Malakoplakia

Malakoplakia also known as Von Hansemann’s disease, is a rare chronic granulomatous inflammatory tumor that occurs most frequently in immunocompromised patients affecting any organs in the body, but predominantly the genitourinary tract with specific predilection for the urinary bladder, the kidney and less often other internal sites (e.g., gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, lungs, female genital tract) 1. There have been rare reports of malakoplakia skin involvement and even rarer cases affecting the tongue. Wielenberg et al. 2 in a review of 153 cases, found 89 cases (58%) that involved the urinary tract, out of which 63 (40%) occurred in the urinary bladder. The first description of malakoplakia outside the urinary tract was in 1958 3. There are now accumulating reports of malakoplakia occurring in a wide variety of organs other than the urinary tract, most commonly in the gastrointestinal system, retroperitoneum and less common in lungs, bones, mesenteric lymphatic nodules, medium ear, larynx, palatine tonsil, parotid gland, temporal bone, neck and tongue. Lymph node involvement in malakoplakia has been reported as a regional spread from malakoplakia of bladder 4 and pancreas 5. Concurrent involvement of lymph node by malakoplakia has also been described in case of colonic 6 and prostate adenocarcinoma 7.

Malakoplakia is seen predominantly in males except in genitourinary tract which has a female preponderance 8. The age of presentation varies between 6 weeks of life and 85 years, being more frequent in adults than in children. Usually, malakoplakia affects patients of age more than 50 years, debilitated and immunosuppressed patients. Malakoplakia is usually associated with a chronic bacterial infection 9. Nearly, 90% of the patients have coliform urine infections and 40% have autoimmune diseases or some type of immunodeficiency 8.

Malakoplakia is probably caused an abnormal immune reaction to a localized bacterial infection, most commonly a defective intracellular killing of Escherischia coli (E. coli) by macrophages 10. Other bacteria reported causing malaplakia include Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Rhodococcus equi. The underlying abnormality appears to be defective macrophage lysosomal digestion of phagocytosed bacteria, particularly coliforms. Malakoplakia is characterized by the presence of foamy macrophages with distinctive basophilic inclusions called Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, which are pathognomonic of malakoplakia 1. These are 5-10 μm in diameter and found both as extracellular and intracellular inclusions. They are Gram negative, positive for Periodic Acid Schiff, von Kossa, and Perls’ stain 11.

Malakoplakia is difficult to diagnose from the symptoms alone because the presentation varies according to the organ involved 11. Malakoplakia can even mimic cancer and hence correct diagnosis is required for adequate management of the patient. So far only histopathological examinations have revealed definitive diagnosis.

Malakoplakia is generally considered a chronic, self-limiting inflammatory disease that may undergo spontaneous regression but, depending on the underlying process and organ involved, may be associated with significant risk of mortality 5. Management of malakoplakia requires a combination of surgical and medical therapies. Antimicrobials such as fluoroquinolones are particularly effective because of their intramacrophagic penetration, and ciprofloxacin is the drug of choice 12. Macrophage function can also be improved by the use of a cholinergic agent, such as bethanechol chloride. Surgical management is curative in almost all these cases as there is no reported evidence of malignant potential.

Malakoplakia skin

Malakoplakia of the skin has been reported in association with:

- Immunosuppression, such as organ transplant recipients

- Internal organ involvement with extension to the skin following surgery.

Malakoplakia of the tongue is very rare. It has presented in children and throughout adult life to extreme old age. Males appear to be more commonly affected than females. Unlike malakoplakia of the skin, there has been no apparent association with immunosuppression nor involvement of internal organs.

Malakoplakia is probably an abnormal response to bacterial infection, usually E. coli. There have been a number of theories proposed to explain this. A reduction in the messenger chemical, cyclic guanine monophosphate, has been noted within the tissue macrophages (immune cells). These cells fail to kill bacteria, with the formation of von Hansemann cells and the development of an abnormal inflammatory reaction.

