Bacterial conjunctivitis

Bacterial conjunctivitis is conjunctivitis caused by bacteria and is very contagious. The most common bacteria are Staphylococcus species, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis 1, 2. Bacterial conjunctivitis presents with conjunctival injection, mucopurulent discharge, and crusty eyelids. The diagnosis is usually clinical. The condition is often self-limiting, but there is good evidence that antibiotics improve remission rates. Most of the current evidence suggests that the choice of topical antibiotics and the treatment regimen do not significantly affect the rate of recovery from infection. Failure to recognize and treat bacterial conjunctivitis may lead to complications, such as keratitis or anterior uveitis. Bacterial conjunctivitis is commonly associated with hyperacute (<24 hours) onset of severe and very rapid progressing conjunctivitis. Bacteria rank second among the most common causes of infectious conjunctivitis. Bacterial conjunctivitis almost always affects both eyes, although it may start in just one eye. Symptoms include gritty feeling like sand in your eye and a thick yellow discharge (pus) that crust over your eyelashes, especially after sleep. With bacterial conjunctivitis, you have sore, red eyes with a lot of sticky pus in the eye. Some bacterial infections, however, may cause little or no discharge. Sometimes the bacteria that cause pink eye are the same that cause strep throat.

Bacterial conjunctivitis has an incubation period and communicability of 1-7 days and is commonly caused by 3:

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Neisseria meningitidis

Bacterial conjunctivitis with acute or subacute onset (hours-days) of moderate to severe severity are commonly caused by 3:

- Haemophilus influenzae biotype III (previously known as Haemophilus aegyptius)

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Streptococcus viridans

- Staphylococcus aureus

Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis is used to describe any conjunctivitis lasting more than 4 weeks. It has an incubation period of 2-7 days 4.

Clinically distinguishing bacterial conjunctivitis from other conjunctivitis is essential as it can help direct therapies and potentially curb unnecessary empiric antibiotic administration. Traditionally, a purulent or mucopurulent discharge has been associated with the diagnosis of bacterial conjunctivitis while watery discharge has been more consistent with viral or allergic conjunctivitis 5. A 2003 study contested this assertion based on a lack of evidence to support discharge characteristics correlating with the cause of conjunctivitis 5, 6. A later study by the same authors concluded that three findings were significantly predictive of bacterial conjunctivitis, including glued eyes, lack of itching, and no previous history of conjunctivitis 5, 6. A 2006 prospective study of children with conjunctivitis described five clinical history and physical examination variables associated with bacterial culture-positive infections. These included a history of gluey or sticky eyelids in the morning, examination findings of mucoid or purulent discharge, eyelids or eyelashes crusting or gluing on examination, absence of burning sensation, and lack of watery discharge 7. The inconsistencies of these findings concerning discharge as a predictor of bacterial infection might be attributable to the 2003 survey focusing on history, while the 2006 study included in-office physical examination findings. These differences reinforce the idea of variability in the presentation of bacterial conjunctivitis.

