Dracunculiasis

Dracunculiasis also known as Guinea worm disease, is caused by the nematode (roundworm) Dracunculus medinensis that is acquired by drinking water containing copepods (water fleas) infected with its larvae. Larvae are immature forms of the Dracunculus medinensis worm. The Dracunculus medinensis worm typically emerges through the skin on a lower limb approximately 1 year after infection, causing pain and disability 1. Dracunculiasis or Guinea worm disease affects poor communities in remote parts of Africa that do not have safe water to drink. Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is primarily a human disease. However, in recent years infections in animals, particularly in dogs, have been reported. As a result of research into the cause of Guinea worm infections in animals, it is now believed that Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) might also be spread to both animals and humans by eating certain aquatic animals that might carry Guinea worm larvae, like fish or frogs, but do not themselves suffer the effects of transmission.

Dracunculus medinensis worm is the largest of the tissue parasite affecting humans. The adult female, which carries about 3 million embryos, can measure 600 to 800 mm in length and 2 mm in diameter. The parasite migrates through the victim’s subcutaneous tissues causing severe pain especially when it occurs in the joints. The worm eventually emerges (from the feet in most of the cases), causing an intensely painful edema, a blister and an ulcer accompanied by fever, nausea and vomiting. Infected persons try to relieve the burning sensation by immersing the infected part of their body in local water sources, usually ponds water. This also induces a contraction of the female worm at the base of the ulcer causing the sudden expulsion of hundreds of thousands of first stage larvae into the water. They move actively in the water, where they can live for a few days.

For further development, these larvae need to be ingested by suitable species of voracious predatory crustacean, Cyclops or water fleas which measure 1–2 mm and widely abundant worldwide. In the cyclops, larvae develop to infective third-stage in 14 days at 26 °C.

When a person drinks contaminated water from ponds or shallow open wells, the cyclops is dissolved by the gastric acid of the stomach and the larvae are released and migrate through the intestinal wall. After 100 days, the male and female meet and mate. The male becomes encapsulated and dies in the tissues while the female moves down the muscle planes. After about one year of the infection, the female worm emerges usually from the feet releasing thousands of larvae thus repeating the life cycle.

Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) only occurs in the poorest 10% of the world’s population who have no access to safe drinking water or health care. Therefore, Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is both a disease of poverty and a cause of poverty 2. Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) can occur at any time of the year but occurs most commonly during peak transmission season, which varies from country to country. In dry regions, people generally get infected during the rainy season, when stagnant surface water is available. In wet regions, people generally get infected during the dry season, when surface water is drying up and becoming stagnant.

Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is rarely fatal. Frequently, however, the patient remains sick for several months, mainly because:

- The emergence of the worm, sometimes several, is accompanied by painful edema, intense generalized pruritus, blistering and an ulceration of the area from which the worm emerges.

- The migration and emergence of the worms occur in sensitive parts of the body, sometimes the articular spaces can lead to permanent disability.

- Ulcers caused by the emergence of the worm invariably develop secondary bacterial infections which exacerbate inflammation and pain resulting in temporary disability ranging from a few weeks to a few months.

- Accidental rupture of the worm in the tissue spaces can result in serious allergic reactions.

There is neither a drug treatment for Guinea worm disease nor a vaccine to prevent it. Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is considered by global health officials to be a neglected tropical disease and it is the first parasitic disease targeted for eradication. Great progress has been made towards elimination of dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease); the number of human cases annually has fallen from 3.5 million in the mid-1980s to 28 in 2018 3.

As of February 2019, the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication has certifiedexternal icon 199 countries, territories, and areas as being free from Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) transmission, with only 7 countries remaining to be certified: Angola, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Mali, South Sudan, and Sudan 4.