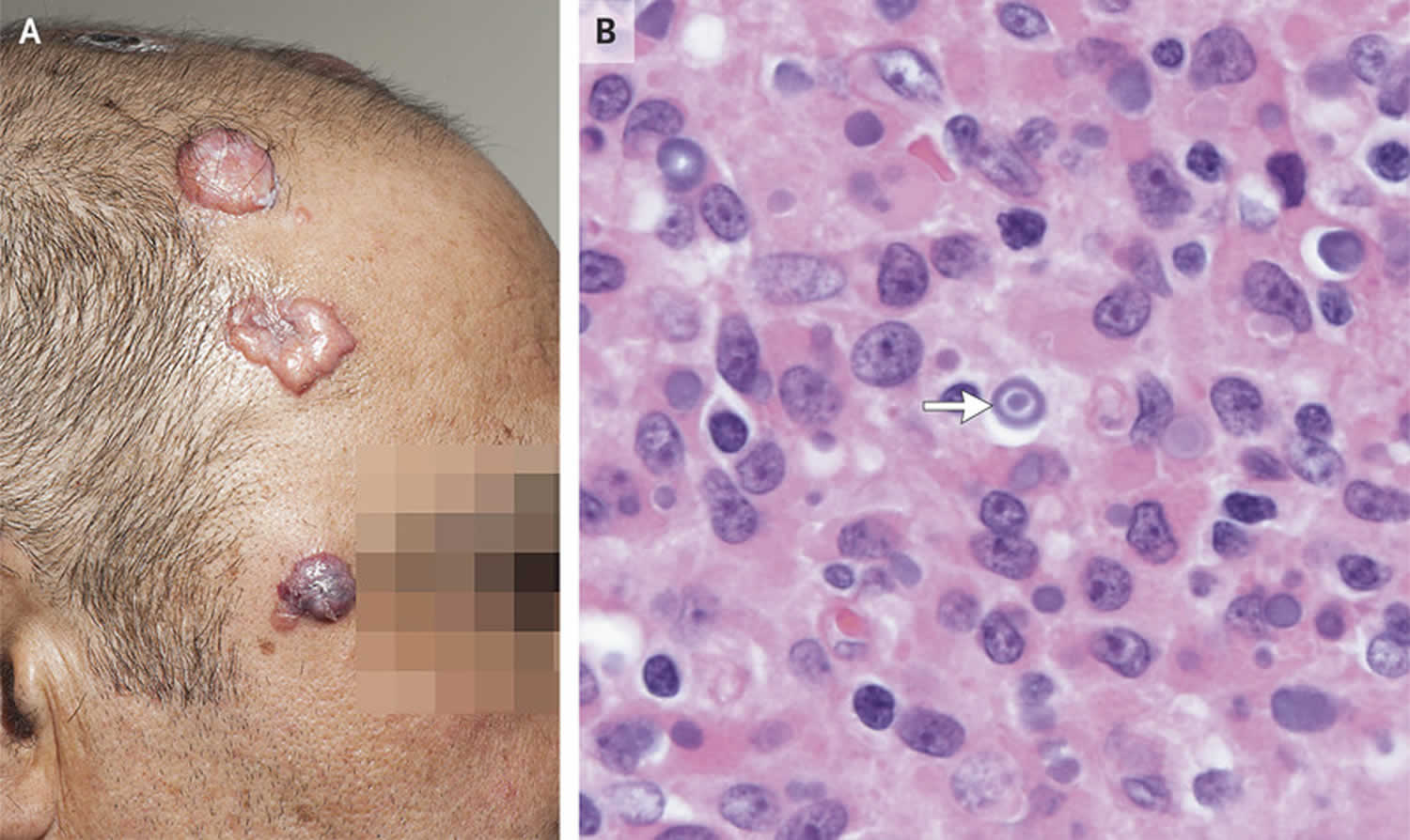

Figure 1. Malakoplakia skin

Footnote: A 53-year-old man who had undergone both liver and kidney transplantation within the previous 2 years presented to the infectious diseases clinic with a 4-month history of progressively enlarging, painless nodules on his scalp (Panel A) and perianal region. He otherwise felt well. The immunosuppressive medications that he was receiving included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisolone. Four weeks before the development of the skin lesions, he had received pulse methylprednisolone for acute cellular rejection of the transplanted kidney. Biopsy of the lesions identified von Hansemann cells containing Michaelis-Gutmann bodies (basophilic inclusions) (Panel B, arrow), and cultures grew Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A diagnosis of malakoplakia was made. Management combines prolonged antibiotic therapy, immunosuppression reduction, and sometimes surgical excision. The patient was treated with antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, along with a concurrent reduction in immunosuppression. After 6 months of treatment, the lesions regressed, with some residual scarring.

[Source 13 ]Malakoplakia skin signs and symptoms

Malakoplakia of the skin most commonly affects the perianal and genital area, presenting as asymptomatic, itchy or painful growths (tumors).

The skin lesions may be solitary or multiple, arranged in lines or across folds of skin. They are:

- Firm papules or nodules up to 2cm in diameter

- Skin-colored, yellow or pink

- Smooth, sometimes with a central dimple or draining sinus.

The lesions may ulcerate.

