What is brachioradial pruritus

Brachioradial pruritus is a type of neurogenic itch syndrome of the upper extremities or a very intense burning sensation in the anterior distal third of arms and proximal third of forearms, corresponding to the proximal head of the brachioradialis muscle region 1, but involvement of the upper arms and shoulders is also common 2. Brachioradial pruritus may be unilateral or bilateral. Scratching reportedly only makes the discomfort worse, and most patients discover that application of cold packs is often the only therapy that provides symptomatic relief 3. Brachioradial pruritus was first described in Florida in 1968 by Waisman 4 and has since been reported from subtropical areas such as South Africa 5 and Hawaii 6. It is seen less frequently, but still with regularity, in temperate climes.

Early isolated case reports suggested that brachioradial pruritus was more common in males. Later larger studies revealed that brachioradial pruritus is seen more commonly in females than males in a ratio 3:1 7. The mean age at diagnosis is 59, but wide variations in age have been reported. Brachioradial pruritus is more common in lighter skin types, especially those with Fitzpatrick type I and type II skin, than in darker skin types. This factor further supports the role of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) in the pathogenesis of brachioradial pruritus.

Brachioradial pruritus has been associated with ultraviolet radiation (UVR), and some authors related to orthopedic lesions in the cervical spine such as cervical radiculopathy or neuropathy in the upper extremities 8. Despite the wide variety of causes for pruritus (itch), identification of brachioradial pruritus by dermatologists through the history and physical exam has been straightforward. Further workup, such as imaging, labs, and referral to specialists is rarely required. Therapeutic options are numerous and well-tolerated. Because of the benign transient nature of brachioradial pruritus, the number of reported cases and current studies are relatively low 7.

Brachioradial pruritus causes

While the cause of brachioradial pruritus has not completely been elucidated, current theories suggest brachioradial pruritus is a bifactorial process involving cervical nerve irritation and ultraviolet radiation (UVR) of the affected area 9.

A large majority of patients diagnosed with brachioradial pruritus will have a positive imaging study with evidence of one or more cervical spine abnormalities. Imaging with x-ray computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of patients with suspected or diagnosed brachioradial pruritus revealed cervical spine abnormalities such as degenerative joint disease, cervical nerve impingement due to disk herniation, osteoarthritis, foraminal stenosis, and others. degenerative joint disease has been reported as the most common cervical spine abnormality in patients with brachioradial pruritus. Many authors suggest that cervical spine disease between C5 to C8 is causative. The dermatomes of the dorsolateral arms are C5 to C6, and a cervical spine abnormality with evidence of radiculopathy at these levels would be especially suggestive as a cause for brachioradial pruritus. Despite the high frequency of cervical spine abnormalities on imaging, nearly all brachioradial pruritus patients imaged did not meet the criteria for a cervical radiculopathy. Additionally, only a minority of patients diagnosed with brachioradial pruritus are imaged. This suggests that a cervical radiculopathy not inclusive of radiologic criteria may be responsible for the high frequency of cervical spinal abnormalities in patients with brachioradial pruritus may simply be a confounding finding.

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is thought to be a contributing factor of brachioradial pruritus, and many patients report increased symptoms of brachioradial pruritus with sun exposure. The term brachioradial summer pruritus is also used in reference to the increased incidence of brachioradial pruritus during the warm summer months. A subset of histamine sensitive C-fibers is responsible for the transmission of pruritus. Excessive ultraviolet radiation (UVR) causes damage and a reduction of these C-fibers. Despite the reduction in cutaneous C-fiber number, increased pruritus is reported with ultraviolet radiation (UVR) in patients with brachioradial pruritus. This pruritic response to a stimulus that does not normally cause pruritus is known as alloknesis. Many patients report relief of symptoms during the winter months and with sun protection, which supports the role of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) as a trigger in brachioradial pruritus.

The absence of either radiographically evident cervical nerve irritation or ultraviolet radiation (UVR) does not preclude the diagnosis of brachioradial pruritus.

