What is whiplash

Whiplash also known as neck sprain, is an injury to the muscles, tendons and other soft tissues of the neck 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Whiplash injury is caused by a sudden and vigorous movement of the head, sideways, backwards or forwards. Any impact that causes your head to suddenly accelerate or decelerate can cause symptoms of whiplash. However, sometimes whiplash result in no injury or pain at all 6.

The term “whiplash” injury was first coined by Harold Crowe in 1928 to define acceleration-deceleration injuries occurring to the cervical spine or neck region 7. Later modified to an all-encompassing term known as whiplash-associated disorders (WAD), these clinical entities have been refined to describe any collection of neck-related symptoms following a car accident 8, 9. Whiplash-associated disorder is a globally important clinical, social, and financial problem 10.

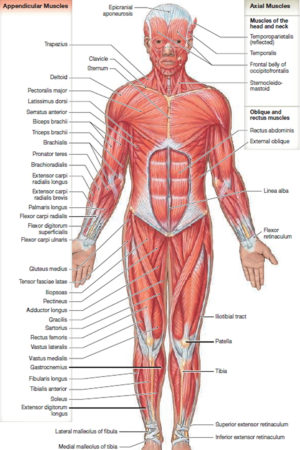

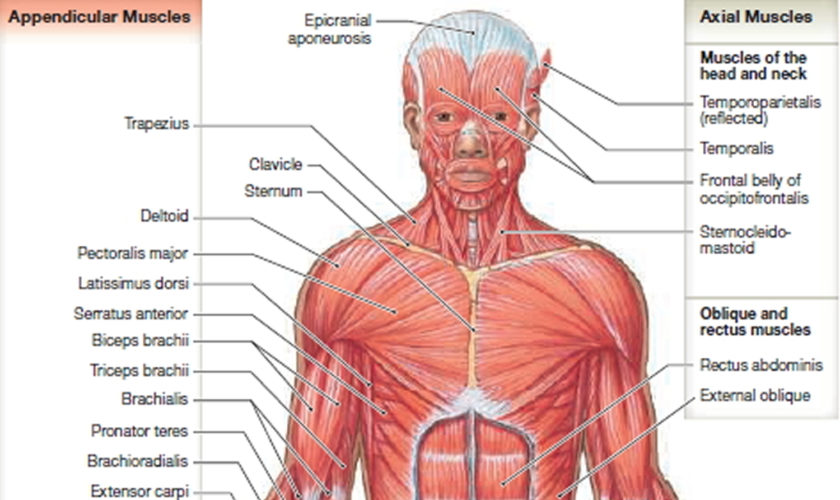

Your neck is made up by the cervical spine, the first seven vertebrae of the back (see Figure 1 below). Areas of the vertebrae commonly affected are the intervertebral joints (the joints between each vertebrae), the intervertebral discs (the soft material that cushions one vertebrae from another), and the ligaments, muscles and nerve roots that hold the vertebrae together.

Rear collision motor vehicle crashes are the most common cause of whiplash injuries. Whiplash injuries can also occur in other situations where the body is exposed to sudden starts and stops such as contact sports like football, rugby or soccer. Neck sprain or neck strain are other terms that are used to describe whiplash injuries.

Approximately 120,000 whiplash injuries occur in the US each year. The statistics vary for different countries. It is very interesting to find that Australia was the most prolific countries on whiplash injury, and the United States ranked second. A study of drivers in collisions involving two cars found similar results in French (1997–2003) and Spanish databases (2002–2004): 12.2% were diagnosed with whiplash in France and 12.0% in Spain 11. The annual economic cost of whiplash injury is estimated to be $3.9 billion in the United States 12.

Generally, whiplash injury causes acute neck pain and stiffness within hours of the accident, however these symptoms may in some cases be delayed for several days.

Pain should resolve with treatment after several weeks, and most patients are fully recovered within three months of the injury. Some individuals may continue to suffer pain and headaches after this.

Whiplash symptoms often greatly improve or disappear within a few days to weeks. It may take longer for symptoms to completely disappear and some people experience some pain and neck stiffness for months after a whiplash injury.

More than 50% of whiplash resolve after a few weeks of treatment 13, 14, 15. However, approximately 30% of cases develop long-term complex pain related disability and persist for months or years 16, 15. Recovery following whiplash injury, if it is to occur, will occur for the most part within the first 3 months post injury 17. Current estimates suggest that approximately 50% of individuals will recover by 3 months post injury, whilst the remainder will experience mild to moderate long-term disability 18, 19, 20. The development of chronic symptoms after whiplash injuries may also be influenced by psychological and social factors as well as with changes in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) 20, 21, 22. In countries such as Lithuania and Greece, where there is no compensation culture and no formal compensation system for late whiplash-related injuries, the development of chronic symptoms following whiplash is a rare phenomenon 23, 24. This evidence suggests that the culture and expectations around whiplash, local insurance systems, and the prospect of monetary benefits are likely to play important roles in the prevalence of whiplash injuries and related claims, as well as in the recovery process 25.

Common symptoms of whiplash include 26:

- neck pain and tenderness

- neck stiffness and difficulty moving your head

- headaches

- muscle spasms

- pain in the shoulders and arms

Less common symptoms include pins and needles in your arms and hands, dizziness, tiredness, memory loss, poor concentration and irritability.

It can take several hours for the symptoms to develop after you injure your neck. The symptoms are often worse the day after the injury, and may continue to get worse for several days.

Whiplash injuries are commonly caused by:

- motor vehicle accidents (80% of whiplash injury cases) 27, 28

- a sudden blow to the head from contact sports such as rugby or boxing

- being hit on the head by a heavy object

- a slip or fall where the head is jolted or jarred.

Whiplash occurs when the neck is moved beyond its usual range of movement, which overstretches or sprains the soft tissues of the neck (tendons, muscles and ligaments). This causes pain and discomfort in the neck and shoulders and may also cause back pain.

The joints and ligaments of the neck are covered by muscles. So whiplash injury cannot be seen from the surface. This can be frustrating when your neck is painful. Imagine a sprained ankle. Immediately following a sprain, the ankle becomes bruised, swollen and painful to move.

Key points about whiplash:

- Whiplash injury is poorly understood, but usually involves the muscles, discs, nerves, and tendons in your neck.

- It is caused by the neck bending forcibly forward and then backward, or vice versa.

- Many whiplash injuries occur if you are involved in a rear-end automobile collision.

- Your healthcare provider will determine specific treatment for your whiplash.

If severe neck pain occurs following an injury (motor vehicle accident, diving accident, or fall), a trained professional, such as a paramedic, should immobilize the patient to avoid the risk of further injury and possible paralysis. Medical care should be sought immediately.

Immediate medical care should also be sought when an injury causes pain in the neck that radiates down the arms and legs.

Radiating pain or numbness in your arms or legs causing weakness in the arms or legs without significant neck pain should also be evaluated.

If there has not been an injury, you should seek medical help right away if you have:

- A fever and headache, and your neck is so stiff that you cannot touch your chin to your chest. This may be meningitis. Call your local emergency number or get to a hospital.

- Symptoms of a heart attack, such as shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, vomiting, or arm or jaw pain.

