Adrenal hemorrhage

Adrenal hemorrhage also called adrenal apoplexy, is a relatively rare condition with a variable and nonspecific presentation that may lead to acute adrenal crisis, shock and death unless it is recognized promptly and treated appropriately 1. Several risk factors have been associated with adrenal hemorrhage, based on case reports. Its pathologic characteristics typically include bilateral gland involvement with extensive necrosis of all 3 cortical layers and of medullary adrenal cells. Retrograde migration of medullary cells into the zona fasciculata, widespread hemorrhage into the adrenal gland that may extend into the perirenal fat, and, frequently, adrenal vein thrombosis may occur.

Adrenal hemorrhage has been reported in 0.3-1.8% of unselected cases in autopsy studies, although extensive bilateral adrenal hemorrhage may be present in 15% of individuals who die of shock 2.

Acute adrenal insufficiency (adrenal crisis or Addisonian crisis) may occur in association with extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, and it is uniformly fatal if unrecognized and untreated. In contrast, unilateral adrenal hemorrhage is not associated with acute adrenal insufficiency.

Patients with adrenal hemorrhage may die because of underlying disease or diseases associated with adrenal hemorrhage, despite treatment with stress-dose glucocorticoids. Overall, adrenal hemorrhage is associated with a 15% mortality rate, which varies according to the severity of the underlying illness predisposing to adrenal hemorrhage. For example, patients with Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (adrenal hemorrhage occurring in sepsis, most frequently meningococcal) have a 55-60% mortality rate 3.

Although adrenal hemorrhage may occur in people of any age, most patients with nontraumatic, extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage are aged 40-80 years at the time of the acute event. In contrast, patients with traumatic adrenal hemorrhage typically are in the second to third decade of life.

Most patients with Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome are in the pediatric age group, although adults have infrequently been affected.

Adrenal hemorrhage in neonates is a well-described entity and has even been diagnosed in utero.

Chronic adrenal insufficiency occurs in most patients who survive extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, necessitating long-term glucocorticoid replacement. In contrast, the need for mineralocorticoid replacement is variable. Androgen replacement therapy may also be beneficial in women with chronic adrenal insufficiency. Rare case reports exist of patients who had complete recovery of adrenal function after an episode of extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage and acute adrenal insufficiency.