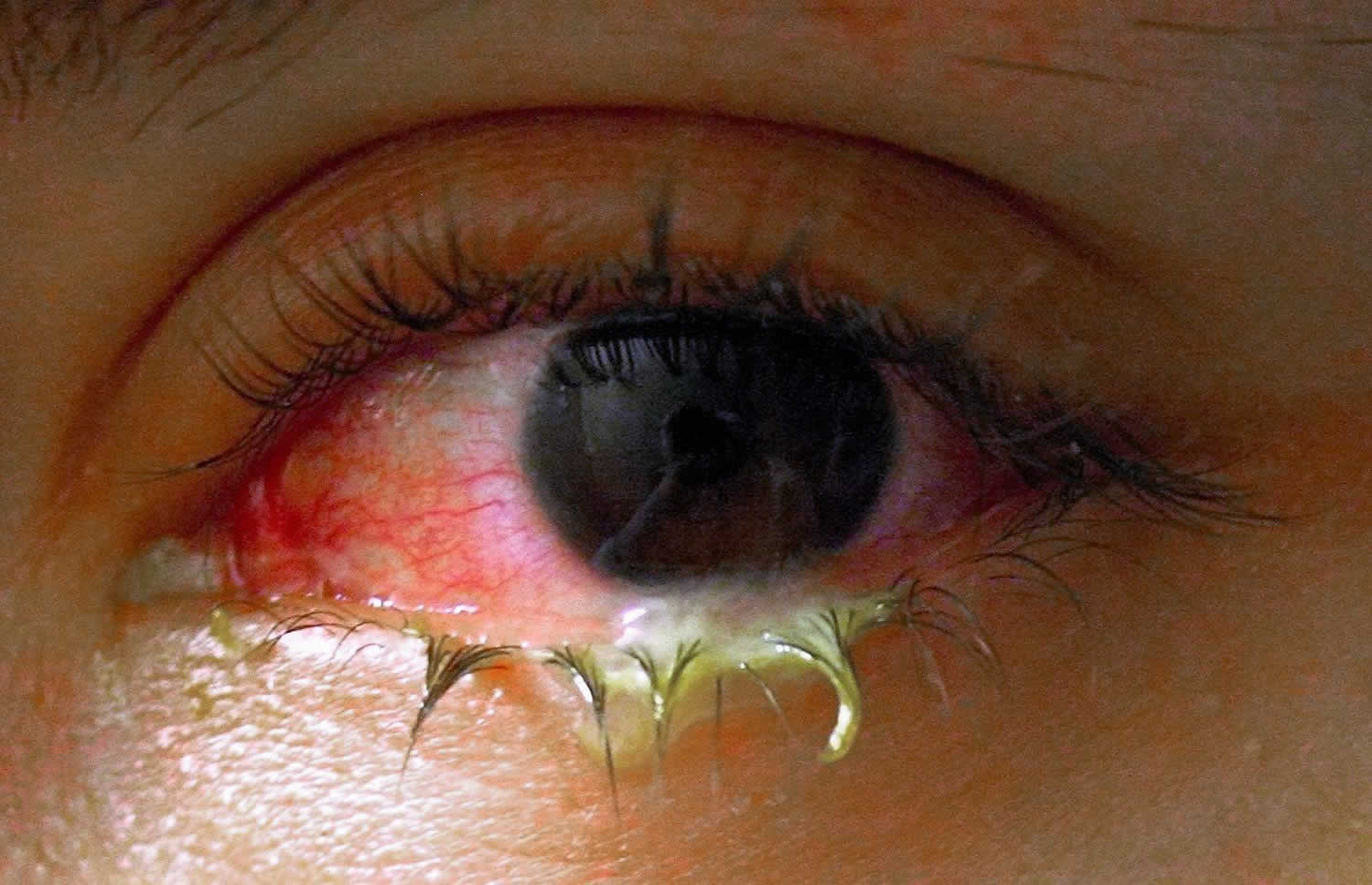

Gonococcal infection of the eye, when it does occur, typically presents as conjunctivitis (Figure 2). Gonococcal conjunctivitis in adults most often results from the accidental transfer of microorganisms from one part of the body to another (autoinoculation) in persons with genital gonococcal infection. Persons with gonococcal conjunctivitis may initially develop mild, nonpurulent conjunctivitis, that, if untreated, typically progresses to marked conjunctival redness, copious purulent discharge, and conjunctival edema 8. Less often, ulcerative keratitis develops. Untreated gonococcal conjunctivitis can cause complications that may include corneal perforation, endophthalmitis (an infection of the tissues or fluids inside the eyeball) and blindness.

Bacterial conjunctivitis may need antibiotic ointment or drops prescribed by a doctor. Treatment should be applied to both eyes, even if only one eye appears to be infected. Always treat the unaffected eye first. The findings of 2023 Cochrane review suggest that the use of topical antibiotics is associated with a modestly improved chance of resolution in comparison to the use of placebo 9. Since no evidence of serious side effects was reported, use of antibiotics may therefore be considered to achieve better clinical and microbiologic efficacy than placebo.

Figure 1. Bacterial conjunctivitis

Footnotes: Bacterial conjunctivitis symptoms include redness of the eye, swelling of the eyelids and a gunky sticky yellow discharge.

Figure 2. Gonococcal conjunctivitis

Footnote: Severe case of gonococcal conjunctivitis. Note the purulent material on the upper and lower lids.

