Occupational asthma

Occupational asthma also called work-related asthma, is defined as asthma due to conditions attributable to workplace exposures such as breathing in chemical fumes, gases, dust or other substances on your job and not to causes outside the workplace 1. Occupational asthma can result from exposure to a substance you’re sensitive to causing an allergic or immunological response or to an irritating toxic substance. Like other types of asthma, occupational asthma can cause chest tightness, wheezing and shortness of breath. People with allergies or with a family history of allergies are more likely to develop occupational asthma.

There are two main categories of work-related asthma:

- Occupational asthma – Occupational asthma describes asthma caused by worksite exposures. Occupational asthma can be further divided into two groups:

- Sensitizer-induced asthma – caused by sensitization (reaction) to a substance.

- Irritant-induced asthma also called reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (RADS) which is caused by one specific, high-level exposure.

- Work-exacerbated asthma sometimes known as work-aggravated asthma – Work-exacerbated asthma describes existing asthma that worsens because of worksite exposures to irritants, allergens, or physical conditions (e.g., factors at work may trigger, aggravate, or exacerbate existing asthma).

An estimated 15 percent to 23 percent of new adult asthma cases in the United States are due to occupational exposures. These exposures in the workplace also can worsen pre-existing asthma. Symptoms usually occur while the worker is exposed at work but, in some cases, they develop several hours after the person leaves work and then subside before the worker returns to the job. In later stages of the disease, symptoms may occur away from work after exposure to common lung irritants such as air pollution or dust.

Not all workers will react with an asthmatic response when exposed to substances.

Occupational asthma that is not identified and managed early can get worse. Work-related asthma reduces productivity and quality of life. Asthmatic attacks can be controlled either by ending exposure to the substance, or by medical treatment to manage the asthma symptoms.

Occupational asthma is usually reversible, but permanent lung damage can occur if exposure continues. According to one study, men working in forestry and with metals and women in the service industries (waitresses, cleaners and dental workers) have the highest risk for occupational asthma.

If it’s not correctly diagnosed and you are not protected or able to avoid exposure, occupational asthma can cause permanent lung damage, disability or death.

The most important step of treating asthma is stopping or reducing exposure to the asthma occupational triggers causing symptoms. Otherwise, treatment for occupational asthma is similar to treatment for other types of asthma and generally includes taking medications to reduce symptoms. If you already have asthma, sometimes treatment can help it from becoming worse in the workplace. You should work with your doctor to develop a personal asthma control plan. Asthma is often treated with two general types of medicine:

- Quick-relief rescue inhalers (e.g., albuterol, levalbuterol) to open the airways. People use these medicines to treat asthma attacks or flare-ups.

- Long-term control medicines to reduce inflammation in the airways. People use these medicines to help keep asthma symptoms from occurring. When these medicines are working well, quick relief medicine is not used as much.

Seek immediate medical treatment if your symptoms worsen. Severe asthma attacks can be life-threatening. Signs and symptoms of an asthma attack that needs emergency treatment include:

- Rapid worsening of shortness of breath or wheezing

- No improvement even after using a quick relief inhaler

- Shortness of breath even with minimal activity

Make an appointment to see a doctor if you have breathing problems, such as coughing, wheezing or shortness of breath. Breathing problems may be a sign of asthma, especially if symptoms seem to be getting worse over time or appear to be aggravated by specific triggers or irritants.

What is asthma?

Asthma is an obstructive airway disorder, limiting expiratory airflow. Asthma is both acute and reversible and is characterized by obstruction of airflow due to inflammation, bronchospasm and increased airway secretions. If you have asthma, your airways can become inflamed or swollen and narrowed at times. That makes them very sensitive, and they may react strongly to things that you are allergic to or find irritating. When your airways react, they get narrower and your lungs get less air. You may wheeze, cough, or feel tightness in your chest. These symptoms can range from mild to severe and can happen every day or only once in a while. Certain things can set off or worsen asthma symptoms, such as cold air or the weather or things in the environment, such as dust, chemicals, smoke and pet dander. These are called “asthma triggers”. When you breathe in a trigger, the insides of your airways swell even more. This narrows the space for the air to move in and out of the lungs. The muscles that wrap around your airways also can tighten, making breathing even harder. When that happens, it’s called an asthma flare-up, asthma episode or asthma “attack.”

Asthma is a disease that affects people of all races, ages, sexes, and ethnic groups and often starts during childhood. Sometimes, people have asthma when they are very young and as their lungs develop, the symptoms go away, but it’s possible that it will come back later in life. Sometimes people get asthma for the first time when they are older.

It is estimated that 7% of Americans have asthma.

Research has shown something things that make a person more likely to get asthma.

