What is an anti inflammatory diet ?

There are two distinct types of inflammation. The first type is inflammation resulting in acute pain. This can be considered classical inflammation. A second type of inflammation can be described as chronic low-level inflammation that is below the threshold of pain. This can be termed “silent inflammation” 1. Today we know the inflammatory process is a complex interaction of both the pro- and anti-inflammatory phases 2, 3. Inflammation acts as both a ‘friend and foe’: it is an essential component of immunosurveillance and host defence, yet a chronic low-grade inflammatory state is a pathological feature of a wide range of chronic conditions, such as the metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease) 4, 5. Although the association between inflammation and chronic conditions is widely recognised, the issue of causality and the degree to which inflammation contributes and serves as a risk factor for the development of disease remain unresolved.

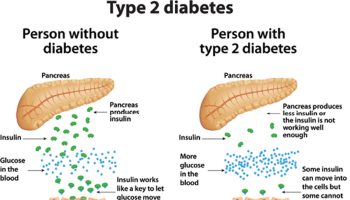

Age is the leading risk factor for many devastating diseases such as acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases, degenerative musculoskeletal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease 6. Increasing evidence suggests that systemic low grade inflammation is a contributing factor in age-related diseases like cancer, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases or even aging in general 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. More recently with increasing obesity, type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance amongst the younger population, metabolic syndrome, a constellation of risk factors associated with high blood sugar, accumulation of fat around the waist, high blood pressure, obesity, dyslipidemia (high triglyceride, high blood cholesterol and low HDL”good” cholesterol) and cardiovascular risk 12, 13, is increasing to an epidemic prevalence. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease are widely recognized as conditions of chronic inflammation, characterized by subclinical elevations in circulating plasma concentrations of inflammatory proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP) 14, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1), and fibrinogen 15, 16. There are several events that can turn on inflammatory responses. The most obvious is microbial invasion. Injuries and burns (both chemical and radiation) can also induce the most basic components of the inflammatory response. However, we are now beginning to understand how diet can also activate the same inflammatory responses induced by microbes. There is a great interest in identifying the best lifestyle approach for these patients to reduce the clinical and economical impact of inflammation and metabolic disorders.

It is very difficult to discuss a concept of silent inflammation if you cannot measure it, especially since there is no pain associated with it. It is only recently that new clinical markers of silent inflammation have emerged. The first of these clinical markers is high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). High sensitivity serum C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), plasma interleukin 6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2 (TNF-α-R2) are markers of systemic inflammation in the body, and have been associated with many chronic diseases, including coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease) 17, 18, 19, metabolic syndrome 20, diabetes mellitus 21, and cancer 22.

As inflammation has become increasingly recognized as having a role in cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, there is reason to explore how diet relates to subclinical inflammation, because nutrition interventions could be used to modify inflammatory protein concentrations.

What foods cause inflammation in the body

Inflammation is the common link among the leading causes of death. Together, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes account for almost 70% of all deaths in the United States; these diseases share inflammation as a common link 23, 24. Dietary patterns high in refined starches, sugar, and saturated and trans-fatty acids, poor in natural antioxidants and fiber from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and poor in omega-3 fatty acids may cause an activation of the innate immune system, most likely by excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines associated with a reduced production of anti-inflammatory cytokines 25. Dietary strategies clearly influence inflammation, as documented through both prospective observational studies as well as randomized controlled feeding trials in which participants agree to eat only the food provided to them 23, 26. Studies have shown how various dietary components can modulate key pathways to inflammation including sympathetic activity, oxidative stress, transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation, and proinflammatory cytokine production 27. Circulating markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, and some interleukins (IL-6, IL-18), correlate with propensity to develop coronary heart disease and heart attacks 28, 29, 30. Previous studies have also shown that depression is associated with upregulated inflammatory response, characterized by increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and other acute-phase proteins 31.

Diets that promote inflammation are 23:

- High in Refined Starches or Refined Carbs,

- High in Sugar,

- High in Saturated and Trans-fats,

- High in Salt (sodium),

- Alcohol,

- Food Additives,

- Low in omega-3 fatty acids,

- Low in natural antioxidants,

- Low in fiber from fruits,

- Low in vegetables, and

- Low in whole grains.

Dietary patterns high in refined starches, sugar, and saturated and trans-fatty acids, poor in natural antioxidants and fiber from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and poor in omega-3 fatty acids – aka the Average American Diet – may cause an activation of the innate immune system, most likely by an excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines associated with a reduced production of anti-inflammatory cytokines 32.

An Americanization of food habits has been recognized throughout the world, characterized by a high-energy diet, with increasing consumption of industrially processed foods. These foods usually contain large amounts of salt, simple sugars, saturated and trans fats, which food industries offer in response to consumers’ demands. Consequently, the intake of complex carbohydrates, fibres, fruits and vegetables has decreased. The energy and animal proteins consumed largely exceed World Health Organization recommendations, while, generally, a smaller variety of foods is being consumed.

- Most Americans exceed the recommendations for added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium. Most people say that if there is a healthy choice on a menu they will take it. But observations and research show this is generally not the case. Instead, people tend to make choices based on how food tastes. Typically, the more sugar, salt and fat in the food, the more we will like it.

- About three-fourths of the population has an eating pattern that is low in vegetables, fruits, dairy, and oils.

- More than half of the population is meeting or exceeding total grain and total protein foods recommendations, but, are not meeting the recommendations for the subgroups within each of these food groups.

The typical eating patterns currently consumed by many in the United States do not align with the Healthy Dietary Guidelines. As shown in Figure 1, when compared to the healthy eating pattern:

- About three-fourths of the population has an eating pattern that is low in vegetables, fruits, dairy, and oils.

- Most Americans exceed the recommendations for added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium.

Figure 1. The Average American Diet containing foods that can cause inflammation

In addition, the eating patterns of many are too high in calories. Calorie intake over time, in comparison to calorie needs, is best evaluated by measuring body weight status. The high percentage of the population that is overweight or obese suggests that many in the United States over consume calories. More than two-thirds of all adults and nearly one-third of all children and youth in the United States are either overweight or obese.

The typical American diet is about 50% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 35% fat. The Standard American Diet or “Western-style” dietary patterns with more red meat or processed meat, sugared drinks, sweets, refined carbohydrates, or potatoes-have been linked to obesity 33, 34, 35, 36. The Average American (Western-style) dietary pattern is also linked to increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

Meal frequency and snacking have increased over the past 30 years in the U.S. 37 on average, children get 27 percent of their daily calories from snacks, primarily from desserts and sugary drinks, and increasingly from salty snacks and candy.

What Americans Eat: Top 10 sources of calories in the U.S. diet

- Grain-based desserts (cakes, cookies, donuts, pies, crisps, cobblers, and granola bars)

- Yeast breads

- Chicken and chicken-mixed dishes

- Soda, energy drinks, and sports drinks

- Pizza

- Alcoholic beverages

- Pasta and pasta dishes

- Mexican mixed dishes

- Beef and beef-mixed dishes

- Dairy desserts(Source: Report of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee)

For the 20-30 year old the top sources of “Nutrition” are:

- Regular soft drinks 8.8% of total energy

- Pizza 5.1% of total energy

- Beer 3.9%

- Hamburgers and meat loaf 3.4%

- White bread 3.3%

- Cake, doughnuts and pastries 3.3%

- French fries and fried potatos 3.0%

- Potato chips, corn chips and popcorn 2.7%

- Rice 2.6%

- Cheese and cheese spread 2.5%

Since the above list of diets cause inflammation, therefore the main dietary strategy to reduce inflammation should include adequate omega-3 fatty acids intake, reduction of saturated and trans-fats, and consumption of a diet high in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains and low in refined grains. The whole diet approach seems particularly promising to reduce the inflammation associated with the metabolic syndrome (e.g. high “bad” triglyceride, low “good” HDL cholesterol, belly fat, high blood pressure, high blood sugar/insulin resistance). The choice of healthy sources of carbohydrate, fat, and protein, associated with regular physical activity and avoidance of smoking, is critical to fighting the war against chronic disease. Western dietary patterns warm up inflammation, while healthy dietary patterns cool it down.

