What is Sleep Apnea ?

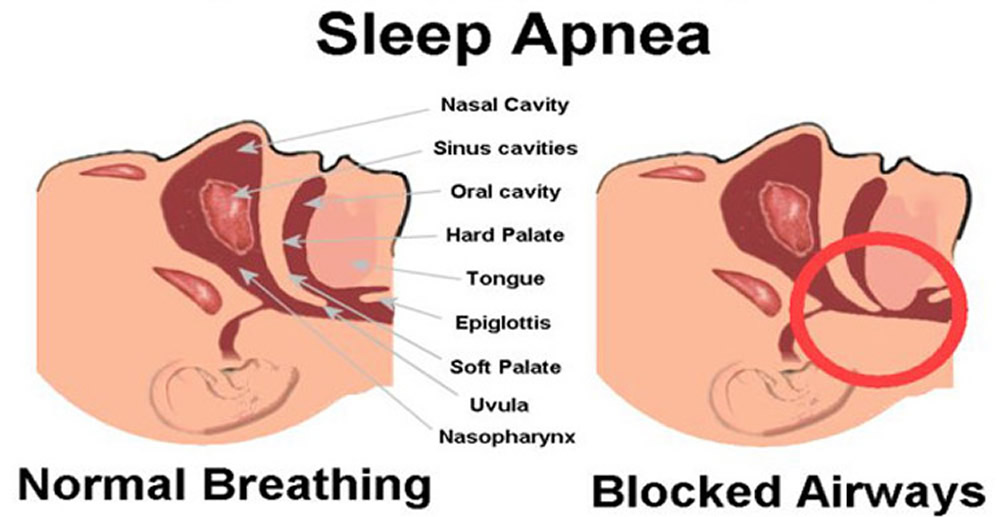

Obstructive sleep apnea is a potentially serious sleep disorder in which breathing repeatedly stops and starts. It is caused by collapse of the upper airways during sleep and is strongly associated with obesity.

The main symptom of obstructive sleep apnea is daytime sleepiness and it has been suggested it is linked to premature death, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, stroke and road traffic accidents.

Sleep apnea does not make you gain weight. However, you’re more likely to have sleep apnea if you’re overweight or morbidly obese, a man, African-American, or Latino. Weight has a direct effect on diagnosis of sleep apnea. People who are heavier tend to have severe sleep apnea. The heavier you are, the severer the sleep apnea usually is. Around half the people with obstructive sleep apnea are overweight. Fat deposits around the upper airway may obstruct breathing. However, not everyone with obstructive sleep apnea is overweight and vice versa. We look at a BMI, which is Body Mass Index. If it’s above 30, it is considered obesity, if it’s above 40, it is considered morbid obesity. And the disorder also tends to run in families.

There are more than 80 different sleep disorders and there are several types of sleep apnea, but the most common is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This type of apnea occurs when your throat muscles intermittently relax and block your airway during sleep. A noticeable sign of obstructive sleep apnea is snoring, but not everyone who has sleep apnea snores !

People with obstructive sleep apnea may not be aware that their sleep was interrupted. In fact, some people with this type of sleep apnea think they sleep well all night.

When the muscles relax, your airway narrows or closes as you breathe in, and you can’t get an adequate breath in. This may lower the level of oxygen in your blood. Your brain senses this inability to breathe and briefly rouses you from sleep so that you can reopen your airway. This awakening is usually so brief that you don’t remember it.

You may make a snorting, choking or gasping sound. This pattern can repeat itself five to 30 times or more each hour, all night long. People with the condition actually stop breathing up to 400 times throughout the night. These pauses last 10 to 30 seconds, and they’re usually followed by a snort when breathing starts again. This breaks your sleep cycle and can leave you tired during the day. All those breaks in sleep take a toll on your body and mind. These disruptions impair your ability to reach the desired deep, restful phases of sleep, and you’ll probably feel sleepy during your waking hours. When the condition goes untreated, it’s been linked to job-related injuries, car accidents, heart attacks, and strokes.

