Genu valgum

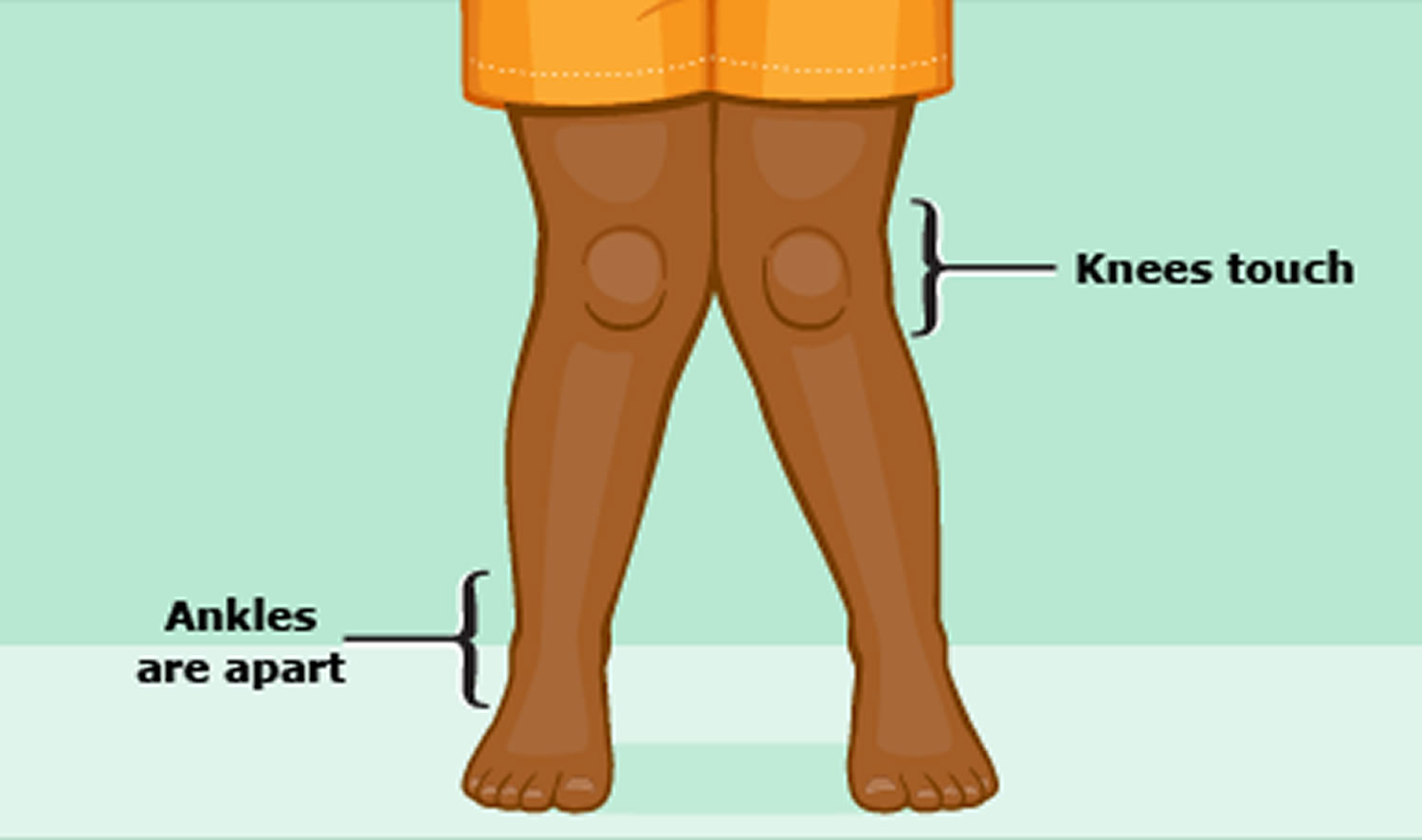

Genu valgum commonly called “knock-knees” or valgus knee, is a condition where the knees angle in and touch one another when the legs are straightened 1. Genu valgum or knock knees are condition in which the knees touch, but the ankles do not touch. The legs turn inward. Individuals with severe genu valgum deformities are typically unable to touch their feet together while simultaneously straightening the legs. See your child’s doctor if you think your child has genu valgum or knock knees.

