What is allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis also known as hay fever, is inflammation of the inside of your nose caused by an allergen, such as pollen, dust, dust mites, insects, molds, or flakes of skin from certain animals (animal dander) and saliva shed by cats . Allergic rhinitis symptoms include runny nose (rhinorrhea), sneezing, and nasal congestion, nasal obstruction, nasal itch (nasal pruritus), itchy eyes and sinus pressure 1. If symptoms are uncontrolled they can affect your sinuses, throat, voice box and lower airways as well as your eyes and middle ear. Rhinitis means ‘inflammation of the nose’, whilst the term allergic describes ‘a normal but exaggerated response to a substance’. Allergies are your immune system’s incorrect response to allergens (foreign substances). Exposure to what is normally a harmless substance causes the immune system to react as if the substance is harmful. People may experience a number of allergic symptoms including itchy, watery nose and eyes, asthma symptoms, eczema or hives and allergic shock (also called anaphylaxis or anaphylactic shock). Allergic rhinitis may be perennial allergic rhinitis, which means symptoms are present throughout the year, or seasonal allergic rhinitis, with symptoms peaking during the months of spring and summer when pollen levels are at their highest.

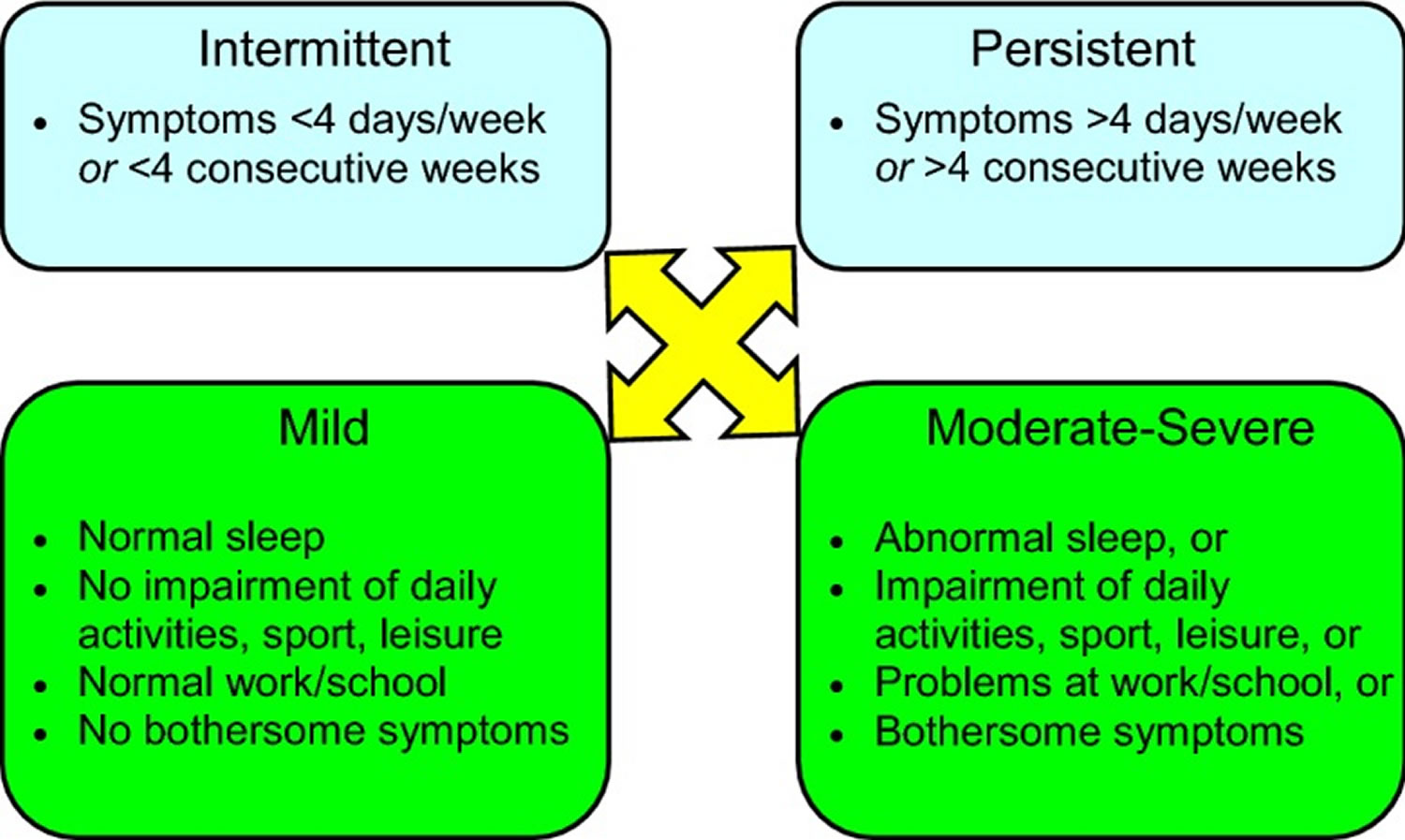

Traditionally, allergic rhinitis has been categorized as seasonal (occurs during a specific season) or perennial (occurs throughout the year) 2. However, not all patients fit into this classification scheme. For example, some allergic triggers, such as pollen, may be seasonal in cooler climates, but perennial in warmer climates, and patients with multiple “seasonal” allergies may have symptoms throughout most of the year 3. Therefore, allergic rhinitis is now classified according to symptom duration (intermittent or persistent) and severity (mild, moderate or severe) (see Figure 1) 4. The Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines have classified “intermittent” allergic rhinitis as symptoms that are present less than 4 days per week or for less than 4 consecutive weeks, and “persistent” allergic rhinitis as symptoms that are present more than 4 days/week and for more than 4 consecutive weeks 4. Symptoms are classified as mild when patients have no impairment in sleep and are able to perform normal activities (including work or school). Symptoms are categorized as moderate/severe if they significantly affect sleep or activities of daily living, and/or if they are considered bothersome. It is important to classify the severity and duration of symptoms as this will guide the management approach for individual patients 5.

In recent years, two additional types of rhinitis have been classified—occupational rhinitis and local allergic rhinitis 6.

Figure 1. Allergic rhinitis classification

[Source 6 ]There is also a strong relationship between allergic rhinitis and asthma; patients with allergic rhinitis are three times more likely to develop asthma and effective treatment of allergic rhinitis has beneficial effects on asthma.

Allergic rhinitis is caused by the immune system reacting to an allergen as if it were harmful. This results in cells releasing a number of chemicals that cause the inside layer of your nose (the mucous membrane) to become swollen and excessive levels of mucus to be produced.

Common allergens that cause allergic rhinitis include pollen – this type of allergic rhinitis is known as hay fever – as well as mold spores, house dust mites, and flakes of skin or droplets of urine or saliva from certain animals.

Allergic rhinitis is a very common condition affecting many people worldwide, estimated to affect around one in every five people in the US.

Visit your doctor if the symptoms of allergic rhinitis are disrupting your sleep, preventing you carrying out everyday activities, or adversely affecting your performance at work or school.

A diagnosis of allergic rhinitis will usually be based on your symptoms and any possible triggers you may have noticed. If the cause of your condition is uncertain, you may be referred for allergy testing.

If your condition is mild, you can also help reduce the symptoms by taking over-the-counter medications, such as non-sedating antihistamines, and by regularly rinsing your nasal passages with a salt water solution to keep your nose free of irritants.

See your doctor for advice if you’ve tried taking these steps and they haven’t helped. They may prescribe a stronger medication, such as a nasal spray containing corticosteroids.

Further problems

Allergic rhinitis can lead to complications in some cases. These include:

- nasal polyps – abnormal but non-cancerous (benign) sacs of fluid that grow inside the nasal passages and sinuses

- sinusitis – an infection caused by nasal inflammation and swelling that prevents mucus draining from the sinuses

- middle ear infections – infection of part of the ear located directly behind the eardrum

These problems can often be treated with medication, although surgery is sometimes needed in severe or long-term cases.

Allergic rhinitis key points 6:

- Allergic rhinitis is linked strongly with asthma and conjunctivitis.

- Allergen skin testing is the best diagnostic test to confirm allergic rhinitis.

- Intranasal corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for most patients that present to physicians with allergic rhinitis.

- Allergen immunotherapy is an effective immune-modulating treatment that should be recommended if pharmacologic therapy for allergic rhinitis is not effective or is not tolerated.

See your doctor if:

- You can’t find relief from your allergic rhinitis symptoms

- Allergy medications don’t provide relief or cause annoying side effects

- You have another condition that can worsen allergic rhinitis symptoms, such as nasal polyps, asthma or frequent sinus infections

Many people — especially children — get used to allergic rhinitis symptoms, so they might not seek treatment until the symptoms become severe. But getting the right treatment might offer relief.

Why is it important to treat allergic rhinitis?

Rhinitis is often regarded as a trivial problem, but studies have shown that it affects quality of life. It disturbs sleep, impairs daytime concentration and ability to carry out tasks, causes people to miss work or school and has been shown to affect examination results.

People who have allergic rhinitis are at increased risk of developing asthma as the upper airway affects the lower part of the airway leading to the lungs. Many asthmatics also have rhinitis which may have an allergic trigger. Asthma can be better controlled with fewer hospital admissions if rhinitis is effectively treated.