- Family history: If people in your family have an allergic disease like asthma, hay fever (allergic rhinitis), or eczema, there is a higher chance you will have asthma.

- Stuff inside the air you breathe can make you more likely to get asthma:

- Second-hand smoke: Kids whose mothers smoked while pregnant, who grew up in a smoky house are more likely to get asthma.

- Air pollution indoors and out: research has shown people who live near major highways and other polluted places are more likely to get asthma. Children who grow up in homes with mold or dust are also more likely to get asthma.

- Work environment (occupational asthma): People who work in certain types of jobs can get asthma from the things they work with.

Some examples of asthma triggers are:

- Animal dander and insects

- Chlorine-based cleaning products

- Cigarette smoke

- Cockroach droppings

- Cold air

- Dust from wood, grain, flour, or green coffee beans

- Dust mites

- Gases such as ozone

- Indoor dampness and mold

- Irritant chemicals

- Metal dust

- Physical exertion

- Pollen and plants

- Strong fumes

- Vapors from chemicals (e.g., ammonia, isocyanates, and solvents)

- Wood smoke

How long does occupational asthma take to develop?

There is no fixed period of time in which asthma can develop. Asthma as a disease may develop from a few weeks to many years after the initial exposure. Analysis of the respiratory responses of sensitized workers has established three basic patterns of asthmatic attacks, as follows:

- Immediate – typically develops within minutes of exposure and is at its worst after approximately 20 minutes; recovery takes about 2 hours.

- Late – can occur in different forms. It usually starts several hours after exposure and is at its worst after about 4 to 8 hours with recovery within 24 hours. However, it can start 1 hour after exposure with recovery in 3 to 4 hours. In some cases, it may start at night, with a tendency to recur at the same time for a few nights following a single exposure.

- Dual or Combined – is the occurrence of both immediate and late types of asthma.

Symptoms for work-related asthma tend to get better on weekends, vacations, or other times when away from work. However, in some cases, symptoms do not improve until an extended time away from the exposure or trigger.

Work-related asthma can be diagnosed by your doctor. Tell your doctor about work exposures and possible asthma triggers, including your job, tasks, and the materials you use. Also consider logging when and where your symptoms occur to help determine any patterns. Your doctor will ask you questions about your symptoms and will conduct a physical examination. The doctor might also order one or more of the following tests:

- Breathing tests (e.g., peak flow readings and spirometry)

- Allergy tests such as skin or blood tests

If your doctor is concerned about something other than asthma, he/she might order other tests such as x-rays or imaging tests.

Occupational asthma causes

Work-related asthma is asthma triggered by an exposure at work. Many asthma triggers can be found in the workplace. Over 300 known or suspected substances in the workplace can cause or worsen asthma. Avoiding triggers can prevent asthma from getting worse.

Workplace substances as possible causes of occupational asthma include:

- Animal substances, such as proteins found in dander, hair, scales, fur, saliva and body wastes.

- Chemicals used to make paints, varnishes, adhesives, laminates and soldering resin. Other examples include chemicals used to make insulation, packaging materials, and foam mattresses and upholstery.

- Enzymes used in detergents and flour conditioners.

- Metals, particularly platinum, chromium and nickel sulfate.

- Plant substances, including proteins found in natural rubber latex, flour, cereals, cotton, flax, hemp, rye, wheat and papain — a digestive enzyme derived from papaya.

- Respiratory irritants, such as chlorine gas, sulfur dioxide and smoke.

Asthma symptoms start when your lungs become irritated (inflamed). Inflammation causes several reactions that restrict the airways, making breathing difficult. With occupational asthma, lung inflammation may be triggered by an allergic response to a substance, which usually develops over time. Alternatively, inhaling fumes from a lung irritant, such as chlorine, can trigger immediate asthma symptoms in the absence of allergy.

Table 1. Causes of occupational asthma – Grains, flours, plants and gums

| Occupation | Agent |

|---|---|

| Bakers, millers, cooks | Wheat, flours, grains, nuts, eggs, spices, additives. Also: moulds, mites, crustacea, etc. |

| Chemists, coffee bean baggers and handlers, gardeners, millers, oil industry workers, farmers | Castor beans |

| Cigarette factory workers | Tobacco dust |

| Drug manufacturers, mold makers in sweet factories, printers | Gum acacia |

| Farmers, grain handlers | Grain dust |

| Gum manufacturers, sweet makers | Gum tragacanth |

| Strawberry growers | Strawberry pollen |

| Tea sifters and packers | Tea dust |

| Tobacco farmers | Tobacco leaf |

Table 2. Causes of occupational asthma – Animals, animal substances, insects and fungi

