Persistent genital arousal disorder

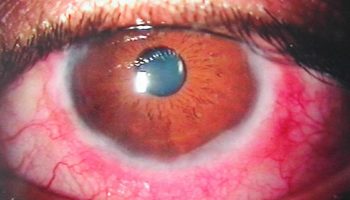

Persistent genital arousal disorder or PGAD was previously called persistent sexual arousal syndrome or restless genital syndrome, is a phenomenon relating mainly to women sexual health, in which afflicted women complain of sudden and frequent unwanted genital arousal that are qualitatively different from the kind of sexual arousal that is associated with sexual desire or subjective arousal 1. Masturbation and orgasms offer little or no relief. Persistent genital arousal disorder prevalence is estimated to approach 1% of young women 2. Only two persistent genital arousal disorder cases have been reported in males associated with restless leg syndrome 2. Although mainly described in women, a variety of PGAD called priapism does occur in men. The syndrome of priapism (similar to PGAD) is a diagnosable medical condition by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition 3. These men have persistent and painful erection of the penis 4.

PGAD remains a poorly understood condition. Women with this condition may suffer substantial distress. It is important to raise awareness of this disabling but treatable condition, to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate investigation and treatment.

It is important not to confuse persistent sexual arousal syndrome with hypersexuality. Hypersexuality manifests as excessive desire and compulsive sexual behavior with or without persistent genital arousal, sometimes referred to as Don Juanism or nymphomania 5. The key difference between the two is that persistent sexual arousal disorder manifests as persistent genital arousal in the absence of sexual desire 6. PGAD is a very rare condition, and it is possible that the sufferers do not report the condition because of shame and embarrassment 1.

Persistent genital arousal disorder or PGAD was documented by Leiblum and Nathan in 2001 7 and only recently characterized as a distinct syndrome 8.

For a diagnosis of PGAD to be made Goldmeier et al. 9 suggested that the following will be present:

- The physiological responses characteristic of sexual arousal (genital vasocongestion [fullness/swelling] and sensitivity with or without nipple fullness/swelling) persist for an extended period of time (hours to days) and do not subside completely on their own;

- The genital arousal does not resolve completely despite one or more orgasms and may require multiple orgasms over hours or days to remit;

- Symptoms of arousal that are usually experienced as unrelated to any subjective sense of sexual excitement or desire;

- The persistent genital arousal may be triggered not only by sexual activity but by nonsexual stimuli as well (e.g., vibrations from a car) or by no apparent stimulus at all; and most importantly,

- The persistent genital arousal is experienced as unbidden, intrusive, and unwanted

- There is at least a moderate or greater feeling of distress associated with the experience 10.

The unremitting nature of the symptoms, predisposes them to become severely depressed and even suicidal 11.

Although many etiologic hypotheses have been proposed, the cause or causes of PGAD remain unknown. PGAD is likely not attributable to a single cause or biopsychosocial factor, and there may be subgroups of women with PGAD who develop the condition through a combination of factors 12. These hypothesized causes include central and peripheral dysregulation, vascular changes, meningeal cysts (most commonly, Tarlov cysts), and pharmacologic and psychologic explanations 13. Central neurological changes (e.g., postinjury, specific brain lesion/anomaly) peripheral neurological changes (e.g., pelvic nerve hypersensitivity or entrapment), vascular changes (e.g., pelvic congestion), mechanical pressure against genital structures, medication-induced changes, psychological changes (stress), initiation or cessation of treatment with antidepressant medication and other mood stabilizers, onset of menopause, physical inactivity, association with an overactive bladder have been implicated as being causal of PGAD 14. One theory suggests that these women may be more vigilant in monitoring small changes in their physical well-being 15.

Evaluating psychological predictors of distress showed that conservative attitudes about sexuality could be expected to characterize women reporting high distress versus low distress, acting as a differentiator factor. It was speculated that women with low openness would possibly endorse a dogmatic and conservative thinking style regarding sexuality and that openness would affect the distress to the genital symptoms through a cognitive path rather than a psychopathological path 16.