Who’s most at risk for allergic rhinitis?

It isn’t fully understood why some people become oversensitive to allergens, although you’re more likely to develop an allergy if there’s a history of allergies in your family.

If this is the case, you’re said to be “atopic”, or to have “atopy”. People who are atopic have a genetic tendency to develop allergic conditions. Their increased immune response to allergens results in increased production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies.

Environmental factors may also play a part. Studies have shown certain things may increase the chance of a child developing allergies, such as growing up in a house where people smoke and being exposed to dust mites at a young age.

It’s difficult to completely avoid potential allergens, but you can take steps to reduce exposure to a particular allergen you know or suspect is triggering your allergic rhinitis. This will help improve your symptoms.

What is perennial (all year round) allergic rhinitis?

People with all year round allergic rhinitis symptoms can easily mistake it for a persistent or frequent cold. Perennial allergic rhinitis is characterized primarily by nasal symptoms including watering or congestion of the nose and sneezing. It occurs due to an exaggerated response to an environmental trigger which results in inflammation of the lining of the nose. Perennial allergic rhinitis is similar to hay fever, however, the substances which cause the allergic reaction are present all year round. The symptoms are often triggered by allergens in the home such as those from house dust mites, pets and indoor molds and industrial dusts and fumes.

What is occupational rhinitis?

Occupational rhinitis can be allergic rhinitis or a non-allergic rhinitis arising from airborne substances in the work environment 7 and examples of this could be latex, flour (factory workers, food-processing workers, pastry chefs), plants (arborist), animals (including laboratory animals, veterinarians, farmers and abattoir), glutaraldehyde, chlorine, ammonia (workers in various manufacturing industries) 7. According to a recent published report there are over 300 agents which can cause occupational rhinitis. Occupational rhinitis often improves when away from the work place (i.e., when on holiday). It is important to identify occupational rhinitis as it can progress to irreversible asthma if exposure continues 8.

What is local allergic rhinitis?

Local allergic rhinitis is a clinical entity characterized by a localized allergic response in the nasal mucosa in the absence of evidence of systemic atopy 9. By definition, patients with local allergic rhinitis have negative skin tests and/or in vitro tests for IgE, but have evidence of local IgE production in the nasal mucosa; these patients also react to nasal challenges with specific allergens 10.

The symptoms of local allergic rhinitis are similar to those provoked in patients with allergic rhinitis, and the assumption is that local allergic rhinitis is an IgE-mediated disease based on both clinical findings and the detection of specific IgE in the nasal mucosa. To date, there is no evidence to suggest that local allergic rhinitis is a precursor to allergic rhinitis since follow-up does not show the evolution to typical allergic rhinitis in these patients 11; however, patient follow-up may not have been long enough to detect this disease evolution. The implications for treatment of local allergic rhinitis are not well understood at this time, although some evidence suggests that allergen immunotherapy may be effective in this type of rhinitis 9.

Seasonal allergic rhinitis

Seasonal allergic rhinitis is also called hayfever that occurs in late summer or spring. Seasonal allergic rhinitis (hayfever) occurs due to an exaggerated response to an environmental trigger which results in inflammation of the lining of the nose. Seasonal allergic rhinitis (hayfever) is characterized by irritation and congestion or watering of the nose, itchy eyes, ears and throat, and sneezing. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is caused by airborne allergens from grasses, trees, weeds, plants and outdoor molds which are wind pollinated. Grass pollen is the most common trigger of hay fever and it is for this reason that allergic rhinitis is often referred to as hay fever. Bright flowers whose pollination is by insects are unlikely to cause allergy. In the case of seasonal allergic rhinitis, pollen is the most common trigger, hence symptoms are usually experienced during the spring and summer months when the pollen season is at its peak. Hypersensitivity to ragweed, not hay, is the primary cause of seasonal allergic rhinitis in 75 percent of all Americans who suffer from this seasonal disorder. People with sensitivity to tree pollen have symptoms in late March or early April; an allergic reaction to mold spores occurs in October and November as a consequence of falling leaves. While some people with hay fever react to one type of pollen during the ‘season’, and then feel better later in the year, it is also possible to be affected by more than one type of pollen or airborne allergen, leading to many months of rhinitis.

Allergic rhinitis symptoms

Allergic rhinitis symptoms can include:

- Sneezing

- Itchy nose/itchy palate/itchy throat

- Blocked nose/stuffy nose/ nasal congestion

- Runny nose (usually with clear fluid)/ nasal discharge

- Red/itchy/watery eyes (that can become very sore or infected with frequent rubbing)

- Post nasal drip (the sensation of mucus running down the back of the throat)

- Cough

- Wheezing/asthma symptoms/tight chest/breathlessness

- Sinus inflammation/pain

- Feeling of itch in ear/ear blockage

- Nose bleeds – This may be due to the lining of the nose being itchy and is often rubbed or scratched.

Your allergic rhinitis signs and symptoms may start or worsen at a particular time of year. Triggers include:

- Tree pollen, which is common in early spring.

- Grass pollen, which is common in late spring and summer.

- Ragweed pollen, which is common in fall.

- Dust mites, cockroaches and dander from pets can be bothersome year-round (perennial). Symptoms caused by dander might worsen in winter, when houses are closed up.

- Spores from indoor and outdoor fungi and molds are considered both seasonal and perennial.

Allergic rhinitis typically causes cold-like symptoms, such as sneezing, itchiness and a blocked or runny nose. These symptoms usually start soon after being exposed to an allergen.

Some people only get allergic rhinitis for a few months at a time because they’re sensitive to seasonal allergens, such as tree or grass pollen. Other people get allergic rhinitis all year round.

Most people with allergic rhinitis have mild symptoms that can be easily and effectively treated. But for some symptoms can be severe and persistent, causing sleep problems and interfering with everyday life.

The symptoms of allergic rhinitis occasionally improve with time, but this can take many years and it’s unlikely that the condition will disappear completely.

Allergic rhinitis complications

If you have allergic rhinitis, there’s a risk you could develop further problems.

A blocked or runny nose can result in difficulty sleeping, drowsiness during the daytime, irritability and problems concentrating. Allergic rhinitis can also make symptoms of asthma worse.

The inflammation associated with allergic rhinitis can also sometimes lead to other conditions, such as nasal polyps, sinusitis and middle ear infections.

Problems that may be associated with allergic rhinitis include:

- Reduced quality of life. Hay fever can interfere with your enjoyment of activities and cause you to be less productive. For many people, hay fever symptoms lead to absences from work or school.

- Poor sleep. Hay fever symptoms can keep you awake or make it hard to stay asleep, which can lead to fatigue and a general feeling of being unwell (malaise).

- Worsening asthma. Hay fever can worsen signs and symptoms of asthma, such as coughing and wheezing.

- Sinusitis. Prolonged sinus congestion due to hay fever may increase your susceptibility to sinusitis — an infection or inflammation of the membrane that lines the sinuses.

- Ear infection. In children, hay fever often is a factor in middle ear infection (otitis media).

Some people with allergic rhinitis also have asthma. Better control of allergic rhinitis has been shown to result in better asthma control in both adults and children. Emerging evidence shows that untreated allergic rhinitis can also increase the risk of developing asthma.

Nasal polyps

Nasal polyps are swellings that grow in the lining inside your nose or sinuses, the small cavities above and behind your nose.

They’re caused by inflammation of the membranes of the nose and sometimes develop as a result of rhinitis.

Nasal polyps are shaped like teardrops when they’re growing and look like a grape on a stem when fully grown.

They vary in size and can be yellow, grey or pink. They can grow on their own or in clusters, and usually affect both nostrils.

If nasal polyps grow large enough, or in clusters, they can interfere with your breathing, reduce your sense of smell and block your sinuses, which can lead to sinusitis.

Small nasal polyps can be shrunk using steroid nasal sprays so they don’t cause an obstruction in your nose. Large polyps may need to be surgically removed.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is a common complication of allergic rhinitis. It’s where the sinuses become inflamed or infected.

The sinuses naturally produce mucus, which usually drains into your nose through small channels.

However, if the drainage channels are inflamed or blocked – for example, because of allergic rhinitis or nasal polyps – the mucus can’t drain away and it may become infected.

Sinusitis is common and usually clears up on its own within 2 to 3 weeks. But medicines can help if it’s taking a long time to go away.

Common symptoms of sinusitis include:

- a blocked nose, making it difficult to breathe through your nose

- a runny nose

- mucus that drips from the back of your nose down your throat (post-nasal drip)

- a reduced sense of smell or taste

- a feeling of fullness, pressure or pain in the face

- snoring

- obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) – your airways become temporarily blocked while you’re asleep, which can disturb your sleep

Over-the-counter painkillers, such as paracetamol, ibuprofen or aspirin, can be used to help reduce any pain and discomfort in your face.

However, these medications aren’t suitable for everyone, so check the leaflet that comes with them before using them.

For example, children under the age of 16 shouldn’t take aspirin, and ibuprofen isn’t recommended for people with asthma or a history of stomach ulcers. Speak to your doctor or pharmacist if you’re unsure.

