Sulcus vocalis

Sulcus vocalis is used specifically to describe a groove or depression of mucosa along the medial surface of the true vocal fold that is typically found on the leading edge of the vibratory surface 1. Sulcus vocalis is a structural deformity of the vocal ligament 2. It is the focal invagination of the epithelium deeply attaching to the vocal ligament. In the area of the sulcus, the mucosa is scarred down to the underlying vocal ligament and therefore is tethered, giving it a retracted appearance. This inhomogeneous cover of the mucosa of the vocal ligament can lead to voice changes (dysphonia). Most clinicians agree that presentation of sulcus vocalis is hoarseness, vocal fatigue, voice weakness, and increased effort. However, clinicians may disagree on terminology, diagnosis, and treatment of sulcus vocalis 1.

Sulcus vocalis appears to be common with most sulcus vocalis remained undiagnosed because of subclinical symptoms, lack of clinician awareness, and difficulty in identification due to limited availability of laryngeal videostroboscopy. In a study of autopsy specimens by Nakayama et al 3, sulcus vocalis were identified in 20% of specimens. These authors observed 58 cancer patients and reported 28 (48.3%) had sulcus deformities. Bilateral sulcus was found in 7 of 28 (25%) cancer patients and unilateral sulcus was found in 21 of 28 (75%) cancer patients. The authors even compared the presence of sulcus in non-diseased control patients with cancer patients and concluded that sulci were common in cancer group 3. Sunter et al 4 recently found the incidence to be 39% with pathologic sulcus incidence of 23% (a rate that seems very high). This group examined sulcus vocalis types microscopically; they found increased inflammation, fibrosis and degeneration with type 3 sulcus vocalis.

A mucosal bridge is a variation on the simple sulcus and is formed when 2 parallel sulci simultaneously appear on the medial and superior surface of the true vocal fold. This creates an area of normal-appearing mucosa between 2 mucosal defects. These lesions are more difficult to treat than single sulci but fortunately are very rare.

Essentially, no differences exist between vocal fold scarring where an identifiable sulcus is present and scarring where an identifiable sulcus is not present. In either case, an alteration in the normal physiology of vocal fold vibration exists, which affects voice production.

The clinical features of sulcus vocalis include reduced phonation time (aerodynamic), altered fundamental frequency (acoustical), dysphonia, breathiness, harshness, hoarseness of voice (perceptual), vocal fatigue, incomplete glottal closure, interrupted mucosal wave transmission and ‘spindle-shaped’ glottis (physiology) 5.

Currently, examinations such as videolaryngoscopy, videolaryngostroboscopy or suspension microlaryngoscopy has allowed more clinicians to recognize sulcus vocalis, although it is important to consider the data related to the clinical history of vocal alterations 6. While videostroboscopy can help define dysphonia, sulcus vocali diagnosis is usually made with operative direct laryngoscopy.

There are two lines of management: medical (surgical) and non-medical (behavioural modification, counselling and voice therapy) management. Surgical management includes vocal fold medialisation which includes intrafold injection and medialisation surgery. Intrafold injection includes transoral injection with indirect laryngeal mirror, transoral injection with direct laryngoscopy and transcutaneous injection. The medialisation surgery includes surgical augmentation, medial shift of thyroid cartilage and rotation of arytenoid cartilage 7. However, studies report that the impacts of surgeries in sulcus are unpredictable and the goal is usually to reduce the glottic leakage. It may also be possible that the post-operative voice would be even worse than the preoperative voice 8.

Voice therapy includes implementing hygienic, symptomatic, psychogenic, physiologic and eclectic approaches. Voice therapy has limited success in clients with sulcus vocalis 9. In general, voice therapy in sulcus vocalis focuses on reducing strain on vocal folds, reducing compensatory voice changes and optimising the voice production subsystems, thereby increasing the vocal efficiency. However, there is a need to systematically document the voice profile of clients with sulcus vocalis in order to understand their voice characteristics and determine the efficacy of voice therapy for such individuals.

