What is acne Acne, pimples or zits, is a chronic inflammatory disorder of pilosebaceous (sebaceous gland a small gland in the skin which secretes a lubricating

What is antiperspirant An antiperspirant is a chemical agent that reduces perspiration or sweating. The active ingredients of roll-on, spray and powder formulations are traditionally

Tips for raising children Being a parent can be great fun, with lots of opportunities for love and excitement. It also brings challenges and hard

How to deal with a difficult child Becoming a parent is one of the biggest role you’ll ever take on. It’s one of the few

What is loneliness Loneliness or being lonely is about not feeling connected to others. You can feel lonely in a room full of people. The

How to fix a broken relationship with your girlfriend or boyfriend A relationship can start with you feeling on top of the world, but it

How to deal with a broken heart A broken heart, relationship breakup and divorce are among the toughest life experiences people can face at any

How to deal with divorce as a man or a woman Divorce and separation are among the toughest life experiences people can face. Men and

What to do after a breakup A romantic relationship breakup, separation and divorce are one of the most stressful and emotional experiences in life. People

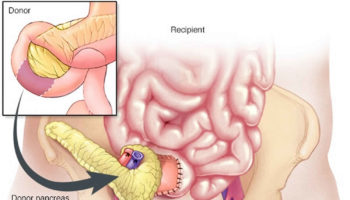

Can you get a pancreas transplant? Yes. More than 50,000 pancreas transplant have been performed worldwide (> 29,000 from the United States and >19,000 from