Brachioradial pruritus symptoms

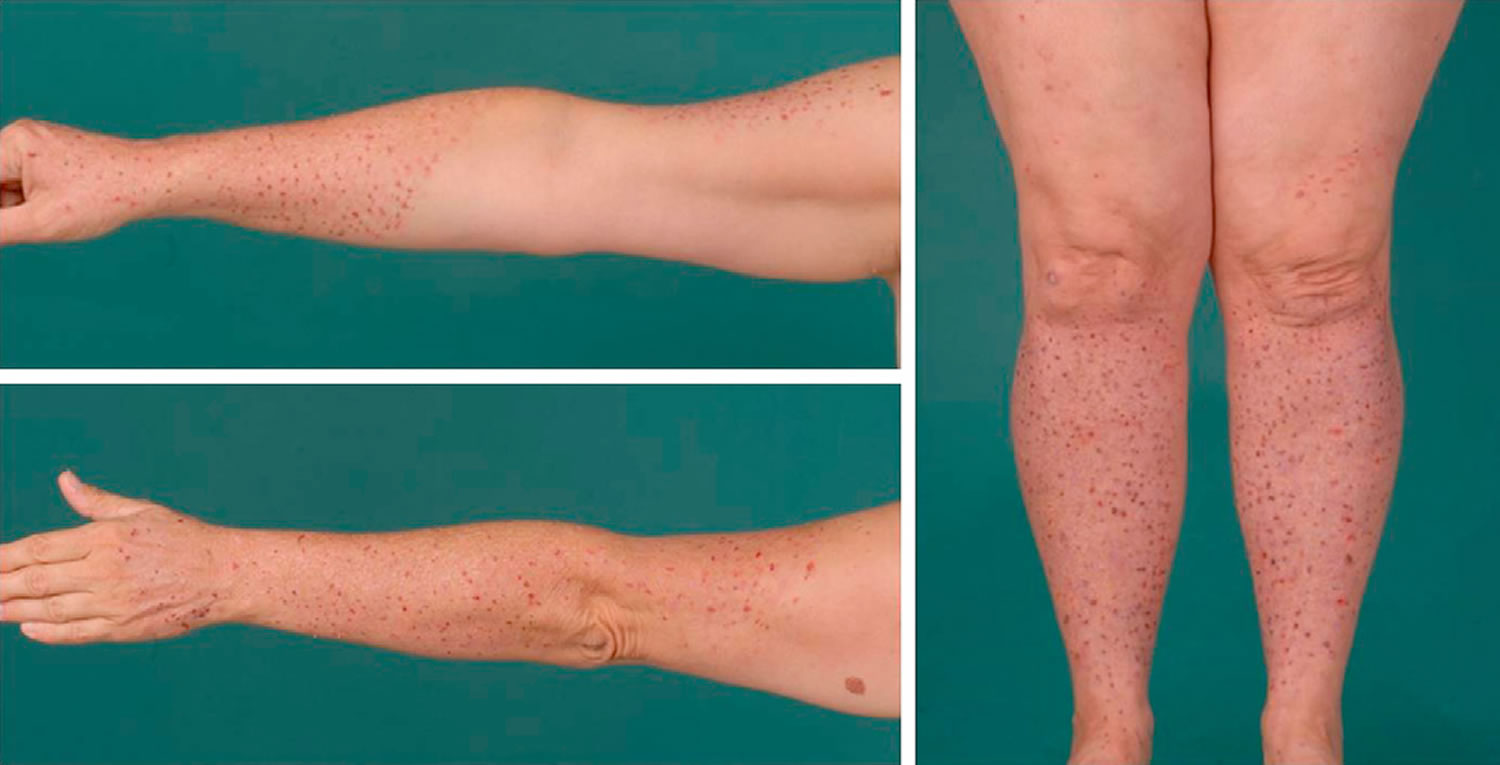

Because pruritus has many causes. The itch of brachioradial pruritus is described as intense, burning, and prickling. Brachioradial pruritus has a wide area of presentation but is most commonly reported on the dorsolateral aspects of the bilateral upper arms, forearms, and shoulders. Adjacent areas that may be affected are in the C5 to C6 dermatome and include the upper arms, shoulders, and neck. In addition to pruritus, patients may report pain, stinging, or tingling in the affected area. Brachioradial pruritus is bilateral approximately 75% of the time 10. Scratching is reported to make the discomfort worse, and many patients find that the only therapy that brings relief is the application of ice packs or cold, wet towels 11. The discomfort is typically worse at night and, for some patients, may interfere with falling asleep 4.