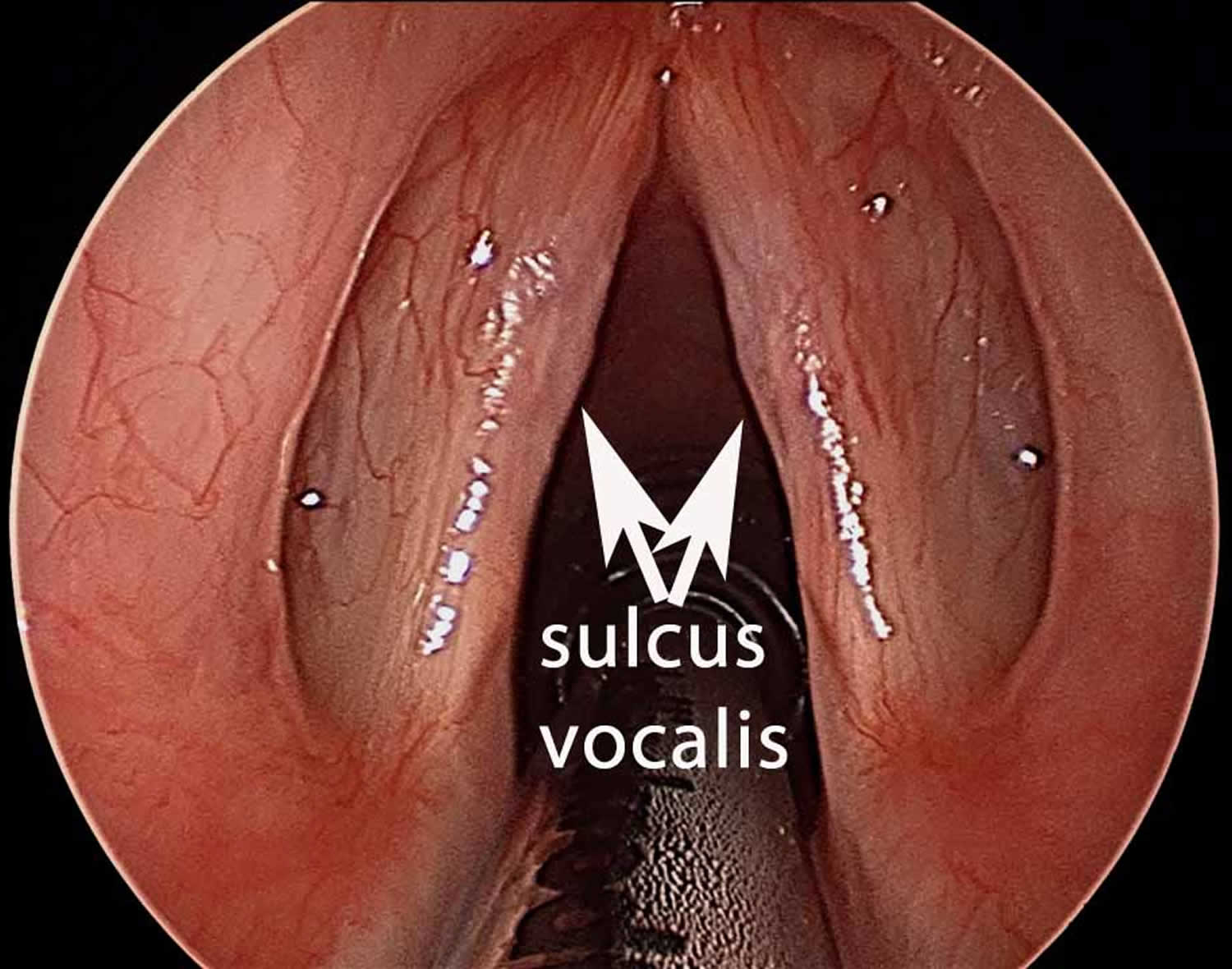

Figure 1. Sulcus vocalis

Footnote: Bilateral sulcus vocalis of vocal folds (pointed by the arrow marks).

