Articulation disorder

Articulation disorder is when a child has trouble pronouncing certain words, making him or her difficult to be understood. Word sounds may be dropped, added, distorted, or swapped. Keep in mind that some sound changes may be part of an accent and are not speech errors. Articulation disorders involve a wide range of errors children can make when talking.

Signs of an articulation disorder can include:

- Leaving off sounds from words (example: saying “coo” instead of “school”)

- Adding sounds to words (example: saying “puhlay” instead of “play” or “pinanio” for “piano”)

- Distorting sounds in words (example: saying “thith” instead of “this”)

- Swapping sounds in words (example: saying “wadio” instead of “radio”)

- Substituting a “w” for an “r” (“wabbit” for “rabbit”)

- Omitting sounds (“cool” for “school”).

Phonologic process means patterns of sounds made when your child pronounces certain consonants or vowels. Phonological disorder is a pattern of sound mistakes, such as not pronouncing certain letters.

A child with an articulation disorder has problems forming speech sounds properly. A child with a phonological disorder can produce the sounds correctly, but may use them in the wrong place.

When young children are growing, they develop speech sounds in a predictable order. It is normal for young children to make speech errors as their language develops; however, children with an articulation or phonological disorder will be difficult to understand when other children their age are already speaking clearly.

Articulation or phonological difficulties are generally not a direct result of brain injury. Children with an acquired brain injury may have different difficulties with their speech patterns. These are generally caused by dyspraxia or dysarthria. Some children with acquired brain injuries may also have difficulties with literacy and language.

A qualified speech pathologist should assess your child if there are any concerns about the quality of the sounds they make, the way they talk, or their ability to be understood.

It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological errors or to differentially diagnose these two separate disorders. A single child might show both error types, and those specific errors might need different treatment approaches.

A speech-language pathologist can test your child’s speech. The speech-language pathologist will listen to your child to hear how he says sounds. The speech-language pathologist also will look at how your child moves his lips, jaw, and tongue. The speech-language pathologist may also test your child’s language skills. Many children with speech sound disorders also have language disorders. For example, your child may have trouble following directions or telling stories.

It is important to have your child’s hearing checked to make sure he does not have a hearing loss. A child with a hearing loss may have more trouble learning to talk.

The speech-language pathologist can also help decide if you have a speech problem or speak with an accent. An accent is the unique way that groups of people sound. Accents are NOT a speech or language disorder.

The speech-language pathologist can recommend a therapy plan to help your child overcome his or her disorder. Speech-language pathologists work with children to help them:

- Recognize and correct sounds that they are making wrong

- Learn how to correctly form their problem sound

- Practice saying certain words and making certain sounds

The speech-language pathologist can also give you activities and strategies to help your child practice at home.

If your child has a physical defect in the mouth, the pathologist can also refer your child to an ear, nose, throat doctor or orthodontist if needed.

Articulation disorder key points to remember:

- Articulation and phonology refer to the making of speech sounds.

- Children with phonological disorders or phonemic awareness disorders may have ongoing problems with language and literacy.

- If there are any concerns about your child’s speech, ask your family doctor to arrange an assessment with a qualified speech pathologist.

- With appropriate speech therapy, many children with articulation or phonological disorders will have a big improvement in their speech.

If you or anyone else in regular contact with your child, such as their teacher have any concerns about your child’s speech, ask your family doctor or pediatrician to arrange an assessment with a speech pathologist. You can also arrange to see a speech pathologist directly; however, the fees may be higher.

Articulation and phonological disorders signs and symptoms

Articulation disorders

Articulation refers to making sounds. The production of sounds involves the coordinated movements of the lips, tongue, teeth, palate (top of the mouth) and respiratory system (lungs). There are also many different nerves and muscles used for speech.

If your child has an articulation disorder, they:

- have problems making sounds and forming particular speech sounds properly (e.g. they may lisp, so that s sounds like th)

- may not be able to produce a particular sound (e.g. they can’t make the r sound, and say ‘wabbit’ instead of ‘rabbit’).