Antibiotics may also be recommended if your sinuses become infected with bacteria. If you have long-term (chronic) sinusitis, surgery may be needed to improve the drainage of your sinuses.

Sinusitis treatment

How you can treat sinusitis yourself

You can often treat mild sinusitis without seeing a doctor by:

- getting plenty of rest

- drinking plenty of fluids

- taking painkillers, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen – don’t give aspirin to children under 16

- holding a warm clean flannel over your face for a few minutes several times a day

- inhaling steam from a bowl of hot water – don’t let children do this because of the risk of scalding

- cleaning your nose with a salt water solution to ease congestion

How to clean your nose with a salt water solution

- Boil a pint of water, then leave it to cool

- Mix a teaspoon of salt and a teaspoon of bicarbonate of soda into the water

- Wash your hands

- Stand over a sink, cup the palm of one hand and pour a small amount of the solution into it

- Sniff the water into one nostril at a time

- Repeat these steps until your nose feels more comfortable

You don’t need to use all of the solution, but use a fresh one each day.

A pharmacist can advise you about medicines that can help, such as:

- decongestant nasal sprays, drops or tablets to unblock your nose

- salt water nasal sprays or solutions to rinse out the inside of your nose

You can buy nasal sprays without a prescription, but they shouldn’t be used for more than a week.

Some decongestant tablets also contain paracetamol or ibuprofen. If you’re taking painkillers as well as a decongestant, be careful not to take more than the recommended dose.

Treatment from a doctor

Your doctor may be able to recommend other medicines to help with your symptoms, such as:

- steroid nasal sprays or drops – to reduce the swelling in your sinuses

- antihistamines – if an allergy is causing your symptoms

- antibiotics – if a bacterial infection is causing your symptoms and you’re very unwell or at risk of complications (more rare)

You might need to take steroid nasal sprays or drops for a few months. They sometimes cause irritation, sore throats or nosebleeds.

Your doctor may refer you to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist if:

- these medicines don’t help with your sinusitis

- your sinusitis has lasted longer than 3 months (chronic sinusitis)

- you keep getting sinusitis

They may also recommend surgery in some cases.

Surgery for sinusitis

Surgery to treat chronic sinusitis is called functional endoscopic sinus surgery.

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery is carried out under general anaesthetic (where you’re asleep).

The surgeon can widen your sinuses by either:

- removing some of the blocked skin tissue

- inflating a tiny balloon in the blocked sinuses, then removing it

You should be able to have functional endoscopic sinus surgery within 18 weeks of your doctor appointment.

Middle ear infections

Middle ear infections (otitis media) can also develop as a complication of nasal problems, including allergic rhinitis.

These infections can occur if rhinitis causes a problem with the Eustachian tube, which connects the back of the nose and middle ear, at the back of the nose.

If this tube doesn’t function properly, fluid can build up in the middle ear behind the ear drum and can become infected.

There’s also the possibility of infection at the back of the nose spreading to the ear through the Eustachian tube.

The main symptoms of a middle ear infection usually start quickly and include:

- pain inside the ear

- a high temperature of 100.4 °F (38 °C) or above

- being sick

- a lack of energy

- difficulty hearing

- discharge running out of the ear

- feeling of pressure or fullness inside the ear

- itching and irritation in and around the ear

- scaly skin in and around the ear

Young children and babies with a middle ear infection may also:

- rub or pull their ear

- not react to some sounds

- be irritable or restless

- be off their food

- keep losing their balance

Most middle ear infections clear up within 3 days, although sometimes symptoms can last up to a week, but paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ibuprofen can be used to help relieve fever and pain. Antibiotics may also be prescribed if the symptoms persist or are particularly severe.

Middle ear infection treatment

If your child is older than 6 months of age and only has mild symptoms, the best treatment is to let the fluid go away on its own. You can give your child an over-the-counter pain reliever, such as acetaminophen, (one brand: Children’s Tylenol) if he or she is uncomfortable. A warm, moist cloth placed over the ear may also help.

Usually the fluid goes away in 2 to 3 months, and hearing returns to normal. Your doctor may want to check your child again at some point to see if fluid is still present. If it is, he or she may give your child antibiotics.

One treatment your doctor may suggest is a nasal balloon. A nasal balloon can help clear the fluid from the middle ear. You can easily use a nasal balloon at home. Your child will simply insert the balloon nozzle in one nostril while blocking the other nostril with a finger. Then, he or she will inflate the balloon with their nose.

If the fluid does not go away after a certain amount of time and treatment, your child may need ear tubes. These small tubes are inserted through the ear drum. They allow the doctor to suction out the fluid behind the ear. They also allow air to get into the middle ear, which helps prevent fluid build-up. Any hearing loss experienced by your child should be restored after the fluid is drained.

How to treat a middle ear infection yourself

To help relieve any pain and discomfort from a middle ear infection:

DO

- use painkillers such as paracetamol or ibuprofen (children under 16 shouldn’t take aspirin)

- place a warm or cold flannel on the ear

DON’T

- put anything inside your ear to remove earwax, such as cotton buds or your finger

- let water or shampoo get in your ear

- use decongestants or antihistamines – there’s no evidence they help with ear infections

FDA Warning

The. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advise against the use of ear candles. Ear candles can cause serious injuries and there is no evidence to support their effectiveness 12.

Treatment from a doctor

Your doctor may prescribe medicine for your ear infection, depending on what’s caused it.

Antibiotics aren’t usually offered because middle ear infections often clear up on their own, and antibiotics make little difference to symptoms, including pain.

Antibiotics might be prescribed if:

- an ear infection doesn’t start to get better after 3 days

- you or your child has any fluid coming out of their ear

- you or your child has an illness that means there’s a risk of complications, such as cystic fibrosis

They may also be prescribed if your child is less than 2 years old and has an infection in both ears.

Allergic rhinitis causes

Allergic rhinitis is caused when the body makes allergic antibodies (immunoglobulin E [IgE]) to harmless airborne indoor or outdoor allergens such as pollen, molds, house dust mite or pet dander (hair/skin) that are breathed in. If you have allergic rhinitis, your immune system mistakenly identifies a typically harmless substance as an intruder. In people sensitized to these allergens, exposure causes the release of histamine and chemical mediators, from cells in the nasal passages, eyes or airways. Some of these mediators, such as histamine, work quickly, causing sneezing, itching and runny nose. Others work more slowly causing an inflammatory reaction with symptoms such as blocked nose, reduced sense of smell and difficulty sleeping.

Seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever) is most often caused by pollen carried in the air during different times of the year in different parts of the country.

Allergic rhinitis can also be triggered by common indoor allergens such as the dried skin flakes, urine and saliva found on pet dander, mold, droppings from dust mites and cockroach particles. This is called perennial allergic rhinitis, as symptoms typically occur year-round.

In addition to allergen triggers, symptoms may also occur from irritants such as smoke and strong odors, or to changes in the temperature and humidity of the air. This happens because allergic rhinitis causes inflammation in the nasal lining, which increases sensitivity to inhalants.

Many people with allergic rhinitis are prone to allergic conjunctivitis (eye allergy). In addition, allergic rhinitis can make symptoms of asthma worse for people who suffer from both conditions.

Allergic rhinitis pathophysiology

In allergic rhinitis, numerous inflammatory cells, including mast cells, CD4-positive T cells (helper T cell), B cells (B lymphocytes), macrophages, and eosinophils, infiltrate the nasal lining upon exposure to an inciting allergen (most commonly airborne dust mite fecal particles, cockroach residues, animal dander, molds, and pollens). In allergic individuals, the T cells infiltrating the nasal mucosa are predominantly T helper 2 (Th2) in nature and release cytokines (e.g., interleukin [IL]-3, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) that promote immunoglobulin E (IgE) production by plasma cells. The allergic response is classified into early and late phase reactions. In the early phase, allergic rhinitis is an immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated response against inhaled allergens that cause inflammation driven by type 2 helper (Th2) cells 2. The initial response occurs within five to 15 minutes of exposure to an antigen, resulting in degranulation of host mast cells. This releases a variety of pre-formed and newly synthesized mediators, including histamine, which is one of the primary mediators of allergic rhinitis. Histamine induces sneezing via the trigeminal nerve and also plays a role in rhinorrhea by stimulating mucous glands. Other immune mediators such as leukotrienes and prostaglandins are also implicated as they act on blood vessels to cause nasal congestion. Four to six hours after the initial response, an influx of cytokines, such as interleukins (IL)-4 and IL-13 from mast cells occurs, signifying the development of the late phase response 13. These cytokines, in turn, facilitate the infiltration of eosinophils, T-lymphocytes, and basophils into the nasal mucosa and produce nasal edema with resultant congestion 14.

A non-IgE mediated hyperresponsiveness can develop due to eosinophilic infiltration and nasal mucosal obliteration. The nasal mucosa now becomes hyperreactive to normal stimuli (such as tobacco smoke, cold air) and causes symptoms of sneezing, rhinorrhea, and nasal pruritis 15.

There are data to suggest a genetic component to allergic rhinitis, but high-quality studies are generally lacking. Monozygotic twins show 45% to 60% concordance, and dizygotic twins have a concordance rate of approximately 25% in the development of allergic rhinitis. Specific regions on chromosomes 3 and 4 also correlate with allergic responses 16.

