 23rd Session of the Intergovernmental Group on Tea 2018.[↩]

- FAO Intergovernmental Group on Tea: A Subsidiary Body of the FAO Committee on Commodity Problems (CCP). World tea production and trade current and future development. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2015.[↩]

- Seeram NP, Henning SM, Niu Y, Lee R, Scheuller HS, Heber D. Catechin and caffeine content of green tea dietary supplements and correlation with antioxidant capacity. J Agric Food Chem. 2006 Mar 8;54(5):1599-603. doi: 10.1021/jf052857r[↩][↩][↩]

- Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. Tea polyphenols: prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Jun;71(6 Suppl):1698S-702S; discussion 1703S-4S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1698S[↩][↩]

- Cabrera C, Giménez R, López MC. Determination of tea components with antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2003 Jul 16;51(15):4427-35. doi: 10.1021/jf0300801[↩][↩][↩]

- Filippini T, Tancredi S, Malagoli C, Cilloni S, Malavolti M, Violi F, Vescovi L, Bargellini A, Vinceti M. Aluminum and tin: Food contamination and dietary intake in an Italian population. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019 Mar;52:293-301. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2019.01.012[↩]

- Milani RF, Silvestre LK, Morgano MA, Cadore S. Investigation of twelve trace elements in herbal tea commercialized in Brazil. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019 Mar;52:111-117. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2018.12.004[↩]

- Cabrera C, Artacho R, Giménez R. Beneficial effects of green tea–a review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006 Apr;25(2):79-99. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719518[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Peluso I, Serafini M. Antioxidants from black and green tea: from dietary modulation of oxidative stress to pharmacological mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2017 Jun;174(11):1195-1208. doi: 10.1111/bph.13649[↩][↩]

- Chen PC, Chang FS, Chen IZ, Lu FM, Cheng TJ, Chen RL. Redox potential of tea infusion as an index for the degree of fermentation. Anal Chim Acta. 2007 Jun 26;594(1):32-6. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.05.012[↩]

- Blumenthal M. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. Published by the American Botanical Council, 2003. ISBN: 9781588901576[↩]

- Sharpe E, Hua F, Schuckers S, Andreescu S, Bradley R. Effects of brewing conditions on the antioxidant capacity of twenty-four commercial green tea varieties. Food Chem. 2016 Feb 1;192:380-7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.005[↩]

- Chen Z, Zhu QY, Tsang D, Huang Y. Degradation of green tea catechins in tea drinks. J Agric Food Chem. 2001 Jan;49(1):477-82. doi: 10.1021/jf000877h[↩]

- Peterson J, Dwyer J, Jacques P, et al. Tea variety and brewing techniques influence flavonoid content of black tea. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2004; 17(3–4):397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2004.03.022[↩][↩]

- Arts IC, van De Putte B, Hollman PC. Catechin contents of foods commonly consumed in The Netherlands. 2. Tea, wine, fruit juices, and chocolate milk. J Agric Food Chem. 2000 May;48(5):1752-7. doi: 10.1021/jf000026+[↩]

- Henning SM, Fajardo-Lira C, Lee HW, Youssefian AA, Go VL, Heber D. Catechin content of 18 teas and a green tea extract supplement correlates with the antioxidant capacity. Nutr Cancer. 2003;45(2):226-35. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4502_13[↩]

- Chen M, Wang F, Cao JJ, Han X, Lu WW, Ji X, Chen WH, Lu WQ, Liu AL. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates the toxicity of methylmercury in Caenorhabditis elegans by activating SKN-1. Chem Biol Interact. 2019 Jul 1;307:125-135. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.029[↩]

- Rashidi B, Malekzadeh M, Goodarzi M, Masoudifar A, Mirzaei H. Green tea and its anti-angiogenesis effects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 May;89:949-956. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.161[↩]

- Shirakami Y, Shimizu M. Possible Mechanisms of Green Tea and Its Constituents against Cancer. Molecules. 2018 Sep 7;23(9):2284. doi: 10.3390/molecules23092284[↩]

- Xu XY, Zhao CN, Cao SY, Tang GY, Gan RY, Li HB. Effects and mechanisms of tea for the prevention and management of cancers: An updated review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(10):1693-1705. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1588223[↩]

- Farrar MD, Nicolaou A, Clarke KA, Mason S, Massey KA, Dew TP, Watson RE, Williamson G, Rhodes LE. A randomized controlled trial of green tea catechins in protection against ultraviolet radiation-induced cutaneous inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Sep;102(3):608-15. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.107995[↩]