Phonological disorders

Phonology refers to a regular pattern in which sounds are put together to make words or word speech mistakes. The mistakes may be common in young children learning speech skills, but when they persist past a certain age, it may be a disorder. Signs of a phonological process disorder can include:

If your child has a phonological disorder, they:

- Are able to make the sounds correctly, but they may use it in the wrong position in a word, or in the wrong word, e.g. a child may use the d sound instead of the g sound, and so they say ‘doe’ instead of ‘go’

- Make mistakes with the particular sounds in words, e.g. they can say k in ‘kite’ but with certain words, will leave it out e.g. ‘lie’ instead of ‘like’.

- Say only one syllable in a word (example: “bay” instead of “baby”).

- Simplify a word by repeating two syllables (example: “baba” instead of “bottle”).

- Leave out a consonant sound (example: “at” or “ba” instead of “bat”).

- Change certain consonant sounds (example: “tat” instead of “cat”)

Phonological disorders and phonemic awareness disorders (the understanding of sounds and sound rules in words) have been linked to ongoing problems with language and literacy. It is therefore important to make sure that your child gets the most appropriate treatment.

It can be much more difficult to understand children with phonological disorders compared to children with pure articulation disorders. Children with phonological disorders often have problems with many different sounds, not just one.

Speech sound disorder

Speech sound disorders is an umbrella term referring to any difficulty or combination of difficulties with perception, motor production, or phonological representation of speech sounds and speech segments—including phonotactic rules governing permissible speech sound sequences in a language.

As young children learn language skills, it’s normal for them to have some difficulty saying words correctly. That’s part of the learning process. Their speech skills develop over time. They master certain sounds and words at each age. By age 8, most children have learned how to master all word sounds.

But some children have speech sound disorders. This means they have trouble saying certain sounds and words past the expected age. This can make it hard to understand what a child is trying to say. Speech sound disorders include articulation disorder and phonological process disorder.

The table below shows the ages when most English-speaking children develop sounds. Children learning more than one language may develop some sounds earlier or later.

| By 3 months | Makes cooing sounds |

| By 5 months | Laughs and makes playful sounds |

| By 6 months | Makes speech-like babbling sounds like puh, ba, mi, da |

| By 1 year | Babbles longer strings of sounds like mimi, upup, bababa |

| By 3 years | Says m, n, h, w, p, b, t, d, k, g, and f in words Familiar people understand the child’s speech |

| By 4 years | Says y and v in words May still make mistakes on the s, sh, ch, j, ng, th, z, l, and r sounds Most people understand the child’s speech |

Some children have speech problems because the brain has trouble sending messages to the speech muscles telling them how and when to move. This is called apraxia. Childhood apraxia of speech is not common but will cause speech problems.

Some children have speech problems because the muscles needed to make speech sounds are weak. This is called dysarthria.

Your child may have speech problems if he has:

- a developmental disorder, like autism;

- a genetic syndrome, like Down syndrome;

- hearing loss, from ear infections or other causes; or

- brain damage, like cerebral palsy or a head injury.

Adults can also have speech sound disorders. Some adults have problems that started when they were children. Others may develop speech problems after a stroke or traumatic brain injury, or other trauma.