The most common signs and symptoms of obstructive and central sleep apneas include:

- Loud snoring, which is usually more prominent in obstructive sleep apnea

- Episodes of breathing cessation during sleep witnessed by another person

- Abrupt awakenings accompanied by shortness of breath, which more likely indicates central sleep apnea

- Awakening with a dry mouth or sore throat

- Morning headache

- Difficulty staying asleep (insomnia)

- Excessive daytime sleepiness (hypersomnia)

- Attention problems

- Irritability.

Consult a medical professional if you experience, or if your partner notices, the following:

- Snoring loud enough to disturb the sleep of others or yourself

- Shortness of breath, gasping for air or choking that awakens you from sleep

- Intermittent pauses in your breathing during sleep

- Excessive daytime drowsiness, which may cause you to fall asleep while you’re working, watching television or even driving

There are no certain foods that will help with sleep apnea, but losing weight by eating a low-calorie, low-fat diet and increasing your exercise will definitely help you manage your sleep apnea better. It’s best you avoid caffeine. And of course, you should avoid high-fat, high-calorie diets. We also highly recommend avoiding alcohol, narcotics, sedatives. Anything that makes you more sleepy will make your sleep apnea worse. Alcohol relaxes the muscles in the back of your throat. That makes it easier for the airway to become blocked in people with sleep apnea. Sleeping pills have the same effect.

If you sleep on your back, gravity can pull the tissues in the throat down, where they’re more likely to block your airway. Sleep on your side instead to open your throat. Certain pillows can help keep you on your side. Some people even go to bed in shirts with tennis balls sewn onto the back.

A dentist or orthodontist can fit you with a mouthpiece or oral appliance to ease mild sleep apnea. The device is custom-made for you, and it adjusts the position of your lower jaw and tongue. You put it in at bedtime to help keep your airway open while you sleep.

Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

The mainstay of medical treatment is a machine used at night to apply continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP). The machine blows air through the upper air passages via a mask on the mouth or nose to keep the throat open. You can adjust the flow until it’s strong enough to keep your airway open while you sleep. It’s the most common treatment for adults with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea.

Reviewed of all randomised controlled trials (source 1) that had been undertaken to evaluate the benefit of CPAP in adult patients with sleep apnoea. The overall results demonstrate that in people with moderate to severe sleep apnoea, continuous positive airways pressure can improve measures of sleepiness, quality of life, bodily pain and associated daytime sleepiness 2. CPAP leads to lower blood pressure compared with control, although the degree to which this is achieved may depend upon whether people start treatment with raised blood pressures. Oral appliances are also used to treat sleep apnoea but, whilst some people find them more convenient to use than CPAP, they do not appear to be as effective at keeping the airway open at night. Further good quality trials are needed to define who benefits, by how much and at what cost. Further trials are also needed to evaluate the effectiveness of CPAP in comparison to other interventions, particularly those targeted at obesity.

Almost all of us require 7-8 hours sleep per night. For optimal neurocognitive function, you may require 9 hours of sleep per 24 hour period. After 18 hours without sleep, your cognitive function falls to the equivalent of 1 alcholic drink and at 24 hours of sleep deprivation, you are legally “drunk” 3. These data suggest that chronic sleep restriction (insufficient sleep duration over consecutive days), commonplace in millions of Americans, can negatively impact cognitive performance immediately upon awakening and have prolonged effects for at least one hour, even in the absence of extended wakefulness. Young adults’ performance on spatial working memory task deteriorated following cumulative sleep deprivation whereas their performance on decision making task was not affected. The present study indicates that sleep deprivation has a differential impact on the neurobehavioural functoning of young adults 4. In adolescents (aged 15 to 17 years), who are sleep deprived, suffered from dose-dependent and time-of-day dependent deficits to sustained attention 5. These findings are important for individuals needing to perform tasks quickly upon awakening, especially those who do not regularly obtain sufficient sleep 6. And in voluntary experimental sleep restriction (an experiment on volunteers who are sleep restricted) results in decreases in self-reported psychological health and wellbeing and increases in measures of inflammation 7.