| Occupation | Agent |

|---|---|

| Bird fanciers | Avian proteins |

| Cosmetic manufacturers | Carmine |

| Entomologists | Moths, butterflies, cockroaches |

| Feather pluckers | Feathers |

| Field contact workers | Crickets |

| Fish bait breeders | Bee moths |

| Flour mill workers, bakers, farm workers, grain handlers | Grain storage mites, alternaria, aspergillus |

| Laboratory workers | Locusts, cockroaches, grain weevils, rats, mice, guinea pigs, rabbits |

| Mushroom cultivators | Mushroom spores |

| Oyster farmers | Hoya |

| Pea sorters | Mexican bean weevils |

| Pigeon breeders | Pigeons |

| Poultry workers | Chickens |

| Prawn processors | Prawns |

| Silkworm sericulturers | Silkworms |

| Veterinary clinic, animal breeders | Secretions from saliva, feces, urine and skin from various animals (cats, dogs, rabbits, horses, birds, rodents, etc.) |

| Woollen industry workers | Wool |

| Zoological museum curators | Beetles |

Table 3. Causes of occupational asthma – Chemicals and Materials

| Occupation | Agent |

|---|---|

| Adhesive industry | Various agents including amines, acrylates, aldehydes, styrene, etc. |

| Aircraft fitters | Triethyltetramine |

| Aluminum cable solderers | Aminoethylethanolamine |

| Aluminum pot room workers | Fluorine |

| Autobody workers | Acrylates (resins, glues, sealants, adhesives), metals, amines, anhydrides, acrylates, urethanes, polyvinyl chloride, etc. |

| Brewery workers | Chloramine-T, mould |

| Chemical plant workers, pulp mill workers | Chlorine, formaldehyde, acid/alkaline gas, vapours, aerosols, sulphites |

| Dentists, dental workers | Acrylates, latex |

| Dye weighers | Levafix brilliant yellow, drimarene brilliant yellow and blue, cibachrome brilliant scarlet |

| Electronics workers | Colophony |

| Epoxy resin manufacturers | Tetrachlorophthalic anhydride |

| Foundry mold makers | Furan-based resin binder systems |

| Fur dyers | Para-phenylenediamine |

| Hairdressers | Persulphate salts, henna, formaldehyde, etc. |

| Health care workers | Glutaraldehyde, latex, certain drugs, sterilizing agents, disinfectants, etc. |

| Janitor, service, cleaning | Chloramines, amines, pine products, some fungicides and disinfectants, acetic acid, etc. Also: mixing chlorine bleach with ammonia |

| Laboratory workers, nurses, phenolic resin molders | Formalin/formaldehyde, detergent, enzymes |

| Meat wrappers | Polyvinyl chloride vapour |

| Paint manufacturers, plastic molders, tool setters, Paint sprayers | Phthalic anhydride, latex, diisocyanates, amines, chromium, acrylates, formaldehyde, styrene, dimethylethanolamine etc. |

| Photographic workers, shellac manufacturers | Ethylenediamine |

| Refrigeration industry workers | CFCs |

| Solderers | Polyether alcohol, polypropylene glycol |

Table 4. Causes of occupational asthma – Isocyanates and metals

| Occupation | Agent |

|---|---|

| Boat builders, foam manufacturers, office workers, plastics factory workers, refrigerator manufacturers, TDI manufacturers/users, printers, laminators, tinners, toy makers | Toluene diisocyanate |

| Boiler cleaners, gas turbine cleaners | Vanadium |

| Car sprayers | Hexamethylene diisocyanate |

| Cement workers | Potassium dichromate |

| Chrome platers, chrome polishers | Sodium bichromate, chromic acid, potassium chromate |

| Machinist, mechanic, metal workers, fabricating | Cobalt, vanadium, chromium, platinum, nickel, metal working fluids, amines |

| Nickel platers | Nickel sulphate |

| Platinum chemists | Chloroplatinic acid |

| Platinum refiners | Platinum salts |

| Polyurethane foam manufacturers, printers, laminators | Diphenylmethane diisocyanate |

| Rubber workers | Naphthalene diisocyanate |

| Tungsten carbide grinders | Cobalt |

| Welders | Stainless steel fumes |

Table 5. Causes of occupational asthma – Drugs and enzymes

| Occupation | Agent |

|---|---|

| Ampicillin manufacturers | Phenylglycine acid chloride |

| Detergent manufacturers | Bacillus subtilis |

| Enzyme manufacturers | Fungal alpha-amylase |

| Food technologists, laboratory workers | Papain |

| Pharmacists | Gentian powder, flaviastase |

| Pharmaceutical workers | Methyldopa, salbutamol, dichloramine, piperazine dihydrochloride, spiramycin, penicillins, sulphathiazole, sulphonechloramides, chloramine-T, phosdrin, pancreatic extracts |

| Poultry workers | Amprolium hydrochloride |

| Process workers, plastic polymer production workers | Trypsin, bromelin |

Table 6. Causes of occupational asthma – Woods

| Occupation | Agent |

|---|---|

| Carpenters, timber millers, woodworkers, sawmill workers, pattern makers, wood finishers, wood machinists | Western red cedar, cedar of Lebanon, iroko, California redwood, ramin, African zebrawood, ash, African maple, Australian blackwood, beech, box tree, Brazilian walnut, ebony, Mansonia, oak, mahogany, abiruana, spruce, Cocabolla, Kejaat, etc. Also: insects, mould, lacquers, etc. |

