What is asthenia

Asthenia means weakness, lack of energy and strength. The term asthenia comes from the Greek (centsqsneia: privation, without; esthénos: vigor, force), it means absence of strength, vigor or force 1. Asthenia is a symptom, difficult to define, with a set of vague sensations, different for each patient. The chronic fatigue represents up to 10% of these cases, and the 0.2-0.7% belongs to the chronic fatigue syndrome. It is very important to differentiate asthenia from weakness, dizziness or difficulty breathing (dyspnea), since patients may confuse them. The factor time in asthenia is very useful for its characterization, it was defined to the prolonged fatigue when it lasts for more than a month and chronic when the duration is greater than 6 months. Depression is the commonest fatigue cause, representing approximately half of the cases.

Patients may describe asthenia as feeling 2:

- Fatigue.

- Tired.

- Weak.

- Exhausted.

- Lazy.

- Weary.

- Worn-out.

- Heavy.

- Slow.

- Like they do not have any energy or any get-up-and-go.

Health professionals have included fatigue within concepts such as:

- Asthenia.

- Lassitude.

- Malaise.

- Prostration.

- Exercise intolerance.

- Lack of energy.

- Weakness.

Men and women differ in the way they describe asthenia: men typically say they feel tired, whereas women say they feel depressed or anxious 3.

Everyone feels tired and lack of energy now and then. Sometimes you may just want to stay in bed. But, after a good night’s sleep, most people feel refreshed and ready to face a new day. If you continue to feel lack of energy for weeks, it’s time to see your doctor. He or she may be able to help you find out what’s causing your asthenia and recommend ways to relieve it.

Asthenia itself is not a disease. No cause can be identified in one third of cases of asthenia. Overexertion, deconditioning, viral illness, upper respiratory tract infection, anemia, lung disease, medications, cancer, and depression are common causes. Medical problems, treatments, and personal habits can add to asthenia. These include

- Taking certain medicines, such as antidepressants, antihistamines, and medicines for nausea and pain

- Having medical treatments, like chemotherapy and radiation

- Recovering from major surgery

- Anxiety, stress, or depression

- Staying up too late

- Drinking too much alcohol or too many caffeinated drinks

- Pregnancy

One disorder that causes extreme fatigue is chronic fatigue syndrome. This fatigue is not the kind of tired feeling that goes away after you rest. Instead, it lasts a long time and limits your ability to do ordinary daily activities.

The most effective treatment of the asthenia is to solve the underlying cause, although up to 20% of the patients remain without diagnosis. The diagnosis of the chronic fatigue syndrome is of exclusion and the criteria of the international consensus of year 1994 are due to use.

See your doctor if asthenia is making it difficult or impossible for you to manage basic tasks. See your doctor right away if you feel any of these things:

- Dizzy

- Confused

- Unable to get out of bed for 24 hours

- Lose your sense of balance

- Have trouble catching your breath

Asthenia causes

Asthenia may be classified as secondary, physiologic, or chronic. Secondary asthenia is caused by an underlying medical condition and may last one month or longer, but it generally lasts less than six months. Physiologic asthenia is an imbalance in the routines of exercise, sleep, diet, or other activity that is not caused by an underlying medical condition and is relieved with rest. Chronic asthenia lasts longer than six months and is not relieved with rest 4. Chronic fatigue syndrome is a disease that causes you to become so fatigued (tired) you can’t perform normal daily tasks. The main symptom of chronic fatigue syndrome is chronic fatigue that lasts more than 6 months. Physical or mental activities often make the symptoms worse. Rest usually doesn’t improve the symptoms.

Asthenia could be caused by one or more factors:

- Anemia. Reduced red blood cells that carry oxygen from your heart to the rest of your body.

- Poor nutrition.

- Emotional stress. Feeling anxious, depressed, or distressed can drain your energy and motivation. It is possible for asthenia and depression to coexist.

- Psychological: depression, anxiety, somatization disorder, dysthymic disorder

- Medication use (e.g., sedative-hypnotics, analgesics, antihypertensives, antidepressants, muscle relaxants, opioids, antibiotics) or substance abuse

- Sleep problems. Pain and distress can make it hard to get truly rested.

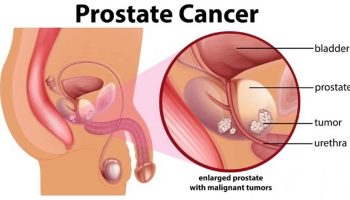

- Cancer treatment.

- Cachexia/anorexia.

- Endocrine: diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, pituitary insufficiency, hypercalcemia, adrenal insufficiency, chronic kidney disease, hepatic failure

- Metabolic disturbances.