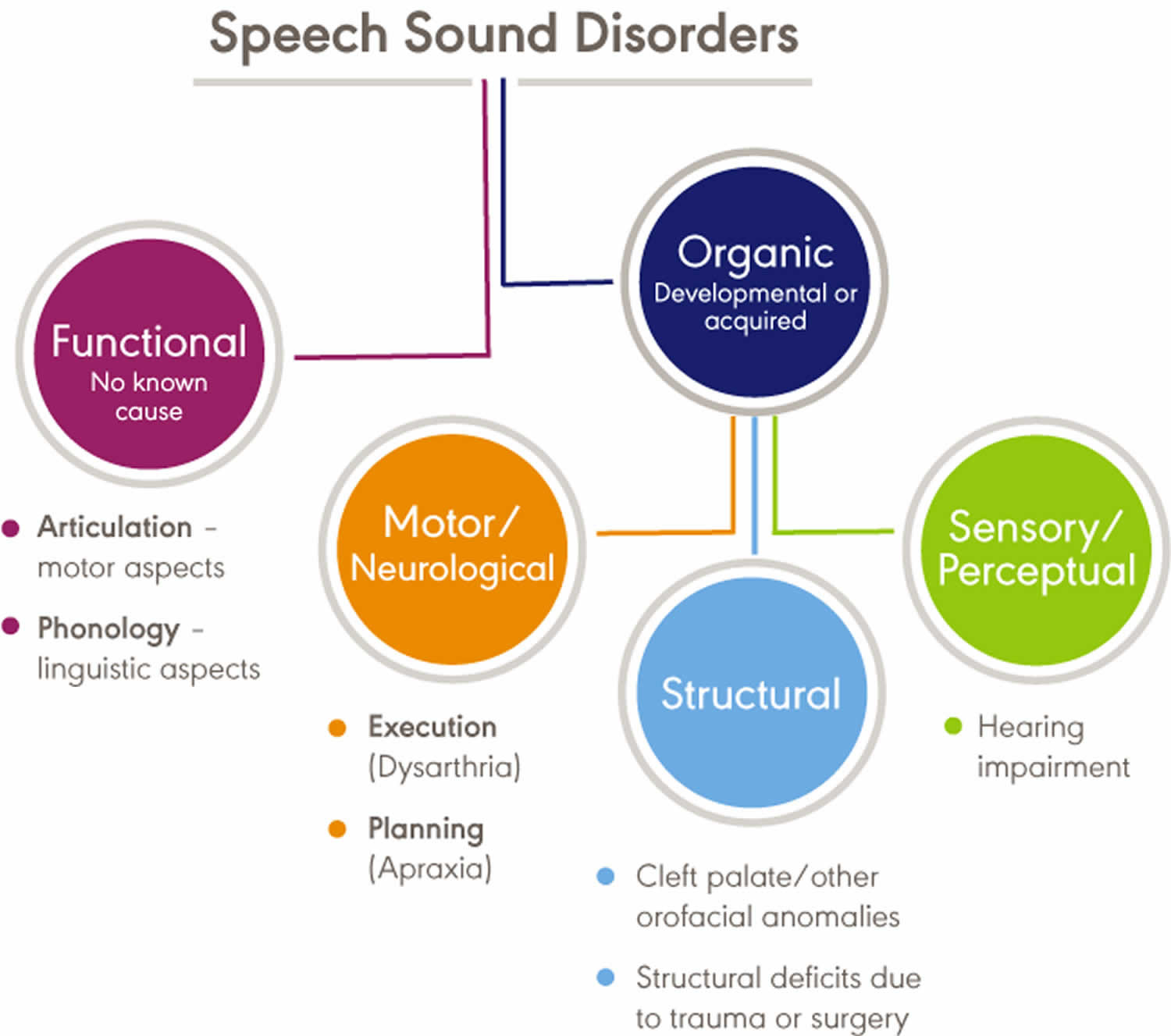

Speech sound disorders can be organic or functional in nature. Organic speech sound disorders result from an underlying motor/neurological, structural, or sensory/perceptual cause. Functional speech sound disorders are idiopathic—they have no known cause. See figure 1 below.

Speech-language pathologists play a central role in the screening, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of persons with speech sound disorders.

Figure 1. Speech sound disorder

Organic speech sound disorders

Organic speech sound disorders include those resulting from motor/neurological disorders (e.g., childhood apraxia of speech and dysarthria), structural abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip/palate and other structural deficits or anomalies), and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing impairment).

Functional speech sound disorders

Functional speech sound disorders include those related to the motor production of speech sounds and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production. Historically, these disorders are referred to as articulation disorders and phonological disorders, respectively. Articulation disorders focus on errors (e.g., distortions and substitutions) in production of individual speech sounds. Phonological disorders focus on predictable, rule-based errors (e.g., fronting, stopping, and final consonant deletion) that affect more than one sound. It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological disorders; therefore, many researchers and clinicians prefer to use the broader term, “speech sound disorder,” when referring to speech errors of unknown cause.

How common is speech sound disorders?

The incidence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of new cases identified in a specified period. The prevalence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of children who are living with speech problems in a given time period.