Risk factors for occupational asthma

Some workplace conditions seem to increase the likelihood that workers will develop asthma, but their importance is not fully known. Factors such as the properties of the chemicals, and the amount and duration of exposure are important. However, because only a fraction of exposed workers are affected, factors unique to individual workers can also be important. Such factors include the ability of some people to produce abnormal amounts of IgE antibodies. The contribution of cigarette smoking to asthma is not known. However, smokers are more likely than nonsmokers to develop respiratory problems in general.

The intensity of your exposure increases your risk of developing occupational asthma. In addition, you will have increased risk if:

- You have existing allergies or asthma. Although this can increase your risk, many people who have allergies or asthma do jobs that expose them to lung irritants and never have symptoms.

- Allergies or asthma runs in your family. Your parents may pass down a genetic predisposition to asthma.

- You work around known asthma triggers. Some substances are known to be lung irritants and asthma triggers.

- You smoke. Smoking increases your risk of developing asthma if you are exposed to certain types of irritants.

High-risk occupations

It’s possible to develop occupational asthma in almost any workplace. But your risk is higher if you work in certain occupations. Some of the riskiest jobs and the asthma-producing substances associated with them include the following:

- Adhesive handlers: Chemicals

- Animal handlers, veterinarians: Animal proteins

- Animal health:

- Anesthetic agents

- Animal proteins (from hair/fur, saliva, urine, and dander)

- Biocides (gluteraldehydes and chlorhexidine)

- Cleaning products

- Drugs (antibiotics)

- Endotoxin

- Enzymes

- Latex

- Pollen

- Bakers, millers, farmers: Cereal grains

- Carpet makers: Vegetable gums

- Cleaning services:

- Acetic acid

- Acids

- Ammonia (ammonium hydroxide)

- Biocides

- Bleach (sodium hypochlorite)

- Chloramines

- Formaldehyde

- Glutaraldehyde

- Quaternary ammonium compounds (e.g., benzalkonium chloride)

- Spray products

- Cosmetology:

- Acrylic monomers

- Bleaching agents

- Biocides

- Formaldehyde

- Hair dyes

- Henna

- Latex

- Persulfates

- Metal workers: Cobalt, nickel

- Farming and Food Production:

- Cereals and grains

- Egg protein

- Endotoxin

- Enzymes

- Fish and shellfish

- Green coffee beans/dust

- Insects

- Milk protein

- Plants

- Plant products (natural rubber latex)

- Plant proteins (grain, wheat, coffee beans/dust, tea, flours)

- Pollen

- Food production workers: Milk powder, egg powder

- Forest workers, carpenters, cabinetmakers: Wood dust

- Health care workers:

- Latex and chemicals

- Acrylic monomers

- Aerosolized medications (e.g., pentamidine, ribavirin)

- Anesthetic agents

- Biocides (e.g., gluteraldehydes and chlorhexidine)

- Cleaning products (e.g., quaternary ammonium compounds)

- Drugs (antibiotics)

- Enzymes

- Latex

- Metal in dental alloys

- Orthopedic adhesives (methacrylates)

- Psyllium

- Industrial, Manufacturing, or Construction:

- Acid anhydrides (epoxy resin, dye)

- Acrylic monomers (adhesives)

- Aliphatic amines (e.g., ethylenediamines and ethanolamines)

- Complex platinum salts

- Diisocyanates (e.g., polyurethane and plastic production, spray painting, foamcoating manufacturing)

- Enzymes (e.g., amlyases, lipases, proteases)

- Metal dusts

- Metal salts

- Metalworking fluid

- Western red cedar

- Wood dusts or barks

- Laboratory:

- Animal proteins (from hair/fur, saliva, urine, and dander)

- Enzymes

- Fungi

- Latex

- Office and Educational:

- Indoor dampness and mold (indoor environmental quality)

- Vegetable gums (printer ink)

- Pharmaceutical workers, bakers: Drugs, enzymes

- Seafood processors: Herring, snow crab

- Spray painters, insulation installers, plastics and foam industry workers, welders, metalworkers, chemical manufacturers, shellac handlers: Chemicals

- Textile workers: Dyes, plastics

- Users of plastics or epoxy resins, chemical manufacturers: Chemicals.

