Uterine Sarcoma

Uterine sarcoma is an extremely rare type of uterine cancer or cancer of the uterus (womb) that originates in the muscle or connective tissues of your uterus, rather than the inner lining (endometrium) 1, 2. Uterine sarcoma is a rare cancer, making up about 2% to 5% of all uterine cancers 3. Uterine sarcomas include leiomyosarcomas, endometrial stromal sarcomas, and adenosarcomas. The most common types of uterine sarcomas are leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. Most uterine sarcomas happen in people over the age of 40 and the average age at diagnosis is about 60 years old 3. Black women tend to have uterine leiomyosarcomas twice as often as White women, but not other types of uterine sarcomas. Uterine sarcoma symptoms may include unusual bleeding, pain and feeling full. Uterine sarcoma is often diagnosed later stages, making it more challenging to treat. Treatment usually involves surgery to remove your uterus, along with your ovaries and fallopian tubes commonly known as a total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Other treatment may include radiation therapy, chemotherapy or hormone therapy.

The National Cancer Institute’s estimates for uterine sarcoma in the United States for 2025 are 4:

- About 69,120 new cases of uterine sarcoma

- About 13,860 deaths from uterine sarcoma

- The rate of new cases of uterine cancer was 28.3 per 100,000 women per year. Approximately 3.1 percent of women will be diagnosed with uterine cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2018–2021 data.

- The death rate was 5.3 per 100,000 women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2018–2022 cases and 2019–2023 deaths.

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 81.1%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 2.2%.

- In 2022, there were an estimated 886,198 women living with uterine cancer in the United States.

The main symptoms of uterine sarcoma are similar to endometrial cancer and non-cancerous growths, such as uterine fibroids. It’s important to see your doctor if you notice any of these signs:

- Unusual bleeding from your vagina that’s unrelated to menstrual periods or that happens after menopause.

- Vaginal bleeding with a smelly discharge.

- A mass (lump or growth) in your vagina or pelvis.

- Feeling of fullness in your abdomen.

- Pelvic pain.

- Having to pee often.

- Constipation.

You may not notice symptoms until the uterine sarcoma has progressed to a more advanced stage. In rare instances, women with uterine sarcoma are asymptomatic (don’t notice symptoms).

Doctors don’t know exactly what causes most uterine sarcomas, but certain risk factors have been identified.

Certain factors may put you at greater risk of having uterine sarcoma.

- Pelvic radiation. Radiation treatment in your pelvic area may increase your risk of developing uterine sarcoma. Although pelvic radiation increases the risk of developing a uterine sarcoma, the benefit of pelvic radiation in treating other cancers often far outweighs the risk of developing a rare cancer such as uterine sarcoma many years later. Sarcomas rarely form after pelvic radiation, but when they do, they usually appear 5 to 25 years after radiation.

- Tamoxifen. Tamoxifen is a hormone therapy medication, specifically a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), primarily used to treat and prevent breast cancer in both men and women. Tamoxifen works by blocking the effects of estrogen on breast cancer cells, which can help stop their growth and spread. Tamoxifen is often prescribed for women who have not yet gone through menopause and have estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Long-term use of tamoxifen to treat breast cancer (five or more years) increases your risk of developing uterine sarcoma. The risk of developing uterine sarcomas while taking tamoxifen is small and there are not specific things you can do to prevent a uterine sarcoma if you’re taking it. But doctors will most likely watch you closely with regular pelvic exams and ask you to get medical care as soon as possible if you start to bleed abnormally from the uterus.

- Genetics. Possessing the gene that causes an eye cancer called retinoblastoma (RB1 gene) increases your risk of developing some types of uterine sarcoma 5, 6. Women who have had a type of eye cancer called congenital (heritable) retinoblastoma as a child have an increased risk of soft tissue sarcomas, including uterine sarcomas.

- Family history of kidney cancer. A rare family cancer syndrome called hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) has been linked to an increased risk of uterine sarcomas.

Black women are twice as likely as women who are white to develop uterine sarcomas. Researchers aren’t sure why race is a risk factor when it comes to uterine sarcoma.

If your doctor thinks you might have uterine sarcoma, she/he will perform a physical examination and ask you about your personal and family medical history. Your doctor will also conduct a pelvic examination of your vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and rectum. To examine these organs, your doctor inserts a gloved finger or two into your vagina and rectum to feel for anything unusual. Your doctor may also use a speculum to look inside your vagina.

If your doctor suspects cancer based on your symptoms and/or exam, you may be told you need other tests and also be referred to a gynecologist or a doctor specializing in cancers of the female reproductive system called a gynecologic oncologist. Your gynecological oncologist will help with both diagnosis and treatment for uterine sarcoma.

Your doctor may also perform the following procedures:

- Transvaginal ultrasound: Ultrasound creates images of soft tissue structures, including your reproductive organs. A specialized transducer is inserted in your vaginal canal about 2 to 3 inches to examine your uterus and ovaries. Sometimes uterine sarcoma and fibroids appear similar on an ultrasound.

- Endometrial biopsy: Your doctor removes a tissue sample from the lining of your uterus for examination. Your doctor can confirm a uterine sarcoma by examining its cells underneath a microscope after either a biopsy or a hysterectomy.

You may need additional tests to stage your cancer once you’ve been diagnosed with uterine sarcoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT scans, PET scans, and chest X-rays can reveal whether your cancer has spread throughout your body.

When possible, most women with uterine sarcoma have surgery to remove the cancer. Radiation, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy are sometimes used to help lower the risk of the cancer coming back after surgery. These treatments may also be used for cancers that cannot be removed with surgery or when a woman can’t have surgery because she has other health problems.

Surgery alone can be curative if the cancer is contained within the uterus. The value of pelvic radiation therapy is not established. Current studies consist primarily of phase 2 chemotherapy trials for patients with advanced disease. Adjuvant chemotherapy following complete resection for patients with stage 1 or 2 disease was not found to be effective in a randomized trial 7. Yet, nonrandomized trials have reported improved survival following adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy 8, 9, 10.

What is uterus

The uterus is a hollow, muscular organ shaped somewhat like an inverted pear. The uterus receives the embryo that develops from an oocyte fertilized in the uterine tube, and sustains its development.

In its nonpregnant, adult state, the uterus is about 7 centimeters long, 5 centimeters wide (at its broadest point), and 2.5 centimeters in diameter. The size of the uterus changes greatly during pregnancy and it is somewhat larger in women who have been pregnant. The uterus is located medially in the anterior part of the pelvic cavity, superior to the vagina, and usually bends forward over the urinary bladder (see Figure 3).

The upper two-thirds or body (corpus), of the uterus has a domeshaped top called the fundus (see Figure 1). The uterine tubes (also called Fallopian tubes) connect at the upper lateral edges of the uterus. The lower third of the uterus is called the cervix. This tubular part extends downward into the upper part of the vagina. The cervix surrounds the opening called the cervical orifice, through which the uterus opens to the vagina.