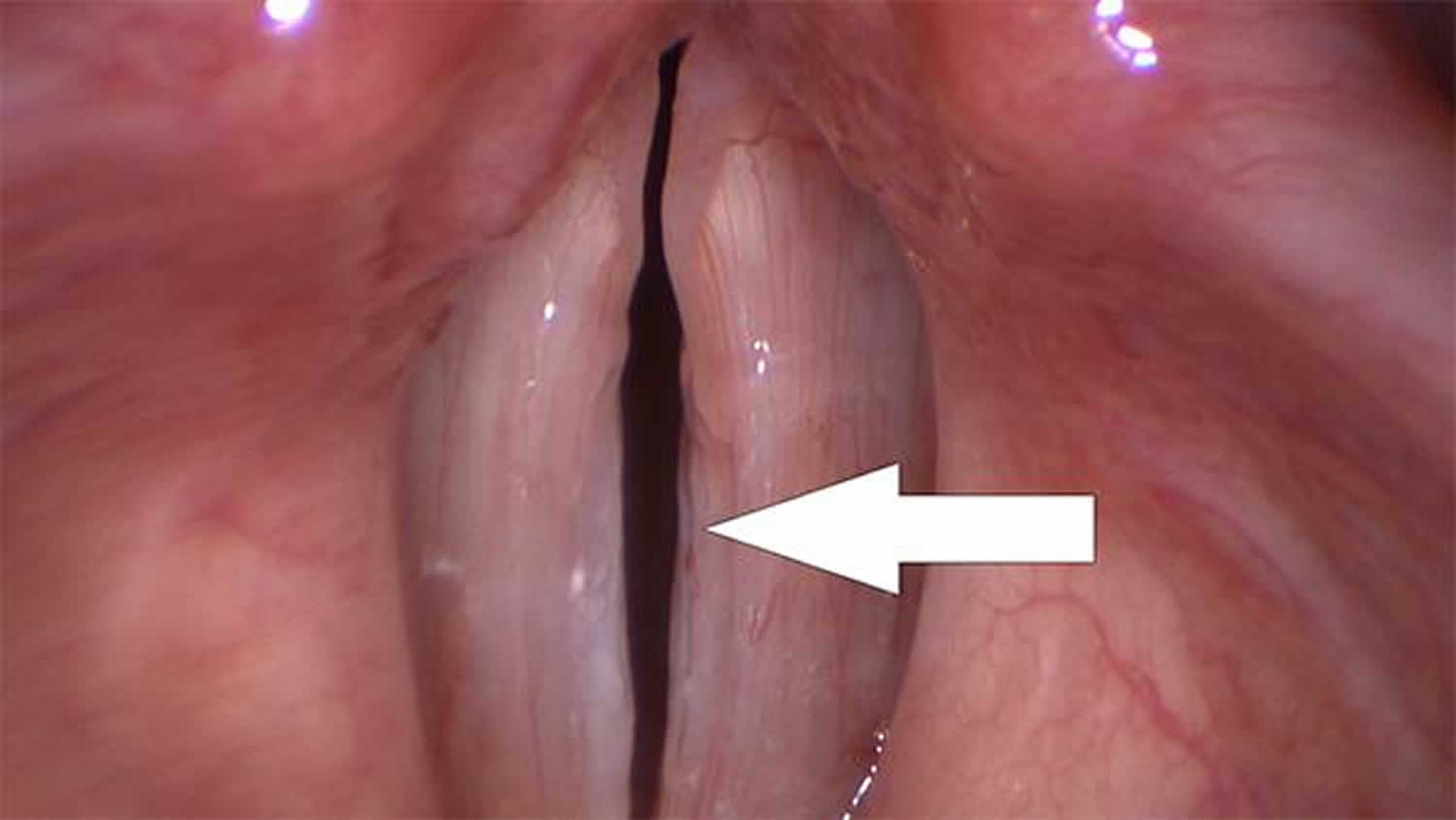

Figure 2. Vocal cord sulcus

Footnote: The subtle groove on the edge of the right vocal fold represents a sulcus vocalis.

Vocal cord anatomy

Awareness of the body-cover principle of vocal fold vibration is essential to the understanding of sulcus vocalis. The vocal fold is composed of a muscle covered by a free mucosal edge that vibrates and can be separated into discrete layers in which various types of pathology may develop. Each layer has distinct mechanical properties and can be differentiated by the concentration of elastin and collagen fibers that run parallel to the leading edge.

Histologically, the vocal fold is a complex structure. The delicate arrangement of extracellular matrix proteins within the lamina propria permits passive movement of the vocal cover over the vocal ligament and muscle, or body. This results in formation of the mucosal wave as air is passed through the glottis as a release of building subglottic pressure. Violation of deeper layers of the lamina propria and vocal ligament, as was once common with stripping procedures, is now known to be associated with scar and sulcus formation.

