Amebiasis

Amebiasis also known as amebic dysentery is a gastrointestinal illness caused by a pseudopod-forming, nonflagellated protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) 1, 2, 3, 4. Amebiasis is endemic in the developing countries of India, Africa, Mexico, and Central and South America 5, 6. Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) is spread through contaminated food or water, or by person-to-person contact via fecal-oral transmission 7. Anyone can get amebiasis. Amebiasis is more common in people living in or traveling to tropical areas with poor sanitary conditions 8, 9. Amebiasis can also affect men who have sex with men 10, 11, 12, 13. Amebiasis in the United States is seen mostly in returning travelers or immigrants from endemic countries 14, 5, 6,. Most people who are infected don’t get sick. Symptoms are often mild for those who do get ill and can include diarrhea and stomach pain.

The estimations of the worldwide burden of amoebiasis by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that approximately 500 million people were infected with Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) parasite and 10% of these individuals had invasive amoebiasis 15. In the largest global study of childhood diarrheal illness conducted to date, Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) was shown to be a top cause of severe diarrhea among infants and children living in Africa and Asia, and was the leading cause of mortality in the 12 to 24 month age group 16. Invasive intestinal amebiasis (amebic colitis) is a leading cause of diarrhea and is estimated to kill more than 55,000 people each year 17. Amebic colitis (invasive intestinal amebiasis) is a leading cause of severe diarrhea worldwide and is listed among the top 15 causes of diarrhea in the first 2 years of life in children living in the developing world, where diarrhea remains the third leading cause of death, accounting for 9% of all deaths in children under the age of 5 years 17, 18, 19. Fulminant amebic colitis is an uncommon but life threatening complication of amebiasis but is associated with high mortality, and on average more than 50% with severe colitis die 20.

Not everyone who has an amebiasis infection gets sick. You might not have any amebiasis symptoms, especially when you’re first infected. Approximately 80% of patients with amebiasis will develop symptoms within 2 to 4 weeks, including fever and right upper quadrant abdominal pain with 10% to 35% of patients experiencing associated gastrointestinal symptoms 4. Amebiasis symptoms include:

- Cramping (abdominal pain).

- Diarrhea (sometimes with rectal bleeding).

- Fever.

- Loose stools (amebiasis stool color may not change, but stools may be watery).

- Nausea.

E. histolytica can live in your intestines for a long time, even if you don’t develop symptoms. If you’ve traveled to an area with unsanitary conditions, ask your doctor if you should undergo testing.

If your doctor suspects you having intestinal amebiasis, your doctor will ask for a sample of your poop. You may be asked for several poop samples from different days. This is because Entamoeba histolytica parasite is not always found in every sample. Diagnosing amebiasis can be very difficult. Other parasites and cells can look very similar to Entamoeba histolytica parasite under a microscope. If you’ve been told that you have an Entamoeba histolytica infection but you’re feeling fine, you might be infected with a different parasite, Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar). Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) is about 10 times more common worldwide. Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) doesn’t make people sick and doesn’t need to be treated.

Amebiasis diagnosis may involve:

- Intestinal infection: Enzyme immunoassay of stool, molecular tests for parasite DNA in stool, microscopic examination, and/or serologic testing

- Extraintestinal infection: Imaging and serologic testing or a therapeutic trial with an amebicide

Nondysenteric amebiasis may be misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease, or diverticulitis. A right-sided colonic mass may also be mistaken for colon cancer, tuberculosis, actinomycosis (a rare subacute to chronic infection caused by the gram-positive filamentous non-acid fast anaerobic to microaerophilic bacteria, Actinomyces) or lymphoma.

Amebic dysentery (diarrhea with the presence of blood and mucus in the feces) may be confused with shigellosis, salmonellosis, schistosomiasis, or ulcerative colitis. In amebic dysentery, stools are usually less frequent and less watery than those in bacillary dysentery (a bacterial infection of the intestines usually caused by Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Escherichia coli (E. coli), characterized by bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever). Amebic dysentery characteristically contain tenacious mucus and flecks of blood 21. Unlike stools in shigellosis, salmonellosis, and ulcerative colitis, amebic stools do not contain large numbers of white blood cells because Entamoeba histolytica trophozoites breakdown white blood cells 21.

Hepatic amebiasis and amebic abscess must be differentiated from other liver infections (eg, echinococcal disease) and tumors 21. Patients with amebic liver abscess often present with right upper quadrant pain and fever 22, 23, 13. Amebic liver abscess is more common in men and younger adults exposed to endemic areas, whereas pyogenic liver abscess (a pus-filled pocket within the liver caused by a bacterial infection) is more common in older adults 21. Also, symptoms of echinococcosis also known as hydatid disease (a parasitic infection caused by tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus) are unusual until the cyst grows to 10 cm in diameter, and liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma) usually has no symptoms other than those caused by chronic liver disease. Imaging and laboratory tests and tissue biopsy are often needed to diagnose amebiasis. Testing typically includes complete blood count (CBC), liver tests, and abdominal CT. Patients with pyogenic liver abscess (a pus-filled pocket within the liver caused by a bacterial infection) often have left shift on white blood cell count, elevated serum bilirubin concentration, history of gallstones, and diabetes mellitus. Amebic liver abscess generally does not cause a left shift on white blood cell counts or elevated serum bilirubin concentration 21.

Diagnosis of amebiasis is supported by finding amebic trophozoites, cysts, or both in stool or tissues; however, pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) are morphologically indistinguishable from nonpathogenic Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar), as well as Entamoeba moshkovskii (E. moshkovskii) and Entamoeba bangladeshi (E. bangladeshi), which are of uncertain pathogenicity 21. Immunoassays that detect E. histolytica antigens in stool are sensitive and specific and are done to confirm the diagnosis 21. Specific DNA detection assays for E. histolytica using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are available at diagnostic reference laboratories and have very high sensitivity and specificity 21.

Serologic tests are positive in 21:

- About 95% of patients with an amebic liver abscess

- > 70% of those with active intestinal infection

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is the most widely used serologic test 21. Antibody titers can confirm E. histolytica infection but may persist for months or years, making it impossible to differentiate acute from past infection in residents from areas with a high prevalence of infection. Therefore, serologic tests are helpful when previous infection is considered less likely (eg, in travelers to endemic areas) 21.

If you think you have amebiasis, see a doctor. Amebiasis can be difficult to diagnose. Most people with amebiasis don’t get very sick. Everyone with amebiasis should receive antibiotics to treat the infection.

Amebiasis is treated with antibiotics such as oral tinidazole, metronidazole, secnidazole, or ornidazole 21. You will take one antibiotic if you’re not feeling sick. If you are sick, you’ll probably be prescribed a second antibiotic such as iodoquinol, paromomycin, or diloxanide furoate to take after you’ve finished the first for cyst eradication 21.

For gastrointestinal symptoms and extraintestinal amebiasis, one of the following taken orally is used 21:

- Metronidazole for 7 to 10 days

- Tinidazole for 3 days for mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms, 5 days for severe gastrointestinal symptoms, and 3 to 5 days for amebic liver abscess

- Secnidazole in a single dose

- Ornidazole for 5 days

Alcohol must be avoided because these medications may have a disulfiram-like effect or disulfiram reaction – an adverse reaction to alcohol that occurs when certain medications or substances are taken concurrently interfere with the breakdown of alcohol in the body, leading to a buildup of acetaldehyde, a toxic byproduct causing unpleasant symptoms similar to those experienced when disulfiram, a drug used to treat alcoholism, is taken with alcohol 24, 21.

Metronidazole is the mainstay of therapy for invasive amebiasis 25, 26, 27. Tinidazole has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for intestinal or extraintestinal amebiasis. Other nitroimidazoles with longer half-lives (i.e., secnidazole and ornidazole) are currently unavailable in the United States.

In terms of gastrointestinal adverse effects, tinidazole is generally better tolerated than metronidazole.