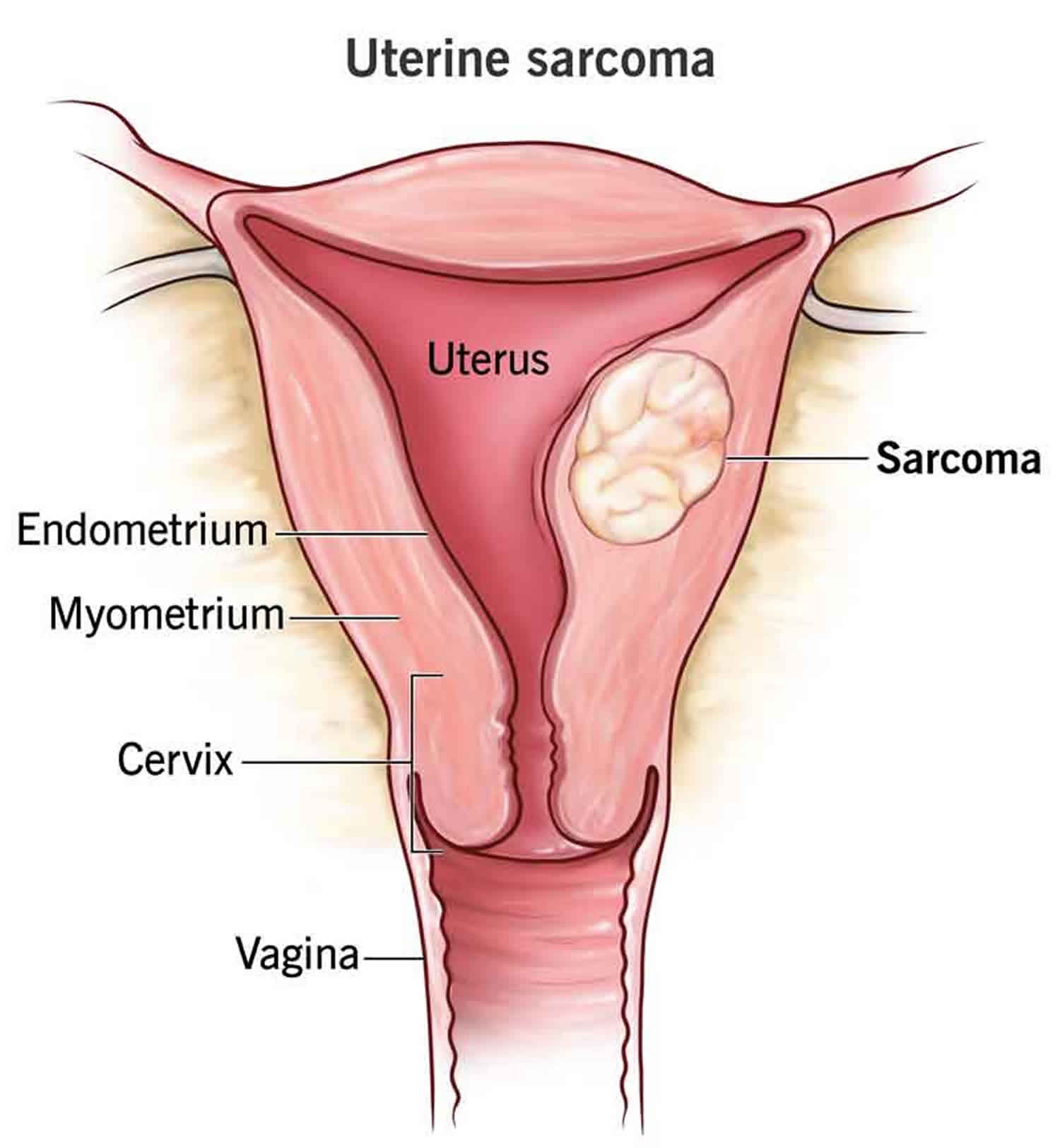

The uterine wall is thick and has three layers (Figure 1). The endometrium, the inner mucosal layer, is covered with columnar epithelium and contains abundant tubular glands. The myometrium, a thick, middle, muscular layer, consists largely of bundles of smooth muscle cells. During the monthly female menstrual cycles and during pregnancy, the endometrium and myometrium change extensively. The myometrium or muscle layer is needed to push a baby out during childbirth. The perimetrium consists of an outer serosal layer, a layer of tissue coating the outside of the uterus and part of the cervix.

Uterus anatomy

The uterus is supported by the muscular floor of the pelvis and folds of peritoneum that form supportive ligaments around the organ, as they do for the ovary and uterine tube. The broad ligament has two parts: the mesosalpinx mentioned earlier and the mesometrium on each side of the uterus. The cervix and superior part of the vagina are supported by cardinal (lateral cervical) ligaments extending to the pelvic wall. A pair of uterosacral ligaments attaches the posterior side of the uterus to the sacrum, and a pair of round ligaments arises from the anterior surface of the uterus, passes through the inguinal canals, and terminates in the labia majora.

As the peritoneum folds around the various pelvic organs, it creates several dead-end recesses and pouches (extensions of the peritoneal cavity). Two major ones are the vesicouterine pouch, which forms the space between the uterus and urinary bladder, and rectouterine pouch between the uterus and rectum (see Figure 3).

The uterine blood supply to the uterus is particularly important to the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. A uterine artery arises from each internal iliac artery and travels through the broad ligament to the uterus (Figure 2). It gives off several branches that penetrate into the myometrium and lead to arcuate arteries. Each arcuate artery travels in a circle around the uterus and anastomoses with the arcuate artery on the other side. Along its course, it gives rise to smaller arteries that penetrate the rest of the way through the myometrium, into the endometrium, and give off spiral arteries. The spiral arteries wind tortuously between the endometrial glands toward the surface of the mucosa. They rhythmically constrict and dilate, making the mucosa alternately blanch and flush with blood.

Figure 1. Uterus anatomy

Figure 2. Blood supply to the uterus

Figure 3. Uterus location

Figure 4. Uterus location in the female pelvis

What is the function of the uterus?

The lumen of the uterus is roughly triangular, with its two upper corners opening into the uterine tubes. In the nonpregnant uterus, the lumen isn’t a hollow cavity but rather a potential space; the mucous membranes of the opposite walls are pressed against each other with little room between them. The lumen communicates with the vagina by way of a narrow passage through the cervix called the cervical canal. The superior opening of this canal into the body of the uterus is the internal os and its opening into the vagina is the external os. The canal contains cervical glands that secrete mucus, thought to prevent the spread of microorganisms from the vagina into the uterus. Near the time of ovulation, the mucus becomes thinner than usual and allows easier passage for sperm.

The uterine wall consists of three layers. The outermost layer, the perimetrium, is a thin serosa of simple squamous epithelium and loose connective tissue. The middle and thickest layer is the myometrium, about 1.25 cm thick in the nonpregnant uterus. It is composed mainly of bundles of smooth muscle that sweep downward from the fundus and spiral around the body of the uterus. The myometrium is less muscular and more fibrous near the cervix; the cervix itself is almost entirely collagenous. The muscle cells of the myometrium are about 40 μm long immediately after menstruation, but they are twice this long at the middle of the menstrual cycle and 10 times as long in pregnancy. The function of the myometrium is to produce the labor contractions that help to expel the fetus.

The innermost layer is a mucosa called the endometrium. It has a simple columnar epithelium, compound (branching) tubular glands, and a lamina propria populated by leukocytes, macrophages, and other cells. The superficial half to two-thirds of it, called the functional layer (stratum functionalis), is shed in each menstrual period. The deeper layer, called the basal layer (stratum basalis), stays behind and regenerates a new functional layer in the next cycle. When pregnancy occurs, the endometrium is the site of attachment of the embryo and forms the maternal part of the placenta from which the fetus is nourished.

Figure 5. Endometrium of the uterus and its blood supply

Uterine Sarcoma Types

Most uterine sarcomas are divided into a category, based on the type of cell they start in 2:

The most common histological types of uterine sarcomas include:

- Carcinosarcoma (mixed mesodermal sarcoma [40%–50%]).

- Leiomyosarcoma (30%).

- Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) (15%).

The uterine neoplasm classification of the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists and the World Health Organization (WHO) uses the term carcinosarcoma for all primary uterine neoplasms containing malignant elements of both epithelial and stromal light microscopic appearances, regardless of whether malignant heterologous elements are present 11.

Uterine leiomyosarcoma

Uterine leiomyosarcoma tumors start in the muscle layer of the uterus (the myometrium). Uterine leiomyosarcoma are the most common type. These tumors can grow and spread quickly.

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS)

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) tumors start in the supporting connective tissue (stroma) of the lining of the uterus (the endometrium).

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) tumors are often given a grade which helps to understand how fast it’s likely to grow and spread 12:

- If the tumor is low grade or low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS), the cancer cells only look slightly different from normal cells and the tumor tends to grow slowly. Women with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma tumors (LG-ESS) tend to have a better outlook (prognosis) than women with other kinds of uterine sarcomas 13. Most low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS) tumors also have proteins called estrogen receptors (ER) and/or progesterone receptors (PR), like some breast cancers 14 Having these proteins often means certain hormone drugs can help treat these types of uterine sarcomas.