Genu valgum is a common condition in children and is almost always a normal part of a child’s development 2. Because of the way their bodies are positioned in the uterus, most babies are born bowlegged (genu varum) where the legs curve outward at the knees while the feet and ankles touch and stay that way until about age 2 or 3. After that, their legs turn inward and take on a knock-kneed or genu valgum appearance until they’re about 7 or 8 years old. At that time, the legs generally assume their normal alignment 3. In rare cases, genu valgum that develops later at around age 6 can be a sign of an underlying bone disease.

Treatment for genu valgum is almost never required as the legs usually straighten out on their own. Severe genu valgum or knock-knees that are more pronounced on one side sometimes require treatment with braces that straighten the legs. Surgery to correct genu valgum is usually only done if the condition is severe and causes pain or difficulty walking.

For persistent genu valgum, treatment recommendations have included a wide array of options, ranging from lifestyle restriction and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to bracing, exercise programs, and physical therapy 4. In recalcitrant cases, surgery may be advised. No consensus exists regarding the optimal treatment. Some surgeons focus (perhaps inappropriately) on the patella itself, favoring arthroscopic or open realignment techniques. However, if valgus malalignment of the extremity is significant, corrective osteotomy or, in the skeletally immature patient, hemiepiphysiodesis may be indicated.

Osteotomy indications and techniques have been well described in standard textbooks and orthopedic journals and are not the focus of this article. Hemiepiphysiodesis can be accomplished by using the classic Phemister bone block technique, the percutaneous method, hemiphyseal stapling, or the application of a single two-hole plate and screws around the physis. The senior author, having experience in each of these techniques, developed the last of these techniques in order to solve two of the problems sometimes encountered with staples—namely, hardware fatigue and migration.

Figure 1. Genu valgum knee

Genu valgum causes

Infants start out with bowlegs (genu varum) where the legs curve outward at the knees while the feet and ankles touch because of their folded position while in their mother’s womb. The legs begin to straighten once the child starts to walk (at about 12 to 18 months). By age 3, the child becomes knock-kneed or genu valgum. When the child stands, the knees touch but the ankles are apart.

By puberty, the legs straighten out and most children can stand with the knees and ankles touching (without forcing the position).

Genu valgum (knock knees) can also develop as a result of a medical problem or disease, such as:

- Injury of the shinbone (only one leg will be knock-kneed)

- Osteomyelitis (bone infection)

- Overweight or obesity

- Rickets (a disease caused by a lack of vitamin D)

- Cerebral palsy

- Spina bifida.

In children aging 2 to 6 years, valgus knee is normal within certain limits of knee angle, therefore being characterized as physiological 5. Most children with genu valgum at these ages have spontaneous correction 6. Angle and type of deviation can be either normal or physiological, depending on the age 7. Newborns are usually defined as physiological and, around 18 to 24 months, their tibiofemoral angle variation aligns to zero degree. At 3 years, the maximum deviation value in children with normal development reaches 12 degrees and decreases until it stabilizes at 5 to 6 degrees by 6 or 7 years of age 7. Intermalleolar distance measured with a ruler, being the child in orthostatic position, is one of the clinical alternatives to measure valgus deformity 8. Children under 7 years presenting physiological valgus knee have intermalleolar distance of up to 8 cm, the greatest distance being observed between 3 and 4 years 9.

The prevalence of obesity is known to have been increasing over the last decades. According to Calvete 10, obesity causes mechanical overload to the locomotor system, postural misalignment with anteriority of mass center, thus leading to feet functional alterations and an increase in mechanical needs to adapt to the new body scheme. The action of body weight on the feet makes the medial longitudinal arch tend to fall, assuming a pronated or valgus foot posture. In order to compensate, the tibia happens to rotate internally and, consequently, there is knee compression, pain and medial compartment wear, as well as an internal rotation of the hip, which contributes to a greater vector in genu valgum and misalignment of the extensor system 11.