- Neck pain that is:

- Continuous and persistent

- Severe

- Accompanied by pain that radiates down the arms or legs

- Accompanied by headaches, numbness, tingling, or weakness

See your doctor if:

- Symptoms do not go away in 1 week with self-care

- You have numbness, tingling, or weakness in your arm or hand

- Your neck pain was caused by a fall, blow, or injury — if you cannot move your arm or hand, have someone call your local emergency services number

- You have swollen glands or a lump in your neck

- Your pain does not go away with regular doses of over-the-counter pain medicine

- You have difficulty swallowing or breathing along with the neck pain

- The pain gets worse when you lie down or wakes you up at night

- Your pain is so severe that you cannot get comfortable

- You lose control over urination or bowel movements

- You have trouble walking and balancing

Cervical spine anatomy

Your spine is made up of 24 bones, called vertebrae, that are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Other parts of your spine include:

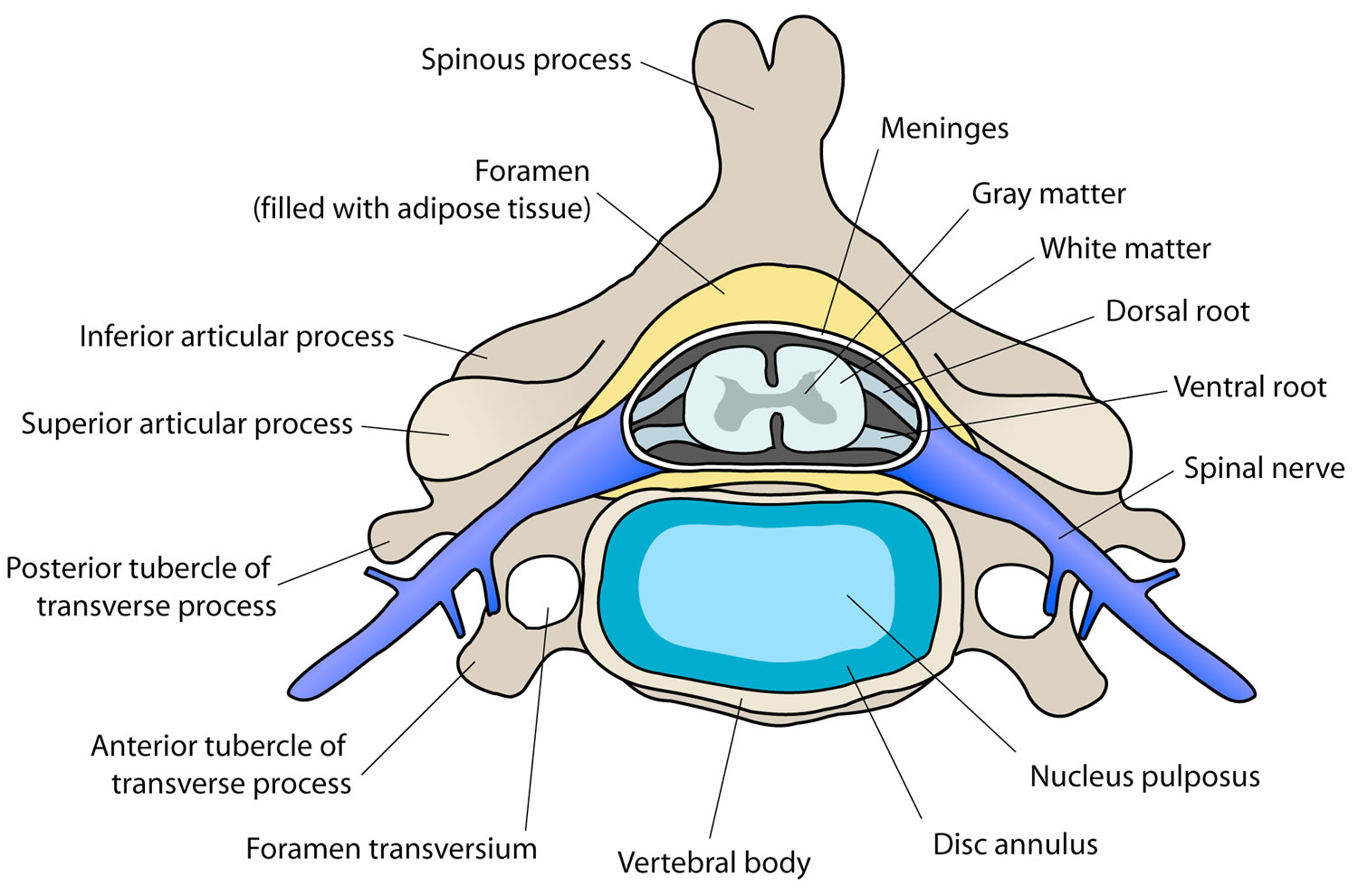

- Spinal cord and nerves. These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae (foramen).

- Intervertrebral disks. In between your vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. They act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Intervertebral disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. They are made up of two components:

- Annulus fibrosus. This is the tough, flexible outer ring of the disk.

- Nucleus pulposus. This is the soft, jelly-like center of the disk.

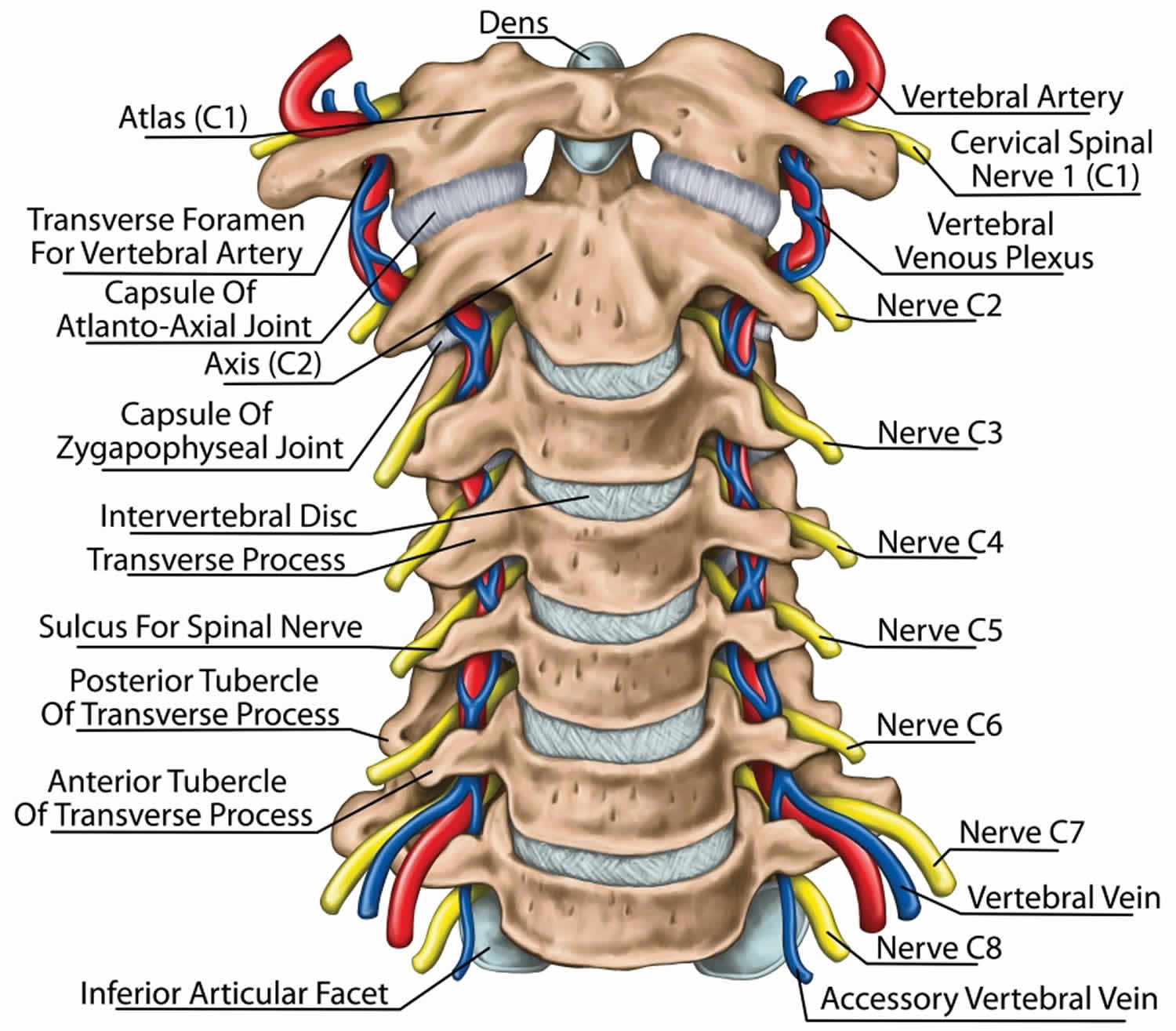

The cervical spine is made up of the first 7 vertebrae and functions to provide mobility and stability to the head, while connecting it to the relative immobile thoracic spine (see the image below). The first 2 vertebral bodies are quite different from the rest of the cervical spine. The atlas, or C1, articulates superiorly with the occiput and inferiorly with the axis, or C2.