Thanks to the Guinea Worm Eradication Program, there were only 28 human cases reported worldwide in 2018. These human cases were reported in Angola (1 case), Chad (17 cases), and South Sudan (10 cases). Animals infected with D. medinensis, mostly domesticated dogs, have been reported since 2012. In 2018, Chad reported 1,040 infected dogs and 25 cats; Ethiopia reported 11 infected dogs, five cats, and one baboon; and Mali reported 18 infected dogs and two cats 5.

The mainstay of treatment is the extraction of the adult worm from the patient using a stick at the skin surface and wrapping or winding the worm a few centimeters per day. Because the worm can be as long as one meter in length, full extraction can take several days to weeks. This slow process is required to avoid breakage and leaving behind a portion of the worm.

Each day, the affected body part is immersed in a container of water to encourage more of the worm to come out. The wound is cleaned and gentle traction is applied to the worm to slowly pull it out. Pulling stops when resistance is met to avoid breaking the worm. The worm is wrapped around a stick to maintain some tension on the worm and encourage more of the worm to emerge. Topical antibiotics are applied to the wound to prevent secondary bacterial infections and the affected body part is then bandaged with fresh gauze to protect the site. These steps are repeated every day until the whole worm is successfully pulled out.

Dracunculiasis causes

Today, Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) affects poor communities in remote parts of Africa that do not have safe water to drink. People become infected with Guinea worm by drinking stagnant water containing copepods (tiny “water fleas” too small to be clearly seen without a magnifying glass) that carry Guinea worm larvae (immature forms of the worm). The larvae are swallowed by the copepods that live in these stagnant water sources. The larvae need about 2 weeks to mature inside the copepods before they can infect humans. Unsafe stagnant water includes ponds, pools in drying riverbeds, and shallow hand-dug wells without surrounding protective walls. Anyone who drinks from contaminated water sources can become infected. Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is not normally caught from drinking flowing water (rivers and streams) 6. Alternatively, persons who live in countries where Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is occurring (such as Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan) and consume raw or undercooked aquatic animals (such as small whole fish that have not been gutted, other fish, and frogs) might also be at risk for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) 7.

Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) transmission has a seasonal pattern. In dry regions, people generally get infected during the rainy season, when stagnant surface water is available. In wet regions, people generally get infected during the dry season, when surface water is drying up and becoming stagnant 8.

The risk for disease varies by sex, age, profession, and ethnicity. These differences reflect how and where people get their drinking water in different areas and countries. In general, about the same number of men and women get infected. Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) occurs in all age groups but it is most common among young adults 15–45 years old. This may be because of the type of work done by people this age. Farmers, herders, and those fetching drinking water for the household may be more likely to become infected, possibly because they drink contaminated stagnant water while away from home. In certain areas, Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) affects some ethnic groups more than others 9.

The greatest risk for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is having Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) the year before. People do not become immune to infection. Many people in affected villages suffer from Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) year after year. This is probably because the same water sources are repeatedly contaminated and conditions that support the spread of disease have not changed. It might also be related to some biological characteristic of the person that increases susceptibility. Not everyone drinking from the same contaminated water supply will become infected. A few people seem to keep getting infected while others drinking the same water do not 9.

Since 2012, an unusual epidemiologic pattern has been recognized in Chad. While the number of cases in humans has remained limited, there have been large numbers of cases recognized in dogs, particularly in the area along the Chari River. This has led to consideration of the possibility of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) transmission though a previously unrecognized route—consumption of fish, frogs, or other aquatic animals that carry Guinea worm larvae, but do not themselves suffer the effects of transmission 10. The situation is being carefully investigated 11 and control measures (tethering of dogs, education to remind area residents to fully cook food and not feed fish guts to dogs) have been implemented 7.

While most Guinea worm infections in animals have occurred in dogs and most dog infections have occurred in Chad, dog infections have occurred in other countries as well and Guinea worms have infected other types of animals too. In 2018, Chad reported 1,040 Guinea worm-infected dogs and 25 cats; Ethiopia reported 11 infected dogs, five cats, and one baboon; and Mali reported 18 infected dogs and two cats 12.