Adrenal hemorrhage causes

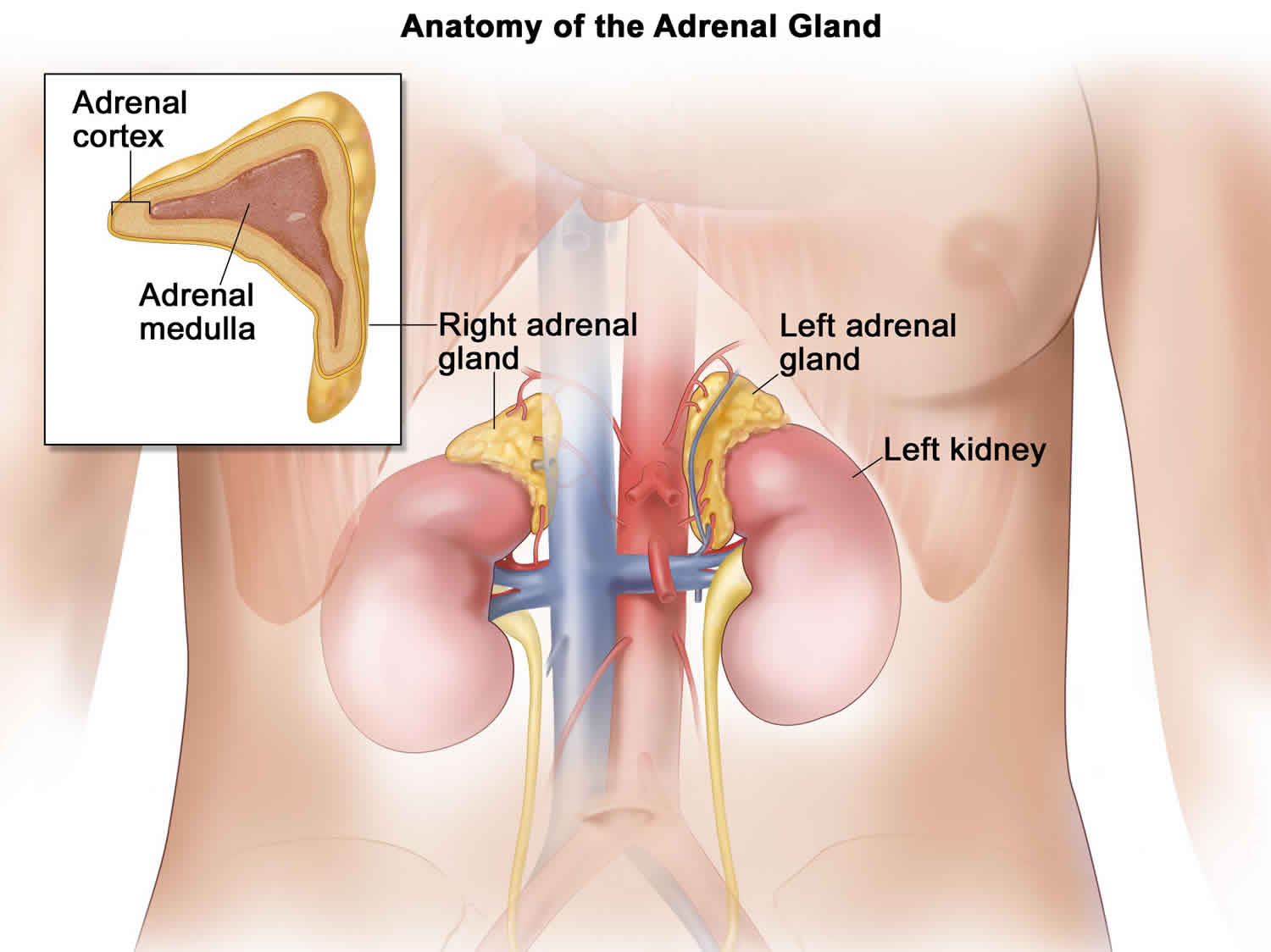

Although the causes leading to adrenal hemorrhage are unclear in nontraumatic cases, available evidence has implicated adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), adrenal vein spasm and thrombosis, and the normally limited venous drainage of the adrenal in the pathogenesis of adrenal hemorrhage 2.

The adrenal gland has a rich arterial supply, in contrast to its limited venous drainage, which is critically dependent on a single vein. Furthermore, in stressful situations, ACTH secretion increases, which stimulates adrenal arterial blood flow that may exceed the limited venous drainage capacity of the organ and lead to hemorrhage.

In addition, adrenal vein spasm induced by high catecholamine levels secreted in stressful situations and by adrenal vein thrombosis induced by coagulopathies may lead to venous stasis and hemorrhage. Adrenal vein thrombosis has been found in several patients with adrenal hemorrhage, and it may occur in association with sepsis, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia 4). primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Regardless of the precise mechanisms, extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage commonly leads to acute adrenal insufficiency and adrenal crisis, unless it is recognized and treated promptly.

Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage causes

In at least 50% of cases, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage is associated with an acute, stressful illness (eg, infection, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, complications of pregnancy) or event (eg, surgery or invasive procedure). Other frequent associations include hemorrhagic diatheses (eg, anticoagulant use, thrombocytopenia), thromboembolic disease (including antiphospholipid antibody syndrome), blunt trauma, and ACTH therapy. In addition, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage has been reported in patients with tuberculosis, amyloidosis, or metastatic tumors involving the adrenals, including lung adenocarcinoma. A multicenter, hospital-based, case-control study identified thrombocytopenia, heparin exposure, and sepsis as the major risk factors for the development of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

- Infections associated with extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage are diverse; they include sepsis, wound infections, pneumonia, pseudomembranous colitis, influenza, varicella, and malaria.

- Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (purpura fulminans) represents hemorrhagic necrosis of several organs, including adrenal hemorrhage, in the setting of overwhelming sepsis. The syndrome frequently is characterized by a distinctly hemorrhagic skin rash. Although Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome originally was recognized in association with meningococcal disease, which still accounts for 80% of cases, the syndrome also has been associated with other bacterial pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae (group B), Salmonella choleraesuis, Pasteurella multocida, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, and Plesiomonas shigelloides 5.

- Congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, inflammatory bowel disease, acute pancreatitis, and cirrhosis also have been associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage 6.

- Obstetric causes of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage include toxemia of pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, antepartum or postpartum hemorrhage, twisted ovarian cyst (in pregnancy), and primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage during pregnancy has rarely been described 7.

- Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, hip joint replacement, intracranial surgery, and hepatic arterial chemoembolization are procedures associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage 8. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia may predispose to adrenal hemorrhage in some of these patients.

- Hemorrhagic diatheses, including anticoagulant use, thrombocytopenia, and vitamin K deficiency have been associated with approximately one third of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage cases. Heparin use accounts for the majority of cases of anticoagulant-associated, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. In such cases, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage occurs despite the fact that the activated partial thromboplastin time is almost invariably therapeutic, and adrenal hemorrhage represents an isolated event without evidence of bleeding elsewhere. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) was found to underlie several bilateral adrenal hemorrhage cases, although the precise role of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) in the pathogenesis of heparin-induced adrenal hemorrhage has not been fully elucidated 9.

- Arterial (eg, pulmonary embolism, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial embolism) and venous (eg, deep venous thrombosis, superficial thrombophlebitis) causes have been associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in one third of cases. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (either primary or secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus) has been associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage 10.

- Blunt trauma of diverse etiologies, ranging from motor vehicle accidents to a truck ride over a bumpy road, has been associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

- Underlying adrenal pathologic conditions, including granulomatous diseases, amyloidosis, and metastatic cancer (eg, lung or gastric adenocarcinoma), have been associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

- Treatment with ACTH for multiple sclerosis or inflammatory bowel disease has in some cases been associated with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

Unilateral adrenal hemorrhage causes

Unilateral adrenal hemorrhage most frequently is caused by blunt abdominal trauma (traumatic adrenal rupture), but it also has occurred in liver transplant recipients and in patients with primary adrenal or metastatic tumors. In addition, unilateral adrenal hemorrhage is associated, albeit infrequently, with otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy, neurofibromatosis 1, or long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. There have been rare reports of idiopathic, spontaneous, unilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

In a retrospective study of 23 patients with adrenal hemorrhage (including 22 with a unilateral condition), Karwacka et al reported that risk factors could not be determined in 13 patients, while risk factors in the rest of the cohort included trauma (5 patients), sepsis (1 patient; bilateral adrenal hemorrhage), concomitant neoplastic disease (2 patients), both anticoagulant drug use and lung cancer (1 patient), and both trauma and chronic oral anticoagulation (1 patient) 11.

- Unilateral adrenal hemorrhage secondary to blunt trauma more often involves the right adrenal. Liver hematomas and rib fractures commonly occur in these patients as well. Unilateral adrenal hemorrhage occurs in 2% of patients with penetrating trauma.

- Right adrenal hemorrhage was found in 2% of liver transplant recipients in one study, and it also was reported in 10% of children dying early after orthotopic liver transplantation. In these patients, intraoperative ligation of the right adrenal vein, performed after a limited resection of the recipient’s inferior vena cava, has sometimes resulted in venous infarction and adrenal hemorrhage.

- Unilateral adrenal hemorrhage was described in patients with primary adrenal or metastatic tumors, representing hemorrhagic tumor infarction. Primary adrenal tumors associated with adrenal hemorrhage include adrenal adenomas, adrenocortical carcinomas, and pheochromocytomas. In addition, adrenal hemorrhage has been described in patients with metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma or with lung or gastric adenocarcinoma 12.