Symptoms are usually present for 2 to 3 years before diagnosis. Patients are typically outdoor enthusiasts such as bikers, hikers, and tanners and may have an extensive history of sunburn. Despite the high frequency of cervical spine abnormalities seen on imaging in patients with brachioradial pruritus, retrospective studies report that very few patients had complaints of neck pain, cervical spine narrowing, or neck trauma.

The median duration of symptoms has been reported as 4.5 years 2, but patients have reported a continuation of symptoms from this condition for as long as 18 years 5. Rarely, patients may initially experience symptoms typical of brachioradial pruritus, followed by the onset of generalized pruritus 12.

Brachioradial pruritus diagnosis

The physical exam of the affected areas is not impressive and lacks primary cutaneous lesions. Secondary cutaneous lesions such as excoriations, prurigo nodules, or lichenification may be present due to excessive scratching.

Confounding factors include coexistent chronic pruritic conditions, skin diseases, topical or systemic medications and unusual presentations.

The ice-pack sign is considered pathognomonic for brachioradial pruritus. The test is simple and involves placing an ice-pack to the affected area. The patient should report immediate improvement of pruritus that returns shortly after removal of the ice-pack.

Evaluations beyond a thorough history and physical and the ice-pack test are typically unnecessary. Imaging, blood tests, and referrals to appropriate specialists may be required in recalcitrant cases. Imaging modalities such as x-ray, CT, and MRI usually are not required. If imaging of the cervical spine is desired, MRI is the preferred modality. Screening blood work for causes of chronic pruritus can be performed. Referral to neurology for further examinations may be appropriate if a neurological cause is suspected. Neurological examinations include cervical spine imaging and electromyography (EMG).

Brachioradial pruritus treatment

The diagnosis and management of brachioradial pruritus is very difficult and thus it is managed by a multidisciplinary team that includes a neurologist, hand surgeon, dermatologist, nurse practitioner, primary care provider, internist, and psychiatrist 7. Brachioradial pruritus is more common in middle-aged white females with a seasonal predilection for warmer summer months. Cervical radiculopathy or neuropathy in the upper extremities in conjunction with ultraviolet radiation (UVR) are thought to be causative.

There are hundreds of treatment for rachioradial pruritus but none works reliably or is better than other treatments. Patients go through exhaustive workup to determine the cause, which is never found in most cases.

Treatment includes avoidance of ultraviolet radiation (UVR), topical medications, systemic medications and in select cases, surgery.

Methods of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) avoidance include reducing sun exposure, judicious use of sunscreen, and use of long-sleeved UV-protective clothing. This may be difficult for some brachioradial pruritus patients, as many enjoy outdoor activities during the warm summer season. Topical medications include capsaicin, mild steroids, anesthetics, antihistamines, and amitriptyline/ketamine. Earlier reports stated topical capsaicin was the most commonly prescribed initial therapy. A newer study reported the oral tricyclic antidepressant, amitriptyline, was the most commonly prescribed medication for brachioradial pruritus, although gabapentin may be more efficacious. Other oral medications include risperidone, fluoxetine, chlorpromazine, and hydroxyzine. For unknown reasons, systemic antihistamine therapies are ineffective in brachioradial pruritus. Response to treatment was greatest in patients who rated their pruritus as severe and those that continued with longer treatments 13. It should be noted that the sample size of most studies are small and differences in the most prescribed and efficacious therapy vary. Surgery was reserved for patients with a correctable cervical spinal abnormality seen on imaging. Very few patients fall into this category.

Cervical nerve blocks have been reported to be unhelpful 11, but cervical spine manipulation is effective in some patients 14. Cutaneous field stimulation has also been used. In one study, patients receiving 20 minutes of this treatment to affected areas once daily reported significant symptomatic improvement after 5 weeks 15.

Acupuncture may be helpful for symptomatic relief. Stellon 16 performed a retrospective case series of 16 patients with brachioradial pruritus using deep intramuscular stimulation acupuncture to the paravertebral muscles in the dermatomal segments of the body affected by the pruritus. Treatment was also given to other segments of the body not affected by the pruritus if paravertebral spasm and tenderness was detected. After a median of 4 treatments, 12 of 16 patients reported complete resolution of symptoms and 4 patients reported partial resolution. Relapse occurred in 6 patients within 1-12 months of cessation of acupuncture.