- Farrar MD, Huq R, Mason S, Nicolaou A, Clarke KA, Dew TP, Williamson G, Watson REB, Rhodes LE. Oral green tea catechins do not provide photoprotection from direct DNA damage induced by higher dose solar simulated radiation: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Feb;78(2):414-416. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.021[↩]

- Kapoor MP, Sugita M, Fukuzawa Y, Timm D, Ozeki M, Okubo T. Green Tea Catechin Association with Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced Erythema: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Molecules. 2021 Jun 17;26(12):3702. doi: 10.3390/molecules26123702[↩]

- Ryan L, Petit S. Addition of whole, semiskimmed, and skimmed bovine milk reduces the total antioxidant capacity of black tea. Nutr Res. 2010;30:14-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20116655[↩][↩]

- Arts MJ, Haenen GR, Wilms LC, et al. Interactions between flavonoids and proteins: effect on the total antioxidant capacity. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:1184-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11853501[↩]

- Reto M, Figueira ME, Filipe HM, Almeida CM. Chemical composition of green tea (Camellia sinensis) infusions commercialized in Portugal. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2007 Dec;62(4):139-44. doi: 10.1007/s11130-007-0054-8[↩]

- Wu AH, Yu MC. Tea, hormone-related cancers and endogenous hormone levels. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research 2006; 50(2):160–169. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16470648[↩]

- Mukhtar H, Ahmad N. Tea polyphenols: Prevention of cancer and optimizing health. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000; 71(6 Suppl):1698S–1702S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10837321[↩]

- Santana-Rios G, Orner GA, Xu M, Izquierdo-Pulido M, Dashwood RH. Inhibition by white tea of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine-induced colonic aberrant crypts in the F344 rat. Nutrition and Cancer 2001; 41(1 and 2):98–103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12094635[↩]

- Chen ZY, Zhu QY, Tsang D, Huang Y. Degradation of green tea catechins in tea drinks. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2001; 49(1):477–482. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11170614[↩]

- Cabrera C, Giménez R, López MC. Determination of tea components with antioxidant activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003; 51(15):4427–4435. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12848521[↩][↩]

- Peterson J, Dwyer J, Jacques P, et al. Tea variety and brewing techniques influence flavonoid content of black tea. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2004; 17(3–4):397–405. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889157504000614[↩][↩]

- Arts ICW, van de Putte B, Hollman PCH. Catechin contents of foods commonly consumed in the Netherlands. 2. Tea, wine, fruit juices, and chocolate milk. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2000; 48(5):1752–1757. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10820090[↩]

- Henning SM, Fajardo-Lira C, Lee HW, et al. Catechin content of 18 teas and a green tea extract supplement correlates with the antioxidant capacity. Nutrition and Cancer 2003; 45(2):226–235. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12881018[↩]

- Seeram NP, Henning SM, Niu Y, et al. Catechin and caffeine content of green tea dietary supplements and correlation with antioxidant capacity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2006; 54(5):1599–1603. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/jf052857r[↩][↩]

- GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jul 6;377(1):13-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362[↩]

- Blüher M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019;15:228–298. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8[↩]

- Jurgens TM, Whelan AM, Killian L, Doucette S, Kirk S, Foy E. Green tea for weight loss and weight maintenance in overweight or obese adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD008650. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008650.pub2. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008650.pub2[↩][↩][↩]

- Chen I.J., Liu C.Y., Chiu J.P., Hsu C.H. Therapeutic effect of high-dose green tea extract on weight reduction: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2016;35:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.05.003[↩]

- Huang LH, Liu CY, Wang LY, Huang CJ, Hsu CH. Effects of green tea extract on overweight and obese women with high levels of low density-lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C): a randomised, double-blind, and cross-over placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018 Nov 6;18(1):294. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2355-x[↩]

- Dostal A.M., Arikawa A., Espejo L., Kurzer M.S. Long-term supplementation of green tea extract does not modify adiposity or bone mineral density in a randomized trial of overweight and obese postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2016;46:256–264. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.219238[↩]

- Janssens P.L., Hursel R., Westerterp-Plantenga M.S. Long-term green tea extract supplementation does not affect fat absorption, resting energy expenditure, and body composition in adults. Nutr. J. 2015;145:864–870. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.207829[↩]

- Nicoletti CF, Delfino HBP, Pinhel M, Noronha NY, Pinhanelli VC, Quinhoneiro DCG, de Oliveira BAP, Marchini JS, Nonino CB. Impact of green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate on HIF1-α and mTORC2 expression in obese women: anti-cancer and anti-obesity effects? Nutr Hosp. 2019 Apr 10;36(2):315-320. English. doi: 10.20960/nh.2216[↩]