- A high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS) tumor means the cancer cells look very different from normal cells, and the tumor is growing quickly. High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS) is most often found when the tumor is already large and/or has spread. High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS) are often harder to treat and have poor prognosis, with a median overall survival (OS) and a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 19.9 months and only 32.6%, respectively, according to the National Cancer Database 15. It is generally detected at an advanced stage, and effective adjuvant therapy has not yet been established.

Undifferentiated sarcoma

These cancers start in the endometrium (inner layer or lining of the uterus) or the myometrium (the middle thick layer of muscle of the uterus). Undifferentiated sarcoma grow and spread quickly and tend to have a poor prognosis (outlook).

Adenosarcoma

This type of sarcoma has normal gland cells that are mixed with cancer cells of the stroma (supporting connective tissue). These are generally low-grade cancers and usually have a good prognosis (outlook).

Is uterine sarcoma aggressive?

Uterine sarcoma typically grows faster and spreads more quickly than more common endometrial cancers. Still, not all uterine sarcomas are equally aggressive. Your doctor will consider where the sarcoma is located and what type it is to determine how aggressive it is.

Your doctor can also stage your cancer to see if it has spread.

Is uterine sarcoma cancer curable?

Uterine sarcoma is curable if it’s low-grade (mildly abnormal cells) and it hasn’t spread beyond your uterus. In some cases, additional treatment, like chemotherapy and radiation, may be needed to destroy the cancer cells completely.

How long does a person live with uterine sarcoma?

There’s no way to know for sure how long a woman with uterine sarcoma will live. Your survival rate will depend on the type of sarcoma you have, how much it’s spread, your age, your health and how your body is responding to treatment, among other factors (see below).

According to the National Cancer Institute, the survival rate for uterine sarcomas, five years post-diagnosis, ranges from 11% to 67%, depending on the type of sarcoma and how much it’s spread 4.

Uterine Sarcoma causes

Doctors don’t know exactly what causes most uterine sarcomas, but certain risk factors have been identified. Scientists continue to learn about changes in the DNA of certain genes that help when normal uterine cells develop into sarcomas. For example:

- Changes in the RB1, TP53, and PTEN genes have been found in uterine leiomyosarcomas.

- RB1 gene provides instructions for making a protein called pRB 16. This protein acts as a tumor suppressor, which means that it regulates cell growth and keeps cells from dividing too fast or in an uncontrolled way, a crucial role in preventing cancer development. Under certain conditions, pRB stops other proteins from triggering DNA replication, the process by which DNA makes a copy of itself. Because DNA replication must occur before a cell can divide, tight regulation of this process controls cell division and helps prevent the growth of tumors. Additionally, pRB interacts with other proteins to influence cell survival, the self-destruction of cells (apoptosis), and the process by which cells mature to carry out special functions (differentiation).

- TP53 gene is a tumor suppressor gene, which means that it regulates cell division by keeping cells from growing and dividing (proliferating) too fast or in an uncontrolled way 17. The TP53 gene provides instructions for making a protein called tumor protein p53 (or p53). Because p53 is essential for regulating DNA repair and cell division, it has been nicknamed the “guardian of the genome”. The p53 protein, encoded by the TP53 gene, acts as a “guardian of the genome” by responding to DNA damage and cell stress. When DNA damage is detected, p53 can either initiate DNA repair or trigger cell death (apoptosis) to prevent the spread of damaged cells. The p53 protein is located in the nucleus of cells throughout the body, where it attaches (binds) directly to DNA. When the DNA in a cell becomes damaged by agents such as toxic chemicals, radiation, or ultraviolet (UV) rays from sunlight, this protein plays a critical role in determining whether the DNA will be repaired or the damaged cell will self-destruct (undergo apoptosis). If the DNA can be repaired, p53 activates other genes to fix the damage. If the DNA cannot be repaired, this protein prevents the cell from dividing and signals it to undergo apoptosis. By stopping cells with mutated or damaged DNA from dividing, p53 helps prevent the development of tumors.

- PTEN gene is a tumor suppressor gene that plays a critical role in regulating cell growth and preventing the formation of tumors 18. The PTEN gene provides instructions for making an enzyme that is found in almost all tissues in your body. The enzyme acts as a tumor suppressor, which means that it helps regulate cell division by keeping cells from growing and dividing (proliferating) too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. To function, the PTEN enzyme attaches (binds) to another PTEN enzyme (dimerizes) then binds to the cell membrane. The PTEN enzyme modifies other proteins and fats (lipids) by removing phosphate groups, each of which consists of a cluster of oxygen and phosphorus atoms. Enzymes with this function are called phosphatases. The PTEN enzyme is part of a chemical pathway that signals cells to stop dividing and triggers cells to self-destruct through a process called apoptosis. Evidence suggests that this enzyme also helps control cell movement (migration), the sticking (adhesion) of cells to surrounding tissues, and the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis). Additionally, it likely plays a role in maintaining the stability of a cell’s genetic information. All of these functions help prevent uncontrolled cell proliferation that can lead to the formation of tumors. Mutations in the PTEN gene can lead to increased cancer risk and are associated with syndromes like Cowden syndrome and PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome

- Low‐grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) is often linked with an abnormal gene called JAZF1‐SUZ12.

- JAZF1-SUZ12 gene is a fusion protein resulting from a chromosomal translocation that disrupts the Polycomb Repressor Complex 2 (PRC2) and impairs chromatin repression, particularly in endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) 19. This fusion protein, found in many endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) cases, disrupts the normal function of Polycomb Repressor Complex 2 (PRC2), leading to changes in gene expression and cell differentiation 19.

- High‐grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS) has been linked with the abnormal gene YWHAE‐NUTM.

- YWHAE‐NUTM gene is a fusion gene, specifically YWHAE-NUTM2 (YWHAE-NUTM2B), that’s found in high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS) and other soft tissue sarcomas 20, 21. It is associated with aggressive behavior and is a diagnostic and prognostic marker. The YWHAE‐NUTM fusion results from a chromosomal translocation and is an oncogenic driver, affecting cell proliferation and cyclin D1 expression

Most women are diagnosed with uterine sarcomas are over 40 years of age, but women as young as 20 have received a uterine sarcoma diagnosis. The average age of uterine sarcoma diagnosis is approximately 60 years old.

Risk factors for developing uterine sarcoma

Certain factors may put you at greater risk of having uterine sarcoma.

- Pelvic radiation. Radiation treatment in your pelvic area may increase your risk of developing uterine sarcoma. Although pelvic radiation increases the risk of developing a uterine sarcoma, the benefit of pelvic radiation in treating other cancers often far outweighs the risk of developing a rare cancer such as uterine sarcoma many years later. Sarcomas rarely form after pelvic radiation, but when they do, they usually appear 5 to 25 years after radiation.

- Tamoxifen. Tamoxifen is a hormone therapy medication, specifically a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), primarily used to treat and prevent breast cancer in both men and women. Tamoxifen works by blocking the effects of estrogen on breast cancer cells, which can help stop their growth and spread. Tamoxifen is often prescribed for women who have not yet gone through menopause and have estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Long-term use of tamoxifen to treat breast cancer (five or more years) increases your risk of developing uterine sarcoma. The risk of developing uterine sarcomas while taking tamoxifen is small and there are not specific things you can do to prevent a uterine sarcoma if you’re taking it. But doctors will most likely watch you closely with regular pelvic exams and ask you to get medical care as soon as possible if you start to bleed abnormally from the uterus.

- Genetics. Possessing the gene that causes an eye cancer called retinoblastoma (RB1 gene) increases your risk of developing some types of uterine sarcoma 5, 6. Women who have had a type of eye cancer called congenital (heritable) retinoblastoma as a child have an increased risk of soft tissue sarcomas, including uterine sarcomas.

- Family history of kidney cancer. A rare family cancer syndrome called hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) has been linked to an increased risk of uterine sarcomas.

Black women are twice as likely as women who are white to develop uterine sarcomas. Researchers aren’t sure why race is a risk factor when it comes to uterine sarcoma.

Uterine Sarcoma signs and symptoms

The main symptoms of uterine sarcoma are similar to endometrial cancer and non-cancerous growths, such as uterine fibroids. It’s important to see your doctor if you notice any of these signs:

- Unusual bleeding from your vagina that’s unrelated to menstrual periods or that happens after menopause.