Nitazoxanide is an effective alternative for noninvasive intestinal amebiasis, but efficacy against invasive disease is not known; therefore, it should only be used if other treatments are contraindicated 28, 29. Nitroimidazole therapy leads to clinical response in approximately 90% of patients with mild-to-moderate amebic colitis. Because intraluminal parasites are not affected by nitroimidazoles, nitroimidazole therapy for amebic colitis should be followed by treatment with a luminal agent (eg, paromomycin or diloxanide furoate) to prevent a relapse 8. A 2019 Cochrane Database Review 30 reported that tinidazole may be more effective than metronidazole and is associated with fewer adverse events. Combination drug therapy may be more effective for reducing parasitological failure compared with metronidazole alone 30.

Clinical E histolytica isolates have demonstrated rising inhibitory concentrations to nitroimidazoles. If there is a slow clinical response to therapy or relapse following therapy, a more prolonged course of therapy or alternative treatment such as therapeutic aspiration and/or percutaneous catheter drainage may need to be considered 31.

Therapy for patients with significant gastrointestinal symptoms should include rehydration with intravenous (IV) fluid and electrolytes replacement other supportive measures.

Although metronidazole, tinidazole, and nitazoxanide have some activity against E. histolytica cysts, they are not sufficient to eradicate cysts. Consequently, a second oral medication is used to eradicate residual cysts in the intestine.

Options for E. histolytica cysts eradication are 21:

- Iodoquinol for 20 days

- Paromomycin for 7 days (safe for use in pregnancy)

- Diloxanide furoate for 10 days. Diloxanide furoate is not available commercially in the United States but may be obtained through some compounding pharmacies.

Asymptomatic E dispar infections should not be treated, but because this organism is a marker of fecal-oral contamination, educational efforts should be initiated 8.

Treatment is not necessary for asymptomatic E. moshkovskii and E. bangladeshi infections until more is known about their pathogenicity 21.

Pleuropulmonary infections should be treated by aspiration of amebic pleural effusion followed by antimicrobial therapy such as metronidazole with a luminal agent 32.

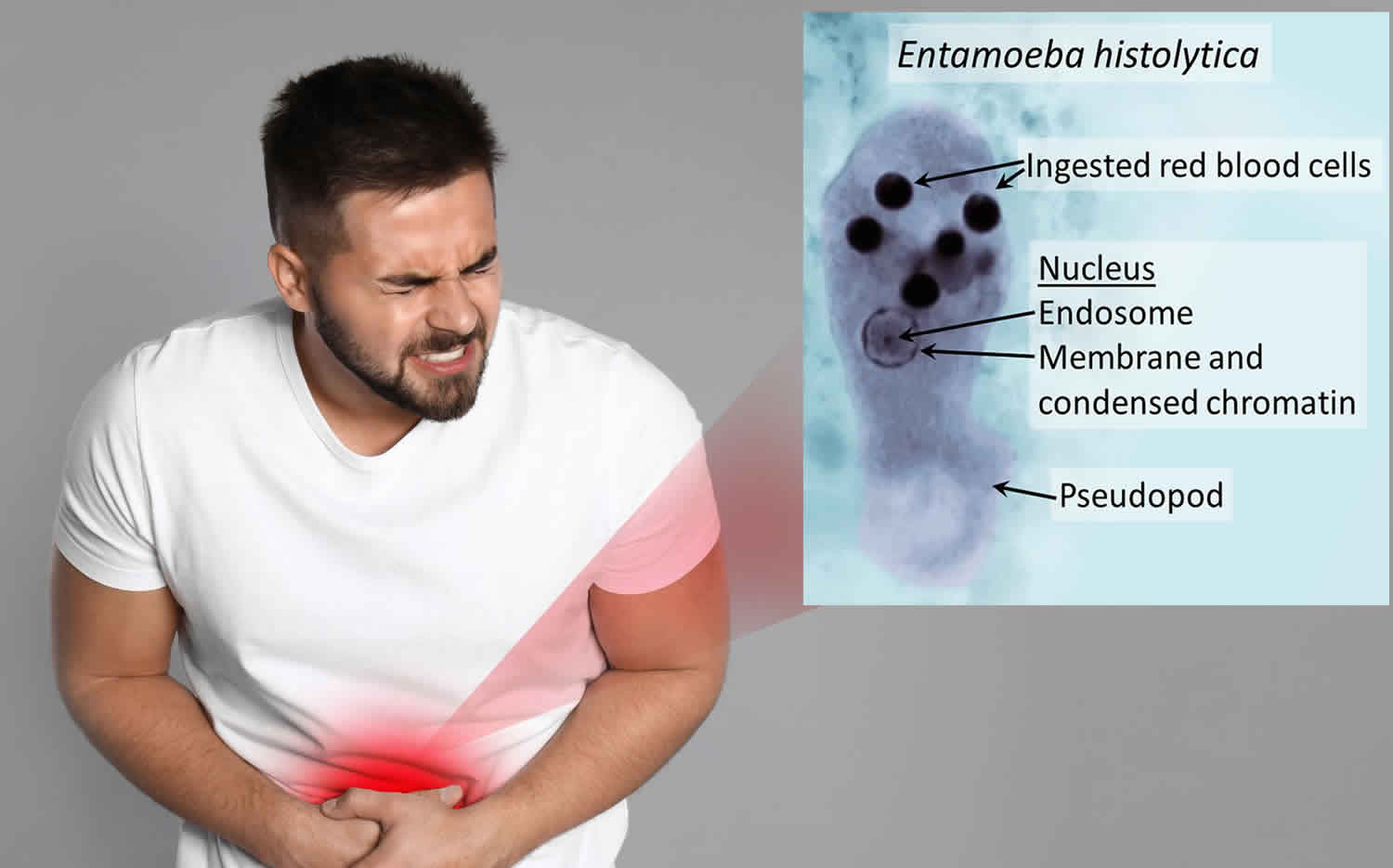

Figure 1. Entamoeba histolytica Trophozoite

Footnotes: This photomicrograph of a trichrome-stained specimen revealed the presence of an Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite, within which a number of ingested red blood cells (erythrocytes) could be seen as dark, round inclusions. The Entamoeba histolytica parasite shows nucleus that has the typical small, centrally located karyosome and thin, uniform peripheral chromatin.

[Source 33 ]Figure 2. Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) or Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) Cyst

Footnotes: Mature Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) or Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) cysts have 4 nuclei that characteristically have centrally-located karyosomes and fine, uniformly distributed peripheral chromatin. Cysts usually measure 12 to 15 µm. Cyst of Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) or Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) stained with trichrome. Three nuclei are visible in the focal plane (black arrows), and the cyst contains a chromatoid body with typically blunted ends (red arrow). The chromatoid body in this image is particularly well demonstrated.

[Source 34 ]How do you get amebiasis?

You get amebiasis when a parasite called Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) enters your digestive system. This happens when you eat or drink something that the parasite has contaminated. You can also get the parasite in your system if you touch a surface containing the parasite’s eggs and then put your fingers in your mouth.

Amebiasis usually spreads through contact with feces (poop or stool). You’re at higher risk for amebiasis infection if you:

- Engage in anal sex.

- Live with other people in a place that has poor sanitary conditions.

- Travel to places with poor sanitation.

Is amebiasis contagious?

Amebiasis is contagious. You can get it after:

- Exposure to E. histolytica through someone else’s infected stool.

- Eating or drinking contaminated water or food.

What other conditions put me at higher risk for amebiasis?

You’re at higher risk for contracting a severe amebiasis infection if 35:

- Children, especially neonates

- Pregnant and postpartum women

- Have cancer.

- Have HIV infection

- Have poor nutrition.

- Take corticosteroids.

What can I expect if I have amebiasis?

If you have amebiasis, take the antibiotics prescribed by your doctor. Treatment can cure amebiasis. But left untreated, amebiasis can be fatal. Talk to your doctor if you recently traveled and started having symptoms.

Can I go to work or school if I have amebiasis?