Figure 2. Development of allergic sensitization in allergic rhinitis

Footnotes: As shown in Panel A, sensitization involves allergen uptake by antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells) at a mucosal site, leading to activation of antigen-specific T cells, most likely at draining lymph nodes. Simultaneous activation of epithelial cells by nonantigenic pathways (e.g., proteases) can lead to the release of epithelial cytokines (thymic stromal lymphopoietin [TSLP], interleukin-25, and interleukin-33), which can polarize the sensitization process into a type 2 helper T (Th2) cell response. This polarization is directed toward the dendritic cells and probably involves the participation of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) and basophils, which release Th2-driving cytokines (interleukin-13 and interleukin-4). The result of this process is the generation of Th2 cells, which, in turn, drive B cells to become allergen-specific IgE-producing plasma cells. MHC denotes major histocompatibility complex. As shown in Panel B, allergen-specific IgE antibodies attach to high-affinity receptors on the surface of tissue-resident mast cells and circulating basophils. On reexposure, the allergen binds to IgE on the surface of those cells and cross-links IgE receptors, resulting in mast-cell and basophil activation and the release of neuroactive and vasoactive mediators such as histamine and the cysteinyl leukotrienes. These substances produce the typical symptoms of allergic rhinitis. In addition, local activation of Th2 lymphocytes by dendritic cells results in the release of chemokines and cytokines that orchestrate the influx of inflammatory cells (eosinophils, basophils, neutrophils, T cells, and B cells) to the mucosa, providing more allergen targets and up-regulating the end organs of the nose (nerves, vasculature, and glands). Th2 inflammation renders the nasal mucosa more sensitive to allergen but also to environmental irritants. In addition, exposure to allergen further stimulates production of IgE. As shown in Panel C, mediators released by mast cells and basophils can directly activate sensory-nerve endings, blood vessels, and glands through specific receptors. Histamine seems to have direct effects on blood vessels (leading to vascular permeability and plasma leakage) and sensory nerves, whereas leukotrienes are more likely to cause vasodilatation. Activation of sensory nerves leads to the generation of pruritus and to various central reflexes. These include a motor reflex leading to sneezing and parasympathetic reflexes that stimulate nasal-gland secretion and produce some vasodilatation. In addition, the sympathetic drive to the erectile venous sinusoids of the nose is suppressed, allowing for vascular engorgement and obstruction of the nasal passages. In the presence of allergic inflammation, these end-organ responses become up-regulated and more pronounced. Sensory-nerve hyperresponsiveness is a common pathophysiological feature of allergic rhinitis.

[Source 17 ]Oversensitive immune system

If you have allergic rhinitis, your immune system – your natural defence against infection and illness – will react to an allergen as if it were harmful.

If your immune system is oversensitive, it will react to allergens by producing antibodies to fight them off. Antibodies are special proteins in the blood that are usually produced to fight viruses and infections.

Allergic reactions don’t occur the first time you come into contact with an allergen. The immune system has to recognize and “memorize” it before producing antibodies to fight it. This process is known as sensitization.

After you develop sensitivity to an allergen, it will be detected by antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE) whenever it comes into contact with the inside of your nose and throat.

These antibodies cause cells to release a number of chemicals, including histamine, which can cause the inside layer of your nose (the mucous membrane) to become inflamed and produce excess mucus. This is what causes the typical symptoms of sneezing and a blocked or runny nose.

Common allergens

Allergic rhinitis is triggered by breathing in tiny particles of allergens. The most common airborne allergens that cause rhinitis are described below.

House dust mites

House dust mites are tiny insects that feed on the dead flakes of human skin. They can be found in mattresses, carpets, soft furniture, pillows and beds.

Rhinitis isn’t caused by the dust mites themselves, but by a chemical found in their excrement. Dust mites are present all year round, although their numbers tend to peak during the winter.

Pollen and spores

Tiny particles of pollen produced by trees and grasses can sometimes cause allergic rhinitis. Most trees pollinate from early to mid-spring, whereas grasses pollinate at the end of spring and beginning of summer.

Rhinitis can also be caused by spores produced by mold and fungi.

Animals

Many people are allergic to animals, such as cats and dogs. The allergic reaction isn’t caused by animal fur, but flakes of dead animal skin and their urine and saliva.

Dogs and cats are the most common culprits, although some people are affected by horses, cattle, rabbits and rodents, such as guinea pigs and hamsters.

However, being around dogs from an early age can help protect against allergies, and there’s some evidence to suggest that this might also be the case with cats.

Some people are affected by allergens found in their work environment, such as wood dust, flour dust or latex.

Risk factors for developing allergic rhinitis

The following can increase your risk of developing allergic rhinitis (hay fever):

- Having other allergies or asthma

- Having atopic dermatitis (eczema)

- Having a blood relative (such as a parent or sibling) with allergies or asthma

- Living or working in an environment that constantly exposes you to allergens — such as animal dander or dust mites

- Having a mother who smoked during your first year of life

Allergic rhinitis prevention

The best way to prevent allergic rhinitis is to avoid the allergen that causes it. But this isn’t always easy. Allergens, such as dust mites, aren’t always easy to spot and can breed in even the cleanest house. It can also be difficult to avoid coming into contact with pets, particularly if they belong to friends and family.

Below is some advice to help you avoid the most common allergens.

House dust mites

Dust mites are one of the biggest causes of allergies. They’re microscopic insects that breed in household dust.

To help limit the number of mites in your house, you should:

- consider buying an air-permeable occlusive mattress and bedding covers – this type of bedding acts as a barrier to dust mites and their droppings

- choose wood or hard vinyl floor coverings instead of carpet

- fit roller blinds that can be easily wiped clean

- regularly clean cushions, soft toys, curtains and upholstered furniture, either by washing or vacuuming them

- use synthetic pillows and acrylic duvets instead of woollen blankets or feather bedding

- use a vacuum cleaner fitted with a high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter – it can remove more dust than ordinary vacuum cleaners

- use a clean damp cloth to wipe surfaces – dry dusting can spread allergens further

Concentrate your efforts on controlling dust mites in the areas of your home where you spend most time, such as the bedroom and living room.

Pets

It isn’t pet fur that causes an allergic reaction, but exposure to flakes of their dead skin, saliva and dried urine.

If you can’t permanently remove a pet from the house, you may find the following tips useful:

- keep pets outside as much as possible or limit them to one room, preferably one without carpet

- don’t allow pets in bedrooms

- wash pets at least once a fortnight

- groom dogs regularly outside

- regularly wash bedding and soft furnishings your pet has been on

If you’re visiting a friend or relative with a pet, ask them not to dust or vacuum on the day you’re visiting because it will disturb allergens into the air.

Taking an antihistamine medicine one hour before you enter a house with a pet can help reduce your symptoms.

Pollen

Different plants and trees pollinate at different times of the year, so when you get allergic rhinitis will depend on what sort of pollen(s) you’re allergic to.

Most people are affected during the spring and summer months because this is when most trees and plants pollinate.

To avoid exposure to pollen, you may find the following tips useful:

- check weather reports for the pollen count and stay indoors when it’s high

- avoid line-drying clothes and bedding when the pollen count is high

- wear wraparound sunglasses to protect your eyes from pollen

- keep doors and windows shut during mid-morning and early evening, when there’s most pollen in the air

- shower, wash your hair and change your clothes after being outside

- avoid grassy areas, such as parks and fields, when possible

- if you have a lawn, consider asking someone else to cut the grass for you

Mold spores

Molds can grow on any decaying matter, both in and outside the house. The molds themselves aren’t allergens, but the spores they release are.

Spores are released when there’s a sudden rise in temperature in a moist environment, such as when central heating is turned on in a damp house or wet clothes are dried next to a fireplace.

To help prevent mold spores, you should:

- keep your home dry and well ventilated

- when showering or cooking, open windows but keep internal doors closed to prevent damp air spreading through the house, and use extractor fans

- avoid drying clothes indoors, storing clothes in damp cupboards and packing clothes too tightly in wardrobes

- deal with any damp and condensation in your home.

Allergic rhinitis diagnosis

Your doctor will often be able to diagnose allergic rhinitis from your symptoms and your personal and family medical history. Your doctor will ask you whether you’ve noticed any triggers that seem to cause a reaction, and whether it happens at a particular place or time. Your doctor may examine the inside of your nose to check for nasal polyps. Nasal polyps are fleshy swellings that grow from the lining of your nose or your sinuses, the small cavities inside your nose. They can be caused by the inflammation that occurs as a result of allergic rhinitis.

Allergic rhinitis is usually confirmed when medical treatment starts. If you respond well to antihistamines, it’s almost certain that your symptoms are caused by an allergy.

Allergy testing

If the exact cause of allergic rhinitis is uncertain, your doctor may refer you to a hospital allergy clinic for allergy testing.

The two main allergy tests are:

- Skin prick test – where the allergen is placed on your arm and the surface of the skin is pricked with a needle to introduce the allergen to your immune system; if you’re allergic to the substance, a small itchy spot (welt or bump) will appear. Allergy specialists usually are best equipped to perform allergy skin tests.