- Hormone deficiency or excess.

- Psychological distress.

- Physical deconditioning.

- Disturbed sleep: sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, allergic or vasomotor rhinitis

- Excessive inactivity.

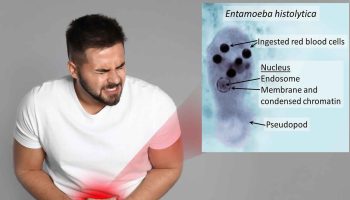

- Infectious: endocarditis, tuberculosis, mononucleosis, hepatitis, parasitic disease, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus

- Inflammatory: rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Pulmonary impairment.

- Neuromuscular dysfunction.

- Pain and other symptoms.

- Proinflammatory cytokines.

- Nutritional deficiencies.

- Dehydration.

- Infection.

- Concomitant medical illness.

- Cardiac impairment: congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, atypical angina

Having cancer can also drain your energy:

- Some cancers release proteins called cytokines that can make you feel fatigued.

- Some tumors can change the way your body uses energy and leave you feeling tired.

Many cancer treatments cause asthenia as a side effect:

- Chemotherapy. You may feel most worn out for a few days after each chemo treatment. Your asthenia may get worse with each treatment. For some people, asthenia is worst about halfway through the full course of chemo.

- Radiation. Asthenia often gets more intense with each radiation treatment until about halfway through the cycle. Then it often levels off and stays about the same until the end of treatment.

- Surgery. Asthenia is common when recovering from any surgery. Having surgery along with other cancer treatments can make asthenia last longer.

- Biologic therapy. Treatments that use vaccines or bacteria to trigger your immune system to fight cancer can cause fatigue.

Physiologic fatigue

Physiologic fatigue is initiated by inadequate rest, physical effort, or mental strain unrelated to an underlying medical condition. Diminished motivation and boredom also play a role. Physiologic fatigue is most common in adolescents and older persons. In the United States, 24 percent of adults report having fatigue lasting two weeks or longer, and two thirds of these persons cannot identify the cause of their fatigue 5.

During intense training, well-conditioned athletes occasionally misinterpret fatigue as illness or depression 6. Conversely, fatigue and depression can emerge in a physically fit athlete after as little as one week with no exercise. Submaximal exercise mitigates these symptoms when training is limited because of injury 7.

Asthenia symptoms

Asthenia means weakness, lack of energy and strength. Asthenia is a symptom, difficult to define, with a set of vague sensations, different for each patient. The chronic fatigue represents up to 10% of these cases, and the 0.2-0.7% belongs to the chronic fatigue syndrome 1.

People who have chronic fatigue syndrome may experience the following symptoms:

- Fatigue.

- Headaches.

- Sore throat.

- Tender or painful areas in your neck or armpits due to swollen lymph nodes (or lymph glands).

- Muscle soreness.

- Pain that moves from joint to joint without swelling or redness.

- Loss of memory or concentration.

- Trouble sleeping.

- Extreme tiredness after exercising that lasts more than 24 hours.

These and other symptoms often won’t go away or keep coming back for 6 months or more.

Chronic fatigue syndrome may occur after an illness (such as a cold). Or it can start during or shortly after a period of high stress. It can also come on slowly without any clear starting point or any obvious cause. In some cases,chronic fatigue syndrome can last for years.

Asthenia diagnosis

Laboratory studies should be considered, although their results affect management in only 5 percent of patients 8. Many physicians order a complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), chemistry panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, and urinalysis 9. Women of childbearing age should receive a pregnancy test. No other tests have been shown to be useful unless the history or physical examination suggests a specific medical condition 10.

Asthenia treatment

Asthenia treatment focuses on treating the underlying causes that may be contributing to asthenia.

Patients who believe that their symptoms are related to modifiable factors (e.g., workload, stress, coping strategies, depression, over commitment) are much more likely to recover than those who believe that their symptoms are due to external factors, such as a viral infection 11. In a British study, 90 percent of patients who saw their doctors for chronic fatigue received medication, diagnostic testing, or referral 12. The patients, however, were seeking to engage the physician, convey their suffering, and receive reassurance; the patients reported greatest satisfaction with physician explanations linking physical and psychological factors to psychosocial management.