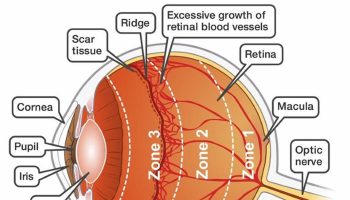

Figure 3. Vocal cord

Sulcus vocalis types

There are three types of sulcus vocalis. Ford et al 10 has classified sulcus vocalis into 3 groups:

- Type 1 Physiologic sulcus vocalis: Physiologic sulcus (type 1) is a longitudinal depression that extends along the superficial layer of lamina propria without actually moving the vocal ligament. In physiologic sulcus, there is preserved vibratory activity and anatomic layer of lamina propria as reported. The voice is Normal.

- Type 2 Sulcus vergeture: Type 2 Sulcus vergeture is a more extensive longitudinal indentation that does not extend into the vocal ligament, involving loss of superficial, intermittent and deep layer of lamina propria. Type 2 sulcus vocalis is considered pathologic.

- Type 2a sulcus vocalis: epithelial invagination along the vocal fold: some dysphonia

- Type 2b sulcus vocalis: epithelial invagination into the vocalis muscle; severe dysphonia

- Type 3 Sulcus vocalis proper: Type 3 Sulcus vocalis proper is a focal pit which extends beyond the vocal ligament into the thyro-arytenoid muscle 11.

Pontes et al 12 propose the following categories:

- Sulcus stria minor—epithelial invagination, whose upper and lower lips usually touch each other;

- Sulcus stria major—spindle-shaped mucosal depression, with a stiffer consistency and adhering to deeper structures, such as the vocal ligament and muscle;

- Pouch-shaped sulcus—lesion that emerges as an invagination, whereby its lips touch each other and the opening leads to a dilated pouch-shaped subepithelial space.

Sulcus vocalis causes

The cause of sulcus vocalis is not widely studied and is poorly understood. Sulcus vocalis may be congenital (present at birth) or secondary to vocal trauma, vocal abuse, infections, laryngoesophageal reflux, degeneration of benign lesions, or surgery 13. In addition, Bouchayer et al 14 proposed a relationship with ruptured congenital epidermoid cysts and also suggested that the disorder may demonstrate familial patterns. Typically, patients with congenital sulci have a lifelong history of disordered voice.

Presence of parallel sulci associated with a mucosal bridge is consistent with ruptured cyst etiology. Surgical causes include overresection of the superficial layer of the lamina propria, resulting in remucosalization over the deficient area and damage to the vocal ligament and deep layers of the lamina propria. Nonsurgical causes include untreated benign lesions, chronic vocal abuse, and repeated intracordal hemorrhage. Microvascular lesions (ie, varices, capillary ectasias) also may result in scarring secondary to hemorrhage and fibrosis.

A retrospective study by Lee et al 15 indicated that epithelial pathology plays a significant role in sulcus vocalis, with the prevalence of parakeratosis, dyskeratosis, and epithelial thickening found to be particularly high in sulcus vocalis. The investigators suggested that epithelial changes cause perilesional inflammation, which in turn produces clinical changes.

A defect in the medial surface of the true vocal fold along the sulcus may produce a glottic gap. More importantly, the cover may fibrose to the vocal ligament and result in a diminished or absent vocal mucosal wave. This decreased pliability restricts the Bernoulli and myoelastic effects, whereby transglottic airflow medializes the leading edge of the vocal fold. The overall effect is usually a higher fundamental frequency with significantly reduced harmonics and harsher voice quality.

Sulcus vocalis symptoms

Patients may experience hoarseness but more often have symptoms and signs of glottal insufficiency, including vocal fatigue, poor volume, and poor projection. However, the voice may be normal with more subtle symptoms (eg, fatigue, decreased vocal range with singing).

On initial interview, the voice may be hoarse and breathy or acceptable, but most patients have an overall decrease in vocal performance.

Examination of the true vocal fold reveals a linear depression or an area of incomplete closure. Videostroboscopy reveals an area of decreased mucosal wave corresponding to the sulcus and more clearly demonstrates the associated incomplete closure.

Sulcus vocalis diagnosis

Patients with symptoms of hoarseness, loss of range, or voice fatigue with no obvious laryngeal pathology need to see a laryngologist for further evaluation, preferably to an otolaryngologist with special interest and training in diagnosis and treatment of voice disorders. Sulcus vocalis is a challenging rare disorder and often is best treated by a subspecialist.

A laryngologist usually employs a team approach to the diagnosis and treatment of voice disorders (eg, speech pathologist, singing voice specialist) and has a variety of specialized endoscopes that allow for detailed examination of the larynx.