- Vaginal bleeding with a smelly discharge.

- A mass (lump or growth) in your vagina or pelvis.

- Feeling of fullness in your abdomen.

- Pelvic pain.

- Having to pee often.

- Constipation.

You may not notice symptoms until the uterine sarcoma has progressed to a more advanced stage. In rare instances, women with uterine sarcoma are asymptomatic (don’t notice symptoms).

Abnormal vaginal bleeding or spotting

Most people diagnosed with uterine sarcomas have abnormal bleeding (bleeding between periods, more bleeding during periods, or bleeding after menopause). This symptom is more often caused by conditions other than cancer, but it’s important to have any abnormal bleeding checked right away.

If you’ve gone through menopause, any vaginal bleeding or spotting is abnormal, and should be reported to your doctor right away.

Vaginal discharge

Some women with uterine sarcomas have a vaginal discharge that does not have any blood. A vaginal discharge is most often a sign of infection or another non-cancer condition, but it also can be a sign of cancer. Any abnormal vaginal discharge should be checked by your doctor.

Pain and/or a mass

Some women with uterine sarcomas might have pain in the pelvis or the abdomen and/or a mass (lump) that can be felt. You or your doctor may be able to feel the mass in your uterus, or you might have a feeling of fullness in your belly and/or pelvis.

Urine or bowel problems

A mass in the pelvis might push on the bladder which can cause you to urinate (pee) more often than usual. It might also disturb the bowels and cause constipation.

Uterine Sarcoma diagnosis

If your doctor thinks you might have uterine sarcoma, she/he will perform a physical examination and ask you about your personal and family medical history. Your doctor will also conduct a pelvic examination of your vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and rectum. To examine these organs, your doctor inserts a gloved finger or two into your vagina and rectum to feel for anything unusual. Your doctor may also use a speculum to look inside your vagina.

If your doctor suspects cancer based on your symptoms and/or exam, you may be told you need other tests and also be referred to a gynecologist or a doctor specializing in cancers of the female reproductive system called a gynecologic oncologist. Your gynecological oncologist will help with both diagnosis and treatment for uterine sarcoma.

Your doctor may also perform the following procedures:

- Transvaginal ultrasound: Ultrasound creates images of soft tissue structures, including your reproductive organs. A specialized transducer is inserted in your vaginal canal about 2 to 3 inches to examine your uterus and ovaries. Sometimes uterine sarcoma and fibroids appear similar on an ultrasound.

- Endometrial biopsy: Your doctor removes a tissue sample from the lining of your uterus for examination. Your doctor can confirm a uterine sarcoma by examining its cells underneath a microscope after either a biopsy or a hysterectomy.

You may need additional tests to stage your cancer once you’ve been diagnosed with uterine sarcoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT scans, PET scans, and chest X-rays can reveal whether your cancer has spread throughout your body.

Endometrial biopsy and tissue sampling

To find the reason for your abnormal vaginal bleeding, a small piece of tissue will be taken from the lining of your uterus (endometrium) and looked at closely in the lab by a pathologist. The tissue can also be removed by dilation and curettage (D&C). See below for a description of how this is done.

These procedures let the doctor see if the abnormal vaginal bleeding is caused by an overgrowth of cells in the endometrium (endometrial hyperplasia) that’s not cancer, endometrial cancer, uterine sarcoma, or some other problem. The tests will find endometrial stromal sarcomas, but not as many leiomyosarcomas (rare malignant tumors that develop in the smooth muscle tissue).

These tests don’t find leiomyosarcomas (rare malignant tumors that develop in the smooth muscle tissue) as often because these cancers start in the muscle layer of the wall of the uterus, not the inner lining. To be found by an endometrial biopsy or dilation and curettage (D&C), leiomyosarcomas need to have spread from the middle (muscle) layer to the inner lining of the uterus. In most cases, the only way to diagnose a leiomyosarcoma is by removing it with surgery. Many uterine sarcomas are diagnosed during or after surgery for what’s thought to be benign uterine fibroid tumors.

Endometrial biopsy

In this procedure, a very thin, flexible tube is put into your uterus through the cervix. Then, using suction, a small sample or amount of the uterine lining (endometrium) is taken out through the tube. Suctioning takes about a minute or less and may be done more than once to get enough tissue. The discomfort is a lot like severe menstrual cramps and can be helped by taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) like ibuprofen an hour before the biopsy, if approved by your doctor. This procedure is usually done in your doctor’s office.

Hysteroscopy

This procedure allows doctors to look inside the uterus. A thin long camera called a hysteroscope that is either soft and flexible or rigid is put into your uterus through the cervix. To get a better view, your uterus is then expanded by filling it with salt water (saline) or gas. This lets your doctor see and take out anything that looks abnormal, such as a cancer or a polyp, or take a tissue sample (biopsy). If your doctor is just taking a look, this procedure can be done with you awake, using local anesthesia (numbing medicine). But if a lot of tissue, a polyp, or a mass has to be removed, general or regional anesthesia is used. General anesthesia means you are given drugs that put you into a deep sleep and keep you from feeling pain. Regional anesthesia is a nerve block that numbs one area of the body.

Dilation and curettage (D & C)

If an endometrial biopsy is not possible or the results of the endometrial biopsy are not clear meaning they can’t tell for sure if there is cancer, a procedure called dilation and curettage (D&C) is usually done. A D&C is a surgical procedure that is usually done in the outpatient surgery area of a clinic or hospital. It’s done while the woman is under general or regional anesthesia or conscious sedation (medicine is given into a vein to make her drowsy). In a D&C, the cervix is dilated (opened) and a special surgical tool is used to remove the endometrial tissue from inside the uterus so it can be checked in the lab. A hysteroscopy may be done as well. Some women have mild-to-moderate cramping and discomfort after this procedure.

Cystoscopy and proctoscopy

If a woman has signs or symptoms that suggest uterine sarcoma has spread to the bladder or rectum, imaging can help to confirm this. Rarely, a camera or lighted tube might be used to look inside of these organs. These exams are called cystoscopy (to look in the bladder) and proctoscopy (to look in the rectum), and might be done only if imaging is not helpful.

Lab tests of biopsy and other samples

Any tissue or biopsy samples are looked at closely in the lab to see if there is cancer. If cancer is found, the lab report will say if it’s a carcinoma or sarcoma, what type it is, and its grade.

Tumor grade

Cancer cells are given a grade when they are removed from the body and checked in the lab. You may hear your doctor talk about the grade of your cancer. The grade is based on how much the cancer cells look like normal cells. The grade also describes how abnormal the tissues look under a microscope. The grade is used to help predict your outcome (prognosis) and to help figure out what treatments might work best.

The grade gives your doctor some idea of how your cancer might behave. A low grade cancer is likely to grow more slowly and be less likely to spread than a high grade one. Doctors can’t be certain exactly how the cells will behave. But the grade is a useful indicator.

Doctors sometimes look at the cancer grade to help stage the cancer. The stage of a cancer describes how big the cancer is and whether it has spread or not.

- Grade 1 (Low grade) – the cancer cells look very like normal cells and are growing slowly.

- Grade 2 (Intermediate grade) – the cells don’t look like normal cells. The cells may be growing more quickly than normal.

- Grade 3 (High grade) – the cancer cells look very abnormal and are growing quickly and more likely to spread.

- For example, high-grade sarcomas tend to grow and spread faster than low-grade sarcomas.

Some systems have more than 3 grades.

GX means that doctors can’t assess the grade. It is also called undetermined grade.

Differentiation

Another way of describing cancer cells is by how differentiated they are. Differentiation refers to:

- How well developed the tumor cells are.

- How cancer cells are organized in the tumor tissue

When cells and tissue structures are very like normal tissues, the tumor is called well differentiated. These tumors tend to grow and spread slowly.

Poorly differentiated or an undifferentiated tumors are made up of cells that look very abnormal. They aren’t arranged in the usual way. So the normal structures and tissue patterns are missing. These tumors may be more likely to spread into surrounding tissues or to other parts of the body.

