Panayiotopoulos syndrome

Panayiotopoulos syndrome also known as early onset childhood occipital epilepsy, is a benign childhood epilepsy with predominant autonomic symptoms 1. Panayiotopoulos syndrome starts in early childhood, usually between the ages of 3-6 years, but children from 1-13 years have been described 2. Both boys and girls can develop Panayiotopoulos syndrome. It occurs in approximately 3 out of 50 (6%) children between the ages of 1-15 who have epilepsy, with 13% of the cases occurring between 3 and 6 years 3. Panayiotopoulos syndrome can have varied clinical presentations resulting in diagnostic dilemma.

Seizures in Panayiotopoulos syndrome usually start as focal seizures that evolve to a generalized seizure.

- During a seizure, a child may look pale, complain of feeling sick and may vomit.

- They may faint and pupils may dilate or get large.

- They often can keep interacting with the people around them.

- Eyes may turn to one side and tonic-clonic movements may occur in some children.

- During a seizure, some children may be unable to see (lose vision temporarily), see flashing colorful or bright lights, or have blurry vision.

Seizures happen at any time during the day. Most often they happen during sleep or shortly after falling asleep.

Seizures tend to be prolonged, lasting 1 to 30 minutes. Longer seizures (lasting up to 2 hours) occur in 21-50% of children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome. The longer the seizures last, the more likely they will progress to generalized tonic-clonic movements.

The seizure symptoms of Panayiotopoulos syndrome are frequently mistaken as non-epileptic conditions, such as fainting, migraine, cyclic vomiting syndrome, motion sickness, sleep disorder, or stomach flu.

Children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome mostly have normal physical and cognitive development.

Abnormalities that cause seizures and can be seen on EEG (electrocephalograph) commonly come from the occipital lobes, which is located in the back of the brain.

Education and counseling of the parents/caregivers about its benign nature and excellent prognosis are important aspects of management.

Generally the outlook for children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome is good.

- Many children have few seizures during the course of the disease. Up to half of children have fewer than 4 seizures total.

- Children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome will typically have normal physical and cognitive development despite the prolonged seizures.

- Nearly all children will stop having seizures 2-3 years after the first seizure.

- The risk of epilepsy in adult life is not higher than in the general population.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome genetics

A minority of people (about 17%) have a family history of seizures or epilepsy. However, no specific genes have been definitively associated with Panayiotopoulos syndrome.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome cause

The cause of Panayiotopoulos syndrome involves an epileptogenic activation of the low threshold central autonomic areas. However, the signals are not strong enough to activate the cortical areas that usually bring about motor or sensory manifestations. Hence, most of the seizures have purely autonomic features. However, in some cases, the epileptogenic potential gradually becomes stronger and activates cortical center resulting in secondary generalizations with motor activity 4.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome symptoms

The main seizure type seen in Panayiotopoulos syndrome is autonomic epileptic seizure, with vomiting being the predominant symptom 1. Other autonomic symptoms reported are dilated pupils (mydriasis) or small pupil (miosis), pallor, cyanosis (bluish or greyish color of the skin, nails, lips or around the eyes), flushing, cardiorespiratory (apnea/changes in heart rate) and thermoregulatory alterations, urinary and/fecal incontinence, hypersalivation, and altered intestinal motility 4. Behavioral disturbances, headache, or other non-painful cephalic sensations are commonly observed at onset 3. This is usually followed by more conventional manifestations of seizures with the child becoming confused or unresponsive. Eyes may deviate to one side (60%) or there may be staring look. Half of the seizures last for more than 30 min and can end with hemi or generalized convulsions. Other, less frequent ictal features described include aphasia, hemifacial spasms, visual hallucinations, and oropharyngeal movements 5. Cardiorespiratory arrest has also been described in a few cases 5. Fever is a common trigger for focal autonomic seizures in Panayiotopoulos syndrome as seen in our case 6.