The association between obesity and genu valgum is explained by a sum of factors. Wearing et al. 12 reported that bone tissues remodel according to load exerted on it and, in childhood, they have a greater amount of collagen, therefore being more flexible, more tolerant to plastic deformation, and less resistant to compression. Thus, when overload is increased as it happens with obese individuals, those who are in growth phase are more susceptible to deformities 13.

Bruschini and Nery 14 explain this by indicating that the presence of abdominal protrusion in the obese causes the center of gravity to move anteriorly, leading the vertebral column and the lower limbs to adjust, with pelvic anteversion associated with internal rotation of the hips. All this, along with fat accumulation at the thigh region, causes the malleolus to move away, promoting medial half opening and hyper pressure to the lateral half of the knee. Over time and development, uneven growth occurs between both parts and the deformity installs permanently.

Genu valgum prevention

There is no known prevention for normal genu valgum or knock knees.

Genu valgum symptoms

If someone with genu valgum stands with their knees together, their lower legs will be spread out so their feet and ankles are further apart than normal.

A small distance between the ankles is normal, but in people with genu valgum this gap can be up to 8cm (just over 3 inches) or more.

Knock knees don’t usually cause any other problems, although a few severe cases may cause knee pain, a limp or difficulty walking.

Knock knees that don’t improve on their own can also place your knees under extra pressure, which may increase your risk of developing arthritis.

Genu valgum possible complications

Genu valgum complications may include:

- Difficulty walking (very rare)

- Self-esteem changes related to cosmetic appearance of knock knees

- If left untreated, knock knees can lead to early arthritis of the knee.

Genu valgum diagnosis

Medical history

It is important to identify and document the natural history of genu valgum. On rare occasions, genu valgum may be noted in the nursery, indicating the presence of some type of localized or generalized skeletal malformation or dysplasia. Congenital lateral dislocation of the patella has been described. The extensor mechanism of the knee is displaced laterally so that every time the child contracts the quadriceps, the knee is flexed (rather than extended) and rotates outward, accentuating the valgus deformity. Another example is postaxial hypoplasia of the limb, sometimes first manifested by the absence of a lateral ray (or two rays) of the foot 15.

More commonly, genu valgum does not become apparent until after the child reaches walking age. A normal variant of the disorder in toddlers (physiologic valgus) typically is symmetrical and pain-free, but it should resolve spontaneously by the time the child is aged 6 years. If the valgus is unilateral or symptomatic, referral to an orthopedist and radiographic evaluation are warranted.

Family history may be important because certain heritable conditions, such as hereditary multiple exostoses, Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, or vitamin D–resistant rickets may predispose a patient to this condition.

Physical examination

The physical examination should include assessment of the gait pattern, including the propensity for circumduction, and evaluation of lower-extremity lengths. Stature, craniofacial features, the spine, and the upper extremities should be evaluated. Various genetic conditions and skeletal dysplasias may be documented in this manner; consultation with a geneticist may be warranted.

With the child standing, compare the relative limb lengths by leveling the pelvis with blocks and measuring and recording the intermalleolar distance (IMD). Torsional deformities of the femur, tibia, or both should be documented. Often, genu valgum is observed in association with outward torsion of the femur, the tibia, or both. Look for retropatellar crepitus and tenderness and note patellar tilt, tracking, and stability. For situations other than the aforementioned physiologic genu valgum, medical imaging is warranted.

Imaging studies

The radiographic parameters relevant to defining genu valgum are best measured on a full-length standing anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the legs 4. The angle is measured between the femoral shaft and its condyles (normal angle, 84°); this is referred to as the lateral distal femoral angle. The other relevant angle is the proximal medial tibial angle; this is the angle between the tibial shaft and its plateaus (normal angle, 87°).