- In isolated cases, unilateral adrenal hemorrhage may occur in association with long-term NSAID, otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy, and neurofibromatosis 1 13.

- Idiopathic, unilateral adrenal hemorrhage is a rare entity that either may have an acute presentation (eg, idiopathic adrenal rupture) or may present as an asymptomatic adrenal mass 14.

Adrenal hemorrhage symptoms

Symptoms of adrenal hemorrhage are nonspecific; they include abdominal, lumbar, pelvic, or thoracic pain and symptoms of acute adrenal insufficiency, such as fatigue, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Symptoms associated with the underlying condition(s) also may be present. Rarely, adrenal hemorrhage is entirely asymptomatic, presenting as an incidental finding on imaging studies.

Bleeding into the adrenal glands causes adrenal crisis, in which not enough adrenal hormones are produced. This leads to symptoms such as:

- Dizziness, weakness

- Very low blood pressure

- Very fast heart rate

- Confusion or coma

Pain that is nonspecific in location and quality is the most consistent feature of adrenal hemorrhage.

- Nonspecific pain occurred in 65-85% of published cases.

- It can occur predominantly in the epigastrium, flank, upper or lower back, pelvis, or precordium or elsewhere in the thorax.

- Left shoulder pain may occur in association with abdominal pain, likely because of diaphragmatic irritation.

Fatigue, weakness, dizziness, arthralgias, myalgias, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which are present in approximately 50% of extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage cases, are indicative of acute adrenal insufficiency.

Symptoms of the underlying condition(s) predisposing to adrenal hemorrhage may be present. For example, patients with Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome often experience prodromic, nonspecific symptoms, including malaise, headache, dizziness, cough, arthralgias, and myalgias.

Adrenal hemorrhage may be present in approximately 2 of 1000 newborn infants and may arise spontaneously or in association with birth trauma, asphyxia, sepsis, or hemorrhagic diathesis.

Physical findings in patients with adrenal hemorrhage are nonspecific and vary depending on the extent of adrenal hemorrhage, the bleeding rate, and the underlying cause, as well as according to whether the adrenal hemorrhage is bilateral or unilateral.

Fever [ie, temperature > 100.4 °F (38 ºC)] is present in 50-70% of patients with adrenal hemorrhage, representing the most frequent finding in adrenal hemorrhage.

- In reported cases, temperature may range from low-grade fever to high fever with chills.

- In the setting of adrenal hemorrhage, fever may be associated with adrenal insufficiency, the hematoma itself, or the underlying cause of adrenal hemorrhage.

Tachycardia has been reported in approximately 40-50% of patients early in the course of extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, and without aggressive therapy, it may progress to shock.

Orthostatic hypotension is present in approximately 20% of patients with extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. This is an early finding that, if there is no specific intervention, usually leads to supine hypotension and shock.

Because shock occurs only late in the course of extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, its absence should not be used to exclude this diagnosis.

- In addition to acute adrenal insufficiency, shock in patients with extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage may be caused by 1 or more underlying conditions, including sepsis, cardiovascular causes (commonly myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism), or hypovolemia.

- In Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, activation of several cytokine mediators appears to lead to sepsis and shock. Whether acute adrenal insufficiency has a significant role in the pathogenesis of the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome remains unclear and debatable.

Hypertension has been reported rarely in patients with unilateral adrenal hemorrhage; in one patient it was accompanied by headache and dizziness, leading to an erroneous diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

Weight loss is very uncommon, but it may occur in cases of adrenal hemorrhage that are recognized several weeks after the event. These patients have a subacute presentation of adrenal insufficiency in association with adrenal hemorrhage, instead of acute adrenal crisis.

Skin hyperpigmentation has been reported rarely in adrenal hemorrhage cases. Its presence indicates late recognition of adrenal insufficiency in association with adrenal hemorrhage.