Estimated prevalence rates of speech sound disorders vary greatly due to the inconsistent classifications of the disorders and the variance of ages studied. The following data reflect the variability:

- Overall, 2.3% to 24.6% of school-aged children were estimated to have speech delay or speech sound disorders 1.

- A 2012 survey from the National Center for Health Statistics estimated that, among children with a communication disorder, 48.1% of 3- to 10-year old children and 24.4% of 11- to 17-year old children had speech sound problems only. Parents reported that 67.6% of children with speech problems received speech intervention services 2.

- Residual or persistent speech errors were estimated to occur in 1% to 2% of older children and adults 3.

- Reports estimated that speech sound disorders are more prevalent in boys than in girls, with a ratio ranging from 1.5:1.0 to 1.8:1.0 4.

- Prevalence rates were estimated to be 5.3% in African American children and 3.8% in White children 5.

- Reports estimated that 11% to 40% of children with speech sound disorders had concomitant language impairment 6.

- Poor speech sound production skills in kindergarten children have been associated with lower literacy outcomes 7. Estimates reported a greater likelihood of reading disorders (relative risk: 2.5) in children with a preschool history of speech sound disorders 8.

Speech sound disorders causes

Often, there is no known cause for a speech sound disorder. But some speech sound errors may be caused by:

- Injury to the brain

- Intellectual or developmental disability

- Problems with hearing or hearing loss, such as a history of ear infections

- Physical abnormalities that affect speech, including cleft palate or cleft lip

- Disorders affecting the nerves involved in speech.

Frequently reported risk factors for functional speech sound disorders include the following:

- Gender—the incidence of speech sound disorders is higher in males than in females 9.

- Pre- and perinatal problems—factors such as maternal stress or infections during pregnancy, complications during delivery, preterm delivery, and low birthweight were found to be associated with delay in speech sound acquisition and with speech sound disorders 10.

- Family history—children who have family members (parents or siblings) with speech and/or language difficulties were more likely to have a speech disorder 11.

- Persistent otitis media with effusion—persistent otitis media with effusion (often associated with hearing loss) has been associated with impaired speech development 12.

Speech sound disorders signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of functional speech sound disorders include the following:

- omissions/deletions —certain sounds are omitted or deleted (e.g., “cu” for “cup” and “poon” for “spoon”)

- substitutions —one or more sounds are substituted, which may result in loss of phonemic contrast (e.g., “thing” for “sing” and “wabbit” for “rabbit”)

- additions —one or more extra sounds are added or inserted into a word (e.g., “buhlack” for “black”)

- distortions —sounds are altered or changed (e.g., a lateral “s”)

- syllable-level errors —weak syllables are deleted (e.g., “tephone” for “telephone”)

Signs and symptoms may occur as independent articulation errors or as phonological rule-based error patterns. In addition to these common rule-based error patterns, idiosyncratic error patterns can also occur. For example, a child might substitute many sounds with a favorite or default sound, resulting in a considerable number of homonyms (e.g., shore, sore, chore, and tore might all be pronounced as door).

Influence of accent

An accent is the unique way that speech is pronounced by a group of people speaking the same language and is a natural part of spoken language. Accents may be regional; for example, someone from New York may sound different than someone from South Carolina. Foreign accents occur when a set of phonetic traits of one language are carried over when a person learns a new language. The first language acquired by a bilingual or multilingual individual can influence the pronunciation of speech sounds and the acquisition of phonotactic rules in subsequently acquired languages. No accent is “better” than another. Accents, like dialects, are not speech or language disorders but, rather, only reflect differences.

Influence of dialect

Not all sound substitutions and omissions are speech errors. Instead, they may be related to a feature of a speaker’s dialect (a rule-governed language system that reflects the regional and social background of its speakers). Dialectal variations of a language may cross all linguistic parameters, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. An example of a dialectal variation in phonology occurs with speakers of African American English when a “d” sound is used for a “th” sound (e.g., “dis” for “this”). This variation is not evidence of a speech sound disorder but, rather, one of the phonological features of African American English.