You or your child should stay home if you have diarrhea. Wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom or handling diapers. Talk to your doctor about when you or your child can return to work, child care or school once you have begun taking antibiotics.

What cause amebiasis?

Amebiasis also known as amebic dysentery is a gastrointestinal illness caused by a pseudopod-forming, nonflagellated protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) 1. Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) parasite has a two-stage life cycle, existing as either an infectious cyst or invasive trophozoite. Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) is spread via ingestion of Entamoeba histolytica cysts, most commonly by fecally contaminated food or water, or via direct fecal-oral transmission through sexual contact 8, 36. Amebiasis is more common in people living in and among travelers to these areas with poor sanitary conditions. Amebiasis can also affect men who have sex with men. Trophozoite invasion of the intestinal mucosa leading to mucosal inflammation is a hallmark of amebic colitis.

You can get amebiasis if you:

- Swallow something such as water or food contaminated with Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica).

- Put something in your mouth that has touched the poop of someone infected with Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica).

- Swallow Entamoeba histolytica parasite picked up from a contaminated surface or your fingers.

The majority of amebiasis infections restricted to the lumen of the intestine (“luminal amebiasis”) are asymptomatic 34. Invasive intestinal amebiasis also called amebic colitis occurs when the intestinal mucosa is invaded. Symptoms include severe dysentery (diarrheal disease characterized by bloody stool and mucus) and associated complications. Severe chronic infections may lead to further complications such as peritonitis, perforations, and the formation of amebic granulomas (ameboma).

Amebic liver abscesses are the most common manifestation of extraintestinal amebiasis. Pleuropulmonary abscess, brain abscess, and necrotic lesions on the perianal skin and genitalia have also been observed.

Risk factors for amebiasis

In the United States, amebiasis is most common in 7:

- People who traveled to tropical places with poor sanitary conditions

- Immigrants from tropical countries with poor sanitary conditions

- People who live in facilities with poor sanitary conditions

- People who have anal sex.

Amebiasis Pathophysiology

Entamoeba species exist in 2 forms 21, 37, 38, 39, 40:

- Cyst (infective form).

- Cysts predominate in formed stools and resist destruction in the external environment. Infection occurs following ingestion of amebic cysts. They may spread directly from person to person through fecal-oral transmission, including through oral-anal sexual contact, or indirectly via food or water. Cysts remain viable in the environment for weeks to months. After ingestion of a cyst, the ameba excysts to form a trophozoite in the colon.

- Trophozoite (form that causes invasive disease)

- The motile trophozoites feed on bacteria and tissue, reproduce, colonize the lumen and the mucosa of the large intestine, and sometimes invade tissues and organs. Trophozoites predominate in liquid stools but rapidly die outside the body and, if ingested, are killed by gastric acids. Some trophozoites in the colonic lumen become cysts that are excreted with stool.

- Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) trophozoites can adhere to and kill colonic epithelial cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes and can cause dysentery with blood and mucus but with few polymorphonuclear leukocytes in stool. Trophozoites also secrete proteases that degrade the extracellular matrix and permit invasion into the intestinal wall and beyond. Trophozoites can spread via the portal circulation and cause necrotic liver abscesses. Infection may spread by direct extension from the liver to the right pleural space, lung, or skin, or rarely through the bloodstream to the brain and other organs.

Pathogenesis of E. histolytica is multifactorial, since the virulent molecules of the parasite, as well as the host’s immune response, play an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease, causing damage to tissues that facilitate entry to systemic sites 41. The destructive mechanisms of E. histolytica include contact with target cells, cytolysis, and phagocytosis, and the degradation of ingested cells. After contact with trophozoites in the epithelium, the cells increase the paracellular permeability produced by the opening of the TJ junctions and the distortion of the microvilli 42. Superficial blisters and tiny focal discontinuities appear in the host plasma membrane, displacing and separating neighboring cells and compromising membrane integrity 43.

Entamoeba histolytica usually lodges in the intestine and in about 90 percent of cases, it generates an asymptomatic infection; however, it is not clear why a minority of individuals infected with E. histolytica activate a pathogenic phenotype 44. Throughout many years of study, the participation of pathogenic molecules involved in various causal events due to E. histolytica infection has been demonstrated. The most studied physiological events are: (1) the colonization of the intestinal mucus layer, (2) the adherence of trophozoites to the host intestinal epithelium, (3) the interaction with the intracellular junctions of the epithelium, (4) cytolysis, (5) phagocytosis and trogocytosis, (6) the activation of the host’s immune response, and (7) the contributions of the host gut microbiota 45, 43, 46, 47.

Amebiasis Life Cycle

Pathogenic Entamoeba species occur worldwide and are frequently recovered from fresh water contaminated with human feces 34. The majority of amebiasis cases occur in developing countries. In industrialized countries, people at risk of getting amebiasis include men who have sex with men, travelers, recent immigrants, immunocompromised persons, and institutionalized populations 34.

Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) parasite has a two-stage life cycle, existing as either an infectious cyst or invasive trophozoite. Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) is spread via ingestion of Entamoeba histolytica cysts, most commonly by fecally contaminated food or water, or via direct fecal-oral transmission through sexual contact 8, 36. Trophozoite invasion of the intestinal mucosa leading to mucosal inflammation is a hallmark of amebic colitis.

Entamoeba cysts and trophozoites are passed in feces (number 1). Cysts are typically found in formed stool, whereas trophozoites are typically found in diarrheal stool. Infection with Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar occurs via ingestion of mature cysts (number 2) from food, water, or hands contaminated with feces (poop). Exposure to infectious cysts and trophozoites in fecal matter during sexual contact may also occur. Excystation (number 3) occurs in the small intestine and trophozoites (number 4) are released, which migrate to the large intestine. Trophozoites may remain confined to the intestinal lumen (A: noninvasive infection) with individuals continuing to pass cysts in their stool (asymptomatic carriers). Trophozoites can invade the intestinal mucosa (B: intestinal disease), or blood vessels, reaching extraintestinal sites such as the liver causing amebic abscesses, as well as to the brain, lungs other extra-intestinal sites (C: extraintestinal disease). Trophozoites multiply by binary fission and produce cysts (number 5), and both stages are passed in the feces (number 1). Cysts can survive days to weeks in the external environment and remain infectious in the environment due to the protection conferred by their walls. Trophozoites passed in the stool are rapidly destroyed once outside the body, and if ingested would not survive exposure to the gastric environment.

Several properties of Entamoeba cyst help it to remain hardy in the environment for weeks, whereas trophozoites do not survive. For example, cysts are resistant to gastric acidity and are also relatively resistant to chlorine. The low infectious dose and environmental stability can predispose to the development of outbreaks 48, 49. Cysts can be killed by boiling.

Figure 3. Amebiasis Life Cycle

[Source 34 ]Amebiasis prevention

Washing your hands thoroughly with soap and water after going to the bathroom or changing diapers can help prevent spreading amebiasis to others. You should also wash your hands before handling or preparing food or drinks.

If you’re traveling in an area with poor sanitary conditions:

- DON’T eat or drink:

- Fountain drinks or any drinks with ice cubes

- Fresh fruit or vegetables you didn’t peel yourself

- Milk, cheese, and dairy products that may not have been pasteurized

- Food or drinks sold by street vendors

- It is safe to drink:

- Bottled water with an unbroken seal

- Carbonated (bubbly) water from sealed cans or bottles

- Carbonated drinks like soda from sealed cans or bottles

- Tap water that has been boiled for at least 1 minute

You also can make tap water safe to drink by first filtering it through an “absolute 1 micron or less” filter. Then dissolve chlorine, chlorine dioxide, or iodine tablets in the filtered water 7.