Two-thirds of the seizures occur during sleep or brief daytime naps 7. Panayiotopoulos syndrome is often misdiagnosed if the autonomic symptoms are not recognized as seizure events. Diagnosis can be confused with other nonepileptic conditions such as atypical migraine, motion sickness, gastroenteritis, encephalitis, or syncope 4. The list below shows the various atypical presentations of Panayiotopoulos syndrome reported in the literature.

Atypical presentations of panayiotopoulos syndrome reported in literature

- Respiratory arrest 5

- Priapism 8

- Encephalopathy 9

- Syncopal attacks 10

- Cardiorespiratory arrest 4

- Intractable vomiting 11

Panayiotopoulos syndrome diagnosis

Panayiotopoulos syndrome is diagnosed based on description of the seizures.

Before you can track seizures, you need to know what to look for. Seizures can be broken down into 4 phases:

- Prodrome: behaviors or feelings that occur hours to days before a seizure

- Aura: the actual start of a seizure and may be thought of as a ‘warning’

- Ictus: the seizure event

- Postictal: the recovery period after the seizure

When watching a seizure, try to note what happens in each phase of the seizure – before, during and after the event. Write down what happens as soon as you can – it’s easy to forget details when you don’t write them down. Here’s a list of things that may happen during a seizure. Remember that what you see will depend on the type of seizure that occurs.

Behavior before the seizure:

- What was the person doing at the time of the event?

- Was there a change in mood or behavior hours or days before?

- Was there a warning or aura right before the seizure?

When the event occurs: Note date and time.

Possible triggers: Note patterns or any factors that may make event more likely to occur.

- Time of day or month

- For females, note the day of your menstrual cycle, if pregnant, on any birth control or other hormonal treatment,

- Missed or late medicines, changes in medicine doses

- Not sleeping regularly, not enough sleep, other sleep problems

- Not eating regularly, bothered by specific foods

- During or after exercise, note the kind of exercise such as jogging

- During or after fast breathing

- Alcohol or other drug use

- Emotional stress, worry, excitement

- Sounds, flashing lights or patterns, bright sunlight

- Other illnesses or infections

- When taking other medicines, over-the-counter products, or supplements

What happens during the event: Note changes in the following…

- Awareness, alertness, confusion

- Ability to talk and understand – clear speech, responds with only a few words or noises, speech doesn’t make sense, unable to talk

- Thinking, remembering, emotions, perceptions

- Seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling, feeling – May have different or unusual sensations, or may sense something that is not really there

- Facial expression – staring, twitching, eye blinking or rolling, drooling

- Muscle tone – body becomes stiff or limp

- Movements – jerking or twitching movements, unable to move, body or head turning to one side, falls

- Automatic or repeated movements – lipsmacking, chewing, swallowing, picking at clothes, rubbing hands, tapping feet, dressing or undressing

- Walking, wandering, running

- Color of skin, sweating, breathing

- Loss of bladder or bowel control

Part of body involved: Note where the symptoms started, whether it stayed in that area or spread to other parts of the body, and which side of the body was involved (right, left, or both).

What happens after the event (postictal or recovery period): Is the person:

- Able to respond to voice or touch

- Aware of their own name, observer’s name, place, time

- Able to remember what happened

- Able to talk or communicate

- Weak or numb in any part of the body

- Having a change in mood or behavior

- Tired or need to sleep

- Other symptoms – for example headache, upset stomach, pain

How long it lasted:

- Length of aura or warning

- Length of seizure – from beginning to end, but not counting the recovery period

- Length of recovery or postictal period – how long before the person returns to normal activity

Tests that may be done include the following

EEG (electroencephalogram)