There are more and more data that support a link between obesity and insufficient sleep. The growth of America’s obesity epidemic over the past 40 years correlates with a progressive decline in the amount of sleep reported by the average adult. In large population-based studies, obesity has been found to be related to reduced amounts of sleep (see Figure 1 below) 3.

Sleep restriction or chronic partial sleep loss, increases obesity and diabetes risk by disrupting glucose metabolism and reducing whole-body insulin sensitivity without a compensatory increase in insulin secretion. Healthy adipocytes suppress hormone sensitive lipase activity in response to insulin, which severely limits non-esterified fatty acid release. Elevated overnight non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels are correlated with the reduction in insulin sensitivity that occurs in sleep restriction. Additionally, subcutaneous adipose biopsies from sleep-restricted subjects have reduced pAKT, evidence that sleep restriction decreases insulin sensitivity in adipocytes. Sleep restriction induces symmetrical changes in both glucose and lipid markers of insulin sensitivity. Preliminary evidence indicates that non-esterified fatty acid rate of utilization is increased in response to sleep restriction. In the context of whole-body metabolism, this indicates a shift in Randle cycle fuel selection by metabolic tissues. Additionally, a greater concentration of glucose was required to initiate non-esterified fatty acid suppression, evidence that sleep restriction functionally impairs hormone sensitive lipase activity 8.

A recent experimental study 9 published in the journal Sleep provides some clues. Sleep restriction to 4.5 hours per night was compared with normal sleep duration for 4 nights each in a group of young, healthy adults. When measured at the end of 4 days, the ratio of 2 hormones responsible for hunger levels, ghrelin (which increases appetite) and leptin (which reduces appetite) was altered to favor greater appetite. Other studies have observed the same thing. However, this study measured something the others hadn’t: snack consumption, particularly items with greater fat and protein content, was higher after sleep restriction — and, strikingly, the participants’ levels of endocannabinoids increased corresponding to the time of greater snack consumption. Endocannabinoids are chemicals that kindle appetite (like ghrelin), but more importantly, also stimulate reward centers in the brain. Thus, this finding suggests that sleep restriction may make the act of eating more satisfying. Could it be that insufficient sleep contributes to weight gain by stimulating the brain to make eating more pleasurable ? If so, the “lack of willpower” may not be due to personal weakness, but rather a result of an addictive chemical imbalance resulting from sleep loss 10.

Lack of sufficient sleep may also compromise the effectiveness of your typical weight loss diets for weight loss and related metabolic risk reduction. Sleep deprivation decreased the proportion of weight lost as fat by 55% and increased the loss of lean-body mass by 60% 3. The amount of sleep contributes to the maintenance of fat-free body mass at time of caloric restriction (reduced calorie intake). For example, night-shift worker often have more metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Sleep restriction and circadian misalignment have been shown to decrease glucose tolerance. In an experiment 11 involving restricting the sleep time to 5h for five nights, researchers have been able to show that subjects blood glucose become impaired and elevated after a oral glucose tolerance test (a test to diagnose diabetes). Despite the test subjects were also given a one 8h recovery sleep episode, their blood glucose impairment remains. However, a one night of sleep deprivation did not affect glucose tolerance and did not add to the effects of prior sleep restriction 11.

In addition, chronic sleep loss for five days also exhibited long-lasting effects on the reduction of positive affect which were not reset by one recovery night. (Positive affect helps people cope with difficult situations. People with high positive affect have been shown to be happier, have more success in life and better relationships than people scoring low). Positive affect decreased further following acute sleep deprivation, indicating that people’s sleep curtailing lifestyles could make them more vulnerable to additional acute sleep loss. Five days of chronically reduced sleep exhibited a comparable reduction in positive affect as a sleepless night 12.

The study also showed that repetitive sleep deprivation and sleep disruption resulted greater feelings of fatigue and sleepiness, which could indicate a greater health and safety risk, that will not resolve with just a single night of recovery sleep 13.

Night-shift workers (see Figure 1), often have sleep disorders (which can become chronic), gastroinstestinal disease, increased incidence of cardiovascular disease, increased triglyceride and possibly an increase in late-onset diabetes 3.

