Cloacal exstrophy

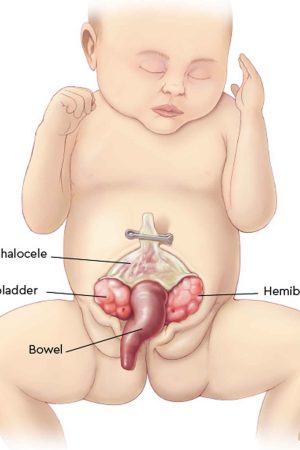

Cloacal exstrophy, also known as OEIS Syndrome, occurs when a portion of the large intestine lies outside of the body and on either side of it and connected to it are the two halves of the bladder. The intestine may be short and the anus may not open. The bony pelvis is also split open like a book. In males, the penis is usually flat and short, with the exposed inner surface of the urethra on top. The penis is sometimes split into a right and left half. In girls, the clitoris is split into a right half and left half and there may be one or two vaginal openings. Cloacal exstrophy (OEIS syndrome) is a very rare birth defect, affecting 1 in every 250,000 births. Although cloacal exstrophy is a serious condition and requires a series of operations, the long-term outcome is good for many children. Patients and families need to be counseled about the complexity of the anomaly, the need for multiple procedures, and long-term expectations for continence, sexual function, and fertility.

Cloacal exstrophy is known as OEIS Syndrome because of the four features that are typically found together 1:

- Omphalocele: Some of the abdominal organs protrude through an opening in the abdominal muscles in the area of the umbilical cord. The omphalocele may be small, with only a portion of the intestine protruding outside the abdominal cavity, or large, with many of the abdominal organs (including intestine, liver and spleen) protruding outside the abdominal cavity.

- Exstrophy of the bladder and rectum: The bladder is open and separated into two halves. The rectum and colon are similarly open and the segment of the rectum is placed between the bladder halves on the surface of the abdomen.

- Imperforate anus: The anus has not been formed or perforated and the colon connects to the bladder.

- Spinal defects: These defects may either be major or minor. Often children born with cloacal exstrophy are also born with some degree of spina bifida.

With cloacal exstrophy there are often other birth defects, like spina bifida. This occurs in up to 75 percent of cases. Kidney abnormalities and omphalocele are also common. An omphalocele is when an infant’s intestine or other abdominal organs are open to the outside the body. This is from a hole in the belly button (navel) area. The intestines are covered only by a thin layer of tissue and can be easily seen.

Cloacal exstrophy (OEIS Syndrome) is a complex anomaly that often requires several surgical procedures and requires lifelong medical follow-up care.

As soon as possible, surgical reconstruction is done. Surgery is major, and often done in parts. The schedule of surgery depends on the child’s condition and overall health. Surgery can return the bladder and bowel organs back into the body, to a healthy position. It can provide ways for bowel and urinary control, better kidney function, and improve the way the sex organs or genitals look.

Reconstruction surgery often starts within the first few days of life. It is sometimes delayed to allow the baby to grow and develop. Surgical repair is generally divided into steps and include:

- Repair of spinal abnormalities, and if needed, the repair of a large omphalocele.

- Once the child has recovered from spinal surgery, the gastrointestinal tract is treated. Many babies require a stoma because the colon is not normal, and the anus is not formed. The stoma will allow for waste to be released from the intestines to a pouch on the outside of the body.

- Closure of the exposed bladder and bowel and reconstruction of the genitals are next. This may be done in steps if the pelvic bones are widely separated. For a successful closure, a pelvic osteotomy (cutting the bones to allow the pelvis to close more easily) is critical. In some cases, the abdominal wall, the bladder and genitals (genitourinary system) and the bowel may be repaired at the same time. Bladder reconstruction often includes the use of a catheter for some time.

