Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome also called Vogt Koyanagi Harada disease or VKH disease, is a multisystem autoimmune inflammatory disease that affects several parts of your body, including your eyes, ears, nervous system, and skin 1. The signs and symptoms of Vogt Koyanagi Harada disease are caused by chronic inflammation of melanocytes. Melanocytes are specialized cells that produce a pigment called melanin. Melanin is the substance that gives skin, hair, and eyes their color. Melanin is also found in other parts of the body, such as the retina of the eyes, where it plays a role in normal vision, and in the inner ear, where it is thought to be involved in hearing 2. People with VKH disease usually develop vision and hearing problems first, followed by signs of skin problems 3. The most common symptoms include headaches, inflammation of all layers of the colored part of the eye (panuveitis), white patches of skin (vitiligo), hair loss (alopecia), dizziness and nausea (inner ear related problems), and vision and hearing loss. Neurological symptoms may also occur 4. The exact cause of Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome is not well understood, but research suggests it is an autoimmune disease. It is more common in people with darker skin color including Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, and Native American populations 1. Vogt Koyanagi Harada disease is treated with corticosteroids and other medications 1.

VKH disease is uncommon, but it may be seen in Asian (primarily from eastern and southeastern Asia), Middle Eastern, Hispanic, and Native American populations. The disorder is less common in whites and blacks from sub-Saharan Africa 5.

In Japan, VKH disease represents 7-8% of all patients with uveitis 6. Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome rarely is seen in Northern European individuals. The manifestations of VKH disease in whites resemble those in the Japanese population, but cutaneous signs are much rarer 1.

In a report from the National Eye Institute, Nussenblatt et al noted that among patients with VKH disease in the study, 50% were white, 35% were African American, and 13% were Hispanic; however, most patients had remote Native American ancestry 7.

VKH disease is one of the most common forms of uveitis among darkly pigmented races. Individuals with VKH disease most likely have an immunogenetic predisposition that is probably more common in certain ethnic groups with increased skin pigmentation, such as Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, and Native American populations. Moreover, VKH disease is distinctly uncommon in Africans, reaffirming that skin pigmentation alone is not a predisposing factor in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Females are more commonly affected than males; the female-to-male ratio in most large series is 2:1.

Onset typically occurs at around 30 or 40 years of age, but cases have been reported among children as young as four years old. The age of onset of VKH disease has been reported to range from 3-89 years, with the maximum frequency in persons in their fourth decade of life. While VKH disease is seen more frequently in the adult population, it has been reported in children as young as age 3 years 8.

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome cause

The exact cause of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease is not well understood, but research suggests it is an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks its own pigment cells (melanocytes), possibly in response to an infection (such as a virus) 3. The strong association between VKH disease and certain ethnic groups suggests that genetic factors may be involved. VKH disease occurs more commonly in patients with a genetic predisposition to the disease, including those from Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, and Native American populations. Several human leukocyte antigen (HLA) associations have been found in patients with VKH disease, including HLA-DR4, HLA-DR53, and HLA-DQ4 1.

VKH disease is currently considered to be a T-cell–mediated autoimmune response directed against melanocytes, although the exact antigens involved are incompletely understood 1. However, the pathogenesis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease is uncertain, although the wide spectrum of findings in this disorder suggests a central mechanism to account for the multisystemic manifestations. Inflammation and loss of melanocytes have been described in a number of tissues, including the skin, inner ear, meninges, and uvea. These histopathologic changes suggest an infectious or autoimmune basis for the disease.

The possibility that Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease has an autoimmune pathogenesis is supported by the statistically significant frequency of HLA-DR4, an antigen commonly associated with other autoimmune diseases.

An autoimmune reaction seems to be directed against an antigenic component shared by uveal, dermal, and meningeal melanocytes. The exact target antigen has not been identified, but possible candidates include tyrosinase- or tyrosinase-related proteins 9, an unidentified 75-kd protein obtained from cultured human melanoma cells (G-361) 10, and S-100 protein 11. Evidence suggests that Th1 and Th17 subsets of T cells together with the cytokines interleukin (IL)-7, IL-17 and IL-23 are likely involved in the initiation and maintenance of the inflammatory process 12.