[Source 10 ]Figure 3. Chlamydial conjunctivitis

Footnotes: 22-year-old man presenting with a long-standing (>4 months) history of redness in his right eye accompanied by scant mucopurulent discharge was treated by several courses of topically administered antibiotics. Owing to the poor response to therapy, he was referred to our ocular inflammatory clinic. External examination of the right eye revealed prominent conjunctival follicles almost exclusively located at the inferior fornix of the conjunctiva (A) and prominent conjunctival bulbar follicles at the semilunar fold (B). The rest of the examination was unremarkable except for a symptom of mild burning on urination for the past 3 months. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) on a conjunctival swab confirmed the presence of Chlamydia trachomatis in both samples and excluded the presence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The patient was prescribed a 1-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day (because topical antibiotics are ineffective). Symptoms and signs resolved completely within 1-month thereafter.

[Source 11 ]Bacterial conjunctivitis causes

Bacterial conjunctivitis is inflammation of the conjunctiva caused by direct contact with infected secretions.

The most common bacteria that cause bacterial conjunctivitis are 2:

- Staphylococcus, the same family of bacteria that cause staph infections.

- Streptococcus, the bacteria family that causes strep throat and pneumococcal disease.

- Haemophilus influenzae, a bacteria family best known for causing meningitis in young children.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), like Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea) and Treponema pallidum (syphilis). When these infections pass from birthing parent to child during birth, it can lead to neonatal conjunctivitis, a condition that can cause permanent eye damage and blindness.

Bacterial pathogens in adults are more often staphylococcal species with Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae responsible for a smaller percentage of cases 12. Staphylococcus aureus is more commonly found in adults and the elderly but is also present in pediatric cases of bacterial conjunctivitis 7. There has also been an increase in the frequency of conjunctivitis secondary to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) 12. Contact lens wearers are more susceptible to gram-negative infections 7. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is more likely to be the isolate from critically ill, hospitalized patients 7. Neonates can be affected by the vertical, oculogenital transmission of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis resulting in acute bacterial conjunctivitis 13. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis organisms can also cause a hyperacute infection in sexually active adolescents and adults 13.

The most common causative organism of bacterial conjunctivitis in children is Haemophilus influenzae, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis 14, 15, 16.

Bacterial conjunctivitis can be quite contagious. The most common ways to get the contagious bacterial conjunctivitis include:

- Direct contact with an infected person’s bodily fluids, usually through hand-to-eye contact.

- Contact with contaminated fingers, fomites or oculo-genital contact with someone infected. Young, sexually active adults below the age of 25 years, have a high risk, especially if they do not use condoms on sexual encounters.

- Spread of the infection from bacteria living in the person’s own nose and sinuses.

- Not cleaning contact lenses properly. Using poorly fitting contact lenses or decorative contacts are risks as well.

- Compromised tear production or drainage

- Disruption of the natural epithelial barrier

- Abnormality of adnexal structures

- Trauma

- Immunosuppressed status.

Children are the people most likely to get pink eye from bacteria or viruses. This is because they are in close contact with so many others in school or day care centers. Also, they don’t practice good hygiene.

In children, the disease is often caused by Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis.

The most common pathogens for bacterial conjunctivitis in adults are Staphylococcal species, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.

The course of bacterial conjunctivitis usually lasts 7-10 days.

- Hyperacute bacterial conjunctivitis is often caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. When the infection does not respond to standard antibiotic therapy in sexually active patients, Chlamydia trachomatis should be suspected.

- Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis is commonly caused Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxella lacunata, and enteric bacteria.

Bacterial conjunctivitis signs and symptoms

Bacterial conjunctivitis symptoms may include:

- the feeling that something is in your eye, or a gritty sensation in your eye

- red eyes

- burning eyes

- itchy eyes

- painful eyes (this is usually with the bacterial form)

- watery eyes

- puffy eyelids

- blurry or hazy vision

- sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- lots of mucus, pus, or thick yellow discharge from your eye. There can be so much that your eyelashes stick together.

Bacterial conjunctivitis complications

Complications from bacterial conjunctivitis are uncommon; however, severe infections can result in keratitis, corneal ulceration and perforation, and blindness 5, 7, 15.