Hormone receptor status

The tissue sample or biopsy might also be tested to see if the cancer cells have estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors. These hormone receptors are found on many endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) and some leiomyosarcomas. Cancers with estrogen receptors (ER+) are more likely to grow with estrogen, while those with progesterone receptors (PR+) often don’t grow if exposed to progesterone. These cancers may stop growing or even shrink when treated with certain hormone drugs. Hormone drugs may also be used to prevent the cancer from coming back after initial treatment (recurrence) if the cancer is found to have estrogen or progesterone receptors. Checking for estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors helps predict which cancers might benefit from hormone treatment.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests for cancer use various techniques, including X-rays, ultrasound, CT scans, MRI, and PET scans, to visualize internal structures and detect or assess cancer. These tests can help diagnose cancer, determine its spread, and monitor treatment effectiveness.

Transvaginal ultrasound

Ultrasound tests use sound waves to take pictures of parts of the body. For a transvaginal ultrasound, a probe that gives off sound waves is put into the vagina. The sound waves are used to make images of the uterus and other pelvic organs. These images can often show if there’s a tumor or lump and if it invades the myometrium (muscle layer of the uterus).

For an sonohysterogram or saline infusion sonogram, salt water (saline) is put into the uterus through a small tube before or during the transvaginal ultrasound. This lets the doctor see changes in the uterine lining more clearly.

Computed tomography (CT)

The CT scan is an x-ray test that makes detailed cross-sectional images of your body. CT scans are rarely used to diagnose uterine sarcoma, but they might be helpful in seeing if the cancer has spread to other organs.

CT-guided needle biopsy: CT scans can also be used to guide a biopsy needle exactly into an abnormal area or tumor. For this procedure, the patient remains on the CT scanning table while the doctor moves a biopsy needle through the skin and toward the tumor. CT scans are repeated until the needle is inside the tumor. A needle biopsy sample is then removed and looked at closely in the lab. This isn’t done to biopsy tumors inside the uterus, but might be used to biopsy areas that look like metastasis (cancer spread).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI scans also make cross-section pictures of your insides but use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. An MRI scan can help tell if a uterine tumor looks like cancer, but a biopsy is still needed to tell for sure. It can also help find out if any cancer has been left behind after surgery or if the cancer has grown into nearby structures which can help in making a treatment plan.

MRI scans are also very helpful in looking for cancer that has spread to the brain and spinal cord.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

In a PET scan, a slightly radioactive form of sugar (known as FDG) is injected into the blood and collects mainly in cancer cells.

PET/CT scan: Often a PET scan is combined with a CT scan using a special machine that can do both at the same time. This lets the doctor compare areas of higher radioactivity on the PET scan with a more detailed picture on the CT scan.

PET/CT scans can be useful for women with uterine sarcomas, if your doctor thinks the cancer might have spread but doesn’t know where.

Chest x-ray

An x-ray of the chest might be done to see if a uterine sarcoma has spread to the lungs and as part of the testing before surgery. If something suspicious is seen, your doctor may order more tests.

Uterine Sarcoma Stages

After a woman is diagnosed with uterine sarcoma, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes the amount of cancer spread in the body and helps determine how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

Uterine sarcoma stages range from stage I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And sometimes, a stage might be divided further using letters. An earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

The systems used to stage uterine sarcoma use the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system, which are basically the same 22, 23.

FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM both stage (classify) uterine sarcoma based on 3 factors:

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): How large is the cancer? Has the cancer grown out of the uterus into the pelvis or organs such as the bladder or rectum?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or organs?

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests done without surgery.

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system, effective January 2018. It is only for staging leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS).

Uterine sarcoma staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. Uterine Sarcoma Stages

| Stage | Stage grouping | FIGO Stage | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | T1 N0 M0 | 1 | The cancer is growing in the uterus, but has not started growing outside the uterus. It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1A | T1a N0 M0 | 1A | The cancer is only in the uterus and is no larger than 5 cm across (about 2 inches) (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1B | T1b N0 M0 | 1B | The cancer is only in the uterus and is larger than 5 cm across (about 2 inches). (T1b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2 | T2 N0 M0 | 2 | The cancer is growing outside the uterus but is not growing outside of the pelvis (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3A | T3a N0 M0 | 3A | The cancer is growing into tissues of the abdomen in one place only (T3a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3B | T3b N0 M0 | 3B | The cancer is growing into tissues of the abdomen in 2 or more places (T3b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3C | T1-T3 N1 M0 | 3C | The cancer is growing in the body of the uterus and it might have spread into tissues of the abdomen, but is not growing into the bladder or rectum (T1 to T3). The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1), but not to distant sites (M0). |

| 4A | T4 Any N M0 | 4A | The cancer has spread to the rectum or urinary bladder (T4). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N) but has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4B | Any T Any N M1 | 4B | The cancer has spread to distant sites such as the lungs, bones, or liver (M1). The cancer in the uterus can be any size and may or may not have grown into tissues in the pelvis and/or abdomen (including the bladder or rectum) (any T) and it might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). |

Footnotes: * The following additional categories are not listed on the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Uterine Sarcoma treatment

If you’ve been diagnosed with uterine sarcoma, your cancer team will discuss your treatment options with you. A combination of treatments may be used to treat uterine sarcoma. The choice of treatment depends largely on the type and stage of your cancer. Other factors might include your age, your overall health, whether you plan to have children, and your personal preferences.

When possible, most women with uterine sarcoma have surgery to remove the cancer. Radiation, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy are sometimes used to help lower the risk of the cancer coming back after surgery. These treatments may also be used for cancers that cannot be removed with surgery or when a woman can’t have surgery because she has other health problems.

Surgery alone can be curative if the cancer is contained within the uterus. The value of pelvic radiation therapy is not established. Current studies consist primarily of phase 2 chemotherapy trials for patients with advanced disease. Adjuvant chemotherapy following complete resection for patients with stage 1 or 2 disease was not found to be effective in a randomized trial 7. Yet, nonrandomized trials have reported improved survival following adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy 8, 9, 10.

Surgery for Uterine Sarcoma

Surgery is the main treatment for early stage uterine sarcoma 25. The goal of surgery is to remove all of the cancer in one procedure, and if possible in one piece. This usually means removing the entire uterus with the cervix (total hysterectomy). In some cases, the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and part of the vagina may also need to be removed. Some lymph nodes or other tissue may be taken out as well to see if the cancer has spread outside the uterus. What’s done depends on the type and grade of the cancer and how far it has spread. Your overall health and age are also important factors.

In some cases, tests done before surgery let the doctor plan the operation ahead of time. These tests include imaging studies, like ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI, as well as a pelvic exam, endometrial biopsy, and/or D&C. In other cases, the surgeon has to decide what needs to be done based on what they find during surgery. For example, sometimes there’s no way to know for sure that a tumor is cancer until it’s removed during surgery.

Total hysterectomy

Total hysterectomy surgery removes the whole uterus (the body of the uterus and the cervix). The loose connective tissue around the uterus called the parametrium, the tissue connecting the uterus and sacrum (the uterosacral ligaments), and the vagina are not removed 25. After a hysterectomy, a woman cannot become pregnant and give birth to children. Removing the ovaries and fallopian tubes is not part of a hysterectomy — officially it’s a separate procedure known as a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) 25. The bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is often done along with a hysterectomy in the same operation (see below).

If your uterus is removed through an incision (cut) in the front of your abdomen (belly), the surgery is called an abdominal hysterectomy. When the uterus is removed through the vagina, it’s called a vaginal hysterectomy. When it is removed through small incisions on the belly using a laparoscope it is called a laparoscopic hysterectomy. A laparoscope is a thin lighted tube with a video camera at the end. It can be put into your body through a small incision in your abdomen and lets your doctor see inside your body without making a big incision. Your doctor can use long, thin tools that are put in through other small incisions to operate. A laparoscope is sometimes used to help remove the uterus when the doctor is doing a vaginal hysterectomy. This is called a laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Your uterus can also be removed through the abdomen with a laparoscope, sometimes with a robotic approach, in which the surgeon sits at a control panel in the operating room and moves robot arms to operate. Laparoscopic procedures have shorter recovery times than abdominal hysterectomies, but are not possible to all patients. Talk with your surgeon about how the surgery will be done and why it’s the best plan for you.

