Curling ulcer

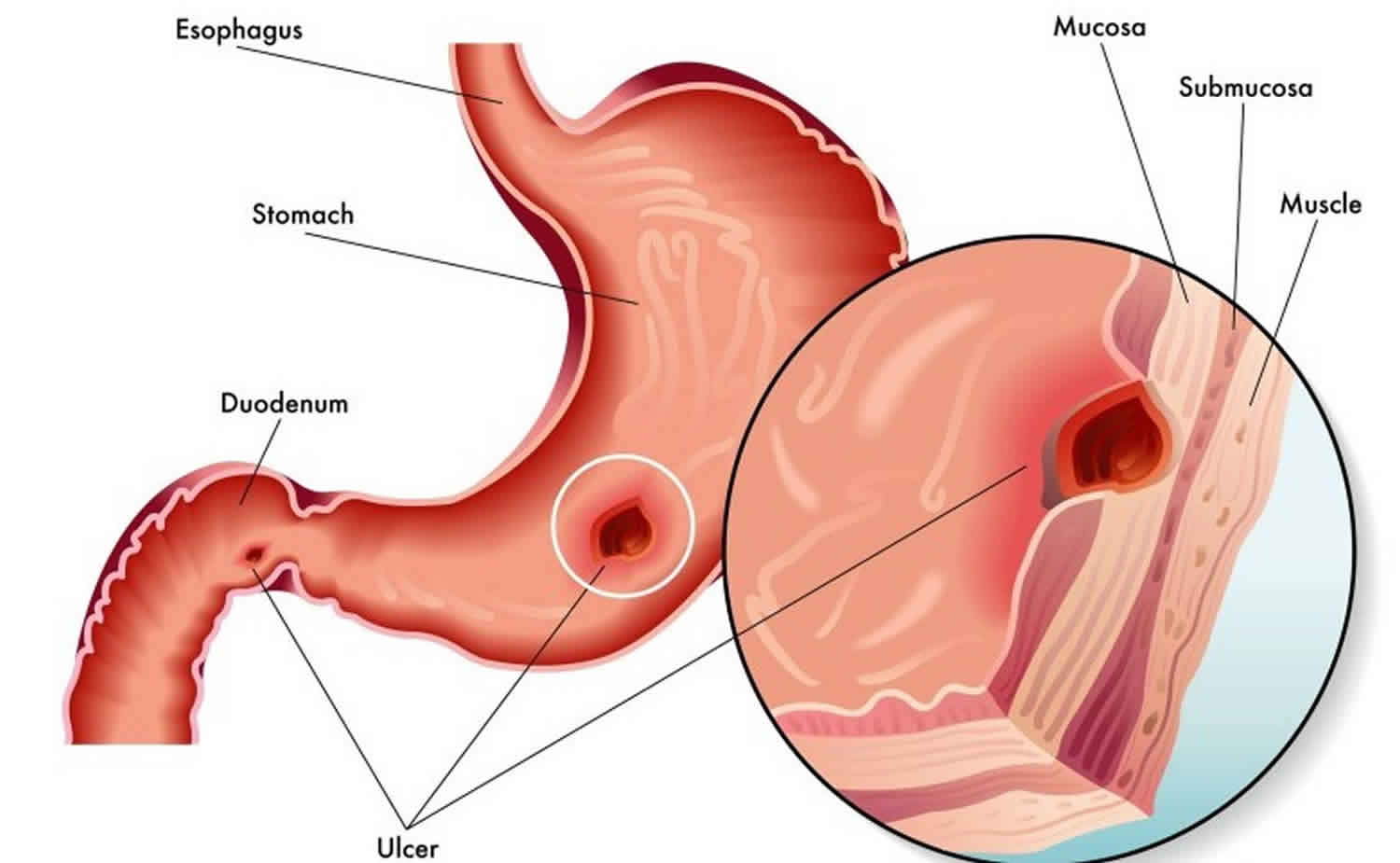

Curling ulcer is stress-induced gastritis or gastropathy secondary to systemic burns 1. Cushing ulcer is stress-induced gastritis or gastropathy in patients with acute traumatic brain injury.

Stress-induced gastritis also referred to as stress-related erosive syndrome, stress ulcer syndrome, and stress-related mucosal disease can cause mucosal erosions and superficial hemorrhages in patients who are critically ill or in those who are under extreme physiologic stress, resulting in minimal-to-severe gastrointestinal blood loss and leading to blood transfusion if not addressed in time 2.

The gastric body and fundus are common locations for stress ulcerations but can also be seen in antrum and duodenum 3.