Speech-language pathologists must distinguish between dialectal differences and communicative disorders and must:

- recognize all dialects as being rule-governed linguistic systems;

- understand the rules and linguistic features of dialects represented by their clientele; and

- be familiar with nondiscriminatory testing and dynamic assessment procedures, such as identifying potential sources of test bias, administering and scoring standardized tests using alternative methods, and analyzing test results in light of existing information regarding dialect use.

Speech sound disorders diagnosis

First, your child’s hearing should be checked. This is to make sure that he or she isn’t simply hearing words and sounds incorrectly.

If hearing loss is ruled out, you may want to contact a speech-language pathologist. This is a speech expert who evaluates and treats children who are having problems with speech-language and communication.

By watching and listening to a child speak, the speech-language pathologist can determine whether the issues are part of normal growth and development or are a speech sound disorder. The speech-language pathologist will evaluate your child’s speech and language skills, keeping in mind accents and dialect. Speech-language pathologists can also assess if a physical problem in the mouth is affecting your child’s ability to speak.

Speech sound disorder treatment

Speech-language pathologists can help you or your child say sounds correctly and clearly. Treatment may include the following:

- Learning the correct way to make sounds

- Learning to tell when sounds are right or wrong

- Practicing sounds in different words

- Practicing sounds in longer sentences

Historically, treatments that focus on motor production of speech sounds are called articulation approaches; treatments that focus on the linguistic aspects of speech production are called phonological/language-based approaches.

Articulation approaches target each sound deviation and are often selected by the clinician when the child’s errors are assumed to be motor based; the aim is correct production of the target sound(s).

Phonological/language-based approaches target a group of sounds with similar error patterns, although the actual treatment of exemplars of the error pattern may target individual sounds. Phonological approaches are often selected in an effort to help the child internalize phonological rules and generalize these rules to other sounds within the pattern (e.g., final consonant deletion, cluster reduction).

Articulation and phonological/language-based approaches might both be used in therapy with the same individual at different times or for different reasons.

Both approaches for the treatment of speech sound disorders typically involve the following sequence of steps:

- Establishment—eliciting target sounds and stabilizing production on a voluntary level.

- Generalization—facilitating carry-over of sound productions at increasingly challenging levels (e.g., syllables, words, phrases/sentences, conversational speaking).

- Maintenance—stabilizing target sound production and making it more automatic; encouraging self-monitoring of speech and self-correction of errors.

Approaches for selecting initial therapy targets for children with articulation and/or phonological disorders include the following:

- Developmental—target sounds are selected on the basis of order of acquisition in typically developing children.

- Non-developmental/theoretically motivated, including the following:

- Complexity—focuses on more complex, linguistically marked phonological elements not in the child’s phonological system to encourage cascading, generalized learning of sounds 13.

- Dynamic systems—focuses on teaching and stabilizing simple target phonemes that do not introduce new feature contrasts in the child’s phonological system to assist in the acquisition of target sounds and more complex targets and features 14.

- Systemic—focuses on the function of the sound in the child’s phonological organization to achieve maximum phonological reorganization with the least amount of intervention. Target selection is based on a distance metric. Targets can be maximally distinct from the child’s error in terms of place, voice, and manner and can also be maximally different in terms of manner, place of production, and voicing.

- Client-specific—selects targets based on factors such as relevance to the child and his or her family (e.g., sound is in child’s name), stimulability, and/or visibility when produced (e.g., /f/ vs. /k/).

- Degree of deviance and impact on intelligibility—selects targets on the basis of errors (e.g., errors of omission; error patterns such as initial consonant deletion) that most effect intelligibility.

The following are brief descriptions of both general and specific treatments for children with speech sound disorders. These approaches can be used to treat speech sound problems in a variety of populations.

Treatment selection will depend on a number of factors, including the child’s age, the type of speech sound errors, the severity of the disorder, and the degree to which the disorder affects overall intelligibility 15.

Contextual utilization approaches

Contextual utilization approaches recognize that speech sounds are produced in syllable-based contexts in connected speech and that some (phonemic/phonetic) contexts can facilitate correct production of a particular sound.

