What is vas deferens

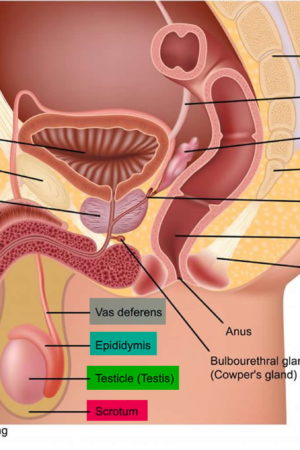

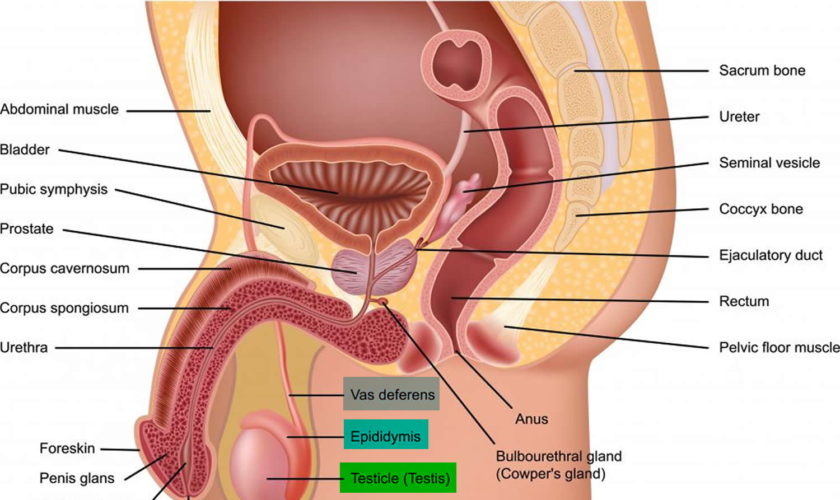

The vas deferens or the ductus deferens is a continuation of the duct of the epididymis (the spermatic cord). The term vasectomy, the surgical method of male contraception, consists of cutting out a short portion of the ductus deferens to interrupt the passage of sperm out of the testicles. Vas deferens is a muscular tube about 45 cm long and 2.5 mm in diameter. From the tail of the epididymis, it passes upward within the spermatic cord and inguinal canal and enters the pelvic cavity. There, it turns medially and approaches the urinary bladder. After passing between the bladder and ureter, the duct turns downward behind the bladder and widens into a terminal ampulla.

The vas deferens ends by uniting with the duct of the seminal vesicle. The duct has a very narrow lumen and a thick wall of smooth muscle well innervated by sympathetic nerve fibers.

The wall of the vas deferens consists of:

- An inner mucosa with the same pseudostratified epithelium as that of the epididymis, plus a lamina propria.

- An extremely thick muscularis. During ejaculation, the smooth muscle in the muscularis creates strong peristaltic waves that rapidly propel sperm through the ductus deferens to the urethra.

- An outer adventitia of connective tissue.

The ejaculatory duct is about 2 cm (1 in.) long and is formed by the union of the duct from the seminal vesicle and the ampulla of the vas deferens (see Figure 2). The short ejaculatory ducts form just superior to the base (superior portion) of the prostate and pass inferiorly and anteriorly through the prostate. They terminate in the prostatic urethra, where they eject sperm and seminal vesicle secretions just before the release of semen from the urethra to the exterior.

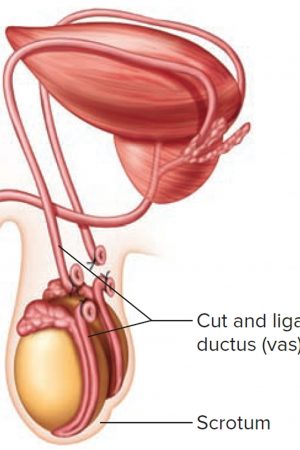

Figure 1. Vas deferens location

Figure 2. Vas deferens

What is the function of the vas deferens

The ductus deferens or vas deferens, stores and transports sperm during ejaculation from the epididymis to the urethra. During ejaculation, vas deferens coordinated muscular contractions propel the spermatozoa toward the urethra. However, the vas deferens does not serve only as a conduit, but also contributes to secretion of fluid for sperm transport and possibly to resorption of spermatozoan remnants from the duct lumen 1.