Bacterial conjunctivitis diagnosis

In most cases, your doctor can diagnose bacterial conjunctivitis by asking about your recent health history and symptoms and examining your eyes.

Classic physical examination findings of bacterial conjunctivitis are conjunctival erythema and purulent discharge 13. A complete eye examination should include assessment of visual acuity and corneal involvement 5, 17. Although slit lamps are beneficial to a comprehensive eye assessment, they are not routinely available in primary care offices 5. An otoscopic examination is warranted if ear symptoms are reported in children to diagnose concurrent acute otitis media 15.

Rarely, your doctor may take a swab to test for sample of the liquid that drains from your eye for laboratory analysis, called a culture 2. A culture may be needed if your symptoms are severe or if your doctor suspects a high-risk cause, such as:

- A foreign body in your eye.

- A serious bacterial infection.

- A sexually transmitted infection (STI).

Conjunctival cultures are also the recommended in cases where newborn conjunctivitis (ophthalmia neonatorum) is suspected, or where copious purulent discharge makes the diagnosis of gonococcal or chlamydial infection more likely 13, 5.

Your doctor can use the results to guide your treatment.

In the following days or weeks, your doctor may recommend that you have a follow-up visit with an eye care specialist to check on how your eye is healing and adjust your treatment if necessary.

Bacterial conjunctivitis differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for bacterial conjunctivitis includes viral and allergic conjunctivitis 7. Clear discharge and itching are more characteristic of allergies and viral infections 5, 7. Trauma can also present with similar symptoms to conjunctivitis of bacterial origin. Keratitis and iridocyclitis should be ruled out as corneal infections, and iris inflammation can lead to significant morbidity 7.

Bacterial conjunctivitis treatment

Bacterial conjunctivitis can resolve without treatment; however, your doctor may prescribe antibiotic eye drops, depending on how severe your symptoms are and with the consideration of benefits of treatment, the natural course of the disease if left untreated, antibiotic resistance, and the philosophy of antibiotic stewardship 2. And distinguishing bacterial conjunctivitis from other causes of conjunctivitis can be difficult, and doctors often err on the side of empiric antibiotic therapy 17. And antibiotic eye drops or ointments may speed up your recovery.

Studies have indicated that around 50 percent of pediatric infectious conjunctivitis presentations are attributed to bacteria, while physicians prescribe antibiotics in up to 80 to 95 percent of these cases 17, 18. Ophthalmologists use antibiotic therapy in a smaller percentage of cases than general practitioners 17, 18. Treatment with topical antibiotics has demonstrated a decrease in symptoms, improved resolution times, decreased transmission, and hastened return to school or work 5, 15, 16, 17.

Conjunctivitis usually goes away on its own within 1 to 2 weeks. If your symptoms last longer than that, you should see your ophthalmologist. He or she can make sure you don’t have a more serious eye problem.

The natural course of untreated bacterial conjunctivitis is the resolution of the infection within one week 7. Another consideration is the continued resistance patterns of the eye bacterial pathogens 15. With an understanding of the described management variables, uncomplicated bacterial conjunctivitis can be treated empirically with topical antibiotics, or managed expectantly without antibiotics 5. In complicated cases involving patients with immunocompromise, contact lens use, and suspected gonococcal or chlamydial infections, antibiotic therapy should be provided 5. If the decision is made to initiate empiric treatment, the antibiotic chosen should be broad-spectrum and include coverage of gram-positive and gram-negative ocular bacteria 15. Topical aminoglycosides, polymyxin B combination drugs, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones are the most commonly prescribed ophthalmic agents 19, 15, 5. The duration of treatment is generally five to seven days 15.