Contextual utilization approaches may be helpful for children who use a sound inconsistently and need a method to facilitate consistent production of that sound in other contexts. Instruction for a particular sound is initiated in the syllable context(s) where the sound can be produced correctly. The syllable is used as the building block for practice at more complex levels.

For example, production of a “t” may be facilitated in the context of a high front vowel, as in “tea”. Facilitative contexts or “likely best bets” for production can be identified for voiced, velar, alveolar, and nasal consonants. For example, a “best bet” for nasal consonants is before a low vowel, as in “mad”.

Phonological contrast approaches

Phonological contrast approaches are frequently used to address phonological error patterns. They focus on improving phonemic contrasts in the child’s speech by emphasizing sound contrasts necessary to differentiate one word from another. Contrast approaches use contrasting word pairs as targets instead of individual sounds.

There are four different contrastive approaches—minimal oppositions, maximal oppositions, treatment of the empty set, and multiple oppositions.

- Minimal Oppositions (also known as “minimal pairs” therapy)—uses pairs of words that differ by only one phoneme or single feature signaling a change in meaning. Minimal pairs are used to help establish contrasts not present in the child’s phonological system (e.g., “door” vs. “sore,” “pot” vs. “spot,” “key” vs. “tea”).

- Maximal Oppositions—uses pairs of words containing a contrastive sound that is maximally distinct and varies on multiple dimensions (e.g., voice, place, and manner) to teach an unknown sound. For example, “mall” and “call” are maximal pairs because /m/ and /k/ vary on more than one dimension—/m/ is a bilabial voiced nasal, whereas /k/ is a velar voiceless stop.

- Treatment of the Empty Set—similar to the maximal oppositions approach but uses pairs of words containing two maximally opposing sounds (e.g., /r/ and /d/) that are unknown to the child (e.g., “row” vs. “doe” or “ray” vs. “day”).

- Multiple Oppositions—a variation of the minimal oppositions approach but uses pairs of words contrasting a child’s error sound with three or four strategically selected sounds that reflect both maximal classification and maximal distinction (e.g., “door,” “four,” “chore,” and “store,” to reduce backing of /d/ to /g/).

Complexity approach

The complexity approach is a speech production approach based on data supporting the view that the use of more complex linguistic stimuli helps promote generalization to untreated but related targets.

The complexity approach grew primarily from the maximal oppositions approach. However, it differs from the maximal oppositions approach in a number of ways. Rather than selecting targets on the basis of features such as voice, place, and manner, the complexity of targets is determined in other ways. These include hierarchies of complexity (e.g., clusters, fricatives, and affricates are more complex than other sound classes) and stimulability (i.e., sounds with the lowest levels of stimulability are most complex). In addition, although the maximal oppositions approach trains targets in contrasting word pairs, the complexity approach does not.

A core vocabulary approach focuses on whole-word production and is used for children with inconsistent speech sound production who may be resistant to more traditional therapy approaches.

Words selected for practice are those used frequently in the child’s functional communication. A list of frequently used words is developed (e.g., based on observation, parent report, and/or teacher report), and a number of words from this list are selected each week for treatment. The child is taught his or her “best” word production, and the words are practiced until consistently produced.

Cycles approach

The cycles approach targets phonological pattern errors and is designed for children with highly unintelligible speech who have extensive omissions, some substitutions, and a restricted use of consonants.

Treatment is scheduled in cycles ranging from 5 to 16 weeks. During each cycle, one or more phonological patterns are targeted. After each cycle has been completed, another cycle begins, targeting one or more different phonological patterns. Recycling of phonological patterns continues until the targeted patterns are present in the child’s spontaneous speech.

The goal is to approximate the gradual typical phonological development process. There is no predetermined level of mastery of phonemes or phoneme patterns within each cycle; cycles are used to stimulate the emergence of a specific sound or pattern—not to produce mastery of it.

Distinctive feature therapy

Distinctive feature therapy focuses on elements of phonemes that are lacking in a child’s repertoire (e.g., frication, nasality, voicing, and place of articulation) and is typically used for children who primarily substitute one sound for another.

