What is berylliosis

Berylliosis is also known as chronic beryllium disease, is a granulomatous disease caused by exposure to beryllium, who develop beryllium sensitization (BeS), a cell-mediated immune response to environmental and occupational beryllium exposure 1. Acute beryllium disease and chronic beryllium disease (berylliosis) are caused by inhalation of dust or fumes from beryllium compounds and products. Acute beryllium disease is now rare; chronic beryllium disease is characterized by formation of granulomas throughout the body, especially in the lungs, intrathoracic lymph nodes, and skin. Berylliosis has a variable clinical course with cough, fever, night sweats, and fatigue being the most common symptoms 2. Beryllium sensitization precedes the lung disease that may present with chronic dry cough, fatigue, weight loss, chest pain, and increasing dyspnea. Definitive diagnosis of berylliosis is based on occupational history, positive blood or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT), and granulomatous inflammation on lung biopsy 3.

Beryllium exposure is a common but underrecognized cause of illness in many industries, including beryllium mining and extraction, alloy production, metal alloy machining, electronics, telecommunications, nuclear weapon manufacture, defense, aircraft, automotive, aerospace, and metal scrap, computer, and electronics recycling. Because small amounts of beryllium are toxic and are added to many copper, aluminum, nickel, and magnesium alloys, workers are often unaware of their exposure and its risks.

The number of workers exposed to beryllium has been estimated at 1 million in the US, although no accurate figure exists for the US or globally. The prevalence of sensitization in those exposed ranges from 1 – 20%. Berylliosis or chronic beryllium disease among those with beryllium sensitization ranges from 15-100%. The current Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) guidelines reduce the permissible exposure limit for beryllium to 0.2 mcg/m³ averaged over 8 hours or less than 2 mcg/m³ over a 15 minute period. It is an incurable occupational lung disease, but symptoms can be treated with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents 4. Berylliosis treatment is with corticosteroids.

Berylliosis vs Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disorder resulting in noncaseating granulomas in one or more organs and tissues, usually in your lungs, skin, or lymph nodes. The cause of sarcoidosis is unknown. The lungs and lymphatic system are most often affected, but sarcoidosis may affect any organ. It affects men and women of all ages and races. Sarcoidosis occurs mostly in people ages 20 to 50, African Americans, especially women, and people of Northern European origin.

Many people with sarcoidosis have no symptoms. If you have symptoms, they may include:

- Cough

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

- Weight loss

- Night sweats

- Fatigue

- Lung or other organ failure (rarely)

Diagnosis usually is first suspected because of lung involvement and is confirmed by chest x-ray, biopsy, and exclusion of other causes of granulomatous inflammation. Berylliosis may be pathologically and clinically indistinguishable from pulmonary sarcoidosis, except through use of immunologic testing, such as the beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT).

Not everyone who has the disease needs treatment. If you do, first-line treatment is corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone). Prognosis is excellent for limited disease but poor for more advanced disease.

Berylliosis causes

Berylliosis is caused by occupational exposure to beryllium and beryllium-containing alloys (usually by inhalation of dust or fumes but also via contact with skin). Over time, in a subset of individuals, a cell-mediated immune response to beryllium may occur, causing the development of sensitized T cells that accumulate within the lungs and eventually form granulomas which can lead to fibrosis. A genetic variant in the HLA-DPB1 gene (6p21.3) with the presence of a glutamic acid at amino acid position 69 has been associated with the development of beryllium sensitization and berylliosis.

Berylliosis pathophysiology

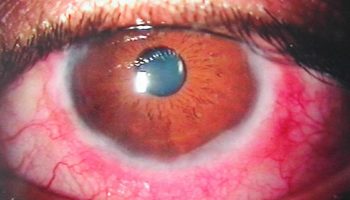

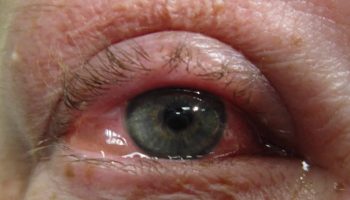

Acute beryllium disease is a chemical pneumonitis causing diffuse parenchymal inflammatory infiltrates and nonspecific intra-alveolar edema. Other tissues (eg, skin, conjunctivae) may be affected. Acute beryllium disease is now rare because most industries have reduced exposure levels, but cases were common between 1940 and 1970, and many cases progressed from acute to chronic beryllium disease.