The mechanical axis (center of gravity) is a straight line drawn from the center of the femoral head to the center of the ankle; this should bisect the knee. Allowing for variations of normal, an axis within the two central quadrants (zones +1 or –1) of the knee is deemed acceptable.

With normal alignment, the lower-extremity lengths are equal, and the mechanical axis bisects the knee when the patient is standing erect with the patellae facing forward. This position places relatively balanced forces on the medial and lateral compartments of the knee and on the collateral ligaments, while the patella remains stable and centered in the femoral sulcus.

Genu valgum treatment

In just about every case, genu valgum is a harmless condition that will eventually clear up on its own. When treatment is necessary, the results usually are very good and the condition is corrected with no long-term issues to worry about.

Genu valgum (knock knees) are not treated in most cases.

If the problem continues after age 7, the child may use a night brace. This brace is attached to a shoe.

Surgery may be considered for knock knees that are severe and continue beyond late childhood.

Genu valgum surgery

Children with severe or worsening pathological genu valgum might need orthopaedic surgery to correct their knee alignment, particularly in the presence of persistent pain or disability, regardless of the underlying cause.

There are many operations for pathological genu valgum, surgical options include osteotomy or growth manipulation (hemiepiphysiodesis). A hemiepiphysiodesis is a type of “guided growth” operation involving the placement of staples or a plate on the inside part of the knee to slow down growth while the outside part of the knee continues to grow. This then corrects the knee angle to a straighter position. A study reporting outcomes two years after this operation showed correction in 34 of 38 genu valgum.

Another surgical procedure for pathological genu valgum is a wedge osteotomy, where the top of the shin bone or bottom of the thigh bone is cut and a small portion removed to correct the knee alignment. In a study of 23 adolescents and adults with painful arthritic genu valgum, a wedge osteotomy was found to show improvements in walking ability and alignment after two years.

Orthopaedic surgery is rarely needed. For most kids, genu valgum are just a normal part of growing up.

Stapling has waned in popularity since its introduction, having been supplanted by the tension band plate concept 16. Reference works typically dismiss it as a historical procedure, citing unpredictability and the fear of permanent physeal arrest as results of stapling. Although stapling can work well, occasional breakage or migration of staples can necessitate revision of hardware or premature abandonment of this method of treatment.

Some surgeons have reverted to osteotomy of the femur and/or tibia-fibula as the definitive means of addressing genu valgum 16. However, this is a very invasive method fraught with potential complications, including malunion, delayed healing, infection, neurovascular compromise, and compartment syndrome. Further complicating the picture, these deformities are often bilateral, requiring a staged correction. The aggregate hospitalization, recovery time, costs, and risks make osteotomy a last resort for angular corrections (unless the physis has already closed).

Percutaneous drilling or curettage of a portion of the physis yields only a small scar and no implant is required. However, this is a permanent, irreversible technique. Therefore, its use is necessarily restricted to adolescent patients and is predicated upon precise timing of intervention, requiring close follow-up to avoid undercorrection or (worse yet) overcorrection.

Some authorities advocate using percutaneous epiphyseal transcutaneous screws as a means of achieving angular correction 17. Although this is performed through a small incision, the physis is violated, and the potential exists for the formation of an unwanted physeal bar, with its sequelae. To date, the potential for reversing the procedure has not been documented in younger children; therefore, the only reported cases have been in adolescents.

By comparison, guided growth, using a nonlocking two-hole plate and screws, is a reversible and minimally invasive outpatient procedure, allowing multiple and bilateral simultaneous deformity correction. A single implant is used per physis (see the images below); this serves as a tension band, allowing gradual correction with growth. Because the focal hinge of correction (CORA) is at or near the level of deformity, compensatory and unnecessary translational deformities are avoided 18.

The previous empirical constraints related to the indications for instrumented hemiepiphysiodesis, including appropriate age group and the etiology of deformity, have been challenged successfully with this technique, and results have been consistently good. During the past decade, in a personal series of more than 1000 patients ranging in age from 19 months to 18 years, some of whom had pan-genu deformities, the senior author has not had a permanent physeal closure, nor have any been reported in the literature.