Videostroboscopy is an important tool used by the laryngologist. This imaging system is controlled in part by the patient’s vocal pitch, allowing for slow-motion video recording of vocal fold vibration. Examination of the true vocal fold reveals a linear depression or an area of incomplete closure. Videostroboscopy reveals an area of decreased mucosal wave corresponding to the sulcus and more clearly shows associated incomplete closure.

Other diagnostic studies commonly employed by the laryngologist include acoustic and airflow measurements.

- Acoustic analysis reveals some information about vocal production efficiency and voice strength.

- Airflow measurements are useful in gauging vocal support and glottic constriction.

Sulcus vocalis treatment

There are two lines of management of sulcus vocalis: medical (surgical) and non-medical (behavioral modification, counseling and voice therapy) management. Anatomic change in the vocal fold (eg, sulcus vocalis) is difficult to treat medically. Conservative treatment should be exhausted before surgical intervention is considered.

Any intercurrent medical conditions affecting the voice (eg, reflux laryngitis, allergic rhinitis) are evaluated and treated. Prior to considering surgical therapy, all known sources of mechanical trauma are maximally reduced to determine reversibility and hopefully prevent a postoperative recurrence. This is accomplished in part by medical and speech therapy to reduce vocal trauma through improved phonatory technique and vocal hygiene.

The primary goal of speech therapy is to improve vocal efficiency. The method most commonly employed is direct speech therapy. When voice therapy is combined with external measures (eg, amplification) and behavioral alterations (eg, scheduling vocal rest periods), vocal fatigue may dissipate.

Surgery is reserved for unresolving lesions that have resulted in persistent troublesome dysphonia. The main difficulty in surgery involves finding a perfect substitute for the missing superficial lamina propria tissue. Efforts to create a substitute in the laboratory are underway, and may be ready for clinical use in the near future.

Surgical management includes vocal fold medialization which includes intrafold injection and medialization surgery. Intrafold injection includes transoral injection with indirect laryngeal mirror, transoral injection with direct laryngoscopy and transcutaneous injection. The medialisation surgery includes surgical augmentation, medial shift of thyroid cartilage and rotation of arytenoid cartilage 7. However, studies report that the impacts of surgeries in sulcus vocalis are unpredictable and the goal is usually to reduce the glottic leakage. It may also be possible that the post-operative voice would be even worse than the preoperative voice 8.

Voice therapy includes implementing hygienic, symptomatic, psychogenic, physiologic and eclectic approaches. Voice therapy has limited success in clients with sulcus vocalis 9. In general, voice therapy in sulcus vocalis focuses on reducing strain on vocal folds, reducing compensatory voice changes and optimising the voice production subsystems, thereby increasing the vocal efficiency. However, there is a need to systematically document the voice profile of clients with sulcus vocalis in order to understand their voice characteristics and determine the efficacy of voice therapy for such individuals.

Surgical therapy

Patients with sulcus vocalis may complain of vocal insufficiency, loss of quality, or both. When low volume and loss of projection are major complaints, vocal fold medialization of the scarred vocal fold may significantly improve vocal performance while decreasing effort and fatigue 16. However, vocal fold medialization alone may not significantly impact vocal quality. An attempt to reconstitute the lamina propria may be considered for patients who have adequate volume but poor vocal quality 17.

Some support the idea that the strip of sulcus should be completely removed, and that neighboring normal tissues should be drawn in to cover the gap left by the removal. While this procedure is sound in theory, it typically results in scarring, with hoarseness that may be equal to or even worse than that caused by sulcus itself.

Other physicians suggest that the vocal fold cover should be lifted up, and a new tissue should be inserted to keep it apart from deeper tissues. Fat from elsewhere in the body, collagen, and other substances are typically used. Results are inconsistent and somewhat unpredictable, but favorable results have been achieved with this method. It is hoped that the development of bioengineered superficial lamina propria tissue, currently being researched, will improve the results obtained with this approach.