VKH disease can be associated with other autoimmune disorders, such as autoimmune polyglandular syndrome 13, hypothyroidism, Hashimoto thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus 14, Guillain-Barré syndrome 15 and immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy 16. Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome has also been reported to be linked to malignant lymphoma 17.

Immunologic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) lymphocytes in VKH disease and studies of human uveal melanocytes show that uveal pigment can stimulate lymphocyte cultures from patients with VKH syndrome. Lymphocytes of peripheral blood and CSF from these patients may reveal in vitro cytotoxicity against allogenic melanoma cells.

Circulating antibodies against a retinal photoreceptor region have been detected in patients with Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome.

The clinical course of VKH disease with an influenzalike illness suggests a viral or postinfectious origin. Some studies invoke a possible role of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation 18 or cytomegalovirus infection in this disease 19. Although a viral cause has been proposed, however, no virus has been isolated or cultured from patients with VKH disease. Nonetheless, Schlaegel and Morris found viruslike inclusion bodies in the subretinal fluid of a patient with VKH syndrome 20.

Single reports of patients developing VKH disease after cutaneous injury have been noted 21, as well as 2 cases of this condition occurring after bacillus Calmette Guérin (BCG) therapy for melanoma 22 and 1 case following surgery for metastatic malignant melanoma 23. Case reports indicate that even an indirect trauma in melanocyte-containing tissue may induce an inflammatory response in the eye, with VKH disease following a closed head trauma 24.

A study revealed that a decreased vitamin D-3 level has been associated with active intraocular inflammation in patients with VKH disease 25.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease genetics

Although almost all instances of VKH syndrome are sporadic, and familial cases are rare, some authors suggest that the condition may be inherited, probably as an autosomal recessive trait.

The strong association between VKH disease and certain racial and ethnic groups suggests that the disorder may have an immunogenetic predisposition 26. HLA typing can be useful to identify these common genetic factors, with several HLA haplotypes apparently being more common in certain populations with VKH disease.

Among Japanese patients, HLA-DR4, HLA-DR53, and HLA-DQ4 are associated strongly with the disease 27. In Chinese patients, HLA associations are seen with HLA-DR4, HLA-DR53, and HLA-DQ7 28. In a mixed group of American patients, Davis and colleagues found an association with HLA-DR4 and HLA-DR53, while HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR4 were reported in Hispanic patients living in southern California 29.

An association with HLA-DR4, HLA-DRw53, and HLA-DQw3 has been found in subjects of Native American ancestry, and HLA-DR4 also was found to be significantly related to VKH syndrome in white Europeans, specifically in Italian patients 30.

Data indicate that patients with VKH disease are sensitized to melanocyte epitopes and display a peptide-specific Th1 cytokine response. Patients bearing HLA-DRB1*0405 recognize a broader melanocyte-derived peptide repertoire, so the presence of this allele increases susceptibility to the development of VKH disease 31. In a group of French VKH disease DRB1*04-positive patients, the HLA-DRB1*0405 subtype was found in 71% of them 32.

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome symptoms

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease is initially characterized by headaches, very deep pain in the eyes, dizziness (vertigo), and nausea. These symptoms are usually followed in a few weeks by eye inflammation (uveitis) with sudden loss of vision, blurring of vision, eye pain and sensitivity to light. This may occur in both eyes at the same time or in one eye first and, a few days later, in the other. The retina may detach and hearing loss may become apparent. Sometimes there are also other symptoms as well, including dizziness. After weeks or months, most people also have skin problems. According to the progression of the symptoms there are 4 stages of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: early phase or prodromal, acute uveitic stage, chronic convalescent stage, and chronic recurrent stage 33.

