Juvenile arthritis

Juvenile arthritis also known as pediatric rheumatic disease, is an umbrella term used to describe the many autoimmune and inflammatory conditions or pediatric rheumatic diseases that can develop in children under the age of 16 1. Children can get arthritis just like adults. About 294,000 American children under age 18 have arthritis or other rheumatic conditions. Arthritis is caused by inflammation of the joints. A joint is where two or more bones are joined together. Juvenile arthritis is a rheumatic disease, or one that causes loss of function due to an inflamed supporting structure or structures of the body. Juvenile arthritis causes joint swelling, pain, stiffness, and loss of motion. It can affect any joint, but is more common in the knees, hands, and feet. In some cases juvenile arthritis can affect internal organs as well. Juvenile arthritis can also involve the eyes, skin, muscles and gastrointestinal tract. It can cause other symptoms such as fevers or rash.

The most common type of arthritis in children is called juvenile idiopathic arthritis (idiopathic means “from unknown causes”). There are several other forms of arthritis affecting children. The inflammation begins before children reach the age of 16, and symptoms must last more than 6 weeks to be called chronic.

Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis affects about ten percent of children with arthritis. It begins with repeating fevers that can be 103°F or higher, often accompanied by a salmon-colored rash that comes and goes. Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis may cause inflammation of the internal organs as well as the joints, though joint swelling may not appear until months or even years after the fevers began. Anemia (a low red blood cell count) and elevated white blood cell counts are also typical findings in blood tests ordered to evaluate the fevers and ongoing symptoms. Arthritis may persist even after the fevers and other symptoms have disappeared.

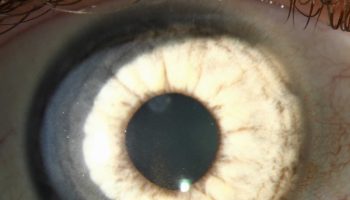

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, which involves fewer than five joints in its first stages, affects about half of all children with arthritis. Girls are more at risk than boys. Some older children with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis may develop “extended” arthritis that involves many joints and lasts into adulthood. Children who develop the oligoarticular form of juvenile idiopathic arthritis when they are younger than seven years old have the best chance of having their joint disease subside with time. They are, however, at increased risk of developing an inflammatory eye problem (iritis or uveitis). Eye inflammation may persist independently of the arthritis. Because this eye inflammation usually does not cause symptoms, regular exams by an ophthalmologist (eye doctor) are essential to detect these conditions and identify treatment to prevent vision loss.

Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis affects five or more joints and can begin at any age. Children diagnosed with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis in their teens may actually have the adult form of rheumatoid arthritis at an earlier-than-usual age.

With psoriatic arthritis, children have both arthritis and a skin disease called psoriasis or a family history of psoriasis in a parent or sibling. Typical signs of psoriatic arthritis include nail changes and widespread swelling of a toe or finger called dactylitis.

Enthesitis-related arthritis is a form of juvenile idiopathic arthritis that often involves attachments of ligaments as well as the spine. This form is sometimes called a spondyloarthritis. These children may have joint pain without obvious swelling and may complain of back pain and stiffness. There is sometimes a family history of arthritis of the spine.

Arthritis in children is treatable. The goal of treatment is to relieve inflammation, control pain and improve the child’s quality of life. Doctors who treat arthritis in children will try to make sure your child can remain physically active. They also try to make sure your child can stay involved in social activities and have an overall good quality of life.

Doctors can prescribe treatments to reduce swelling, maintain joint movement, and relieve pain. They also try to prevent, identify, and treat problems that result from the arthritis. Most children with arthritis need a blend of treatments – some treatments include medicines.

Exercise is key to reducing symptoms of juvenile arthritis and maintaining range of motion of the joints.

Researchers are also trying to improve current treatments and find new medicines that will work better with fewer side effects.

Juvenile arthritis key points

- Juvenile arthritis is the term used to describe arthritis, or inflammation of the joints, in children.

- The most common symptoms of juvenile arthritis are joint swelling, pain, and stiffness that don’t go away.

- Juvenile arthritis is usually an autoimmune disorder. In an autoimmune disorder, the immune system attacks some of the body’s own healthy cells and tissues.

- Juvenile arthritis affects children of all ages and ethnic backgrounds.

- To diagnose juvenile arthritis, a doctor may perform a physical exam, ask about family health history, and order lab or blood tests, and x-rays.

- Juvenile arthritis can make it hard to take part in social and after-school activities, and it can make schoolwork more difficult. But, all family members can help the child both physically and emotionally.