The incidence of stress ulcer is not well known but is thought to almost always occur in severe acute illness. The most common presentation of stress ulceration is in the form of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and gastrointestinal bleed secondary to stress ulcerations may range from 1.5% to 15% depending on whether or not patients received stress ulcer prophylaxis. The incidence of stress ulceration and its complications are known to be declining with the advent of active prophylaxis methods for the prevention of stress-related gastritis. Patients with gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to stress ulceration have increased morbidity and mortality compared to those who do not have gastrointestinal bleed. Hence stress ulcer prophylaxis has been the center of many randomized clinical trials. Very rarely (less than 1% of the times), stress ulcers can cause perforation and perforation related complications 3.

Curling ulcer causes

Prolonged mechanical ventilation and coagulopathy increase the predisposition to stress gastritis. The major risk factors for the development of stress ulcerations include:

- Mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours

- Abnormal coagulation profile such as platelet count less than 50,000, INR greater than 1.5 and PTT greater than 2 times the control value

- Sepsis or septic shock

- Hypotension

- Use of vasopressors

- Use of high dose systemic corticosteroids (more than 250 mg or the equivalent of hydrocortisone per day)

- Hepatic failure

- Renal failure

- Multiorgan failure

- Burns of more than 30% of body surface area

- Head trauma

- Acute traumatic brain injury or central nervous system injury with raised intracranial pressure

- Lack of sanitation during intensive care unit (ICU) stay

- History of gastrointestinal bleeds within a year 4

Stress ulceration results from damage to the mucosal barrier secondary to systemic stress resulting in multiple superficial erosions of the gastric mucosa. The possible pathological changes leading to ulceration can be an impaired mucosal barrier where the mucosal glycoprotein is denuded by increased concentrations of refluxed bile salts or uremic toxins due to a critical illness. Increased secretion of gastric acid in response to higher secretion of gastrin hormone in patients is also thought to be responsible for stress ulceration. However, this is more commonly seen in patients with acute neurological trauma than other stress-related diseases. Helicobacter pylori infection has also been associated with stress ulcers though the evidence is limited. There could be a subgroup of critical care patients who may present with overt gastrointestinal bleeding without stress ulceration or stress-related mucosal damage, such as a patient with variceal bleeds, vascular anomalies, or diverticulosis. Hence these gastrointestinal bleeds may not respond adequately to stress ulcer prophylaxis or antireflux therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or antihistaminic 5.

Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) who receive positive pressure ventilation (PPV) for more than 3 days are especially susceptible to mucosal damage due to splanchnic hypo-perfusion, which is more pronounced at positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) levels of 15-20 cm of H2O 6.

Curling ulcer prevention

The goal of management for stress-induced gastritis is prevention or prophylaxis 7, which has been shown to reduce the incidence by 50% when treatment is started at admission. Monitor the pH of the gastric contents. The target pH value should be greater than 4.0. Anything less should prompt the clinician to double the dose of the agent used to reduce gastric acid levels if the patient was previously on prophylaxis.

Sucralfate is the primary agent for prophylaxis of stress gastritis. It has long been used as a means of decreasing the incidence of gastritis. This drug is readily available, easy to administer, and inexpensive. Sucralfate (complex salt of sucrose aluminum hydroxide and sulfate) has a positive charge and binds to the negative charge of the ulcer base to form a gel, which acts to effectively plug the ulcer base and to prevent worsening of the gastritis. For patients on mechanical ventilation, this action has been shown to decrease the risk of nosocomial pneumonias by aspiration.

Histamine 2 (H2) receptor blockers (eg, ranitidine, famotidine) have also been used for prophylaxis. Their action selectively blocks H2 receptors on the parietal cells, thereby reducing the production of hydrogen ions. The H2 blockers are readily affordable and can be administered intravenously. For active hemorrhage, a continuous infusion of H2 blockers over a 24-hour period can be used because this delivers a constant concentration to the gastric mucosa, thus promoting healing. The major adverse effect of this class of drugs is the risk of nosocomial pneumonia, which is thought to result from the suppression of gastric acid and which leads to colonization by secondary organisms and subsequent aspiration pneumonia.

Although the role of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in prophylaxis has not been fully evaluated, these agents have been recommended as first-line agents for prophylaxis 7. However, PPIs are prodrugs and usually require an acidic medium to be activated. Hence, in the fasting stressed patient, or in a subset of critical care patients who present with overt gastrointestinal bleeding but without stress ulceration or stress-related mucosal disease (eg, variceal bleeds, vascular anomalies, diverticulosis), this may not be the case. PPIs block the final common pathway of acid secretion by blocking the H-K-ATPase enzyme. In addition, there appears to be a higher risk (38.6%) of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection when PPIs are used for prophylaxis and treatment of stress ulcers than when H2 blockers are used 8.

PPIs are available in various forms (eg, tablets, microspheres, liquid [IV]). In patients who are critically ill and intubated for nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding, the administration of microspheres or intravenous preparations can be useful if the patients are thought to be bleeding from stress gastritis, especially if they have not responded to any of the previously discussed measures.