Figure 1. Showing the number of hours sleep and the body weight gain over the years.

[Source 3 ]All these exciting findings require further investigation. However, they already provide additional evidence that sufficient sleep is important for optimal health, and in particular, for combating obesity. They also suggests that greater efforts need to be made on the part of the general public to get the 7 hours or more of nightly sleep as recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Summary Sleep Deprivation and Sleep Apnea

- Causes are multifactorial and complex

- Inadequate sleep has major health consequences

- Impaired brain function not surprising

- Increased metabolic and cardiovascular complications, like weight gain and more respiratory events, also present

- Research data are evolving.

Sleep Deprivation and Childhood Obesity

Dozens of studies spanning five continents have looked at the link between sleep duration and obesity in children. Most (but not all) have found a convincing association between too little sleep and increased weight 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. The strongest evidence has come from studies that have tracked the sleep habits of large numbers of children over long periods of time (longitudinal studies), and have also adjusted for the many other factors that could increase children’s obesity risk, such as parents’ obesity, television time, and physical activity.

A British study, for example, that followed more than 8,000 children from birth found that those who slept fewer than 10 and a half hours a night at age 3 had a 45 percent higher risk of becoming obese by age 7, compared to children who slept more than 12 hours a night 15. Similarly, Project Viva, a U.S. prospective cohort study of 915 children, found that infants who averaged fewer than 12 hours of sleep a day had twice the odds of being obese at age 3, compared with those who slept for 12 hours or more 18. Maternal depression during pregnancy, introduction of solid foods before the age of 4 months, and infant TV viewing were all associated with shorter sleep duration 21.

Childhood sleep habits may even have a long-term effect on weight, well into adulthood. Researchers in New Zealand followed 1,037 children from birth until age 32, collecting information from parents on the average number of hours their children slept at ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 20. Each one hour reduction in sleep during childhood was associated with a 50 percent higher risk of obesity at age 32.

Keep in mind that these are all observational studies-and even though they suggest an association between sleep and weight, they cannot conclusively show that getting enough sleep lowers children’s risk of obesity. More definitive answers may come from randomized clinical trials that test whether increasing infant or childhood sleep lowers the risk of obesity.

The first such trial to look at the influence of a sleep intervention on childhood obesity, fielded in Australia, enrolled 328 7-month-old infants who already had sleep problems, as reported by their mothers 22. The trial sought to test whether counseling mothers on behavioral techniques to manage infant sleep problems would improve infants’ sleep and also lower mothers’ rates of depression; the researchers followed up at intervals over six years to see if the intervention had any effect on obesity. At one year of age, infants in the intervention group had fewer reported sleep problems than infants in the control group, but there was no difference in sleep duration between the groups; at 2 and 6 years of age, there was no difference in sleep problems or sleep duration between the groups. Thus, it is perhaps no surprise that at 6 years of age, obesity rates were the same in both groups. The study also had serious shortcomings, among them, the fact that 40 percent of the participants had dropped out by the six-year follow-up.

Two large trials currently underway, one in the U.S. and the other in New Zealand, should offer more conclusive evidence on the relationship between sleep duration and obesity 23, 24. Both trials are testing whether teaching parents how to develop good sleep and feeding habits in their newborn infants helps prevent the development of obesity during the toddler years. Early results from the U.S. study have been encouraging 23.

Sleep Deprivation and Adult Obesity

Most studies that measure adults’ sleep habits at one point in time (cross-sectional studies) have found a link between short sleep duration and obesity 14. Longitudinal studies, though, can better answer questions about causality-and in adults the findings from such studies have been less consistent than those in children 25.

The largest and longest study to date on adult sleep habits and weight is the Nurses’ Health Study, which followed 68,000 middle-age American women for up to 16 years 26. Compared to women who slept seven hours a night, women who slept five hours or less were 15 percent more likely to become obese over the course of the study. A similar investigation in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Nurses’ Health Study II, a cohort of younger women, looked at the relationship between working a rotating night shift-an irregular schedule that mixes day and evening work with a few night shifts, throwing off circadian rhythms and impairing sleep-and risk of type 2 diabetes and obesity 27. Researchers found that the longer women worked a rotating night shift, the greater their risk of developing diabetes and obesity.

Other researchers have fielded smaller, shorter longitudinal studies on adult sleep habits and weight in the U.S. and Canada as well as the U.K. and Europe 25. Some have found a link between short sleep duration and obesity, while others have not. Interestingly, a few studies in adults have reported that getting too much sleep is linked to a higher risk of obesity 26, 28. This is most likely due to a phenomenon that researchers call “reverse causation.” People who sleep for longer than normal may have an obesity-related condition that has led to their longer sleep habits-sleep apnea, obstructive lung disease, depression, or cancer, for example-rather than long sleep coming first and then leading to obesity.

An in-process pilot study may provide more answers on whether getting a longer night’s sleep can help with weight loss 29. Researchers are recruiting 150 obese adults who are “short sleepers” (who sleep fewer than 6.5 hours a night) and randomly assigning them to either maintain their current sleep habits or else receive coaching on how to extend their nightly sleep by at least half an hour to an hour. Investigators will track study participants’ sleep habits and weight for three years.

How Does Sleep Affect Your Body Weight

Researchers speculate that there are several ways that chronic sleep deprivation might lead to weight gain, either by increasing how much food people eat or decreasing the energy that they burn 14.

Sleep deprivation could increase your energy intake by

- Increasing hunger: Sleep deprivation may alter the hormones that control hunger 30. One small study, for example, found that young men who were deprived of sleep had higher levels of the appetite-stimulating hormone ghrelin and lower levels of the satiety-inducing hormone leptin, with a corresponding increase in hunger and appetite-especially for foods rich in fat and carbohydrates 31.

- Giving you more time to eat: People who sleep less each night may eat more than people who get a full night’s sleep simply because they have more waking time available 32. Recently, a small laboratory study found that people who were deprived of sleep and surrounded by tasty snacks tended to snack more-especially during the extra hours they were awake at night-than when they had adequate sleep 33.

- Prompting you to choose less healthy diets: Observational studies have not seen a consistent link between sleep and food choices 14. But one study of Japanese workers did find that workers who slept fewer than six hours a night were more likely to eat out, have irregular meal patterns, and snack than those who slept more than six hours 34.

Sleep deprivation could decrease your energy expenditure by

- Decreasing your physical activity: People who don’t get enough sleep are more tired during the day, and as a result may curb their physical activity 26. Some studies have found that sleep-deprived people tend to spend more time watching TV, less time playing organized sports, and less time being physically active than people who get enough sleep. But these differences in physical activity or TV viewing are not large enough to explain the association between sleep and weight 35.

- Lowering your body temperature: In laboratory experiments, people who are sleep-deprived tend to see a drop in their body temperatures 35. This drop, in turn, may lead to decreased energy expenditure. Yet a recent study did not find any link between sleep duration and total energy expenditure 36.

Twelve Simple Tips to Improve Your Sleep

Following healthy sleep habits can make the difference between restlessness and restful slumber 37. Researchers have identified a variety of practices and habits—known as “sleep hygiene”—that can help anyone maximize the hours they spend sleeping, even those whose sleep is affected by insomnia, jet lag, or shift work.

Sleep hygiene may sound unimaginative, but it just may be the best way to get the sleep you need in this 24/7 age. Here are some simple tips 37 for making the sleep of your dreams a nightly reality:

1) Avoid Caffeine, Alcohol, Nicotine, and Other Chemicals that Interfere with Sleep

As any coffee lover knows, caffeine is a stimulant that can keep you awake. So avoid caffeine (found in coffee, tea, chocolate, cola, and some pain relievers) for four to six hours before bedtime. Similarly, smokers should refrain from using tobacco products too close to bedtime.

Although alcohol may help bring on sleep, after a few hours it acts as a stimulant, increasing the number of awakenings and generally decreasing the quality of sleep later in the night. It is therefore best to limit alcohol consumption to one to two drinks per day, or less, and to avoid drinking within three hours of bedtime.