The atlas is ring-shaped and does not have a body, unlike the rest of the vertebrae. The body has become part of C2, and it is called the odontoid process, or dens. The atlas is made up of an anterior arch, a posterior arch, 2 lateral masses, and 2 transverse processes. The transverse foramen, through which the vertebral artery passes, is enclosed by the transverse process. On each lateral mass is a superior and inferior facet (zygapophyseal) joint. The superior articular facets are kidney-shaped, concave, and face upward and inward. These superior facets articulate with the occipital condyles, which face downward and outward. The relatively flat inferior articular facets face downward and inward to articulate with the superior facets of the axis.

The axis has a large vertebral body, which contains the fused remnant of the C1 body, the dens. The dens articulates with the anterior arch of the atlas via its anterior articular facet and is held in place by the transverse ligament. The axis is composed of a vertebral body, heavy pedicles, laminae, and transverse processes, which serve as attachment points for muscles. The axis articulates with the atlas by its superior articular facets, which are convex and face upward and outward.

The remaining cervical vertebrae, C3-C7, are similar to each other, but they are very different from C1 and C2. They each have a vertebral body, which is concave on its superior surface and convex on its inferior surface. On the superior surfaces of the bodies are raised processes or hooks called uncinate processes, which articulate with depressed areas on the inferior aspect of the superior vertebral bodies called the echancrure or anvil. These uncovertebral joints are most noticeable near the pedicles and are usually referred to as the joints of Luschka 29. These joints are believed to be the result of degenerative changes in the annulus, which leads to fissuring in the annulus and the creation of the joint. The spinous processes of C3-C5 are usually bifid, in comparison to the spinous processes of C6 and C7, which are usually tapered.

The facet joints in the cervical spine are diarthrodial synovial joints with fibrous capsules. The joint capsules in the lower cervical spine are more lax compared with other areas of the spine to allow for gliding movements of the facets. The joints are inclined at 45° from the horizontal plane and angled 85° from the sagittal plane. This alignment helps to prevent excessive anterior translation and is important in weight bearing 30.

The fibrous capsules are innervated by mechanoreceptors (types I, II, and III), and free nerve endings have been found in the subsynovial loose areolar and dense capsular tissues 31. In fact, there are more mechanoreceptors in the cervical spine than in the lumbar spine 32. This neural input from the facets may be important for proprioception and pain sensation and may modulate protective muscular reflexes that are important in preventing joint instability and degeneration.

The facet joints in the cervical spine are innervated by both the anterior and dorsal rami. The occipitoatlantal joint and atlantoaxial joint are innervated by the ventral rami of the first and second cervical spinal nerves. Two branches of the dorsal ramus of the third cervical spinal nerve innervate the C2-C3 facet joint, a communicating branch and a medial branch known as the third occipital nerve.

The remaining cervical facets, C3-C4 to C7-T1, are supplied by the dorsal rami medial branches that arise one level cephalad and caudad to the joint 33. Therefore, each joint from C3-C4 to C7-T1 is innervated by the medial branches above and below. These medial branches send off articular branches to the facet joints as they wrap around the waists of the articular pillars.

Intervertebral discs are located between each vertebral body caudad to the axis. The discs are composed of 4 parts, including the nucleus pulposus in the middle, the annulus fibrosis surrounding the nucleus, and 2 end plates that are attached to the adjacent vertebral bodies. The discs are involved in cervical spine motion, stability, and weight bearing. The annular fibers are composed of collagenous sheets called lamellae, which are oriented 65-70° from the vertical and alternate in direction with each successive sheet. Therefore, the annular fibers are prone to injury with rotation forces because only one half of the lamellae are oriented to withstand the force in this direction 32. The middle and outer one third of the annulus is innervated by nociceptors, and phospholipase A2 has been found in the disc and may be an inflammatory mediator 34.

Several ligaments of the cervical spine, which provide stability and proprioceptive feedback, are worth mentioning 35. The transverse ligament, the major portion of the cruciate ligament, arises from tubercles on the atlas and stretches across its anterior ring while holding the dens against the anterior arch. A synovial cavity is located between the dens and the transverse process. This ligament allows for rotation of the atlas on the dens and is responsible for stabilizing the cervical spine during flexion, extension, and lateral bending. The transverse ligament is the most important ligament in preventing abnormal anterior translation 36.

The alar ligaments run from the lateral aspects of the dens to the ipsilateral medial occipital condyles and to the ipsilateral atlas. The alar ligaments limit axial rotation and side bending. If the alar ligaments are damaged, as in a whiplash injury, the joint complex becomes hypermobile, which can lead to kinking of the vertebral arteries and stimulation of the nociceptors and mechanoreceptors. This may be associated with the typical complaints of patients with whiplash injuries such as headache, neck pain, and dizziness. The alar ligaments prevent excessive lateral and rotational motions, while allowing flexion and extension.

The anterior longitudinal ligament and the posterior longitudinal ligament are the major stabilizers of the intervertebral joints. Both ligaments are found throughout the entire length of the spine; however, the anterior longitudinal ligament is closely adhered to the discs in comparison to the posterior longitudinal ligament, and it is not well developed in the cervical spine. The anterior longitudinal ligament becomes the anterior atlantooccipital membrane at the level of the atlas, whereas the posterior longitudinal ligament merges with the tectorial membrane. Both ligaments continue onto the occiput. The posterior longitudinal ligament prevents excessive flexion and distraction 37.

The supraspinous ligament, interspinous ligament, and ligamentum flavum maintain stability between the vertebral arches. The supraspinous ligament runs along the tips of the spinous processes, the interspinous ligament runs between the spinous processes, and the ligamentum flavum runs from the anterior surface of the cephalad vertebra to the posterior surface of the caudad vertebra. The interspinous ligament and especially the ligamentum flavum control for excessive flexion and anterior translation 37. The ligamentum flavum also connects to and reinforces the facet joint capsules on the ventral aspect. The ligamentum nuchae is the cephalad continuation of the supraspinous ligament and has a prominent role in stabilizing the cervical spine.

Figure 1. Cervical spine

Figure 2. Cervical disc

Figure 3. Cervical facet joint (cervical zygapophyseal joint)

How do I know if I have whiplash?

Sometimes you can have no symptoms after a whiplash injury, but sometimes your symptoms can be severe. Pain from a whiplash injury often begins 6 to 12 hours after the injury. You may just feel uncomfortable on the day of the injury or accident and find that your pain, swelling and bruising increase over the following days.

Common symptoms of whiplash include:

- neck problems: pain, stiffness, swelling or tenderness

- difficulty moving your neck

- headaches, difficulty concentrating

- muscle spasms or weakness

- ‘pins and needles’, numbness or pain in your arms and hands or shoulders

- dizziness, vertigo, (a feeling you are moving or spinning) or tinnitus (ringing in your ears)

- difficulties swallowing or blurred vision

Your symptoms are likely to greatly improve or disappear within a few days to weeks. It may take longer for your symptoms to resolve completely and you might even experience some pain and neck stiffness for months after a whiplash injury.

How long does whiplash last?

Pain from a whiplash injury often begins 6 to 12 hours after the injury. Many people feel uncomfortable on the day of the injury or accident and find that pain, swelling and bruising increase over the following days.

Many people recover within a few days or weeks. For others it may take several months but sometimes it can last up to a year or more to experience substantial improvement in symptoms. Ongoing symptoms may vary in their intensity during the recovery period. This is normal.

You should see a doctor if you have had a motor vehicle accident or an injury that’s causing pain and stiffness in your neck.

The length of time it takes to recover from whiplash can vary and is very hard to predict.

Many people will feel better within a few weeks or months, but sometimes it can last up to a year or more.

Severe or prolonged pain can make it difficult to carry out daily activities and enjoy your leisure time. It may also cause problems at work and could lead to anxiety or depression.

Try to remain positive and focus on your treatment objectives. But if you do feel depressed, speak to your doctor about appropriate treatment and support.

What can I do to help my recovery?

Research has shown that it is better to try to keep doing normal daily activities as much as possible to aid recovery.

You need to take care of your neck and not expose it to unnecessary strain during the healing phase. It’s also important to regularly exercise your neck muscles. This booklet offers advice on how to care for your neck and suggests some specific exercises for your neck to help recovery.

