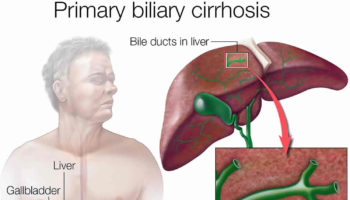

What is primary biliary cholangitis Primary biliary cholangitis or PBC is used to be called primary biliary cirrhosis, is a chronic progressive autoimmune liver disease in which the

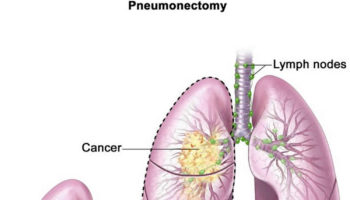

What is pneumonectomy Pneumonectomy is a surgery to remove an entire lung. Pneumonectomy is most commonly performed for a primary lung cancer. The lung is

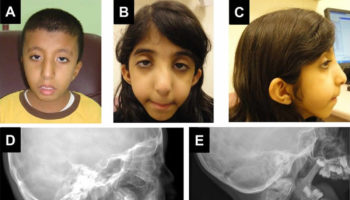

What is Klippel Feil syndrome Klippel Feil syndrome is a rare congenital (present at birth) bone disorder characterized by the fusion of two or more

What is Kleine Levin syndrome Kleine Levin syndrome is a rare and complex neurological disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of excessive sleep (hypersomnia), excessive food

What is homocystinuria Homocystinuria is an inherited disorder in which the body is unable to process certain building blocks of proteins (amino acids) properly ((Sacharow

What is Kallmann syndrome Kallmann syndrome combines an impaired sense of smell with a hormonal disorder, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, that delays or prevents puberty. The hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

What is imperforate anus Imperforate anus is also called anal atresia, is a birth defect (congenital) where the opening to the anus is missing or blocked.

What is chelation therapy Chelation therapy is a treatment that involves administering a drug called a chelator, which has a magnetically charged pocket that can

What is water therapy Water therapy is also called hydrotherapy, aquatic therapy, pool therapy or balneotherapy, is the external or internal use of water in

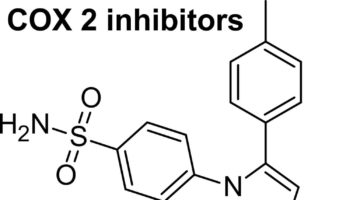

What is a COX-2 inhibitor COX-2 inhibitor is short for cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor, is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is the competitive inhibitor of