Occupational asthma pathophysiology

The symptoms and signs of work-related asthma are generally the same as those of non-work-related asthma. Work-related asthma is defined by causation or worsening from exposure to occupational environmental sensitizers, irritants, or physical conditions. Regardless of the asthma trigger type, the response is characterized by inflammation, edema, bronchoconstriction, and buildup of mucus in the airways, leading to coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath.

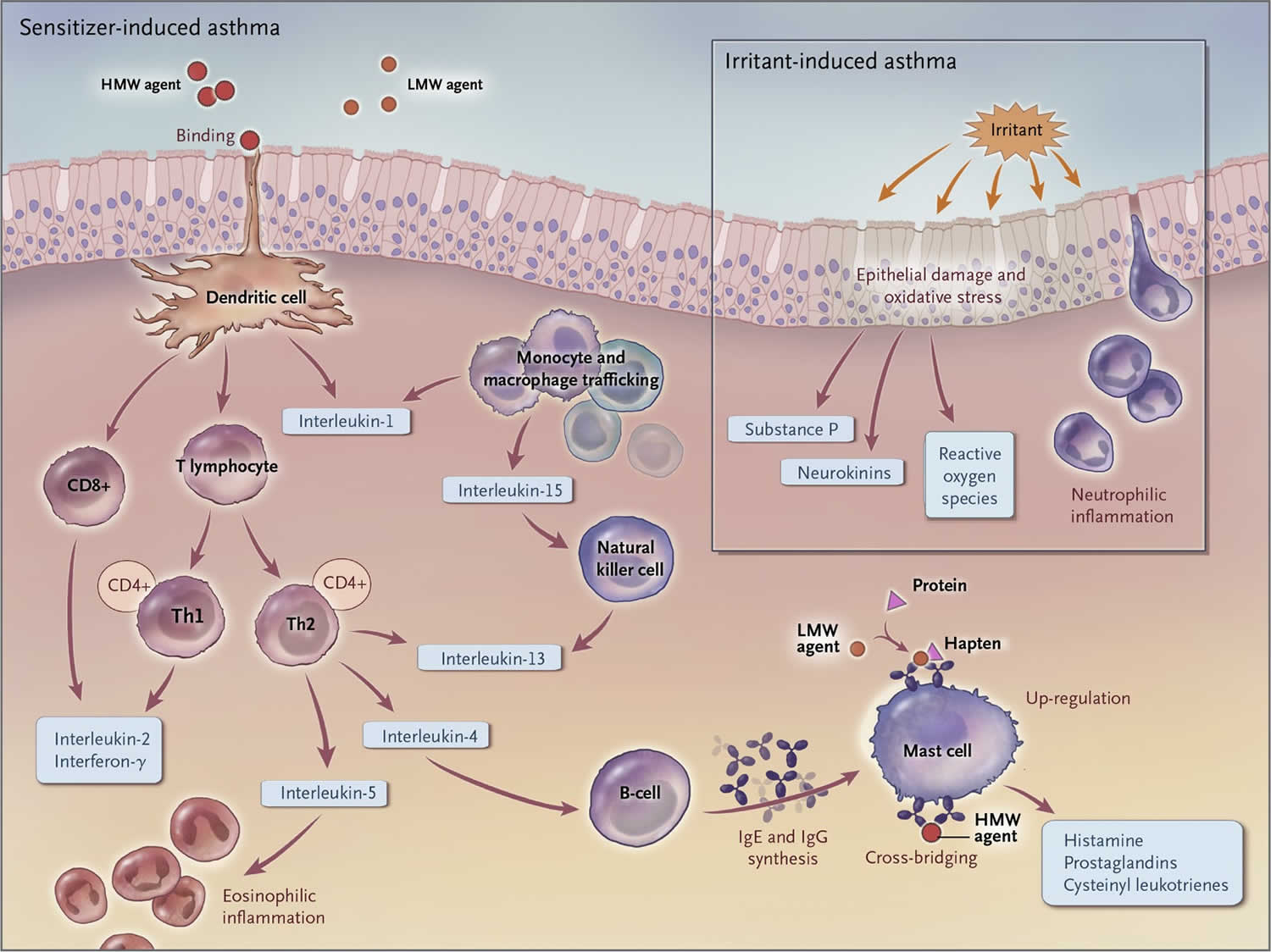

The pathophysiological mechanisms of occupational asthma appear to be similar to those of non–work-related asthma, including an IgE-dependent mechanism associated with high-molecular-weight sensitizing agents and some low-molecular-weight sensitizers. However, for asthma induced by other low-molecular-weight sensitizers, such as diisocyanates, and for irritant-induced asthma, the mechanisms are incompletely delineated. Nevertheless, occupational asthma constitutes an important model for an improved understanding of both extrinsic and intrinsic factors in non–work-related asthma. Mechanisms involved in sensitizer-induced asthma and irritant-induced asthma are shown schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Occupational asthma pathophysiology (mechanisms Involved in Sensitizer-Induced Asthma and Irritant-Induced Asthma)