- Henning SM, Niu Y, Lee NH, et al. Bioavailability and antioxidant activity of tea flavanols after consumption of green tea, black tea, or a green tea extract supplement. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004; 80(6):1558–1564. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/80/6/1558.long[↩][↩]

- Seeram NP, Henning SM, Niu Y, et al. Catechin and caffeine content of green tea dietary supplements and correlation with antioxidant capacity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2006; 54(5):1599–1603. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jf052857r[↩]

- Lambert JD, Yang CS. Mechanisms of cancer prevention by tea constituents. Journal of Nutrition 2003; 133(10):3262S–3267S. http://jn.nutrition.org/content/133/10/3262S.long[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Lee AH, Su D, Pasalich M, Binns CW. Tea consumption reduces ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:54-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23107758[↩]

- Nechuta S, Shu XO, Li HL, et al. Prospective cohort study of tea consumption and risk of digestive system cancers: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1056-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3471195/[↩]

- Johnson R, Bryant S, Huntley AL. Green tea and green tea catechin extracts: an overview of the clinical evidence. Maturitas. 2012;73:280-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22986087[↩]

- Zaveri NT. Green tea and its polyphenolic catechins: Medicinal uses in cancer and noncancer applications. Life Sciences 2006; 78(18):2073–2080. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16445946[↩]

- Elmets CA, Singh D, Tubesing K, et al. Cutaneous photoprotection from ultraviolet injury by green tea polyphenols. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2001; 44(3):425–432. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11209110[↩]

- Steele VE, Kelloff GJ, Balentine D, et al. Comparative chemopreventive mechanisms of green tea, black tea and selected polyphenol extracts measured by in vitro bioassays. Carcinogenesis 2000; 21(1):63–67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10607735[↩][↩]

- Yang CS, Maliakal P, Meng X. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2002; 42:25–54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11807163[↩]

- Boehm K, Borrelli F, Ernst E, Habacher G, Hung SK, Milazzo S, Horneber M. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005004. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005004.pub2. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005004.pub2/full[↩]

- Lambert JD, Yang CS. Mechanisms of cancer prevention by tea constituents. Journal of Nutrition 2003; 133(10):3262S–3267S , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14519824[↩]

- Self-assembled micellar nanocomplexes comprising green tea catechin derivatives and protein drugs for cancer therapy. Nature Nanotechnology volume 9, pages 907–912 (2014) https://www.nature.com/articles/nnano.2014.208[↩]

- Kuriyama S, Shimazu T, Ohmori K, et al. Green tea consumption and mortality due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in Japan: the Ohsaki study. JAMA. 2006;296:1255-65. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/203337[↩]

- Larsson SC, Virtamo J, Wolk A. Black tea consumption and risk of stroke in women and men. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:157-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23295000[↩]

- Mineharu Y, Koizumi A, Wada Y, et al. Coffee, green tea, black tea and oolong tea consumption and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease in Japanese men and women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:230-40. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19996359[↩]

- Arab L, Liu W, Elashoff D. Green and black tea consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:1786-92. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/40/5/1786.long[↩]

- Yang YC, Lu FH, Wu JS, Wu CH, Chang CJ. The protective effect of habitual tea consumption on hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1534-40. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15277285[↩]

- Hodgson JM, Puddey IB, Woodman RJ, et al. Effects of black tea on blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:186-8. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1108657[↩]

- http://www.cochrane.org/CD009934/VASC_green-and-black-tea-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease[↩]

- Mahmoud F., Al-Ozairi E., Haines D., Novotny L., Dashti A., Ibrahim B., Abdel-Hamid M. Effect of Diabetea tea™ consumption on inflammatory cytokines and metabolic biomarkers in type 2 diabetes patients. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.073[↩]

- Stepien M, Kujawska-Luczak M, Szulinska M, Kregielska-Narozna M, Skrypnik D, Suliburska J, Skrypnik K, Regula J, Bogdanski P. Beneficial dose-independent influence of Camellia sinensis supplementation on lipid profile, glycemia, and insulin resistance in an NaCl-induced hypertensive rat model. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018 Apr;69(2). doi: 10.26402/jpp.2018.2.13[↩]

- Yousaf S, Butt MS, Suleria HA, Iqbal MJ. The role of green tea extract and powder in mitigating metabolic syndromes with special reference to hyperglycemia and hypercholesterolemia. Food Funct. 2014 Mar;5(3):545-56. doi: 10.1039/c3fo60203f[↩]

- Li SB, Li YF, Mao ZF, Hu HH, Ouyang SH, Wu YP, Tsoi B, Gong P, Kurihara H, He RR. Differing chemical compositions of three teas may explain their different effects on acute blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Sci Food Agric. 2015 Apr;95(6):1236-42. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6811[↩]