Prodromal stage

Early phase or prodrome typically lasts for 7-10 days and is characterized by flu-like symptoms, such as the following 33:

- Low-grade fever

- Headache

- Neck stiffness and pain on the back of the head (meningismus)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Vertigo or dizziness

- Orbital pain

- Hearing loss and inner ear related disorders, including distorted hearing (dysacusis), ringing in the ears (tinnitus), and a kind of dizzy, spinning sensation (vertigo)

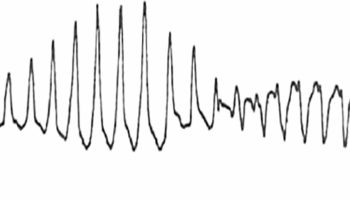

CSF pleocytosis occurs in more than 80% of patients during this stage. Photophobia and tearing may develop, and patients also may note that their skin and hair is sensitive to touch during this stage.

Uncommon manifestations during the prodrome include cranial nerve palsies and optic neuritis. Some patients may not develop or report the symptoms characteristic of the prodrome.

There may be other less common symptoms such as double vision and drooping of the eyelids due to cranial nerve palsies 1.

These symptoms are usually followed in a few weeks by eye inflammation (panuveitis) that may occur in both eyes at the same time or in one eye first and, a few days later, in the other. The symptoms may include:

- Sudden vision loss in one or both eyes

- Eye pain

- Eye swelling and irritation

- Dark, floating spots in the vision (floaters) indicating retinal detachment

The convalescent stage follows in a few weeks. This stage is characterized by changes in the eyes and skin. The changes in the eyes may include loss of color in the layer of the eye filled with blood vessels that nourish the retina (choroid) resulting in an orange-red discoloration or “sunset glow fundus” (due to the resolution of the retinal detachments), as well as the development of small yellow nodules in parts of the retina. Changes in the coloring of the skin and hair are usually seen three months after symptoms first appear, and they are often permanent 1. The chronic stage can last for several months to several years 1.

During the recurrent stage, people with VKH disease may develop recurrent or chronic eye problems. Common eye complications may include cataracts, glaucoma, and new, abnormal blood vessels growing under the retina (choroidal neovascularization), which can lead to scarring (subretinal fibrosis) 1.

Uveitic or acute stage

The acute uveitic stage follows the prodromal stage by several days in most patients and typically lasts for several weeks 34. During this stage, the most common symptom is acute bilateral blurring of vision. As many as 70% of patients present with bilateral blurring of vision; in most of the remaining patients, the fellow eye is involved within several days.