Amebiasis signs and symptoms

Many people infected with Entamoeba histolytica parasite or has amebiasis are asymptomatic but can chronically pass cysts in their stools. Only about 10% to 20% of people infected with Entamoeba histolytica become ill 20, 7. Even then, symptoms are often mild. Amebic colitis is the most common symptomatic manifestation of amebiasis, with variable presentation that can include watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, stomach cramping, nausea, and fever. A severe form of amebiasis called amebic dysentery can cause stomach pain, bloody poop (dysentery), fever, abdominal tenderness and rarely the formation of a tumor like granulation mass referred to as an ameboma 8, 50. Symptoms usually develop within 2 to 4 weeks after being infected with Entamoeba histolytica parasite but can show up later.

Fulminant amebic colitis, though uncommon, is the most serious and life-threatening complication of amebiasis, presenting initially with bloody diarrhea, fever, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count in the blood (leukocytosis) and abdominal pain 20. Intestinal necrosis, toxic megacolon, perforation and peritonitis may ensue 20. Fulminant amebic colitis is associated with high mortality and morbidity, with case fatality rates ranging from 40% to 89% 51, 52, 53, 54, 55.

Rarely, the Entamoeba histolytica parasite travels through your blood stream to your liver and forms amebic liver abscesses (collection of pus in your liver). In a small number of cases, the Entamoeba histolytica parasite can spread to other parts of your body, including the lungs and brain.

Intestinal amebiasis (amebic colitis)

Many people infected with Entamoeba histolytica parasite or has amebiasis are asymptomatic but can chronically pass cysts in their stools. Only about 10% to 20% of people infected with Entamoeba histolytica become ill 20, 7. Symptoms that occur with tissue invasion in the colon usually develop 1 to 3 weeks after ingestion of Entamoeba histolytica cysts and include:

- Intermittent diarrhea and constipation

- Flatulence (farting)

- Cramping abdominal pain

Tenderness over the liver or ascending colon and fever may occur, and stools may contain mucus and blood.

Amebic dysentery

Amebic dysentery presents with episodes of frequent semiliquid stools that often contain blood, mucus, and live trophozoites. Abdominal findings range from mild tenderness to frank abdominal pain, with high fevers and toxic systemic symptoms. Abdominal tenderness frequently accompanies amebic colitis. Sometimes, fulminant colitis complicated by toxic megacolon or peritonitis may develop.

Between relapses, symptoms diminish to recurrent cramps and loose or very soft stools, but emaciation and anemia may develop. Symptoms suggesting appendicitis may occur. Surgery in such cases may result in peritoneal spread of amebas.

Chronic amebic infection of the colon

The severe forms of amebiasis are colon ameboma, fulminant necrotizing colitis, and toxic megacolon 56. The appearance of symptoms, such as severe dysentery and pain with signs of peritoneal irritation (rebound), intense tenesmus, a fever (>100.4 °F [>38 °C]), fast heart rate (tachycardia), high blood pressure (hypertension), nausea, and anorexia, are suggestive of severe forms of intestinal amebiasis 57. The mortality rates of dysenteric syndrome due to E. histolytica are less than 1%, but mortality due to complications increases up to 75% 5. Fulminant amebic colitis is a rare complication of amebiasis associated with high mortality, and can occur in more than 50% of cases with severe colitis 57, 56. The severe forms of invasive amebiasis can be observed in young children, pregnant women, the elderly, and those with chronic diseases and individuals being treated with immunosuppressants or those with immunodeficiency disorders 39.

Chronic amebic infection of the colon can mimic inflammatory bowel disease and manifests as intermittent nondysenteric diarrhea with abdominal pain, mucus, flatulence, and weight loss. Chronic infection may also manifest as tender, palpable masses or annular lesions (amebomas) in the cecum and ascending colon. Ameboma may be mistaken for colonic cancer or pyogenic abscess.

Hepatic amebiasis (amebic liver abscess)

Extraintestinal amebic disease originates from infection in the colon and can involve any organ, but a liver abscess is the most common. Amebic liver abscess is a disease that can affect individuals of all ages; in some endemic areas, the incidence rates are higher in both children under 5 years and young adults. Males are also more prone to developing amebic hepatic abscesses than females (7:1 to 9:1) 5, 39. The reason for such a striking difference is not clear but thought to be due to factors such as hormonal effects and alcohol consumption 4.

Amebic liver abscess is usually single and in the right lobe. It can manifest in patients who have had no prior symptoms and may develop insidiously 21. The most common symptoms suggestive of amebic liver abscess are intermittent fever (100.4 °F [38 °C]), sweats, chills, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weakness, weight loss and pain or discomfort over the liver that increases during inspiration 2, 21. Pain also occasionally referred to the right shoulder and back. Nausea has also been referenced but diarrhea is only occasionally mentioned (50% of cases) 39, 40. Jaundice is unusual and low grade when present. The abscess may perforate into the subphrenic space, right pleural cavity, right lung, or other adjacent organs (eg, pericardium) 21.

Enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) can be detected during digital percussion of the liver area and is always related to the dimensions of the abscess; patients can also display peritoneal signs (abdominal guarding or rebound). The absence of intestinal noises, jaundice, and pleural or pericardial rub are symptoms that should elicit alarm related to the rupture or imminence of rupture of the hepatic abscess 58.

Brain amebiasis (amebic brain abscess)

Amebic brain abscess is rarely observed and almost only occur in patients who also have a liver abscess 21.

Cutaneous amebiasis

Skin lesions are occasionally observed, especially around the perineum and buttocks in chronic infection, and may also occur in traumatic or operative wounds 21.

Amebiasis complications

Complications of amebiasis can occur, especially when the infection isn’t treated. They include:

- Anemia – a condition in which the number of red blood cells or hemoglobin in the blood is lower than normal resulting in pallor and weariness

- Liver abscess.

- Lung amebiasis (pleuropulmonary amebiasis).

- Peritonitis – inflammation of the lining of your abdomen called the peritoneum that is often caused by an infection from a hole in the bowel..

Amebiasis diagnosis

If your doctor suspects you having intestinal amebiasis, your doctor will ask for a sample of your poop. You may be asked for several poop samples from different days. This is because Entamoeba histolytica parasite is not always found in every sample. Diagnosing amebiasis can be very difficult. Other parasites and cells can look very similar to Entamoeba histolytica parasite under a microscope.

Four species of Entamoeba are morphologically indistinguishable, but molecular techniques show that they are different species 21:

- Entamoeba histolytica (pathogenic)

- Entamoeba dispar (harmless colonizer, more common)

- Entamoeba moshkovskii (less common, evidence of potential pathogenicity is emerging) 59

- Entamoeba bangladeshi (less common, uncertain pathogenicity)

If you’ve been told that you have an Entamoeba histolytica infection but you’re feeling fine, you might be infected with a different parasite, Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar). Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) is about 10 times more common worldwide. Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) doesn’t make people sick and doesn’t need to be treated.

Amebiasis diagnosis may involve:

- Intestinal infection: Enzyme immunoassay of stool, molecular tests for parasite DNA in stool, microscopic examination, and/or serologic testing

- Extraintestinal infection: Imaging and serologic testing or a therapeutic trial with an amebicide

Some laboratories have tests that can tell if a person is infected with Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) or Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar). Fluid from liver abscesses can also be tested for Entamoeba histolytica.

Pathogenic Entamoeba species must be differentiated from other intestinal protozoa such as the nonpathogenic amebae (Entamoeba coli, Entamoeba hartmanni, Entamoeba gingivalis, Endolimax nana, Iodamoeba buetschlii) and the flagellate Dientamoeba fragilis 34. Morphologic differentiation among these is possible, but potentially complicated, based on morphologic characteristics of the cysts and trophozoites 34.

In culture, differential growth characteristics of Entamoeba moshkovskii may aid in distinguishing it from other species, but culture methods have important limitations – missing mixed infections, contamination, is labor-intensive and has limited availability 34. Historically, differentiation of Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar) and Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) was based on isoenzymatic or immunologic analysis, but these are no longer favored with the availability of effective molecular methods and are seldom performed. Molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are currently recommended for distinguishing pathogenic Entamoeba species 34.

Microscopic Detection

Microscopic identification of cysts and trophozoites in the stool is the common method for diagnosing pathogenic Entamoeba species. This can be accomplished using:

- Fresh stool: wet mounts and permanently stained preparations (e.g., trichrome).