If lymph nodes or other organs need to be seen, removed, or tested, this can be done through the same incision as the abdominal hysterectomy or laparoscopic hysterectomy. If a hysterectomy is done through the vagina, lymph nodes can be removed after the hysterectomy by using a laparoscope.

Either general or regional anesthesia is used for the procedure. This means that the patient is in a deep sleep or is sedated and numb from the waist down.

For an abdominal hysterectomy the hospital stay is usually 3 to 5 days. Complete recovery takes about 4 to 6 weeks. A woman who gets a laparoscopic procedure or vaginal hysterectomy can usually go home the same day as the surgery and recovery often takes 2 to 3 weeks.

Surgical complications are rare but could include bleeding, wound infection, and damage to the urinary (bladder and/or ureters) or bowel systems.

Radical hysterectomy

Radical hysterectomy removes the entire uterus as well as the tissues next to the uterus and cervix (parametrium and uterosacral ligaments) and the upper part of the vagina (near the cervix). Radical hysterectomy is not often used for uterine sarcomas, but may be needed if the tumor appears to have spread to the nearby tissues.

Radical hysterectomy is most often done through an abdominal surgical incision or with a laparoscope, with or without a robotic approach in which the surgeon sits at a control panel in the operating room and moves robot arms to operate, but it can also be done through the vagina. Most people having a radical hysterectomy also have some lymph nodes removed, either through the abdominal incision or with a laparoscope. A radical hysterectomy is done using general anesthesia.

Because more tissue is removed by a radical hysterectomy than with a total hysterectomy, your hospital stay might be longer.

After a radical hysterectomy, a woman cannot become pregnant and give birth to children.

Complications associated with a radical hysterectomy can include bleeding, wound infection, and damage to the urinary (bladder and/or ureters) or bowel systems. If some of the nerves of the bladder are damaged, a catheter is often needed to empty the bladder for some time after surgery. This usually gets better with time and the catheter can be taken out later.

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO)

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) removes both fallopian tubes and both ovaries. In treating uterine sarcomas, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is usually done at the same time the uterus is removed (hysterectomy). If both of your ovaries are removed, you will go into menopause if you have not done so already.

Lymph node surgery

Sometimes during surgery it looks like the cancer might have spread outside the uterus or nearby lymph nodes look swollen on imaging tests. In this case, your surgeon might do a lymph node dissection (lymphadenectomy) or a lymph node sampling, which removes lymph nodes in the pelvis and/or those around the aorta (the main artery that runs from the heart down along the back of the abdomen and pelvis). These lymph nodes are then checked in the lab to see if they have cancer cells. If cancer is found in the lymph nodes, it means that the cancer has already spread outside the uterus. Cancer in the lymph nodes is often associated with a poorer prognosis (outlook).

Lymph node surgery (lymphadenectomy) is done through the same surgical incision in your abdomen as the abdominal hysterectomy or laparoscopic hysterectomy. If a vaginal hysterectomy has been done, the lymph nodes can be removed with laparoscopic surgery.

While some women might have their lymph nodes removed during surgery for uterine sarcoma, it is still not known if this improves their outlook unless the lymph nodes have cancer cells in them. Studies are being done to help answer this question.

A side effect of removing lymph nodes in the pelvis can lead to a build-up of fluid in the legs, called lymphedema. This is more likely if radiation is given after surgery.

Other procedures that may be done during surgery

- Omentectomy: The omentum is a layer of fatty tissue that covers the abdominal contents like an apron. Cancer sometimes spreads to this tissue. When the omentum is removed, its called an omentectomy. The omentum is sometimes removed at the same time the hysterectomy is done if cancer has spread there, or as a part of staging.

- Peritoneal biopsies: The tissue lining the pelvis and abdomen is called the peritoneum. Peritoneal biopsies remove small pieces of this lining to check for cancer cells.

- Pelvic washings: In this procedure, the surgeon “washes” the abdominal and pelvic cavities with salt water (saline), collects it, and then sends the fluid to the lab to see if it s has cancer cells.

- Tumor debulking: If cancer has spread throughout the abdomen, the surgeon may attempt to remove as much of the tumor as possible. This is called debulking. For some types of cancer, debulking can help other treatments (like radiation or chemotherapy) work better.

Sexual impact of surgery

If you are premenopausal, removing your uterus stops menstrual bleeding (periods). If your ovaries are also removed, you will go into menopause. This can lead to vaginal dryness and pain during sex. These symptoms can be improved with non-hormonal treatments or in some cases, estrogen treatment. Estrogen treatment isn’t safe for all women with uterine sarcoma.

While physical and emotional changes can affect the desire for sex, these surgical procedures do not prevent a woman from feeling sexual pleasure. A woman does not need ovaries or a uterus to have sex or reach orgasm. Surgery can actually improve a woman’s sex life if the cancer had caused problems with pain or bleeding during sex.

Radiation Therapy for Uterine Sarcoma

Radiation therapy uses high-energy X-rays or particles to destroy cancer cells or slow their growth.

Radiation might be used to treat uterine sarcoma in these ways:

- After surgery (adjuvant radiation) it may help lower the chance of the cancer coming back in the pelvis. After surgery (adjuvant radiation) might be done for cancers that are high grade or when cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes. The entire pelvis or part of the pelvis may be treated with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Sometimes the radiation field will also include an area of the abdomen (belly) called the para-aortic field. This is the area around the aorta (the main artery). Brachytherapy (internal radiation) may also be used in some cases after surgery.

- Radiation therapy might be used alone or with chemo as the main treatment if surgery can’t be done because of other health problems.

- Radiation therapy might be used to treat problems caused by tumor growth, but is not intended to cure the cancer. For instance, radiation can be used to shrink a tumor that’s causing pain and swelling by pressing on nearby nerves and blood vessels. This is called supportive or palliative care.

Radiation therapy seems to help keep some uterine sarcomas from coming back after surgery, but there is not enough information to know if it can help someone live longer.

Types of radiation therapy that might be used for uterine sarcoma:

- External beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

- Internal radiation therapy or brachytherapy

Sometimes brachytherapy and external beam radiation therapy are used together. How much of the pelvis needs to be exposed to radiation therapy and the type(s) of radiation used depend on the extent of the disease.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Short-term side effects of radiation therapy include:

- Feeling tired (fatigue)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loose stools or diarrhea

- Bladder irritation

- Skin changes

- Low blood counts

Skin changes in the treated area can look and feeling sunburned. As the radiation passes through the skin to its target, it might damage the skin cells. This can cause irritation that ranges from mild redness to permanent discoloration or skin darkening. The skin might release fluid, which can lead to infection, so care must be taken to clean and protect the area exposed to radiation.

This same kind of damage that can happen to the skin can happen inside the vagina with brachytherapy. As long as there is not a lot of bleeding, a person can continue to have sex during radiation therapy. But the outer genitals and vagina may become sore and tender to touch, and many choose to stop having sex for a while to let the area heal.

Radiation can also irritate the bladder and may cause problems urinating (peeing). Bladder irritation, called radiation cystitis, can cause discomfort and an urge to urinate frequently.

Almost all side effects can be treated with medicines and many go away over time after treatment ends. If you’re having any side effects from radiation, discuss them with your cancer care team. There are things you can do to get relief from these symptoms or prevent them.

Long-term side effects of radiation

Radiation can also cause some side effects that can last a long time.

Radiation therapy might also cause scar tissue to form in the vagina. If the scar tissue makes the vagina shorter or more narrow it’s called vaginal stenosis. This can make vaginal sex painful. Stretching the walls of the vagina several times a week can help prevent this problem. This can be done by having sex 3 to 4 times a week or by using a vaginal dilator (a plastic or rubber tube used much like a tampon to stretch out the vagina). Still, vaginal dryness and pain with sex can be long-term problems after radiation.

Pelvic radiation can damage the ovaries, resulting in premature (early) menopause. But most women being treated for uterine sarcoma have already gone through menopause, either naturally or as a result of surgery to treat the cancer.

Radiation to the pelvis can block fluid drainage from the legs, leading to leg swelling. This is called lymphedema. It’s more common in those who had lymph nodes removed during surgery.

