Paragonimiasis

Paragonimiasis also called lung fluke disease, is caused by infection with a number of species of trematodes (flatworm) belonging to the genus Paragonimus. The most common Paragonimus that infects humans are Paragonimus westermani, Paragonimus heterotremus and Paragonimus philippinensis in Asia (China, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Republic of Korea, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam and other east Asian countries); Paragonimus africanus and Paragonimus uterobilateralis in western and central Africa; Paragonimus caliensis, Paragonimus kellicotti and Paragonimus mexicanus in north, central and south America 1. Adult Paragonimus lung flukes may measure up to 20 mm x 10 mm.

Human paragonimiasis is acquired through ingestion of raw or undercooked crabs or crayfish, and is usually a lung infection2. Less frequent, but more serious cases of paragonimiasis occur when the parasite travels to the central nervous system, where it can cause symptoms of meningitis. After ingestion, metacercariae excyst in the small intestine and release larvae that penetrate the duodenal wall and enter the peritoneal cavity. The larvae migrate for approximately 1 week, then penetrate the diaphragm, enter the pleural cavity, and migrate directly through lung tissue to reach the bronchi. There they form cystic cavities and develop into adult worms in 5-6 weeks. The adult parasites are reddish brown and ovoid, measuring 7.5-12 mm by 4-6 mm. Adult worms induce an inflammatory response in the lungs, generating a fibrous cyst that contains a purulent, bloody effusion and eggs released by the flukes which are passed into the environment via expectoration, or may be swallowed and passed with feces. When deposited in fresh water, eggs hatch to release miracidiae, which then invade specific snail hosts. Thousands of cercariae are later released from the infected snail, which encyst (as metacercariae) in the gills, muscles, legs, and viscera of freshwater crustaceans (crabs or crayfish).

Although rare, paragonimiasis has been acquired in the United States, with multiple cases reported from the Midwest 2. Once the diagnosis is made, effective treatment for paragonimiasis is available from a physician.

Where is Paragonimus lung fluke found?

Paragonimus westermani and several other species are found throughout eastern, southwestern, and southeast Asia including China, the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. Paragonimus africanus is found in Africa, and Paragonimus mexicanus in Central and South America. There are several species of Paragonimus in other parts of the world that can infect humans. Paragonimus kellicotti is found in the midwestern and southern United States living in crayfish. Some human cases of infection have been associated with eating raw crayfish on river raft trips in the Midwest. Paragonimus has caused illness after ingestion of raw freshwater crabs.

Is lung fluke infection contagious?

No. Paragonimus infection is not contagious.

Paragonimiasis causes

Paragonimiasis or lung fluke infection is transmitted by eating infected crab or crawfish that is either, raw, partially cooked, pickled, or salted. The larval stages of the Paragonimus parasite are released when the crab or crawfish is digested. They then migrate within the body, most often ending up in the lungs. In 6-10 weeks the larvae mature into adult flukes.

Several species of Paragonimus cause most infections; the most important is Paragonimus westermani (the oriental lung fluke), which occurs primarily in Asia including China, the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. Paragonimus africanus causes infection in Africa, and Paragonimus mexicanus in Central and South America. Specialty dishes in which shellfish are consumed raw or prepared only in vinegar, brine, or wine without cooking play a key role in the transmission of paragonimiasis. Raw crabs or crayfish are also used in traditional medicine practices in Korea, Japan, and some parts of Africa.

Although rare, human paragonimiasis from Paragonimus kellicotti has been acquired in the United States, with multiple cases from the Midwest. Several cases have been associated with ingestion of uncooked crawfish during river raft float trips in Missouri.