Footnote: High-molecular-weight (HMW) agents act as complete antigens and induce the production of specific IgE antibodies, whereas the low-molecular-weight (LMW) agents to which workers are exposed that induce specific IgE antibodies probably act as haptens and bind with proteins to form functional antigens. Histamine, prostaglandins, and cysteinyl leukotrienes are released by mast cells after IgE cross-bridging by the antigen. After antigen presentation by dendritic cells, T lymphocytes can differentiate into several subtypes of effector cells. Antigen-activated CD4+ cells can differentiate into cells with distinct functional properties conferred by the pattern of cytokines they secrete. Type 1 helper T (Th1) cells produce interferon-γ and interleukin-2. Type 2 helper T (Th2) cells release cytokines such as interleukin-4, -5, and -13; activate B cells; and promote IgE synthesis, recruitment of mast cells, and eosinophilia. CD8+ cells also release interleukin-2 and interferon-γ and correlate with increased disease severity and eosinophilic inflammation. Innate natural killer cells may also release interleukin-13 in response to products of cell damage. There is evidence that some LMW agents, such as diisocyanates, can stimulate human innate immune responses by up-regulating the immune pattern-recognition receptor of monocytes and increasing chemokines that regulate monocyte and macrophage trafficking (e.g., macrophage migration inhibitory factor and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1). Further interleukin release includes interleukin-1 and -15. Injury to the airway epithelium is likely to play a central role in the pathogenesis of irritant-induced asthma. Oxidative stress is likely to be one of the mechanisms causing the epithelial damage. Inhalation of irritants is likely to induce the release of reactive oxygen species by the epithelium. Furthermore, there may be an increased release of neuropeptides from the neuronal terminals, leading to neurogenic inflammation with release of substance P and neurokinins.

[Source 2 ]Sensitizer induced asthma

Sometimes, the body can develop a sensitization (an allergic-type) reaction when it is exposed continuously to a substance. Sensitizers are agents that initiate an allergic (immunologic) response. There is typically a latency period of at least a few months between first exposure and becoming sensitized. Sensitizers are divided into high-molecular weight and low-molecular weight agents:

- High-molecular-weight agents: (e.g., cereals, coffee beans, enzymes, flour, grain dust, plant proteins, seafood, latex, wood dust) stimulate the production of specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. During re-exposure, the agent cross-links specific antibodies on mast cells and activates them to release inflammatory mediators leading to asthma symptoms.

- Low-molecular-weight agents: (e.g., acrylates, anhydrides, diisocyanates, dyes, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, metals, persulfates) are incomplete antigens, called haptens, that combine with a protein to produce a sensitizing agent.

Particularly for high-molecular weight triggers, the inflammatory process activates nitric oxide synthase in the epithelial cells, resulting in release of nitric oxide 3.

The process is usually not immediate; it evolves over a period of time and involves the body’s immune system. A complex defense system protects the body from harm caused by foreign substances or microbes. Among the most important elements of the defense mechanism are special proteins called “antibodies.” Antibodies are produced when the human body contacts an alien substance or microbe. The role of the antibodies is to react with substances or microbes and destroy them. Antibodies are often very selective, acting only on one particular substance or type of microbe.

But antibodies can also respond in a wrong way and cause disorders such as asthma. After a period of exposure to a substance, either natural or synthetic, a worker may start producing too many of the antibodies called “immunoglobulin E” (IgE). These antibodies attach to specific cells in the lung in a process known as “sensitization.” The sensitization may not show any symptoms of disease, or it may be associated with skin rashes (urticaria), hay fever-like symptoms, or a combination of these symptoms. When re-exposure occurs, the lung cells with attached IgE antibodies react with the substance. This reaction results in the release of chemicals such as “leukotrienes” that are made in the body. Leukotrienes provoke the contraction of some muscles in the airways. This action causes the narrowing of air passages which is characteristic of asthma. Reactive Airways Dysfunction Syndrome (RADS) may also appear with lower-level exposure to an irritant over a prolonged period.

Irritant induced asthma

In this case, the disease is caused by the direct irritating effect of certain substances on the airways. This type of asthma is called Reactive Airways Dysfunction Syndrome (RADS).

RADS can appear after an acute, single exposure to high level of irritating agents (e.g., chlorine, anhydrous ammonia and smoke). There is no latency period. The symptoms develop soon after the exposure, usually within 24 hours, and may reappear after months or years, when the person is re-exposed to the irritants.