Refined Starches or Refined Carbs Inflammatory Foods

The process of refining a food not only removes the fiber, but it also removes much of the food’s nutritional value, including B-complex vitamins, healthy oils and fat-soluble vitamins. Refined carbohydrates are plant-based foods that have the whole grain extracted during processing, where the fibers, starches, vitamins and minerals have been removed, leaving behind refined carbohydrates. Refined carbohydrates sources include bottled fruit juices, juice concentrates, white bread, pastries, sodas, donuts, cakes, cookies, sweets, chips and other highly processed or refined foods. These items contain easily digested carbohydrates that may contribute to weight gain, interfere with weight loss, and promote diabetes and heart disease 38.

Refined carbohydrates are composed of sugars (such as fructose and glucose) which have simple chemical structures composed of only one sugar (monosaccharides) or two sugars (disaccharides). Simple carbohydrates are easily and quickly utilized for energy by the body because of their simple chemical structure, often leading to a faster rise in blood sugar and insulin secretion from the pancreas – which can have negative health effects.

When it comes to carbohydrates, what’s most important is the type of carbohydrate you choose to eat because some sources are healthier than others. The amount of carbohydrate in the diet – high or low – is less important than the type of carbohydrate in the diet. For example, healthy, whole grains such as whole wheat bread, rye, barley and quinoa are better choices than highly refined white bread or French fries. For example, whole grain whole wheat flour.

Typically, foods with highly processed refined carbohydrates (eg, white bread) are digested at a much faster rate and have higher glycemic index (high GI) values than do more compact granules (low-starch gelatinization) and high amounts of viscose soluble fiber (eg, barley, oats, and rye) foods. These refined carbohydrates are more rapidly attacked by digestive enzymes due to grinding or milling that reduces particle size and removes most of the bran and the germ. Numerous epidemiologic studies have found that higher intake of refined carbohydrates (reflected by increased dietary Glycemic Load) is associated with greater risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, whereas higher consumption of whole grains protects against these conditions 39.

Table 1. List of refined carbs for more than 100 common foods with their glycemic index and glycemic load, per serving.

| FOOD | Glycemic index (glucose = 100) | Serving size (grams) | Glycemic load per serving |

| BAKERY PRODUCTS AND BREADS | |||

| Banana cake, made with sugar | 47 | 60 | 14 |

| Banana cake, made without sugar | 55 | 60 | 12 |

| Sponge cake, plain | 46 | 63 | 17 |

| Vanilla cake made from packet mix with vanilla frosting (Betty Crocker) | 42 | 111 | 24 |

| Apple muffin, made with rolled oats and sugar | 44 | 60 | 13 |

| Apple muffin, made with rolled oats and without sugar | 48 | 60 | 9 |

| Waffles, Aunt Jemima® | 76 | 35 | 10 |

| Bagel, white, frozen | 72 | 70 | 25 |

| Baguette, white, plain | 95 | 30 | 14 |

| Coarse barley bread, 80% kernels | 34 | 30 | 7 |

| Hamburger bun | 61 | 30 | 9 |

| Kaiser roll | 73 | 30 | 12 |

| Pumpernickel bread | 56 | 30 | 7 |

| 50% cracked wheat kernel bread | 58 | 30 | 12 |

| White wheat flour bread, average | 75 | 30 | 11 |

| Wonder® bread, average | 73 | 30 | 10 |

| Whole wheat bread, average | 69 | 30 | 9 |

| 100% Whole Grain® bread (Natural Ovens) | 51 | 30 | 7 |

| Pita bread, white | 68 | 30 | 10 |

| Corn tortilla | 52 | 50 | 12 |

| Wheat tortilla | 30 | 50 | 8 |

| BEVERAGES | |||

| Coca Cola® (US formula) | 63 | 250 mL | 16 |

| Fanta®, orange soft drink | 68 | 250 mL | 23 |

| Lucozade®, original (sparkling glucose drink) | 95 | 250 mL | 40 |

| Apple juice, unsweetened | 41 | 250 mL | 12 |

| Cranberry juice cocktail (Ocean Spray®) | 68 | 250 mL | 24 |

| Gatorade, orange flavor (US formula) | 89 | 250 mL | 13 |

| Orange juice, unsweetened, average | 50 | 250 mL | 12 |

| Tomato juice, canned, no sugar added | 38 | 250 mL | 4 |

| BREAKFAST CEREALS AND RELATED PRODUCTS | |||

| All-Bran®, average | 44 | 30 | 9 |

| Coco Pops®, average | 77 | 30 | 20 |

| Cornflakes®, average | 81 | 30 | 20 |

| Cream of Wheat® | 66 | 250 | 17 |

| Cream of Wheat®, Instant | 74 | 250 | 22 |

| Grape-Nuts® | 75 | 30 | 16 |

| Muesli, average | 56 | 30 | 10 |

| Oatmeal, average | 55 | 250 | 13 |

| Instant oatmeal, average | 79 | 250 | 21 |

| Puffed wheat cereal | 80 | 30 | 17 |

| Raisin Bran® | 61 | 30 | 12 |

| Special K® (US formula) | 69 | 30 | 14 |

| GRAINS | |||

| Pearled barley, average | 25 | 150 | 11 |

| Sweet corn on the cob | 48 | 60 | 14 |

| Couscous | 65 | 150 | 9 |

| Quinoa | 53 | 150 | 13 |

| White rice, boiled, type non-specified | 72 | 150 | 29 |

| Quick cooking white basmati | 63 | 150 | 26 |

| Brown rice, steamed | 50 | 150 | 16 |

| Parboiled Converted white rice (Uncle Ben’s®) | 38 | 150 | 14 |

| Whole wheat kernels, average | 45 | 50 | 15 |

| Bulgur, average | 47 | 150 | 12 |

| COOKIES AND CRACKERS | |||

| Graham crackers | 74 | 25 | 13 |

| Vanilla wafers | 77 | 25 | 14 |

| Shortbread | 64 | 25 | 10 |

| Rice cakes, average | 82 | 25 | 17 |

| Rye crisps, average | 64 | 25 | 11 |

| Soda crackers | 74 | 25 | 12 |

| DAIRY PRODUCTS AND ALTERNATIVES | |||

| Ice cream, regular, average | 62 | 50 | 8 |

| Ice cream, premium (Sara Lee®) | 38 | 50 | 3 |

| Milk, full-fat, average | 31 | 250 mL | 4 |

| Milk, skim, average | 31 | 250 mL | 4 |

| Reduced-fat yogurt with fruit, average | 33 | 200 | 11 |

| FRUITS | |||

| Apple, average | 36 | 120 | 5 |

| Banana, raw, average | 48 | 120 | 11 |

| Dates, dried, average | 42 | 60 | 18 |

| Grapefruit | 25 | 120 | 3 |

| Grapes, black | 59 | 120 | 11 |

| Oranges, raw, average | 45 | 120 | 5 |

| Peach, average | 42 | 120 | 5 |

| Peach, canned in light syrup | 52 | 120 | 9 |

| Pear, raw, average | 38 | 120 | 4 |

| Pear, canned in pear juice | 44 | 120 | 5 |

| Prunes, pitted | 29 | 60 | 10 |

| Raisins | 64 | 60 | 28 |

| Watermelon | 72 | 120 | 4 |

| BEANS AND NUTS | |||

| Baked beans | 40 | 150 | 6 |

| Black-eyed peas | 50 | 150 | 15 |

| Black beans | 30 | 150 | 7 |

| Chickpeas | 10 | 150 | 3 |

| Chickpeas, canned in brine | 42 | 150 | 9 |

| Navy beans, average | 39 | 150 | 12 |

| Kidney beans, average | 34 | 150 | 9 |

| Lentils | 28 | 150 | 5 |

| Soy beans, average | 15 | 150 | 1 |

| Cashews, salted | 22 | 50 | 3 |

| Peanuts | 13 | 50 | 1 |

| PASTA and NOODLES | |||

| Fettucini | 32 | 180 | 15 |

| Macaroni, average | 50 | 180 | 24 |

| Macaroni and Cheese (Kraft®) | 64 | 180 | 33 |

| Spaghetti, white, boiled, average | 46 | 180 | 22 |

| Spaghetti, white, boiled 20 min | 58 | 180 | 26 |

| Spaghetti, whole-grain, boiled | 42 | 180 | 17 |

| SNACK FOODS | |||

| Corn chips, plain, salted | 42 | 50 | 11 |

| Fruit Roll-Ups® | 99 | 30 | 24 |

| M & M’s®, peanut | 33 | 30 | 6 |

| Microwave popcorn, plain, average | 65 | 20 | 7 |

| Potato chips, average | 56 | 50 | 12 |

| Pretzels, oven-baked | 83 | 30 | 16 |

| Snickers Bar®, average | 51 | 60 | 18 |

| VEGETABLES | |||

| Green peas | 54 | 80 | 4 |

| Carrots, average | 39 | 80 | 2 |

| Parsnips | 52 | 80 | 4 |

| Baked russet potato | 111 | 150 | 33 |

| Boiled white potato, average | 82 | 150 | 21 |

| Instant mashed potato, average | 87 | 150 | 17 |

| Sweet potato, average | 70 | 150 | 22 |

| Yam, average | 54 | 150 | 20 |

| MISCELLANEOUS | |||

| Hummus (chickpea salad dip) | 6 | 30 | 0 |

| Chicken nuggets, frozen, reheated in microwave oven 5 min | 46 | 100 | 7 |

| Pizza, plain baked dough, served with parmesan cheese and tomato sauce | 80 | 100 | 22 |