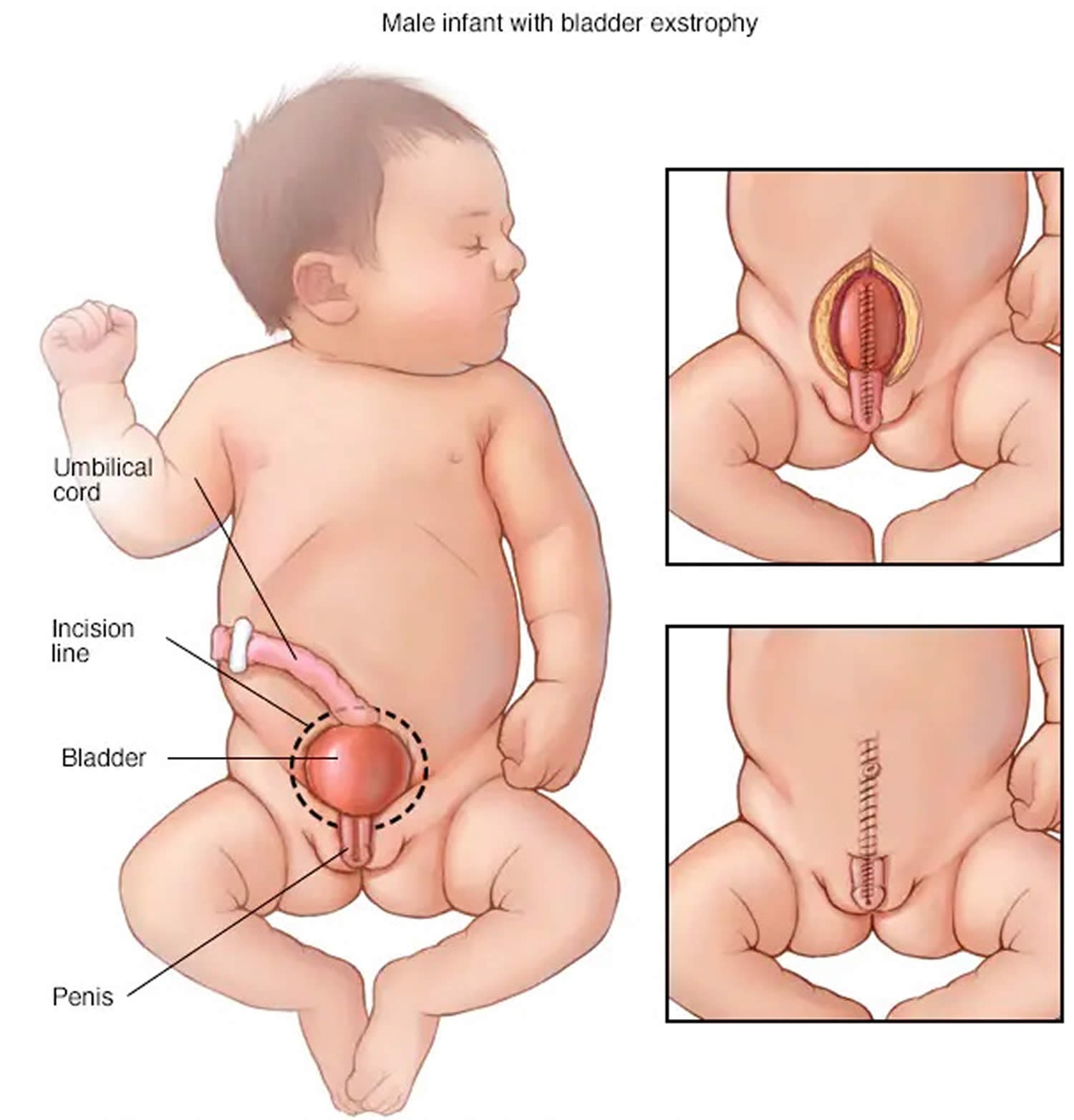

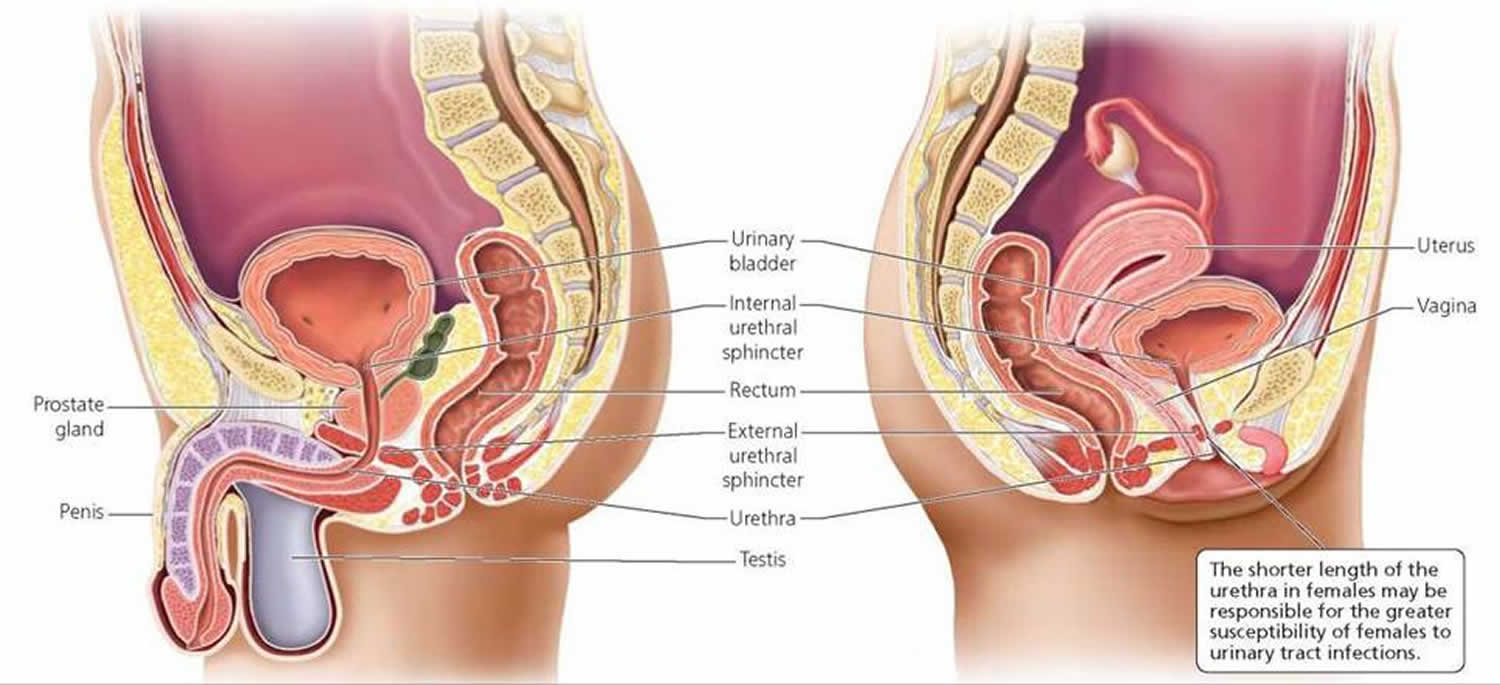

Figure 1. Cloacal exstrophy

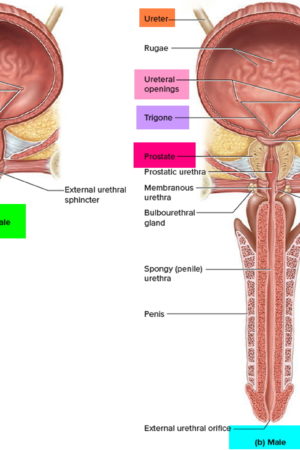

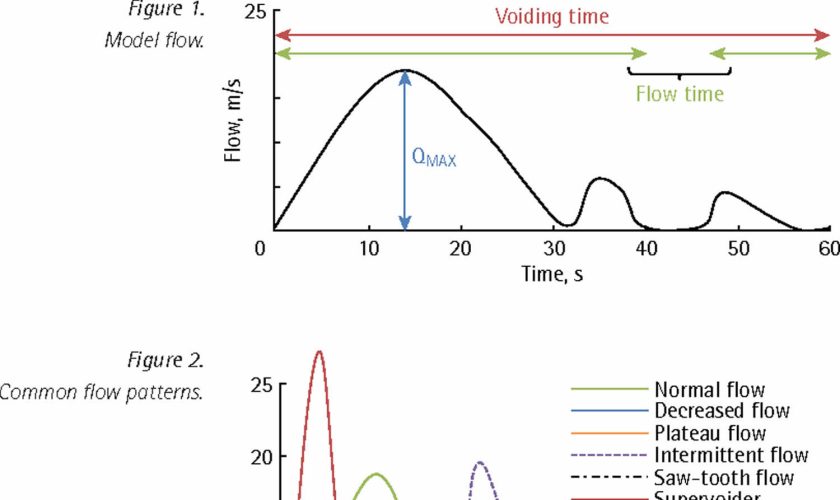

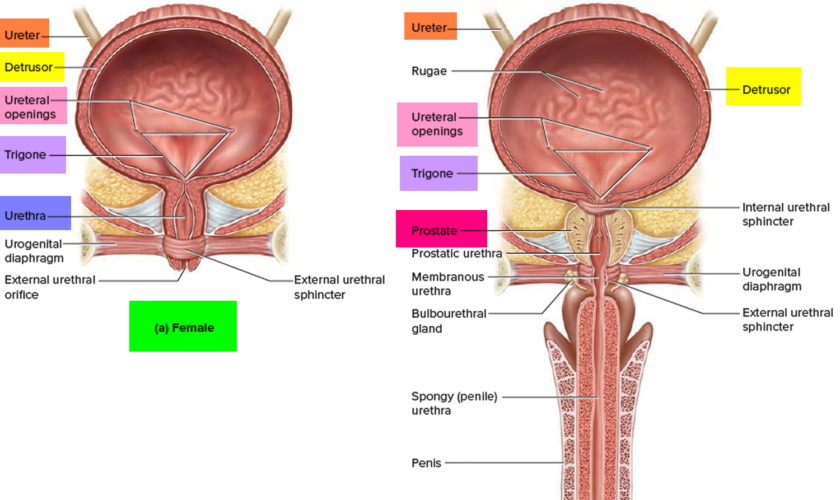

[Source 2 ]Figure 2. Cloacal exstrophy ultrasound

Footnote: Fetal ultrasound at 36 weeks’ gestation demonstrating bowel loops herniating between 2 bladder plates (“elephant trunk”).