Can I do the same activities as before?

Are there any limitations?

In the early stages of recovery, you may need to adapt some activities to care for your neck. However you should gradually resume normal activity as your neck improves (work, recreation and social).

Those who continue to work, even in a reduced capacity at first, have been shown to have a better recovery than people who take a long time off work.

An injury will cause pain. However the pain that occurs in the recovery period does not automatically mean that there is further injury. It is best to stay active and gently exercise to recover.

It may be necessary to limit some of your usual work and recreational activities in the early to mid-stage of recovery. Be adaptable – find new ways to do tasks to avoid unnecessary strain on your neck.

Whiplash causes

Whiplash injuries are commonly caused by car accidents. Whiplash can occur if your head is thrown forwards, backwards or sideways violently. For example if your neck is quickly accelerated and decelerated in a rear-end or side impact.

Common causes of whiplash include:

- road traffic accidents and collisions

- a sudden blow to the head – for example, during sports such as boxing or rugby

- a slip or fall where the head is suddenly jolted backwards

- being struck on the head by a heavy or solid object

- physical abuse or assault. Whiplash can occur if you are punched or shaken. It’s one of the injuries seen in shaken baby syndrome.

Studies with cadavers have shown the whiplash injury is the formation of the S-shaped curvature of the cervical spine which induced hyperextension on the lower end of the spine and flexion of the upper levels, which exceeds the physiologic limits of spinal mobility 38. The Quebec task force (QTF) defined whiplash as bony or soft tissue injuries as a result of rear-end or side-impact in road traffic accidents, and from other injuries resulting in “an acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer to the cervical spine” 5. The Quebec task force proposed a classification system to define the severity of the whiplash injury. In Grade 1 the patient complains of neck pain, stiffness, or tenderness with no positive findings on physical exam. In Grade 2 the patient exhibits musculoskeletal signs including decreased range of motion and point tenderness. In Grade 3 the patient also shows neurologic signs that may include sensory deficits, decreased deep tendon reflexes, muscle weakness. Grade 4 the patient shows a fracture 5. Most whiplash-associated disorders are considered to be minor soft tissue-based injuries without evidence of fracture.

Whiplash signs and symptoms

The symptoms of Whiplash Injury often include pain, decreased mobility of the neck, tenderness, headaches and problems of concentration and memory.

Common symptoms of whiplash include:

- neck pain and stiffness

- swelling and tenderness in the neck

- temporary loss of movement, or reduced movement, in the neck

- headaches, most often starting at the base of the skull

- muscle spasms

- tenderness or pain in shoulder, upper back or arms

- tingling or numbness in the arms

- fatigue

- pain in the shoulders or arms.

Whiplash can also cause:

- lower back pain

- pins and needles, numbness or pain in the arms and hands (paresthesias)

- dizziness

- sleep disturbances

- tiredness and irritability

- difficulties swallowing (dysphasia)

- temporomandibular joint symptoms

- blurred vision

- memory problems

- vertigo (a feeling you are moving or spinning)

- difficulty concentrating

- irritability

- tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

Psychosocial symptoms 39:

- depression

- anger

- frustration

- anxiety

- family stress

- occupational stress

- hypochondriasis (also known as health anxiety or illness anxiety disorder)

- compensation neurosis

- drug dependency

- post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD)

- litigation

- social isolation

You should see a doctor if you have neck pain after a car accident or after an injury.

Pain

Whiplash injury is a painful injury. As a result of the impact that caused the injury, there may be bruising or tearing of the soft tissues in the neck region, contributing to symptoms of pain. The pain of whiplash might be localized in the neck, or may also extend to the shoulders, and upper arms. Many individuals who have sustained whiplash injuries also report pain in the lower back region.

Decreased Mobility of the Neck

The uninjured neck has considerable mobility in several directions. The neck can move up and down (flexion-extension), side to side (lateral flexion) and can rotate (rotation). These movements are often restricted following a whiplash injury. There is a natural tendency for muscles to contract when the neck is painful. This contraction is the body’s way of trying to protect itself against further injury.

Tenderness of the Injured Area

Whiplash injury is considered to be an ‘overload’ injury. As a function of the excessive forces that impacted on the neck in the motor vehicle crash, elongation, bruising or tearing of the soft tissue can occur. In turn, the soft-tissue injuries can lead to inflammation and edema (e.g., swelling). Inflamed and swollen tissues are more ‘tender’ in that they are more sensitive to touch. Following a whiplash injury, areas of tenderness can include regions of the neck, shoulders and upper arms.

Headaches

Whiplash injury can also cause headaches. Headaches of whiplash injury may differ from tension or migraine headaches. Whiplash headaches, are more likely to occur at the top or the back of the head as opposed to regions around the eyes or the side of the head. Whiplash headaches can be intermittent or constant.

Memory and Concentration Problems

Individuals who have sustained whiplash injuries sometimes report problems with memory and concentration. If the head was struck during the crash that caused the whiplash injury, it is possible that the memory or concentration problems might be due to concussion. If the head was not struck, the memory and concentration problems are most likely due to the distracting effects of pain or anxiety.

Long term effects of whiplash

Most people who have whiplash injury feel better within a few weeks and don’t seem to have any lasting effects from the injury. However, some people continue to have pain for several months or years after the whiplash injury occurred.

It is difficult to predict how each person with whiplash may recover. In general, you may be more likely to have chronic pain if your first symptoms were intense, started rapidly and included:

- Severe neck pain

- More-limited range of motion

- Pain that spread to the arms

The following risk factors have been linked to a worse outcome:

- Having had whiplash before

- Older age

- Existing low back or neck pain

- A high-speed injury

Whiplash is an injury from which most individuals recover well. Studies have shown that people who are positive about recovery and resume their normal daily activities as tolerated may recover faster than those who markedly alter or markedly reduce their activity level for a period.

A small percentage of people who have a whiplash injury may develop long-term neck pain. Research is being conducted worldwide to understand why there are different recovery rates between different people. Some reasons have been identified such as age and initial severity of the pain or injury. However there is still more to be learnt.

The main symptoms of a whiplash associated disorder are neck pain and stiffness. Other symptoms such as headaches, aching in the arms or feelings of being lightheaded are common.

Symptoms may appear immediately after the incident or have a delayed onset of a few hours or days. The nature of injury and the number and severity of symptoms vary between different people.

Neck x-rays may be taken to rule out injuries such as bone fractures or dislocations. X-ray reports often state that no abnormality has been found. However, x-rays do not reveal injuries to the soft tissues of the neck (non bony parts of joints, ligaments, muscles) and x-rays do not provide information about pain levels. Normal x-rays only provide assurance that there are no major bone injuries.

Whiplash injury diagnosis

Questions about the event and your symptoms are the doctor’s first step for making a diagnosis. You also may be asked to fill out a brief form that can help your doctor understand the frequency and severity of your symptoms, as well as your ability to do normal daily tasks.

Examination

During the exam your doctor will need to touch and move your head, neck and arms. He or she will also ask you to move and perform simple tasks. This examination helps your doctor determine:

- The range of motion in your neck and shoulders

- The degree of motion that causes pain or an increase in pain

- Tenderness in the neck, shoulders or back

- Reflexes, strength and sensation in your limbs

Imaging tests

Your doctor will likely order one or more imaging tests to rule out other conditions that could be causing or contributing to neck pain. These include the following tests:

- X-rays of the neck. X-rays of the neck taken from multiple angles can identify fractures, dislocations or arthritis.

- Computerized tomography (CT). Computerized tomography (CT) is a specialized X-ray technology that can produce multiple cross-sectional images of bone and reveal details of possible bone damage.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a technology that uses radio waves and a magnetic field to produce detailed 3-D images. In addition to bone injuries, MRI scans can detect some soft tissue injuries, such as damage to the spinal cord, disks or ligaments.

Imaging techniques (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging or computerized tomography) and physiological methods are often unable to provide useful and unequivocal information in the instances of mild injuries 40. In the past, the suggestion was to combine various investigation methods, such as imaging techniques and psychiatric, orthopedic, and neurological data, together with a detailed clinical history and evaluation, to draw a complete diagnostic picture of a patient and a realistic level of disability 40. However, this kind of assessment is costly in terms of time and expenses related to the instruments, it requires the presence of specialists 40, and, most importantly, does not necessarily exclude the presence of exaggerated symptoms.