- Miltonprabu S., Thangapandiyan S. Epigallocatechin gallate potentially attenuates Fluoride induced oxidative stress mediated cardiotoxicity and dyslipidemia in rats. J. Trace. Elem. Med. Biol. 2015;29:321–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.08.015[↩]

- Nomura S., Monobe M., Ema K., Matsunaga A., Maeda-Yamamoto M., Horie H. Effects of flavonol-rich green tea cultivar (Camellia sinensis L.) on plasma oxidized LDL levels in hypercholesterolemic mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016;80:360–362. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1083400[↩]

- Paudel K.R., Lee U.W., Kim D.W. Chungtaejeon, a Korean fermented tea, prevents the risk of atherosclerosis in rats fed a high-fat atherogenic diet. J. Integr. Med. 2016;14:134–142. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(16)60249-2[↩]

- Hartley L, Flowers N, Holmes J, Clarke A, Stranges S, Hooper L, Rees K. Green and black tea for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD009934. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009934.pub2. http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009934.pub2/full[↩]

- Green tea catechins decrease total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 Nov;111(11):1720-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.009. https://jandonline.org/article/S0002-8223(11)01379-4/fulltext[↩]

- Orem A., Alasalvar C., Kural B.V., Yaman S., Orem C., Karadag A., Zawistowski J. Cardio-protective effects of phytosterol-enriched functional black tea in mild hypercholesterolemia subjects. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;31:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.01.048[↩]

- Troup R, Hayes JH, Raatz SK, Thyagarajan B, Khaliq W, Jacobs DR Jr, Key NS, Morawski BM, Kaiser D, Bank AJ, Gross M. Effect of black tea intake on blood cholesterol concentrations in individuals with mild hypercholesterolemia: a diet-controlled randomized trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Feb;115(2):264-271.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.07.021[↩]

- Imbe H., Sano H., Miyawaki M., Fujisawa R., Miyasato M., Nakatsuji F., Tachibana H. “Benifuuki” green tea, containing O-methylated EGCG, reduces serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 ligands containing apolipoprotein B: A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;25:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.05.004[↩]

- In vitro protective effects of colon-available extract of Camellia sinensis (tea) against hydrogen peroxide and beta-amyloid (Aβ((1-42) induced cytotoxicity in differentiated PC12 cells. Phytomedicine. 2011 Jun 15;18(8-9):691-6. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.11.004. Epub 2010 Dec 22. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0944711310003971[↩]

- Effects of Green Tea on Streptococcus mutans Counts-A Randomised Control Trail. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4290345/pdf/jcdr-8-127-ZC128.pdf[↩]

- Green Tea. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/green-tea[↩][↩]

- Jenna M. Chin, Michele L. Merves, Bruce A. Goldberger, Angela Sampson-Cone, Edward J. Cone, Caffeine Content of Brewed Teas, Journal of Analytical Toxicology, Volume 32, Issue 8, October 2008, Pages 702–704, https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/32.8.702[↩][↩]

- Higdon JV, Frei B. Coffee and health: a review of recent human research. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2006;46(2):101-23. doi: 10.1080/10408390500400009[↩][↩][↩]

- Nawrot P, Jordan S, Eastwood J, Rotstein J, Hugenholtz A, Feeley M. Effects of caffeine on human health. Food Addit Contam. 2003 Jan;20(1):1-30. doi: 10.1080/0265203021000007840[↩][↩]

- Tea and Cancer Prevention. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/diet/tea-fact-sheet[↩]

- Nelson, M. and Poulter, J. (2004), Impact of tea drinking on iron status in the UK: a review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 17: 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00497.x[↩][↩]

- Chow HH, Hakim IA, Vining DR, Crowell JA, Ranger-Moore J, Chew WM, Celaya CA, Rodney SR, Hara Y, Alberts DS. Effects of dosing condition on the oral bioavailability of green tea catechins after single-dose administration of Polyphenon E in healthy individuals. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Jun 15;11(12):4627-33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2549[↩][↩]

- Chow HH, Cai Y, Hakim IA, Crowell JA, Shahi F, Brooks CA, Dorr RT, Hara Y, Alberts DS. Pharmacokinetics and safety of green tea polyphenols after multiple-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E in healthy individuals. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Aug 15;9(9):3312-9.[↩][↩]

- Matsuyama, T., Tanaka, Y., Kamimaki, I., Nagao, T. and Tokimitsu, I. (2008), Catechin Safely Improved Higher Levels of Fatness, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol in Children. Obesity, 16: 1338-1348. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.60[↩]

- LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Green Tea. [Updated 2020 Nov 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547925[↩][↩][↩]