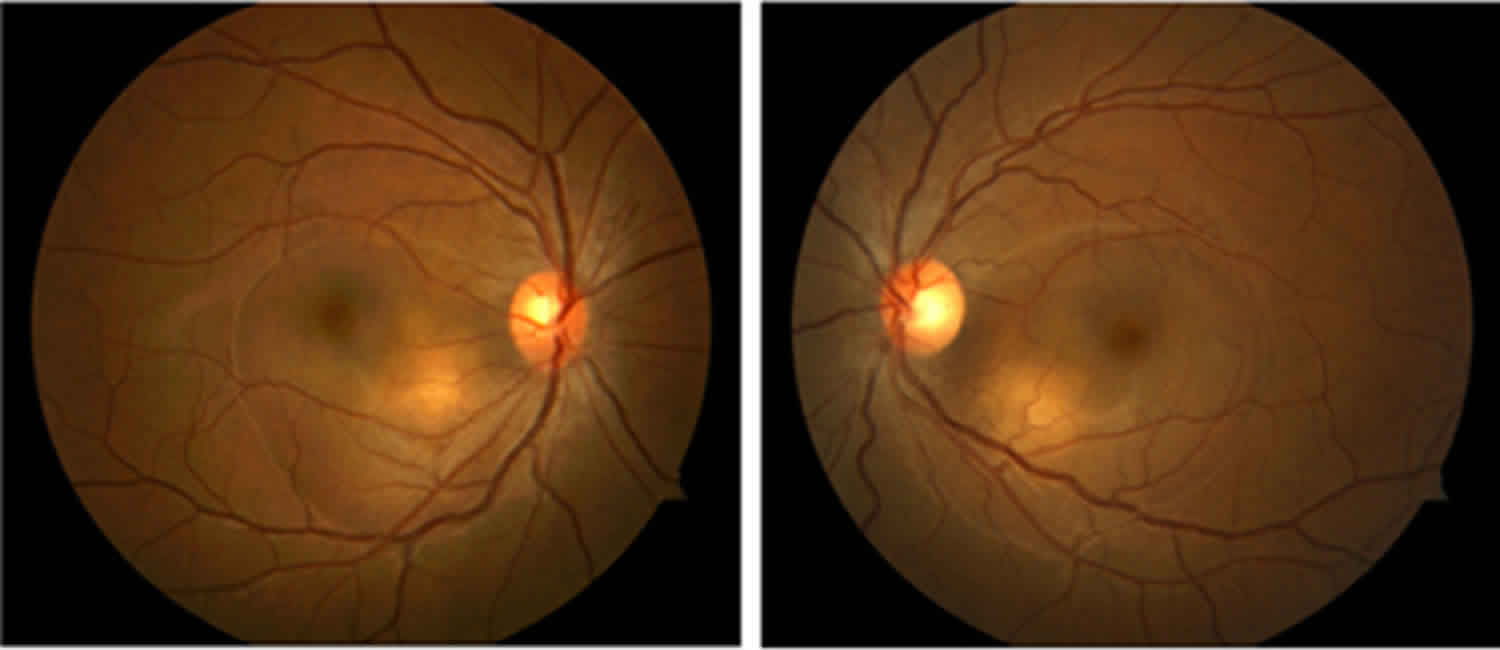

Clinically, this stage manifests as bilateral posterior uveitis with retinal edema, exudative retinal detachments, optic disc hyperemia or edema, posterior choroid thickening, and, eventually, serous retinal detachments. Often, an accompanying anterior uveitis characterized by mutton-fat keratic precipitates and iris nodules are present. At this stage, an accompanying anterior uveitis can occur. The intraocular pressure may be elevated because of forward rotation of the lens-iris diaphragm.

Chronic convalescent stage

Many patients with acute VKH disease go on to the chronic convalescent stage of VKH, about 3–4 months after the onset of VKH disease 35. This usually lasts for some months or years 34. The chronic convalescent stage is characterized by changes in the eyes and skin. The changes in the eyes may include loss of color in the layer of the eye filled with blood vessels that nourish the retina (choroid), as well as the development of small yellow nodules in parts of the retina. Depigmentation of the choroid begins within the first 3 months after the onset of the disease, resulting in the sunset glow fundus. Areas of hyperpigmentation also may develop in the fundus. Dalen-Fuchs nodules may be seen in the peripheral and midperipheral retina. These nodules are small, yellow lesions that typically are located in the midperiphery of the retina. Eventually, the lesions fade and become atrophic.

Skin changes may include the development of smooth, white patches in the skin caused by the loss of pigment-producing cells (vitiligo). These white patches are usually distributed over the head, eyelids and torso. Other signs of depigmentation include the Sugiura sign (perilimbal depigmentation), more common in patients of Japanese descent. [52] The vitiligo tends to be distributed symmetrically over the head, eyelids, and trunk.

The chronic convalescent stage can last for several months to several years.

Chronic recurrent stage

25% of patients with acute VKH develop the chronic recurrent phase of the disease 6–9 months after initial presentation 36. During the chronic recurrent stage, patients may develop recurrent or chronic anterior uveitis. In some patients, low-grade choroidal inflammation may accompany the anterior uveitis, which may require indocyanine green angiography for visualization 37. Recurrent posterior uveitis with serous retinal detachment is rare. Patients treated inadequately with corticosteroids and/or immunomodulator therapy for 6 months or less may be at higher risk for recurrent serous retinal detachment 38. At this stage, the anterior uveitis is typically of granulomatous nature, with the presence of mutton fat keratic precipitates and Koeppe/Busacca nodules 39.

Ocular complications are relatively common during this stage and include cataracts, glaucoma, choroidal neovascularization, and subretinal fibrosis.