Guided growth has emerged as the treatment of choice in the growing child; osteotomy should be reserved as a salvage option (or for mature patients). Despite the age of the child or the etiology of the valgus, even children with “sick physes” may be well served by the application of an extraperiosteal two-hole plate at the apex (or apices) of the deformity. The ensuing growth should correct the deformity within an average of 12 months. This is documented with quarterly follow-up evaluations, including full-length radiographs with the legs straight.

When the mechanical axis has been restored to neutral, the implants are removed. Growth should be monitored because if the valgus recurs, guided growth may have to be repeated. The goal is to correct the deformity, which alleviates the pain and gait disturbance and protects the knee throughout the growing years. If this requires repeated, yet minor, intervention, the benefits still outweigh the cost and risks of (sometimes) repeated osteotomies. If recurrence is anticipated, an option is to remove the metaphyseal screw percutaneously, monitor subsequent growth, and insert another screw as needed.

Genu valgum prognosis

Children normally outgrow genu valgum (knock knees) without treatment, unless it is caused by a disease.

If surgery is needed, the results are most often good provided that the appropriate criteria (ie, sufficient growth remaining, careful analysis and preoperative planning, proper plate insertion, periodic follow-up) are met, the results of guided growth are uniformly gratifying. The parents and the surgeon must be patient, however, because growth is a slow process. The immediate satisfaction (carpentry) of osteotomies is supplanted by delayed gratification (gardening). The success of this technique is predicated on skillful harnessing of the inherent power of the growth plate. Even a sick physis can respond, given enough time; this is why the procedure works even in patients with skeletal dysplasias and vitamin D–resistant rickets 19.

That patient and family satisfaction are excellent is not surprising, given that guided growth, compared with osteotomy, is less invasive, relatively painless, more cost-effective, and less risky. Down time is minimal, and educational and recreational activities are only temporarily interrupted. Consequently, previous arbitrary guidelines pertaining to minimum age and diagnoses have been abandoned. In the author’s opinion, guided growth with a tension band has become the treatment of choice for most angular deformities of the knee. Osteotomy can still be performed if guided growth is unsuccessful (or vice versa).

Wiemann et al 20 compared the use of the eight-plate for hemiepiphysiodesis (n = 24) with physeal stapling (n = 39) in 63 cases of angular deformity in lower extremities. The eight-plate was as effective as staple hemiepiphysiodesis in terms of correction rate (~10º/year) and complication rate (12.8% vs 12.5%). However, patients with abnormal physes (eg, Blount disease, skeletal dysplasias) did have a higher rate of complications than those with normal physes (27.8% vs 6.7%), though there was no difference between the eight-plate group and the staple group. Stevens and Novais have not shared this experience; the complication rate is exceedingly low in both groups 21.

After analyzing 35 patients, Jelinek et al reported that a shorter operating time for implantation and explantation was noted for the eight-plate technique than for Blount stapling 22.

Vaishya et al 23 retrospectively studied 24 pediatric patients with bilateral (n = 11) or unilateral (n = 13) genu valgum deformity (35 knees) that required surgical correction in an attempt to evaluate the efficacy, correction rate, and complication rate associated with the use of the eight-plate in this setting. Excellent results were achieved in 91.6% of patients. There was one case (4.16%) of partial correction and one case (4.16%) of superficial infection, which was taken care of. There were two cases (8.33%) of overcorrection, which was gradually self-corrected during follow-up.