Malakoplakia of the tongue usually causes a feeling of something in the throat affecting swallowing or a lump. Pain may be associated. Symptoms may be present for days, weeks or months. On examination, the single lesion is a yellow, pink or tan colored soft tumor mass up to 4 cm in diameter, usually located on the base of the tongue.

Malakoplakia skin diagnosis

Cutaneous malakoplakia diagnosis is made on the characteristic histology of a biopsy or excision specimen of the tumor.

The diagnostic feature is the presence of von Hansemann cells containing Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. These intracellular bodies stain positively for calcium and iron and, when fully developed, they resemble an owl’s eye.

Bacterial culture will determine which organism is involved.

Malakoplakia skin treatment

Many tongue and skin lesions are biopsied or excised initially on suspicion of cancer or other unusual forms of inflammation. Wide surgical excision is not usually recommended.

Additional treatment is usually required as recurrence can occur after surgery. Options have included:

- Antibiotics – most commonly trimethoprim + sulphamethoxazole. The choice of antibiotic will depend on the causative organism. Clofazamine has been used successfully as it improves bacterial killing by white cells. Quinolones and rifampicin have good penetration of phagocytes (immune cells).

- Ascorbic acid (vitamin C)

- Reduction of immunosuppressive medications

Malakoplakia skin prognosis

Malakoplakia of the skin or tongue in isolation has an excellent prognosis. In some cases, there have been a spontaneous resolution. However, approximately 25% of cases with skin lesions have associated internal organ involvement, which can affect the outcome.

Malakoplakia causes

Malakoplakia is an unusual granulomatous inflammatory disease of uncertain cause, hypothesized to be due to defective intraphagolysosomal digestive activity of macrophages and monocytes leading to inadequate killing of ingested bacteria 14. The most commonly associated organisms are gram-negative bacilli including, most frequently, E. coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae 15. Nearly 90% of the patients have coliform urine infections and 40% have autoimmune disease or some type of immunodeficiency 16. Witherington et al. 17 have hypothesized that diminished monocytic bactericidal activity against E. coli is responsible for the unusual immunologic response that causes malakoplakia. It may be suggested that micro-organisms phagocytosed by the macrophages may either remain viable or partially digested in these cells, because of defective phagocytic digestion. These bacteria-laden histiocytes may remain at the site of implantation or enter into the lymphatic system, eventually localizing to regional lymph nodes. Therefore, the mechanism may be similar to lymph-node involvement in other infective processes such as tuberculosis and Whipple’s disease 15.

The abnormal function of macrophages in digesting bacteria is attributed to low levels of intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) and diminished release of β-glucuronidase 18. The reduction in the ratio of cGMP:cAMP which affects the “redox” status of the cell, thereby affecting the lysosomal phagocytosis and causing defective microtubular assembly, was postulated to be the main defect in malakoplakia pathogenesis 9.

Malakoplakia symptoms

Malakoplakia of bladder has symptoms of bladder irritability, hematuria, dysuria, etc 19. Upper urinary tract involvement as seen in 15% of the cases may manifest as upper urinary tract obstruction, fever, flank pain, or a mass 8.

Malakoplakia diagnosis

Malakoplakia is diagnosed by its pathognomonic features of von Hansemann histiocytes (which are large mononuclear phagocytes) containing Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Michaelis–Gutmann bodies are intracytoplasmic or extracellular oval basophilic structures of targetoid or bull’s eye or concentric owl eye appearance consisting of mineralized (calcium phosphate crystals) undigested bacterial components trapped in lysosomes of macrophages and monocytes 14. Michaelis-Gutmann bodies stain positive with periodic acid-schiff reagent, von Kossa’s reaction for calcium and Perl’s ferrocyanide reaction to ferric iron. However, they are not absolutely necessary for diagnosis as they are absent during the early stage of disease. The overlying urothelium is benign and may be hyperplastic, metaplastic, or ulcerated, but is usually intact 20.

Malakoplakia treatment

Treatment of malakoplakia is primarily medical with prolonged course of antibiotics such as quinolones as a mainstay and if failed, then surgery of the affected site 9. After the initial treatment with antibiotics, if there is a persistence of plaques in the bladder, they can be endoscopically resected and cystoscopically followed up. However, malakoplakia being mostly a diagnosis confirmed only on histopathology, in cases where it presents as a mass, mimicking malignancy, biopsy, or excision, as indicated, is advocated for both diagnostic and curative purposes. Use of cholinergic agents such as bethanechol as a treatment had been discussed and is controversial with conflicting literature on its benefits owing to its action of increasing cGMP 21. Similarly, ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) also may be used as a treatment owing to its property of reducing cAMP 22.