Small studies have shown the efficacy of PPIs in mechanically ventilated patients to reduce stress gastritis and have also found them to be safe and cost effective. In a comparison of PPIs and placebo, the superiority of PPIs over placebo was demonstrated in cases of bleeding peptic ulcer. PPIs were also shown to be more effective for rebleed prophylaxis versus H2 blockers.

In a review of studies from a MEDLINE search through August 2015, Barletta and colleagues 9 found that PPIs appear to be the dominant drug class used worldwide. However, when the researchers evaluated only trials that were at low risk for bias, the evidence failed to clearly support lower bleeding rates with proton pump inhibitors over histamine 2 receptor antagonists.

In a search of the Cochrane library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, ACPJC, clinical trials registries, and conference proceedings through November 2015, Alshamsi et al 10 reviewed randomized controlled trials of PPIs versus H2-receptor antagonists (H2 blockers) for stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill adults. They found that in 19 trials enrolling 2117 patients, PPIs were more effective than H2 blockers in reducing the risk of clinically important gastrointestinal (gastrointestinal) bleeding and overt gastrointestinal bleeding, without significantly increasing the risk of pneumonia or mortality.

In a more recent meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis that included 34 randomized controlled trials comprising 3220 critically ill adults who received PPIs or H2 blockers versus placebo, control, no therapy, or enteral nutrition, the strategy of stress ulcer prophylaxis was associated with significant reductions in bleeding but did not affect mortality 11.

In a retrospective study (2008-2013) of data from 200 patients at risk for stress gastropathy due to mechanical ventilation in a surgical trauma intensive care unit (ICU) at a single center, investigators noted that the incidence of clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding was low (0.50%) and that of stress gastropathy was rare in this population 12. Moreover, pharmacologic stress gastropathy prophylaxis provided no benefit once at-risk surgical and trauma patients tolerated enteral nutrition, potentially secondary to sufficient gut blood flow rending the stress gastropathy prophylaxis unnecessary 12.

A prospective observational study (2010-2015) of 40 ICU patients 13 regarding the effects of 1484 time-dependent doses of epinephrine (average dose per day at time t) on the occurrence of stress ulcer-related clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding found that an increase in the average daily epinephrine dose raised the time to occurrence of stress ulcer in these critically ill patients, as did enteral feeding. However, renal replacement therapy increased the occurrence of stress ulcers.

Curling’s ulcer signs and symptoms

Stress-induced gastritis has a variable clinical presentation, but the following clues should raise the level of clinical suspicion for Curling’s ulcer:

- Coffee ground vomitus

- Melena

- Hematemesis (in extreme cases)

- Orthostasis (unusual)

The most common mode of presentation of stress ulcers is the onset of acute upper gastrointestinal bleed like hematemesis or melena in a patient with acute critical illness 7. The patient may or may not have hemodynamic instability in the presence of bleeding, and most of these patients do have a drop in hemoglobin concentration requiring blood transfusions.

Patients who may have an increased risk of stress gastritis are those with severe illness, major surgery, massive burn injury, head injury associated with raised intracranial pressure, sepsis and positive blood culture results, severe polytrauma 7 and multiple system organ failure 1. The clinician should have a high index of suspicion in patients in these settings who are noted to have decreased hematocrit values and who are not receiving prophylaxis for stress gastritis.

Some types of psychiatric stressors (eg, major, untreated depression) can cause stress gastritis 7.

Curling ulcer diagnosis

Before the diagnostic evaluation for stress ulceration, stabilization of the patients should take priority. Monitor the need for fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion and reversal of coagulopathy if needed. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed. Stress ulcers are seen as small superficial mucosal erosions or ulcerations in the gastric body and fundus.

Useful investigations and diagnostic tools include the following:

- Hematocrit level

- Coagulation profile

- Helicobacter pylori studies (eg, urease breath test, stool antigen test) for refractory stress ulceration

Curling’s ulcer treatment

Management of stress-induced gastritis includes prompt identification and prevention of complications related to stress ulceration. The management can be divided into pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

The nonpharmacological interventions include early enteral feeding, nasogastric tube placement intravenous fluid resuscitation, blood transfusion, and reversal of coagulopathy by platelets transfusion or transfusion of fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate 14.

The medical management of patients with stress ulcers is more or less similar to the management of peptic ulcer disease in general. The medication targeting acid peptic disease includes proton pump inhibitors, antihistaminic, and ulcer-healing drugs like sucralfate. Patients with overt gastrointestinal bleeding from ulceration will require endoscopic evaluation and management of the stress ulcers. Endoscopic therapies may include epinephrine injection, electro-cauterization, or clipping of the bleeding vessels. Bleeding ulcers refractory to localized endoscopic treatment may need embolization of the culprit vessel or rarely surgical intervention as a last resort. Surgical interventions are commonly indicated for patients with refractory bleeding despite endoscopic or angiographic treatment or patients with unstable hemodynamics to undergo endoscopic or angiographic procedures. Surgeries are performed as an ultimate life-saving approach 15.