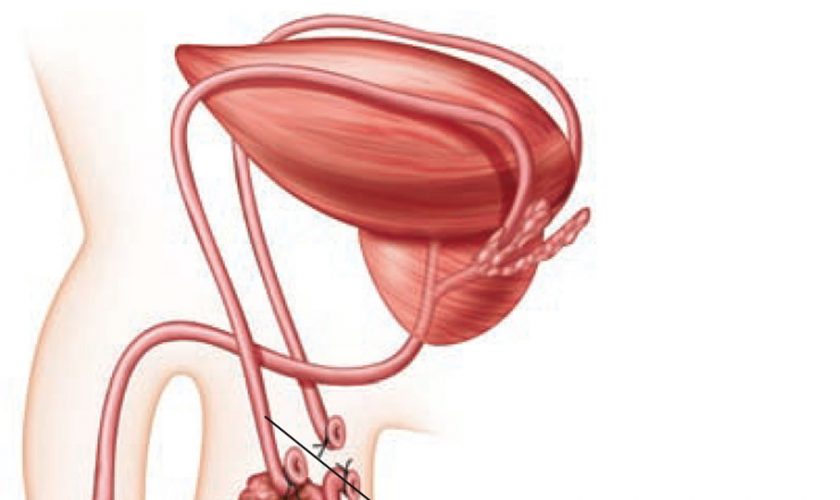

Vasectomy or ‘male sterilization’ : In this minor surgery, the physician makes a small incision into both sides of the scrotum, transects both vas deferens, and then closes the cut ends, either by tying them off or by fusing them shut by cauterization. Although sperm continue to be produced, they can no longer exit the body and are phagocytized in the epididymis.

Figure 3. Vasectomy

Vas deferens pain

The cause of the post-vasectomy pain syndrome is unclear 2. Some postulated etiologies include epididymal congestion, tender sperm granuloma and/or nerve entrapment at the vasectomy site. Vasectomy reversal is reportedly successful for relieving pain in some patients 2.

Chronic scrotal pain

Chronic scrotal pain is defined as pain in the scrotum of more than 3-month duration, appears to be a very common condition and well recognized symptom of young males 3, 4. Chronic scrotal pain is historically defined as an intermittent or constant testicular pain, unilateral or bilateral, lasting for over 3 months that interferes significantly with the patients daily activities 5.

The probable causes of chronic scrotal pain in young men are:

- Varicocele 54.1%

- Idiopathic (unknown) scrotal pain 34.4%

- Inguinal hernia 4.5%

- Genital infections 4.3%

- Hydrocele 4.2%

- Referred pain 3.3%

- Skin lesion 1.1%

- Torsion–detorsion 0.5%

- Trauma 0.2%

- Kidney stone 0.1%

Varicocele was found in 54.6% of the patients and was more common among patients with longer duration of symptoms (up to 60.6%). The prevalence of varicocele in normal young men estimated at 15–20% 6 and the prevalence of pain in individuals with varicocele is estimated between approximately 2 and 10% 7, which mean estimated prevalence of painful varicocele of 0.3–2% in normal young men population.

According to Granitsiotis et al. nearly 25% of patients with chronic scrotal pain have no obvious cause for the pain 8. In another study, no specific cause could be established in 1062 patients (34.4%) 9. The percentage of patients with idiopathic scrotal pain dropped with longer symptom duration. This may suggests that in patients with idiopathic scrotal pain who complain for longer periods of time, further evaluations were done and in most cases, varicocele was found and diagnosed as the presumed cause of the symptoms.

What is varicocele ?

A varicocele is an enlargement of the veins within the loose bag of skin that holds your testicles (scrotum) 10. A varicocele is similar to a varicose vein that can occur in your leg.

Varicoceles are a common cause of low sperm production and decreased sperm quality, which can cause infertility. However, not all varicoceles affect sperm production. Varicoceles can also cause testicles to fail to develop normally or shrink.

Most varicoceles develop over time. Fortunately, most varicoceles are easy to diagnose and many don’t need treatment. If a varicocele causes symptoms, it often can be repaired surgically.

Causes of varicocele

A varicocele forms when valves inside the veins that run along the spermatic cord prevent blood from flowing properly. Blood backs up, leading to swelling and widening of the veins. (This is similar to varicose veins in the legs).

Most of the time, varicoceles develop slowly. They are more common in men ages 15 to 25 and are most often seen on the left side of the scrotum.

A varicocele in an older man that appears suddenly may be caused by a kidney tumor, which can block blood flow to a vein. The problem is more common on the left side than the right.

Symptoms of varicocele

Symptoms include:

- Enlarged, twisted veins in the scrotum

- Painless testicle lump, scrotal swelling, or bulge in the scrotum

- Possible problems with fertility or decreased sperm count

Some men do not have symptoms.

How is varicocele diagnosed ?

You will have an exam of your groin area, including the scrotum and testicles. The health care provider may feel a twisted growth along the spermatic cord.