Malakoplakia prognosis

The prognosis of bilateral renal involvement is poor with 100% mortality within 6 months irrespective of the treatment chosen 23. Unilateral renal or upper tract involvement needs nephrectomy and has good results. It is not known if leaving behind the positive surgical margins following resection has any bearing on the prognosis. Focal involvement of only lower ureter can be treated with local excision and ureteroneocystostomy. Malakoplakia of the lower urinary tract is more benign with a good prognosis 22.

- Dobyan DC, Truong LD, Eknoyan G. Renal malacoplakia reappraised. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993 Aug;22(2):243-52. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70313-x[↩][↩]

- Wielenberg AJ, Demos TC, Rangachari B, Turk T. Malacoplakia presenting as a solitary renal mass. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:1703-5.[↩]

- Scott EV, Scott WF Jr. A fatal case of malakoplakia of the urinary tract. J Urol 1958;79:52-6.[↩]

- PozoMengual B, Burgos Revilla FJ, BrionesMardones G, Linares Quevedo A, García-Cosio Piqueras M. Bladder malacoplakia with lymphatic involvement and an aggressive course. Actas Urol Esp 2003;27:159-63.[↩]

- Nuciforo PG, Moneghini L, Braidotti P, Castoldi L, De Rai P, Bosari S. Malakoplakia of the pancreas with diffuse lymph-node involvement. Virchows Arch 2003;442:82-5.[↩][↩]

- Gidwani AL, Gidwani SA, Khan A, Carson JG. Concurrent malakoplakia of cervical lymph nodes and prostatic adenocarcinoma with bony metastasis: Case report. Ghana Med J 2006;40:151-3.[↩]

- McClure J. Malakoplakia of the gastrointestinal tract. Postgrad Med J 1981;57:95-103.[↩]

- Stanton MJ, Maxted W. Malacoplakia: A study of the literature and current concepts of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. J Urol 1981;125:139-46.[↩][↩][↩]

- Pakalapati S, Parachuri S, Kakarla VR, Byrappa MB. Isolated urachal malakoplakia mimicking malignancy. Urol Ann 2017;9:92-5. https://www.urologyannals.com/text.asp?2017/9/1/92/198900[↩][↩][↩]

- Hegde S, Coulthard MG. End stage renal disease due to bilateral renal malakoplakia. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2004;89:78-79. https://adc.bmj.com/content/archdischild/89/1/78.full.pdf[↩]

- Gupta K, Thakur S. Pulmonary malakoplakia: A report of two cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2011;54:133-5.[↩][↩]

- Schmerber S, Lantuejoul S, Lavieille JP, Reyt E. Malakoplakia of the neck. Arch Otolarngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:1240-2.[↩]

- Cutaneous Malakoplakia. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:580. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm1809037[↩]

- Lou TY, Teplitz C. Malakoplakia: Pathogenesis and ultrastructural morphogenesis. A problem of altered macrophage (phagolysosomal) response. Hum Pathol 1974;5:191-207.[↩][↩]

- Khera R, Narla S, Uppin SG, Uppin MS, Paul RT. Isolated malakoplakia of inguinal lymph node: A rare case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2013;56:443-5. https://www.ijpmonline.org/text.asp?2013/56/4/443/125365[↩][↩]

- Stanton MJ, Maxted W. Malakoplakia: A study of the literature and current concepts of pathogenesis. J Urol 1981;125:139-46.[↩]

- Witherington R, Branan WJ Jr, Wray BB, Best GK. Malacoplakia associated with vesicoureteral reflux and selective immunoglobulin A deficiency. J Urol. 1984 Nov;132(5):975-7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49975-7.[↩]

- Govender D, Ahmed SE. Malakoplakia and tuberculosis. Pathology 1999;31:280-3.[↩]

- Darvishian F, Teichberg S, Meyersfield S, Urmacher CD. Concurrent malakoplakia and papillary urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2001;31:147-50.[↩]

- Smith BH. Malacoplakia of the urinary tract: A study of twenty-four cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1965;43:409-17.[↩]

- Zornow DH, Landes RR, Morganstern SL, Fried FA. Malacoplakia of the bladder: Efficacy of bethanechol chloride therapy. J Urol 1979;122:703-4.[↩]

- Dasgupta P, Womack C, Turner AG, Blackford HN. Malacoplakia: Von Hansemann’s disease. BJU Int 1999;84:464-9.[↩][↩]

- Dhabalia JV, Nelivigi GG, Jain NK, Suryavanshi M, Kakkattil S. Malakoplakia of the ureter: An unusual case. Indian J Urol 2008;24:261-2. https://www.indianjurol.com/text.asp?2008/24/2/261/40627[↩]