- Induce a non-allergic response and include gases, fumes, vapors, and aerosols.

- Non-allergen-induced asthma pathophysiology is less understood.

Physical conditions

- Exposure to cold air and physical exertion.

- Cooling or warming of the airway is thought to lead to bronchoconstriction.

Occupational asthma prevention

The best way to prevent occupational asthma is for workplaces to control the workers’ level of exposure to chemicals and other substances that may be sensitizers or irritants. Such measures can include implementing better control methods to prevent exposures, using less harmful substances and providing personal protective equipment (PPE) for workers.

Allergen and Irritant Avoidance

- Reduce occupational and environmental exposures to allergens, irritants, and physical conditions known to worsen asthma symptoms.

- If relevant, initiate a smoking cessation program. Smoking has been associated with difficulty maintaining adequate asthma control.

- Consider referral to a pulmonary, allergy, or occupational medicine specialist for further testing and identification of work-related exposures.

Work Modification or Restrictions

- Exposure cessation is the optimal approach, but exposure reduction through the use of workplace controls may be benefit some workers with work-related asthma.

- For some employees, an individualized management plan (such as assigning an affected employee to a different work location or site away from the exposures or triggers) is required, depending upon medical findings and response to allergen and irritant reduction.

- A short medical removal period can assist with diagnosing patients with suspected work-related asthma. During this period away from work, improvements in peak expiratory flow support an occupational cause.

Although you may rely on medications to relieve symptoms and control inflammation associated with occupational asthma, you can do several things on your own to maintain overall health and lessen the possibility of attacks:

- If you smoke, quit. In addition to all its other health benefits, being smoke-free may help prevent or lessen symptoms of occupational asthma.

- Get a flu vaccination. This can help prevent illness.

- Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and other medications that may make symptoms worse.

- Lose weight. For people who are obese, losing weight can help improve symptoms and lung function.

If you are in the United States and you have a job in a high-risk profession, your company has legal responsibilities to help protect you from hazardous chemicals. Under guidelines established by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), your employer is required to do the following:

- Inform you if you’ll be working with any hazardous chemicals.

- Train you how to safely handle these chemicals.

- Train you how to respond to an emergency, such as a chemical spill.

- Provide protective gear, such as masks and respirators.

- Offer additional training if a new chemical is introduced to your workplace.

Under OSHA guidelines, your employer is required to keep a material safety data sheet (MSDS) for each hazardous chemical used in your workplace. This is a document that must be submitted by the chemical’s manufacturer to your employer. You have a legal right to see and copy such documents. If you suspect you’re allergic to a certain substance, show the MSDS to your doctor.

While at work, be alert for unsafe and unhealthy working conditions and report them to your supervisor. If necessary, call OSHA at 800-321-OSHA (800-321-6742) and ask for an on-site inspection. You can do this so that your name won’t be revealed to your employer.

Occupational asthma symptoms

Occupational asthma symptoms are similar to those caused by other types of asthma. Signs and symptoms of asthma may include:

- Wheezing, sometimes just at night

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Chest tightness

Other possible accompanying signs and symptoms may include:

- Runny nose

- Nasal congestion

- Eye irritation and tearing

Symptoms of work-related asthma can occur at work in response to an exposure or might be delayed, occurring several hours after work, such as in the evening.

Symptoms of severe work-related asthma might not improve enough away from work for a work-related pattern to be evident.

Occupational asthma symptoms depend on the substance you’re exposed to, how long and how often you’re exposed, and other factors. Your symptoms may:

- Get worse as the workweek progresses, go away during weekends and vacations, and recur when you return to work.

- Occur both at work and away from work.

- Start as soon as you’re exposed to an asthma-inducing substance at work or only after a period of regular exposure to the substance.

- Continue after exposure is stopped. The longer you’re exposed to the asthma-causing substance, the more likely you’ll have long-lasting or permanent asthma symptoms.

Asthma symptoms can come and go, and some workers might not have all symptoms. Workers can get work-related asthma even when using personal protective equipment such as respirators or face masks. Sometimes, these breathing problems start at work and continue even after the worker leaves work and exposure has stopped.

Occupational asthma complications

The longer you’re exposed to a substance that causes occupational asthma, the worse your symptoms may become — and the longer it will take for them to improve once you end your exposure to the irritant. In some cases, exposure to airborne asthma triggers can cause permanent lung changes, resulting in disability or death.

Occupational asthma diagnosis

Diagnosing occupational asthma is similar to diagnosing other types of asthma. However, your doctor will also try to identify whether a workplace substance is causing your symptoms and what it may be.

Examples of occupational history questions to ask working patients with respiratory symptoms include:

- What kind of work do you do?

- What type of industry do you work in?