Since the cause of PGAD is variable, treatment targeted at the specific cause varies on a case-by-case basis.

Simple treatments include avoiding tight clothing, prolonged sitting or cycling. Masturbation and repeated orgasm can reduce symptoms in some women, but not others. Pelvic physiotherapy to reduce the tension in overactive pelvic muscles is helpful if pelvic muscles are tight and painful. Relaxation techniques, such as regular mindfulness meditation, reduce anxiety and improve brain function.

If your symptoms of PGAD are still distressing, then it is important to discuss these with your doctor. PGAD is rare and very few doctors have experience in the management of this condition. If you believe you have PGAD, then you may wish to print this page and take it with you to your doctor. It’s recommended that your doctor do a full clinical assessment, including asking about your medical history, medications, gynecological history, bladder function and any life stresses or anxiety issues that may be contributing to your pain; do a full gynecological examination, including assessment of the pelvic floor muscles (which may be tight), and location of any sensitive areas – consider whether a pelvic ultrasound (to assess the pelvic organs) or MRI scan (to assess the Pudendal Nerve and Lumbosacral spine) should be done; discuss whether review with a Sexual Trauma Therapist might assist you; consider the use of a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machine for your pain 17.

Several different medications have been tried for PGAD. None suit every woman with this condition, so it may be necessary for you to try a few medications to find one that suits you. Medications that have been used for this condition include: Medications to reduce anxiety – these include benzodiazepines (clonazepam or oxazepam), tricyclic anti-depressants (amitriptyline or nortriptyline), serotonin medications such as duloxetine. Some women find that their PGAD symptoms begin after these medication are ceased Medications that affect dopamine in the brain – these include varenicline (used to stop smoking) or risperidone; Medications for Restless Legs Syndrome, such as pramipexole– Medications for nerve pain such as gabapentin or pregabalin.

PGAD causes

No clear consensus has been reached as to the cause of PGAD. A number of studies have shown that women with PGAD have a higher incidence of neurophysiological disorders such as depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and obsessive compulsive symptoms when compared to non-PGAD women suggesting that there is some psychological basis to the disease 18, 19, 20. Several studies and case reports have also linked PGAD to antidepressant usage, some having onset of symptoms at the initiation of treatment and some on abruptly stopping antidepressants 21. Other observed associations and theories on the cause of persistent genital arousal disorder include increased soy intake 22, exogenous medication 23, Tarlov cysts 24, vascular, peripheral, and central neurologic causes, a history of sexual abuse, overactive bladder and restless leg syndrome, although most cases are considered to be idiopathic (no cause is found). A recent review on the subject by Facelle et al. 25 covers the potential etiology in great depth.

The new study confirms that PGAD can be caused by various conditions affecting the nerves carrying sensation from the genitals. Most common in the study groups: Tarlov cysts, growths on the nerve roots near the bottom of the spine, long considered to have no symptoms. Of the 10 women studied, four had Tarlov cysts. For one, removing it ended her PGAD, confirming that pressure on the nerve roots caused her disorder; but another got no relief from surgery. Other conditions that damage lower spinal nerves, from herniated disks to, in the case of one woman, a mild form of spina bifida, can also cause PGAD, according to the study. Vulvodynia, or chronic pain in the vulva, can be caused by the same lesion that causes PGAD.

Other research suggests that PGAD can also be caused by skin infections, irritation in the genital area, or thinning of the skin due to reduced estrogen after menopause, according to Barry Komisaruk, PhD, a distinguished professor of psychology at Rutgers University–Newark, NJ, who studies the condition. Epileptic seizures and scar tissue from a trauma that puts pressure on the spinal nerves or stretches them can also be a cause.

Little is known about the frequency of occurrence or the validity of each hypothesized cause because the majority of this work is in the form of individual case reports; in most cases, assessments (eg, physical, neurologic, cardiovascular, endocrine) yielded no abnormal findings.