Whiplash treatment

It is important to note that, although there are many different treatment options available for the management of whiplash injury, not all have been shown to be effective. It is also important to note that even though a certain treatment might have been shown to be effective, it might not be the right treatment for you.

The goals of whiplash treatment are to:

- Control pain

- Restore normal range of motion in your neck

- Get you back to your normal activities

It is best to have an in-depth discussion with your doctor, chiropractor or physiotherapist to determine the best treatments for the symptoms you are experiencing.

Your treatment plan will depend on the extent of your whiplash injury. Some people only need over-the-counter pain medication or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), a cervical collar, and at-home care. Others may need prescription medication (antidepressants, muscle relaxants) and specialized pain treatment in conjunction with physiotherapy or chiropractic care.

Soft foam cervical collars were once commonly used for whiplash injuries to hold the neck and head still. However, studies have shown that keeping the neck still for long periods of time can decrease muscle strength and interfere with recovery 41, 42, 43. Still, using of a cervical collar to limit movement may help reduce pain soon after your injury, and may help you sleep at night. Recommendations for using a cervical collar vary though. Some experts suggest limiting cervical collar use to no more than 72 hours, while others say it may be worn up to three hours a day for a few weeks. Your doctor can instruct you on how to properly use the cervical collar, and for how long.

Pain management

Your doctor may recommend one or more of the following treatments to lessen pain 44:

- Rest. Rest may be helpful during the first 24 hours after injury, but prolonged bed rest may delay recovery.

- Ice or heat. Apply ice or heat to the neck for 15 minutes up to six times a day.

- Over-the-counter pain medications. Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) and ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), often can control mild to moderate whiplash pain.

- Prescription painkillers. People with more-severe pain may benefit from short-term treatment with prescription pain relievers.

- Muscle relaxants. These drugs may control pain and help restore normal sleep if pain prevents you from sleeping well at night.

- Injections. An injection of lidocaine (Xylocaine) — a numbing medicine — into painful muscle areas may be used to decrease pain so that you can do physical therapy.

Individuals at high-risk of non-recovery should receive referral to a specialist clinician with expertise in the management of whiplash associated disorder 45, 6.

How to treat whiplash

A number of treatments have been developed to manage the symptoms of whiplash injury. Some of the more common treatments described below include 46:

- Advice to remain active

- Education

- Medication

- Physiotherapy

- Treatment of Mental Health Problems

Advice to Remain Active

Many doctor’s and physiotherapists will recommend to their patients that they try to remain as active as possible during the recovery period. While such advice might not appear to be much of a treatment, the advice is nevertheless a critical element in ensuring optimum recovery.

When people are injured and are experiencing pain and discomfort, there is a tendency to reduce one’s participation in important activities of daily life. As a result of pain or discomfort, individuals might reduce their participation in family or home activities, in recreational activities and individuals might also discontinue their occupational activities.

Reducing activity sometimes feels like the right thing to do because it is associated with a reduction in pain. But there lies the trap. Activity reduction is probably the worst thing to do in the management of a whiplash injury. While activity reduction might reduce pain and discomfort in the short term, in the long term, activity reduction will likely lead to more severe pain, and more severe disability.

Muscles need to move to remain healthy. Individuals who discontinue the important activities of their daily lives, or individuals who spend excessive time resting or lying down will actually recover more slowly. Slowing down a little bit makes sense during the initial days of recovery, but lying down or bed rest should be avoided. Remaining active is the best formula for optimal recovery.

Medication

The two most frequently prescribed medications for whiplash injury are anti-inflammatories and painkillers 47. Following a whiplash injury, the soft-tissues of the neck and shoulders can become inflamed. Inflammation often leads to increased stiffness and pain. Anti-inflammatories reduce swelling of the injured soft tissues, and reduce pain as well. Inflammation is typically only present in the first few weeks following injury so anti-inflammatories tend not be used for long term pain management.

There are two main types of painkillers (analgesics) that might be prescribed for pain caused by whiplash injury. There are non-steroidal analgesics such as aspirin or paracetamol (acetaminophen), and there are opiate analgesics such as codeine. Painkillers can be useful treatments to manage the pain of whiplash injury in the short term, but long-term use is typically not recommended. Long-term use of acetaminophen (paracetamol) can cause stress on liver function. Long-term use of opiate analgesics can lead to gastro-intestinal problems, and of even more concern, these medications can lead to problems of addiction.

Education

It is becoming increasingly clear that education is an important element of the management of whiplash injury. A doctor or a physiotherapist might choose to spend some time explaining to a patient exactly what whiplash is and describe the pros and cons of different treatments.

One of the benefits of education is that it can help reduce anxiety. The experience of severe pain and symptoms of stiffness and headaches can be alarming. The injured person might think, ‘there must be something seriously wrong with my neck’, ‘if it hurts this much, there must be a lot of damage’, ‘when I move, it hurts more, so I should probably not move’. Thoughts like these will create anxiety or fear. In turn, anxiety and fear will lead the person to discontinue even more of their activities.

The doctor or physiotherapist might wish to educate the injured person about why he or she is experiencing a lot of pain, to explain that the symptoms of whiplash will recover over time, and to explain the importance of remaining as active as possible.

The doctor or physiotherapist might also wish to educate the injured person about the relation between pain and injury severity. We often assume that if the pain is severe, this must mean that the injury is severe. But with whiplash injury that is not the case. The pain of whiplash can be very severe, but that does not mean that severe or irreparable damage has been done to the neck. The majority of whiplash injuries are not considered ‘medically serious’; the pain might be initially severe, but the pain dissipates over time.

Exercise

Your doctor will likely prescribe a series of stretching and movement exercises for you to do at home. These exercises can help restore range of motion in your neck and get you back to your normal activities 48, 49, 50. Applying moist heat to the painful area or taking a warm shower may be recommended before exercise.

Exercises may include (see more below):

- Rotating your neck in both directions

- Tilting your head side to side

- Bending your neck toward your chest

- Rolling your shoulders

Physical therapy

Physical therapy is another commonly used approach to treating whiplash injury. If you have ongoing whiplash pain or need assistance with range-of-motion exercises, your doctor may recommend that you see a physical therapist. A physical therapist might use a variety of treatment techniques to manage the symptoms of whiplash. Initially, the physiotherapist might use modalities such as manual therapy or ice to reduce the swelling and inflammation of the injured areas. The physical therapist will also provide the injured person with exercises to improve or maintain the movement in their neck as well as strength and control of the muscles in their neck and upper body and to restore normal movement. This in turn will help increase the person’s tolerance for participation in household, recreational and occupational activities.

As the injured person begins to be more physically active, it sometimes happens that their pain and discomfort might increase. This increase in pain is usually caused by engaging muscles that have remained inactive or immobile for extended periods of time. The pain associated with increasing activity is temporary and will usually subside in a day or two.

In some cases, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) may be used. TENS applies a mild electric current to the skin. Limited research suggests this treatment may temporarily ease neck pain and improve muscle strength.

The number of physical therapy sessions needed will vary from person to person. Your physical therapist can also create a personalized exercise routine that you can do at home.

Treatment of Mental Well Being

Some individuals with whiplash injuries might develop symptoms of a mental health problem. The most common mental health problems associated with whiplash injury include depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress symptoms. If an injured person is experiencing troubling symptoms of depression, anxiety or post-traumatic symptoms, the doctor might consider prescribing medication such as an anti-depressant or anti-anxiety medication. Since the presence of symptoms of a mental health problem can slow the rate of recovery following whiplash injury, these medications can play an important role in the successful management of whiplash injury.

If you have developed symptoms of a mental health problem following your whiplash injury, your doctor might also consider a referral to a mental health professional such as a psychologist or a social worker. Psychologists and social workers can provide counselling or psychotherapy that can be useful in managing some of the mental health consequences of whiplash injury. Your doctor can familiarize you with the mental health services that are available in your community.