One report 17 describes dramatic improvement after injections with botulinum toxin A (100 IU/3 mL saline) in a 59-year-old white woman with longstanding brachioradial pruritus. This patient received 4 series of injections and experienced significant improvement for 6 months following each series of injections. The authors point out that acetylcholine has been shown to be a mediator of itch in patients with atopic dermatitis, and they suggest that reduction in acetylcholine release mediated by botulinum toxin A may explain its helpfulness in the setting of brachioradial pruritus. They also postulate that botulinum toxin A may reduce histamine-mediated itch.

A compounded mixture of amitriptyline hydrochloride 1.0%, ketamine hydrochloride 0.5%, and Vanicream applied 2-3 times daily was reported to provide complete relief to an adult patient with a 5-year history of brachioradial pruritus unresponsive to conventional treatments 18.

Aprepitant, a neurokinin-1 receptor inhibitor, can also be effective, even in long-standing disease refractory to conventional treatments 19.

Brachioradial pruritus prognosis

Most patients with brachioradial pruritus have remissions, but a small percentage have chronic disease. Emotional or psychiatric factors likely play a role in prognosis.

- Pereira, José Marcos. (2005). Brachioradial pruritus treated with thalidomide. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, 80(3), 295-296. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0365-05962005000300012[↩]

- Veien NK, Hattel T, Laurberg G, Spaun E. Brachioradial pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 Apr. 44(4):704-5.[↩][↩]

- Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Medical pearl: the ice-pack sign in brachioradial pruritus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Jun. 52(6):1073.[↩]

- Waisman M. Solar pruritus of the elbows (brachioradial summer pruritus). Arch Dermatol. 1968 Nov. 98(5):481-5.[↩][↩]

- Heyl T. Brachioradial pruritus. Arch Dermatol. 1983 Feb. 119(2):115-6.[↩][↩]

- Walcyk PJ, Elpern DJ. Brachioradial pruritus: a tropical dermopathy. Br J Dermatol. 1986 Aug. 115(2):177-80.[↩]

- Robbins BA, Schmieder GJ. Brachioradial Pruritus. [Updated 2019 May 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459321[↩][↩][↩]

- Weinberg BD, Amans M, Deviren S, Berger T, Shah V. Brachioradial pruritus treated with computed tomography-guided cervical nerve root block: A case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2018 Aug;4(7):640-644.[↩]

- Alai NN, Skinner HB. Concurrent notalgia paresthetica and brachioradial pruritus associated with cervical degenerative disc disease. Cutis. 2018 Sep;102(3):185;186;189;190.[↩]

- Atış G, Bilir Kaya B. Pregabalin treatment of three cases with brachioradial pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2017 Mar;30, 2.[↩]

- Crevits L. Brachioradial pruritus–a peculiar neuropathic disorder. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006 Dec. 108(8):803-5.[↩][↩]

- Kwatra SG, Stander S, Bernhard JD, Weisshaar E, Yosipovitch G. Brachioradial pruritus: a trigger for generalization of itch. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 May. 68(5):870-3.[↩]

- Pereira MP, Lüling H, Dieckhöfer A, Steinke S, Zeidler C, Agelopoulos K, Ständer S. Application of an 8% capsaicin patch normalizes epidermal TRPV1 expression but not the decreased intraepidermal nerve fibre density in patients with brachioradial pruritus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Sep;32(9):1535-1541.[↩]

- Tait CP, Grigg E, Quirk CJ. Brachioradial pruritus and cervical spine manipulation. Australas J Dermatol. 1998 Aug. 39(3):168-70.[↩]

- Wallengren J, Sundler F. Cutaneous field stimulation in the treatment of severe itch. Arch Dermatol. 2001 Oct. 137(10):1323-5.[↩]

- Stellon A. Neurogenic pruritus: an unrecognised problem? A retrospective case series of treatment by acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2002 Dec. 20(4):186-90.[↩]

- Kavanagh GM, Tidman MJ. Botulinum A toxin and brachioradial pruritus. Br J Dermatol. 2012 May. 166(5):1147.[↩]

- Poterucha TJ, Murphy SL, Davis MD, Sandroni P, Rho RH, Warndahl RA, et al. Topical amitriptyline-ketamine for the treatment of brachioradial pruritus. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Feb. 149(2):148-50[↩]

- He A, Alhariri JM, Sweren RJ, Kwatra MM, Kwatra SG. Aprepitant for the Treatment of Chronic Refractory Pruritus. Biomed Res Int. 2017. 2017:4790810.[↩]