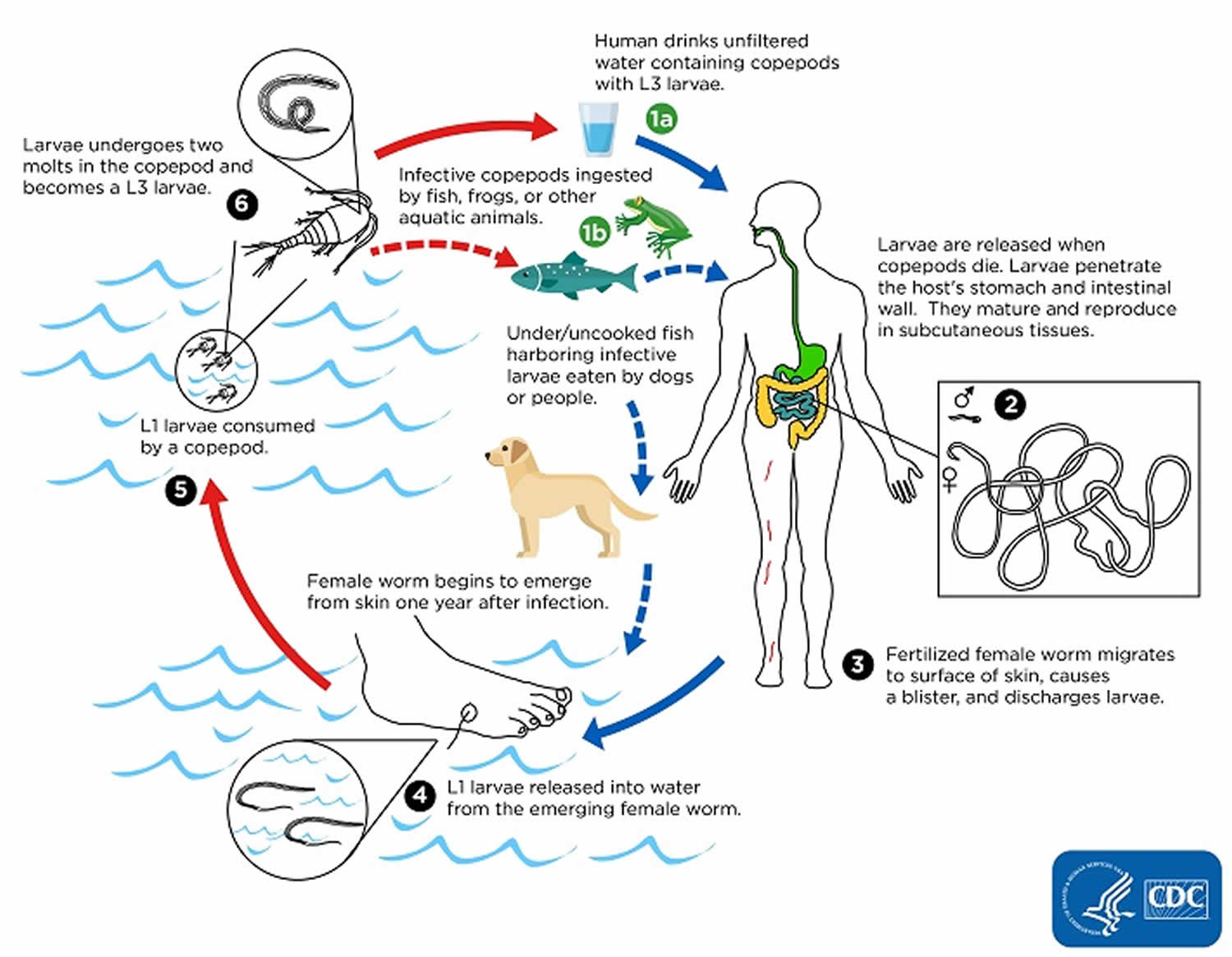

Dracunculiasis life cycle

Recent research has shown that certain aquatic animals can become infected by eating copepods (tiny “water fleas” too small to be clearly seen without a magnifying glass) that have been infected with Guinea worm larvae 13. Larvae are immature forms of the Guinea worm that contaminate water. Animals (e.g., dogs) and humans who live in countries where Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is occurring (such as Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan ) and consume raw or undercooked aquatic animals (such as small whole fish that have not been gutted, other fish, and frogs) may be at risk for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease).