- Blood test also called the radioallergosorbent test (RAST) – to check for the immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody in your blood; your immune system produces this antibody in response to a suspected allergen.

Commercial allergy testing kits aren’t recommended because the testing is often of a lower standard than that provided by the allergy specialist or an accredited private clinic.

It’s also important that the test results are interpreted by a qualified healthcare professional with detailed knowledge of your symptoms and medical history.

Further tests

In some cases further hospital tests may be needed to check for complications, such as nasal polyps or sinusitis.

For example, you may need:

- a nasal endoscopy – where a thin tube with a light source and video camera at one end (endoscope) is inserted up your nose so your doctor can see inside your nose

- a nasal inspiratory flow test – where a small device is placed over your mouth and nose to measure the air flow when you inhale through your nose

- a computerized tomography (CT) scan – a scan that uses X-rays and a computer to create detailed images of the inside of the body.

Allergic rhinitis treatment

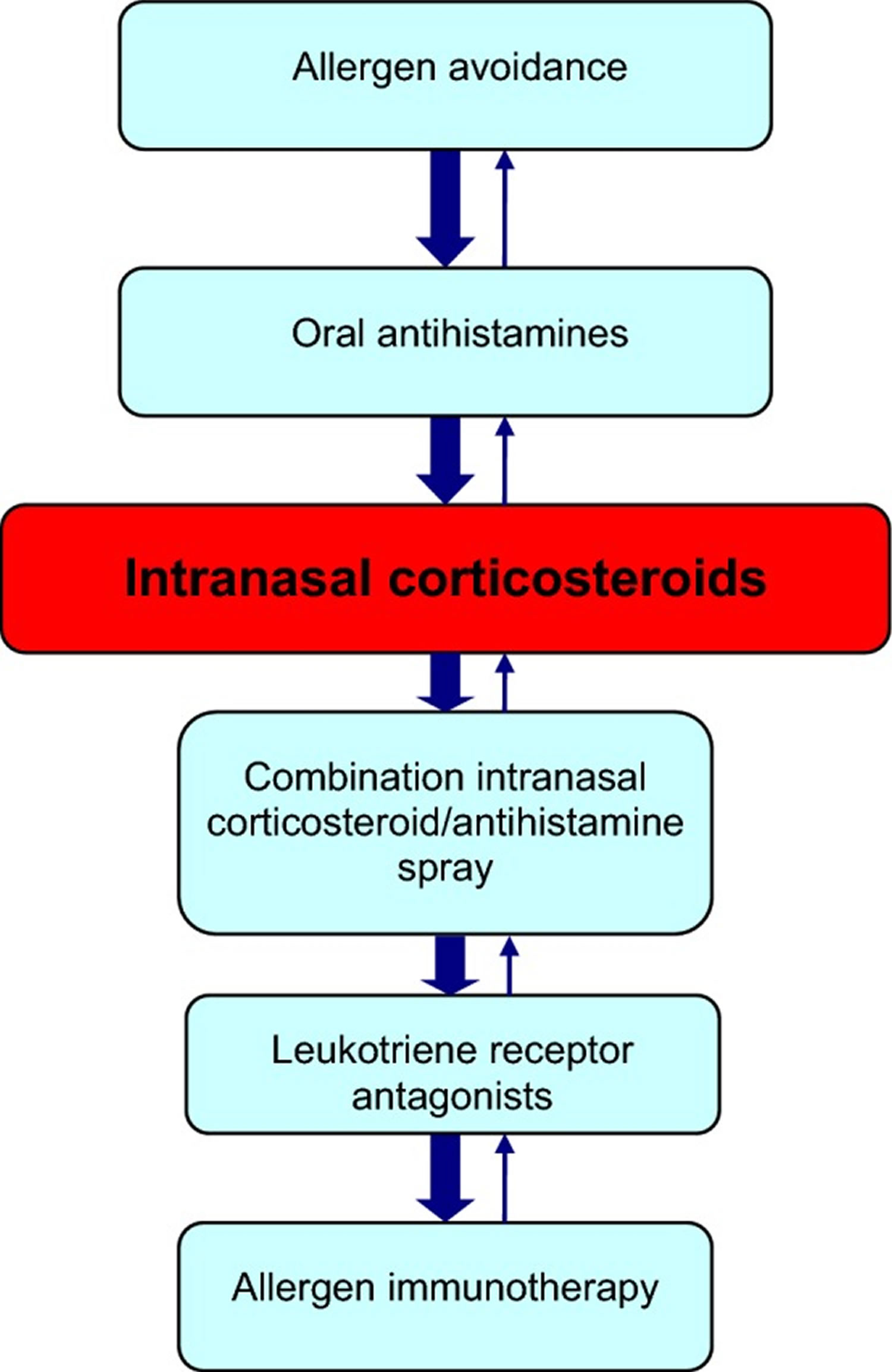

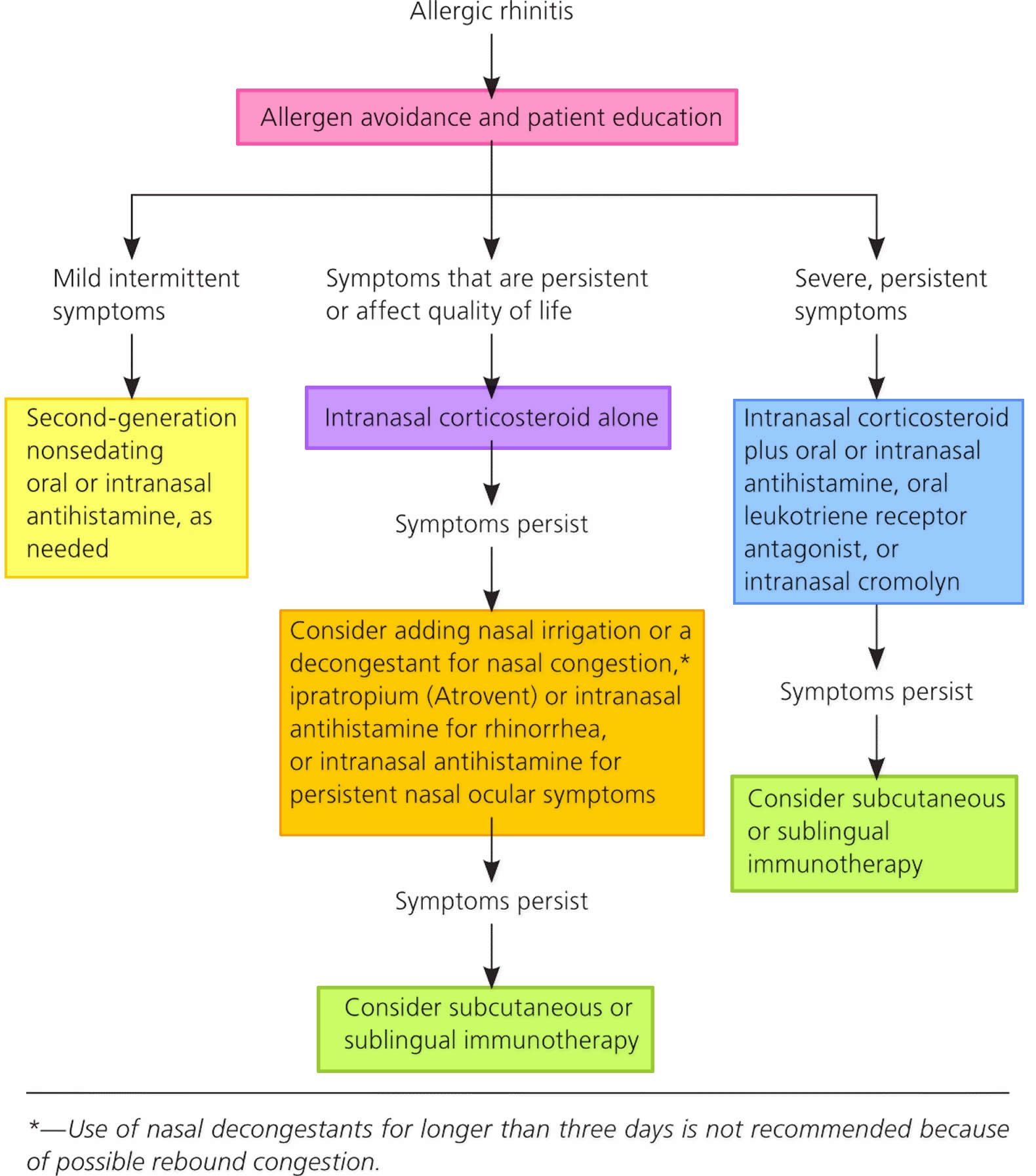

Treatment for allergic rhinitis depends on how severe your symptoms are and how much they’re affecting your everyday activities. In most cases treatment aims to relieve symptoms such as sneezing and a blocked or runny nose. Therapeutic options available to relieve your symptoms include avoidance measures, nasal saline irrigation, oral antihistamines, intranasal corticosteroids, combination intranasal corticosteroid/antihistamine sprays; leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs), and allergen immunotherapy 6. Other therapies that may be useful in select patients include decongestants and oral corticosteroids.