A characteristic skin rash with a typical evolution occurs in approximately 75% of patients with Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome.

- In its early stages, the rash consists of small, pink macules or papules.

- These are rapidly followed by petechial lesions, which gradually transform into large, purpuric, coalescent plaques in late stages of the disease.

Signs of acute abdomen, including guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness, have been reported in 15-20% of patients. This relative paucity of physical findings on abdominal examination is likely secondary to the retroperitoneal location of the adrenals.

Confusion and disorientation are present in 20-40% of patients. These findings are also nonspecific, because they may be associated with acute adrenal insufficiency or with the underlying condition(s) precipitating adrenal hemorrhage.

Adrenal hemorrhage diagnosis

Tests that may be ordered to help diagnose acute adrenal crisis include:

- ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test

- Cortisol blood test

- Blood sugar

- Potassium blood test

- Sodium blood test

- Blood pH test

- Percutaneous biopsy is helpful in establishing the presence of metastatic disease in cases of adrenal hemorrhage in which suggestive features appear on CT scans.

Laboratory Studies

Complete blood count (CBC) and differential generally are obtained to assist with therapeutic decisions, although these test results are nonspecific.

- A significant decrease in hematocrit (at least 4%) or hemoglobin (at least 2 g/dL) occurs in approximately one half of patients with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

- Leukocytosis frequently occurs in patients with adrenal hemorrhage, and it may be associated with the underlying cause of adrenal hemorrhage. Eosinophilia is present in only a small percentage of patients with adrenal hemorrhage.

Serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and plasma glucose may be of limited diagnostic use, but they also should be obtained to assist with patient management.

- Hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and prerenal azotemia are present in approximately 50% of patients with extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. Mild hypercalcemia may rarely occur. Although the combination of low serum sodium and high serum potassium is suggestive of adrenal insufficiency in the appropriate clinical setting, their absence never should exclude this diagnosis.

- Hypoglycemia may occur in patients with adrenal hemorrhage and adrenal insufficiency, but it rarely is severe.

Serum cortisol, plasma ACTH, serum aldosterone, and plasma renin activity (PRA) always should be obtained in suspected adrenal hemorrhage cases, because they provide important information on adrenal function.

- In an acutely ill patient, the combination of increased plasma ACTH and low, or even low-normal (ie, < 13 mcg/dL), serum cortisol is highly suggestive of glucocorticoid deficiency due to primary adrenal insufficiency. Conversely, a serum cortisol of over 25 mcg/dL in an acutely ill patient excludes glucocorticoid deficiency. The combination of low serum aldosterone and increased PRA suggests mineralocorticoid deficiency.

- In order to provide useful diagnostic information, blood samples for these tests should be obtained before glucocorticoid administration, because several exogenous glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone and prednisone, but not dexamethasone) cross-react with endogenous cortisol in radioimmunoassay.

- Because results are not available immediately, these tests are not helpful in the acute setting, but they provide retrospective diagnostic information.

The short cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation test confirms the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency.

- This test involves the bolus intravenous or intramuscular administration of the ACTH analog cosyntropin (Cortrosyn, 250 mcg) and serum collection 1 hour after cosyntropin administration for cortisol assay. A peak serum cortisol of over 20 mcg/dL (1 h after cosyntropin administration) indicates normal adrenal response in a nonstressed individual.

- Although the normal adrenal response to cosyntropin has not been defined precisely in acutely ill patients, individuals with bilateral adrenal hemorrhage and clinical evidence of adrenal insufficiency have a markedly blunted adrenal response, according to the above criteria, in this test.

- Measurement of the aldosterone response to cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) administration has been advocated in order to assess mineralocorticoid reserve. Serum samples are obtained immediately before and 30 minutes after the administration, as above, of intravenous cosyntropin. Either a peak serum aldosterone of over 16 ng/dL or a rise in serum aldosterone of at least 4 ng/dL indicates a normal adrenal response.