| Pizza, Super Supreme (Pizza Hut®) | 36 | 100 | 9 |

| Honey, average | 61 | 25 | 12 |

The complete list of the glycemic index and glycemic load for more than 1,000 foods can be found in the article “International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008” by Fiona S. Atkinson, Kaye Foster-Powell, and Jennie C. Brand-Miller in the December 2008 issue of Diabetes Care, Vol. 31, number 12, pages 2281-2283 40.

List of refined carbs

Any foods that have been processed for quick consumption.

- Foods made with refined or “white” flour also contain less fiber and protein than whole-grain products.

- Snacks, such as crisps, sausage rolls, pies and pasties

- Granola bars

- Ice cream

- Donuts

- Cakes

- Twinkies

- Pastries

- Canned fruits with added sugar or syrup

- Sweets

- Fruit drinks

- Colas and carbonated sweetened beverages

- Energy drinks

- Sports drink

- Jams

- Crackers

- Dressings

- Sauces

- Cookies

- Fruit chews

- Pizzas

- Apple pies

- Anything with added sugar.

Sugar by Any Other Name

You don’t always see the word “sugar” on a food label. It sometimes goes by another name, like these:

- White sugar

- Brown sugar

- Raw sugar

- Agave nectar

- Brown rice syrup

- Corn syrup

- Corn syrup solids

- Coconut sugar

- Coconut palm sugar

- High-fructose corn syrup

- Invert sugar

- Dextrose

- Anhydrous dextrose

- Crystal dextrose

- Dextrin

- Evaporated cane juice

- Fructose sweetener

- Liquid fructose

- Glucose

- Lactose

- Honey

- Malt syrup

- Maple syrup

- Molasses

- Pancake syrup

- Sucrose

- Trehalose

- Turbinado sugar

Watch out for items that list any form of sugar in the first few ingredients.

Anti inflammatory diet research

Whole grains are healthier than refined grains because the process of refining carbohydrates results in the elimination of much of the fiber, vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients, and essential fatty acids 23. Furthermore, refined starches and sugars can rapidly alter blood glucose and insulin levels 23 and postprandial hyperglycemia can increase production of free radicals as well as proinflammatory cytokines 41.

There is consistent evidence that consumption of whole grains is protective against incident type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease 42, 43. However, it is unclear how these protective effects are mediated. Dietary fiber intake may reduce the risk of these diseases by mediating the pro-inflammatory process 44, 45. Two mechanistic hypotheses have emerged. First, dietary fiber may decrease oxidation of glucose and lipids, while maintaining a healthy intestinal environment. Second, dietary fiber may prevent inflammation by altering adipocytokines in adipose tissue and increasing enterohepatic circulation of lipids and lipophilic compounds 46. The link between dietary fiber intake and reduced high sensitivity serum C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) has been observed in several recent studies, including two analyses using cross-sectional data from NHANES 1999–2000 47, 48, an analysis using a longitudinal cohort of 524 healthy adults 49 and a small clinical trial 50.

Various dietary components including long chain omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidant vitamins, plant flavonoids, prebiotics and probiotics have the potential to modulate predisposition to chronic inflammatory conditions. These components act through a variety of mechanisms including decreasing inflammatory mediator production through effects on cell signaling and gene expression (omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, plant flavonoids), reducing the production of damaging oxidants (vitamin E and other antioxidants), and promoting gut barrier function and anti-inflammatory responses (prebiotics and probiotics) 51. In a large Danish study 52 involving over 7000 men and women who were followed over 15 years (1982-1998). What that study found was that in both men and women who frequently consume wholemeal bread, vegetables, fruits, and fish, was associated with a better overall survival rate as well as better cardiovascular survival 52.

A low-fat diet (≤30% of total calories) is still considered by many physicians to be a healthy choice for both primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (coronary heart disease) 53. An unintended consequence of emphasizing low-fat diets may have been to promote unrestricted carbohydrate intake, which reduces high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL “good” cholesterol) and raises triglyceride levels, exacerbating the metabolic manifestations of the insulin resistance syndrome, also known as the metabolic syndrome 54.

Three dietary strategies may help prevent coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease) 55:

- Increase consumption of omega-3 fatty acids from fish or plant sources;

- Substitute nonhydrogenated unsaturated fats for saturated and trans-fats; and

- Consume a diet high in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains and low in refined grains.

The effects of diet on coronary heart disease (coronary artery disease) can be mediated through multiple biologic pathways other than serum lipids, including oxidative stress, subclinical inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and thrombotic tendency 56.

Endothelial dysfunction is one of the mechanisms linking diet and the risk of cardiovascular disease 57, 58. This study 59 suggests a mechanism for the role of dietary patterns in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. For example, women in the Nurses’ Health Study who ate a “American” diet (high in red and processed meats, sweets, desserts, French fries, and refined grains) had higher proinflammatory cytokines (C-reactive protein, Interleukin-6, E-selectin, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1) than those with the “healthier” pattern, characterized by higher intakes of fruit, vegetables, legumes, fish, poultry, and whole grains 59. The levels of these mediators amplify the inflammatory response, are destructive and contribute to the clinical symptoms 51.

Arachidonic acid (AA) derived (omega-6) eicosanoids (primarily from refined vegetable oils such as corn, sunflower, and safflower) increase the production of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6, operating as precursors of the proinflammatory eicosanoids of the prostaglandin (PG)2-series 60. In contrast, the omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), found in fish, fish oil, walnuts, wheat germ, and some dietary supplements such as flax seed products can curb the production of Arachidonic acid (AA)-derived eicosanoids 61. The Omega-6 and Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) compete for the same metabolic pathways, and thus their balance is important 62. Accordingly, it is not surprising that both higher levels of Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) as well as lower Omega-6:Omega-3 ratios are associated with lower proinflammatory cytokine production 63.

Furthermore, in another study a healthy dietary pattern rich in fruit, vegetables and olive oil, such as the Mediterranean diet, is associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers, perhaps because of the anti-inflammatory properties of antioxidants 23.

The antioxidant properties of vegetables and fruits are thought to be one of the fundamental mechanisms underlying their anti-inflammatory dietary contributions 23. Oxidants such as superoxide radicals or hydrogen peroxide that are produced during the metabolism of food can activate the NF-κB pathway, promoting inflammation 64. Higher fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with lower oxidative stress and inflammation 64. In fact, some evidence suggests that the addition of antioxidants or vegetables may limit or even reverse proinflammatory responses to meals high in saturated fat 65.

To overcome silent inflammation requires an anti-inflammatory diet (with omega-3s and polyphenols). The most important aspect of such an anti-inflammatory diet is the stabilization of insulin and reduced intake of omega-6 fatty acids. The ultimate treatment lies in reestablishing hormonal and genetic balance to generate satiety instead of constant hunger. Anti-inflammatory nutrition with caloric restriction, should be considered as a form of gene silencing technology, in particular the silencing of the genes involved in the generation of silent inflammation. To this anti-inflammatory diet foundation supplemental omega-3 fatty acids at the level of 2–3 g of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) per day should be added. Finally, a diet rich in colorful, non-starchy vegetables would contribute adequate amounts of polyphenols to help not only to inhibit nuclear factor (NF)-κB (primary molecular target of inflammation) but also activate AMP kinase 66.