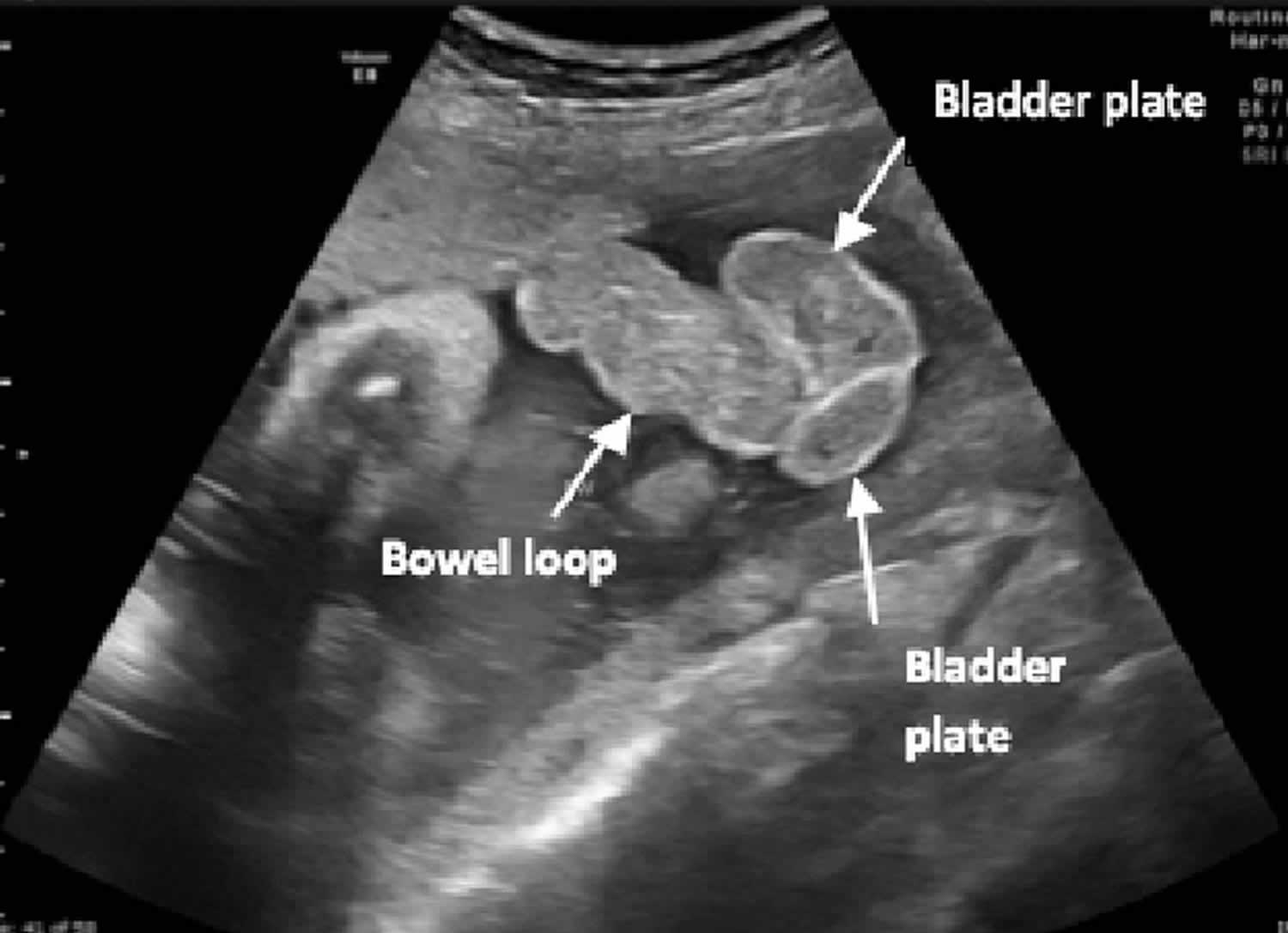

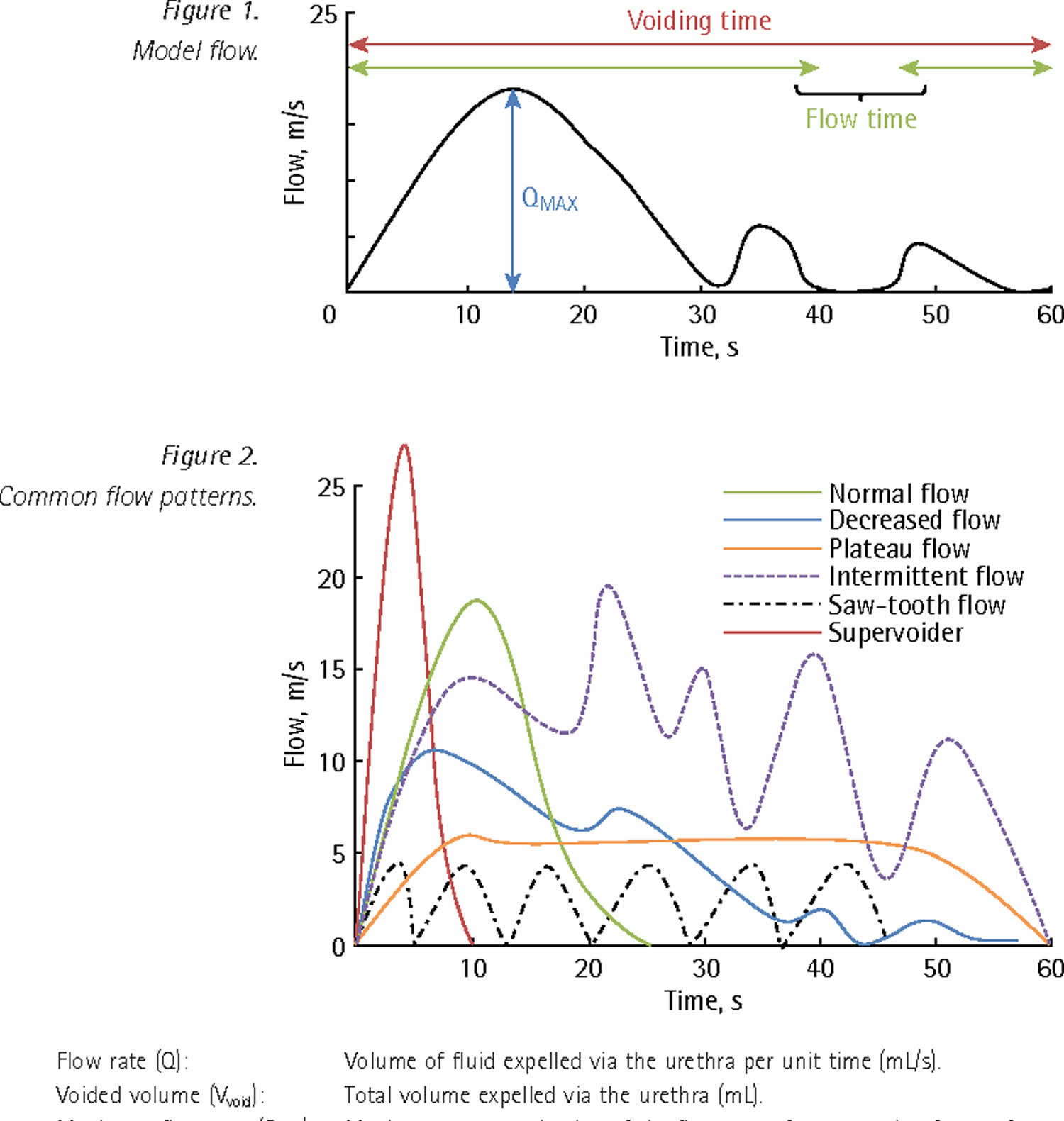

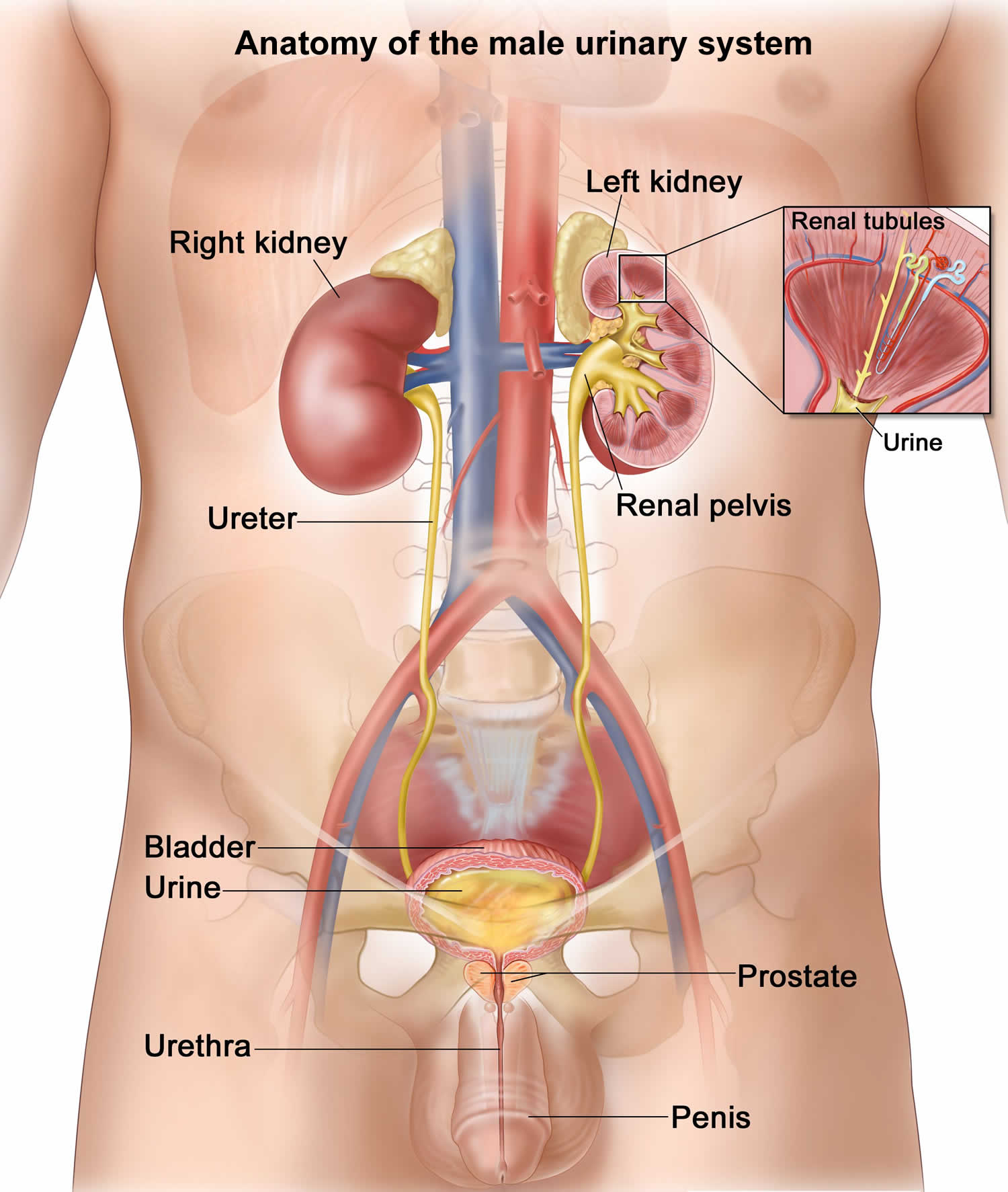

[Source 3 ]Figure 3. Cloacal bladder exstrophy female infant

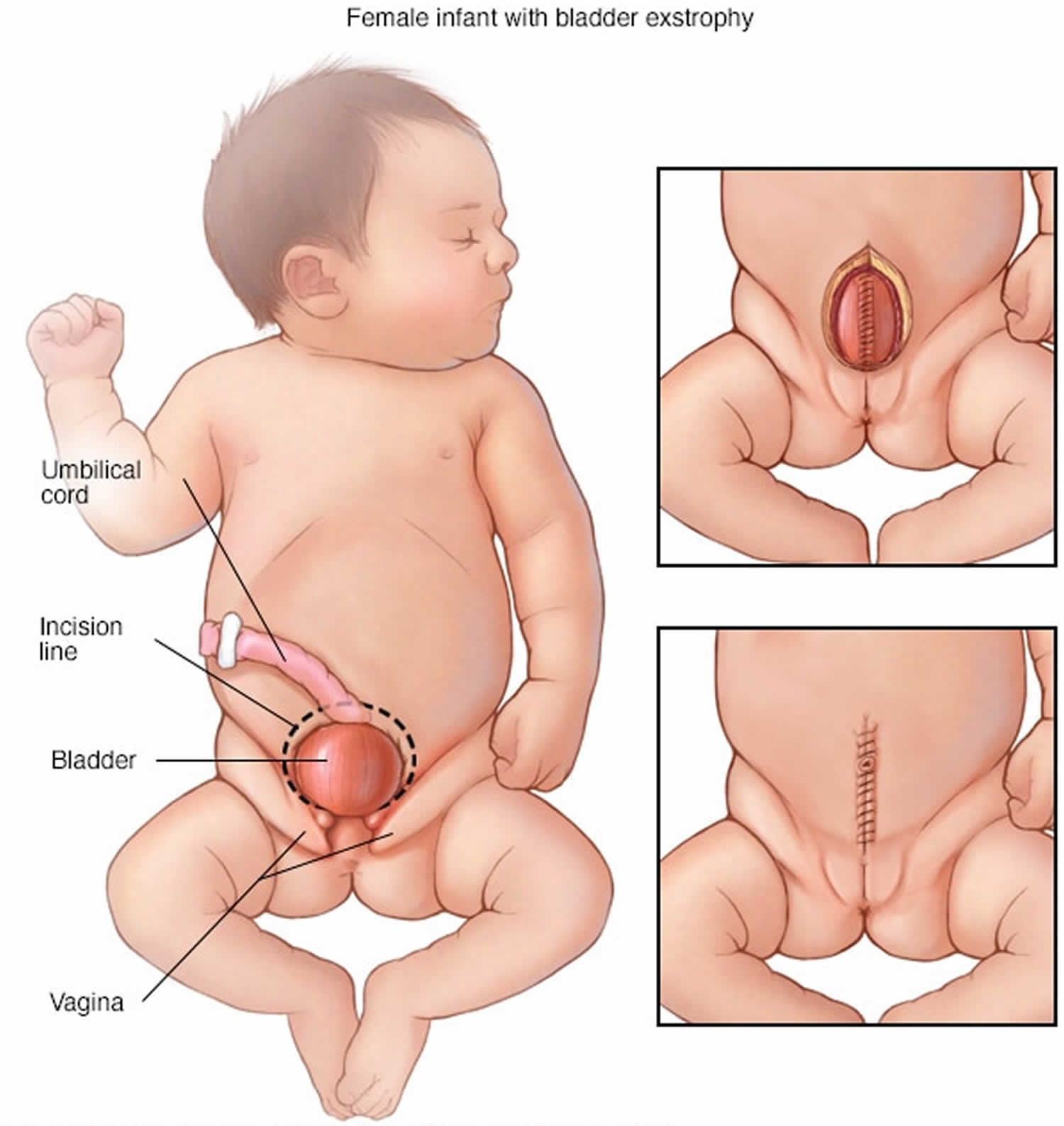

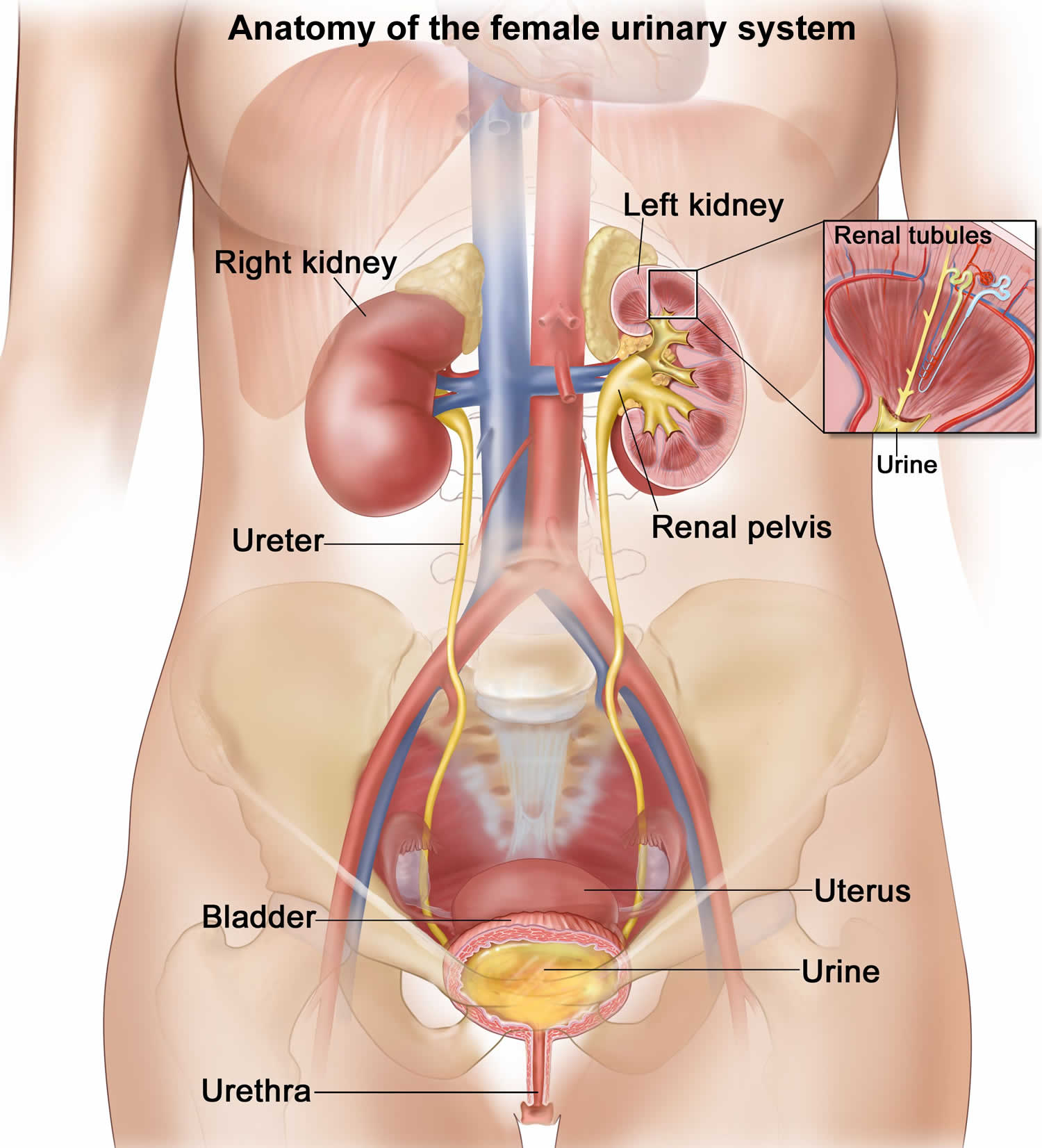

Figure 4. Cloacal bladder exstrophy male infant

Will my child be able to have children when they reach adulthood?

In many cases, the answer to this question is: yes. But almost always, assisted fertility is necessary for adults.

With regard to sexuality, males are generally potent, but some report inadequate phallus or residual curvature. Females report normal sexual function 4.

With respect to fertility and childbearing, retrograde ejaculation or iatrogenic obstruction of the ejaculatory ducts or vas deferens after surgical reconstruction may result in abnormal semen analysis. Antegrade ejaculation is preserved after single-stage repair, but abnormal semen parameters are common. However, fertilization, with viable pregnancy, has been achieved by male patients with cloacal exstrophy 5.

Females have had successful pregnancies 6. Cesarean delivery is recommended to avoid injury to continence mechanism. Postpartum uterine prolapse is common because of aggravation of preexisting abnormal pelvic support.

Cloacal exstrophy causes

The cause of cloacal exstrophy is currently unknown, so there is also no known way to prevent it. On the basis of the known embryologic principles of cloacal development, any inciting event would have to occur early in pregnancy.

There is a higher incidence of cloacal exstrophy in families in which one member is affected as compared with the general population. Offspring of patients with exstrophy-epispadias complex have a 1 in 70 risk (500 times that of the general population) of being affected. Nevertheless, familial occurrence is uncommon in large series 7. The heritability of cloacal exstrophy has not been established, because no offspring have been reported. Moreover, there’s no evidence to suggest that anything done by expectant parents leads to the condition.

At present, 22q11.2 duplication is the genetic variant most commonly associated with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex 8.

Cloacal exstrophy has been reported in twins. Concordance rates show strong evidence of genetic effects 9, but less than 100% concordance among identical twins suggests some role for environmental effect on development of exstrophy-epispadias.

A higher incidence of bladder exstrophy is observed in infants of younger mothers and in those with relatively high parity.

Maternal tobacco exposure is associated with more severe defects (cloacal vs classic exstrophy).