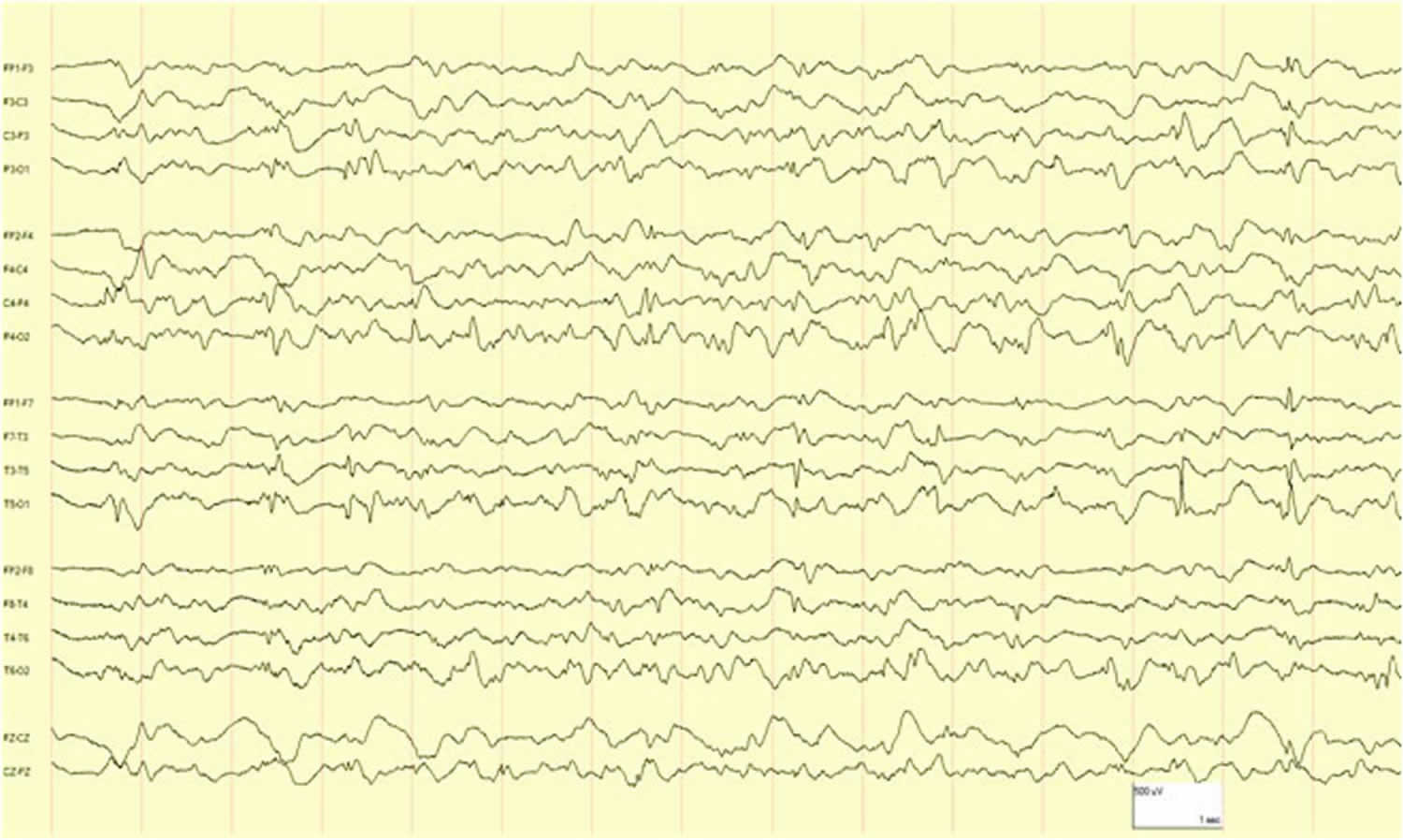

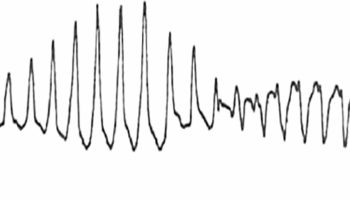

The majority of children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome have spike discharges on their electroencephalogram (EEG) in many areas. These abnormalities seem on the EEG are mostly found in the occipital area of the brain.

- These spike discharges can shift slightly from one EEG to another and/or multiple foci often with occipital predominance, suggesting the possibility that the site of seizure onset is usually occipital 4. Spikes will often be more frequent when children close their eyes or are not fixating on an object, a phenomenon known as “fixation-off sensitivity.”