Sometimes the growth may not be able to be seen or felt, especially when you are lying down.

The testicle on the side of the varicocele may be smaller than the one on the other side.

Treatment of varicocele

A jock strap or snug underwear may help ease discomfort. You may need other treatment if the pain does not go away or you develop other symptoms.

Surgery to correct a varicocele is called varicocelectomy. For this procedure:

- You will receive some type of numbing medicine (anesthesia).

- The urologist will make a cut, most often in the lower abdomen, and tie off the abnormal veins. This directs blood flow in the area to the normal veins. The operation may also be done as a laparoscopic procedure (through small incisions with a camera).

- You will be able to leave the hospital on the same day as your surgery.

- You will need to keep an ice pack on the area for the first 24 hours after surgery to reduce swelling.

An alternative to surgery is varicocele embolization. For this procedure:

- A small hollow tube called a catheter (tube) is placed into a vein in your groin or neck area.

- The provider moves the tube into the varicocele using x-rays as a guide.

- A tiny coil passes through the tube into the varicocele. The coil blocks blood flow to the bad vein and sends it to normal veins.

- You will need to keep an ice pack on the area to reduce swelling and wear a scrotal support for a little while.

This method is also done without an overnight hospital stay. It uses a much smaller cut than surgery, so you will heal faster.

Outlook (Prognosis) for varicocele

A varicocele is often harmless and often does not need to be treated.

If you have surgery, your sperm count will likely increase. However, it will not improve your fertility. In most cases, testicular wasting (atrophy) does not improve unless surgery is done early in adolescence.

Possible Complications of varicocele

Infertility is a complication of varicocele.

Complications from treatment may include:

- Atrophic testis

- Blood clot formation

- Infection

- Injury to the scrotum or nearby blood vessel

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your provider if you discover a testicle lump or need to treat a diagnosed varicocele.

What is hydrocele ?

A hydrocele is a fluid-filled sac in the scrotum 11.

Causes of hydrocele

Hydroceles are common in newborn infants.

During a baby’s development in the womb, the testicles descend from the abdomen through tube into the scrotum. Hydroceles occur when this tube does not close. Fluid drains from the abdomen through the open tube and gets trapped in the scrotum. This causes the scrotum to swell.

Most hydroceles go away a few months after birth. Sometimes, a hydrocele may occur with an inguinal hernia.

Hydroceles may also be caused by:

- Buildup of the normal fluid around the testicle. This may occur because the body makes too much of the fluid or it does not drain well. (This type of hydrocele is more common in older men.)

- Inflammation or injury of the testicle or epididymis

Symptoms of hydrocele

The main symptom is a painless, swollen testicle, which feels like a water balloon. A hydrocele may occur on one or both sides.

How is hydrocele diagnosed ?

You will have a physical exam. The health care provider will find that the scrotum is swollen, but not painful to the touch. Often, the testicle cannot be felt because of the fluid around it. The size of the fluid-filled sac can sometimes be increased and decreased by putting pressure on the abdomen or the scrotum.

If the size of the fluid collection changes, it is more likely to be due to an inguinal hernia.

Hydroceles can be easily seen by shining a flashlight through the swollen part of the scrotum. If the scrotum is full of clear fluid, the scrotum will light up.

You may need an ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment for hydrocele

Hydroceles are not harmful most of the time. They are treated only when they cause infection or discomfort.

Hydroceles from an inguinal hernia should be fixed with surgery as soon as possible. Hydroceles that do not go away on their own after a few months may need surgery. A surgical procedure called a hydrocelectomy (removal of sac lining) is often done to correct the problem. Needle drainage does not work well because the fluid will come back.

Outlook (Prognosis) of hydrocele

Simple hydroceles in children often go away without surgery. In adults, hydroceles usually do not go away on their own. If surgery is needed, it is an easy procedure with very good outcomes.

Possible Complications of hydrocele

Risks from hydrocele surgery may include:

- Blood clots

- Infection

- Injury to the scrotum

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your provider if you have symptoms of hydrocele. It is important to rule out other causes of a testicular lump.

Pain in the scrotum or testicles is an emergency. If you have pain and your scrotum is enlarged, seek medical help right away to prevent the loss of the testicle.

What is inguinal hernia ?

An inguinal hernia happens when contents of the abdomen—usually fat or part of the small intestine—bulge through a weak area in the lower abdominal wall. The abdomen is the area between the chest and the hips. The area of the lower abdominal wall is also called the inguinal or groin region.

Two types of inguinal hernias are:

- Indirect inguinal hernias, which are caused by a defect in the abdominal wall that is congenital, or present at birth

- Direct inguinal hernias, which usually occur only in male adults and are caused by a weakness in the muscles of the abdominal wall that develops over time

Inguinal hernias occur at the inguinal canal in the groin region.