Sometimes the ulcers can be deep enough to cause perforation of the gastric wall leading to acute peritonitis requiring urgent laparotomy. In comparison to other forms of stress ulcerations, perforations are most likely to happen with Cushing and Curling ulcers as they tend to be deep and can cause extensive necrosis. Mortality without surgical intervention in these patients who develop free wall gastrointestinal perforation is almost 100% 16.

Surgical care

In general, surgical interventions are for life-saving measures—such as refractory bleeding despite endoscopic or angiographic therapy, or in individuals who are hemodynamically unstable to undergo these procedures 1.

Surgical intervention may also be required in the setting of deep ulcers that lead to perforation of the gastric wall, resulting in acute peritonitis that necessitates urgent laparotomy 1.

Curling ulcer prognosis

Patients with stress ulceration usually have poor prognosis secondary to the underlying critical illness. Moreover, gastrointestinal bleeds in these patients secondary to stress-related mucosal disease is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality. More often, these patients are too unstable for advanced endoscopic or surgical procedures to suppress gastrointestinal bleed, leading to worse outcomes. Hence, aggressive prophylactic measures for the appropriate patient population at risk of developing stress ulceration remains the cornerstone in the management of stress-induced gastropathy 17.

- Siddiqui AH, Farooq U, Siddiqui F. Curling Ulcer (Stress-induced Gastric) [Updated 2020 Feb 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482347[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Stress-Induced Gastritis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176319-overview[↩]

- Siddiqui F, Ahmed M, Abbasi S, Avula A, Siddiqui AH, Philipose J, Khan HM, Khan TMA, Deeb L, Chalhoub M. Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A National Database Analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2019 Jan;11(1):42-48.[↩][↩]

- Kumar S, Ramos C, Garcia-Carrasquillo RJ, Green PH, Lebwohl B. Incidence and risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding among patients admitted to medical intensive care units. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul;8(3):167-173.[↩]

- Cheung LY. Thomas G Orr Memorial Lecture. Pathogenesis, prophylaxis, and treatment of stress gastritis. Am. J. Surg. 1988 Dec;156(6):437-40.[↩]

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb S, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R., Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including The Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Feb;39(2):165-228.[↩]

- Megha R, Farooq U, Lopez PP. Stress-Induced Gastritis. [Updated 2020 Feb 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499926[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Azab M, Doo L, Doo DH, et al. Comparison of the hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection risk of using proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2 receptor antagonists for prophylaxis and treatment of stress ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Liver. 2017 Nov 15. 11(6):781-8.[↩]

- Barletta JF, Bruno JJ, Buckley MS, Cook DJ. Stress ulcer prophylaxis. Crit Care Med. 2016 Jul. 44(7):1395-405.[↩]

- Alshamsi F, Belley-Cote E, Cook D, et al. Efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitors for stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care. 2016 May 4. 20 (1):120.[↩]

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R. Re-evaluating the utility of stress ulcer prophylaxis in the critically ill patient: a clinical scenario-based meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2018 Aug 13.[↩]

- Palm NM, McKinzie B, Ferguson PL, et al. Pharmacologic stress gastropathy prophylaxis may not be necessary in at-risk surgical trauma ICU patients tolerating enteral nutrition. J Intensive Care Med. 2018 Jul. 33(7):424-9.[↩][↩]

- Becq A, Urien S, Barret M, Faisy C. Epinephrine dose has a preventive effect on the occurrence of stress ulcer-induced gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Jun 12.[↩]

- Amaral MC, Favas C, Alves JD, Riso N, Riscado MV. Stress-related mucosal disease: incidence of bleeding and the role of omeprazole in its prophylaxis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2010 Oct;21(5):386-8.[↩]

- Enquist IF, Karlson KE, Dennis C, Fierst SM, Shaftan GW. Statistically valid ten-year comparative evaluation of three methods of management of massive gastroduodenal hemorrhage. Ann. Surg. 1965 Oct;162(4):550-60.[↩]

- Kanchan T, Geriani D, Savithry KS. Curling’s ulcer – have these stress ulcers gone extinct? Burns. 2015 Feb;41(1):198-9.[↩]

- Cho J, Choi SM, Yu SJ, Park YS, Lee CH, Lee SM, Yim JJ, Yoo CG, Kim YW, Han SK, Lee J. Bleeding complications in critically ill patients with liver cirrhosis. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2016 Mar;31(2):288-95.[↩]