Recently, data has shown recorded emerging resistance to most classes of these drugs 15. Topical erythromycin has been a therapeutic choice for years; however, microbial resistance and unsatisfactory coverage for Haemophilus influenzae have limited its usefulness. Topical polymyxin B/trimethoprim and several fluoroquinolones effectively manage most cases of acute bacterial conjunctivitis 13, 15. Newer fluoroquinolones have the least documented resistance; however, they are costly 15. They should be considerations in areas of increased local antibiotic resistance 13, 19. Bacterial conjunctivitis secondary to gonococcal or chlamydial infections requires systemic treatment 5. Oral antibiotics are also indicated in cases of bacterial conjunctivitis with concurrent acute otitis media 15. Ophthalmia neonatorum secondary to Chlamydia trachomatis requires oral or intravenous erythromycin in addition to topical erythromycin for 14 days 13, 20, 21.When gonorrhea is the cause of the newborn infection, hospital admission, a single dose of intravenous or intramuscular ceftriaxone, and eye irrigation are the indicated therapy until resolution of the infection 5.

Follow up for acute bacterial conjunctivitis should be encouraged if there is no improvement in symptoms after one to two days 7.

Bacterial conjunctivitis prognosis

The prognosis for uncomplicated bacterial conjunctivitis is good with complete resolution and rare adverse events with both antibiotic treatment and expectant management strategies 5, 15.

- Hutnik C, Mohammad-Shahi MH. Bacterial conjunctivitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010 Dec 6;4:1451-7. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S10162[↩]

- Pippin MM, Le JK. Bacterial Conjunctivitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546683[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Basic and Clinical Science Course 2019-2020: External Disease and Cornea. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2019.[↩][↩]

- Conjunctivitis. https://eyewiki.org/Conjunctivitis[↩]

- Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23;310(16):1721-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280318. Erratum in: JAMA. 2014 Jan 1;311(1):95. Dosage error in article text.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Sheikh A, Hurwitz B. Topical antibiotics for acute bacterial conjunctivitis: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis update. Br J Gen Pract. 2005 Dec;55(521):962-4. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1570513/[↩][↩]

- Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008 Feb;86(1):5-17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01006.x[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Wan WL, Farkas GC, May WN, Robin JB. The clinical characteristics and course of adult gonococcal conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986 Nov 15;102(5):575-83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90527-1[↩]

- Chen YY, Liu SH, Nurmatov U, van Schayck OC, Kuo IC. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Mar 13;3(3):CD001211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001211.pub4[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library. CDC, 1977.[↩]

- Rothschild PR, Brezin AP, Dupin N. A 22-year-old man with chronic red eye and dysuria. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 Mar 20;2014:bcr2013202113. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202113[↩]

- Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23;310(16):1721-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280318. Erratum in: JAMA. 2014 Jan 1;311(1):95. Dosage error in article text[↩][↩]

- Beal C, Giordano B. Clinical Evaluation of Red Eyes in Pediatric Patients. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016 Sep-Oct;30(5):506-14. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.02.001[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Leung AKC, Hon KL, Wong AHC, Wong AS. Bacterial Conjunctivitis in Childhood: Etiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2018;12(2):120-127. doi: 10.2174/1872213X12666180129165718[↩]

- Pichichero ME. Bacterial conjunctivitis in children: antibacterial treatment options in an era of increasing drug resistance. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011 Jan;50(1):7-13. doi: 10.1177/0009922810379045[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Epling J. Bacterial conjunctivitis. BMJ Clin Evid. 2012 Feb 20;2012:0704. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3635545/[↩][↩]

- Patel PB, Diaz MC, Bennett JE, Attia MW. Clinical features of bacterial conjunctivitis in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2007 Jan;14(1):1-5. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.08.006[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Rietveld RP, ter Riet G, Bindels PJ, Sloos JH, van Weert HC. Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis: cohort study on informativeness of combinations of signs and symptoms. BMJ. 2004 Jul 24;329(7459):206-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38128.631319.AE[↩][↩]

- Chen FV, Chang TC, Cavuoto KM. Patient demographic and microbiology trends in bacterial conjunctivitis in children. J AAPOS. 2018 Feb;22(1):66-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2017.08.008[↩][↩]

- Zloto O, Gharaibeh A, Mezer E, Stankovic B, Isenberg S, Wygnanski-Jaffe T. Ophthalmia neonatorum treatment and prophylaxis: IPOSC global study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar;254(3):577-82. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3274-5[↩]

- Matejcek A, Goldman RD. Treatment and prevention of ophthalmia neonatorum. Can Fam Physician. 2013 Nov;59(11):1187-90. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3828094/[↩]