- Although the short cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation test is the criterion standard for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency, its performance may not be practical in the acute setting, particularly in a hypotensive or otherwise unstable patient. In these cases, only basal cortisol and ACTH levels need to be obtained before urgent glucocorticoid administration, and the more definitive Cortrosyn stimulation test can be performed after the patient has been stabilized. Alternatively, because the presence of dexamethasone does not interfere with cortisol immunoassays, this medication can be administered to stabilize the condition of a patient with suspected adrenal insufficiency, before the short Cortrosyn stimulation test is performed.

- Because the results of the short cosyntropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation test are not available immediately, this test is not helpful in the acute setting to guide management decisions, but it provides retrospective confirmation of adrenal insufficiency.

Imaging Studies

CT scanning

Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the adrenals (thin slice) is the study of choice for demonstrating adrenal hemorrhage in the acute setting 15. However, it is practical only in hemodynamically stable patients.

CT scanning of patients with adrenal hemorrhage shows adrenal enlargement that may be asymmetrical in cases of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. The glands become rounded or oval shaped and have high attenuation (50-90 Hounsfield units) without contrast enhancement in the acute setting.

In cases of unilateral, traumatic adrenal hemorrhage, a streaky appearance of the perirenal fat frequently is observed posterior to the gland 16. This finding is not specific to traumatic adrenal hemorrhage, because it also has been observed in patients with adrenal hemorrhage and metastatic tumors to the adrenals. Extension of the hemorrhage into the perirenal space, with perinephric hematoma formation, has been observed in patients with metastatic disease.

Associated findings may include a mixed-density, inhomogeneous mass in patients with primary or metastatic cancer. Significant contrast enhancement further suggests the presence of an associated lesion (such as pheochromocytoma or metastatic tumor).

Several weeks after the acute adrenal hemorrhage, CT scanning shows a gradual decrease in adrenal size and attenuation. In addition, the adrenals may have a cystic appearance.

Several months after the acute event, CT scanning of the adrenals shows progressive atrophy, with the variable appearance of calcifications. The presence of adrenal calcifications does not invariably indicate a previous episode of adrenal hemorrhage, because this finding also is associated with adrenal cysts, adrenocortical adenomas and carcinomas, pheochromocytomas, neuroblastomas (only in children), metastatic tumors, and granulomatous diseases, including tuberculosis and histoplasmosis.

A study by Tan and Sutherland suggested that signs of adrenal congestion (adrenal gland thickening, periadrenal fat stranding) on CT scanning can predict subsequent nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhaging. The study involved four patients with nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage, who were compared with 12 randomly selected intensive care patients 17.

Recognizing that adrenal hematomas with a masslike configuration can be mistaken for adrenal neoplasms, leading to surgical resection, Rowe et al described the CT-scan characteristics of five adrenal hematomas. The lesions were well-defined, with an ovoid morphology, an average maximum diameter of 8.9 cm, and greatly varying attenuation on noncontrast CT scan. Peripheral enhancement in four of the hematomas was either thin and somewhat uniform or heterogeneous and irregular. The five lesions did not invade periadrenal fat or adjacent organs 18.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to help exclude the presence of malignant tumors or pheochromocytomas, and it may provide an estimate of the age of the hematoma 19. Less experience with the use of MRI in adrenal hemorrhage exists in comparison with CT scanning.

Acutely (ie, 24-72 h after onset), the adrenals are enlarged. Adrenal hemorrhage appears isointense with normal liver and muscle on T1-weighted images and appears hyperintense to the liver on T2-weighted images. Stranding of the perirenal and even subcutaneous fat has been observed in T2-weighted images in traumatic adrenal hemorrhage cases.

Subacutely (ie, approximately 3-7 d after onset), adrenal hemorrhage shows intermediate intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images. This appearance has been associated with the presence of deoxyhemoglobin in the adrenal hemorrhagic area. In addition, a hyperintense ring frequently is observed outlining the adrenals (on T1- and T2-weighted images). This hyperintense ring gradually may fill in centrally, and it appears to be secondary to the presence of free methemoglobin.

