Jaw claudication

Jaw claudication is pain in the jaw when chewing. Jaw claudication consists in the appearance of pain and fatigue or discomfort of the jaw muscles during chewing of firm foods such as meat, chewing gum, or prolonged speaking 1. Jaw claudication is due ischemia of the internal maxillary artery supplying the masseter muscles and facial artery as well as its branches. Jaw claudication is the most common characteristic of giant cell arteritis, although it is only present in less than half of the cases based on different studies 2. Tongue infarction is almost pathognomonic for giant cell arteritis 3.

Giant cell arteritis is the most common form of vasculitis that occurs in adults. Almost all patients who develop giant cell arteritis are over the age of 50. The average age at onset is 72, and almost all people with the disease are over the age of 50. Women are afflicted with the disease 2 to 3 times more commonly than men. Giant cell arteritis can occur in every racial group but is most common in people of Scandinavian descent.

Giant cell arteritis commonly causes headaches, joint pain, facial pain, fever, and difficulties with vision, and sometimes permanent visual loss in one or both eyes. Because giant cell arteritis is relatively uncommon and because giant cell arteritis can cause so many different symptoms, the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis can be difficult to make. With appropriate therapy, giant cell arteritis is an eminently treatable, controllable, and often curable disease. Giant cell arteritis used to be called “temporal arteritis” because the temporal arteries, which course along the sides of the head just in front of the ears (to the temples) can become inflamed. However, scientists also know that other blood vessels, namely the aorta and its branches, can also become inflammed. The term “giant cell arteritis” is often used because when one looks at biopsies of inflamed temporal arteries under a microscope, one often sees large or “giant” cells.

Jaw claudication causes

Jaw claudication is the most common characteristic of giant cell arteritis. With giant cell arteritis, the lining of arteries becomes inflamed, causing them to swell. This swelling narrows your blood vessels, reducing the amount of blood — and, therefore, oxygen and vital nutrients — that reaches your body’s tissues.

Almost any large or medium-sized artery can be affected, but swelling most often occurs in the arteries in the temples. These are just in front of your ears and continue up into your scalp.

What causes these arteries to become inflamed isn’t known, but it’s thought to involve abnormal attacks on artery walls by the immune system. Certain genes and environmental factors might increase your susceptibility to the condition.

Risk factors of developing giant cell arteritis

Several factors can increase your risk of developing giant cell arteritis, including:

- Age. Giant cell arteritis affects adults only, and rarely those under 50. Most people with this condition develop signs and symptoms between the ages of 70 and 80.

- Sex. Women are about two times more likely to develop the condition than men are.

- Race and geographic region. Giant cell arteritis is most common among white people in Northern European populations or of Scandinavian descent.

- Polymyalgia rheumatica. Having polymyalgia rheumatica puts you at increased risk of developing giant cell arteritis.

- Family history. Sometimes the condition runs in families.

Jaw claudication symptoms

Jaw claudication is pain in the jaw when chewing. Jaw claudication consists in the appearance of pain and fatigue or discomfort of the jaw muscles during chewing of firm foods such as meat, chewing gum, or prolonged speaking. Jaw claudication is highlly predictive of temporal arteritis, and it is a result of ischemia of the maxillary artery supplying the masseter muscles. Temporal headache and jaw claudication may be the key for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis 1.

The most common symptoms of giant cell arteritis are persistent, severe head pain that usually affects both temples, pain in the jaw after chewing (jaw claudication), fever, and blurred vision and pain in the shoulders and hips (called polymyalgia rheumatica). Head pain can progressively worsen, come and go, or subside temporarily.

Other symptoms can include tenderness of scalp (it hurts to comb the hair), cough, throat pain, tongue pain, weight loss, depression, stroke, or pain in the arms during exercise. Some patients have many of these symptoms; others have only a few. Blindness — the most feared complication — can develop if the disease is not treated in a timely fashion.