- Background activity is normal.

- An EEG with some sleep is important to obtain if possible.

However, normal EEG recordings may occur in 25% of children 7. At least five of the following criteria need to be present to make a diagnosis of Panayiotopoulos syndrome 3:

- Infrequent seizures,

- Prolonged seizures 5 minutes,

- Ictal vomiting, eye deviation,

- Autonomic manifestations (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, and hypotension),

- behavioral and altered consciousness.

Figure 1. Panayiotopoulos syndrome EEG

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

The MRI, if done, is typically normal in children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome treatment

Seizures in children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome are often infrequent and antiseizure medication may not be needed.

When seizures are more frequent, the seizures can be controlled with antiseizure medications like oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), carbamazepine (Tegretol or Carbatrol), levetiracetam (Keppra), gabapentin (Neurontin), zonisamide (Zonegran), lacosamide (Vimpat), and others.

Because children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome often have long seizures, they may need emergency medical treatment. A rescue therapy may be helpful, such as diazepam rectal gel or another form of benzodiazepine given in the nose, under the tongue, or between the cheek and gum.

Parents of children with Panayiotopoulos syndrome should talk to the treating neurologist or health care provider to learn about seizure emergencies. Talk to the health care team about what kind of rescue therapy could be used and when to use it.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome prognosis

Panayiotopoulos syndrome prognosis is usually good with remission usually occurring 1–2 years after onset. Around 25% have frequent seizures, but the outcome is still favorable 4. Prolonged seizures do not appear to result in residual deficits or have adverse prognostic significance. Around 20% of cases may progress to rolandic epilepsy which usually remits. The risk of epilepsy in adult life appears to be no higher than in the general population 4.

In case of frequent seizures, rescue therapy with benzodiazepines can be advocated at home/school. Prophylactic therapy with antiepileptic drugs is indicated when seizures are unusually frequent, distressing, or otherwise significantly affecting the child’s quality of life. Carbamazepine, sodium valproate, and levetiracetam have been used in various studies with good results 4.

- Zaki SA, Verma DK, Tayde P. Panayiotopoulos syndrome in a child masquerading as septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20(6):361–363. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.183912 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4922291[↩][↩]

- Panayiotopoulos Syndrome. https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/types-epilepsy-syndromes/panayiotopoulos-syndrome[↩]

- Girish M, Mujawar N, Dandge V. Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:420–1.[↩][↩][↩]

- Mujawar QM, Sen S, Ali MD, Balakrishnan P, Patil S. Panayiotopoulos syndrome presenting with status epilepticus and cardiorespiratory arrest: A case report. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:754–7.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Dirani M, Yamak W, Beydoun A. Panayiotopoulos syndrome presenting with respiratory arrest: A case report and literature review. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2015;3:12–4.[↩][↩][↩]

- Cordelli DM, Aldrovandi A, Gentile V, Garone C, Conti S, Aceti A, et al. Fever as a seizure precipitant factor in Panayiotopoulos syndrome: A clinical and genetic study. Seizure. 2012;21:141–3.[↩]

- Koutroumanidis M. Panayiotopoulos syndrome. BMJ. 2002;324:1228–9.[↩][↩]

- Brabec J, Chaudhary S, Ng YT. Ictal priapism as an autonomic manifestation of Panayiotopoulos syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:1686–8.[↩]

- Nishikura N, Yoshioka S, Takano T. A girl case of panayiotopoulos syndrome with encephalopathy-like manifestation. No To Hattatsu. 2012;44:333–5.[↩]

- Koutroumanidis M, Ferrie CD, Valeta T, Sanders S, Michael M, Panayiotopoulos CP. Syncope-like epileptic seizures in Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Neurology. 2012;79:463–7.[↩]

- Ozkara C, Benbir G, Celik AF. Misdiagnosis due to gastrointestinal symptoms in an adolescent with probable autonomic status epilepticus and Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:703–4.[↩]