- Are others at work experiencing similar symptoms?

- Are you now or have you previously been exposed to dust, fumes, or chemicals at your workplace?

- Are your symptoms worse at work?

- Are your respiratory symptoms better or worse when away from work, such as on weekends or vacation?

- Do you think your health problems are related to your work?

- Did the symptoms start as an adult, or when you changed jobs?

An asthma diagnosis needs to be confirmed with lung (pulmonary) function tests and an allergy skin prick test. Your doctor may order blood tests, X-rays or other tests to rule out a cause other than occupational asthma.

Some medical conditions can make asthma worse. In some cases, other tests are needed to evaluate for gastroesophogeal reflux and rhinosinusitis.

Testing your lung function

Your doctor may ask you to perform lung function tests. These include:

- Spirometry. This noninvasive test, which measures how well you breathe, is the preferred test for diagnosing asthma. During this 10- to 15-minute test, you take deep breaths and forcefully exhale into a hose connected to a machine called a spirometer. If certain key measurements are below normal for a person of your age and sex, your airways may be blocked by inflammation — a key sign of asthma. Your doctor has you inhale a bronchodilator drug used in asthma treatment, then retake the spirometry test. If your measurements improve significantly, it’s likely you have asthma.

- Peak flow measurement. Your doctor may ask you to carry a small hand-held device that measures how fast you can force air out of your lungs (peak flow meter). The slower you are able to exhale, the worse your condition. You’ll likely be asked to use your peak flow meter at selected intervals during working and nonworking hours. If your breathing improves significantly when you’re away from work, you may have occupational asthma.

Tests for causes of occupational asthma

Your doctor may do tests to see whether you have a reaction to specific substances. These include:

- Allergy skin tests. Doctors will prick your skin with purified allergy extracts and observe your skin for signs of an allergic reaction. These tests can’t be used to diagnose sensitivities to chemicals but may be useful in evaluating sensitivity to animal dander, mold, dust mites and latex.

- Challenge test. You inhale an aerosol containing a small amount of a suspected chemical to see if it triggers a reaction. Doctors test your lung function before and after the aerosol is given to see whether it affects your ability to breathe.

- Serologic testing to measure IgE antibodies for specific allergens.

Occupational asthma treatment

Avoiding the workplace substance or asthma trigger that causes your symptoms is critical. However, once you become sensitive to a substance, tiny amounts may trigger asthma symptoms, even if you wear a mask or respirator.

The goal of treatment is to prevent symptoms and stop an asthma attack in progress. You may need medications for successful treatment. The same medication guidelines are used to treat both occupational and nonoccupational asthma.

The right medication for you depends on a number of things, including your age, symptoms, asthma triggers and what seems to work best to keep your asthma under control.

Occupational asthma medications

Quick-relief, short-term medications

- Short-acting beta agonists. These medications ease symptoms during an asthma attack.

- Oral and intravenous corticosteroids. These relieve airway inflammation for severe asthma. Long-term, they cause serious side effects.

If you find you need to use a quick-relief inhaler more often than your doctor recommends, you may need to adjust your long-term control medication.

Long-term control medications

- Inhaled corticosteroids. Inhaled corticosteroids reduce inflammation and have a relatively low risk of side effects.

- Leukotriene modifiers. These controller medications are alternatives to corticosteroids.

- Long-acting beta agonists (LABAs). LABAs open the airways and reduce inflammation. For asthma, LABAs generally should only be taken in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid.

- Combination inhalers. These medications contain an LABA and a corticosteroid.

Also, if your asthma is triggered or worsened by allergies, you may benefit from allergy treatment. Allergy treatments include oral and nasal spray antihistamines and decongestants.

Alternative medicine

While many people claim alternative remedies reduce asthma symptoms, in most cases more research is needed to see if they work and if they have possible side effects, especially in people with allergies and asthma. A number of alternative treatments have been tried for asthma, but there’s no clear, proven benefit from treatments such as:

- Breathing techniques. These include structured breathing programs such as the Buteyko method, the Papworth method, lung-muscle training and yoga breathing exercises (pranayama). While these techniques may help improve quality of life, they have not proved to improve asthma symptoms.

- Acupuncture. This technique has roots in traditional Chinese medicine. It involves placing very thin needles at strategic points on your body. Acupuncture is safe and generally painless, but evidence for its use in asthma is inconclusive.

- Malo JL, Vandenplas O. Definitions and classification of work-related asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2011;31:645-662[↩]

- Occupational Asthma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:640-649 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1301758 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1301758[↩]

- An Official ATS Clinical Practice Guideline:Interpretation of Exhaled Nitric Oxide Levels (FENO) for Clinical Applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 184. pp 602–615, 2011 https://www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/allergy-asthma/feno-document.pdf[↩]