Humans become infected by drinking unfiltered water containing copepods (small crustaceans) which are infected with larvae of Dracunculus medinensis (number #1). Following ingestion, the copepods die and release the larvae, which penetrate the host stomach and intestinal wall and enter the abdominal cavity and retroperitoneal space (number #2). After maturation into adults and copulation, the male worms die and the females (length: 70 to 120 cm) migrate in the subcutaneous tissues towards the skin surface (number #3). Approximately one year after infection, the female worm induces a blister on the skin, generally on the distal lower extremity, which ruptures. When this lesion comes into contact with water, a contact that the patient seeks to relieve the local discomfort, the female worm emerges and releases larvae (number #4). The larvae are ingested by a copepod and after two weeks (and two molts) have developed into infective larvae (number #5). Ingestion of the copepods closes the cycle (number #1).

Figure 1. Dracunculiasis life cycle

Dracunculiasis prevention

Teaching people to follow these simple control measures can prevent the spread of the Guinea worm disease:

- Drink only water from protected sources (such as from boreholes or protected hand-dug wells) that are free from contamination.

- If this is not possible, always filter drinking water from unsafe sources using a special Guinea worm cloth filter or a Guinea worm pipe filter to remove the copepods (tiny “water fleas” too small to be clearly seen without a magnifying glass) that carry the Guinea worm larvae. Unsafe water sources include stagnant water ponds, pools in drying riverbeds, and shallow hand-dug wells without surrounding protective walls.

- Cook fish and other aquatic animals (e.g., frogs) well before eating them. Bury or burn fish entrails left over from fish processing to prevent dogs from eating them. Avoid feeding fish entrails to dogs. Avoid feeding raw or undercooked fish or aquatic animals to dogs.

- Prevent people with blisters, swellings, wounds, and visible worms emerging from their skin from entering ponds and other water sources.

- Tether dogs that have blisters, swellings, wounds, and visible worms emerging from their skin to prevent the dogs from entering ponds and other water sources.

In addition to these health education measures, the Guinea Worm Eradication Program also undertakes the following two additional water-related measures to prevent Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease):

- Guinea Worm Eradication Program staff treat targeted unsafe drinking water sources at risk for contamination with Guinea worm larvae with the approved chemical temephos (ABATE®*) to kill the copepods and reduce the risk of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) transmission from that water source.

- Guinea Worm Eradication Program staff provide targeted communities at risk for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) with new safe sources of drinking water and repair broken safe water sources (e.g., hand-pumps) if possible.

Prevention of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is based on the following:

- Surveillance (case detection) and case containment (preventing contamination of drinking water sources by infected persons or animals)

- Provision of safe drinking water

- Vector control (killing of the copepods involved in the Guinea worm life cycle) using the approved chemical temephos

- Health education and community mobilization.

Many of these interventions are provided by village volunteers—people who are selected by the community to work with the Guinea Worm Eradication Program. Village volunteers are the backbone of the program. In their communities, they identify and manage people with Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) and prevent them from contaminating drinking water sources (case containment). They also distribute water filters and provide health education to the community.

Surveillance and case containment

Guinea Worm Eradication Program village volunteers look daily for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) cases in their communities. Every month they report the total number of cases detected in their communities to supervisors who compile this and send it to the national Guinea Worm Eradication Program headquarters. This information is then shared with The Carter Center and the World Health Organization (WHO). The Guinea Worm Eradication Program uses this information to identify where transmission is ongoing and to understand how the disease is spreading.