Table 2. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Foods EPA (Eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (Docosahexaenoic acid) – Fish and Seafood Sources

[Source 67]Table 3. Other sources of Omega-3 Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA) – Non-Seafood Sources

| Source of ALA | ALA content, g |

|---|---|

| Pumpkin seeds (1 tbsp) | 0.051 |

| Olive oil (1 tbsp) | 0.103 |

| Walnuts, black (1 tbsp) | 0.156 |

| Soybean oil (1 tbsp) | 1.231 |

| Rapeseed oil (1 tbsp) | 1.302 |

| Walnut oil (1 tbsp) | 1.414 |

| Flaxseeds (1 tbsp) | 2.350 |

| Walnuts, English (1 tbsp) | 2.574 |

| Flaxseed oil (1 tbsp) | 7.249 |

| Almonds (100 g) | 0.4 |

| Peanuts (100 g) | 0.003 |

| Beans, navy, sprouted (100 g) | 0.3 |

| Broccoli, raw (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Lettuce, red leaf (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Mustard (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Purslane (100 g) | 0.4 |

| Spinach (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Seaweed, spirulina, dried (100 g) | 0.8 |

| Beans, common, dry (100 g) | 0.6 |

| Chickpeas, dry (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Soybeans, dry (100 g) | 1.6 |

| Oats, germ (100 g) | 1.4 |

| Rice, bran (100 g) | 0.2 |

| Wheat, germ (100 g) | 0.7 |

| Avocados, California, raw (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Raspberries, raw (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Strawberries, raw (100 g) | 0.1 |

| Novel sources of ALA | ALA content, g |

| Breads and pasta (100 g) | 0.1–1.6 |

| Cereals (and granola bars) (55 g) | 1.0–4.9 |

| Eggs (50 g or 1 egg) | 0.1–0.6 |

| Processed meats (100 g) | 0.5 |

| Salad dressing (14 g – 31 g) | 2.0–4.0 |

| Margarine spreads (10 g – 100 g) | 0.3–1.0 |

| Nutrition bars (50 g) | 0.1–2.2 |

Footnote: 1 tablespoon (tbsp) oil = 13.6 g; 1 tbsp seeds or nuts = 12.35 g.

[Source 68]A traditional Mediterranean dietary pattern, which typically has a high ratio of monounsaturated (MUFA) and Omega-3 to Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFAs) and supplies an abundance of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and grains, has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects when compared with typical North American and Northern European dietary patterns in most observational and interventional studies 69.

The Mediterranean Diet is characterized by 70:

- An abundance of plant food (fruit, vegetables, breads, cereals, potatoes, beans, nuts, and seeds);

- Minimally processed, seasonally fresh, locally grown foods;

- Desserts comprised typically of fresh fruit daily and occasional sweets containing refined sugars or honey;

- Olive oil (high in polyunsaturated fat) as the principal source of fat;

- Daily dairy products (mainly cheese and yogurt) in low to moderate amounts;

- Fish and poultry in low to moderate amounts;

- Up to four eggs weekly;

- Red meat rarely; and

- Wine in low to moderate amounts with meals.

In studies involving people with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) has been used as an adjunct dietary therapy for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) 71. The goal of the anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) is to assist with a decreased frequency and severity of flares, obtain and maintain remission in people with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Dysbiosis, or altered bacterial flora, is one of the theories behind the development of anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID), in that certain carbohydrates in the lumen of the gut provide pathogenic bacteria a substrate on which to proliferate 72, 73.

The anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) has five basic components:

- The first of which is the modification of certain carbohydrates, (including lactose, and refined or processed complex carbohydrates)

- The second places strong emphasis on the ingestion of pre- and probiotics (e.g.; soluble fiber, leeks, onions, and fermented foods) to help restore the balance of the intestinal flora 74, 75, 76

- The third distinguishes between saturated, trans, mono- and polyunsaturated fats 77, 78,

- The fourth encourages a review of the overall dietary pattern, detection of missing nutrients, and identification of intolerances.

- The last component modifies the textures of the foods (e.g.; blenderized, ground, or cooked) as needed (per patient symptomology) to improve absorption of nutrients and minimize intact fiber.

The phases indicated in Table 4 are examples of the modification of texture complexity, so that dietitian and patient can expand the diet as the patient’s tolerance and absorption improves. Some sensitivities common to many patients (not just those with IBD), are eased through supplementation of digestive enzymes or avoidance. A senior dietitian advised the patient and either family or spouse regarding the details of the diet during regular clinic visits. Patients taking supplements (probiotics, vitamin/minerals, omega-3 fatty acids) were advised to continue or discontinue, depending on the needs of the individual and the dietary intake 79.

The anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) consists of lean meats, poultry, fish, omega-3, eggs, particular sources of carbohydrate, select fruits and vegetables, nut and legume flours, limited aged cheeses (made with active cultures and enzymes), fresh cultured yogurt, kefir, miso and other cultured products (rich with certain probiotics) and honey. Prebiotics, in the form of soluble fiber (containing beta-glucans and inulin, such as bananas, oats, blended chicory root, and flax meal) are suggested. In addition, the patient is advised to begin at a texture phase of the diet matching with symptomology, starting with phase one if in an active flare. Many patients require foods to be softened and textures mechanically altered by pureeing the foods, and avoiding foods with stems and seeds when starting the diet (see phases 1–3 of Table 4), as intact fiber can be problematic for those with strictures and highly active mucosal inflammation. Some patients will require lifelong avoidance of intact fiber. Food irritants are not limited to intact fiber, but may include certain foods, processing agents and flavorings to which IBD patients may be reactive.

Table 4. The Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID) Food Phase chart

| Phase type | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phase IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft, well-cooked or cooked then pureed foods, no seeds | Soft Textures: well-cooked or pureed foods, no seeds, choose floppy or tender foods | May still need to avoid stems, choose floppy greens or other greens depending on individual tolerance | If in remission with no strictures | |

| Vegetables | Butternut Squash, Pumpkin, Sweet Potatoes, Onions | Carrots, Zucchini, Eggplant, Peas, Snow peas, Spaghetti squash, Green beans, Yellow beans, Microgreens (2 week old baby greens), Watercress, Arugula, Fresh flat leaf parsley and cilantro, Seaweed, Algae | Butter lettuce, Baby spinach, Peeled cucumber, Olives, Leeks Bok Choy, Bamboo shoots, Collard greens, Beet greens, Sweet peppers, Kale, Fennel bulb | Artichokes, Asparagus, Tomatoes, Lettuce, Brussels sprouts, Beets, Cabbage, Kohlrabi, Rhubarb, Pickles, Spring onions, Water chestnuts, Celery, Celeriac, Cauliflower, Broccoli, Radish, Green pepper, Hot pepper |

| Pureed vegetables: Mushrooms, Phase II vegetables (pureed) | Pureed vegetables: all except cruciferous | Pureed vegetables: all from Phase IV, Kimchi | ||

| Fruits | Banana, Papaya, Avocado, Pawpaw | Watermelon (seedless), Mangoes, Honeydew, Cantaloupe, May need to be cooked: Peaches, Plums, Nectarines, Pears, (Phase III fruits are allowed if pureed and seeds are strained out) | Strawberries, Cranberries, Blueberries, Apricots, Cherries, Coconut, Lemons, Limes, Kiwi, Passion fruit, Blackberries, Raspberries, Pomegranate (May need to strain seeds from berries) | Grapes, Grapefruit, Oranges, Currants, Figs, Dates, Apples (best cooked), Pineapple, Prunes |

| Meats and fish | All fish (no bones), Sardines (small bones ok), Turkey and ground beef, Chicken, Eggs | Scallops | Lean cuts of Beef, Lamb, Duck, Goose | Shrimp, Prawns, Lobster |

| Non dairy unsweetened | Coconut milk, Almond milk, Oat milk, Soy milk | |||

| Dairy, unsweetened | Yogurt, Kefir | Farmers cheese (dry curd cottage cheese), Cheddar cheese | Aged cheeses | |

| Nuts/Oils/Legumes/Fats | Miso (refrigerated), Tofu, Olive oil, Canola oil, Flax oil, Hemp oil, Walnut oil, Coconut oil | Almond flour, Peanut flour, Soy flour, Sesame oil, Grapeseed oil, Walnut oil, Pureed nuts, Safflower oil, Sunflower oil | Whole nuts, Soybeans, Bean flours, Nut butters, Well-cooked lentils (pureed), Bean purees (e.g. hummus) | Whole beans and lentils |

| Grains | Ground flax or Chia Seeds (as tolerated) | Steel cut oats (well-cooked as oatmeal) | Rolled well-cooked oats | |

| Spices | Basil, Sage, Oregano, Salt, Nutmeg, Cumin, Cinnamon, Turmeric, Saffron, Mint, Bay leaves, Tamari (wheat free soy sauce), Fenugreek tea, Fennel tea, Vanilla | Dill, Thyme, Rosemary Tarragon, Cilantro, Basil, Parsley | Mint, Ginger, Garlic (minced), Paprika, Chives, Daikon, Mustard | Wasabi, Tamarind, Horseradish, Fenugreek, Fennel |

| Sweeteners | Stevia, Maple syrup, Honey (local), Unsweetened fruit juice | Lemon and lime juice | ||

| Misc. | Capsule or liquid supplements, Cocoa powder | Baking powder (no cornstarch), Baking soda, Unflavored gelatin | Ghee, Light mayonnaise, Vinegar | Ketchup (sugar free), Hot sauce (sugar free) |