- Exercise is key to reducing the symptoms of arthritis and maintaining range of motion of the joints.

- Inflammation inside of the eye and growth problems may also occur with juvenile arthritis.

Juvenile arthritis types

There are several types of juvenile arthritis. Nearly all of them are different from rheumatoid arthritis in adults. This is why the term “juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA)” is no longer widely used.

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Considered the most common form of arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis includes six subtypes: oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, systemic, enthesitis-related, juvenile psoriatic arthritis or undifferentiated.

- Juvenile dermatomyositis. An inflammatory disease, juvenile dermatomyositis causes muscle weakness and a skin rash on the eyelids and knuckles.

- Juvenile lupus. Lupus is an autoimmune disease. The most common form is systemic lupus erythematosus, or SLE. Lupus can affect the joints, skin, kidneys, blood and other areas of the body.

- Juvenile scleroderma. Scleroderma, which literally means “hard skin,” describes a group of conditions that causes the skin to tighten and harden.

- Kawasaki disease. This disease causes blood-vessel inflammation that can lead to heart complications.

- Mixed connective tissue disease. This disease may include features of arthritis, lupus dermatomyositis and scleroderma, and is associated with very high levels of a particular antinuclear antibody called anti-RNP.

- Fibromyalgia. This chronic pain syndrome is an arthritis-related condition, which can cause stiffness and aching, along with fatigue, disrupted sleep and other symptoms. More common in girls, fibromyalgia is seldom diagnosed before puberty.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis types

There are three main types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. This classification is based on symptoms, the number of joints involved, and the presence of certain antibodies in the blood. Doctors classify juvenile idiopathic arthritis to help them predict how the disease will progress.

The three main types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis are:

- Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Oligoarticular (formerly known as pauciarticular) means “few joints.” In this type of juvenile arthritis, just a few joints are affected. About 50% of children with juvenile arthritis have the oligoarticular type. Girls younger than 8 years of age are more likely to develop it.

In half of the children with oligoarticular juvenile arthritis, only one joint is involved, usually a knee or ankle. This is called monoarticular juvenile arthritis. In most cases, this arthritis is very mild and, over time, the symptoms may lessen or go away altogether.

For some children, this arthritis affects four or fewer larger joints. Joints affected include the knee, ankle, or wrist. Involvement of fingers or toes is unusual.

Oligoarticular juvenile arthritis may also cause eye inflammation. To prevent blindness, your child may need regular eye examinations from a doctor who specializes in eye diseases (ophthalmologist). Eye problems may continue into adulthood.

Polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis

About 30% of children with juvenile arthritis have the polyarticular type. This type of arthritis is more common in girls than in boys.

Polyarticular juvenile arthritis affects five or more smaller joints (such as the hands and feet). Usually, the affected joints are on both sides of the body. This type of juvenile arthritis can also affect large joints.

Children with a certain antibody in their blood, called IgM rheumatoid factor (RF), often have a more severe form of the disease. Antibodies are proteins in the blood usually used by the body to fight off infection through an immune response. In this form of arthritis, the IgM rheumatoid factor antibody attacks the body’s own tissues. Doctors believe that this is the same type of arthritis as adult rheumatoid arthritis.

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis

About 20% of children with juvenile arthritis have the systemic type.

This type of juvenile arthritis causes swelling, pain, and limited motion in at least one joint. Additional symptoms include rash and inflammation of internal organs such as the heart, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. A fever of at least 102 degrees each day for 2 weeks or longer suggests this diagnosis.

If not adequately treated, children with systemic juvenile arthritis may develop arthritis in many joints and have severe arthritis that continues into adulthood.

Juvenile arthritis causes

Scientists are looking for the possible causes of juvenile arthritis. They are studying both genetic and environmental factors that they think are involved.

Juvenile arthritis is usually an autoimmune disorder. A healthy immune system helps a person fight off harmful bacteria and viruses. But in an autoimmune disorder, the immune system attacks some of the body’s own healthy cells and tissues. Malfunctioning of the immune system in juvenile idiopathic arthritis targets the lining of the joint, known as the synovial membrane. This causes inflammation. When the inflammation is untreated, joint damage may occur.

Arthritis results from ongoing joint inflammation in four steps:

- The joint becomes inflamed

- The joint stiffens (contracture)

- The joint suffers damage

- The joint’s growth is changed

Scientists don’t know why this happens or what causes the immune system to malfunction in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Some think that something in a child’s genes (passed from parents to children) makes the child more likely to get arthritis, and then something else, such as a virus, sets off the arthritis.