- Santili C, Faria AP, Alcântara T. Pardine Souza G, Cunha LA. Clínica Ortopédica: Defeitos Congênitos nos Membros Inferiores. 4. Rio de Janeiro: MEDSI; 2003. Deformidades angulares dos joelhos: genuvaro, genuvalgo e joelho recurvado; pp. 609–617[↩]

- Navarro RD. Bruschini S. Ortopedia pediátrica. 2. São Paulo: Atheneu; 1998. Joelhos Valgos; pp. 225–228[↩]

- Range of variation of genu valgum and association with anthropometric characteristics and physical activity: comparison between children aged 3-9 years. Kaspiris A, Zaphiropoulou C, Vasiliadis E. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2013 Jul; 22(4):296-305.[↩]

- Pediatric Genu Valgum. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1259772-overview[↩][↩]

- Navarro RD. Bruschini S. Ortopedia pediátrica. 2. São Paulo: Atheneu; 1998. Joelhos Valgos; pp. 225–228.[↩]

- Kaspiris A, Zaphiropoulou C, Vasiliadis E. Range of variation of genu valgum and association with anthropometric characteristics and physical activity: comparison between children aged 3-9 years. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2013;22:296–305[↩]

- Salenius P, Vankka E. The development of the tibiofemoral angle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:259–261.[↩][↩]

- Lin CJ, Lin SC, Huang W, Ho CS, Chou YL. Physiological knock-knee in preschool children: prevalence, correlating factors, gait analysis, and clinical significance. J Pediatr Orthop. 1999;19:650–654.[↩]

- Heath CH, Staheli LT. Normal limits of knee angle in white children – genu varum and genu varum. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:259–262.[↩]

- Calvete SA. Relationships between postural alterations and sports injuries in obese children and adolescents. Motriz. 2004;10:67–72.[↩]

- Prentice WE, Voight ML. Técnicas em reabilitação musculoesquelética. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2003.[↩]

- Wearing SC, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR, Hills AP. Musculoskeletal disorders associated with obesity: a biomechanical perspective. Obes Rev. 2006;7:239–250.[↩]

- Landauer F, Huber G, Paulmichl K, O’Malley G, Mangge H, Weghuber D. Timely diagnosis of malalignment of the distal extremities is crucial in morbidly obese juveniles. Obes Facts. 2013;6:542–551.[↩]

- Bruschini S, Nery CA. Fisberg M. Obesidade na infância e adolescência. São Paulo: Fundo Editorial Byk; 1995. Aspectos Ortopédicos da Obesidade na Infância e Adolescência; pp. 105–125.[↩]

- Stevens PM, Arms D. Postaxial hypoplasia of the lower extremity. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000 Mar-Apr. 20 (2):166-72.[↩]

- Pediatric Genu Valgum Treatment & Management. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1259772-treatment[↩][↩]

- De Brauwer V, Moens P. Temporary hemiepiphysiodesis for idiopathic genua valga in adolescents: percutaneous transphyseal screws (PETS) versus stapling. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008 Jul-Aug. 28 (5):549-54.[↩]

- Burghardt RD, Herzenberg JE, Standard SC, Paley D. Temporary hemiepiphyseal arrest using a screw and plate device to treat knee and ankle deformities in children: a preliminary report. J Child Orthop. 2008 Jun. 2 (3):187-97.[↩]

- Stevens PM, Klatt JB. Guided growth for pathological physes: radiographic improvement during realignment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008 Sep. 28 (6):632-9.[↩]

- Wiemann JM 4th, Tryon C, Szalay EA. Physeal stapling versus 8-plate hemiepiphysiodesis for guided correction of angular deformity about the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009 Jul-Aug. 29 (5):481-5.[↩]

- Stevens PM, Novais EN. Multilevel guided growth for hip and knee varus secondary to chondrodysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012 Sep. 32 (6):626-30.[↩]

- Jelinek EM, Bittersohl B, Martiny F, Scharfstädt A, Krauspe R, Westhoff B. The 8-plate versus physeal stapling for temporary hemiepiphyseodesis correcting genu valgum and genu varum: a retrospective analysis of thirty five patients. Int Orthop. 2012 Mar. 36 (3):599-605.[↩]

- Vaishya R, Shah M, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. Growth modulation by hemi epiphysiodesis using eight-plate in Genu valgum in Paediatric population. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018 Oct-Dec. 9 (4):327-333.[↩]