Signs and symptoms of giant cell arteritis may include 4:

- Non-specific symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and unintended weight loss.

- Headaches, which most often occur over the temples. They may progressively worsen or they may sometimes go away and come back. They may be associated with tenderness of the scalp.

- Jaw pain when you chew or open your mouth wide (jaw claudication).

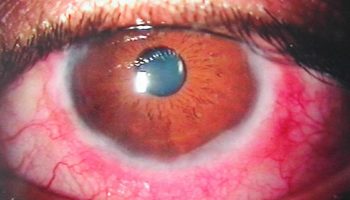

- Vision loss or double vision, particularly in people who also have jaw pain

- Partial or complete permanent vision loss, which is most often sudden and painless. Loss of vision in one or both eyes is reported in 15 to 20 percent of people with giant cell arteritis.

- Polymyalgia rheumatica, a condition that causes muscle pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and hips. This can occur with or without giant cell arteritis but occurs in about 40% to 50% of people with giant cell arteritis.

- Other musculoskeletal symptoms such as pain from inflammation of the tissues that line the joints (synovitis), swelling of the hands and/or feet, and pitting edema (noticeable swelling due to fluid build-up).

- Upper respiratory symptoms, particularly a dry cough.

- Symptoms specific to large vessel giant cell arteritis, which refers to involvement of the aorta and its major proximal branches, especially in the arms. People with large vessel giant cell arteritis are at increased risk for severe complications including aortic aneurysm and dissection.

- Central nervous system manifestations such as stroke (which is uncommon), and rarely, peripheral neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, myelopathy, dementia, or other symptoms.

If you develop a new, persistent headache or any of the signs and symptoms listed above, see your doctor without delay. If you’re diagnosed with giant cell arteritis, starting treatment as soon as possible can usually help prevent vision loss.

Jaw claudication complications

Giant cell arteritis can cause serious complications, including:

- Blindness. Diminished blood flow to your eyes can cause sudden, painless vision loss in one or, rarely, both eyes. Loss of vision is usually permanent.

- Aortic aneurysm. An aneurysm is a bulge that forms in a weakened blood vessel, usually in the large artery that runs down the center of your chest and abdomen (aorta). An aortic aneurysm might burst, causing life-threatening internal bleeding. Because this complication can occur even years after the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis, your doctor might monitor your aorta with annual chest X-rays or other imaging tests, such as ultrasound and CT.

- Stroke. This is an uncommon complication of giant cell arteritis.

Jaw claudication diagnosis

Giant cell arteritis can be difficult to diagnose because its early symptoms resemble those of other common conditions. For this reason, your doctor will try to rule out other possible causes of your problem.

In addition to asking about your symptoms and medical history, your doctor is likely to perform a thorough physical exam, paying particular attention to your temporal arteries. Often, one or both of these arteries are tender, with a reduced pulse and a hard, cordlike feel and appearance.

Your doctor might also recommend certain tests.

Blood tests

The following tests might be used to help diagnose your condition and to follow your progress during treatment.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Commonly referred to as the sed rate, this test measures how quickly red blood cells fall to the bottom of a tube of blood. Red cells that drop rapidly might indicate inflammation in your body.

- C-reactive protein (CRP). This measures a substance your liver produces when inflammation is present.

Imaging tests

These might be used to diagnose giant cell arteritis and to monitor your response to treatment. Tests might include:

- Doppler ultrasound. This test uses sound waves to produce images of blood flowing through your blood vessels.

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). This test combines an MRI with the use of a contrast material that produces detailed images of your blood vessels. Let your doctor know ahead of time if you’re uncomfortable being confined in a small space because the test is conducted in a tube-shaped machine.

- Positron emission tomography (PET). If your doctor suspects you might have giant cell arteritis in large arteries, such as your aorta, he or she might recommend PET. This test uses an intravenous tracer solution that contains a tiny amount of radioactive material. A PET scan can produce detailed images of your larger blood vessels and highlight areas of inflammation.