Figure 4. Inguinal hernia

What causes inguinal hernias ?

The cause of inguinal hernias depends on the type of inguinal hernia.

Indirect inguinal hernias. A defect in the abdominal wall that is present at birth causes an indirect inguinal hernia.

During the development of the fetus in the womb, the lining of the abdominal cavity forms and extends into the inguinal canal. In males, the spermatic cord and testicles descend out from inside the abdomen and through the abdominal lining to the scrotum through the inguinal canal. Next, the abdominal lining usually closes off the entrance to the inguinal canal a few weeks before or after birth. In females, the ovaries do not descend out from inside the abdomen, and the abdominal lining usually closes a couple of months before birth 12.

Sometimes the lining of the abdomen does not close as it should, leaving an opening in the abdominal wall at the upper part of the inguinal canal. Fat or part of the small intestine may slide into the inguinal canal through this opening, causing a hernia. In females, the ovaries may also slide into the inguinal canal and cause a hernia.

Indirect hernias are the most common type of inguinal hernia 13. Indirect inguinal hernias may appear in 2 to 3 percent of male children; however, they are much less common in female children, occurring in less than 1 percent 14.

Direct inguinal hernias. Direct inguinal hernias usually occur only in male adults as aging and stress or strain weaken the abdominal muscles around the inguinal canal. Previous surgery in the lower abdomen can also weaken the abdominal muscles.

Females rarely form this type of inguinal hernia. In females, the broad ligament of the uterus acts as an additional barrier behind the muscle layer of the lower abdominal wall. The broad ligament of the uterus is a sheet of tissue that supports the uterus and other reproductive organs.

Who is more likely to develop an inguinal hernia ?

Males are much more likely to develop inguinal hernias than females. About 25 percent of males and about 2 percent of females will develop an inguinal hernia in their lifetimes.2 Some people who have an inguinal hernia on one side will have or will develop a hernia on the other side.

People of any age can develop inguinal hernias. Indirect hernias can appear before age 1 and often appear before age 30; however, they may appear later in life. Premature infants have a higher chance of developing an indirect inguinal hernia. Direct hernias, which usually only occur in male adults, are much more common in men older than age 40 because the muscles of the abdominal wall weaken with age 15.

People with a family history of inguinal hernias are more likely to develop inguinal hernias. Studies also suggest that people who smoke have an increased risk of inguinal hernias 16.

What are the signs and symptoms of an inguinal hernia ?

The first sign of an inguinal hernia is a small bulge on one or, rarely, on both sides of the groin—the area just above the groin crease between the lower abdomen and the thigh. The bulge may increase in size over time and usually disappears when lying down.

Other signs and symptoms can include:

- discomfort or pain in the groin—especially when straining, lifting, coughing, or exercising—that improves when resting

- feelings such as weakness, heaviness, burning, or aching in the groin

- a swollen or an enlarged scrotum in men or boys

Indirect and direct inguinal hernias may slide in and out of the abdomen into the inguinal canal. A health care provider can often move them back into the abdomen with gentle massage.

What are the complications of inguinal hernias ?

Inguinal hernias can cause the following complications:

- Incarceration. An incarcerated hernia happens when part of the fat or small intestine from inside the abdomen becomes stuck in the groin or scrotum and cannot go back into the abdomen. A health care provider is unable to massage the hernia back into the abdomen.

- Strangulation. When an incarcerated hernia is not treated, the blood supply to the small intestine may become obstructed, causing “strangulation” of the small intestine. This lack of blood supply is an emergency situation and can cause the section of the intestine to die.

How are inguinal hernias treated ?

Repair of an inguinal hernia via surgery is the only treatment for inguinal hernias and can prevent incarceration and strangulation. Health care providers recommend surgery for most people with inguinal hernias and especially for people with hernias that cause symptoms. Research suggests that men with hernias that cause few or no symptoms may be able to safely delay surgery until their symptoms increase.3, 6 Men who delay surgery should watch for symptoms and see a health care provider regularly. Health care providers usually recommend surgery for infants and children to prevent incarceration.1 Emergent, or immediate, surgery is necessary for incarcerated or strangulated hernias.

A general surgeon—a doctor who specializes in abdominal surgery—performs hernia surgery at a hospital or surgery center, usually on an outpatient basis. Recovery time varies depending on the size of the hernia, the technique used, and the age and health of the person.