Case containment is one of the key methods used to prevent the spread of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). Case containment centers have been built in strategic locations in several countries 14. These centers provide treatment and support to people with Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) and help prevent them from contaminating water sources. A case of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is considered to be contained when 15:

- The person is identified within 24 hours of the worm emerging; AND

- The person has not entered any water source since the worm has emerged; AND

- The person receives proper treatment and case management by a local health provider, by cleaning and bandaging the wound until the worm has been fully removed manually and by providing health education to discourage the patient from contaminating any water source (if two or more emerging worms are present, transmission is not contained until the last worm is removed); AND

- Within seven days of the worm emerging, a Guinea Worm Eradication Program supervisor determines that the above criteria have been met and the case is truly Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease); AND

- The approved chemical temephos is used to treat potentially contaminated surface water if there is any uncertainty about contamination or if contamination was known to have occurred and if the water body in question meets certain other logistical criteria.

Safe Water

Safe drinking water sources include bore-hole wells and deep hand-dug wells with protective walls around them that prevent contaminated water from flowing back into the well (e.g., after rains or floods or if someone pours/spills water nearby the well). Flowing water, such as that found in a stream or river, is also safe from Guinea worm. The Guinea Worm Eradication Program advocates for the development and maintenance of safe drinking water sources. It also encourages treatment of potentially contaminated drinking water. Fine-mesh cloth filters are given to households to strain out copepods (tiny “water fleas” too small to be clearly seen without a magnifying glass) from contaminated drinking water where there are no safe water supplies. People who travel or work away from the household and might not have access to filtered water are given individual pipe filters. These devices are used like straws to drink water from unsafe water sources.

Vector control

A vector is an organism that carries or transmits disease. The vector for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) is the copepod. To control this vector, the Guinea Worm Eradication Program puts a measured amount of the approved chemical temephos (ABATE®) into the water sources that are suspected or known to be contaminated with Guinea worm-infected copepods. This chemical kills the infected copepods and prevents people from becoming infected with Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) when they drink the water.

Health education and community mobilization

Health education and community mobilization are important aspects of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication. Activities include the following:

- Teaching communities about the disease and how it is spread

- Educating people during household visits by Guinea Worm Eradication Program volunteers and staff and through organized events, such as Worm Weeks

- Helping villagers take action against the disease

- Preventing people with emerging worms from entering and contaminating drinking water supplies

- Using water filters to protect against Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease)

- Helping villagers understand the need for safe chemical treatment (temephos) in their water supplies

Dracunculiasis eradication

Many federal, private, and international agencies are helping with the eradication of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). During 2018, Angola and South Sudan reported human cases; Chad and Ethiopia reported both human and animal cases; and Mali reported animal cases. Human cases have fallen from 3.5 million per year in 1986 to 28 in 2018. Animals infected with D. medinensis, mostly domesticated dogs, have been reported since 2012. Most animal infections have occurred in Chad but some have been reported in Ethiopia and Mali.

Global eradication campaign

The global campaign to eradicate Guinea worm disease began in 1980 at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC suggested that the eradication of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) would be an ideal indicator of success for the United Nations International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (1981–1990) because it was believed that people could only get Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) by drinking contaminated water.

In 1986, there were 20 countries with Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). These countries had about 3.5 million human cases per year. Most (90%) cases occurred in Africa. An additional 120 million people in Africa were at risk for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) because of unsafe water supplies 6. That year, the World Health Assembly adopted a formal resolution calling for the elimination of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease), country by country 16. The Carter Center, working closely with Ministries of Health, took the lead for the global Guinea Worm Eradication Program in 1986 and built local, national, and international partnerships. Support came from numerous donor agencies, foundations, institutions, and governments. Based on the success of the Guinea Worm Eradication Program, the World Health Assembly adopted its first resolution to eradicate Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) from the world in 1991 10. A country has successfully interrupted transmission and eliminated Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) when there have been no reports of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) for three or more years 6. When all countries are certified by WHO as having eliminated Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) or never having had Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease), then global eradication will be achieved.