Distinctive feature therapy uses targets (e.g., minimal pairs) that compare the phonetic elements/features of the target sound with those of its substitution or some other sound contrast. Patterns of features can be identified and targeted; producing one target sound often generalizes to other sounds that share the targeted feature.

Metaphon therapy

Metaphon therapy is designed to teach metaphonological awareness—that is, the awareness of the phonological structure of language. This approach assumes that children with phonological disorders have failed to acquire the rules of the phonological system.

The focus is on sound properties that need to be contrasted. For example, for problems with voicing, the concept of “noisy” (voiced) versus “quiet” (voiceless) is taught. Targets typically include processes that affect intelligibility, can be imitated, or are not seen in typically developing children of the same age.

Naturalistic speech intelligibility intervention

Naturalist speech intelligibility intervention addresses the targeted sound in naturalistic activities that provide the child with frequent opportunities for the sound to occur. For example, using a McDonald’s menu, signs at the grocery store, or favorite books, the child can be asked questions about words that contain the targeted sound(s). The child’s error productions are recast without the use of imitative prompts or direct motor training. This approach is used with children who are able to use the recasts effectively.

Nonspeech oral–motor therapy

Nonspeech oral–motor therapy involves the use of oral-motor training prior to teaching sounds or as a supplement to speech sound instruction. The rationale behind this approach is that (a) immature or deficient oral-motor control or strength may be causing poor articulation and (b) it is necessary to teach control of the articulators before working on correct production of sounds. Consult systematic reviews of this treatment to help guide clinical decision making.

Speech sound perception training

Speech sound perception training is used to help a child acquire a stable perceptual representation for the target phoneme or phonological structure. The goal is to ensure that the child is attending to the appropriate acoustic cues and weighting them according to a language-specific strategy (i.e., one that ensures reliable perception of the target in a variety of listening contexts).

Recommended procedures include (a) auditory bombardment in which many and varied target exemplars are presented to the child, sometimes in a meaningful context such as a story and often with amplification, and (b) identification tasks in which the child identifies correct and incorrect versions of the target (e.g., “rat” is a correct exemplar of the word corresponding to a rodent, whereas “wat” is not).

Tasks typically progress from the child judging speech produced by others to the child judging the accuracy of his or her own speech. Speech sound perception training is often used before and/or in conjunction with speech production training approaches.

Traditionally, the speech stimuli used in these tasks are presented via live voice by the speech-language pathologist. More recently, computer technology has been used—an advantage of this approach is that it allows for the presentation of more varied stimuli representing, for example, multiple voices and a range of error types.

Children with persisting speech difficulties

Speech difficulties sometimes persist throughout the school years and into adulthood. Pascoe et al. 16 define persisting speech difficulties as “difficulties in the normal development of speech that do not resolve as the child matures or even after they receive specific help for these problems”. The population of children with persistent speech difficulties is heterogeneous, varying in cause, severity, and nature of speech difficulties 17.

A child with persisting speech difficulties (functional speech sound disorders) may be at risk for:

- difficulty communicating effectively when speaking;

- difficulty acquiring reading and writing skills; and

- psychosocial problems (e.g., low self-esteem, increased risk of bullying).

Intervention approaches vary and may depend on the child’s area(s) of difficulty (e.g., spoken language, written language, and/or psychosocial issues).

In designing an effective treatment protocol, the speech-language pathologist considers:

- teaching and encouraging the use of self-monitoring strategies to facilitate consistent use of learned skills;

- collaborating with teachers and other school personnel to support the child and to facilitate his or her access to the academic curriculum; and

- managing psychosocial factors, including self-esteem issues and bullying 16.

Transition planning

Children with persisting speech difficulties may continue to have problems with oral communication, reading and writing, and social aspects of life as they transition to post-secondary education and vocational settings. The potential impact of persisting speech difficulties highlights the need for continued support to facilitate a successful transition to young adulthood. These supports include the following:

- Transition Planning—the development of a formal transition plan in middle or high school that includes discussion of the need for continued therapy, if appropriate, and supports that might be needed in postsecondary educational and/or vocational settings.