2) Turn Your Bedroom into a Sleep-Inducing Environment

A quiet, dark, and cool environment can help promote sound slumber. Why do you think bats congregate in caves for their daytime sleep ? To achieve such an environment, lower the volume of outside noise with earplugs or a “white noise” appliance. Use heavy curtains, blackout shades, or an eye mask to block light, a powerful cue that tells the brain that it’s time to wake up. Keep the temperature comfortably cool—between 60 and 75°F—and the room well ventilated. And make sure your bedroom is equipped with a comfortable mattress and pillows.

Also, if a pet regularly wakes you during the night, you may want to consider keeping it out of your bedroom.

It may help to limit your bedroom activities to sleep and sex only. Keeping computers, TVs, and work materials out of the room will strengthen the mental association between your bedroom and sleep.

3) Establish a Soothing Pre-Sleep Routine

Ease the transition from wake time to sleep time with a period of relaxing activities an hour or so before bed. Take a bath (the rise, then fall in body temperature promotes drowsiness), read a book, watch television, or practice relaxation exercises. Avoid stressful, stimulating activities—doing work, discussing emotional issues. Physically and psychologically stressful activities can cause the body to secrete the stress hormone cortisol, which is associated with increasing alertness. If you tend to take your problems to bed, try writing them down—and then putting them aside.

4) Go to Sleep When You’re Truly Tired

Struggling to fall sleep just leads to frustration. If you’re not asleep after 20 minutes, get out of bed, go to another room, and do something relaxing, like reading or listening to music until you are tired enough to sleep.

5) Don’t Be a Nighttime Clock-Watcher

Staring at a clock in your bedroom, either when you are trying to fall asleep or when you wake in the middle of the night, can actually increase stress, making it harder to fall asleep. Turn your clock’s face away from you.

And if you wake up in the middle of the night and can’t get back to sleep in about 20 minutes, get up and engage in a quiet, restful activity such as reading or listening to music. And keep the lights dim; bright light can stimulate your internal clock. When your eyelids are drooping and you are ready to sleep, return to bed.

6) Use Light to Your Advantage

Natural light keeps your internal clock on a healthy sleep-wake cycle. So let in the light first thing in the morning and get out of the office for a sun break during the day.

7) Keep Your Internal Clock Set with a Consistent Sleep Schedule

Going to bed and waking up at the same time each day sets the body’s “internal clock” to expect sleep at a certain time night after night. Try to stick as closely as possible to your routine on weekends to avoid a Monday morning sleep hangover. Waking up at the same time each day is the very best way to set your clock, and even if you did not sleep well the night before, the extra sleep drive will help you consolidate sleep the following night.

8) Nap Early—Or Not at All

Many people make naps a regular part of their day. However, for those who find falling asleep or staying asleep through the night problematic, afternoon napping may be one of the culprits. This is because late-day naps decrease sleep drive. If you must nap, it’s better to keep it short and before 5 p.m.

9) Lighten Up on Evening Meals

Eating a pepperoni pizza at 10 p.m. may be a recipe for insomnia. Finish dinner several hours before bedtime and avoid foods that cause indigestion. If you get hungry at night, snack on foods that (in your experience) won’t disturb your sleep, perhaps dairy foods and carbohydrates.

10) Balance Fluid Intake

Drink enough fluid at night to keep from waking up thirsty—but not so much and so close to bedtime that you will be awakened by the need for a trip to the bathroom.

11) Exercise Early

Exercise can help you fall asleep faster and sleep more soundly—as long as it’s done at the right time. Exercise stimulates the body to secrete the stress hormone cortisol, which helps activate the alerting mechanism in the brain. This is fine, unless you’re trying to fall asleep. Try to finish exercising at least three hours before bed or work out earlier in the day.

12) Follow Through

Some of these tips will be easier to include in your daily and nightly routine than others. However, if you stick with them, your chances of achieving restful sleep will improve. That said, not all sleep problems are so easily treated and could signify the presence of a sleep disorder such as apnea, restless legs syndrome, narcolepsy, or another clinical sleep problem. If your sleep difficulties don’t improve through good sleep hygiene, you may want to consult your physician or a sleep specialist.