Growing evidence suggests an increased incidence of cloacal exstrophy and bladder exstrophy-epispadias with in-vitro fertilization (IVF) pregnancies 10.

Cloacal exstrophy symptoms

In some cases, cloacal exstrophy is detected from a routine prenatal ultrasound. In other cases, it isn’t diagnosed until birth, when physicians can clearly see the exposed organs.

Antenatal ultrasound findings suggestive of exstrophy-epispadias complex include the following:

- Repeated failure to visualize the bladder on ultrasound

- Lower-abdominal-wall mass

- Low-set umbilical cord

- Abnormal genitalia

- Increased pelvic diameter

Additional antenatal ultrasound findings suggestive of cloacal exstrophy include the following:

- Omphalocele

- Limb abnormalities

- Myelomeningocele

- Trunk sign from prolapsed intestine

Increased use of fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may further improve the accuracy of antenatal diagnosis, but this test is not necessary if suspicion is high on the basis of ultrasound findings.

Classic bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy are obvious to all in the delivery room. Variants of the exstrophy-epispadias complex exist, including skin-covered bladder exstrophy, duplicate bladders, superior vesical fistula, and epispadias with major bladder prolapse 11. Most exstrophy variants and epispadias are also identifiable at birth. Unrecognized female epispadias may present as persistent childhood incontinence. Unrecognized split-symphysis variants of exstrophy may be identified in childhood only because of persistent incontinence or a waddling gait.

Physical examination

Patients with classic bladder exstrophy or epispadias typically appear as term infants. Patients with cloacal exstrophy, however, are often preterm. They may have respiratory embarrassment requiring mechanical ventilation.

Abdominal findings

In classic cloacal bladder exstrophy (see the images above), the bladder is open on the lower abdomen, with mucosa fully exposed through a triangular fascial defect. The abdominal wall appears long because of a low-set umbilicus on the upper edge of the bladder plate. The distance between the umbilicus and anus is foreshortened. The recti diverge distally, attaching to the widely separated pubic bones. Indirect inguinal hernias are frequent (>80% of males, >10% of females) because of wide inguinal rings and the lack of an oblique inguinal canal.

Nearly all patients with cloacal exstrophy have an associated omphalocele. The bladder is open and separated into two halves, flanking the exposed interior of the cecum. Openings to the remainder of the hindgut and to one or two appendices are evident within the cecal plate. Terminal ileum may prolapse as a “trunk” of bowel onto the cecal plate.