Paragonimiasis life cycle

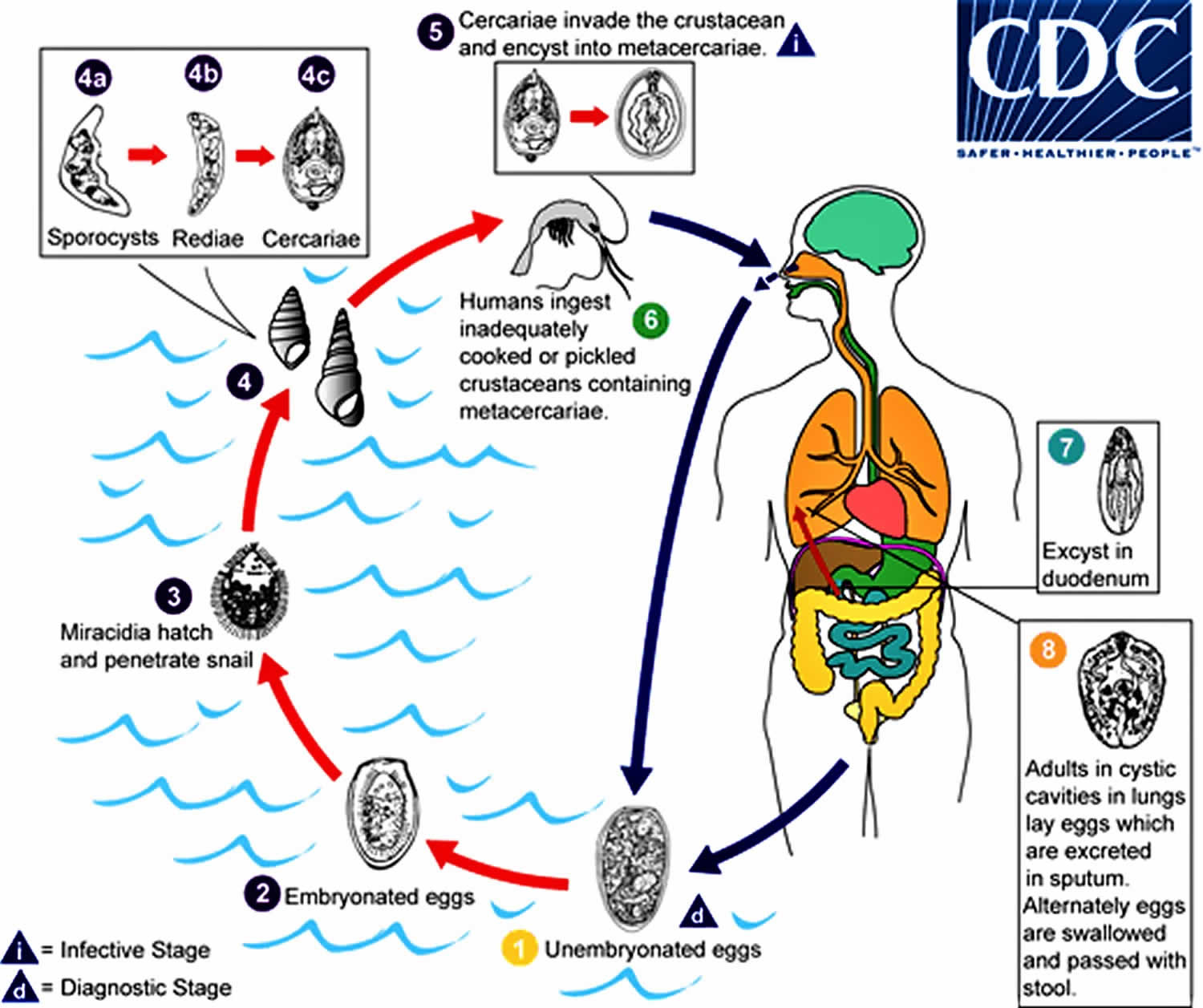

The eggs are excreted unembryonated in the sputum, or alternately they are swallowed and passed with stool (number #1). In the external environment, the eggs become embryonated (number #2), and miracidia hatch and seek the first intermediate host, a snail, and penetrate its soft tissues (number #3). Miracidia go through several developmental stages inside the snail (number #4): sporocysts (number #4a), rediae (number #4b), with the latter giving rise to many cercariae (number #4c), which emerge from the snail. The cercariae invade the second intermediate host, a crustacean such as a crab or crayfish, where they encyst and become metacercariae. This is the infective stage for the mammalian host (number #5). Human infection with Paragonimus westermani occurs by eating inadequately cooked or pickled crab or crayfish that harbor metacercariae of the parasite (number #6). The metacercariae excyst in the duodenum (number #7), penetrate through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity, then through the abdominal wall and diaphragm into the lungs, where they become encapsulated and develop into adults (number #8) (7.5 to 12 mm by 4 to 6 mm). The worms can also reach other organs and tissues, such as the brain and striated muscles, respectively. However, when this takes place completion of the life cycles is not achieved, because the eggs laid cannot exit these sites. Time from infection to oviposition is 65 to 90 days.

Infections may persist for 20 years in humans. Animals such as pigs, dogs, and a variety of feline species can also harbor Paragonimus westermani.

Figure 1. Paragonimiasis life cycle

Paragonimiasis prevention

Never eat raw freshwater crabs or crayfish. Cook crabs and crayfish to at least 145°F (~63°C). Travelers should be advised to avoid traditional meals containing undercooked freshwater crustaceans.

Paragonimiasis symptoms

Adult lung flukes living in the lung cause lung disease. After 2-15 days, the initial signs and symptoms may be diarrhea and abdominal pain. This may be followed several days later by low-grade fever, chest pain, and fatigue. The symptoms may also include a dry cough initially, which later often becomes productive with rusty-colored or blood-tinged sputum on exertion. Persons with light infections may have no symptoms. The symptoms of paragonimiasis can be similar to those of tuberculosis or bronchitis, with coughing up of blood-tinged sputum.