- Concentrates from fresh stool: wet mounts, with or without iodine stain, and permanently stained preparations (e.g., trichrome). While useful for cysts, concentration methods may not be useful for demonstrating trophozoites.

- Microscopy also has a low sensitivity if only one stool sample is analyzed, and requires personnel trained in morphological diagnosis. Collection and analysis of three consecutive stool samples within ten days improves the chances for detection. Also, Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar), Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica), and Entamoeba moshkovskii (E. moshkovskii) are not distinguishable based on morphology.

Trophozoites can also be identified in aspirates or biopsy samples obtained during colonoscopy or surgery.

Immunodiagnosis

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits for Entamoeba histolytica antibody detection as well as enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits for Entamoeba histolytica antigen detection are commercially available in the United States 34. Entamoeba histolytica antibody detection is most useful in patients with extraintestinal disease (i.e., amebic liver abscess) when organisms are not generally found on stool examination. Entamoeba histolytica antibody detection is of limited diagnostic value on patients from highly endemic areas that are likely to have prior exposure and seroconversion, but may be of more use on patients from areas where pathogenic Entamoeba species are rare 34. Entamoeba histolytica antigen detection during active infections may be useful as an add-on to microscopic diagnosis in detecting parasites and can distinguish between pathogenic and nonpathogenic infections.

Antibody detection

The indirect hemagglutination (IHA) test has been replaced by commercially available enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test kits for routine serodiagnosis of amebiasis. Antigen consists of a crude soluble extract of axenically cultured organisms. The enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test detects antibody specific for Entamoeba histolytica in approximately 95% of patients with extraintestinal amebiasis, 70% of patients with active intestinal infection, and 10% of asymptomatic persons who are passing cysts of Entamoeba histolytica 34. If antibodies are not detectable in patients with an acute presentation of suspected amebic liver abscess, a second specimen should be drawn 7-10 days later 34. If the second specimen does not show seroconversion, other agents should be considered. Detectable Entamoeba histolytica-specific antibodies may persist for years after successful treatment, so the presence of antibodies does not necessarily indicate acute or current infection 34. Also, patients who have lived in highly endemic areas are likely to be seropositive due to past exposures. Specificity is 95% or higher: false-positive reactions rarely occur.

Although detection of IgM antibodies specific for E. histolytica has been reported, sensitivity is only about 64% in patients with current invasive disease 34. Several commercial enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits for E. histolytica antibody detection are available in the United States. No commercial antibody detection kits exist for E. dispar or E. moshkovskii or E. bangladeshi 34.

Antigen Detection

Antigen detection may be useful as an adjunct to microscopic diagnosis in detecting parasites and to distinguish between pathogenic and nonpathogenic infections. However, utility is limited for frozen or fixed specimens and for post-treatment specimens. Recent studies indicate improved sensitivity and specificity of fecal antigen assays with the use of monoclonal antibodies which can distinguish between E. histolytica and E. dispar infections. At least one commercial kit is available which detects only pathogenic E. histolytica infection in stool; several kits are available which detect E. histolytica antigens in stool but do not exclude E. dispar infections.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Conventional PCR

In reference diagnosis laboratories, molecular analysis by conventional PCR-based assays is the method of choice for discriminating between Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) and Entamoeba dispar (E. dispar). Some assays also can distinguish Entamoeba moshkovskii (E. moshkovskii) 34.

Real-Time PCR

A TaqMan real-time PCR approach has been validated at U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is used for differential laboratory diagnosis of amebiasis 34. The assay targets the small-subunit rRNA (18S rRNA) gene with species-specific TaqMan probes in a duplex format, making it possible to detect both E. histolyrica and E. dispar in the same reaction vessel 34, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64.

Amebic intestinal infection

Molecular analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for fecal antigens are most sensitive and differentiate E. histolytica from other amebas 21. Microscopic identification of intestinal amebas may require examination of 3 to 6 stool specimens and concentration methods. Antibiotics, antacids, antidiarrheals, enemas, and intestinal radiocontrast agents can interfere with recovery of the parasite and should not be given until the stool has been examined 21. E. histolytica is indistinguishable morphologically from E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, and E. bangladeshi but can be distinguished from a number of nonpathogenic microorganisms microscopically, including E. coli, E. hartmanni, E. polecki, Endolimax nana, and Iodamoeba bütschlii.

In symptomatic patients, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may show nonspecific inflammatory changes or characteristic flask-shaped mucosal lesions upon histologic exam. Lesions should be aspirated, and the aspirate should be examined for trophozoites and tested for specific E. histolytica antigen or DNA. Biopsy specimens from rectosigmoid lesions may also show trophozoites.

Amebic liver abscess

Amebic extraintestinal infection is more difficult to diagnose. Stool examination is usually negative, and recovery of trophozoites from aspirated pus is uncommon 21. If a liver abscess is suspected, ultrasonography, CT, or MRI should be done 21. They have similar sensitivity; however, no technique can differentiate amebic from pyogenic abscess with certainty 21.

Needle aspiration is reserved for the following 21:

- Those likely to be due to fungi or pyogenic bacteria

- Those in which rupture seems imminent

- Those that respond poorly to pharmacologic therapy

Abscesses contain thick, semifluid material ranging from yellow to chocolate-brown. A needle biopsy may show necrotic tissue, but motile amebas are difficult to find in abscess material, and amebic cysts are not present.

A therapeutic trial of an amebicide is often the most helpful diagnostic tool for an amebic liver abscess 21.

Amebiasis treatment

Amebiasis is treated with antibiotics such as oral tinidazole, metronidazole, secnidazole, or ornidazole 21. You will take one antibiotic if you’re not feeling sick. If you are sick, you’ll probably be prescribed a second antibiotic such as iodoquinol, paromomycin, or diloxanide furoate to take after you’ve finished the first for cyst eradication 21.

For gastrointestinal symptoms and extraintestinal amebiasis, one of the following taken orally is used 21:

- Metronidazole for 7 to 10 days

- Tinidazole for 3 days for mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms, 5 days for severe gastrointestinal symptoms, and 3 to 5 days for amebic liver abscess

- Secnidazole in a single dose

- Ornidazole for 5 days

Alcohol must be avoided because these medications may have a disulfiram-like effect or disulfiram reaction – an adverse reaction to alcohol that occurs when certain medications or substances are taken concurrently interfere with the breakdown of alcohol in the body, leading to a buildup of acetaldehyde, a toxic byproduct causing unpleasant symptoms similar to those experienced when disulfiram, a drug used to treat alcoholism, is taken with alcohol 24, 21.

Metronidazole is the mainstay of therapy for invasive amebiasis 25, 26, 27. Tinidazole has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for intestinal or extraintestinal amebiasis. Other nitroimidazoles with longer half-lives (i.e., secnidazole and ornidazole) are currently unavailable in the United States.

In terms of gastrointestinal adverse effects, tinidazole is generally better tolerated than metronidazole.

Nitazoxanide is an effective alternative for noninvasive intestinal amebiasis, but efficacy against invasive disease is not known; therefore, it should only be used if other treatments are contraindicated 28, 29. Nitroimidazole therapy leads to clinical response in approximately 90% of patients with mild-to-moderate amebic colitis. Because intraluminal parasites are not affected by nitroimidazoles, nitroimidazole therapy for amebic colitis should be followed by treatment with a luminal agent (eg, paromomycin or diloxanide furoate) to prevent a relapse 8. A 2019 Cochrane Database Review 30 reported that tinidazole may be more effective than metronidazole and is associated with fewer adverse events. Combination drug therapy may be more effective for reducing parasitological failure compared with metronidazole alone 30.

Clinical E histolytica isolates have demonstrated rising inhibitory concentrations to nitroimidazoles. If there is a slow clinical response to therapy or relapse following therapy, a more prolonged course of therapy or alternative treatment such as therapeutic aspiration and/or percutaneous catheter drainage may need to be considered 31.