Pelvic radiation can also weaken bones, leading to fractures of the hips or pelvic bones. If you have had pelvic radiation, contact your doctor right away if you have pelvic pain. Such pain might be caused by a fracture, recurrent cancer, or other serious conditions, such as hemorrhagic cystitis (injury to the bladder with blood in the urine) or radiation proctitis (injury to the rectum with blood in the stool).

External beam radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is the more common type of treatment for uterine sarcoma. It focuses radiation from outside the body onto the cancer. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is much like getting an x-ray, but the radiation is stronger. A machine focuses the radiation on the area with the cancer. The procedure itself is painless, but may cause side effects. Each treatment lasts only a few minutes, but the setup time—getting you into place for treatment—usually takes longer.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is usually given 5 days a week for 4 or 5 weeks. The actual radiation treatment takes less than 30 minutes. Sometimes, a special mold of the pelvis and lower back is custom-made to be sure the person is in the exact same position for each treatment.

Brachytherapy (internal radiation)

Brachytherapy also known as internal radiation is another way to deliver radiation. Instead of aiming radiation beams from outside the body, a device containing radioactive materials is placed inside the body close to the tumor. People treated with this type of radiation are not radioactive after the implant is removed.

After hysterectomy, the tissues in the upper part of the vagina might need to be treated. In this situation, the radioactive material is put into the vagina. This is called vaginal brachytherapy.

When vaginal brachytherapy is needed, treatment is done in the radiation suite of the hospital or treatment center. About 6 to 8 weeks after the hysterectomy, the surgeon or radiation oncologist puts a special cylinder (applicator) into the vagina. The length of the cylinder (and the amount of the vagina treated) can vary, but the upper part of the vagina is always treated. Pellets of radioactive material are then put into the applicator. With this treatment, nearby structures, like the bladder and rectum, will get less radiation exposure.

There are 2 types of brachytherapy:

- Low-dose rate (LDR): In low-dose rate (LDR) brachytherapy, the radiation pellets are usually left in for 1 to 4 days at a time. The patient needs to stay very still to keep the applicator from moving during treatment, so they’re usually kept in the hospital on strict bed rest. More than one treatment may be needed.

- High-dose rate (HDR). In high-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy, the radiation is more intense. It’s given the same way as low-dose rate (LDR), but a higher dose of radiation is given over hours instead of days. Because the applicator is in for a shorter period of time, you can usually go home the same day. For uterine cancers, high-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy is often given daily or weekly for a total of about 3 doses.

Hormone Therapy for Uterine Sarcoma

Hormone therapy is the use of hormones or hormone-blocking drugs to treat cancer. Part of diagnosing uterine sarcoma includes tests that check the cancer cells to see if they have receptors (proteins) where hormones can attach. If they do have estrogen receptors (ER) and/or progesterone receptors (PR), hormone treatment might be a good option. Hormone therapy is mainly used to treat low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas (LG-ESS) and is rarely used for the other types of uterine sarcomas.

Aromatase inhibitors

After your ovaries are removed, or aren’t working (after menopause), some estrogen is still made in fat tissue. This becomes your body’s main source of estrogen. Drugs called aromatase inhibitors can stop this estrogen from being made. Aromatase inhibitors are a type of medication that reduces estrogen levels in your body, primarily used in postmenopausal women. They work by blocking the action of the aromatase enzyme, which is responsible for converting androgens into estrogen in peripheral tissues after menopause. Examples of aromatase inhibitors include letrozole (Femara), anastrozole (Arimidex), and exemestane (Aromasin). These drugs are most often used to treat breast cancer, but they are also helpful in treating low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, adenosarcoma, or other sarcomas that have estrogen and/or progesterone receptors.

These drugs are only useful for those whose ovaries have been removed or no longer work (like after menopause).

Side effects can include any of the symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness, as well as joint/muscle pain. If they are taken for a long time (years), these drugs can weaken bones, sometimes leading to osteopenia or osteoporosis.

Progestins

Progestins are man-made versions of the natural hormone progesterone, designed to mimic its effects in the body. The progestins used most often to treat estrogen-positive (ER+) and/or progesterone-positive (PR+) uterine sarcomas are megestrol (Megace) and medroxyprogesterone (Provera). Both of these drugs are pills you take every day.

Side effects can include increased blood sugar levels in patients with diabetes. Hot flashes, night sweats, and weight gain (from fluid retention and an increased appetite) also occur. Rarely, serious blood clots can happen in people taking progestins.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists also known as GnRHa or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists are synthetic substances that mimic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH), a naturally occurring hormone in your brain that stimulates the release of other hormones, including follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). These hormones, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), in turn, control the production of sex hormones in your ovaries. GnRH agonists work by initially stimulating the pituitary gland to release FSH and LH, but with continuous use, the pituitary gland becomes desensitized and stops producing these hormones, leading to a suppression of sex hormone production

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH) agonists are drugs used to lower estrogen levels in women who are premenopausal (are still having periods or have not gone through menopause). Before menopause, almost all of a woman’s estrogen is made by the ovaries. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH) agonists keep your ovaries from making estrogen. Examples of GNRH agonists include goserelin (Zoladex) and leuprolide (Lupron). These drugs are given as a shot into a muscle every 1 to 3 months.

Side effects can include any of the symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness. If they are taken for a long time, these drugs can weaken bones, sometimes leading to osteoporosis.

Chemotherapy for Uterine Sarcoma

Chemotherapy (chemo) is the use of anti-cancer drugs to treat cancer. The drugs can be taken by mouth as pills or injected by needle into a vein or muscle. These drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach almost all areas of the body, making this treatment useful for killing cancer cells in most parts of the body. This makes chemo a useful treatment for cancer that has spread outside of the uterus.

Not all women with uterine sarcoma will need chemo, but there are a few situations in which chemo might be recommended:

- After surgery (adjuvant therapy also called add-on therapy) chemo might be used to help keep the cancer from coming back later.

- Chemo might be used as the main therapy to treat the cancer if you are unable to have surgery.

- Sometimes chemo might be used to control uterine sarcoma that has spread to other parts of the body or come back after surgery. In this case, the goal may be to ease symptoms and try to keep the tumor from growing.

Chemo may not work for certain types of uterine sarcoma. And some types of uterine sarcoma have been found to respond better to certain drugs and drug combinations. The role of chemo, as well as the best chemo drugs to use are not clear. Still, a lot of clinical trials are looking at this.

Some of the drugs commonly used to treat uterine sarcomas include:

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- Docetaxel (Taxotere)

- Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

- Ifosfamide (Ifex)

- Dacarbazine (DTIC)

- Vinorelbine (Navelbine)

- Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil)

- Epirubicin (Ellence)

- Temozolomide (Temodar)

- Trabectedin (Yondelis)

Sometimes, more than one drug is used. For example, gemcitabine and docetaxel are often used together to treat leiomyosarcoma.

Side effects of chemotherapy for uterine sarcoma

These drugs kill cancer cells but can also damage some normal cells. This is what causes many side effects. Side effects of chemo depend on the specific drugs, the amount taken, and the length of time you are treated.

Many side effects are short-term and go away after treatment is finished, but some can last a long time or even be permanent. It’s important to tell your health care team if you have any side effects, as there are often ways to lessen them.

Some common chemo side effects include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Feeling tired (fatigue)

Chemo can damage the blood-producing cells of the bone marrow, leading to low blood cell counts. This can cause:

- An increased chance of infection from a shortage of white blood cells (neutropenia)

- Problems with bleeding or bruising from a shortage of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia)

- Feeling tired or short of breath due to low red blood cell counts (anemia)

Some side effects from chemotherapy can last a long time. For example, the drug doxorubicin can damage the heart muscle over time. The chance of heart damage goes up as the total dose of the drug goes up, so doctors limit how much doxorubicin can be given.

Targeted Drug Therapy for Uterine Sarcoma

Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that aims to attack specific proteins on cancer cells to stop their growth and spread. Unlike traditional chemotherapy, targeted therapies are designed to act on particular molecular targets in cancer cells, minimizing damage to healthy cells. These therapies can be used on their own or in combination with other treatments like chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation.