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome complications

Complications of Vogt Koyanagi Harada disease include the following:

- Cataract

- Closed-angle glaucoma – Pupillary block, forward rotation of the ciliary body

- Open-angle glaucoma

- Subretinal fibrosis

- Choroidal neovascularization

- Neovascularization of the optic disc

- Pigmentary changes of the fundus

- Optic atrophy

- Neurologic manifestations – Many of the neurologic manifestations may persist for weeks; most signs and symptoms resolve with corticosteroid therapy, although severe meningoencephalitic impairment has been reported

- Cutaneous manifestations – Most of the integumentary changes, including alopecia, poliosis, and vitiligo, persist despite therapy; cutaneous changes may be permanent

- Auditory manifestations – Inner ear manifestations typically respond to corticosteroid therapy within weeks to months; hearing is restored completely in most patients with VKH disease

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for VKH disease includes inflammation of both eyes, no evidence of another ocular disease causing the inflammation, and no history of trauma or ocular surgery. An international group of experts has established three categories of disease 40:

- Complete VKH disease: diffuse choroiditis involving both eyes that may include serous retinal detachments. Inflammation of the iris and ciliary body may develop in some patients. The complete form of the disease includes neurologic signs such as ringing in the ears (tinnitus), neck stiffness, and/or cells in the cerebrospinal fluid (pleocytosis) as well as dermatological signs such as white patches on the arms or torso, sudden loss of hair (alopecia), or loss of color of the hair, eyelashes or eyelids (poliosis)

- Incomplete VKH disease: similar eye disease as patients with complete VKH disease but do not have both neurologic and dermatological signs. Patients must have either the neurologic manifestations or dermatological signs.

- Probable VKH disease: similar eye disease as patients with complete VKH disease but without neurologic and dermatological signs.

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome treatment

Management of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease may involve various specialists including dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and neurologists 4. Experts agree that successful therapy for VKH disease involves early and aggressive treatment with systemic corticosteroids (steroids) 33. Even when the symptoms of VKH disease get better with steroid therapy, many people need to slowly decrease the dose of steroid over a period of 3-6 months so that their symptoms do not return 1.

For people who don’t respond to steroids or who cannot tolerate the side effects, a type of therapy that changes the response of the body’s immune system called immunomodulatory therapy may be tried 1. While there is increasing evidence supporting the use of immunomodulatory therapy in almost all people with VKH disease, there is ongoing research to determine exactly when this treatment should be started and who should receive it 41. Surgery for glaucoma is necessary in some people 1. Other treatments for VKH disease are symptomatic and supportive 33.

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome prognosis

Treatment of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VHK) disease usually improves both the vision and hearing loss caused by the disease. People who are treated early in the course of the disease tend to recover more fully than those who are treated later. Other factors that may affect recovery include response to treatment and severity of symptoms. Full recovery of vision is also dependent on the ability to treat secondary visual complications including cataracts, glaucoma, and/or the growth of new blood vessels in the choroid layer of the eye (choroidal neovascularization). Complications are typically more severe in children than in adults, which can lead to greater risk of permanent vision loss for children 1.

Even with treatment early in the course of VKH disease, it can take a few weeks or months for neurological symptoms (ringing in the ears and stiff neck) and inner ear symptoms (dizziness and nausea) to get better completely. Some people do not fully recover all of their sight or hearing. Hair loss (alopecia), hair color changes, and/or the white patches of skin (vitiligo) may be permanent as well 1.

Long-term complications of VKH disease include reversible and irreversible vision loss. In patients with Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome, vision loss is often is due to cataracts, glaucoma, and choroidal neovascularization (with this last being a major cause of late vision loss). Patients with optic disc swelling may develop visual field defects that persist following resolution of the inflammation 42. Final visual outcome depends on the rapidity and appropriateness of treatment 43.

The prognosis may be improved by the use of early, high-dose corticosteroids during the acute phase of the disease and afterward a slow tapering reduction in dosage until therapy is discontinued. In most cases, therapy should not be discontinued during the 3 months after onset of the disease, because of the high rate of recurrence during this period. Many patients require a tapering period of at least 3-6 months before the corticosteroids can be discontinued.