If you have mild allergic rhinitis, you can often treat the symptoms yourself with over-the-counter medications such as non-sedating antihistamines which may be enough to relieve your symptoms.

You should visit your doctor if your symptoms are more severe and affecting your quality of life, or if self-help measures haven’t been effective.

In addition, allergic rhinitis and asthma appear to represent a combined airway inflammatory disease and, therefore, treatment of asthma is also an important consideration in patients with allergic rhinitis.

Figure 3. Allergic rhinitis treatment algorithm

[Source 6, 18 ]Table 1. Pharmacotherapy and Immunotherapy for Allergic Rhinitis

| Type of Symptoms | Recommended Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| Episodic symptoms | Oral or nasal H1-antihistamine, with oral or nasal decongestant if needed |

| Mild symptoms, seasonal or perennial | Intranasal glucocorticoid,† oral or nasal H1-antihistamine, or leukotriene- receptor antagonist (e.g., montelukast) |

| Moderate-to-severe symptoms‡ | Intranasal glucocorticoid,§ intranasal glucocorticoid plus nasal H1-antihistamine, ¶ or allergen immunotherapy administered subcutaneously or sublingually (the latter for grass or ragweed only)∥ |

Footnotes:

*Common or severe adverse effects are as follows: for oral antihistamines, sedation and dry mouth (predominantly with older agents); for nasal antihistamines, bitter taste, sedation, and nasal irritation; for oral decongestants, palpitations, insomnia, jitteriness, and dry mouth; for nasal decongestants, rebound nasal congestion and the potential for severe central nervous system and cardiac side effects in small children; for leukotriene-receptor antagonists, bad dreams and irritability; for nasal glucocorticoids, nasal irritation, nosebleeds, and sore throat; for sublingual immunotherapy, oral pruritus and edema, systemic allergic reactions (epinephrine auto-injectors are advised per the package insert), and eosinophilic esophagitis; and for subcutaneous immunotherapy, local and systemic allergic reactions (therapy should be administered only in a setting where emergency treatment is available).

†Intranasal glucocorticoids are more efficacious than oral antihistamines or montelukast, but the difference may not be as evident if the symptoms are mild.

‡Moderate-to-severe allergic rhinitis is defined by the presence of one or more of the following: sleep disturbance, im- pairment of usual activities or exercise, impairment of school or work performance, or troublesome symptoms.

§An oral H1-antihistamine plus montelukast is an alternative for patients for whom nasal glucocorticoids are associated with unacceptable side effects or for those who do not wish to use them; the efficacy of this combination is not unequivo- cally inferior to that of an intranasal glucocorticoid.

¶This combination is more efficacious than an intranasal glucocorticoid alone.

∥Allergen immunotherapy should be used in patients who do not have adequate control with pharmacotherapy or who prefer allergen immunotherapy.

[Source 17 ]Allergic rhinitis home remedies

It’s possible to treat the symptoms of mild allergic rhinitis with over-the-counter medications, such as long-acting, non-sedating antihistamines.

If possible, try to reduce exposure to the allergen that triggers the condition. See preventing allergic rhinitis for more information and advice about this.

Cleaning your nasal passages

Regularly cleaning your nasal passages with a salt water solution – known as nasal douching or irrigation – can also help by keeping your nose free of irritants.

You can do this either by using a homemade solution or a solution made with sachets of ingredients bought from a pharmacy. Or you can buy a saline spray at a pharmacy.

Small syringes or pots (Neti pot) that often look like small horns or teapots are also available to help flush the solution around the inside of your nose.

Nasal wash

- To make the solution at home, mix half a teaspoon of salt and half a teaspoon of bicarbonate of soda (baking powder) into a pint (568ml) of boiled water that’s been left to cool to around body temperature – do not attempt to rinse your nose while the water is still hot.

To rinse your nose:

- stand over a sink, cup the palm of one hand and pour a small amount of the solution into it

- sniff the water into one nostril at a time

- repeat this until your nose feels comfortable – you may not need to use all of the solution

While you do this, some solution may pass into your throat through the back of your nose. The solution is harmless if swallowed, but try to spit out as much of it as possible.

Nasal irrigation can be carried out as often as necessary, but a fresh solution should be made each time.

Allergic rhinitis medication

Medication won’t cure your allergy, but it can be used to treat the common symptoms.

If your symptoms are caused by seasonal allergens, such as pollen, you should be able to stop taking your medication after the risk of exposure has passed.

Visit your doctor if your symptoms don’t respond to medication after two weeks.

Intranasal corticosteroids

If you have frequent or persistent symptoms and you have a nasal blockage or nasal polyps, your doctor may recommend a nasal spray or drops containing corticosteroids. Intranasal corticosteroids are also first-line therapeutic options for patients with mild persistent or moderate/severe symptoms and they can be used alone or in combination with oral antihistamines. For many people intranasal corticosteroids are the most effective allergic rhinitis (hay fever) medications, and they’re often the first type of medication prescribed. Studies and meta-analyses have shown that intranasal corticosteroids are superior to antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists in controlling the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, including nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea 19. Intranasal corticosteroids have also been shown to improve ocular symptoms and reduce lower airway symptoms in patients with concurrent asthma and allergic rhinitis 20.

Nasal corticosteroid sprays (e.g., Budesonide [Rhinocort], Mometasone furoate [Nasonex]) are the most effective treatment. Many brands are available. You can buy some brands without a prescription. For other brands, you need a prescription.

Nasal corticosteroids are a safe, long-term treatment for most people. Side effects can include an unpleasant smell or taste and nose irritation and stinging. These side effects can usually be prevented by aiming the spray slightly away from the nasal septum 5. Steroid side effects are rare. Evidence suggests that intranasal beclomethasone and triamcinolone, but not other intranasal corticosteroids, may slow growth in children compared to placebo. However, long-term studies examining the impact of usual doses of intranasal beclomethasone on growth are lacking 21.

- Nasal corticosteroid sprays work best when you use them every day.

- It may take 2 or more weeks of steady use for your symptoms to improve.

- Nasal corticosteroid sprays are safe for children and adults.

Corticosteroids help reduce inflammation and swelling. They take longer to work than antihistamines, but their effects last longer. Side effects from inhaled corticosteroids are rare, but can include nasal dryness, irritation and nosebleeds.

Intranasal corticosteroids are cheaper than antihistamines and provide better relief of nasal symptoms, however the two can be used together for optimal symptom control.

Combination intranasal corticosteroid and antihistamine nasal spray

If intranasal corticosteroids are not effective, a combination corticosteroid/antihistamine spray can be tried. Combination fluticasone propionate/azelastine hydrochloride (Dymista) is now available. This combination spray has been shown to be more effective than the individual components with a safety profile similar to intranasal corticosteroids 22.

Oral corticosteroids

Corticosteroid pills such as prednisone sometimes are used to relieve severe allergy symptoms. Because the long-term use of corticosteroids can cause serious side effects such as cataracts, osteoporosis and muscle weakness, they’re usually prescribed for only short periods of time.

If you have a particularly severe bout of symptoms and need rapid relief, your doctor may prescribe a short course of oral corticosteroid tablets such as prednisone lasting 5 to 10 days.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines (e.g., Cetirizine hydrochloride [Zyrtec], Fexofenadine hydrochloride [Telfast]) relieve symptoms of allergic rhinitis by blocking the action of a chemical called histamine, which the body releases when it thinks it’s under attack from an allergen.

Antihistamines are often used when symptoms do not occur very often or do not last very long.

- Antihistamines can be bought as a pill, capsule, or liquid without a prescription.

- Over-the-counter pills include loratadine (Claritin, Alavert), cetirizine (Zyrtec Allergy) and fexofenadine (Allegra Allergy).

- The prescription antihistamine nasal sprays azelastine (Astelin, Astepro) and olopatadine (Patanase) can relieve nasal symptoms.

- Antihistamine eyedrops such as ketotifen fumarate (Alaway) help relieve eye itchiness and eye irritation caused by hay fever.

- Older antihistamines can cause sleepiness. They may affect a child’s ability to learn and make it unsafe for adults to drive or use machinery.

- Newer antihistamines cause little or no sleepiness or learning problems.

- Antihistamine nasal sprays work well for treating allergic rhinitis. They are only available with a prescription.

You can buy antihistamine tablets over the counter from your pharmacist without a prescription, but antihistamine nasal sprays are only available with a prescription.

Antihistamines can sometimes cause drowsiness. If you’re taking them for the first time, see how you react to them before driving or operating heavy machinery. In particular, antihistamines can cause drowsiness if you drink alcohol while taking them.

Intranasal antihistamines

Histamine is the most studied mediator in early allergic response. Histamine causes smooth muscle constriction, mucus secretion, vascular permeability, and sensory nerve stimulation, resulting in the symptoms of allergic rhinitis.

Compared with oral antihistamines, intranasal antihistamines have the advantage of delivering a higher concentration of medication to a targeted area, resulting in fewer adverse effects and an onset of action within 15 minutes 23. Intranasal antihistamines FDA-approved for the treatment of allergic rhinitis are azelastine (Astelin; for patients five years and older) and olopatadine (Patanol; for patients six years and older). They have been shown to be similar or superior to oral antihistamines in treating symptoms of conjunctivitis and rhinitis, and may improve congestion 24. Adverse effects include a bitter aftertaste, headache, nasal irritation, epistaxis, and sedation. Although intranasal antihistamines are an option if symptoms do not improve with nonsedating oral antihistamines, their use as first- or second-line therapy is limited by adverse effects, twice daily dosing, cost, and decreased effectiveness compared with intranasal corticosteroids 24.