Research has shown that some uterine sarcomas make certain proteins or have gene changes that can be targeted with specific drugs to destroy cancer cells or slow their growth. Many of these drugs can be taken as pills and their side effects are different from those of chemotherapy sometimes less severe.

Some targeted drugs, for example, monoclonal antibodies, work in more than one way to control cancer cells and may also be considered immunotherapy because they boost the immune system.

Kinase inhibitors

Kinases are proteins in the cell or on its surface that normally send signals to the rest of the cell, such as telling the cell to grow. Drugs that block certain kinases (kinase inhibitors) can help stop or slow the growth of some tumors.

Pazopanib (Votrient) is a targeted drug that might be used to treat a leiomyosarcoma that has spread or come back after treatment.

Side effects include high blood pressure, diarrhea, nausea, headache, vomiting, and skin changes. More serious side effects can include bleeding in the lung or getting a hole in the bowel.

Targeted therapy is used to treat many types of cancer, but it’s still new for treating uterine sarcoma.

TRK inhibitors

Some uterine sarcomas have changes in one of the NTRK genes. This gene change causes them to make abnormal TRK proteins, which can lead to abnormal cell growth and cancer.

Larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) and entrectinib (Rozlytrek) are drugs that target the TRK proteins. These drugs can be used to treat advanced or recurrent (cancer that has come back) uterine sarcomas with NTRK gene changes.

These drugs are taken as pills, once or twice a day.

Common side effects of TRK inhibitors include muscle and joint pain, cough, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, constipation, fever, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.

PARP inhibitors

Olaparib (Lynparza), rucaparib (Rubraca), and niraparib (Zejula) are PARP inhibitors. By blocking the PARP pathway, these drugs make it very hard for tumor cells with an abnormal BRCA gene to repair damaged DNA, which often leads to the death of these cells. If you are not known to have a BRCA gene mutation, your doctor might test your blood or saliva to be sure you have one before starting treatment with one of these drugs.

Less than 10% of women with uterine leiomyosarcomas will have a BRCA2 gene mutation. Those that do might benefit from one of these PARP inhibitors.

Olaparib (Lynparza), rucaparib (Rubraca), and niraparib (Zejula) might be used to treat advanced uterine leiomyosarcomas, typically after chemotherapy has been tried.

All of these drugs are taken daily by mouth, as pills or capsules.

Immunotherapy for Uterine Sarcoma

Immunotherapy uses medicines to boost a person’s own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells more effectively. Immunotherapy typically works on specific proteins involved in the immune system to enhance the immune response. Side effects of these drugs are different from those of chemotherapy.

Some immunotherapy drugs, for example, monoclonal antibodies, work in more than one way to control cancer cells and may also be considered targeted drug therapy because they block a specific protein on the cancer cell to keep it from growing.

Immunotherapy is used to treat some types of uterine sarcomas.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors for uterine sarcomas

An important part of your immune system is its ability to keep itself from attacking normal cells in the body. To do this, it uses proteins or “checkpoints” on immune cells that need to be turned on or off to start an immune response. Drugs that block these checkpoint proteins called immune checkpoint inhibitors might be used to treat some uterine sarcomas.

PD-1 inhibitor

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a drug that targets PD-1 (a protein on immune system T cells that normally helps keep them from attacking other cells in the body). By blocking PD-1, these drugs boost the immune response against cancer cells. This can often shrink tumors or slow their growth.

Pembrolizumab might be an option to treat some advanced uterine sarcomas, typically after other treatments have been tried or when no other good treatment options are available, and if the cancer cells have a high tumor mutational burden (TMB-H), meaning the cancer cells have many gene mutations. The tumor cells can be tested for these gene changes.

This drug is an intravenous (IV) infusion and is typically given every 3 or 6 weeks.

Possible side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors

Side effects of these drugs can include fatigue, cough, nausea, skin rash, poor appetite, constipation, and diarrhea.

Other, more serious side effects occur less often.

- Infusion reactions: Some people might have an infusion reaction while getting these drugs. This is like an allergic reaction, and can include fever, chills, flushing of the face, rash, itchy skin, feeling dizzy, wheezing, and trouble breathing. It’s important to tell your doctor or nurse right away if you have any of these symptoms while getting these drugs.

- Autoimmune reactions: These drugs remove one of the protections on the body’s immune system. Sometimes the immune system starts attacking other parts of the body, which can cause serious or even life-threatening problems in the lungs, intestines, liver, hormone-making glands, kidneys, or other organs.

It’s very important to report any new side effects to your doctor quickly. If serious side effects do occur, treatment may need to be stopped and you may get high doses of corticosteroids to suppress your immune system.

Uterine Sarcoma Treatment by Type and Stage

The main treatment for early-stage uterine sarcoma is surgery to remove your uterus (hysterectomy), sometimes along with the fallopian tubes and ovaries (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). In certain cases the lymph nodes might be removed and checked . Surgery might be followed by treatment with radiation, chemotherapy (chemo), or hormone therapy. Targeted drug therapy and immunotherapy might also be used in advanced cancers.

Women who can’t have surgery because they have other health problems or because their cancer has spread are treated with radiation, chemo, or hormone therapy. Often some combination of these treatments is used.

Uterine Sarcoma Stage 1

In stage 1 uterine sarcoma, the tumor is found in the uterus only. Stage 1 uterine sarcoma is divided into stages 1A and 1B:

- In stage 1A, the tumor is 5 centimeters or smaller.

- In stage 1B, the tumor is larger than 5 centimeters.

Treatment of stage 1 leiomyosarcoma of the uterus, stage 1 endometrial stromal sarcoma, and stage 1 adenosarcoma of the uterus may include:

- Surgery (total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and periaortic selective lymphadenectomy).

- Surgery followed by radiation therapy to the pelvis.

- Surgery followed by chemotherapy.

A nonrandomized Gynecologic Oncology Group study examined the effect of pelvic radiation therapy on patients with stage 1 and 2 carcinosarcomas. Patients who had pelvic radiation therapy had a significant reduction in tumor recurrences within the radiation treatment field but no alteration in survival 26. A large nonrandomized study demonstrated improved survival and a lower local failure rate in patients with mixed mullerian tumors following postoperative external and intracavitary radiation therapy 27. One nonrandomized study that predominantly included patients with carcinosarcomas showed that adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and doxorubicin benefitted participants 10.

Uterine Sarcoma Stage 2

In stage 2 uterine sarcoma, the tumor has spread beyond the uterus but has not spread beyond the pelvis. Stage 2 uterine sarcoma is divided into stages 2A and 2B:

- In stage 2A, the tumor has spread to the ovary, fallopian tube, or connective tissues around the uterus.

- In stage 2B, the tumor has spread to other tissues in the pelvis.

Treatment of stage 2 leiomyosarcoma of the uterus, stage 2 endometrial stromal sarcoma, and stage 2 adenosarcoma of the uterus may include:

- Surgery (total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and periaortic selective lymphadenectomy).

- Surgery followed by radiation therapy to the pelvis.

- Surgery followed by chemotherapy.

A nonrandomized Gynecologic Oncology Group study examined the effect of pelvic radiation therapy on patients with stage 1 and 2 carcinosarcomas. Patients who had pelvic radiation therapy had a significant reduction in tumor recurrences within the radiation treatment field but no alteration in survival 26. One nonrandomized study that predominantly included patients with carcinosarcomas showed that adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and doxorubicin benefitted participants 10.

Uterine Sarcoma Stage 3

In stage 3 uterine sarcoma, the tumor has spread into tissues in the abdomen. Stage 3 uterine sarcoma is divided into stages 3A, 3B, and 3C:

- In stage 3A, the tumor has spread to one site in the abdomen.

- In stage 3B, the tumor has spread to more than one site in the abdomen.

- In stage 3C, the tumor has spread to lymph nodes in the pelvis and/or around the abdominal aorta (the largest blood vessel in the abdomen).

Treatment of stage 3 leiomyosarcoma of the uterus, stage 3 endometrial stromal sarcoma, and stage 3 adenosarcoma of the uterus may include:

- Surgery (total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, lymphadenectomy, and removal of all other tissue where tumor is found).

- A clinical trial of surgery followed by radiation therapy to the pelvis.

- A clinical trial of surgery followed by chemotherapy.