In cloacal exstrophy variants, the pubic symphysis is widely separated, and the recti diverge distally. The umbilicus is low or elongated. A small superior bladder opening or a patch of isolated bladder mucosa may be present. The intact bladder may be externally covered by only a thin membrane. Isolated ectopic bowel segments have been reported.

Genital findings

In describing the anatomy of the penis, the terms dorsal and ventral refer to a normal phallus in the erect state. The dorsal surface is in continuity with the abdominal wall, and the ventral surface is in continuity with the scrotum.

In cloacal exstrophy, the penis is generally quite small and bifid, with a hemiglans located just caudal to each hemibladder. Infrequently, the phallus may be intact in the midline. In females, the clitoris is bifid, and two vaginas are present. The anus is absent.

In exstrophy variants, the genitalia generally are intact (see the image below), though epispadias can occur.

In classic bladder exstrophy in males, the phallus is short and broad with upward curvature (dorsal chordee). The glans lies open and flat like a spade, and the dorsal component of the foreskin is absent. The urethral plate extends the length of the phallus without a roof. The bladder plate and urethral plate are in continuity, with the verumontanum and ejaculatory ducts visible within the prostatic urethral plate. The anus is anteriorly displaced with a normal sphincter mechanism.

In classic bladder exstrophy in females, the clitoris is uniformly bifid with divergent labia superiorly. The open urethral plate is in continuity with the bladder plate. The vagina is anteriorly displaced. The anus is anteriorly displaced with a normal sphincter mechanism.

In male epispadias, the phallus is short and broad with upward curvature (dorsal chordee). The glans lies open and flat like a spade, and the dorsal component of the foreskin is absent. The urethral meatus is located on the dorsal penile shaft, anywhere between the penopubic angle and the proximal margin of the glans.

In female epispadias, the clitoris is most often bifid with divergent labia superiorly. The dorsal aspect of the urethra is open distally. The urethra and bladder neck are patulous and may allow visualization of bladder. Bladder mucosa may prolapse through the bladder neck.

Musculoskeletal findings

In classic bladder exstrophy, the pubic symphysis is widely separated. Divergent rectus muscles remain attached to the pubis. External rotation of the innominate bones results in a waddling gait in ambulatory patients but does not appear to result in orthopedic problems later in life.