Alternative medicine

There are many other types of treatments that have been tried to treat whiplash pain, but research about how well they work is limited 51, 52, 53, 54, 55. Some of these include manipulation, acupuncture, electrical nerve stimulation, traction, biofeedback, ultrasound among many others 56, 57.

- Acupuncture. Acupuncture involves inserting ultrafine needles through specific areas on your skin. It may offer some relief from neck pain.

- Chiropractic care. A chiropractor performs joint manipulation techniques. There is some evidence that chiropractic care may provide pain relief when paired with exercise or physical therapy.

- Neck massage. Neck massage may provide short-term relief of neck pain from whiplash injury.

- Mind-body therapies. Exercises that incorporate gentle movements and a focus on breathing and mindfulness, such as tai chi, qi gong and yoga, may help ease pain and stiffness.

It is difficult to make strong statements about the utility of these treatments since so little research has examined whether they are effective. Injured individuals who are slow to recover might reach a level of desperation where they are willing to try anything. It is important to remember that unless a treatment has been shown to be effective in a clinical trial, there is always the possibility that the treatment might not be helpful, or could actually worsen the condition. Before starting any treatment for your whiplash injury, it is best to discuss with a doctor or medical specialist the treatment options that are most appropriate for your condition.

Home remedies for whiplash injury

You are your own best resource in the recovery process. Managing yourself is a key part to stopping the discomfort that you are experiencing. Staying active is important. Do as many of your normal activities as possible. Some more vigorous activities that place undue stresses on your neck may need to be avoided in the early stages of recovery.

However, better recovery has been found in individuals who continue a healthy active routine after a whiplash injury. This goes for your general health as well as that of your neck.

Plan gradual increases in activity and exercise levels so that you can successfully return to full participation in your regular activities, hobbies or sports.

Continue or resume working

Those who continue to work, even in a reduced capacity at first, have been shown to have a better recovery than people who take a long time off work. It may be necessary to change some work routines for a while.

You may wish to talk to your employer or health care practitioner regarding ways to modify your particular work tasks and environment if difficulties continue.

Keeping a good relationship with your employer and co-workers is helpful in the recovery process. Talk to your employer openly and frequently.

During times of high work load or busy periods, it is important to let colleagues and supervisors know that you may need extra time or help to meet deadlines. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. You may be in a position to return the favor at some time.

Maintain the flexibility and muscle support of your neck

An exercise program that is specific to the neck and upper back will greatly benefit your recovery. The exercise program in this booklet will help you regain normal neck movement and function.

The exercises are also designed to ensure that your neck receives proper support from the muscles.

Perform daily activities in a strain-free way

Thinking about how you do your work and recreational activities can avoid unnecessary strain on your neck, reduce pain and positively assist recovery.

Be aware of neck positions and postures at work and home

Keeping your spine in a good position is important in everyday activities as well as during the exercises.

The positions in which you work and relax each day have a great impact on the health of your spine. It is easy to compensate and allow yourself to develop poor postural habits. You will need to be consciously aware of postures and positions when you are performing tasks at home and work.

Postural correction exercise

Correct your posture by gently growing tall from the lower back and pelvic region (see Figure 1 below).

Gently raise your pelvis up out of a slumped position.

Next, reposition your shoulder blades so they draw back and across your rib cage (towards the center of your spine). This needs only minimal effort.

Gently lift the base of your skull off the top of your neck. This takes the weight of your head off your neck and stimulates the muscles to work.

Hold the position for at least 10 seconds. Repeat frequently during the day (e.g. three or four times an hour).

Perform this exercise when sitting, standing or while walking, at work and at home.

Figure 4. Whiplash injury exercises

Range of motion exercises

For each of the following exercises, complete 5-10 repetitions in each direction.

Neck rotation exercise

Assume the correct postural position. Gently turn your head to the left, looking where you are going to see over your shoulder as much as possible.

You may find it easier to have a target on the wall to focus on.

With each repetition, try to go a little further in that direction. Perform the same exercise to the right side.

Figure 5. Neck rotation exercise

Neck side bending exercise

Assume the correct postural position. Start with your head centered and gently bring your right ear down towards your right shoulder. You may feel a normal stretch of the muscles on the side of your neck. The exercise should be pain-free. Perform this exercise on the left side.

Figure 6. Neck side bending exercise

Forward and backward bending

Assume the correct postural position.

Figure 7. Neck forward and backward bending exercise

Exercises to retrain muscle control

Head nod and holding exercise

This is an important exercise to retrain the deep neck muscles of the front of your neck for pain relief and muscle control.

Lie on your back with knees bent without a pillow under your head and neck.

A. If this is not comfortable, place a small, folded towel under your head for support.

B. Start by looking up at a point on the ceiling. Then with your eyes, look at a spot on the wall just above your knees. Feel the back of your head slide up the bed as you perform a slow and gentle nod as if you were indicating ‘yes’.

While doing the exercise, place your hand gently on the front of the neck to feel the superficial muscles. Make sure they stay soft and relaxed when doing the head nod movement. Stop at the point you sense the muscles are beginning to harden, but keep looking down with your eyes.

Hold the position for 10 seconds and then relax. Look up to a point on the ceiling to resume the starting position. Repeat the exercise 10 times.

Figure 8. Head nod and holding exercise

Head and neck exercises

These are important exercises to retrain the muscles at the back of your neck for pain relief and muscle control. There are three exercises to perform, which ensures you exercise the upper and lower regions of your neck.

Lie on your stomach, propped up on your elbows. Push through your elbows to prevent your chest from sagging between your shoulder blades.

To begin, perform each exercise five times as one set. Try to build up to three sets (and eventually three sets of 10 repetitions each). Remember to keep pushing through your elbows to keep your chest raised for the whole set. Have a rest between sets.

Figure 9. Head and neck exercises

Shoulder blade exercises

Poor muscle control around the shoulder blades can increase pain and strain on the neck. There are three exercises that you can do for your shoulder blades and arms.

This first exercise will relax and ease any tension in the muscles on top of your shoulders. It can give you pain relief.

Figure 10. Shoulder blade exercises

The second exercise helps you to improve the control of your shoulder blades while mimicking work you may do with your arms. It trains you to ease any tension in the muscles on top of your shoulders while you are using your arms.

Sit and correct your posture and draw your shoulder blades back and across your rib cage as you have already practised.

Concentrate on holding your shoulder blade position. Then move your arms:

- (A) forwards and backwards;

- (B) out to the side; and

- (C) turn your forearms outwards.

Do not lift your arms more than 30 degrees in exercises A and B (that is, about a quarter of the way up). Perform each exercise (A,B and C) five times and repeat this set three times.

When you feel confident that you can do the exercise keeping your shoulder blades gently back, hold a 250 gram can in each hand as a small weight.

Figure 11. Shoulder blade exercises part 2

The third exercise is simply raising alternate arms forward as far up as you can go. Make sure that you maintain a good posture, especially concentrating on lifting the base of your skull off the top of your neck and then as you raise your arm, keep your thumb facing upwards. Perform three sets of five left and right arm raises.

Figure 12. Shoulder blade exercises part 3

Neck isometric exercise (no movement)

Assume the correct postural position and gently raise the back of your head. Place your right hand on the right cheek. Without moving your head, turn your eyes to the right and gently push your head into your hand as if to look over your shoulder. While performing this exercise no movement occurs. Hold the muscle contraction for five seconds.

Do the exercise smoothly and gently, use only 10% effort.

Change hand position and perform the same exercise to the left side. Do five repetitions on each side.

Figure 13. Neck isometric exercise

Once your neck pain has settled, the exercises can be progressed to include strengthening exercises.

These exercises should not cause pain. Progress slowly.

Head lift exercise

The weight of your head is enough weight to lift. Start by sitting on a chair close to a wall. Rest your head back on the wall.

Slide the back of your head up the wall to nod your chin and hold it in this position. Then just take the weight of your head off the wall (your hair still touches the wall). Hold for five seconds and relax.

Start by doing three sets of two to three repetitions and gradually build up to three sets of five repetitions.

Shifting the chair a little further from the wall makes the exercise more difficult.

You can progress the exercise by moving the chair away from the wall in five centimeter stages.

Progression: Lie resting your head on two pillows.