Oral antihistamines

First-generation antihistamines, including brompheniramine, chlorpheniramine, clemastine, and diphenhydramine (Benadryl), may cause sedation, fatigue, and impaired mental status. These adverse effects occur because the older antihistamines are more lipid soluble and more readily cross the blood-brain barrier than second-generation antihistamines. The use of first-generation sedating antihistamines has been associated with poor school performance, impaired driving, and increased automobile collisions and work injuries 25.

Compared with first-generation antihistamines, second-generation drugs have a better adverse effect profile and cause less sedation, with the exception of cetirizine (Zyrtec) 26. Second-generation nonsedating oral antihistamines include loratadine (Claritin), desloratadine (Clarinex), levocetirizine (Xyzal), and fexofenadine (Allegra). Second-generation antihistamines have more complex chemical structures that decrease their movement across the blood-brain barrier, reducing central nervous system adverse effects such as sedation. Although cetirizine is generally classified as a second-generation antihistamine and a more potent histamine antagonist, it does not have the benefit of decreased sedation.

In general, oral antihistamines have been shown to effectively relieve the histamine-mediated symptoms associated with allergic rhinitis (e.g., sneezing, pruritus, rhinorrhea), but they are less effective than intranasal corticosteroids at treating nasal congestion and ocular symptoms. Because their onset of action is typically within 15 to 30 minutes and they are considered safe for children older than two years, second-generation antihistamines are useful for many patients with mild symptoms requiring as-needed treatment 27.

Decongestants

Oral and intranasal decongestants (e.g., Phenylephrine hydrochloride [Sudafed], oxymetazoline [Afrin] and pseudoephedrine) are medicines that help dry up a runny or stuffy nose associated with allergic rhinitis by acting on adrenergic receptors, which causes vasoconstriction in the nasal mucosa, decreasing inflammation 28, 23. Decongestants come as pills, liquids, capsules, or nasal sprays. You can buy them over-the-counter (OTC), without a prescription. Over-the-counter oral decongestants include pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, Afrinol, others). Nasal sprays include phenylephrine hydrochloride (Neo-Synephrine) and oxymetazoline (Afrin).

Oral decongestants can cause a number of side effects, including increased blood pressure, elevated intraocular pressure, insomnia, irritability, tremor, urinary retention, dizziness, tachycardia, and headache; therefore, these medications should be used with caution in patients with underlying cardiovascular conditions, glaucoma, or hyperthyroidism 23. Common adverse effects of intranasal decongestants are sneezing and nasal dryness.

- Decongestants may be considered for short-term use in patients without improvement in congestion with intranasal corticosteroids 29.

- You can use decongestants along with antihistamine pills or liquids.

- DO NOT use nasal spray decongestants for more than 3 days in a row because it can actually worsen symptoms when used continuously (rebound congestion or rhinitis medicamentosa) 29.

- The abuse potential for pseudoephedrine should be weighed against its benefits.

- Talk to your child’s health care provider before giving decongestants to your child.

Eye drops

Eye drops containing anti-histamine or steroids may be used to control symptoms such as itchy or watery eyes e.g., Ketotifen fumarate (Zaditen), Hydrocortisone acetate (Hycor).

Leukotriene modifier (leukotriene receptor antagonists)

Montelukast and zafirlukast is a prescription tablet taken to block the action of leukotrienes — immune system chemicals that cause allergy symptoms such as excess mucus production, however, they do not appear to be as effective as intranasal corticosteroids 30. They’re especially effective in treating allergy-induced asthma. Leukotriene receptor antagonist is often used when nasal sprays can’t be tolerated or for mild asthma.

Montelukast can cause headaches. In rare cases, it has been linked to psychological reactions such as agitation, aggression, hallucinations, depression and suicidal thinking. Seek medical advice right away for any unusual psychological reaction.

Cromolyn sodium

Intranasal sodium cromoglycate (Cromolyn) is available as an over-the-counter nasal spray that must be used several times a day. It’s also available in eye-drop form with a prescription. It helps relieve hay fever symptoms by preventing the release of histamine 1. Intranasal sodium cromoglycate (Cromolyn) has been shown to reduce sneezing, rhinorrhea and nasal itching and is, therefore, a reasonable therapeutic option for some patients. Most effective when you start using it before you have symptoms. Although safe for general use, it is not considered first-line therapy for allergic rhinitis because it is less effective than antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids and is given three or four times daily 31.

Nasal ipratropium

Available in a prescription nasal spray, intranasal ipratropium (Atrovent) helps relieve severe runny nose (severe rhinorrhea) by preventing the glands in your nose from producing excess fluid. The recommended administration is two to three times daily 1. Intranasal ipratropium (Atrovent) is not effective for treating congestion, sneezing or postnasal drip than intranasal corticosteroids 32.

Mild side effects include nasal dryness, nosebleeds, sore throat and headache. Rarely, it can cause more-severe side effects, such as blurred vision, dizziness and difficult urination. The drug is not recommended for people with glaucoma or men with an enlarged prostate.

Add-on treatments

If allergic rhinitis doesn’t respond to treatment, your doctor may choose to add to your original treatment.

Your doctor may suggest:

- increasing the dose of your corticosteroid nasal spray

- using a short-term course of a decongestant nasal spray to take with your other medication

- combining antihistamine tablets with corticosteroid nasal sprays, and possibly decongestants

- using a nasal spray that contains a medicine called ipratropium, which will help reduce excessive nasal discharge

- using a leukotriene receptor antagonist medication – medication that blocks the effects of chemicals called leukotrienes, which are released during an allergic reaction

If you don’t respond to the add-on treatments, you may be referred to a specialist for further assessment and treatment.

Allergen immunotherapy

Immunotherapy also known as hyposensitisation, desensitisation or allergy shot, is another type of treatment used for some allergies. Allergen immunotherapy is only suitable for people with certain types of allergies, such as hay fever, and is usually only considered if your symptoms are severe. Immunotherapy involves gradually introducing more and more of the allergen into your body to make your immune system less sensitive to it. The allergen is often injected under the skin of your upper arm. Injections are given at weekly intervals, with a slightly increased dose each time.

Immunotherapy can also be carried out using tablets that contain an allergen, such as grass pollen, which are placed under your tongue.

When a dose is reached that’s effective in reducing your allergic reaction (the maintenance dose), you’ll need to continue with the injections or tablets for up to three years.

Immunotherapy should only be carried out under the close supervision of a specially trained doctor as there’s a risk it may cause a serious allergic reaction.

The appropriate use, timing of initiation, and duration of immunotherapy remain uncertain. The general recommendation in the United States has been to start immunotherapy only for patients in whom symptom control is not adequate with pharmacotherapy or those who prefer immunotherapy to pharmacotherapy 33. However, the Preventive Allergy Treatment Study, in which children with allergic rhinitis but without asthma were randomly assigned to subcutaneous immunotherapy or a pharmacotherapy control, showed that fewer children had new allergies or asthma after 3 years of immunotherapy, and this preventive effect persisted 7 years after therapy was discontinued 34. A similar large trial using sublingual immunotherapy is ongoing 35.

With subcutaneous immunotherapy, the standard practice in the United States is to administer multiple allergens (on average, eight allergens simultaneously in a single injection or multiple injections) because most patients are sensitized and symptomatic on exposure to multiple allergens. It is not known whether multi-allergen therapy results in better outcomes than single-allergen therapy. Although some older studies suggest a benefit of multi-allergen immunotherapy, most trials showing the efficacy of immunotherapy involve a single allergen.

The role of allergen avoidance in the prevention of allergic rhinitis is controversial. Avoidance of seasonal inhalant allergens is universally recommended on the basis of empirical evidence, but the efficacy of strategies to avoid exposure to perennial allergens, including dust mites, pest allergens (cockroach and mouse), and molds, has been questioned. For abatement strategies to be successful, allergens need to be reduced to very low levels, which are difficult to achieve. Abatement usually requires a multifaceted and continuous approach, raising feasibility problems. Multifaceted programs have been effective in the management of asthma but have not been studied in allergic rhinitis.

Allergic rhinitis guidelines

Guidelines for the treatment of allergic rhinitis are available from the international community (Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma [ARIA] guidelines) and jointly from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology in the United States 36. Differences between the two sets of guidelines exist. For example, the ARIA guidelines 36 do not recommend oral decongestants, even when combined with antihistamines, except as rescue medications, and they recommend nasal antihistamines only for seasonal use. Whereas the ARIA guidelines do not specifically endorse combinations of medications, the U.S. guidelines recommend a stepped-care approach that can include more than one medication. The U.S. guidelines were written before Food and Drug Administration approval of sublingual immunotherapy, and therefore this treatment is not discussed. The recommendations in this article are largely concordant with both sets of guidelines.