Current opinion holds that placing a biocompatible material between the vocal ligament and cover or within the layers of the lamina propria could compensate for lost tissue and restore sliding movement of the mucosal cover. This additional layer also may prevent fibroblast migration from deeper layers and further scar formation. A thick scar band associated with the sulcus may be removed through a microflap approach. However, this maneuver carries the risk of further fold thinning. The ideal implant material assumes the function of the intermediate layer of the lamina propria, which is composed of elastin, hyaluronic acid, and fibromodulin. Implant material is placed to augment the infraglottics and free edge of the vocal fold. Phonation threshold pressure (ie, amount of pressure required to initiate voice) is decreased by improved closure, increased fold thickness, and lower viscous damping (ie, tissue inertia). Therefore, the ideal implant has low viscosity and resorption and is injectable.

Finally, some surgeons, displeased by the unreliability of these first two approaches, settle for injecting the vocal fold to close the spindle-shaped gap created by sulcus. They and their patients accept that this is only a partial solution, but that it may be the best available option.

Injectable collagen gained interest early because of its ability to soften scar tissue when used in the face. Irradiated cadaveric collagen is readily available in a powder form, which can be reconstituted and injected through a narrow-gauge needle. This can be safely used without sensitivity testing and has a duration of up to 3 years. When normal lamina propria reproduction is the goal of implantation, fat is the available material most similar in viscosity (4 pascal seconds [Pa-s]) to the lamina propria. In contrast, collagen has a much higher viscosity (10 pascal seconds). However, collagen is much easier to inject and is more readily obtained. Furthermore, collagen can be injected transcutaneously in a clinic setting.

Autologous fat probably is the best augmentation material in widespread use 18. More forgiving placement of autologous fat within the larger muscle bed is possible, and longevity has improved through development of viable adipocytes. Archer and Banks demonstrated maintenance of viable adipocytes and bulk for up to 1 year in an animal model.

Fat may be implanted into the vocal fold through an endoscopic approach but may also be implanted through a surgically created window in the thyroid cartilage, or “minithyrotomy” 19. Paniello 20 reported good results in 2 patients treated specifically for sulcus vocalis with this approach.

A study by Karle et al 21 indicated that treatment of sulcus vocalis and vocal fold scars with autologous transplantation of temporalis fascia into the vocal fold can produce good long-term results. The investigators reported that at 6-month follow-up, patients who underwent the procedure experienced a mean reduction in Voice Handicap Index–10 (VHI-10) scores of 8.35, while at an average follow-up of 44 months, VHI-10 scores had decreased by 13.53 from their preoperative values. One complication occurred among the study’s 21 patients, and it was minor and self-limited.

Injectable hyaluronic acid may also have an application in the treatment of patients with sulcus vocalis. Because hyaluronic acid makes up the gel-like space of the superficial lamina propria, replacing it has long been considered the holy grail of therapy for vocal scarring. Although the usefulness of hyaluronic acid is unknown, early reports suggest that maintaining sufficient volume of material in the desired location is problematic. Studies into the use of this material are ongoing.

A study by Hwang et al 22 suggested that pulsed dye lasers can effectively be used to treat sulcus vocalis. Each treatment in the study, which involved 25 patients with the condition, consisted of 60-100 laser pulses (0.75 Joules per pulse) on each vocal fold. The procedures appeared to decrease vocal fold stiffness, improve mucosal wave properties, and reduce dysphonia. Moreover, in most patients, improvement was demonstrated in several postoperative voice analysis indices.

A study by Lee et al 15, which indicated that epithelial pathology plays an important part in sulcus vocalis, suggested that surgical treatment should involve the removal of pathologic epithelium, as a means of treating inflammation.

Sulcus vocalis prognosis

In 2 studies, microsurgical techniques were used on 30 patients with pathologic sulcus. Voice improvement was reported in the majority of subjects using objective measures. Using fat implantation methods, Sataloff et al 23 described voice improvement and limited return of mucosal wave. Most patients can expect significant voice improvement from either technique, but results are not equal to premorbid conditions in most cases. Additionally, insufficient data exists on the longevity of improvement 24.