Chronic inflammatory processes contribute to the pathogenesis of many age-related diseases. In search of anti-inflammatory foods, researchers in the University of Wollongong, Australia, have systematically screened 115 variety of common dietary plants and mushrooms for their anti-inflammatory activity. Gunawardena and colleagues tested 115 commercially available plants and mushroom foods (including 115 identical samples heated with glucose) for their anti-inflammatory ability 80. The plant and mushroom samples were prepared by methods usually employed with food preparation, involving heating (i.e. ‘cooking’) and mechanical dispersion. Samples were prepared by blending in a food processor with water before heating in a microwave for 10 minutes under control conditions or including 1% glucose, to enhance Maillard reaction products. Using using the free radical nitric oxide (NO) and tumour necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) as pro-inflammatory markers, 10 foods demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory activity (see Table 5) 80. The activation of macrophages leads to secretion of inflammatory molecules such as the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and the free radical nitric oxide (NO), which play an important role in inflammation and nitroxidative stress in many age-related diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease 81.

Table 5. Anti-inflammatory foods

Seven of these food preparations, including lime zest, English breakfast tea, honey brown mushroom, button mushroom, oyster mushroom, cinnamon and cloves demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory activity with IC 50 values between 0.1 and 0.5 mg/ml. However, the most active food samples were onion, followed by oregano and red sweet potato exhibiting IC 50 values below 0.1 mg/ml. In addition, English breakfast tea leaves, oyster mushroom, onion, cinnamon and button mushroom preparations suppressed TNF-α production, exhibiting with IC 50 values below 0.5 mg/ml in RAW 264.7 macrophages 6.

Secondary screen using RAW 264.7 macrophages, NO and TNF-α as pro-inflammatory markers, of the 10 products, oyster mushroom and cinnamon, demonstrated the most significant anti-inflammatory activities (with IC 50 values below 0.1 mg/ml), followed by cloves, oregano, onion, English breakfast tea leaves and lime zest (see Table 2) 6. The commonly used drug for the management of inflammatory conditions are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which have several adverse effects especially gastric irritation leading to the formation of gastric ulcers 82. Two anti-inflammatory drugs, including prednisone and the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) ibuprofen were also tested in the same study assay systems. Ibuprofen was toxic to cells at concentrations of 1.63 ± 0.44 mM, and NO and TNF-α production were down-regulated at the same concentrations (Table 6). Prednisone inhibited LPS + IFN-γ induced NO and TNF-α production with IC 50 values of 0.25 ± 0.09 mg/ml (Table 6).

Table 6. Anti-inflammatory foods re-tested in macrophages

Onions have been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, e.g. downregulation of adipokine expression in the visceral adipose tissue of rats or attenuation of vascular inflammation and oxidative stress in fructose-fed rats 83, 84. Among the polyphenols in onions, quercetin was suggested to be the responsible anti-inflammatory ingredient, as evidenced by the downregulation of COX2 transcription in human lymphocytes 85. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory activity of the onion has been

studied also in relation to the presence of thiosulfinates and cepaenes 86, 87.

Anti-inflammatory properties of cinnamon has been demonstrated for Cinnamomum osmophloem kaneh 88, 89, but less is known about the ‘true’ cinnamon of India, Cinnamomum zeylanicum. Some authors reported significant inhibitory effects of inflammatory signalling by the extracts of C. cassia 90. Sodium benzoate appears to be one of the active ingredients in cinnamon, since it inhibits LPS-induced expression of inducible NO synthase (iNOS), pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1 β) and surface markers for inflammatory activation such as CD11b, CD11c, and CD68 in mouse microglia 91. However, E-cinnamaldehyde and o-methoxycinnamaldehyde are responsible for most of the anti-inflammatory activity of cinnamon 92.

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) extracts have been identified as having potent free radical (including superoxide anion) scavenging properties, and metal chelating activities, which may be due to the presence of flavonoids. Cloves contain considerable concentrations of eugenol, beta-caryophyllene, quercetin and kaempferol as well as rhamnetin and kaempferol and their glycosides 93.

Red sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), a species rich in β-carotene and anthocyanins 94, has been demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory properties for the first time by this study 6.

Lime (Citrus aurantifolia) rich in flavonol glycosides, especially of kaempferol-type are known for their anti-oxidant properties 95, this study 6 is also the first to report on its anti-inflammatory activities.

A handful studies have shown the anti-inflammatory properties of the various mushroom species. For example, oyster mushroom concentrate was shown to suppress LPS-induced secretion of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-12p40 in RAW264.7 macrophages and also suppressed PGE2 and NO by down-regulation of COX-2 and iNOS expression, respectively. Oyster mushroom concentrate also inhibited LPS-dependent DNA binding activity of AP-1 and NF-κ B in RAW264.7 cells 96. In mushrooms, water-soluble polysaccharides, especially the β-glucans, are most likely to be the substances responsible for the anti-inflammatory properties. For example, β-glucans isolated Pleurotus ostreatus were able to potentiate the anti-inflammatory effects of methotrexate in rat models of experimental arthritis or colitis 97, 98. A further potential anti-inflammatory compound in mushrooms could be ergothioneine, a sulfur containing amino acid that functions as an antioxidant and is present in mushrooms at a concentration of up to 2.0mg/g 99. In Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), ergothioneine given intravenously 1h before or 18 h after cytokine (IL-1 and IFN-γ) insufflation, decreased lung injury and lung inflammation in cytokine insufflated rats 100.

The anti-inflammatory activity in these food samples survived ‘cooking’ and suggesting these foods may be useful in limiting inflammation in a variety of age-related inflammatory diseases 6. Furthermore, these foods could be a source for the discovery of novel anti-inflammatory drugs 6. However, validation of these foods containing anti-inflammatory properties will require further clinical trials in human subjects before any recommendation can be given for their use to treat inflammatory conditions.

Inflammatory bowel disease dietary guidelines

To help patients navigate their nutritional questions, the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases recently reviewed the best current evidence to develop expert recommendations regarding dietary measures that might help to control and prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease 101. In particular, the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases focused on the dietary components and additives that they felt were the most important to consider because they comprise a large proportion of the diets that inflammatory bowel disease patients may follow. Furthermore, the recent International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases guidelines are an excellent starting point for discussions between patients and their doctors about whether specific dietary changes might be helpful in reducing symptoms and risk of relapse of inflammatory bowel disease. However, all patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should work with their doctor or a nutritionist, who will conduct a nutritional assessment to check for malnutrition and provide advice to correct deficiencies if they are present.

The International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases recommendations were developed with the aim of reducing symptoms and inflammation 101. The ways in which altering the intake of particular foods may trigger or reduce inflammation are quite diverse, and the mechanisms are better understood for certain foods than others. For example, fruits and vegetables are generally higher in fiber, which is fermented by bacterial enzymes within the colon. This fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that provide beneficial effects to the cells lining the colon. Patients with active IBD have been observed to have decreased short-chain fatty acids, so increasing the intake of plant-based fiber may work, in part, by boosting the production of short-chain fatty acids. However, it is important to note disease-specific considerations that might be relevant to your particular situation. For example, about one-third of Crohn’s disease patients will develop an area of intestinal narrowing, called a stricture, within the first 10 years of diagnosis. Insoluble fiber can worsen symptoms and, in some cases, lead to intestinal blockage if a stricture is present. So, while increasing consumption of fruits and vegetable is generally beneficial for Crohn’s disease, patients with a stricture should limit their intake of insoluble fiber.