Criteria for eradication

World Health Assembly initially targeted Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) for eradication because it met the following specific criteria:

It was biologically and technically possible to eradicate this disease 8.

- There was no chance for the disease to return after the last human case occurs.

- Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) was easily diagnosed because of its signs and symptoms. Few diseases could be confused with Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) and the public in affected communities knew and recognized the worm.

- In each affected country the worms emerge from the skin during certain predicable times of the year.

- Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) was previously eliminated from parts of the Former Soviet Union during the 1920s and from endemic areas of Iran in the 1970s.

The benefits of eradication outweighed the costs 17.

- The World Bank assessed the socio-economic impact of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) in 1997. It concluded that the costs for Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication and morbidity reduction would be significantly less than the continued costs of the disease.

- Other direct benefits of eradication would include:

- The development of a group of trained health workers who could provide both Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) management and other basic health services.

- Improvements in water supplies

- Water no longer contaminated with Guinea worm

- Enhanced advocacy for new safe water sources

- The global community would indirectly benefit from the enhanced culture of disease prevention and social equity afforded by this disease eradication program. Countries and organizations supporting Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication would be helping to reduce the suffering of some of the world’s most underprivileged people.

While support for eradication was felt to be strong in endemic countries, there were political and societal barriers to eradication that were also considered by the World Health Assembly. Political support was and still is variable, even in endemic countries. International donor support was and is difficult to maintain for this neglected tropical disease. Neglected tropical diseases affect the poorest populations, including people living in remote rural areas or conflict zones who often have little political voice. Therefore, diseases such as Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) generally have a low profile and limited status in the list of public health priorities 9. Nevertheless, in 1986 and again 1991 the World Health Assembly adopted the resolution to eliminate and then eradicate Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease).

Criteria for certification of dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication

Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) transmission is interrupted in a country once no new Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) cases occur for 12 consecutive months (i.e., one incubation period). At this point, countries can apply for certification of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease)-free status from the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication 18.

The International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication is a panel of international Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) specialists. It was established by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1995 to verify and confirm information from countries applying for certification. The International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication considers Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication to be achieved in a country when:

- Adequate active surveillance systems have confirmed the absence of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) for 3 or more years;

- A rumor log of suspected cases has been maintained for a 3-year period detailing:

- The particulars of each case,

- The origin of each case, and

- The final diagnosis of each case (i.e., a true case of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) or some other condition); and

- All confirmed cases imported from endemic countries have been traced to their origins and have been fully contained.

The International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication certifies a country as being free from Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) after it confirms these criteria have been met and receives a report detailing the history of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) in that country 18.

With the discovery of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) in animals, mostly domestic dogs in Chad, the Guinea Worm Eradication Program has augmented its interventions to address possible spread by aquatic animals. These include health education about burying or burning fish entrails left over from fish processing to prevent dogs from eating them and avoiding feeding fish entrails to dogs. People are also advised to cook well any fish and other aquatic animals before eating them to prevent themselves from becoming infected. A reward is also offered for persons who report Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) in their dogs before the dogs can contaminate water; the reward helps cover the cost of tethering, feeding, and caring for the dog with the help of the Guinea Worm Eradication Program until the worm or worms are safely removed.

Transmission from a patient or animal with dracunculiasis is contained only if all of the following conditions are met for each emerged worm: 1) the infected patient or animal is identified before or within 24 hours after worm emergence; 2) the patient or animal has not entered any water source since the worm emerged; 3) a village volunteer or other health care provider has managed the patient or animal properly, by cleaning and bandaging the wound until the worm has been fully removed and by providing health education to the patient or the animal’s owner to discourage the patient or animal from contaminating any water source (if two or more emerging worms are present, transmission is not contained until the last worm is removed); 4) the containment process, including verification of dracunculiasis, is validated by a Guinea Worm Eradication Program supervisor within 7 days of emergence of the worm; and 5) the approved chemical temephos (ABATE®†) is used to kill the copepods if any uncertainty about contamination of sources of drinking water exists, or if a source of drinking water is known to have been contaminated 15.