Therapy for patients with significant gastrointestinal symptoms should include rehydration with intravenous (IV) fluid and electrolytes replacement other supportive measures.

Although metronidazole, tinidazole, and nitazoxanide have some activity against E. histolytica cysts, they are not sufficient to eradicate cysts. Consequently, a second oral medication is used to eradicate residual cysts in the intestine.

Options for E. histolytica cysts eradication are 21:

- Iodoquinol for 20 days

- Paromomycin for 7 days (safe for use in pregnancy)

- Diloxanide furoate for 10 days. Diloxanide furoate is not available commercially in the United States but may be obtained through some compounding pharmacies.

The pathogenicity of E. moshkovskii and E. bangladeshi has been uncertain. They have been identified in stools primarily in children with and without diarrhea in impoverished areas where fecal contamination of food and water is present. Molecular diagnostic tests to identify them are available only in research settings. The optimal treatment is unknown, but they are likely to respond to medications used for E. histolytica. Given emerging data on the pathogenicity of E. moshkovskii 59, treatment for symptomatic infection can be considered using the same approach as for E. histolytica.

Pleuropulmonary infections should be treated by aspiration of amebic pleural effusion followed by antimicrobial therapy such as metronidazole with a luminal agent 32.

People without symptoms

People without symptoms who pass E. histolytica cysts, otherwise known as asymptomatic carriers, in non-endemic areas, should be treated with luminal agents that are minimally absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract such as paromomycin, iodoquinol and diloxanide furoate to prevent development of invasive disease and spreading elsewhere in the body and to others 65, 25, 66, 67, 8. In endemic areas, asymptomatic E. histolytica infections are not treated 68.

Asymptomatic E dispar infections should not be treated, but because this organism is a marker of fecal-oral contamination, educational efforts should be initiated 8.

Treatment is not necessary for asymptomatic E. moshkovskii and E. bangladeshi infections until more is known about their pathogenicity 21.

Amebic liver abscess treatment

Amebic liver abscess of up to 10 cm can be cured with metronidazole without drainage 69. Drainage is reserved for larger liver abscesses, for patients who do not exhibit a clinical response to medical therapy by about 72 hours or for left-lobe liver abscesses, which could rupture into the pericardium 68. Resolution of amebic liver abscess cavity on serial imaging takes months 14. Treatment with a luminal agent should also follow 8.

Amebic liver abscess treatment entails the use of a Nitroimidazole, preferably Metronidazole at a dose of 500 mg to 750 mg by mouth 3 times per day for 7 to10 days 4. Alternatively, Tinidazole 2 gm by mouth daily for 3 days can be used 4. Since the parasites can persist in the intestine in 40% to 60% of patients, treatment with a Nitroimidazole should always be followed with a luminal agent such as Paromomycin 500 mg 3 times a day for 7 days or Iodoquinol 650 mg three times a day for 20 days 70. Metronidazole and Paromomycin should not be given at the same time because diarrhea, a common side effect of paromomycin, can make assessing response to therapy difficult.

Options for E. histolytica cysts eradication are 21:

- Iodoquinol for 20 days

- Paromomycin for 7 days (safe for use in pregnancy)

- Diloxanide furoate for 10 days. Diloxanide furoate is not available commercially in the United States but may be obtained through some compounding pharmacies.

Chloroquine has also been used for patients with hepatic amebiasis. Dehydroemetine (available from the CDC Drug Service) has been successfully used but, because of its potential heart toxicity, is not preferred 68.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be added to treat bacterial superinfection in cases of fulminant amebic colitis and suspected perforation 68. Bacterial coinfection of amebic liver abscess has occasionally been observed (both before and as a complication of drainage), and adding antibiotics to the treatment regimen is reasonable in the absence of a prompt response to nitroimidazole therapy 68.

Unlike pyogenic liver abscess, uncomplicated amebic liver abscess generally responds to medical therapy alone; drainage is seldom necessary and is usually best avoided. When drainage is necessary, image-guided percutaneous intervention (ie, needle aspiration or catheter drainage) has replaced surgical intervention as the procedure of choice 71.

Around 15% of patients with amebic liver abscess fail medical treatment. In uncomplicated cases of amebic liver abscess, it has been shown that there is no benefit to drainage in addition to medical therapy 72. In situations where there is a lack of clinical response to antibiotic therapy, aspiration or catheter drainage may be necessary 8.

The indications for drainage of amebic liver abscess include the following 68:

- Presence of a left-lobe abscess more than 10 cm in diameter

- Impending rupture and abscess that does not respond to medical therapy within 3-5 days.

Therapeutic aspiration can be done either by percutaneous needle aspiration or by percutaneous catheter drainage. These options should be considered in patients with no clinical response to antibiotics within 5 to 7 days, in those with a high risk of abscess rupture (cavitary diameter over 5 cm or presence of lesions in the left lobe), or in cases of bacterial coinfection of amebic liver abscess 73. Between percutaneous needle aspiration and percutaneous catheter drainage, studies have shown that percutaneous catheter drainage is superior with higher success rate and quicker resolution 74.

Surgical and Percutaneous intervention

Surgical intervention is required for acute abdomen that is due to any of the following 52:

- Perforated amebic colitis

- Massive gastrointestinal bleeding

- Toxic megacolon (rare and typically associated with the use of corticosteroids)

Surgical intervention is usually indicated in the following clinical scenarios 8:

- Uncertain diagnosis (possibility of pyogenic liver abscess)

- Concern about bacterial suprainfection in amebic liver abscess

- Failure to respond to metronidazole after 4 days of treatment

- Empyema after amebic liver abscess rupture

- Large left-side amebic liver abscess representing risk of rupture in the pericardium

- Severely ill patient with imminent amebic liver abscess rupture.

Percutaneous catheter drainage improves treatment outcomes in amebic empyema and is life-saving in amebic pericarditis. It should be used judiciously in the setting of localized intra-abdominal fluid collections.

Amebiasis prognosis

Amebic infections can lead to significant illness while causing variable mortality. In terms of protozoan-associated mortality, amebiasis is second only to malaria 35. The severity of amebiasis is increased in the following groups 35:

- Children, especially neonates

- Pregnant and postpartum women

- Those using corticosteroids

- Those with cancers

- Malnourished individuals

Intestinal infections due to amebiasis generally respond well to appropriate antibiotics, though it should be kept in mind that previous infection and treatment will not protect against future colonization or recurrent invasive amebiasis 35.

Asymptomatic intestinal amebiasis occurs in 90% of infected individuals. However, only 4% to 10% of individuals with asymptomatic amebiasis who were monitored for 1 year eventually developed colitis or extraintestinal disease 75.

With the introduction of effective medical treatment, amebiasis mortality has fallen below 1% for patients with uncomplicated amebic liver abscess 35. The prognosis for most patients with an amebic liver abscess is excellent 76. However, amebic liver abscess can be complicated by sudden intraperitoneal rupture in 2-7% of patients, and this complication leads to a higher mortality 8. To avoid complications like rupture into the lung, pericardium, or abdomen, patients with amebic liver abscess need a prompt referral to an infectious disease expert for treatment. Current evidence reveals that drainage of complex abscess can improve outcomes as opposed to medical management 77.

Case-fatality rates associated with amebic colitis range from 1.9% to 9.1% 35. Amebic colitis evolves to fulminant necrotizing colitis or rupture in approximately 0.5% of cases; in such cases, mortality may exceeds 40% or even, according to some reports 50% 78.

Pleuropulmonary amebiasis has a 15%-20% mortality rate 35. Amebic pericarditis has a case-fatality rate of 40%. Cerebral amebiasis carries a very high mortality (90%) 35.

A study of 134 amebiasisrelated deaths in the United States from 1990 to 2007 found that mortality was highest in men, Hispanics, Asian/Pacific Islanders, and people aged 75 years or older 79. An association with HIV infection was also observed. Although deaths declined during the course of the study, more than 40% occurred in California and Texas 79. US-born persons accounted for the majority of amebiasis deaths; however, all of the fatalities in Asian/Pacific Islanders and 60% of the deaths in Hispanics were in foreign-born individuals 79.