Table 7. The International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases guidelines

| Food | If you have Crohn’s disease | If you have ulcerative colitis |

| Fruits | increase intake | insufficient evidence |

| Vegetables | increase intake | insufficient evidence |

| Red/processed meat | insufficient evidence | decrease intake |

| Unpasteurized dairy products | best to avoid | best to avoid |

| Dietary fat | decrease intake of saturated fats and avoid trans fats | decrease consumption of myristic acid (palm, coconut, dairy fat), avoid trans fats, and increase intake of omega-3 (from marine fish but not dietary supplements) |

| Food additives | decrease intake of maltodextrin-containing foods | decrease intake of maltodextrin-containing foods |

| Thickeners | decrease intake of carboxymethylcellulose | decrease intake of carboxymethylcellulose |

| Carrageenan (a thickener extracted from seaweed) | decrease intake | decrease intake |

| Titanium dioxide (a food colorant and preservative) | decrease intake | decrease intake |

| Sulfites (flavor enhancer and preservative) | decrease intake | decrease intake |

What are specific diets for inflammatory bowel disease?

A number of specific diets have been explored for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including the Mediterranean diet, specific carbohydrate diet, Crohn’s disease exclusion diet, autoimmune protocol diet, and a diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs). Although the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases group initially set out to evaluate some of these diets, they did not find enough high-quality trials that specifically studied them 101. Therefore, they limited their recommendations to individual dietary components. Stronger recommendations may be possible once additional trials of these dietary patterns become available. For the time being, patients are to monitor for correlations of specific foods to their symptoms. In some cases, patients may explore some of these specific diets to see if they help.

Anti inflammatory diet meal plan

By following the US Department of Health food guide, called ChooseMyPlate 102, you can make healthier food choices. The new US Department of Agriculture’s food guide 2015-2020 103 encourages you to eat more fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and low-fat dairy. Using the guide 103, you can learn what type of food you should eat and how much you should eat. You also learn why and how much you should exercise.

There are 5 major food groups that make up a healthy diet:

- Grains

- Vegetables

- Fruits

- Dairy

- Protein foods

You should eat foods from each group every day. How much food you should eat from each group depends on your age, gender, and how active you are.

ChooseMyPlate 102 makes specific recommendations for each type of food group.

1) GRAINS: MAKE AT LEAST HALF OF YOUR GRAINS WHOLE GRAINS

- Whole grains contain the entire grain. Processed grains have had the bran and germ removed. Be sure to read the ingredient list label and look for whole grains first on the list.

- Foods with whole grains have more fiber and protein than food made with processed grains.

- Examples of whole grains are breads and pastas made with whole-wheat flour, oatmeal, bulgur, faro, and cornmeal.

- Examples of processed grains are white flour, white bread, and white rice.

Most children and adults should eat about 5 to 8 servings of grains a day (also called “ounce equivalents”). Children age 8 and younger need about 3 to 5 servings. At least half those servings should be whole grain. An example of one serving of grains includes:

- 1 slice of bread

- Half of a bagel

- 1 cup (30 grams)of cereal

- 1/2 cup (165 grams) cooked rice

- 5 whole-wheat crackers

- 1/2 cup (75 grams) cooked pasta

Eating whole grains can help improve your health by 104:

- Reducing the risk of many chronic diseases.

- Whole grains can help you lose weight. Portion size is still key. Because whole grains have more fiber and protein, they are more filling than refined grains, so you can eat less to get the same feeling of being full. But if you replace vegetables with starches, you’ll gain weight, even if you eat whole grain.

- Whole grains can help you have regular bowel movements.

Ways to eat more whole grains:

- Eat brown rice instead of white rice.

- Use whole-grain pasta instead of regular pasta.

- Replace part of white flour with wheat flour in recipes.

- Replace white bread with whole-wheat bread.

- Use oatmeal in recipes instead of bread crumbs.

- Snack on air-popped popcorn instead of chips or cookies.

2) VEGETABLES: MAKE HALF OF YOUR PLATE FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

- Vegetables can be raw, fresh, cooked, canned, frozen, dried, or dehydrated.

- Vegetables are organized into 5 subgroups based on their nutrient content. The groups are dark-green vegetables, starchy vegetables, red and orange vegetables, beans and peas, and other vegetables.

- Try to include vegetables from each group, try to make sure you aren’t only picking options from the “starchy” group.

Most children and adults should eat between 2 and 3 cups (200 to 300 grams) of vegetables a day. Children age 8 need about 1 to 1 1/2 cups (100 to 150 grams). Examples of a cup include:

- Large ear of corn

- Three 5-inch (13 centimeters) broccoli spears

- 1 cup (100 grams) cooked vegetables

- 2 cups (250 grams) of raw, leafy greens

- 2 medium carrots

- 1 cup (240 milliliters) 100% vegetable juice (carrot, tomato)

Eating vegetables can help improve your health in the following ways:

- Lowers your risk of heart disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes

- Helps protect you against some cancers

- Helps lower blood pressure

- Reduces the risk of kidney stones

- Helps reduce bone loss

Ways to eat more vegetables:

- Keep plenty of frozen vegetables handy in your freezer.

- Buy pre-washed salad and pre-chopped veggies to cut down on prep time.

- Add veggies to soups and stews.

- Add vegetables to spaghetti sauces.

- Try veggie stir-fries.

- Eat raw carrots, broccoli, or bell pepper strips dipped in hummus or ranch dressing as a snack.

3) FRUITS: MAKE HALF OF YOUR PLATE FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

- Fruits can be fresh, canned, frozen, or dried.

Most adults need 1 1/2 to 2 cups (200 to 250 grams) of fruit a day. Children age 8 and younger need about 1 to 1 1/2 cups (120 to 200 grams). Examples of a cup include:

- 1 small piece of fruit, such as an apple or pear

- 8 large strawberries

- 1/2 cup (130 grams) dried apricots or other dried fruit

- 1 cup (240 milliliters) 100% fruit juice (orange, apple, grapefruit)

- 1 cup (100 grams) cooked or canned fruit

- 1 cup (250 grams) chopped fruit

Eating fruit can help improve your health, they may help to:

- Lower your risk of heart disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes

- Protect you against some cancers

- Lower blood pressure

- Reduce the risk of kidney stones

- Reduce bone loss

Ways to eat more fruit:

- Put out a fruit bowl and keep it full of fruit.

- Stock up on dried, frozen, or canned fruit, so you always have it available. Choose fruit that is canned in water or juice instead of syrup.

- Buy pre-cut fruit in packages to cut down on prep time.

- Try meat dishes with fruit, such as pork with apricots, lamb with figs, or chicken with mango.

- Grill peaches, apples, or other firm fruit for a healthy, tasty dessert.

- Try a smoothie made with chopped fruit and plain yogurt for breakfast.

- Use dried fruit to add texture to trail mixes.

4) PROTEIN FOODS: CHOOSE LEAN PROTEINS

Protein foods include meat, poultry, seafood, beans and peas, eggs, processed soy products, nuts and nut butters, and seeds. Beans and peas are also part of the vegetable group.

- Choose meats that are low in saturated fat and cholesterol, such as lean cuts of beef and chicken and turkey without skin.

- Most adults need 5 to 6 1/2 servings of protein a day (also called “ounce equivalents”). Children age 8 and younger need about 2 to 4 servings.

Examples of a serving include:

- 1 oz (28 grams) lean meat; like beef, pork, or lamb

- 1 oz (28 grams) poultry; such as turkey or chicken

- 1 large egg

- 1/4 cup (50 grams) tofu

- 1/2 cup (50 grams) cooked beans or lentils

- 1 tablespoon (15 grams) peanut butter

- 1/3 cup (35 grams) nuts

Eating lean protein can help improve your health:

- Seafood high in omega-3 fats, such as salmon, sardines, or trout, can help prevent heart disease.

- Peanuts and other nuts, such as almonds, walnuts, and pistachios, when eaten as part of a healthy diet, can help lower the risk of heart disease.

- Lean meats and eggs are a good source of iron

Ways to include more lean protein in your diet:

- Choose lean cuts of beef, which include sirloin, tenderloin, round, chuck, and shoulder or arm roasts and steaks.

- Choose lean pork, which include tenderloin, loin, ham, and Canadian bacon.

- Choose lean lamb, which includes tenderloin, chops, and leg.

- Buy skinless chicken or turkey, or take the skin off.

- Grill, roast, poach, or broil meats, poultry, and seafood instead of frying.

- Trim all visible fat and drain off any fat when cooking.