Slide the back of your head up the pillow to nod your chin and hold it in this position. Then try to just lift the weight of your head until it just clears the pillow.

Hold for five seconds and relax. Start by doing three sets of two to three repetitions and gradually build up to three sets of five repetitions.

The exercise can be progressed by removing one pillow and performing the exercise in the same way.

Figure 15. Head lift exercise (progression)

Sitting

Sitting in one position for prolonged periods is not good for anyone, certainly not someone with neck pain.

Change your position

Sitting in one position for prolonged periods is not good for anyone, certainly not someone with neck pain. Keep your neck healthy and move often.

It is essential that you change your position before your neck becomes stiff or sore. Perform the postural correction exercise regularly. Stand up and move regularly, at least every hour.

Assess how you spend your day at work

Whether sitting in a motor vehicle, at a desk or computer terminal, you need to give your body a regular change of position throughout the day. Take a ‘neck break’, it can be as simple as standing up for a few moments to straighten your spine. Stand and stretch backwards gently to reverse the flexed sitting posture. A complete change of position every hour is advisable.

Working at a computer

Arrange your desk, chair and computer to avoid strain on your neck (see Figure 2). Have work materials close to you and in easy reach.

- A. Position the top of your screen slightly below eye level and directly in front of you (50-70cm or arm’s length away). There is no single monitor height suitable for everyone. Position the screen to have a comfortable viewing angle to the middle of the screen. Avoid extremes of head and neck bending (upwards or downwards).

- B. Have an adjustable chair so that you can change the height and angle of the back support. Have the chair close to the desk so you do not have to reach for the keyboard or mouse. If possible, rest your forearms on the desktop to ‘unload’ the shoulders.

- C. Desk height should allow sitting with shoulders and arms relaxed with elbows at a 90 degree angle and wrists in a neutral position. Sit with hips and knees at close to 90 degree angles. Feet should be flat on the floor or use a foot stool to achieve a comfortable position.

- D. If working from documents for prolonged periods, these should be placed on a document holder either positioned between the keyboard and monitor or at the same eye level as the screen and close to the monitor. Reading from items placed flat on the desktop may increase the strain on your neck and should be avoided. Books and documents should be elevated onto a sloped surface (e.g. an empty 2-ring folder).

- E. When using the computer mouse, keep the mouse close to the keyboard, use keyboard shortcuts instead of the mouse and alternate which hand uses the mouse.

Current research suggests that spending time standing at work (high set work station) has benefits not only for the neck and back, but also for general health (e.g. by increasing daily activity levels to help maintain healthy body weight). At home and work, try to spend time working in a standing position.

Figure 16. Working at a computer

Whiplash prognosis

Most people with whiplash get better within a few weeks by following a treatment plan that includes pain medication and exercise. However, some people have chronic neck pain and other long-lasting complications. Recovery following whiplash injury, if it is to occur, will occur for the most part within the first 3 months post injury 17. Current estimates suggest that approximately 50% of individuals will recover by 3 months post injury, whilst the remainder will experience mild to moderate long-term disability 18, 19, 20.

Whiplash prognosis varies secondary to comorbidities prior to the injury, severity of whiplash-associated disorders, age, the legal environment and socioeconomic environment 8. Full recovery has been shown to occur in a few days to several weeks 58. However, disability can be permanent and range from chronic pain to impaired physical function 58. There have been inadequate studies that incorporate mitigating factors, such as socioeconomic and legal, which can impact an accurate assessment of recovery 8. Legal environment, prior injury, comorbidity, age, and defensive medicine all play roles in the management and outcomes 58. In countries where there is little or no litigation, whiplash prognosis is more favorable lending that economic gain for disability may play a role in determining the patient’s reports of full recovery 58. For example, in countries such as Lithuania and Greece, where there is no compensation culture and no formal compensation system for late whiplash-related injuries, the development of chronic symptoms following whiplash is a rare phenomenon 23, 24. This evidence suggests that the culture and expectations around whiplash, local insurance systems, and the prospect of monetary benefits are likely to play important roles in the prevalence of whiplash injuries and related claims, as well as in the recovery process 25. In Germany, for instance, whiplash-associated disorders represent the most common consequence of road traffic accidents, counting approximately 20,000 cases each year and costing insurance companies more than 500 million euro annually 24. Similarly, in Italy, it is estimated that the compensation for whiplash-related damages amounts to more than 2 million euro every year 59.

- Godek P. Whiplash Injuries. Current State of Knowledge. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2020 Oct 31;22(5):293-302. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0014.4210[↩]

- Aarnio M, Fredrikson M, Lampa E, Sörensen J, Gordh T, Linnman C. Whiplash injuries associated with experienced pain and disability can be visualized with [11C]-D-deprenyl positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Pain. 2022 Mar 1;163(3):489-495. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002381[↩]

- Eck JC, Hodges SD, Humphreys SC. Whiplash: a review of a commonly misunderstood injury. Am J Med. 2001 Jun 1;110(8):651-6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00680-5[↩]

- Ferrari R. Whiplash–review of a commonly misunderstood injury. Am J Med. 2002 Feb 1;112(2):162-3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00953-6.[↩]

- Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, Cassidy JD, Duranceau J, Suissa S, Zeiss E. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 Apr 15;20(8 Suppl):1S-73S. Erratum in: Spine 1995 Nov 1;20(21):2372.[↩][↩][↩]

- Griffin A, Jagnoor J, Arora M, Cameron ID, Kifley A, Sterling M, Kenardy J, Rebbeck T. Evidence-based care in high- and low-risk groups following whiplash injury: a multi-centre inception cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Nov 6;19(1):806. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4623-y[↩][↩]

- Evans, R.W. (2010), Persistent Post-Traumatic Headache, Postconcussion Syndrome, and Whiplash Injuries: The Evidence for a Non-Traumatic Basis With an Historical Review. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 50: 716-724. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01645.x[↩]

- Bragg KJ, Varacallo M. Cervical Sprain. [Updated 2022 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541016[↩][↩][↩]

- Toney-Butler TJ, Varacallo M. Motor Vehicle Collisions. [Updated 2022 Aug 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441955[↩]

- Chappuis G, Soltermann B; CEA; AREDOC; CEREDOC. Number and cost of claims linked to minor cervical trauma in Europe: results from the comparative study by CEA, AREDOC and CEREDOC. Eur Spine J. 2008 Oct;17(10):1350-7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0732-8[↩]

- Martin JL, Perez K, Mari-Dell’olmo M, Chiron M. Whiplash risk estimation based on linked hospital-police road crash data from France and Spain. Inj Prev. 2008;14:185–190. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016600[↩]

- Ye S, Chen Q, Liu N, Chen R, Wu Y. Citation analysis of the most influential publications on whiplash injury: A STROBE-compliant study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Sep 30;101(39):e30850. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000030850[↩]

- Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, van der Velde G, Holm LW, Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Peloso PM, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, Nordin M, Haldeman S; Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 Feb 15;33(4 Suppl):S93-100. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816445d4[↩]

- Sterling M, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, Kamper SJ, Stemper B. Prognosis after whiplash injury: where to from here? Discussion paper 4. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 Dec 1;36(25 Suppl):S330-4. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182388523[↩]

- Al-Khazali HM, Ashina H, Iljazi A, Lipton RB, Ashina M, Ashina S, Schytz HW. Neck pain and headache after whiplash injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2020 May;161(5):880-888. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001805[↩][↩]

- Schofferman J, Bogduk N, Slosar P. Chronic whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders: an evidence-based approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007 Oct;15(10):596-606. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200710000-00004[↩]

- Kamper SJ, Rebbeck TJ, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M. Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2008;138(3):617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.019[↩][↩]

- Sterling M, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J. Compensation claim lodgement and health outcome developmental trajectories following whiplash injury: A prospective study. Pain. 2010 Jul;150(1):22-28. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.013[↩][↩]

- Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, van der Velde G, Holm LW, Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Peloso PM, Cassidy JD, Guzman J, Nordin M, Haldeman S. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 Feb;32(2 Suppl):S108-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.015[↩][↩]

- Kamper SJ, Rebbeck TJ, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M. Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2008 Sep 15;138(3):617-629. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.019[↩][↩][↩]