Adequate sleep (i.e., generally seven to eight hours per night for adults) decreases tension and improves mood 13. Patients should be instructed to restructure their daily activities to get the sleep they need, and to practice good sleep hygiene. Recommendations for good sleep hygiene include the following: maintaining a regular morning rising time; increasing activity level in the afternoon; avoiding exercise in the evening or before bedtime; increasing daytime exposure to bright light; taking a hot bath within the two hours before bedtime; avoiding caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and excessive food or fluid intake in the evening; using the bedroom only for sleep and sex; and practicing a bedtime routine that includes minimizing light and noise exposure and turning off the television 14. Naps may help, but should be limited to less than one hour in the early afternoon. One study showed that when hospitals provided patient coverage for medical intern naps (averaging 40 minutes) during overnight shifts, the interns achieved morning fatigue scores equivalent to those who were not on call 15. Time off from work also minimizes fatigue and decreases stress 16.

Eat well. Make safe nutrition a priority. If you have lost your appetite, eat foods high in calories and protein to keep your energy up.

- Eat small meals throughout the day instead of 2 or 3 big meals

- Drink smoothies and vegetable juice for healthy calories

- Eat olive oil and canola oil with pasta, bread, or in salad dressing

- Drink water between meals to stay hydrated. Aim for 6 to 8 glasses a day

Stay active. Sitting still for too long can make fatigue worse. Some light activity can get your circulation going. You should not exercise to the point of feeling more tired while you are being treated for cancer. But, taking a daily walk with as many breaks as you need can help boost your energy and sleep better. Meta-analyses confirm the effectiveness of regular structured exercise. Physical fitness also improves energy levels. One study showed that truck drivers who engaged in 30-minute exercise sessions more than once a week had fewer traffic incidents 17. Performing some form of daily exercise, sustaining interpersonal relationships, and returning to work are consistently associated with improvement in asthenia of any cause 18. Regular moderate aerobic activity (i.e., 30 minutes of walking or an equivalent activity on most days of the week) reduces disease-related asthenia more effectively than rest. Yoga, group therapy, and stress management diminish asthenia in patients with cancer 19. Four weeks of aerobic, strength, or flexibility training is associated with improved energy and decreased fatigue 20 and moderate aerobic exercise (e.g., a daily 30-minute walk) has a more consistently positive impact on fatigue than any other intervention studied 21. Another study showed that 10 weeks of supervised exercise increased energy levels among persons with fatigue, regardless of the underlying cause 22. With the exception of patients with depression, pharmacologic therapy (including stimulants) only has a short-term impact 23. Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is effective 24.

Medications that may be causing asthenia should be replaced or discontinued, if possible, and physiologic parameters should be corrected. With cancer, renal disease, or other chronic diseases associated with anemia, patients are likely to be less fatigued if their hemoglobin level is maintained at 10 g per dL (100 g per L), using erythropoietin agents if needed 25. Nonanemic, menstruating women who have low normal ferritin levels report modest increased energy after four weeks of iron supplementation 26.

Patients who have features suggestive of depression may be offered a six-week trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) 27. Psychostimulants (e.g., methylphenidate [Ritalin], modafinil [Provigil]) improve fatigue in the short-term in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), multiple sclerosis (MS), or cancer 28. Stimulants seldom return patients to predisease performance, and the drugs are associated with headaches, restlessness, insomnia, and dry mouth 29. If used, stimulants are best used as needed for episodic situations requiring alertness.

Stimulants improve short-term performance. A randomized, double-blind, crossover study of persons driving in nighttime conditions showed that participants had fewer errors after consuming regular coffee (i.e., 200 mg of caffeine) or taking a 30-minute nap 30. Modafinil, which is approved to manage fatigue that is induced by shift work, has the same effect on performance as 600 mg of caffeine. Modafinil and caffeine do not have most of the adverse cardiovascular effects and abuse potential that are associated with amphetamines 30. Although modafinil and caffeine temporarily improve performance, they are not a substitute for adequate rest, and long-term use of modafinil has been associated with depression.

A six-week trial of an selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (e.g., fluoxetine [Prozac], paroxetine [Paxil], sertraline [Zoloft]) may be considered in patients with chronic fatigue if depression is possible 31. If the patient has difficulty getting restful sleep, trazodone (Desyrel, brand no longer available in the United States), doxepin, or imipramine (Tofranil) may be effective 32. If pain is present, the patient may respond to venlafaxine (Effexor), desipramine (Norpramin), nortriptyline (Pamelor), duloxetine (Cymbalta), or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

- [The chronic asthenia syndrome: a clinical approach]. Medicina (B Aires). 2010;70(3):284-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20529781/[↩][↩]

- Barsevick AM, Whitmer K, Walker L: In their own words: using the common sense model to analyze patient descriptions of cancer-related fatigue. Oncol Nurs Forum 28 (9): 1363-9, 2001[↩]