In cloacal exstrophy, the examination is the same as for bladder exstrophy. As many as 65% of patients have a clubfoot or major deformity of a lower extremity. As many as 80% of patients have vertebral anomalies.

In split-symphysis variants of exstrophy, the pubic symphysis is widely separated (see the image below), and the rectus muscles are divergent.

Neurologic findings

In cloacal exstrophy, as many as 95% of patients have myelodysplasia, which may include myelomeningocele, lipomeningocele, meningocele, or other forms of occult dysraphism. These patients are at risk for neurologic deterioration, and they should be observed closely. Early neurosurgical consultation is appropriate if a radiographic abnormality of the spinal cord or canal is observed.

Cloacal exstrophy diagnosis

Cloacal exstrophy can usually be diagnosed by fetal ultrasound before an infant is born. Upon birth, a physical exam will confirm the diagnosis.

Laboratory studies

Before complex reconstruction of the urinary tract, it is important to obtain information about the patient’s baseline renal function. In patients with cloacal exstrophy, losses from the terminal ileum short-gut physiology can result in significant electrolyte abnormalities.

Imaging studies

Baseline examination of the kidneys with ultrasonography is recommended for all patients with exstrophy because increased bladder pressure after bladder closure can lead to hydronephrosis and upper urinary tract deterioration. Congenital upper urinary tract anomalies are uncommon with classic exstrophy and epispadias but are present in approximately one third of patients with cloacal exstrophy (eg, ectopic pelvic kidney, renal agenesis, or hydronephrosis).

Spinal ultrasound or radiography may be helpful. Myelodysplasia should be excluded in newborns with cloacal exstrophy. This can be accomplished by means of ultrasound early in life. In cloacal exstrophy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended to help identify occult abnormalities that may predispose to symptomatic spinal cord tethering.

Bilateral vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is present in nearly all patients with classic bladder exstrophy. Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is performed in early childhood to assess bladder capacity in preparation for reconstructive continence surgery. Evaluation of the bladder neck and proximal urethra is recommended in patients with epispadias in order to plan surgical management.

Managing pregnancy after a cloacal exstrophy diagnosis

Because cloacal exstrophy is a high-risk condition, you will need to be monitored throughout your pregnancy. In some cases, pregnancy may be complicated by polyhydramnios (excess amniotic fluid) during the third trimester, which may trigger preterm labor and delivery. Your delivery should also be planned at our state-of-the-art facility. This way, our delivery team can address any complications should they arise and the baby will have immediate access to treatment and the best surgical professionals.

Cloacal exstrophy treatment

Cloacal exstrophy is treated through surgical repair after birth, usually in stages to address each defect. This requires an in-depth treatment plan to be created for your child’s specific needs. The extent of cloacal exstrophy surgery required for your baby depends on the type and severity of his or her abnormalities.

Your child will undergo a series of surgeries over a number of years — referred to as staged reconstruction. The exact timing, nature and outcome of each cloacal exstrophy surgery will depend on your child’s particular situation. Your child’s surgeons will create a treatment plan based on the type and the extent of your child’s condition and discuss the plan with you. Usually surgery begins in the first days of life with the highest-priority procedure. Surgeons usually repair the bladder, create a colostomy (an opening in the colon with an attached “bag” that allows stool to pass) and repair the abdominal wall defect.

Babies with spinal defects usually have them repaired sometime in the first few days of life. Later surgeries include urinary and genital reconstruction, as well as an operation to create a rectum and close the colostomy opening. There are no fetal interventions (surgical procedures while inside the uterus) for cloacal exstrophy.

Treatment may include:

- Abdominal repair: Typically, soon after your child is born, the surgeons will repair the omphalocele by closing the bladder and creating a colostomy so your child can eliminate stool. With a colostomy, the large intestine is separated from the bladder halves and reclosed. The two halves of the bladder are brought together and placed into the abdomen. The end of the large intestine is brought to the surface of the skin through an opening in the abdomen. A plastic bag, called a colostomy pouch, is placed over the opening to collect the stool.

- Other surgery, such as surgery to repair the spine, may be planned around the initial stage of the abdominal repair.

After the initial surgery, your child will remain in the hospital where we will monitor the intestine as it begins to function. Our team will work with you and your family to ensure that the plan for your child is clear and that you have access to the supports you need.

- Osteotomies: Once your child has healed from his first procedure and had some time to grow, we will schedule the second stage of the repair. This primarily involves working on the bladder. The orthopedic surgeon on our team will perform osteotomies to help ensure that your child’s pelvis can best support the bladder over time. During the osteotomy the hip bones are cut and adjusted. Your child will need to be in traction or in a spica cast for several weeks following this surgery.

- Pull-through procedure: If your child was born with a significant amount of colon and is capable of forming solid stool, a surgical procedure, known as a “pull through” may eventually be performed. The purpose of this procedure is to connect the colon to the rectum.

Subsequent surgeries may also involve major urinary reconstructive surgery and further genital reconstruction. These issues will be discussed with you and your family as your child grows up.

Cloacal exstrophy repair

Reconstruction of exstrophy-epispadias complex remains one of the greatest challenges facing the pediatric urologist. Many modifications in surgical procedures have improved outcomes, but the optimal approach remains uncertain. Longitudinal prospective assessment of the two main current surgical approaches (staged procedure and total reconstruction) is critical for optimizing functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Complete primary reconstruction is now more than 20 years old; however, each approach is in a constant state of minor modification. Data on this approach continue to mature and are updated almost yearly 12. Analysis of each experience focuses on daytime continence with volitional voiding, need for further surgical procedures, and complication rates. In experienced hands, the safety and efficacy of the different approaches are comparable.

Goals of therapy include provision of urinary continence with preservation of renal function and reconstruction of functional and cosmetically acceptable genitalia. Creation of a neoumbilicus is also important to many of these patients.

Surgical techniques used in the treatment of exstrophy-epispadias complex include the following:

- Staged functional closure for classic bladder exstrophy (ie, modern staged repair of exstrophy) 13

- Complete primary repair for classic bladder exstrophy

- Urinary diversion for classic bladder exstrophy

- Closure for cloacal exstrophy

- Gender reassignment

Staged functional closure for classic bladder exstrophy

Modern staged repair of exstrophy, which represents the traditional surgical approach, comprises a series of operations. Initial bladder closure is completed within 72 hours of birth. If this is delayed, pelvic osteotomies are required to facilitate successful closure of the abdominal wall and to allow the bladder to lie within a closed and supportive pelvic ring.

Epispadias repair with urethroplasty is performed at age 12-18 months. This allows enough increase in bladder outlet resistance to improve the bladder capacity.

Bladder neck reconstruction (typically a modified Young-Dees-Leadbetter repair) is performed at age 4 years. This allows continence and correction of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Multiple modifications have been proposed. The procedure is delayed until bladder capacity is adequate; better results are reported with a capacity greater than 85 mL.

Chua et al retrospectively studied a modification of staged exstrophy repair aimed at incorporating the advantages of complete primary repair for classic bladder exstrophy by avoiding concurrent epispadias repair and adding bilateral ureteral reimplantation and bladder neck tailoring (staged repair of bladder exstrophy with bilateral ureteral reimplantation) at the initial repair 14. They found staged repair of bladder exstrophy with bilateral ureteral reimplantation to be a safe alternative for exstrophy-epispadias repair, preventing penile tissue loss and yielding long-term outcomes comparable to those of complete primary repair for classic bladder exstrophy.

The radical soft-tissue mobilization (radical soft-tissue mobilization) procedure, also referred to as the Kelly repair, has been suggested as an alternative approach to staged reconstruction of bladder exstrophy 15. Radical soft-tissue mobilization has been performed not only as the second part of a two-step strategy (after bladder closure) but also as part of a combined procedure that includes delayed bladder closure and radical soft-tissue mobilization in a single stage without pelvic osteotomy 16.

Complete primary repair for classic bladder exstrophy

Compared with modern staged repair of exstrophy, complete primary repair for classic bladder exstrophy is a newer approach to exstrophy closure. Primary bladder closure, urethroplasty, and genital reconstruction are performed in a single stage in newborns. This procedure involves complete penile disassembly in males and mobilization of the urogenital complex in females. Hypospadias is a common outcome in males and requires subsequent reconstruction.