Dracunculiasis symptoms

People with Dracunculiasis or Guinea worm disease have no symptoms for about 1 year. Then, the person begins to feel ill. Symptoms can include:

- Slight fever

- Itchy rash

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Dizziness

A blister then develops. This blister can form anywhere on the skin. However, the blister forms on the lower body parts in 80%–90% of cases. This blister gets bigger over several days and causes a burning pain. The blister eventually ruptures, exposing the worm. The infected person may put the affected body part in cool water to ease the symptoms or may enter water to perform daily tasks, such as fetching drinking water. On contact with water, the worm discharges hundreds of thousands of larvae into the water 19.

Disability

While the death rate is low, disability is a common outcome of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). People have difficulty moving around because of pain and complications caused by secondary bacterial infections. The disability that occurs during worm removal and recovery prevents people from working in their fields, tending animals, going to school, and caring for their families. Disability lasts 8.5 weeks on average but sometimes can be permanent. When Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) was more common, the negative impacts on farming and livestock tending caused financial losses in the millions of dollars each year. In some villages where infection rates were high, more than 60% of children missed school. Some children were disabled by infection. Other children needed to work in place of disabled family members 19.

Dracunculiasis complications

In addition to the pain of the blister, removing the Dracunculus medinensis worm is also very painful. Furthermore, without proper care the wound often becomes infected by bacteria. These wound infections can then result in one or more of the following complications:

- Redness and swelling of the skin (cellulitis)

- Boils (abscesses)

- Generalized infection (sepsis)

- Joint infections (septic arthritis) that can cause the joints to lock and deform (contractures)

- Lock jaw (tetanus)

If the Dracunculus medinensis worm breaks during removal it can cause intense inflammation as the remaining part of the dead worm starts to degrade inside the body. This causes more pain, swelling, and cellulitis 20.

Dracunculiasis diagnosis

The following laboratory studies are indicated in dracunculiasis:

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: The white blood cell count is likely elevated, even if only slightly. The differential commonly indicates eosinophilia.

- Serum immunoglobulin levels: Immunoglobulin E (IgE), immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), and immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) levels are usually elevated, with variability depending on the stage of disease. Patent infections (immediately following blister eruption but before ulcer formation) cause the greatest elevation of the 2 IgG subclasses, whereas both are relatively less elevated with postpatent (ulcerated) or prepatent (blister in formative stage) infections.

Imaging studies

A radiologic examination (plain-film roentgenography) of the lower extremity may prove useful in the identification of calcified worms in the rare case when surgery is considered. Incidental identification of calcified lesions from dracunculiasis has also been reported after radiographic evaluation of a painful lower extremity.

Dracunculiasis treatment

When the Guinea worm is ready to come out of the body, it creates a painful burning blister on the skin. The blister eventually ruptures, exposing the worm. Management of Guinea worm disease or Dracunculiasis involves removing the whole worm and caring for the wound in general. There is no specific drug to treat or prevent Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). There is also no vaccine to prevent Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease).

Optimal management of Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) involves the following steps 19:

- First, the infected person is not allowed to enter drinking water sources.

- Next, the wound is cleaned. The affected body part may be immersed or soaked in water (far away from any water source to prevent contamination) to encourage the worm to contract and release larvae. Emptying the worm of larvae may make removing the worm easier.

- The worm is then wrapped around a rolled piece of gauze or a stick to maintain some tension on the worm and encourage more of the worm to emerge. This also prevents the worm from slipping back inside.

- Then, gentle traction is applied to the worm to slowly pull it out. Pulling stops when resistance is met to avoid breaking the worm. Because the worm can be as long as one meter in length, full extraction can take several days to weeks.