- Fahlén G, Knutsson A, Peter R, et al. Effort-reward imbalance, sleep disturbances and fatigue. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006;79(5):371–378.[↩]

- Brown RF, Schutte NS. Direct and indirect relationships between emotional intelligence and subjective fatigue in university students. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):585–593.[↩]

- Smith L, Tanigawa T, Takahashi M, et al. Shiftwork locus of control, situational and behavioural effects on sleepiness and fatigue in shiftworkers. Ind Health. 2005;43(1):151–170.[↩]

- Rietjens GJ, Kuipers H, Adam JJ, et al. Physiological, biochemical and psychological markers of strenuous training-induced fatigue. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26(1):16–26.[↩]

- Berlin AA, Kop WJ, Deuster PA. Depressive mood symptoms and fatigue after exercise withdrawal: the potential role of decreased fitness. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):224–230.[↩]

- Lane TJ, Matthews DA, Manu P. The low yield of physical examinations and laboratory investigations of patients with chronic fatigue. Am J Med Sci. 1990;299(5):313–318[↩]

- Fatigue: An Overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Nov 15;78(10):1173-1179. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/1115/p1173.html[↩]

- Lane TJ, Matthews DA, Manu P. The low yield of physical examinations and laboratory investigations of patients with chronic fatigue. Am J Med Sci. 1990;299(5):313–318.[↩]

- Sharpe M. Psychiatric management of PVFS. Br Med Bull. 1991;47(4):989–1005.[↩]

- Dowrick CF, Ring A, Humphris GM, Salmon P. Normalisation of unexplained symptoms by general practitioners: a functional typology. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(500):165–170[↩]

- Pilcher JJ, Ginter DR, Sadowsky B. Sleep quality versus sleep quantity: relationships between sleep and measures of health, well-being and sleepiness in college students. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(6):583–596.[↩]

- Alam T, Alessi CA. Sleep disorders. In: Rosenthal TC, Williams ME, Naughton BJ, eds. Office Care Geriatrics. Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:254–265[↩]

- Arora V, Dunphy C, Chang VY, Ahmad F, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer D. The effects of on-duty napping on intern sleep time and fatigue. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(11):792–798.[↩]

- Sonnentag S, Zijlstra FR. Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(2):330–350.[↩]

- Taylor AH, Dorn L. Stress, fatigue, health, and risk of road traffic accidents among professional drivers: the contribution of physical inactivity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:371–391.[↩]

- van Weert E, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Otter R, Postema K, Sanderman R, van der Schans C. Cancer-related fatigue: predictors and effects of rehabilitation. Oncologist. 2006;11(2):184–196[↩]

- Mock V. Evidence-based treatment for cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):112–118.[↩]

- Puetz TW, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. Effects of chronic exercise on feelings of energy and fatigue: a quantitative synthesis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):866–876[↩]

- Powell P, Bentall RP, Nye FJ, Edwards RH. Randomised controlled trial of patient education to encourage graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):387–390.[↩]

- O’Connor PJ, Puetz TW. Chronic physical activity and feelings of energy and fatigue. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(2):299–305.[↩]

- Blockmans D, Persoons P, Van Houdenhove B, Bobbaers H. Does methylphenidate reduce the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome? Am J Med. 2006;119(2):167.e23–30.[↩]

- Whiting P, Bagnall AM, Sowden AJ, Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Ramírez G. Interventions for the treatment and management of chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review [published correction appears in JAMA. 2002;287(11):1401]. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1360–1368[↩]

- Munch TN, Zhang T, Willey J, Palmer JL, Bruera E. The association between anemia and fatigue in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(6):1144–1149.[↩]

- Verdon F, Burnand B, Stubi CL, et al. Iron supplementation for unexplained fatigue in non-anaemic women: double blind randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326(7399):1124[↩]

- Greco T, Eckert G, Kroenke K. The outcome of physical symptoms with treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(8):813–818.[↩]

- Bruera E, Valero V, Driver L, et al. Patient-controlled methylphenidate for cancer fatigue: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):2073–2078[↩]

- Reineke-Bracke H, Radbruch L, Elsner F. Treatment of fatigue: modafinil, methylphenidate, and goals of care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1210–1214.[↩]

- Guilleminault C, Ramar K. Naps and drugs to combat fatigue and sleepiness. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(11):856–857.[↩][↩]

- Stulemeijer M, de Jong LW, Fiselier TJ, Hoogveld SW, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial [published correction appears in BMJ. 2005;330(7495):820]. BMJ. 2005;330(7481):14.[↩]

- Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(6):478–489.[↩]