At a more chronic stage (ie, several wk after onset), MRI shows a decrease in adrenal size. In addition, adrenal hemorrhagic areas become hyperintense with a hypointense rim on T1- and T2-weighted images. The centrally located, high signal intensity may be secondary to the presence of free methemoglobin, and the hypointense rim has been associated with the presence of hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the fibrous capsule. Furthermore, necrotic areas in the adrenal hemorrhagic area may create a more heterogeneous appearance, with areas of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images.

In a suspected adrenal hemorrhage case, the lack of enhancement after gadolinium–diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (Gd-DTPA) administration and the above-outlined evolution of the appearance of the adrenals confirm the diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage and help to exclude the presence of tumor.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonographic examination of the adrenals (including Doppler ultrasonography) is quite helpful in neonatal adrenal hemorrhage cases, and it may reveal the presence of adrenal hemorrhage in utero.

In older children or adults, ultrasonographic examination may be employed at the bedside, although it is operator dependent and may be limited by large body habitus.

Ultrasonographic imaging of adrenal hemorrhage reveals hyperechoic masses that contain a central echogenic area in the adrenal glands. Several weeks after the acute event, the central echogenicity associated with adrenal hemorrhage decreases as the hematomas become cystic.

Histologic Findings

Examination of the adrenals in adrenal hemorrhage cases typically reveals extensive hemorrhagic necrosis involving all 3 adrenal cortical cell layers, in addition to adrenal medullary cell necrosis. The hemorrhage may extend into the perirenal fat and the perirenal space.

Other common findings include adrenal vein thrombosis and the retrograde migration of medullary cells into the zona fasciculata. In contrast, vasculitis rarely has been observed in cases of adrenal hemorrhage, suggesting that it has a limited role in the pathogenesis of adrenal hemorrhage.

At a more chronic stage, the hematoma becomes organized as a fibrous capsule that forms around the adrenal hemorrhagic area. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages are present in the capsule and digest cell debris. In the months following acute adrenal hemorrhage, fibrous tissue gradually replaces the hemorrhagic areas.

Adrenal hemorrhage treatment

In patients with suspected acute adrenal hemorrhage, evaluation should take place in an inpatient setting, because acute adrenal insufficiency may occur. However, most of these patients are acutely ill and already are in the hospital at the time of acute adrenal hemorrhage.

In asymptomatic patients presenting with an adrenal mass or calcifications, outpatient evaluation is appropriate.

Medical therapies are used to replace adrenal function, to provide vital function support as needed, to treat the underlying condition(s), and to correct fluid, electrolyte, and red cell mass deficits.

Immediately after a serum sample for cortisol assay has been obtained, but without awaiting biochemical confirmation, glucocorticoids should be urgently administered to patients with suspected acute, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in order to prevent or treat acute adrenal insufficiency.

In acutely ill patients, supportive therapy and specific treatments for the underlying condition(s) must be provided urgently as well.

After the acute adrenal hemorrhagic event, long-term glucocorticoid replacement with or without mineralocorticoid replacement therapy may be necessary, based on the results of adrenal function testing.

Diet

Critically ill patients with suspected adrenal hemorrhage are kept on nothing by mouth (NPO) status.

Patients with acute adrenal hemorrhage also may be kept nothing by mouth, depending on the presence of symptoms, such as vomiting.

In cases of chronic adrenal hemorrhage complicated by adrenal insufficiency, patients must maintain adequate hydration and salt intake. Liberal salt intake is contraindicated in the presence of hypertension, congestive heart failure, or renal failure.

Activity

Patients with suspected acute adrenal hemorrhage are kept on bed rest.

Activity is unrestricted after resolution of the acute event; however, patients must receive appropriate adrenal replacement therapy. Depending on the underlying condition(s), activity restrictions may still be necessary.