Chronic beryllium disease (berylliosis) remains a common illness in industries that use beryllium and beryllium alloy. It differs from most pneumoconioses in that it is a cell-mediated hypersensitivity disease. Beryllium is presented to CD4+ T cells by antigen-presenting cells, principally in HLA-DP molecules. T cells in the blood, lungs, or other organs, in turn, recognize the beryllium, proliferate, and form T-cell clones. These clones then release proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-2, and interferon-gamma. These cytokines amplify the immune response, resulting in formation of mononuclear cell infiltrates and noncaseating granulomas in target organs where beryllium has deposited.

On average, about 2% to 6% of beryllium-exposed people develop beryllium sensitization (defined by positive blood lymphocyte proliferation to beryllium salts in vitro), with most progressing to disease. In certain high-risk groups, such as beryllium metal and alloy machinists, chronic beryllium disease prevalence is > 17%. Workers with bystander exposures, such as secretaries and security guards, also develop sensitization and disease but at lower rates. The typical pathologic consequence is a diffuse pulmonary, hilar, and mediastinal lymph node granulomatous reaction that is histologically indistinguishable from sarcoidosis. Early granuloma formation with mononuclear and giant cells can also occur. Many lymphocytes are found when cells are washed from the lungs (bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL]) during bronchoscopy. These T cells proliferate when exposed to beryllium in vitro, much as the blood cells do (a test called beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test [BeLPT]).

Berylliosis prevention

Industrial dust suppression is the basis for preventing beryllium exposure. Berylliosis may be prevented by providing exposed workers with respiratory protective devices and protective clothing and by minimizing exposure through use of workplace administration and engineering controls. Exposure must be limited to levels that are as low as reasonably achievable; 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter of air, averaged over 8 hours and limited short-term exposure to 2.0 micrograms per cubic meter of air, over a 15-min sampling period.

Medical surveillance, using blood beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test [BeLPT] and chest x-ray, is recommended for all exposed workers, including those with indirect contact. The beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT) is used to identify patients early on and to define workplace areas for modification in order to ultimately reduce additional beryllium sensitization and berylliosis cases.

Both acute and chronic disease must be promptly recognized and affected workers removed from further beryllium exposure.

Berylliosis symptoms

Patients with chronic beryllium disease (berylliosis) can range from those who are asymptomatic to those with severe lung dysfunction. Manifestations occur a few months to a many years (> 30 years) after exposure has ceased to beryllium and include chronic dry cough, dyspnea on exertion, chest pain, fatigue, fever, night sweats and weight loss. Additional extrapulmonary manifestations of dermatitis and skin granulomas have been reported. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis can eventually lead to cor pulmonale and respiratory failure. Chest x-ray pattern typically showing nodular opacities in the mid and upper lung zones, frequently with hilar and mediastinal adenopathy. An increased risk of lung cancer among workers exposed to high levels of beryllium has also been observed.

Berylliosis diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on a history of exposure to beryllium, characteristic clinical findings and laboratory testing. Beryllium sensitization can be detected with the beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT) where mononuclear cells from peripheral blood or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) are exposed to beryllium in vitro. Increased proliferation of lymphocytes compared to control cells indicates beryllium sensitization. Granulomatous and/or mononuclear cell infiltrates in lung tissue, are indicative of berylliosis. Chest x-ray, CT scan of the lungs, exercise tolerance testing and pulmonary function tests can also aid in the diagnosis.

Acute beryllium disease is distinguished from chronic berylliosis based on history of a very high level of exposure followed by acute onset of dry cough and progressive dyspnea on exertion in addition to systematic signs and symptoms (conjunctivitis, dermatitis, pharyngitis, laryngotracheobronchitis). Further, radiographic findings occur within 1 to 3 weeks of exposure. In chronic beryllium disease, the signs and symptoms are present for at least a year and the clinical presentation can be varied from asymptomatic to dry cough, progressive dyspnea, fatigue, and night sweats 5. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT) is highly sensitive and specific, helping to distinguish chronic beryllium disease from sarcoidosis and other forms of diffuse pulmonary disease. Because serum angiotensin converting enzyme levels are not sensitive and, when positive, fail to distinguish between exposure and disease, these levels are not routinely measured 6.

Chest x-ray may be normal or show diffuse infiltrates that can be nodular, reticular, or have a hazy ground-glass appearance, often with hilar adenopathy resembling the pattern seen in sarcoidosis. A miliary pattern also occurs. High-resolution (thin-section) CT is more sensitive than x-ray, although cases of biopsy-proven disease occur even in people with normal imaging test results.