Ocular complications of VKH disease are more severe in children than in adults, leading to rapid deterioration in vision.

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) Disease. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1229432-overview[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Bismuth K & Arnheiter H. Neural Crest Cell Diversification and Specification: Melanocytes. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. 2009; 143-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008045046-9.01038-X[↩]

- Fang W & Yang P. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada. Current Eye Research. Jul 2008; 33(7):517-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18600484[↩][↩]

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=en&Expert=3437[↩][↩]

- Chee SP, Jap A, Bacsal K. Prognostic factors of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Singapore. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Jan. 147(1):154-161.e1.[↩]

- Ohguro N, Sonoda KH, Takeuchi M, Matsumura M, Mochizuki M. The 2009 prospective multi-center epidemiologic survey of uveitis in Japan. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012 Sep. 56(5):432-5.[↩]

- Nussenblatt RB. Clinical studies of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada’s disease at the National Eye Institute, NIH, USA. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1988. 32(3):330-3.[↩]

- Martin TD, Rathinam SR, Cunningham ET Jr. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and causes of vision loss in children with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in South India. Retina. 2010 Jul-Aug. 30 (7):1113-21.[↩]

- Hashimoto T, Takizawa H, Yukimura K, Ohta K. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease associated with brainstem encephalitis. J Clin Neurosci. 2009 Apr. 16(4):593-5.[↩]

- Kondo I, Yamagata K, Yamaki K, Sakuragi S. [Analysis of the candidate antigen for Harada’s disease]. Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1994 Jun. 98(6):596-603.[↩]

- Gloddek B, Lassmann S, Gloddek J, Arnold W. Role of S-100beta as potential autoantigen in an autoimmune disease of the inner ear. J Neuroimmunol. 1999 Nov 1. 101(1):39-46.[↩]

- Yang Y, Xiao X, Li F, Du L, Kijlstra A, Yang P. Increased IL-7 expression in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012 Feb. 53(2):1012-7.[↩]

- Kluger N, Mura F, Guillot B, Bessis D. Vogt-koyanagi-harada syndrome associated with psoriasis and autoimmune thyroid disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008. 88(4):397-8.[↩]

- Suzuki H, Isaka M, Suzuki S. Type 1 diabetes mellitus associated with Graves’ disease and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Intern Med. 2008. 47(13):1241-4.[↩]

- Najman-Vainer J, Levinson RD, Graves MC, Nguyen BT, Engstrom RE Jr, Holland GN. An association between Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001 May. 131(5):615-9.[↩]

- Matsuo T, Masuda I, Ota K, Yamadori I, Sunami R, Nose S. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome in two patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Acta Med Okayama. 2007 Oct. 61(5):305-9.[↩]

- Hashida N, Kanayama S, Kawasaki A, Ogawa K. A case of vogt-koyanagi-harada disease associated with malignant lymphoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005 May-Jun. 49(3):253-6.[↩]

- Sunakawa M, Okinami S. Epstein-Barr virus-related antibody pattern in uveitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1985. 29(4):423-8.[↩]

- Sugita S, Takase H, Kawaguchi T, Taguchi C, Mochizuki M. Cross-reaction between tyrosinase peptides and cytomegalovirus antigen by T cells from patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2007 Apr-Jun. 27 (2-3):87-95.[↩]

- SCHLAEGEL TF Jr, MORRIS WR. VIRUSLIKE INCLUSION BODIES IN SUBRETINAL FLUID IN UVEO-ENCEPHALITIS. Am J Ophthalmol. 1964 Dec. 58:940-5.[↩]

- Tabbara KF. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome after cutaneous injury. Ophthalmology. 1999 Oct. 106(10):1854-5.[↩]

- Donaldson RC, Canaan SA Jr, McLean RB, Ackerman LV. Uveitis and vitiligo associated with BCG treatment for malignant melanoma. Surgery. 1974 Nov. 76(5):771-8.[↩]