Hernia surgery is also called herniorrhaphy. The two main types of surgery for hernias are:

- Open hernia repair. During an open hernia repair, a health care provider usually gives a patient local anesthesia in the abdomen with sedation; however, some patients may have

sedation with a spinal block, in which a health care provider injects anesthetics around the nerves in the spine, making the body numb from the waist down

general anesthesia

The surgeon makes an incision in the groin, moves the hernia back into the abdomen, and reinforces the abdominal wall with stitches. Usually the surgeon also reinforces the weak area with a synthetic mesh or “screen” to provide additional support.

- Laparoscopic hernia repair. A surgeon performs laparoscopic hernia repair with the patient under general anesthesia. The surgeon makes several small, half-inch incisions in the lower abdomen and inserts a laparoscope—a thin tube with a tiny video camera attached. The camera sends a magnified image from inside the body to a video monitor, giving the surgeon a close-up view of the hernia and surrounding tissue. While watching the monitor, the surgeon repairs the hernia using synthetic mesh or “screen.”

People who undergo laparoscopic hernia repair generally experience a shorter recovery time than those who have an open hernia repair. However, the surgeon may determine that laparoscopy is not the best option if the hernia is large or if the person has had previous pelvic surgery.

Most adults experience discomfort and require pain medication after either an open hernia repair or a laparoscopic hernia repair. Intense activity and heavy lifting are restricted for several weeks. The surgeon will discuss when a person may safely return to work. Infants and children also experience some discomfort; however, they usually resume normal activities after several days.

Surgery to repair an inguinal hernia is quite safe, and complications are uncommon. People should contact their health care provider if any of the following symptoms appear:

- redness around or drainage from the incision

- fever

- bleeding from the incision

- pain that is not relieved by medication or pain that suddenly worsens

Possible long-term complications include:

- long-lasting pain in the groin

- recurrence of the hernia, requiring a second surgery

- damage to nerves near the hernia

How can inguinal hernias be prevented ?

People cannot prevent the weakness in the abdominal wall that causes indirect inguinal hernias. However, people may be able to prevent direct inguinal hernias by maintaining a healthy weight and not smoking.

People can keep inguinal hernias from getting worse or keep inguinal hernias from recurring after surgery by

- avoiding heavy lifting

- using the legs, not the back, when lifting objects

- preventing constipation and straining during bowel movements

- maintaining a healthy weight

- not smoking.

- Koslov DS, Andersson K-E. Physiological and pharmacological aspects of the vas deferens—an update. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2013;4:101. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3749770/[↩]

- Vasectomy reversal for the post-vasectomy pain syndrome: a clinical and histological evaluation. J Urol. 2000 Dec;164(6):1939-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11061886[↩][↩]

- Aljumaily A, Al-Khazraji H, Gordon A, Lau S, Jarvi KA. Characteristics and Etiologies of Chronic Scrotal Pain: A Common but Poorly Understood Condition. Pain Research & Management. 2017;2017:3829168. doi:10.1155/2017/3829168. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5352901/[↩]

- Rottenstreich M, Glick Y, Gofrit ON. Chronic scrotal pain in young adults. BMC Research Notes. 2017;10:241. doi:10.1186/s13104-017-2590-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5496592/[↩]

- Analysis and management of chronic testicular pain. Davis BE, Noble MJ, Weigel JW, Foret JD, Mebust WK. J Urol. 1990 May; 143(5):936-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2329609[↩]

- Evaluation of scrotal masses. Crawford P, Crop JA. Am Fam Physician. 2014 May 1; 89(9):723-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24784335/[↩]

- Outcomes of varicocele ligation done for pain. Peterson AC, Lance RS, Ruiz HE. J Urol. 1998 May; 159(5):1565-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9554356/[↩]

- Chronic testicular pain: an overview. Granitsiotis P, Kirk D. Eur Urol. 2004 Apr; 45(4):430-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15041105/[↩]

- Rottenstreich M, Glick Y, Gofrit ON. Chronic scrotal pain in young adults. BMC Research Notes. 2017;10:241. doi:10.1186/s13104-017-2590-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5496592[↩]

- Varicocele. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001284.htm[↩]

- Hydrocele. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000518.htm[↩]

- Aiken JJ, Oldham KT. Chapter 38: Inguinal hernias. In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1362–1368.[↩]

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/189563-overview#aw2aab6b2b3[↩]

- Kelly KB, Ponsky TA. Pediatric abdominal wall defects. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2013;93(5):1255–1267.[↩]

- Quintas ML, Rodrigues CJ, Yoo JH, Rodrigues Junior AJ. Age related changes in the elastic fiber system of the interfoveolar ligament. Revista do Hospital das Clínicas. 2000;55(3):83–86.[↩]

- Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13(4):343–403.[↩]