In rare cases such as in psoriatic arthritis or enthesitis-related arthritis, a parent has the same form of arthritis. Dietary and emotional factors do not appear to play a role in the development of juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Because the causes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis are unknown, no one knows how to prevent these conditions.

Juvenile arthritis symptoms

Juvenile arthritis affects each child differently and can last for indefinite periods of time. There may be times when symptoms improve or disappear (remissions). There are other times when symptoms worsen (flare-ups). Sometimes, a child may have one or two flare-ups and never have symptoms again. Other children may have frequent flare-ups and symptoms that never go away.

In some cases, symptoms of juvenile arthritis are mild and do not progress to more severe joint disease and deformities. In severe cases, juvenile arthritis can produce serious joint and tissue damage. It can also cause problems with bone development and growth.

The most common symptoms of juvenile arthritis are joint swelling, pain, and stiffness that don’t go away. Usually it affects the knees, hands, and feet, and it’s worse in the morning or after a nap. Other signs can include:

- Limping in the morning because of a stiff knee.

- Excessive clumsiness.

- High fever and skin rash.

- Swelling in lymph nodes in the neck and other parts of the body.

Most children with arthritis have times when the symptoms get better or go away (remission) and other times when they get worse (flare).

Other medical problems related to juvenile arthritis

Inflammation inside of the eye that can cause swelling, redness, and damage to the eye tissue is a severe medical problem that can occur in children with juvenile arthritis. Sometimes there are no symptoms, so all children with juvenile arthritis need to have regular thorough eye exams.

Some children with juvenile arthritis also have growth problems. Depending on the severity of the disease and the joints involved, these may include:

- Bone growth that is too fast or too slow. This change in growth rate can cause one leg or arm to be longer than the other. Other children may have a small or misshapen chin.

- Uneven joint growth.

- Slow overall growth. Doctors are exploring the use of growth hormone to treat this problem.

Juvenile arthritis diagnosis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis may be difficult to diagnose because some children may not complain of pain at first and joint swelling may not be obvious. There is no blood test that can be used to diagnose juvenile arthritis. Adults with rheumatoid arthritis typically have a positive rheumatoid factor blood test, but children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis typically have a negative rheumatoid factor blood test. As a result, diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis depends on physical findings, medical history, and the exclusion of other diagnoses.

Doctors usually suspect arthritis when a child has symptoms of:

- Constant joint pain or swelling.

- Limping.

- Stiffness when awakening.

- Reluctance to use an arm or leg.

- Skin rashes that can’t be explained.

- Persistent fever along with swelling of lymph nodes or inflammation in the body’s organs.

- Reduced activity level

- Difficulty with fine motor activities

Other conditions that can look like juvenile idiopathic arthritis, including infections, childhood cancer, bone disorders, Lyme disease, and lupus also must be ruled out before a diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis can be confirmed.

To be sure that it is juvenile arthritis, doctors may:

- Perform a physical exam.

- Ask about family health history.

- Order lab or blood tests.

- Order x-rays.

Juvenile arthritis treatment

Unfortunately, there is no cure for juvenile arthritis, although with early diagnosis and aggressive treatment, remission is possible. It is important to seek treatment from health care professionals who are knowledgeable about childhood arthritis. The best care for children with juvenile arthritis is provided by a pediatric rheumatology team that has extensive experience and can diagnose and manage the complex needs of the child and family most effectively. The core team may consist of a pediatric rheumatologist, physical and occupational therapist, social worker, and nurse specialist. This core team can coordinate care with a child’s pediatrician, adult rheumatologists, other physicians (such as an ophthalmologist or orthopedic surgeon), and other health professionals (dentist, nutritionist or psychologist) as well as reach out to schools and additional community resources to ensure that the child receives the best care possible.

The overall treatment goal is to control symptoms, prevent joint damage, and maintain function. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often the first type of medication recommended. These are usually ibuprofen or naproxen and are used primarily to reduce inflammation and relieve pain. NSAIDs will help calm down the disease.

When only a few joints are involved, a steroid can be injected into the joint before any additional medications are given. Steroids injected into the joint do not have significant side effects. Oral steroids such as prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, Prelone, Orapred) may be used in certain situations, but only for as short a time and at the lowest dose possible. The long-term use of steroids is associated with side effects such as weight gain, poor growth, osteoporosis, cataracts, avascular necrosis, hypertension, and risk of infection.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are added as a second-line treatment when arthritis involves many joints or does not respond to steroid joint injections. DMARDs include methotrexate (Rheumatrex), leflunamide (Arava), and more recently developed medications known as biologics. The biologics include anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), abatacept (Orencia), anakinra (Kineret;), canakinumab (Ilaris), tocilizumab (Actemra), and rituximab (Rituxan). Each of these medications may cause side effects that need to be monitored and discussed with the pediatric rheumatologist treating your child. Many of these treatments are approved for use in children as well as adults. In addition, researchers are developing new treatments.