The goal is early bladder cycling. A subset of patients have achieved continence without bladder neck reconstruction.

In a study of 34 boys treated with a modified penile disassembly technique (15 with bladder exstrophy who underwent complete primary repair for classic bladder exstrophy, 11 with penopupic epispadias after previous closure of bladder exstrophy, and eight with isolated complete epispadias), Anwar et al found the modified technique to yield excellent cosmetic results 17. Preservation of the distal urethral plate along with both hemiglans avoided shortening and prevented occurrence of hypospadias.

Urinary diversion for classic bladder exstrophy

Urinary diversion was the original surgical treatment of choice. Diversion may be performed in a patient with an extremely small bladder plate not suitable for functional closure 18. In Europe, early diversion has been widely used, with success for most exstrophy patients.

Closure for cloacal exstrophy

Treatment of myelodysplasia and gastrointestinal anomalies has priority over management of urinary and genital anomalies.

Closure can be either staged or performed in a single stage, depending on the overall condition of the child and the severity of the abdominal wall defect. If a large omphalocele is present, successful closure of the abdomen and the bladder in one stage may be difficult to accomplish.

The first stage involves separation of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary (genitourinary) tracts, closure of the colon, creation of a colostomy, and closure of the omphalocele. The bladder plates are brought together in the midline.

Because virtually all of these patients have some element of short-gut syndrome, the hindgut should be incorporated into the gastrointestinal tract to maximize absorptive surface area. Ileostomy should be avoided because of the high incidence of recurrent hospitalizations for dehydration and severe electrolyte abnormalities. The decision between rectal pull-through and permanent colostomy is based on the surgeon’s preference and the projected potential for social fecal continence 19.

Subsequent bladder closure is carried out as in surgical management of classic bladder exstrophy. The principles of complete primary repair have been applied at this point as well. Consideration may be given to continent diversion as the second stage, on the basis of poor potential for volitional voiding and continence.

Because of more severe pubic diastasis, pelvic osteotomies are required. Staged pelvic osteotomy (staged pelvic osteotomy) with gradual closure of the pelvis may be needed in severe cases 20. In a study comparing staged pelvic osteotomy before bladder closure with combined pelvic osteotomy (combined pelvic osteotomy) at the time of closure in cloacal exstrophy patients, Inouye et al found that staged pelvic osteotomy reduced preoperative diastasis more than combined pelvic osteotomy did, without appearing to incur increased rates of complication, closure failure, or incontinence 21.

Gender reassignment

Historically, all males with cloacal exstrophy underwent early gender conversion because of inadequate male genitalia. Testicular histology is normal despite frequent cryptorchidism.

Evidence suggesting that testosterone in utero has a significant impact on the developing brain has led to a change in surgical philosophy, as has anecdotal evidence suggesting that raising a 46,XY cloacal exstrophy patient as female can result in significant gender dysphoria. Cloacal exstrophy is now included as a subset of disorders of sex development 22. Multidisciplinary evaluation and both early and long-term counseling should be offered.

Intraoperative concerns

Multiple or lengthy surgical procedures with exposure to latex antigens increase the risk of latex sensitization or allergy 23. Approximately 30% of patients with bladder exstrophy have demonstrated symptoms of latex allergy, and 70% reveal sensitization (elevation of specific immunoglobulin E [IgE] antibody) to latex antigens. For practical purposes, all patients with exstrophy-epispadias complex should be considered to be latex-sensitive.

Full latex precautions are recommended in the operating room, beginning with preparation for the first operative procedure. Potential latex-containing materials in the operating room include gloves, catheters, drains, masks, anesthesia materials, bandages, and thromboembolic stockings. Polyvinyl chloride and silicone are acceptable alternatives. Latex allergy should be considered seriously in the event of intraoperative anaphylaxis. The offending agent should be removed and the surgical procedure aborted if necessary.

Treatment includes cardiopulmonary resuscitation with fluids, epinephrine, steroids, and histamine blockade. In those with a known latex allergy, premedication with steroids and histamine H1 and H2 blockers should be considered.

After cloacal exstrophy repair

The goal of surgeons and doctors is to help improve the child’s quality of life. Better tools for anesthesia and infant nutrition have helped to increase the survival rate for newborns with this condition.

Postoperatively, patients with exstrophy remain in the hospital in modified Bryant traction (legs adducted and pelvis slightly elevated) for 3 weeks after bladder closure. Alternative techniques of immobilization may be used, based on osteotomies or institutional protocol.

Bladder and kidneys are drained fully with multiple catheters during the first few weeks after closure.

Nutritional support is mandatory for patients with cloacal exstrophy. Patients with classic bladder exstrophy may also have early difficulties feeding because of the body position in traction.

It’s important to work closely with your health care team to prevent infection after surgery, and learn about long-term care. After surgery, a child born with cloacal exstrophy can usually grow to manage urine and stool in a socially acceptable way. Further operations may be needed over time to improve the child’s ability to control their bladder and bowel function. More surgery may also be needed to rebuild and/or make better the outer sex organs.

Time and patience will be important for the parents and child. Neurologic issues from spina bifida, if present, can be managed, but requires ongoing medical care.

Complications

In the treatment of complex congenital anomalies, the distinction between technical complications and problems inherent to the anomaly is not always obvious.

Failure of closure may occur. If the bladder plate is adequate, reclosure with pelvic osteotomies is recommended. In this instance, bladder closure and epispadias repair are performed in one stage. Urinary diversion is the alternative therapy.

A vesicocutaneous fistula or urethrocutaneous fistula may form after primary closure or urethral reconstruction. If spontaneous closure does not occur, surgical repair is required.

Loss of the hemiglans or corporal body has been reported as a result of complete primary repair 24.

Minor orthopedic complications may occur after osteotomy or immobilization.

Upper urinary tract deterioration is a potential complication. Causes include excessive outlet resistance and high pressure in a small-capacity reservoir and persistent VUR.

Abnormal bladder function may result in poor emptying. Clinical problems related to poor emptying include recurrent febrile infections, epididymitis, bladder stones, acute urinary retention, and rupture of the native bladder.

Bladder prolapse is a potential complication. Posterior bladder wall may prolapse through the patulous bladder neck after primary closure (see the image below). Recurrent prolapse, congestion, ischemia of bladder mucosa, or failure of ureteral drainage warrants early surgical correction.

Malignancy is a rare late complication of bladder exstrophy and is more common in untreated patients whose bladders are left exstrophic for many years. Adenocarcinoma is the most common of these malignancies, from the precursor cystitis glandularis, which is caused by chronic irritation and inflammation of exposed mucosa of the exstrophic bladder. Squamous cell carcinoma and rhabdomyosarcoma have also been reported.

Adenocarcinoma may develop adjacent to the ureterointestinal anastomosis in patients with urinary diversions that mix the urinary and fecal streams. This malignancy was reported in more than 10% of patients in one series 25. Patients younger than 25 years with ureterosigmoidostomy have a 7000-fold greater risk of adenocarcinoma of the colon than the general population (mean latency, 10 years).

Complications of short-gut syndrome are as follows:

- Paucity of hindgut and, in many cases, limited small intestine can result in electrolyte abnormalities in patients with cloacal exstrophy

- Dehydration is particularly a concern during an acute GI illness with diarrhea

- Nutritional supplementation may be required

Cloacal exstrophy prognosis

Surgical techniques to treat cloacal exstrophy have improved dramatically in recent years, which means 90% to 100% of babies survive after surgery. Their quality of life and degree of need for ongoing care vary from case to case.

Mortality with classic bladder exstrophy or epispadias is rare. Historically, cloacal exstrophy was associated with significant mortality. Reconstruction was not attempted until the 1970s. Advances in the care of critically ill neonates and recognition of the importance of early parenteral nutritional support have allowed successful reconstruction and survival of children with cloacal exstrophy.