- Shirley DT, Farr L, Watanabe K, Moonah S. A Review of the Global Burden, New Diagnostics, and Current Therapeutics for Amebiasis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 5;5(7):ofy161. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy161[↩][↩]

- Morán P, Serrano-Vázquez A, Rojas-Velázquez L, González E, Pérez-Juárez H, Hernández EG, Padilla MLA, Zaragoza ME, Portillo-Bobadilla T, Ramiro M, Ximénez C. Amoebiasis: Advances in Diagnosis, Treatment, Immunology Features and the Interaction with the Intestinal Ecosystem. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jul 21;24(14):11755. doi: 10.3390/ijms241411755[↩][↩]

- Chou A, Austin RL. Entamoeba histolytica Infection. [Updated 2023 Apr 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557718[↩]

- Jackson-Akers JY, Prakash V, Oliver TI. Amebic Liver Abscess. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430832[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Ximénez C., Morán P., Rojas L., Valadez A., Gómez A. Reassessment of the Epidemiology of Amebiasis: State of the Art. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2009;9:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.06.008[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Shirley D.-A.T., Farr L., Watanabe K., Moonah S. A Review of the Global Burden, New Diagnostics, and Current Therapeutics for Amebiasis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018;5:ofy161. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy161[↩][↩]

- Amebiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/amebiasis/about[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Stanley SL Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003 Mar 22;361(9362):1025-34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Swaminathan A, Torresi J, Schlagenhauf P, Thursky K, Wilder-Smith A, Connor BA, Schwartz E, Vonsonnenberg F, Keystone J, O’Brien DP; GeoSentinel Network. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers. J Infect. 2009 Jul;59(1):19-27. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.05.008[↩]

- Yang B, Chen Y, Wu L, Xu L, Tachibana H, Cheng X. Seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012 Jul;87(1):97-103. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0626[↩]

- Zhou F, Li M, Li X, Yang Y, Gao C, Jin Q, Gao L. Seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection among Chinese men who have sex with men. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 May 23;7(5):e2232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002232[↩]

- Kannathasan S, Murugananthan A, Kumanan T, Iddawala D, de Silva NR, Rajeshkannan N, Haque R. Amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka: first report of immunological and molecular confirmation of aetiology. Parasit Vectors. 2017 Jan 7;10(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1950-2[↩]

- Kannathasan S, Murugananthan A, Kumanan T, de Silva NR, Rajeshkannan N, Haque R, Iddawela D. Epidemiology and factors associated with amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jan 10;18(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5036-2[↩][↩]

- Cordel H, Prendki V, Madec Y, Houze S, Paris L, Bourée P, Caumes E, Matheron S, Bouchaud O; ALA Study Group. Imported amoebic liver abscess in France. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Aug 8;7(8):e2333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002333[↩][↩]

- Cui Z., Li J., Chen Y., Zhang L. Molecular Epidemiology, Evolution, and Phylogeny of Entamoeba spp. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;75:104018. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104018[↩]

- Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013 Jul 20;382(9888):209-22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2[↩]

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2095-128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0[↩][↩]

- Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, et al. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388(10051):1291-301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31529-X[↩]

- Diarrhoea. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/diarrhoeal-disease[↩]

- Shirley DA, Moonah S. Fulminant Amebic Colitis after Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Jul 28;10(7):e0004879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004879[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Amebiasis. https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/intestinal-protozoa-and-microsporidia/amebiasis[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Lardière-Deguelte S, Ragot E, Amroun K, Piardi T, Dokmak S, Bruno O, Appere F, Sibert A, Hoeffel C, Sommacale D, Kianmanesh R. Hepatic abscess: Diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg. 2015 Sep;152(4):231-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.01.013[↩]

- Wijewantha HS. Liver Disease in Sri Lanka. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2017 Jan-Jun;7(1):78-81. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1217[↩]

- Dang X, Wang R, Liu Y. Disulfiram-like Reaction With Ginaton: A Case Report and Literature Review. Clin Ther. 2023 Nov;45(11):1151-1154. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.08.013[↩][↩]

- Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG. Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;(2):CD006085. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 09;1:CD006085. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub3[↩][↩][↩]

- Kimura M, Nakamura T, Nawa Y. Experience with intravenous metronidazole to treat moderate-to-severe amebiasis in Japan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007 Aug;77(2):381-5.[↩][↩]

- Moon TD, Oberhelman RA. Antiparasitic therapy in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005 Jun;52(3):917-48, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.02.012[↩][↩]

- Rossignol JF, Kabil SM, El-Gohary Y, et al: Nitazoxanide in the treatment of amoebiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 101(10):1025-31, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.001[↩][↩]

- Escobedo AA, Almirall P, Alfonso M, et al: Treatment of intestinal protozoan infections in children. Arch Dis Child 94(6):478-82, 2009. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.151852[↩][↩]

- Gonzales MLM, Dans LF, Sio-Aguilar J. Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Jan 9;1(1):CD006085. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub3[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Singh A, Banerjee T, Shukla SK, Upadhyay S, Verma A. Creep in nitroimidazole inhibitory concentration among the Entamoeba histolytica isolates causing amoebic liver abscess and screening of andrographolide as a repurposing drug. Sci Rep. 2023 Jul 27;13(1):12192. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39382-1[↩][↩]

- Fung HB, Doan TL. Tinidazole: a nitroimidazole antiprotozoal agent. Clin Ther. 2005 Dec;27(12):1859-84. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.12.012[↩][↩]

- Entamoeba histolytica. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entamoeba_histolytica[↩]

- Amebiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/amebiasis[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Amebiasis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/212029-overview#a6[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Salit IE, Khairnar K, Gough K, Pillai DR. A possible cluster of sexually transmitted Entamoeba histolytica: genetic analysis of a highly virulent strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Aug 1;49(3):346-53. doi: 10.1086/600298[↩][↩]

- Ankri S. Entamoeba histolytica—Gut Microbiota Interaction: More Than Meets the Eye. Microorganisms. 2021;9:581. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030581[↩]

- Nagaraja S., Ankri S. Target Identification and Intervention Strategies against Amebiasis. Drug Resist. Updates. 2019;44:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.04.003[↩]

- Ximénez C., Morán P., Rojas L., Valadez A., Gómez A., Ramiro M., Cerritos R., González E., Hernández E., Oswaldo P. Novelties on Amoebiasis: A Neglected Tropical Disease. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2011;3:166. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.81695[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Mi-ichi F., Ikeda K., Tsugawa H., Deloer S., Yoshida H., Arita M. Stage-Specific De Novo Synthesis of Very-Long-Chain Dihydroceramides Confers Dormancy to Entamoeba Parasites. mSphere. 2021;6:e00174-21. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00174-21[↩][↩]

- Shahi P., Moreau F., Chadee K. Entamoeba histolytica Cyclooxygenase-Like Protein Regulates Cysteine Protease Expression and Virulence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019;8:447. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00447[↩]

- Betanzos A., Javier-Reyna R., García-Rivera G., Bañuelos C., González-Mariscal L., Schnoor M., Orozco E. The EhCPADH112 Complex of Entamoeba histolytica Interacts with Tight Junction Proteins Occludin and Claudin-1 to Produce Epithelial Damage. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065100[↩]

- Betanzos; Bañuelos; Orozco Host Invasion by Pathogenic Amoebae: Epithelial Disruption by Parasite Proteins. Genes. 2019;10:618. doi: 10.3390/genes10080618[↩][↩]

- Begum S., Gorman H., Chadha A., Chadee K. Role of Inflammasomes in Innate Host Defense against Entamoeba histolytica. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020;108:801–812. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MR0420-465R[↩]