PGAD symptoms

Many women find it hard to describe the sensation, but they do agree that it is unpleasant. Typical words used describe PGAD as a congested, swelling, tingling, wet, throbbing, itching, numb, burning, vibrating or restless feeling in the clitoris, vagina, labia, pelvis, or upper legs. Around 1 in 3 women find this sensation physically painful.

Common triggers include physical stimulation (intercourse or masturbation), psychological stress or anxiety, genital pressure (sitting on hard surfaces or cycling), vibrations from a motor vehicle or erotic visual stimulation. Some women report worsening of the symptoms at night, when blood flow to the vagina increases.

Many women try many things to relieve the unwelcome feeling. Masturbation, orgasm, distraction, intercourse, exercise or a cold compress may help but unfortunately relief of the condition is often only brief or partial. The increased sexual arousal in PGAD does not mean that these women have increased desire for sexual activity. Often satisfaction with sexual activity is lower than in other women.

PGAD is not the same as conditions like nymphomania or satyriasis where there is an increased sexual desire or hypersexuality. PGAD is often associated with a lower satisfaction with sexual activity, and significant distress. The sensations are unwelcome.

PGAD diagnosis

For a diagnosis of PGAD to be made Goldmeier et al. 9 suggested that the following will be present:

- The physiological responses characteristic of sexual arousal (genital vasocongestion [fullness/swelling] and sensitivity with or without nipple fullness/swelling) persist for an extended period of time (hours to days) and do not subside completely on their own;

- The genital arousal does not resolve completely despite one or more orgasms and may require multiple orgasms over hours or days to remit;

- Symptoms of arousal that are usually experienced as unrelated to any subjective sense of sexual excitement or desire;

- The persistent genital arousal may be triggered not only by sexual activity but by nonsexual stimuli as well (e.g., vibrations from a car) or by no apparent stimulus at all; and most importantly,

- The persistent genital arousal is experienced as unbidden, intrusive, and unwanted

- There is at least a moderate or greater feeling of distress associated with the experience 10.

The unremitting nature of the symptoms, predisposes them to become severely depressed and even suicidal 11.

PGAD treatment

Currently there is no generally accepted treatment for PGAD, current interventions focus on symptom management 26. Both biological and psychological modes of treatment have been considered. Electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) if co-morbid with mood symptoms 27 and cognitive behavioral therapy 28. Pharmacologic strategies have included the use of antidepressants 29, olanzapine, risperidone, carbamazepine, valproic acid, opioid agonist tramadol, varenicline 19. Duloxetine and pregabalin were tried in two women with PGAD. One had full remission (duloxetine), and the other had a substantial improvement (pregabalin) 30. Validation, psychoeducation, identification of triggers, distraction techniques, and pelvic massage to decrease the pelvic floor tension have been attempted 26.

- Aswath M, Pandit LV, Kashyap K, Ramnath R. Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38(4):341–343. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.185942 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4980903[↩][↩]

- First Reported Case of Isolated Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder in a Male. Case Reports in UrologyVolume 2015, Article ID 465748, 3 pages http://downloads.hindawi.com/journals/criu/2015/465748.pdf[↩][↩]

- Goldstein I. Persistent Sexual Arousal Syndrome. [Last retrieved on 2007 May 04];Boston University Medical Campus Institute for Sexual Medicine. 2004 Mar 01;[↩]

- Persistent genital arousal disorder in a male: a case report and analysis of the cause. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, March 2013, Volume 6, Number 1 https://www.bjmp.org/files/2013-6-1/bjmp-2013-6-1-a605.pdf[↩]

- M. P. Kafka, “Hypersexual disorder: a proposed diagnosis for DSM-V,” Archives of Sexual Behavior, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 377–400, 2010.[↩]

- Leiblum SR, Nathan SG. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome: A newly discovered pattern of female sexuality. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:365–80.[↩]

- S. R. Leiblum and S. G. Nathan, “Persistent sexual arousal syndrome: a newly discovered pattern of female sexuality,” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 365–380, 2001.[↩]