Surgical Care

Adrenalectomy (open or laparoscopic) may be performed.

- Surgery generally is not required in cases of nontraumatic adrenal hemorrhage, except in patients with primary adrenal tumors or in rare cases, of extensive retroperitoneal hemorrhage secondary to adrenal hemorrhage.

- In traumatic adrenal hemorrhage cases, surgery may be necessary for the treatment of associated injuries, the exploration of penetrating wounds, or the control of bleeding.

- Vella A, Nippoldt TB, Morris JC 3rd. Adrenal hemorrhage: a 25-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001 Feb. 76(2):161-8.[↩]

- Adrenal hemorrhage. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/126806-overview[↩][↩]

- Tormos LM, Schandl CA. The Significance of Adrenal Hemorrhage: Undiagnosed Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome, A Case Series. J Forensic Sci. 2013 Mar 4.[↩]

- Ketha S, Smithedajkul P, Vella A, Pruthi R, Wysokinski W, McBane R. Adrenal haemorrhage due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost. 2013 Feb 7. 109(4[↩]

- Adem PV, Montgomery CP, Husain AN, et al. Staphylococcus aureus sepsis and the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in children. N Engl J Med. 2005 Sep 22. 353(12):1245-51.[↩]

- Pianta M, Varma DK. Bilateral spontaneous adrenal haemorrhage complicating acute pancreatitis. Australas Radiol. 2007 Apr. 51(2):172-4.[↩]

- Kadhem S, Ebrahem R, Munguti C, Mortada R. Spontaneous Unilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage in Pregnancy. Cureus. 2017 Jan 13. 9 (1):e977.[↩]

- Gutenberg A, Lange B, Gunawan B, et al. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage: a little-known complication of intracranial tumor surgery. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2007 Jun. 106(6):1086-8.[↩]

- Rosenberger LH, Smith PW, Sawyer RG, Hanks JB, Adams RB, Hedrick TL. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage: The unrecognized cause of hemodynamic collapse associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Crit Care Med. 2011 Apr. 39(4):833-8.[↩]

- Ramon I, Mathian A, Bachelot A, et al. Primary Adrenal Insufficiency Due to Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage-Adrenal Infarction in the Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Long-Term Outcome of 16 Patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Jun 19.[↩]

- Karwacka IM, Obolonczyk L, Sworczak K. Adrenal hemorrhage: a single center experience and literature review. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018 May. 27 (5):681-7.[↩]

- Vasinanukorn P, Rerknimitr R, Sriussadaporn S, et al. Adrenal hemorrhage as the first presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Intern Med. 2007. 46(21):1779-82.[↩]

- Gavrilova-Jordan L, Edmister WB, Farrell MA, et al. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage during pregnancy: a review of the literature and a case report of successful conservative management. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005 Mar. 60(3):191-5.[↩]

- Marti JL, Millet J, Sosa JA, Roman SA, Carling T, Udelsman R. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage with associated masses: etiology and management in 6 cases and a review of 133 reported cases. World J Surg. 2012 Jan. 36(1):75-82.[↩]

- Shah HR, Love L, Williamson MR, et al. Hemorrhagic adrenal metastases: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989 Jan-Feb. 13(1):77-81.[↩]

- Sinelnikov AO, Abujudeh HH, Chan D, et al. CT manifestations of adrenal trauma: experience with 73 cases. Emerg Radiol. 2007 Mar. 13(6):313-8.[↩]

- Tan GX, Sutherland T. Adrenal congestion preceding adrenal hemorrhage on CT imaging: a case series. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016 Feb. 41 (2):303-10.[↩]

- Rowe SP, Mathur A, Bishop JA, et al. Computed Tomography Appearance of Surgically Resected Adrenal Hematomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2016 Nov/Dec. 40 (6):892-895.[↩]

- Bhatia KS, Ismail MM, Sahdev A, et al. (123)I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy for the detection of adrenal and extra-adrenal phaeochromocytomas: CT and MRI correlation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008 Apr 3.[↩]