References- Cochrane Review 19 July 2006 – Continuous positive airways pressure for relieving signs and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea – http://www.cochrane.org/CD001106/AIRWAYS_continuous-positive-airways-pressure-for-relieving-signs-and-symptoms-of-obstructive-sleep-apnoea

- Sleep 17 April 2017, 40 (4): zsx040. Effect of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life and Sleepiness in High Cardiovascular Risk Individuals With Sleep Apnea: Best Apnea Interventions for Research (BestAIR) Trial. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/4/zsx040/3737623/Effect-of-Continuous-Positive-Airway-Pressure?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Lancet 2001. Effects of Shift Work on Patients with Sleep Disorders. https://content.sph.harvard.edu/ecpe/CourseMats/IPHM/2012_09_27_1425_MALHOTRA_01.pdf

- Sleep Published: 28 April 2017; (suppl_1): A92-A93. EXPERIMENTAL CUMULATIVE SLEEP RESTRICTION IMPAIRS WORKING MEMORY BUT NOT DECISION MAKING. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A92/3781471/0252-EXPERIMENTAL-CUMULATIVE-SLEEP-RESTRICTION?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep Published: 28 April 2017; 40 (suppl_1): A14. DOSE-DEPENDENT HOMEOSTATIC AND CIRCADIAN EFFECTS OF SLEEP RESTRICTION ON SUSTAINED ATTENTION IN ADOLESCENTS. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A14/3780914/0035-DOSE-DEPENDENT-HOMEOSTATIC-AND-CIRCADIAN?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep Published: 28 April 2017; (suppl_1): A76-A77. THE EFFECT OF SLEEP INERTIA AND CHRONIC SLEEP RESTRICTION ON HUMAN COGNITIVE PERFORMANCE. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/40/suppl_1/A76/3781414/0206-THE-EFFECT-OF-SLEEP-INERTIA-AND-CHRONIC-SLEEP?searchresult=1

- Sleep Published: 28 April 2017; 40 (suppl_1): A32. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleepj/zsx050.083. A COMPARISON OF VOLUNTARY AND EXPERIMENTAL SLEEP RESTRICTION GROUPS. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A32/3780981/0084-THE-PSYCHOLOGICAL-AND-PHYSIOLOGICAL?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep 28 April 2017, 40 (suppl_1): A27.ROLE OF SLEEP RESTRICTION IN ADIPOCYTE INSULIN SENSITIVITY DURING AN INTRAVENOUS GLUCOSE TOLERANCE TEST IN HEALTHY ADULT MEN. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A27/3780961/0071-ROLE-OF-SLEEP-RESTRICTION-IN-ADIPOCYTE?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep 28 April 2017, 40 (suppl_1): A73. THE EFFECTS OF SLEEP RESTRICTION ON FOOD INTAKE: THE IMPORTANCE OF INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A73/3781404/0198-THE-EFFECTS-OF-SLEEP-RESTRICTION-ON-FOOD?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep 28 April 2017, (suppl_1): A71-A72. ENERGY BALANCE RESPONSES SHOW PHENOTYPIC STABILITY TO SLEEP RESTRICTION AND TOTAL SLEEP DEPRIVATION IN HEALTHY ADULTS. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A71/3781398/0195-ENERGY-BALANCE-RESPONSES-SHOW-PHENOTYPIC?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep 28 April 2017, 40 (suppl_1): A27-A28. GLUCOSE TOLERANCE AFTER ACUTE SLEEP DEPRIVATION, SLEEP RESTRICTION, AND RECOVERY SLEEP. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A27/3780962/0072-GLUCOSE-TOLERANCE-AFTER-ACUTE-SLEEP?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep 28 April 2017, 40 (suppl_1): A56-A57. COMPARISON OF THE EFFECTS OF ACUTE TOTAL SLEEP DEPRIVATION, CHRONIC SLEEP RESTRICTION AND RECOVERY SLEEP ON POSITIVE AFFECT. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A56/3781336/0151-COMPARISON-OF-THE-EFFECTS-OF-ACUTE-TOTAL?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sleep 28 April 2017, 40 (suppl_1): A279. REPETITIVE SLEEP RESTRICTION AND SLEEP DISRUPTION LEADS TO ELEVATED SLEEPINESS AND FATIGUE THAT FAIL TO RESOLVE WITH A SINGLE NIGHT OF RECOVERY SLEEP. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-abstract/40/suppl_1/A279/3782185/0753-REPETITIVE-SLEEP-RESTRICTION-AND-SLEEP?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Patel SR, Hu FB. Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16:643-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18239586

- Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. BMJ. 2005; 330:1357. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15908441

- Agras WS, Hammer LD, McNicholas F, Kraemer HC. Risk factors for childhood overweight: a prospective study from birth to 9.5 years. J Pediatr. 2004; 145:20-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15238901

- Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Oken E, Rich-Edwards JW, Taveras EM. Developmental origins of childhood overweight: potential public health impact. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16:1651-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18451768

- Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Gunderson EP, Gillman MW. Short sleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008; 162:305-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18391138

- Bell JF, Zimmerman FJ. Shortened nighttime sleep duration in early life and subsequent childhood obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010; 164:840-5.

- Landhuis CE, Poulton R, Welch D, Hancox RJ. Childhood sleep time and long-term risk for obesity: a 32-year prospective birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008; 122:955-60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18977973

- Nevarez MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Associations of early life risk factors with infant sleep duration. Acad Pediatr. 2010; 10:187-93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20347414

- Wake M, Price A, Clifford S, Ukoumunne OC, Hiscock H. Does an intervention that improves infant sleep also improve overweight at age 6? Follow-up of a randomised trial. Arch Dis Child. 2011; 96:526-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21402578

- Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman SL, et al. Preventing obesity during infancy: a pilot study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011; 19:353-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20725058

- Prevention of Overweight in Infancy (POInz). ClinicalTrials.gov, 2009. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00892983

- Nielsen LS, Danielsen KV, Sorensen TI. Short sleep duration as a possible cause of obesity: critical analysis of the epidemiological evidence. Obes Rev. 2011; 12:78-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20345429

- Patel SR, Malhotra A, White DP, Gottlieb DJ, Hu FB. Association between reduced sleep and weight gain in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006; 164:947-54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16914506

- Pan A, Schernhammer ES, Sun Q, Hu FB. Rotating night shift work and risk of type 2 diabetes: two prospective cohort studies in women. PLoS Med. 2011; 8:e1001141. Epub 2011 Dec 6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22162955

- Chaput JP, Despres JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A. The association between sleep duration and weight gain in adults: a 6-year prospective study from the Quebec Family Study. Sleep. 2008; 31:517-23. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18457239

- Cizza G, Marincola P, Mattingly M, et al. Treatment of obesity with extension of sleep duration: a randomized, prospective, controlled trial. Clin Trials. 2010; 7:274-85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20423926

- Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004; 1:e62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15602591

- Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 141:846-50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15583226

- Taheri S. The link between short sleep duration and obesity: we should recommend more sleep to prevent obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2006; 91:881-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17056861

- Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Kasza K, Schoeller DA, Penev PD. Sleep curtailment is accompanied by increased intake of calories from snacks. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 89:126-33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19056602

- Imaki M, Hatanaka Y, Ogawa Y, Yoshida Y, Tanada S. An epidemiological study on relationship between the hours of sleep and life style factors in Japanese factory workers. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2002; 21:115-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12056178

- Patel SR, Hu FB. Short sleep duration and weight gain: a systematic review. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16:643-53. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18239586

- Manini TM, Everhart JE, Patel KV, et al. Daily activity energy expenditure and mortality among older adults. JAMA. 2006; 296:171-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16835422

- Harvard University, the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Twelve Simple Tips to Improve Your Sleep. http://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/healthy/getting/overcoming/tips