- Substitute peas, beans, or soy in place of meat at least once a week. Try bean chili, pea or bean soup, stir-fried tofu, rice and beans, or veggie burgers.

- Include 8 ounces (225 grams) of cooked seafood a week

5) DAIRY: CHOOSE LOW-FAT OR FAT-FREE DAIRY FOODS

Most children and adults should get about 3 cups (720 milliliters) of dairy a day. Children age 2 to 8 need about 2 to 2 1/2 cups (480 to 600 milliliters). Examples of a cup include:

- 1 cup (240 milliliters) milk

- 1 regular container of yogurt

- 1 1/2 ounces (45 grams) hard cheese (such as cheddar, mozzarella, Swiss, Parmesan)

- 1/3 cup (40 grams) shredded cheese

- 2 cups (450 grams) cottage cheese

- 1 cup (250 grams) pudding made with milk or frozen yogurt

- 1 cup (240 milliliters) calcium-fortified soymilk

Eating dairy food can improve your health:

- Consuming dairy foods is important for improving bone health especially during childhood and adolescence, when bone mass is being built.

- Dairy foods have vital nutrients including calcium, potassium, vitamin D, and protein.

- The intake of dairy products is linked to reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and lower blood pressure in adults.

- Low-fat or fat-free milk products provide little or no solid fat.

Ways to include low-fat foods from the dairy group in your diet:

- Include milk or calcium-fortified soymilk (soy beverage) as a beverage at meals. Choose fat-free or low-fat milk.

- Add fat-free or low-fat milk instead of water to oatmeal and hot cereals.

- Use fat-free or low-fat milk when making condensed cream soups (such as cream of tomato).

- Top casseroles, soups, stews, or vegetables with shredded reduced-fat or low-fat cheese.

- Use lactose-free or lower lactose products if you have trouble digesting dairy products. Also, you can get more calcium from non-dairy sources such as fortified juices, canned fish, soy foods, and green leafy vegetables.

6) OILS: EAT SMALL AMOUNTS OF HEART-HEALTHY OILS

- Oils are not a food group. However, they provide important nutrients and should be part of a healthy diet.

- Fats such as butter and shortening are solid at room temperature. They contain high levels of saturated fats or trans fats. Eating a lot of these fats can increase your risk of heart disease.

- Oils are liquid at room temperature. They contain monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. These types of fats are generally good for your heart.

- Children and adults should get about 5 to 7 teaspoons (25 to 35 milliliters) of oil a day. Children age 8 and younger need about 3 to 4 teaspoons (15 to 20 milliliters) a day.

- Choose oils such as olive, canola, sunflower, safflower, soybean, and corn oils.

- Some foods are also high in healthy oils. They include avocados, some fish, olives, and nuts.

7) WEIGHT MANAGEMENT AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

ChooseMyPlate 102 also provides information about how to lose excess weight:

- You can use the online SuperTracker to learn what you currently eat and drink. By writing down what you eat and drink every day, you can see where you can make better choices.

- You can use the Daily Food Plan to learn what to eat and drink. You just enter your height, weight, and age to get a personalized eating plan.

- Use the SuperTracker to track your daily activity and food you eat, plus your weight.

- If you have any specific health concerns, such as heart disease or diabetes, be sure to discuss any dietary changes with your doctor or registered dietitian first.

You also learn how to make better choices, such as:

- Eating the right amount of calories to keep you at a healthy weight

- Not overeating and avoiding big portions

- Eating fewer foods with empty calories. These are foods high in sugar or fat with few vitamins or minerals.

- Eating a balance of healthy foods from all 5 food groups

- Making better choices when eating out at restaurants

- Cooking at home more often, where you can control what goes into the foods you eat

- Exercising 150 minutes a week

- Decreasing your screen time in front of the TV or computer

- Getting tips for increasing your activity level

- Sears B. Toxic Fat. New York, NY, USA: Regan Books; 2008.[↩]

- Serhan CN. Resolution phase of inflammation: novel endogenous anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators and pathways. Annual Review of Immunology. 2007;25:101–137. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17090225[↩]

- Serhan CN, Brain SD, Buckley CD, et al. Resolution of inflammation: state of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2007;21(2):325-332. doi:10.1096/fj.06-7227rev. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3119634/[↩]

- Hotamisligil GS (2006) Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444, 860–867. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17167474[↩]

- Libby P (2002) Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 420, 868–874. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12490960[↩]

- Anti-inflammatory activity of cinnamon (C. zeylanicum and C. cassia) extracts – identification of E-cinnamaldehyde and o-methoxy cinnamaldehyde as the most potent bioactive compounds. Food Funct. 2015 Mar;6(3):910-9. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00680a. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25629927[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG (1995) The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 21:195-218.[↩]

- Wyss-Coray T (2006) Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med 12:1005-1015.[↩]

- Hansson GK (2005) Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 352:1685-1695.[↩]

- Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A (2005) Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7:211-217.[↩]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS (2005) Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 115:1111-1119.[↩]

- Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality Associated With the Metabolic Syndrome. Bo Isomaa, Peter Almgren, Tiinamaija Tuomi, Björn Forsén, Kaj Lahti, Michael Nissén, Marja-Riitta Taskinen, Leif Groop. Diabetes Care Apr 2001, 24 (4) 683-689; DOI: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683[↩]

- The Metabolic Syndrome as Predictor of Type 2 Diabetes. Carlos Lorenzo, Mayor Okoloise, Ken Williams, Michael P. Stern, Steven M. Haffner. Diabetes Care Nov 2003, 26 (11) 3153-3159; DOI: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3153[↩]

- Scirica BM, Morrow DA. Is C-reactive protein an innocent bystander or proatherogenic culprit? The verdict is still out. Circulation. 2006;113:2128–34, discussion 51. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/17/2128.long[↩]

- Packard RR, Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from vascular biology to biomarker discovery and risk prediction. Clin Chem. 2008;54:24–38. http://clinchem.aaccjnls.org/content/54/1/24.long[↩]

- Pradhan AD, Ridker PM. Do atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes share a common inflammatory basis? Eur Heart J. 2002;23:831–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12042000[↩]

- Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, Fischer HG, Lowel H, Doring A, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB. C-Reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation. 1999;99:237–242. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9892589[↩]

- Cummings DM, King DE, Mainous AG, Geesey ME. Combining serum biomarkers: the association of C-reactive protein, insulin sensitivity, and homocysteine with cardiovascular disease history in the general US population. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:180–185. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16575270[↩]

- Rutter MK, Meigs JB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and prediction of cardiovascular events in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2004;110:380–385. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15262834[↩]

- Ford ES, Ajani UA, Mokdad AH. The metabolic syndrome and concentrations of C-reactive protein among U.S youth. Diabetes care. 2005;28:878–881. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15793189[↩]

- Liu S, Tinker L, Song Y, Rifai N, Bonds DE, Cook NR, Heiss G, Howard BV, Hotamisligil GS, Hu FB, Kuller LH, Manson JE. A prospective study of inflammatory cytokines and diabetes mellitus in a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1676–1685. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17698692[↩]

- Sutcliffe S, Platz EA. Inflammation in the etiology of prostate cancer: an epidemiologic perspective. Urologic oncology. 2007;25:242–249. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17483023[↩]

- The effects of diet on inflammation: emphasis on the metabolic syndrome. Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Esposito K. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Aug 15; 48(4):677-85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16904534/[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Inflammation and cancer: how hot is the link ? Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Sethi G. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006 Nov 30; 72(11):1605-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16889756/[↩]

- Casas, R., Sacanella, E., & Estruch, R. (2014). The immune protective effect of the Mediterranean diet against chronic low-grade inflammatory diseases. Endocrine, metabolic & immune disorders drug targets, 14(4), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530314666140922153350[↩]

- Health effects of trans-fatty acids: experimental and observational evidence. Mozaffarian D, Aro A, Willett WC. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009 May; 63 Suppl 2():S5-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19424218/[↩]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, Food, and Inflammation: Psychoneuroimmunology and Nutrition at the Cutting Edge. Psychosomatic medicine. 2010;72(4):365-369. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dbf489. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2868080/[↩]

- Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation, 101 (2000), pp. 1767-1772.[↩]

- Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and increased risk of recurrent coronary events after myocardial infarction. Circulation, 101 (2000), pp. 2149-2153.[↩]

- Interleukin-18 is a strong predictor of cardiovascular death in stable and unstable angina. Circulation, 106 (2002), pp. 24-30.[↩]

- Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Psychosom Med. 2009 Feb; 71(2):171-86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19188531/[↩]

- The Effects of Diet on Inflammation: Emphasis on the Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Volume 48, Issue 4, 15 August 2006, Pages 677-685. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109706013350[↩]

- Schulze MB, Fung TT, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Dietary patterns and changes in body weight in women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1444-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16988088[↩]

- Newby PK, Muller D, Hallfrisch J, Andres R, Tucker KL. Food patterns measured by factor analysis and anthropometric changes in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:504-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15277177[↩]

- Schulz M, Nothlings U, Hoffmann K, Bergmann MM, Boeing H. Identification of a food pattern characterized by high-fiber and low-fat food choices associated with low prospective weight change in the EPIC-Potsdam cohort. J Nutr. 2005;135:1183-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15867301[↩]

- Newby PK, Muller D, Hallfrisch J, Qiao N, Andres R, Tucker KL. Dietary patterns and changes in body mass index and waist circumference in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1417-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12791618[↩]

- Popkin BM, Duffey KJ. Does hunger and satiety drive eating anymore? Increasing eating occasions and decreasing time between eating occasions in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1342-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20237134[↩]

- Harvard University, Harvard School of Public Health. Carbohydrates. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/carbohydrates/[↩]

- Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. Hu FB, Willett WC. JAMA. 2002 Nov 27; 288(20):2569-78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12444864/[↩]

- Diabetes Care 2008 Dec; 31(12): 2281-2283. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-1239. International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2008. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/31/12/2281.full[↩]

- Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, Giugliano G, Giugliano F, Ciotola M, Quagliaro L, Ceriello A, Giugliano D. Circulation. 2002 Oct 15; 106(16):2067-72. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/106/16/2067.long[↩]

- Mellen PB, Walsh TF, Herrington DM. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:283–90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17449231[↩]

- Priebe M, van Binsbergen J, de Vos R, Vonk RJ. Whole grain foods for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD006061. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006061.pub2.[↩]

- Pereira MA, O’Reilly E, Augustsson K, Fraser GE, Goldbourt U, Heitmann BL, Hallmans G, Knekt P, Liu S, Pietinen P, Spiegelman D, Stevens J, Virtamo J, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Dietary fiber and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:370–376. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14980987[↩]

- Liu S. Whole-grain foods, dietary fiber, and type 2 diabetes: searching for a kernel of truth. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2003;77:527–529. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/77/3/527.long[↩]

- King DE. Dietary fiber, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:594–600. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15884088[↩]

- Ajani UA, Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Dietary fiber and C-reactive protein: findings from national health and nutrition examination survey data. The Journal of nutrition. 2004;134:1181–1185. http://jn.nutrition.org/content/134/5/1181.long[↩]

- King DE, Egan BM, Geesey ME. Relation of dietary fat and fiber to elevation of C-reactive protein. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1335–1339. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14636916[↩]

- Ma Y, Griffith JA, Chasan-Taber L, et al. Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein-. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;83(4):760-766. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1456807/[↩]

- King DE, Egan BM, Woolson RF, Mainous AG, 3rd, Al-Solaiman Y, Jesri A. Effect of a high-fiber diet vs a fiber-supplemented diet on C-reactive protein level. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:502–506. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17353499[↩]

- Inflammatory disease processes and interactions with nutrition. Br J Nutr. 2009 May;101 Suppl 1:S1-45. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509377867. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19586558/[↩][↩]

- Dietary patterns and mortality in Danish men and women: a prospective observational study. British Journal of Nutrition (2001), 85, 219-225. DOI: 10.1079/BJN2000240. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/2C582B42A8FEC3F37A7EEE62875078B1/S0007114501000307a.pdf[↩][↩]

- Diets and cardiovascular disease. An evidence-based assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol, 45 (2005), pp. 1379-1387.[↩]

- The diet-heart hypothesis: a critique. J Am Coll Cardiol, 43 (2004), pp. 731-733.[↩]

- Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA, 288 (2002), pp. 2569-2578.[↩]

- Diet, nutrition, and coronary heart disease. P.S. Douglas (Ed.), Cardiovascular Health and Disease in Women (2nd edition.), WB Saunders, Philadelphia, PA (2002), pp. 71-92.[↩]

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis, an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:115-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9887164[↩]

- Brown AA, Hu FB. Dietary modulation of endothelial function: implications for cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:673-86. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/73/4/673.full[↩]

- Major dietary patterns are related to plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Fung TT, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Manson JE, Hu FB. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Oct; 80(4):1029-35. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/80/4/1029.long[↩][↩]

- In humans, serum polyunsaturated fatty acid levels predict the response of proinflammatory cytokines to psychologic stress. Maes M, Christophe A, Bosmans E, Lin A, Neels H. Biol Psychiatry. 2000 May 15; 47(10):910-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10807964/[↩]

- Habitual dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in relation to inflammatory markers among US men and women. Pischon T, Hankinson SE, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Circulation. 2003 Jul 15; 108(2):155-60. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/108/2/155.long[↩]

- Depressive symptoms, omega-6:omega-3 fatty acids, and inflammation in older adults. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Belury MA, Porter K, Beversdorf DQ, Lemeshow S, Glaser R. Psychosom Med. 2007 Apr; 69(3):217-24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2856352/[↩]

- Relationship of plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids to circulating inflammatory markers. Ferrucci L, Cherubini A, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Corsi A, Lauretani F, Martin A, Andres-Lacueva C, Senin U, Guralnik JM. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Feb; 91(2):439-46. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16234304/[↩]

- Inflammatory disease processes and interactions with nutrition. Calder PC, Albers R, Antoine JM, Blum S, Bourdet-Sicard R, Ferns GA, Folkerts G, Friedmann PS, Frost GS, Guarner F, Løvik M, Macfarlane S, Meyer PD, M’Rabet L, Serafini M, van Eden W, van Loo J, Vas Dias W, Vidry S, Winklhofer-Roob BM, Zhao J. Br J Nutr. 2009 May; 101 Suppl 1():S1-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19586558/[↩][↩]

- Effect of dietary antioxidants on postprandial endothelial dysfunction induced by a high-fat meal in healthy subjects. Esposito K, Nappo F, Giugliano F, Giugliano G, Marfella R, Giugliano D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Jan; 77(1):139-43. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/77/1/139.long[↩]

- Anti-inflammatory Diets. Journal of the American College of Nutrition Vol. 34 , Iss. sup1,2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2015.1080105[↩]

- Holub BJ. Clinical nutrition: 4. Omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular care. Hoffer LJ, Jones PJ, eds. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2002;166(5):608-615. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC99405/[↩]

- Rodriguez-Leyva D, Bassett CM, McCullough R, Pierce GN. The cardiovascular effects of flaxseed and its omega-3 fatty acid, alpha-linolenic acid. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2010;26(9):489-496. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989356/[↩]

- Diet and Inflammation. Nutrition in Clinical Practice Vol 25, Issue 6, pp. 634 – 640. First published date: December-07-2010. 10.1177/0884533610385703[↩]

- F.B. Hu. The Mediterranean Diet and mortality—olive oil and beyond. N Engl J Med, 348 (2003), pp. 2595-2596[↩]

- Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report . Nutrition Journal. 2014;13:5. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3896778/[↩][↩]

- Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Sandborn WJ, Dubois C, Rutgeerts P. Correlation between the Crohn’s disease activity and Harvey-Bradshaw indices in assessing Crohn’s disease severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20096379[↩]

- Bosscher D, Breynaert A, Pieters L, Hermans N. Food-based strategies to modulate the composition of the intestinal microbiota and their associated health effects. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 6):5–11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20224145[↩]

- Jia W, Whitehead RN, Griffiths L, et al. Is the abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii relevant to Crohn’s disease? Ross F, ed. Fems Microbiology Letters. 2010;310(2):138-144. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02057.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2962807/[↩]

- McFarland LV. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in adult patients. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG. 2010;16(18):2202-2222. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i18.2202. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2868213/[↩]

- Lorea Baroja M, Kirjavainen PV, Hekmat S, Reid G. Anti-inflammatory effects of probiotic yogurt in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;149(3):470-479. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03434.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2219330/[↩]

- Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:563–573. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21468064[↩]

- Wall R, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C. Fatty acids from fish: the anti-inflammatory potential of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutrition reviews. 2010;68:280–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00287.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20500789[↩]

- Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutrition Journal. 2014;13:5. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3896778/[↩]