Survival rates after surgical treatment are excellent. With respect to bladder function or continence, reports vary according to the type of reconstruction performed 26. Objective and subjective evidence indicates that many exstrophic bladders do not function normally after reconstruction and may deteriorate over time.

Continence rates of 75-90% have been reported after staged reconstruction in classic exstrophy, but more than one continence procedure may be required (eg, bladder neck reconstruction, bladder augmentation, bladder neck sling, or artificial urinary sphincter). Many of these patients require clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) through the urethra or a continent stoma because they are unable to void spontaneously to completion. Less encouraging results also are reported.

Continence results after staged reconstruction are poor (< 25%) in cloacal exstrophy because of abnormal bladder innervation in many patients. Experience with rectal reservoirs (ureterosigmoidostomy and variants) for exstrophy continence demonstrates rates higher than 95%, but they present long-term malignancy risks 27. Continent reconstruction with intestinal bladder augmentation and clean intermittent catheterization has a success rate greater than 90%.

With regard to psychosocial concerns, education, employment, and social relationships generally are not affected substantially in adults with a history of bladder exstrophy and epispadias 28. Age-appropriate adaptive behaviors may be delayed in children with chronic medical conditions 29. One study revealed below-average daily living skills and socialization but above-average self-esteem. Children may need support in disclosing their condition to new peers.

Multiple anomalies associated with cloacal exstrophy can have a significant impact on daily life. Patients are affected by permanent colostomy, the need for clean intermittent catheterization, and impaired ambulation.

Diet

Some young patients with cloacal exstrophy are seriously affected by short-gut syndrome and may depend on long-term supplemental parenteral nutrition for growth and development.

- Exstrophy and Epispadias. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1014971-overview[↩]

- Bladder Exstrophy. https://www.auanet.org/education/auauniversity/education-products-and-resources/pathology-for-urologists/urinary-bladder/histoanatomic-abnormalities/malformations/bladder-exstrophy[↩]

- Clements MB, Chalmers DJ, Meyers ML, Vemulakonda VM. Prenatal diagnosis of cloacal exstrophy: a case report and review of the literature. Urology. 2014;83(5):1162-1164. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2013.10.050[↩]

- Bujons A, Lopategui DM, Rodríguez N, Centeno C, Caffaratti J, Villavicencio H. Quality of life in female patients with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: Long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Urol. 2016 Aug. 12 (4):210.e1-6.[↩]

- Stein R, Hohenfellner K, Fisch M, Stöckle M, Beetz R, Hohenfellner R. Social integration, sexual behavior and fertility in patients with bladder exstrophy–a long-term follow up. Eur J Pediatr. 1996 Aug. 155 (8):678-83.[↩]

- Dy GW, Willihnganz-Lawson KH, Shnorhavorian M, Delaney SS, Amies Oelschlager AM, Merguerian PA, et al. Successful pregnancy in patients with exstrophy-epispadias complex: A University of Washington experience. J Pediatr Urol. 2015 Aug. 11 (4):213.e1-6.[↩]

- Gambhir L, Höller T, Müller M, Schott G, Vogt H, Detlefsen B, et al. Epidemiological survey of 214 families with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 2008 Apr. 179 (4):1539-43.[↩]

- Beaman GM, Woolf AS, Cervellione RM, Keene D, Mushtaq I, Urquhart JE, et al. 22q11.2 duplications in a UK cohort with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. Am J Med Genet A. 2019 Jan 9.[↩]

- Reutter H, Qi L, Gearhart JP, Boemers T, Ebert AK, Rösch W, et al. Concordance analyses of twins with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex suggest genetic etiology. Am J Med Genet A. 2007 Nov 15. 143A (22):2751-6.[↩]

- Wood HM, Babineau D, Gearhart JP. In vitro fertilization and the cloacal/bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: a continuing association. J Pediatr Urol. 2007 Aug. 3 (4):305-10.[↩]

- Maruf M, Benz K, Jayman J, Kasprenski M, Michaud J, Di Carlo HN, et al. Variant Presentations of the Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex: A 40-Year Experience. Urology. 2018 Dec 18.[↩]

- Bhatnagar V. Bladder exstrophy: An overview of the surgical management. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2011 Jul. 16 (3):81-7.[↩]

- Baird AD, Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Modern staged repair of bladder exstrophy: a contemporary series. J Pediatr Urol. 2007 Aug. 3 (4):311-5.[↩]

- Chua ME, Ming JM, Fernandez N, Varghese A, Farhat WA, Bagli DJ, et al. Modified staged repair of bladder exstrophy: a strategy to prevent penile ischemia while maintaining advantage of the complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol. 2018 Sep 25.[↩]

- Ben-Chaim J, Hidas G, Wikenheiser J, Landau EH, Wehbi E, Kelly MS, et al. Kelly procedure for exstrophy or epispadias patients: Anatomical description of the pudendal neurovasculature. J Pediatr Urol. 2016 Jun. 12 (3):173.e1-6.[↩]

- Leclair MD, Faraj S, Sultan S, Audry G, Héloury Y, Kelly JH, et al. One-stage combined delayed bladder closure with Kelly radical soft-tissue mobilization in bladder exstrophy: preliminary results. J Pediatr Urol. 2018 Dec. 14 (6):558-564.[↩]

- Anwar AZ, Mohamed MA, Hussein A, Shaaban AM. Modified penile disassembly technique for boys with epispadias and those undergoing complete primary repair of exstrophy: long-term outcomes. Int J Urol. 2014 Sep. 21 (9):936-40.[↩]

- Ko JS, Lue K, Friedlander D, Baumgartner T, Stuhldreher P, DiCarlo HN, et al. Cystectomy in the Pediatric Exstrophy Population: Indications and Outcomes. Urology. 2018 Jun. 116:168-171.[↩]

- Levitt MA, Mak GZ, Falcone RA Jr, Peña A. Cloacal exstrophy–pull-through or permanent stoma? A review of 53 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2008 Jan. 43 (1):164-8; discussion 168-70.[↩]

- Mathews R, Gearhart JP, Bhatnagar R, Sponseller P. Staged pelvic closure of extreme pubic diastasis in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 2006 Nov. 176 (5):2196-8.[↩]

- Inouye BM, Tourchi A, Di Carlo HN, Young EE, Mhlanga J, Ko JS, et al. Safety and efficacy of staged pelvic osteotomies in the modern treatment of cloacal exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol. 2014 Dec. 10 (6):1244-8.[↩]

- Houk CP, Lee PA. Consensus statement on terminology and management: disorders of sex development. Sex Dev. 2008. 2 (4-5):172-80.[↩]

- Shnorhavorian M, Grady RW, Andersen A, Joyner BD, Mitchell ME. Long-term followup of complete primary repair of exstrophy: the Seattle experience. J Urol. 2008 Oct. 180 (4 Suppl):1615-9; discussion 1619-20.[↩]

- Schaeffer AJ, Purves JT, King JA, Sponseller PD, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Complications of primary closure of classic bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2008 Oct. 180 (4 Suppl):1671-4; discussion 1674.[↩]

- Krishnamsetty RM, Rao MK, Hines CR, Saikaly EP, Corpus RP, DeBandi HO. Adenocarcinoma in exstrophy and defunctional ureterosigmoidostomy. J Ky Med Assoc. 1988 Aug. 86 (8):409-14.[↩]

- Kibar Y, Roth C, Frimberger D, Kropp BP. Long-term results of penile disassembly technique for correction of epispadias. Urology. 2009 Mar. 73 (3):510-4.[↩]

- Husmann DA, Rathbun SR. Long-term follow up of enteric bladder augmentations: the risk for malignancy. J Pediatr Urol. 2008 Oct. 4 (5):381-5; discussion 386.[↩]

- Mukherjee B, McCauley E, Hanford RB, Aalsma M, Anderson AM. Psychopathology, psychosocial, gender and cognitive outcomes in patients with cloacal exstrophy. J Urol. 2007 Aug. 178 (2):630-5; discussion 634-5.[↩]

- Ebert A, Scheuering S, Schott G, Roesch WH. Psychosocial and psychosexual development in childhood and adolescence within the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 2005 Sep. 174 (3):1094-8.[↩]