Paragonimiasis diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made by identifying Paragonimus eggs in the sputum or sometimes in the stool (from ingesting eggs after coughing them up, then passing the eggs in the stool). The sputum may be peppered consisting of clumps of eggs produced by the adult fluke living in the lung.

Sputum examined microscopically may reveal Paragonimus eggs released by the flukes in the lungs. Keep in mind that the acid-fast stain that is used for tuberculosis testing of sputum destroys eggs. The eggs may also be found by multiple stool exams on different days as a result of coughed-up eggs that are swallowed. The microscopic eggs are yellowish brown, 80-120 µm long by 45-70 µm wide, thick-shelled, and with an obvious operculum. Serologic tests can be especially useful for early infections (prior to maturation of flukes) or for ectopic infections where eggs are not passed in stool.

Specific and sensitive antibody tests based on Paragonimus westermani antigens are available through Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and serologic tests using a variety of techniques are available through commercial laboratories.

Peripheral eosinophilia is common and can be intense, especially during the early larval migration stages. Many patients have a spectrum of abnormalities on chest radiographs: lobar infiltrates, coin lesions, cavities, calcified nodules, hilar enlargement, pleural thickening and effusions. Ring-shaped opacities of contiguous cavities giving the characteristic appearance of a bunch of grapes are highly suggestive of pulmonary paragonimiasis. Central nervous system disease may provide similar “grapebunch” findings, characteristically seen in the temporal and occipital lobes on computed tomography of the brain. CNS involvement occurs in up to 25% of hospitalized patients and may be associated with Paragonimus-induced meningitis. CNS symptoms may include headaches, seizures, and visual disturbances. Paragonimus flukes may also invade the liver, spleen, intestinal wall, peritoneum, and abdominal lymph nodes.

Ectopic lesions from aberrant migration of flukes can involve any organ, including abdominal viscera, the heart, and the mediastinum. The infection can also affect the liver, spleen, abdomen, and skin. The most clinically recognizable ectopic lesions arise from cerebral paragonimiasis, which, in highly endemic countries, more commonly affects children. These children present with eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, seizures, or signs of space-occupying lesions. Many patients with central nervous system disease also have pulmonary infections. Paragonimus skrjabini often produces skin nodules, subcutaneous abscesses, or a type of creeping eruption known as “trematode larva migrans.”

A tissue biopsy is sometimes performed to look for eggs in a tissue specimen.

Paragonimiasis treatment

Praziquantel is the drug of choice: adult or pediatric dosage, 25 mg/kg given orally three times per day for 2 consecutive days. For cerebral disease, a short course of corticosteroids may be given with the praziquantel to help reduce the inflammatory response around dying flukes.

Alternative: Triclabendazole, adult or pediatric dosage, 10 mg/kg orally once or twice.

Praziquantel

Note on treatment in pregnancy

Pregnancy Category B: Either animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women or animal-reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (and there is no evidence of a risk in later trimesters).

Praziquantel is pregnancy category B. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. However, the available evidence suggests no difference in adverse birth outcomes in the children of women who were accidentally treated with praziquantel during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO encourages the use of praziquantel in any stage of pregnancy. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

Praziquantel is excreted in low concentrations in human milk. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, the use of praziquantel during lactation is encouraged. For individual patients in clinical settings, praziquantel should be used in breast-feeding women only when the risk to the infant is outweighed by the risk of disease progress in the mother in the absence of treatment.

Note on treatment in children

The safety of praziquantel in children aged less than 4 years has not been established. Many children younger than 4 years old have been treated without reported adverse effects in mass prevention campaigns and in studies of schistosomiasis. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment of children younger than 4 years old who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Triclabendazole

Note on treatment in pregnancy

There are no available data on the use of triclabendazole in pregnant women to inform a drug-associated risk for major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

According to the product label (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/208711s000lbl.pdf), there are no data on the presence of triclabendazole in human milk, the effects on the breastfed infant, or the effects on milk production. Published animal data indicate that triclabendazole is detected in goat milk when administered as a single dose to one lactating animal. When a drug is present in animal milk, it is likely that the drug will be present in human milk. The developmental and health benefits of breastfeeding should be considered along with the mother’s clinical need for triclabendazole and any potential adverse effects on the breastfed infant from the medication or from the underlying maternal condition.

Note on treatment in children

According to the product label (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/208711s000lbl.pdf), which addresses treatment of fascioliasis, the safety and effectiveness of triclabendazole have been established for pediatric patients aged 6 years and older (the age group for which the drug has been approved by FDA for treatment of fascioliasis) but have not been established for younger patients.