Biopsy

The best way to confirm a diagnosis of giant cell arteritis is by taking a small sample (biopsy) of the temporal artery. This artery is situated close to the skin just in front of your ears and continues up to your scalp. The procedure is performed on an outpatient basis using local anesthesia, usually with little discomfort or scarring. The sample is examined under a microscope in a laboratory.

If you have giant cell arteritis, the artery will often show inflammation that includes abnormally large cells, called giant cells, which give the disease its name. It’s possible to have giant cell arteritis and have a negative biopsy result.

If the results aren’t clear, your doctor might advise another temporal artery biopsy on the other side of your head.

Temporal artery biopsy is the current gold standard test for establishing the giant cell arteritis diagnosis, with a high specificity but low sensitivity. It can be misleading in a significant number of cases. Up to 44% of patients with clinical features of giant cell arteritis have a negative biopsy 5. There are many reasons for this, including the adequacy of the specimen obtained, the duration of glucocorticoid treatment prior to biopsy and the presence of skip lesions (intermittent). However, it is also important to avoid treating those without the condition, because there is a very high incidence of side effects associated with long-term glucocorticoid therapy. Ultrasound and other imaging techniques are emerging as alternative tests to biopsy but have not been widely accepted.

Recent literature suggests that there is now enough evidence that temporal artery biopsy does not change the management of giant cell arteritis and that the use of imaging modalities, such as ultrasound scan, color doppler sonography and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be sufficient to confirm the diagnosis. Gallium-67 SPECT scintigraphy may be useful in the diagnosis of the disease too, although further studies are needed to confirm this data 1.

Jaw claudication treatment

The main treatment for giant cell arteritis consists of high doses of a corticosteroid drug such as prednisone. Because immediate treatment is necessary to prevent vision loss, your doctor is likely to start medication even before confirming the diagnosis with a biopsy.

You’ll likely begin to feel better within a few days of beginning treatment. If you have visual loss before starting treatment with corticosteroids, it’s unlikely that your vision will improve. However, your unaffected eye might be able to compensate for some of the visual changes.

You may need to continue taking medication for one to two years or longer. After the first month, your doctor might gradually begin to lower the dosage until you reach the lowest dose of corticosteroids needed to control inflammation.

Some symptoms, particularly headaches, may return during this tapering period. This is the point at which many people also develop symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica. Such flares can usually be treated with slight increases in the corticosteroid dose. Your doctor might also suggest an immune-suppressing drug called methotrexate (Trexall).

Corticosteroids can lead to serious side effects, such as osteoporosis, high blood pressure and muscle weakness. To counter potential side effects, your doctor is likely to monitor your bone density and might prescribe calcium and vitamin D supplements or other medications to help prevent bone loss.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved tocilizumab (Actemra) to treat giant cell arteritis. It’s given as an injection under your skin. Side effects include making you more prone to infections. More research is needed.

- Peral-Cagigal B, Pérez-Villar Á, Redondo-González LM, et al. Temporal headache and jaw claudication may be the key for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018;23(3):e290–e294. Published 2018 May 1. doi:10.4317/medoral.22298 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5945239[↩][↩][↩]

- Armona J, Rodríguez-Valverde V, González-Gay MA, Figueroa M, Fernández-Sueiro JL, González Vela C. Giant cell arteritis. A study of 191 patients. Med Clin. 1995;105:734–737.[↩]

- Bhatti MT, Frohman L, Nesher G. MD Roundtable: Diagnosing Giant Cell Arteritis. EyeNet. 2017 June. 21(6):31-34.[↩]

- Clinical manifestations of giant cell arteritis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-of-giant-cell-arteritis[↩]

- Luqmani R, Lee E, Singh S, Gillet M, Schmidt WA, Bradburn M. The role of ultrasound compared to biopsy of temporal arteries in the diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis (TABUL): a diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness study. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20:1–23.[↩]