- Carrero J.C., Reyes-López M., Serrano-Luna J., Shibayama M., Unzueta J., León-Sicairos N., De La Garza M. Intestinal Amoebiasis: 160 Years of Its First Detection and Still Remains as a Health Problem in Developing Countries. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020;310:151358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.151358[↩]

- Que X., Reed S.L. Cysteine Proteinases and the Pathogenesis of Amebiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:196–206. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.2.196[↩]

- Rawat A., Roy M., Jyoti A., Kaushik S., Verma K., Srivastava V.K. Cysteine Proteases: Battling Pathogenic Parasitic Protozoans with Omnipresent Enzymes. Microbiol. Res. 2021;249:126784. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126784[↩]

- Kasper MR, Lescano AG, Lucas C, Gilles D, Biese BJ, Stolovitz G, Reaves EJ. Diarrhea outbreak during U.S. military training in El Salvador. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040404[↩]

- Escolà-Vergé L, Arando M, Vall M, Rovira R, Espasa M, Sulleiro E, Armengol P, Zarzuela F, Barberá MJ. Outbreak of intestinal amoebiasis among men who have sex with men, Barcelona (Spain), October 2016 and January 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017 Jul 27;22(30):30581. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.30.30581[↩]

- Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA Jr. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 17;348(16):1565-73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710[↩]

- Alvi AR, Jawad A, Fazal F, Sayyed R. Fulminant amoebic colitis: a rare fierce presentation of a common pathology. Trop Doct. 2013 Apr;43(2):80-2. doi: 10.1177/0049475513491725[↩]

- Athié-Gutiérrez C, Rodea-Rosas H, Guízar-Bermúdez C, Alcántara A, Montalvo-Javé EE. Evolution of surgical treatment of amebiasis-associated colon perforation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010 Jan;14(1):82-7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1036-y[↩][↩]

- Nisheena R, Ananthamurthy A, Inchara YK. Fulminant amebic colitis: a study of six cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009 Jul-Sep;52(3):370-3. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.54997[↩]

- Chaturvedi R, Gupte PA, Joshi AS. Fulminant amoebic colitis: a clinicopathological study of 30 cases. Postgrad Med J. 2015 Apr;91(1074):200-5. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132597[↩]

- Takahashi T, Gamboa-Dominguez A, Gomez-Mendez TJ, Remes JM, Rembis V, Martinez-Gonzalez D, Gutierrez-Saldivar J, Morales JC, Granados J, Sierra-Madero J. Fulminant amebic colitis: analysis of 55 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997 Nov;40(11):1362-7. doi: 10.1007/BF02050824[↩]

- Tanaka E., Tashiro Y., Kotake A., Takeyama N., Umemoto T., Nagahama M., Hashimoto T. Spectrum of CT Findings in Amebic Colitis. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2021;39:558–563. doi: 10.1007/s11604-021-01088-7[↩][↩]

- Kantor M., Abrantes A., Estevez A., Schiller A., Torrent J., Gascon J., Hernandez R., Ochner C. Entamoeba histolytica: Updates in Clinical Manifestation, Pathogenesis, and Vaccine Development. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;2018:4601420. doi: 10.1155/2018/4601420[↩][↩]

- Martínez-Palomo A., Espinosa-Cantellano M., Tsutsumi G.R., Tsutsumi V. Amebic Liver Abscess. In: Muriel P., editor. Liver Pathophysiology: Therapies and Antioxidants. Academic Press; London, UK: 2017. pp. 181–186.[↩]

- Heredia RD, Fonseca JA, López MC. Entamoeba moshkovskii perspectives of a new agent to be considered in the diagnosis of amebiasis. Acta Trop. 2012 Sep;123(3):139-45. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.05.012[↩][↩]

- Qvarnstrom Y, James C, Xayavong M, Holloway BP, Visvesvara GS, Sriram R, da Silva AJ. Comparison of real-time PCR protocols for differential laboratory diagnosis of amebiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005 Nov;43(11):5491-7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5491-5497.2005[↩]

- Clark CG, Diamond LS. Differentiation of pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica from other intestinal protozoa by riboprinting. Arch Med Res. 1992;23(2):15-6.[↩]

- Evangelopoulos A, Spanakos G, Patsoula E, Vakalis N, Legakis N. A nested, multiplex, PCR assay for the simultaneous detection and differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in faeces. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000 Apr;94(3):233-40. doi: 10.1080/00034980050006401[↩]

- Katzwinkel-Wladarsch S, Loscher T, Rinder H. Direct amplification and differentiation of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Entamoeba histolytica DNA from stool specimens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994 Jul;51(1):115-8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.115[↩]

- Novati S, Sironi M, Granata S, Bruno A, Gatti S, Scaglia M, Bandi C. Direct sequencing of the PCR amplified SSU rRNA gene of Entamoeba dispar and the design of primers for rapid differentiation from Entamoeba histolytica. Parasitology. 1996 Apr;112 ( Pt 4):363-9. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066592[↩]

- Blessmann J, Tannich E. Treatment of asymptomatic intestinal Entamoeba histolytica infection. N Engl J Med. 2002 Oct 24;347(17):1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200210243471722[↩]

- Petri WA Jr, Singh U. Diagnosis and management of amebiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999 Nov;29(5):1117-25. doi: 10.1086/313493[↩]

- Salles JM, Salles MJ, Moraes LA, Silva MC. Invasive amebiasis: an update on diagnosis and management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007 Oct;5(5):893-901. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.5.893[↩]

- Amebiasis Treatment & Management. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/212029-treatment#d9[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Bammigatti C, Ramasubramanian NS, Kadhiravan T, Das AK. Percutaneous needle aspiration in uncomplicated amebic liver abscess: a randomized trial. Trop Doct. 2013 Jan;43(1):19-22. doi: 10.1177/0049475513481767[↩]

- Wuerz T, Kane JB, Boggild AK, Krajden S, Keystone JS, Fuksa M, Kain KC, Warren R, Kempston J, Anderson J. A review of amoebic liver abscess for clinicians in a nonendemic setting. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012 Oct;26(10):729-33. doi: 10.1155/2012/852835[↩]

- Jha AK, Das G, Maitra S, Sengupta TK, Sen S. Management of large amoebic liver abscess–a comparative study of needle aspiration and catheter drainage. J Indian Med Assoc. 2012 Jan;110(1):13-5.[↩]

- Chavez-Tapia NC, Hernandez-Calleros J, Tellez-Avila FI, Torre A, Uribe M. Image-guided percutaneous procedure plus metronidazole versus metronidazole alone for uncomplicated amoebic liver abscess. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21;(1):CD004886. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004886.pub2[↩]

- Waghmare M, Shah H, Tiwari C, Khedkar K, Gandhi S. Management of Liver Abscess in Children: Our Experience. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2017 Jan-Jun;7(1):23-26. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1206[↩]

- Cai YL, Xiong XZ, Lu J, Cheng Y, Yang C, Lin YX, Zhang J, Cheng NS. Percutaneous needle aspiration versus catheter drainage in the management of liver abscess: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2015 Mar;17(3):195-201. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12332[↩]

- Fotedar R, Stark D, Beebe N, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for Entamoeba species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007 Jul;20(3):511-32, table of contents. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00004-07[↩]

- Kale S, Nanavati AJ, Borle N, Nagral S. Outcomes of a conservative approach to management in amoebic liver abscess. J Postgrad Med. 2017 Jan-Mar;63(1):16-20. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.191004[↩]

- Lübbert C, Wiegand J, Karlas T. Therapy of Liver Abscesses. Viszeralmedizin. 2014 Oct;30(5):334-41. doi: 10.1159/000366579[↩]

- Aristizábal H, Acevedo J, Botero M. Fulminant amebic colitis. World J Surg. 1991 Mar-Apr;15(2):216-21. doi: 10.1007/BF01659055[↩]

- Gunther J, Shafir S, Bristow B, Sorvillo F. Short report: Amebiasis-related mortality among United States residents, 1990-2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011 Dec;85(6):1038-40. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0288[↩][↩][↩]