- Linnman C, Appel L, Furmark T, Söderlund A, Gordh T, Långström B, Fredrikson M. Ventromedial prefrontal neurokinin 1 receptor availability is reduced in chronic pain. Pain. 2010 Apr;149(1):64-70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.01.008[↩]

- Linnman, C., Appel, L., Söderlund, A., Frans, Ö., Engler, H., Furmark, T., Gordh, T., Långström, B. and Fredrikson, M. (2009), Chronic whiplash symptoms are related to altered regional cerebral blood flow in the resting state. European Journal of Pain, 13: 65-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.03.001[↩]

- Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Nygren Å. Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1179–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421606[↩][↩]

- Noll-Hussong M. Whiplash Syndrome Reloaded: Digital Echoes of Whiplash Syndrome in the European Internet Search Engine Context. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3:e15. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7054[↩][↩][↩]

- Monaro M, Bertomeu CB, Zecchinato F, Fietta V, Sartori G, De Rosario Martínez H. The detection of malingering in whiplash-related injuries: a targeted literature review of the available strategies. Int J Legal Med. 2021 Sep;135(5):2017-2032. doi: 10.1007/s00414-021-02589-w[↩][↩]

- Sterling M. Clinical presentation of whiplash associated disorders. In: Sterling M, Kenardy J, editors. Whiplash: evidence base for clinical practice. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier Australia; 2011. pp. 9–15.[↩]

- Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Nygren A. Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med. 2000 Apr 20;342(16):1179-86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004203421606[↩]

- Cassidy JD, Leth-Petersen S, Rotger GP. What happens when compensation for whiplash claims is made more generous? J Risk Insur. 2018;85:635–662. doi: 10.1111/jori.12169[↩]

- Johnson R. Anatomy of the cervical spine and its related structures. Torg JS, ed. Athletic Injuries to the Head, Neck, and Face. 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book; 1991. 371-83.[↩]

- Parke WW, Sherk HH. Normal adult anatomy. Sherk HH, Dunn EJ, Eismon FJ, et al, eds. The Cervical Spine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott Co; 1989. 11-32.[↩]

- McLain RF. Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints. Spine. 1994 Mar 1. 19(5):495-501.[↩]

- Bogduk N, Twomey L. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.[↩][↩]

- Dreyfus P. The cervical spine: Non-surgical care Presented at: The Tom Landry Sports Medicine and Research Center; April 8, 1993; Dallas, Texas.[↩]

- Mendel T, Wink CS, Zimny ML. Neural elements in human cervical intervertebral discs. Spine. 1992 Feb. 17(2):132-5.[↩]

- Panjabi MM, Oxland TR, Parks EH. Quantitative anatomy of cervical spine ligaments. Part I. Upper cervical spine. J Spinal Disord. 1991 Sep. 4(3):270-6.[↩]

- Fielding JW, Cochran GB, Lawsing JF 3rd, Hohl M. Tears of the transverse ligament of the atlas. A clinical and biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974 Dec. 56(8):1683-91.[↩]

- Panjabi MM, Vasavada A, White A III. Cervical spine biomechanics. Semin Spine Surg. 1993. 5:10-6.[↩][↩]

- Chen HB, Yang KH, Wang ZG. Biomechanics of whiplash injury. Chin J Traumatol. 2009 Oct;12(5):305-14. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-1275.2009.05.011[↩]

- Ebell MH. Diagnosis: making the best use of medical data. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Mar 15;79(6):478-80. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2002/0201/p478.html[↩]

- Blakely TAB, Jr, Harrington DE. Mild head injury is not always mild; implications for damage litigation. Med Sci Law. 1993;33:231–242. doi: 10.1177/002580249303300309[↩][↩][↩]

- Gennis P, Miller L, Gallagher EJ, Giglio J, Carter W, Nathanson N. The effects of soft cervical collars on persistent neck pain in patients with whiplash injury. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(6):568–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03466.x[↩]

- Ricciardi L, Stifano V, D’Arrigo S, Polli FM, Olivi A, Sturiale CL. The role of non-rigid cervical collar in pain relief and functional restoration after whiplash injury: a systematic review and a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Spine J. 2019 Aug;28(8):1821-1828. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06035-9[↩]

- Hernández-Sousa MG, Sánchez-Avendaño ME, Solís-Rodríguez A, Yáñez-Estrada M. Incapacidad por esguince cervical I y II y el uso del collarín [Disability by cervical sprain I and II and the use of neck collar]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2013 Mar-Apr;51(2):182-7. Spanish.[↩]

- Peloso P, Gross A, Haines T, Trinh K, Goldsmith CH, Burnie S; Cervical Overview Group. Medicinal and injection therapies for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD000319. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000319.pub4. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5:CD000319.[↩]

- Bandong AN, Leaver A, Mackey M, Sterling M, Kelly J, Ritchie C, Rebbeck T. Referral to specialist physiotherapists in the management of whiplash associated disorders: Perspectives of healthcare practitioners. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018 Apr;34:14-26. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.11.006[↩]

- Ritchie C, Hollingworth SA, Warren J, Sterling M. Medicine use during acute and chronic postinjury periods in whiplash-injured individuals. Pain. 2019 Apr;160(4):844-851. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001460[↩]

- Binder AI. Neck pain. BMJ Clin Evid. 2008 Aug 4;2008:1103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2907992[↩]

- Ludvigsson ML, Peterson G, Dedering A, Peolsson A. One- and two-year follow-up of a randomized trial of neck-specific exercise with or without a behavioural approach compared with prescription of physical activity in chronic whiplash disorder. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(1):56–64. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2041[↩]

- Peterson G, Nilsson D, Trygg J, Peolsson A. Neck-specific exercise improves impaired interactions between ventral neck muscles in chronic whiplash: a randomized controlled ultrasound study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9649. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27685-7[↩]

- Peolsson A, Landen Ludvigsson M, Peterson G. Neck-specific exercises with internet-based support compared to neck-specific exercises at a physiotherapy clinic for chronic whiplash-associated disorders: study protocol of a randomized controlled multicentre trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):524. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1853-1[↩]

- Teasell RW, McClure JA, Walton D, Pretty J, Salter K, Meyer M, Sequeira K, Death B. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): part 3 – interventions for subacute WAD. Pain Res Manag. 2010 Sep-Oct;15(5):305-12. doi: 10.1155/2010/108685[↩]

- Aigner N, Fialka C, Radda C, Vecsei V. Adjuvant laser acupuncture in the treatment of whiplash injuries: a prospective, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118(3):95. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0530-4[↩]

- Brijnath B, Bunzli S, Xia T, et al. General practitioners knowledge and management of whiplash associated disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder: implications for patient care. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:82. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0491-2[↩]

- Borchgrevink GE, Kaasa A, McDonagh D, Stiles TC, Haraldseth O, Lereim I. Acute treatment of whiplash neck sprain injuries: a randomized trial of treatment during the first 14 days after a car accident. Spine. 1998;23(1):25–31. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801010-00006[↩]

- Teasell RW, McClure JA, Walton D, Pretty J, Salter K, Meyer M, Sequeira K, Death B. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): part 2 – interventions for acute WAD. Pain Res Manag. 2010 Sep-Oct;15(5):295-304. doi: 10.1155/2010/640164[↩]

- Gálvez-Hernández CL, Rodríguez-Ortiz MD, Del Río-Portilla Y. Retroalimentación biológica para pacientes con esguince cervical agudo [Biofeedback treatment for acute whiplash patients]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2016 Jul-Aug;54(4):480-9. Spanish.[↩]

- Ruiz-Molinero C, Jimenez-Rejano JJ, Chillon-Martinez R, Suarez-Serrano C, Rebollo-Roldan J, Perez-Cabezas V. Efficacy of therapeutic ultrasound in pain and joint mobility in whiplash traumatic acute and subacute phases. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014 Sep;40(9):2089-95. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.04.016[↩]

- Binder A. The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash. Eura Medicophys. 2007 Mar;43(1):79-89. https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/europa-medicophysica/article.php?cod=R33Y2007N01A0079[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Previtera AM (2004) Il colpo di frusta cervicale. Diagnosi, biomeccanica e trattamento. Grafica MA.RO Editrice S.r.l.[↩]