Berylliosis treatment

There is no cure for berylliosis and the goals when treating berylliosis are to reduce symptoms and slow the progression of the disease. Treatment involves cessation of beryllium exposure and use of corticosteroids (prednisone). Although there is no evidence that stopping exposure to beryllium decreases the progression of berylliosis, they still consider it to be an accepted approach to treatment. People with early stages, without lung function abnormalities or clinical symptoms are periodically monitored, with physical exams, pulmonary function tests, and radiography. Early symptomatic disease may be treated with inhaled corticosteroids along with a short acting bronchodilator. Methotrexate and other immunosuppressive therapies can reduce steroid side effects. The efficacy of corticosteroids may be limited and relapses can occur after cessation of therapy or when dose is lowered. All patients require influenza and pneumococcal vaccination and smoking cessation counseling. Those with advanced disease and major breathing difficulties may require oxygen supplementation. In severe cases, a lung transplant may be suggested. Patients should refrain from smoking.

The drugs of choice to treat chronic beryllium disease are corticosteroids. It usually requires a high starting dose and the treatment duration is often for several months before they see symptom resolution. Once symptoms subside, tapering of the steroids is necessary to prevent the adverse effects. They can treat patients who fail to respond to steroids on immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate and azathioprine. They starts oral methotrexate at a 7.5mg weekly dose given with folic acid 1mg. Complete blood counts and liver function tests should be repeated 8 to 12 weeks at a time.

Once a diagnosis of berylliosis is made, the patient needs life-long follow up with serial arterial blood gases, chest x-ray, and pulmonary function tests 7.

Berylliosis prognosis

Berylliosis prognosis varies, with some patients remaining clinically stable for many years and some experiencing a gradual worsening of symptoms over time. A debilitating course resulting in respiratory failure is also possible but regular monitoring and treatment can slow down the disease process.

Patients with beryllium sensitization in the absence of berylliosis (chronic beryllium disease) don’t require treatment but should undergo periodic evaluation. Among these patients, the risk of progression to berylliosis is increased compared with non-sensitized workers. Overall mortality rates are 5% to 38% 8. A higher percentage of lymphocytes in the bronchoalveolar lavage correlates with a greater severity of illness 9.

Acute beryllium disease can be fatal, but prognosis is usually excellent unless progression to chronic beryllium disease occurs. Chronic beryllium disease often results in progressive loss of respiratory function. Early abnormalities include air flow obstruction and decreased oxygenation on arterial blood gas (ABG) at rest and during exercise testing. Decreased diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and restriction appear later. Pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular failure develop in about 10% of cases, with death due to cor pulmonale.

Beryllium sensitization progresses to chronic beryllium disease at a rate of about 6%/year after initial detection through workplace medical surveillance programs. Subcutaneous granulomatous nodules caused by inoculation with beryllium splinters or dust usually persist until excised.

- Beryllium disease. https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/867/berylliosis[↩]

- Sizar O, Talati R. Berylliosis (Chronic Beryllium Disease) [Updated 2019 May 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470364[↩]

- Balmes JR, Abraham JL, Dweik RA, Fireman E, Fontenot AP, Maier LA, Muller-Quernheim J, Ostiguy G, Pepper LD, Saltini C, Schuler CR, Takaro TK, Wambach PF., ATS Ad Hoc Committee on Beryllium Sensitivity and Chronic Beryllium Disease. An official American Thoracic Society statement: diagnosis and management of beryllium sensitivity and chronic beryllium disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014 Nov 15;190(10):e34-59[↩]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Department of Labor. Occupational Exposure to Beryllium. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2017 Jan 09;82(5):2470-757[↩]

- Stoeckle JD, Hardy HL, Weber AL: Chronic beryllium disease: Long-term follow-up of sixty cases and selective review of the literature. Am J Med 46 (4):545–561, 1969.[↩]

- Newman LS, Orton R, Kreiss K: Serum angiotensin converting enzyme activity in chronic beryllium disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 146 (1):39–42, 1992.[↩]

- Thomas CA, Deubner DC, Stanton ML, Kreiss K, Schuler CR. Long-term efficacy of a program to prevent beryllium disease. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013 Jul;56(7):733-41[↩]

- Newman LS, Lloyd J, Daniloff E. The natural history of beryllium sensitization and chronic beryllium disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996 Oct;104 Suppl 5:937-43[↩]

- Newman LS, Bobka C, Schumacher B, Daniloff E, Zhen B, Mroz MM, King TE. Compartmentalized immune response reflects clinical severity of beryllium disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994 Jul;150(1):135-42[↩]