- Leiblum SR. Persistent genital arousal disorder: An update of theory and practice. The Female Patient. 2009;34:19–20.[↩]

- D. Goldmeier, A. Mears, J. Hiller, and T. Crowley, “Persistent genital arousal disorder: a review of the literature and recommendations formanagement,” International Journal of STD and AIDS, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 373–377, 2009.[↩][↩]

- Leiblum S, Brown C, Wan J, Rawlinson L. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome: A descriptive study. J Sex Med. 2005;2:331–7.[↩][↩]

- Leiblum S, Seehuus M, Goldmeier D, Brown C. Psychological, medical, and pharmacological correlates of persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1358–66.[↩][↩]

- Cohen SD. Diagnosis and Treatment of Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder. Rev Urol. 2017;19(4):265–267. doi:10.3909/riu0784 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5811885[↩]

- Leiblum SR, Nathan SG. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome: a newly discovered pattern of female sexuality. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:365–380.[↩]

- Waldinger MD, Schweitzer DH. Persistent genital arousal disorder in 18 Dutch women: Part II. A syndrome clustered with restless legs and overactive bladder. J Sex Med. 2009;6:482–97.[↩]

- Leiblum SR, Chivers ML. Normal and persistent genital arousal in women: New perspectives. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33:357–73.[↩]

- Carvalho J, Veríssimo A, Nobre PJ. Psychological factors predicting the distress to female persistent genital arousal symptoms. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41:11–24.[↩]

- Waldinger MD, Venema PL, van Gils APG, de Lint GJ, Schweitzer DH. Stronger evidence for small fiber sensory neuropathy in restless genital syndrome: two case reports in males. J Sex Med 2011; 8:325-30[↩]

- Goldmeier D, Mears A, Hiller J, Crowley T. BASHH Special Interest Group for Sexual Dysfunction. Persistent genital arousal disorder: A review of the literature and recommendations for management. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:373–7.[↩]

- Korda JB, Pfaus JG, Goldstein I. Persistent genital arousal disorder: A case report in a woman with lifelong PGAD where serendipitous administration of varenicline tartrate resulted in symptomatic improvement. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1479–86.[↩][↩]

- Goldstein I, De EJ, Johnson J. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome and clitoral priapism. In: Goldstein I, Meston C, Davis S, Traish A, editors. Women’s Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment. London, England: Taylor & Francis; 2006. pp. 674–85.[↩]

- S. R. Leiblum and D. Goldmeier, “Persistent genital arousal disorder in women: case reports of association with antidepressant usage and withdrawal,” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 150–159, 2008.[↩]

- Amsterdam A, Abu-Rustum N, Carter J, Krychman M. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome associated with increased soy intake. J Sex Med. 2005;2:338–40.[↩]

- Mahoney S, Zarate C. Persistent sexual arousal syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33:65–71.[↩]

- Komisaruk BR, Lee HJ. Prevalence of sacral spinal (Tarlov) cysts in persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2047–56.[↩]

- T. M. Facelle, H. Sadeghi-Nejad, and D. Goldmeier, “Persistent genital arousal disorder: characterization, etiology, and management,” J Sex Med. 2013 Feb;10(2):439-50. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02990.x. Epub 2012 Nov 15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02990.x[↩]

- Leiblum S. Persistent Genital Arousal Disorder: What It Is and What It Isn’t. Contemporary Sexuality. 2006 Jul 26;[↩][↩]

- Korda JB, Pfaus JG, Kellner CH, Goldstein I. PGAD: case report of long term symptomatic management with ECT. J Sex Med 2009; 6:2901-9[↩]

- Hiller J, Heskster B. Couple’s therapy with cognitive behavioural techniques for PSAS. Sexual and Relationship Therapy 2007; 22:91-96[↩]

- Leiblum S. Persistent genital arousal disorder. In: Leiblum S, editor. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 54–83.[↩]

- Philippsohn S, Kruger TH. Persistent genital arousal disorder: Successful treatment with duloxetine and pregabalin in two cases. J Sex Med. 2012;9:213–7.[↩]