Biologic agents are a new class of drugs that also slow or stop the progression of the disease. These are usually only used if the disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) do not seem to work or if the patient has arthritis of the sacroiliac joint.

Splints

In some cases, splints and other devices can help maintain joint alignment. Splinting is useful in children with juvenile arthritis, either at night or during the day, to reduce inflammation and prevent contractures. Splints (braces made of plastic or other materials) are often used in the arm and hand to prevent contractures of the fingers and wrists.

Additional options

In addition to medications, warm baths or an electric blanket may help soothe sore joints.

Exercise is key to reducing symptoms of juvenile arthritis and maintaining range of motion of the joints.

Pain sometimes limits what children with juvenile arthritis can do. However, exercise is key to reducing the symptoms of arthritis and maintaining function and range of motion of the joints. Ask your child’s health care team for exercise guidelines.

Most children with arthritis can take part in physical activities and certain sports when their symptoms are under control. Swimming is a good activity because it uses many joints and muscles without putting weight on the joints.

During a disease flare, your child’s doctor may advise your child to limit certain activities. It will depend on the joints involved. Once the flare is over, your child can return to his or her normal activities.

Surgical treatment

Surgery is not often needed in treating juvenile arthritis. In very severe forms of juvenile arthritis or with very severe complications, surgery may be necessary to improve the position of the joint. An example of this might be when a joint has become deformed.

Joint replacement — frequently used to treat adults with arthritis — has almost no place in treating children.

Living with juvenile arthritis

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis should attend school, participate in extra-curricular and family activities, and live life as normally as possible. To foster a healthy transition to adulthood, adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis should be allowed to enjoy independent activities, such as taking a part-time job and learning to drive.

A positive outlook and continued physical activity will help. Physical and occupational therapy can increase joint motion, reduce pain, improve function, and increase strength and endurance. Therapists may construct splints to prevent permanent joint tightening or deformities, and work with school-based therapists to address issues at school.

Opportunities for the child to interact with other children who have arthritis may be available in or near your community. The rheumatology team may be able to provide information about summer camps and other group activities. The local chapter of the Arthritis Foundation can help connect families and provide support.

Parents should be familiar with Federal Act 504, which may provide children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis special accommodations at school. Families with children with rheumatic diseases may be eligible for assistance through state agencies or services such as vocational rehabilitation. They may also benefit from information and activities available through the Juvenile Arthritis Alliance.

Juvenile arthritis prognosis

For many years it was believed that most children eventually outgrow juvenile arthritis. Now it is known that half of the children diagnosed with juvenile arthritis will continue to have active arthritis 10 years after diagnosis unless they receive aggressive treatment.

Advances in treatment over the last 20 years—especially the introduction of early use of intra-articular steroids, methotrexate, and biologic medications—have dramatically improved the prognosis for children with arthritis. Almost all children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis lead productive lives. However, many patients, particularly those with polyarticular disease, may have problems with active disease throughout adulthood, with sustained remission attained in a minority of patients.

Early hip or wrist involvement, symmetrical disease, the presence of rheumatoid factor, and prolonged active systemic disease have been associated with poor long-term outcomes. Compared with adults with rheumatoid factor-positive rheumatoid arthritis, however, children are at less risk for rheumatoid lung involvement and vasculitis. The anti – cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies antibodies test may be more specific than the rheumatoid factor test, but it is not as well studied in children.

Children with systemic-onset disease tend to either respond completely to medical therapy or develop a severe polyarticular course that tends to be refractory to medical treatment, with disease persisting into adulthood.

Most children with oligoarticular disease demonstrate eventual permanent remission, although a small number progress to persisting polyarticular disease.

Concern has been raised that the use of biologics may increase cancer risk among patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis; however, lack of data on the baseline risk of cancer in this population has made it difficult to determine whether the concern is justified. A review of a large cohort of patients from the Swedish registry found an increased risk of cancer in patients who had not been on biologic therapies and had been diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the last 20 years. However, this risk was not found if the analysis was extended to patients diagnosed between 1969 and 1987 2.

The results of this study were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, they may have implications for interpretation of cancer signals in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, particularly those who are on ongoing therapy with biologic agents, such as TNF-alpha inhibitors.