- Disability Support Services—individualized support for postsecondary students that may include extended time for tests, accommodations for oral speaking assignments, the use of assistive technology (e.g., to help with reading and writing tasks), and the use of methods and devices to augment oral communication, if necessary.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 provide protections for students with disabilities who are transitioning to postsecondary education. The protections provided by these acts (a) ensure that programs are accessible to these students and (b) provide aids and services necessary for effective communication (U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2011).

- Wren Y, Miller LL, Peters TJ, Emond A, Roulstone S. Prevalence and Predictors of Persistent Speech Sound Disorder at Eight Years Old: Findings From a Population Cohort Study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2016;59(4):647–673. doi:10.1044/2015_JSLHR-S-14-0282 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5280061[↩]

- Black, L.I., Vahratian, A., & Hoffman, H.J. (2015). Communication disorders and use of intervention services among children aged 3–17 years: United States, 2012. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.[↩]

- Flipsen P Jr. Emergence and Prevalence of Persistent and Residual Speech Errors. Semin Speech Lang. 2015;36(4):217–223. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1562905[↩]

- Wren, Y., Miller, L.L., Peters, T.J., Emond, A., & Roulstone, S. (2016). Prevalence and predictors of persistent speech sound disorder at eight years old: Findings from a population cohort study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59, 647–673. doi:10.1044/2015_JSLHR-S-14-0282[↩]

- Shriberg, L.D., Tomblin, J.B., & McSweeny, J.L. (1999). Prevalence of speech delay in 6-year-old children and comorbidity with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1461–1481. doi:10.1044/jslhr.4206.1461[↩]

- Eadie P., Morgan A., Ukoumunne O. C., Ttofari Eecen K., Wake M., & Reilly S. (2015). Speech sound disorder at 4 years: Prevalence, comorbidities, and predictors in a community cohort of children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57, 578–584.[↩]

- Preliteracy Speech Sound ProductionSkill and Later Literacy Outcomes:A Study Using the Templin Archive. LANGUAGE, SPEECH, AND HEARING SERVICES IN SCHOOLS, Vol. 43,97–115; January 2012 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ann_Smit/publication/51769782_Preliteracy_Speech_Sound_Production_Skill_and_Later_Literacy_Outcomes_A_Study_Using_the_Templin_Archive/links/554a4ad30cf21ed21358e225.pdf[↩]

- Peterson, R., Pennington, B., Shriberg, L., & Boada, R.(2009).What influences literacy outcome in children with speech sounddisorders?Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research,52,1175–1188.[↩]

- Shriberg L. D., Tomblin J. B., & McSweeny J. L. (1999). Prevalence of speech delay in 6-year-old children and comorbidity with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42, 1461–1481.[↩]

- Fox A. V., Dodd B., & Howard D. (2002). Risk factors for speech disorders in children. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 37, 117–131.[↩]

- Campbell T. F., Dollaghan C. A., Rockette H. E., Paradise J. L., Feldman H. M., Shriberg L. D., … Kurs-Lasky M. (2003). Risk factors for speech delay of unknown origin in 3-year-old children. Child Development, 74, 346–357.[↩]

- Fox, A.V., Dodd, B. and Howard, D. (2002), Risk factors for speech disorders in children. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 37: 117-131. doi:10.1080/13682820110116776[↩]

- Storkel HL. The Complexity Approach to Phonological Treatment: How to Select Treatment Targets. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2018;49(3):463–481. doi:10.1044/2017_LSHSS-17-0082[↩]

- Clinical Implications of Dynamic Systems Theory for Phonological Development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology vol 19, 1, Feb 2010 https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2009/08-0047[↩]

- Williams, L. A., McLeod, S., & McCauley, R. J. (2010). Introduction to interventions for speech sound disorders in children. In R. J. M. R. J. J McCauley (Ed.), Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (1 ed., pp. 1-26). Paul H. Brookes Publishing. [↩]

- Pascoe M, Stackhouse J, and Wells B (2006) Persisting speech difficulties in children. Chichester: Wiley.[↩][↩]

- Wren Y. E., Roulstone S. E., & Miller L. L. (2012). Distinguishing groups of children with persistent speech disorder: Findings from a prospective population study. Logopedics, Phoniatrics and Vocology, 37(1), 1–10.[↩]