- Sober AJ, Haynes HA. Uveitis, poliosis, hypomelanosis, and alopecia in a patient with malignant melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978 Mar. 114(3):439-41.[↩]

- Accorinti M, Pirraglia MP, Corsi C, Caggiano C. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease after head trauma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007 Sep-Oct. 17(5):847-52.[↩]

- Yi X, Yang P, Sun M, Yang Y, Li F. Decreased 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 level is involved in the pathogenesis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease. Mol Vis. 2011 Mar 9. 17:673-9.[↩]

- Levinson RD, Du Z, Luo L, Holland GN, Rao NA, Reed EF, et al. KIR and HLA gene combinations in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Hum Immunol. 2008 Jun. 69(6):349-53.[↩]

- Horie Y, Takemoto Y, Miyazaki A, Namba K, Kase S, Yoshida K, et al. Tyrosinase gene family and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Japanese patients. Mol Vis. 2006 Dec 20. 12:1601-5.[↩]

- Hou S, Yang P, Du L, Zhou H, Lin X, Liu X, et al. Small ubiquitin-like modifier 4 (SUMO4) polymorphisms and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome in the Chinese Han population. Mol Vis. 2008. 14:2597-603.[↩]

- Davis JL, Mittal KK, Freidlin V, Mellow SR, Optican DC, Palestine AG, et al. HLA associations and ancestry in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia. Ophthalmology. 1990 Sep. 97(9):1137-42.[↩]

- Pivetti-Pezzi P, Accorinti M, Colabelli-Gisoldi RA, Pirraglia MP. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and HLA type in Italian patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 Dec. 122(6):889-91.[↩]

- Goldberg AC, Yamamoto JH, Chiarella JM, Marin ML, Sibinelli M, Neufeld R, et al. HLA-DRB1*0405 is the predominant allele in Brazilian patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Hum Immunol. 1998 Mar. 59(3):183-8.[↩]

- Abad S, Monnet D, Caillat-Zucman S, Mrejen S, Blanche P, Chalumeau M, et al. Characteristics of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in a French cohort: ethnicity, systemic manifestations, and HLA genotype data. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2008 Jan-Feb. 16(1):3-8.[↩]

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/vogt-koyanagi-harada-disease[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Baltmr A, Lightman S, Tomkins-Netzer O. Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome — current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol 2016; 10: 2345–61.[↩][↩]

- Chee S, Jap A, Bacsal K. Spectrum of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Singapore. Int Ophthalmol 2006: 27: 137–42.[↩]

- O’Keefe G, Rao N. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Surv Ophthalmology 2017; 62: 1–25. DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.05.002[↩]

- Bacsal K, Wen DS, Chee SP. Concomitant choroidal inflammation during anterior segment recurrence in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar. 145(3):480-486.[↩]

- Errera MH, Fardeau C, Cohen D, Navarro A, Gaudric A, Bodaghi B, et al. Effect of the duration of immunomodulatory therapy on the clinical features of recurrent episodes in Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011 Jun. 89(4):e357-66.[↩]

- Rao NA, Gupta A, Dustin L, Chee SP, Okada AA, Khairallah M, et al. Frequency of distinguishing clinical features in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Ophthalmology. 2010 Mar. 117 (3):591-9, 599.e1.[↩]

- Read R, Holland G, Rao N, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol 2001: 131: 647–52. DOI:).1016/S0002-9394(01)00925–4.[↩]

- Urzua CA, Velasquez V, Sabat P, Berger O, Ramirez S, Goecke A, Vásquez DH, Gatica H, Guerrero J.. Earlier immunomodulatory treatment is associated with better visual outcomes in a subset of patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Acta Ophthalmol. Sept 2015; 93(6):e475-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25565265[↩]

- Nakao K, Abematsu N, Mizushima Y, Sakamoto T. Optic disc swelling in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012 Apr. 53(4):1917-22.[↩]

- Read RW, Yu F, Accorinti M, Bodaghi B, Chee SP, Fardeau C, et al. Evaluation of the effect on outcomes of the route of administration of corticosteroids in acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Jul. 142(1):119-24.[↩]