- Sulcus Vocalis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/866094-overview[↩][↩]

- Rajasudhakar R. Effect of voice therapy in sulcus vocalis: A single case study. S Afr J Commun Disord. 2016;63(1):e1-e5. Published 2016 Nov 30. doi:10.4102/sajcd.v63i1.146 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5843232[↩]

- Nakayama M, Ford CN, Brandenburg JH, Bless DM. Sulcus vocalis in laryngeal cancer: a histopathologic study. Laryngoscope. 1994;104(1 Pt 1):16-24. doi:10.1288/00005537-199401000-00005 https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199401000-00005[↩][↩]

- Sunter AV, Yigit O, Hug GE, Alkan Z, Kocak l, Buyuk Y; Histopathologic Characteristics of Sulcus Vocalis; Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011 Aug;145(2):264-9.[↩]

- Boon D.R., McFarlane S.C., Von Berly S.L., & Zraick R.I (2010). The voice and voice therapy. (8th edn.). Boston, MA: Pearson Publication.[↩]

- Akbulut S, Altintas H, Oguz H. Videolaryngostroboscopy versus microlaryngoscopy for the diagnosis of benign vocal cord lesions: a prospective clinical study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(01):131–136.[↩]

- Calton R.H., & Casper J.K (1990). Understanding voice problems. A physiological perspective for diagnosis and treatment. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, pp. 51–69.[↩][↩]

- Giovanni, A., Chanteret, C. & Lagier, A. Sulcus vocalis: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 264, 337 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0230-8[↩][↩]

- Rubin J.S., & Yanagisawa E (2006). Benign vocal fold pathology through the eyes of the laryngologist In Rubin J.S., Sataloff R.T, & Korovin G.S (Eds.), Diagnosis and treatment of voice disorders. (3rd edn., pp. 209–221). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing Inc.[↩][↩]

- Ford, C. N., Inagi, K., Khidr, A., Bless, D. M., & Gilchrist, K. W. (1996). Sulcus Vocalis: A Rational Analytical Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, 105(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348949610500304[↩]

- Bouchayer M., & Cornut G (2000). Voice disorders of structural orgin In Aronson A.E. & Bless D.M. (Eds.), Clinical voice disorders (2010) (pp. 164–178). New York: Thieme Publishers.[↩]

- Pontes P, Behlau M, Gonçalves I. Alterações estruturais mínimas da laringe (AEM): considerações básicas. Acta AWHO. 1994;13:2–6.[↩]

- Malmstrom E, Hertegard S. Background Factors and Subjective Voice Symptoms in Patients with Acquired Vocal Fold Scarring and Sulcus Vocalis. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2017. 69 (3):125-30.[↩]

- Bouchayer M, Cornut G, Witzig E, et al. Epidermoid cysts, sulci, and mucosal bridges of the true vocal cord: a report of 157 cases. Laryngoscope. 1985 Sep. 95(9 Pt 1):1087-94.[↩]

- Lee A, Sulica L, Aylward A, Scognamiglio T. Sulcus vocalis: a new clinical paradigm based on a re-evaluation of histology. Laryngoscope. 2015 Nov 3.[↩][↩]

- Welham NV, Choi SH, Dailey SH, Ford CN, Jiang JJ, Bless DM. Prospective multi-arm evaluation of surgical treatments for vocal fold scar and pathologic sulcus vocalis. Laryngoscope. 2011 Jun. 121(6):1252-60.[↩]

- Yilmaz T. Sulcus vocalis: excision, primary suture and medialization laryngoplasty: personal experience with 44 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Nov. 269(11):2381-9.[↩]

- Cantarella G, Baracca G, Forti S, Gaffuri M, Mazzola RF. Outcomes of structural fat grafting for paralytic and non-paralytic dysphonia. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011 Jun. 31(3):154-60.[↩]

- Gray SD, Bielamowicz SA, Titze IR, et al. Experimental approaches to vocal fold alteration: introduction to the minithyrotomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999 Jan. 108(1):1-9.[↩]

- Paniello RC, Sulica L, Khosla SM, et al. Clinical experience with Gray’s minithyrotomy procedure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008 Jun. 117(6):437-42.[↩]

- Karle WE, Helman SN, Cooper A, Zhang Y, Pitman MJ. Temporalis Fascia Transplantation for Sulcus Vocalis and Vocal Fold Scar: Long-Term Outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018 Apr. 127 (4):223-8.[↩]

- Hwang CS, Lee HJ, Ha JG, et al. Use of pulsed dye laser in the treatment of sulcus vocalis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 May. 148(5):804-9.[↩]

- Sataloff RT, Spiegel JR, Hawkshaw M, et al. Autologous fat implantation for vocal fold scar: a preliminary report. J Voice. 1997 Jun. 11(2):238-46.[↩]

- Miaskiewicz B, Szkielkowska A, Pilka A, Skarzynski H. Results of surgical treatment in patients with sulcus vocalis. Otolaryngol Pol. 2015. 69 (6):7-14.[↩]