- Afterwards, topical antibiotics are applied to the wound to prevent secondary bacterial infections.

- The affected body part is then bandaged with fresh gauze to protect the site. Medicines, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, are given to help ease the pain of this process and reduce inflammation.

- These steps are repeated every day until the whole worm is successfully pulled out.

Analgesics, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, are given to help ease the pain of this process and reduce inflammation.

No specific drug is used to treat dracunculiasis. Metronidazole or thiabendazole (in adults) is usually adjunctive to stick therapy and somewhat facilitates the extraction process. However, one study found that antihelminthic therapy was associated with aberrant migration of worms, resulting in infection in areas other than the lower extremity. Therefore, such medications should be used with caution.

- Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Eberhard ML, Roy SL, Weiss AJ. Progress toward global eradication of dracunculiasis, January 2016–June 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1327–31.[↩]

- Hopkins DR, Hopkins EM. Guinea Worm: The End in Sight. In: Medical and Health Annual, E. Bernstein ed. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., Chicago 1991:10–27.[↩]

- Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Weiss AJ, Roy SL, Zingeser J, Guagliardo SA. Progress Toward Global Eradication of Dracunculiasis — January 2017–June 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1265–1270. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a3[↩]

- Dracunculiasis eradication. https://www.who.int/dracunculiasis/certification/en/[↩]

- World Health Organization. Dracunculiasis Eradication: Global Surveillance Summary, 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 93(21): p. 305–20.[↩]

- Hopkins DR, et al., Update: Progress Toward Global Eradication of Dracunculiasis, January 2007-June 2008. MMWR, 2008.Oct 31;57(43): p. 1173–6.[↩][↩][↩]

- Watts, S.J., Dracunculiasis in Africa in 1986: its geographic extent, incidence, and at-risk population. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 1987. 37(1): p. 119–25.[↩][↩]

- Ruiz-Tiben, E. and D.R. Hopkins, Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication. Adv Parasitol, 2006. 61: p. 275–309.[↩][↩]

- Hopkins, D.R., et al., Dracunculiasis eradication: neglected no longer. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2008. 79(4): p. 474–9.[↩][↩][↩]

- World Health Assembly, Eradication of dracunculiasis, in 5.[↩][↩]

- Aylward, B., et al., When is a disease eradicable? 100 years of lessons learned. Am J Public Health, 2000. 90(10): p. 1515–20.[↩]

- Guinea Worm Epidemiology & Risk Factors. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/guineaworm/epi.html[↩]

- Eberhard ML, Yabsley MJ, Zirimwabagabo H, Bishop H, Cleveland CA, Maerz JC, Bringolf R, Ruiz-Tiben E. Possible Role of Fish and Frogs as Paratenic Hosts of Dracunculus medinensis, Chad. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016. 22(8): p. 1428–30. doi: 10.3201/eid2208.160043[↩]

- Hochberg N, Ruiz-Tiben E, Downs P, Fagan J, Maguire JH. The Role of Case Containment Centers in the Eradication of Dracunculiasis in Togo and Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2008. 79(5): p. 722–8.[↩]

- Hopkins DR, et al., Progress Toward Global Eradication of Dracunculiasis, January 2016–June 2017. MMWR, 2017 Dec 8. 66(48): p. 1327–31.[↩][↩]

- World Health Assembly, Elimination of dracunculiasis, in 21.[↩]

- Molyneux, D.H., D.R. Hopkins, and N. Zagaria, Disease eradication, elimination and control: the need for accurate and consistent usage. Trends Parasitol, 2004. 20(8): p. 347–51.[↩]

- World Health Organization, Criteria for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication, in WHO/FIL/96.187 Rev.1.[↩][↩]

- Ruiz-Tiben, E. and D.R. Hopkins, Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease) eradication. Adv Parasitol, 2006. 61: p. 275-309.[↩][↩][↩]

- Greenaway, C., Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease). CMAJ, 2004. 170(4): p. 495-500.[↩]