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) Recommendations

I. Prevention of allergy

Recommendation 1:

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) suggest exclusive breastfeeding for at least first three months for all infants irrespective of their family history of atopy (conditional recommendation | low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on the prevention of allergy and asthma, and a relatively low value on challenges or burden of breastfeeding in certain situations.

Remarks

The evidence, that exclusive breastfeeding for at least the first three months reduces the risk of allergy or asthma, is not convincing and, therefore, the recommendation to exclusively breastfeed is conditional. This recommendation applies to situations in which other reasons do not suggest harm from breastfeeding (e.g. classic galactosemia, active untreated tuberculosis or human immunodeficiency virus infection in mother, antimetabolites or chemotherapeutic agents or radioactive isotopes being used in the mother for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes until they clear from the milk, and bacterial or viral infection of a breast).

Recommendation 2:

For pregnant or breastfeeding women, we suggest no antigen avoidance diet to prevent development of allergy in children (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on adequate nourishment of mothers and children, and a relatively low value on very uncertain effects on the prevention of allergy and asthma in this setting.

Recommendation 3:

In children and pregnant women, we recommend total avoidance of environmental tobacco smoke (i.e. passive smoking) (strong recommendation | very low quality evidence).

Remarks

Smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke are common health problems around the world causing a substantial burden of disease for children and adults. While it is very rare to make a strong recommendation based on low or very low quality evidence, the ARIA guideline panel felt that in the absence of important adverse effects associated with smoking cessation or reducing the exposure to second-hand smoke, the balance between the desirable and undesirable effects is clear.

Recommendation 4:

In infants and preschool children, we suggest multifaceted interventions to reduce early life exposure to house dust mite (conditional recommendation | low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively low value on the burden and cost of using multiple preventive measures (e.g. encasings to parental and child’s bed, washing bedding and soft toys at temperature exceeding 55°C [131°F], use of acaricide, smooth flooring without carpets, etc.), and relatively high value on an uncertain small reduction of the risk of developing wheeze or asthma. For some children at lower risk of developing asthma and in certain circumstances an alternative choice will be equally reasonable.

Remarks

Children at high risk of developing asthma are those with at least one parent or sibling with asthma or other allergic disease.

Recommendation 5:

In infants and preschool children, we suggest no special avoidance of exposure to pets at home (conditional recommendation | low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on possible psychosocial downsides of not having a pet, and relatively low value on potential reduction in the uncertain risk of developing allergy and/or asthma.

Remarks

Clinicians and patients may reasonably choose an alternative action, considering circumstances that include other sensitized family members.

Recommendation 6:

For individuals exposed to occupational agents, we recommend specific prevention measures eliminating or reducing occupational allergen exposure (strong recommendation | low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on reducing the risk of sensitization to occupational allergens and developing occupational rhinitis and/or asthma with the subsequent adverse consequences, and a relatively low value on the feasibility and cost of specific strategies aimed at reducing occupational allergen exposure.

Remarks

Total allergen avoidance, if possible, seems to be the most effective primary prevention measure.

II. Treatment of allergic rhinitis

Reducing allergen exposure

Recommendation 7:

In patients with allergic rhinitis and/or asthma sensitive to house dust mite allergens, we recommend that clinicians do not administer and patients do not use currently available single chemical or physical preventive methods aimed at reducing exposure to house dust mites (strong recommendation | low quality evidence) or their combination (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence), unless this is done in the context of formal clinical research.

We suggest multifaceted environmental control programmes be used in inner-city homes to improve symptoms of asthma in children (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

The recommendation to use multifaceted environmental control programmes in inner-city homes places a relatively high value on possible reduction in the symptoms of asthma in children, and relatively low value on the cost of such programmes.

Recommendation 8:

In patients allergic to indoor moulds, Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) suggest avoiding exposure to these allergens at home (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on possible reduction in the symptoms of rhinitis and asthma, and a relatively low value on the burden and cost of interventions aimed at reducing exposure to household moulds.

Recommendation 9:

In patients with allergic rhinitis due to animal dander, we recommend avoiding exposure to these allergens at home (strong recommendation | very low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on potential reduction of symptoms of allergic rhinitis, and a relatively low value on psychosocial downsides of not having a pet or the inconvenience and cost of environmental control measures.

Remarks

Based on biological rationale, there is little doubt that total avoidance of animal allergens at home, and probably also marked reduction in their concentration, can improve symptoms, despite paucity of published data to substantiate this statement.

Recommendation 10:

In patients with occupational asthma, we recommend immediate and total cessation of exposure to occupational allergen (strong recommendation | very low quality evidence). When total cessation of exposure is not possible, we suggest specific strategies aimed at minimizing occupational allergen exposure (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

The recommendation to immediately and totally cease the exposure to occupational allergen places a relatively high value on reducing the symptoms of asthma and deterioration of lung function, and a relatively low value on the potential socioeconomic downsides (e.g. unemployment).

Pharmacological treatment of allergic rhinitis

Recommendation 11:

In patients with allergic rhinitis, we recommend new generation oral H1-antihistamines that do not cause sedation and do not interact with cytochrome P450 (strong recommendation | low quality evidence). In patients with allergic rhinitis, we suggest new generation oral H1-antihistamines that cause some sedation and/or interact with cytochrome P450 (conditional recommendation | low quality evidence).

The recommendation to use new generation oral H1-antihistamines that cause some sedation and/or interact with cytochrome P450 places a relatively high value on a reduction of symptoms of allergic rhinitis, and a relatively low value on side effects of these medications.

Remarks

Astemizole and terfenadine were removed from the market due to cardiotoxic side effects.

See recommendation 12 referring to the comparison of new generation versus old generation agents for the choice of one over the other.

Recommendation 12:

In patients with allergic rhinitis, we recommend new generation over old generation oral H1-antihistamines (strong recommendation | low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on the reduction of adverse effects, and a relatively low value on an uncertain comparative efficacy of new versus old generation oral H1-antihistamines.

Recommendation 13:

In infants with atopic dermatitis and/or family history of allergy or asthma (at high risk of developing asthma), we suggest clinicians do not administer and parents do not use oral H1-antihistamines for the prevention of wheezing or asthma (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on avoiding side effects of oral H1-antihistamines in infants, and a lower value on the very uncertain reduction in the risk of developing asthma or wheezing.

Remarks

The recommendation not to use oral H1-antihistamines in these infants refers only to prevention of asthma or wheezing. The guideline panel did not consider other conditions in which these medications may be commonly used (e.g. urticaria).

Recommendation 14:

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) suggest intranasal H1-antihistamines in adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation| low quality evidence) and in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence). In adults and children with perennial/persistent allergic rhinitis, we suggest that clinicians do not administer and patients do not use intranasal H1-antihistamines until more data on their relative efficacy and safety is available (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

The recommendation to use intranasal H1-antihistamines in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis places a relatively high value on reduction of symptoms, and a relatively low value on the risk of rare or mild side effects. The recommendation not to use intranasal H1-antihistamines in patients with perennial/persistent allergic rhinitis places a relatively high value on their uncertain efficacy and possible side effects, and a relatively low value on possible small reduction in symptoms.

Recommendation 15:

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) suggest new generation oral H1-antihistamines rather than intranasal H1-antihistamines in adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | moderate quality evidence) and in adults with perennial/persistent allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence). In children with intermittent or persistent allergic rhinitis we also suggest new generation oral H1-antihistamines rather than intranasal H1-antihistamines (conditional recommendation | very low quality evidence).

These recommendations place a relatively high value on probable higher patient preference for oral versus intranasal route of administration as well as avoiding bitter taste of some intranasal H1-antihistamines, and relatively low value on increased somnolence with some new generation oral H1-antihistamines. In many patients with different values and preferences or those who experience adverse effects of new generation oral H1-antihistamines an alternative choice may be equally reasonable.

Recommendation 16:

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) suggest oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in adults and children with seasonal allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | high quality evidence) and in preschool children with perennial allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | low quality evidence). In adults with perennial allergic rhinitis we suggest that clinicians do not administer and patients do not use oral leukotriene receptor antagonists (conditional recommendation | high quality evidence).

The recommendation to use oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in adults and children with seasonal allergic rhinitis and in preschool children with perennial allergic rhinitis places a relatively high value on their safety and tolerability, and relatively low value on their limited efficacy and high cost.

The recommendation not to use oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in adults with perennial allergic rhinitis places a relatively high value on their very limited efficacy and high cost, and relatively low value on potential small benefit in few patients.

Remarks

Evidence is available only for montelukast. This recommendation refers to the treatment of rhinitis, not to the treatment of asthma in patients with concomitant allergic rhinitis (see recommendation 45).

Recommendation 17:

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) suggest oral H1-antihistamines over oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | moderate quality evidence) and in preschool children with perennial allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | low quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on avoiding resource expenditure.

Recommendation 18:

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) recommend intranasal glucocorticosteroids for treatment of allergic rhinitis in adults (strong recommendation | high quality evidence) and suggest intranasal glucocorticosteroids in children with allergic rhinitis (conditional recommendation | moderate quality evidence).

This recommendation places a relatively high value on the efficacy of intranasal glucocorticosteroids, and a relatively low value on avoiding their possible adverse effects.

Recommendation 19: