Elimination diet

An elimination diet also called “exclusion diet”, is used to learn whether or not certain foods may be causing your symptoms or making them worse. If they are, elimination diet also can become a way to treat these symptoms. For most people, food is more than a daily necessity. You get personal pleasure from it. You nurture your children with it. And sharing it around the table is at the heart of your family and social life. For some people, though, foods can cause distressing, even dangerous, reactions, or chronic ill health. Foods can upset people for many reasons. Having a food problem may restrict your food choices somewhat, but it doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy eating and sharing with family and friends.

Food hypersensitivity may be the first stage in the development of ‘allergic diseases’ such as atopic eczema 1. Food allergy may be an important factor in up to 20% of children with atopic eczema under 4 years 2. The incidence of food allergy is highest around the age of six to nine months. Many clinicians have found that elimination of specific foods found by food challenge to elicit symptoms can lead to significant improvement in eczematous symptoms 3. Challenges in people with food allergies can lead to eczematous lesions and infiltration of allergic inflammatory cells and animal studies have suggested that eczema may be caused by food allergies 4.

However, many food reactions in people with atopic eczema may not necessarily be mediated through immune reactions 5. As sensitization to food early in life may be a predisposing factor 6 it is important to investigate whether the elimination of dietary triggers could help to alleviate the symptoms of atopic eczema. The role of dietary factors in atopic eczema either as a cause or as a treatment, through the use of exclusion diets, remains unclear 2. Many trialists advocate double blind placebo controlled food challenges to establish whether a child has a true food allergy 7.

There is a vast amount of literature claiming that dietary elimination causes improvement of atopic eczema in some cases. However, much of the evidence fails to withstand close scrutiny 5.

There are three main types of dietary exclusion 5:

- The simple elimination of cow’s milk protein and egg;

- ‘The few foods’ diet (a diet in which all but a handful of foods is excluded) 8. One problem with the ‘few foods diet’ is poor adherence because the diet is so restrictive 9;

- The ‘elemental’ diet, more accurately described as a non‐macromolecular diet since ordinary foodstuffs are all avoided, and the participant receives a liquid diet which contains amino acids, carbohydrate, fat, minerals and vitamins. The palatability of the elemental formula is poor.

Many people, with or without their doctor’s or dietician’s help, experiment by excluding a particular food suspected of causing a reaction for a variable time. Most investigators would base elimination diets upon proven food allergies, either by challenge or serum food‐specific IgE antibodies exceeding specific diagnostic decision points 10.

The advantage of dietary interventions is that they may address one of the primary causes, as opposed to merely suppressing the symptoms, although there can be serious consequences to any dietary manipulation that leaves the individual deficient in calories, protein or minerals such as calcium 11. Avoidance of multiple foods is potentially hazardous and requires continued paediatric and dietary supervision 11.

The role of food is much debated in atopic eczema, but the allergenic relevance of some proteins seems to be important only in a small number of people, especially in the first years of life 12.

Elimination diet phases

There are four main steps to an elimination diet 13.

If a food causes you to have an immediate allergic reaction, such as throat swelling, a severe rash, or other severe allergy symptoms, seek medical care and avoid food challenges unless you are directly supervised by a physician.

Step 1 – Planning

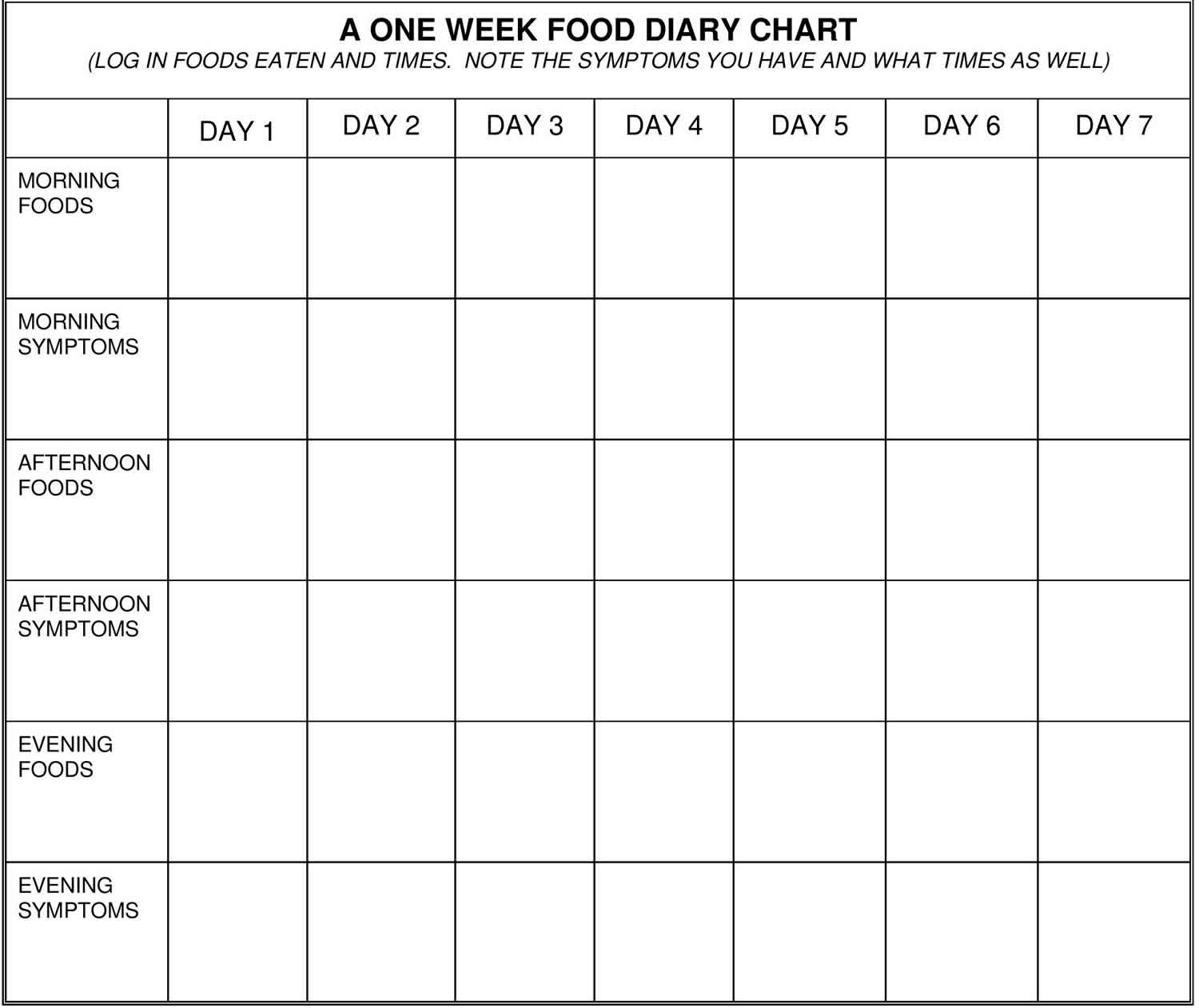

Work with your health care practitioner to learn which foods might be causing problems. You may be asked to keep a diet journal for a week, listing the foods you eat and keeping track of the symptoms you have throughout the day. It is helpful to ask yourself a few key questions:

- What foods do I eat most often?

- What foods do I crave?

- What foods do I eat to “feel better”?

- What foods would I have trouble giving up?

Often, these seem to be the foods that are most important to try not to eat. Table 1 lists the most common problem foods.

Table 1. Elimination diet food list

| Food group | Allowed | Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Meat, fish, poultry | chicken, turkey, lamb, cold water fishes | red meat, processed meats, eggs and egg substitutes Also avoid: Albumin, apovitellin, avidin, béarnaise sauce, eggnog, egg whites, flavoprotein, globulin, hollandaise sauce, imitation egg products, livetin, lysozyme, mayonnaise, meringe, ovalbuman, ovogycoprotin, ovomucin, ovomucoid, ovomuxoid, Simplesse. |

| Dairy | rice, soy and nut milks | milk, cheese, ice cream, yogurt Also avoid: Caramel candy, carob candies, casein and caseinates, custard, curds, lactalbumin, goats milk, milk chocolate, nougat, protein hydrolysate, semisweet chocolate, yogurt, pudding, whey. Also beware of brown sugar flavoring, butter flavoring, caramel flavoring, coconut cream flavoring, “natural flavoring,” Simplesse. |

| Legumes | all legumes (beans, lentils) | none |

| Vegetables | all | creamed or processed |

| Fruits | fresh or juiced | strawberries and citrus |

| Starches | potatoes, rice, buckwheat, millet, quinoa | gluten and corn containing products (pastas, breads, chips) |

| Breads/cereals | any made from rice, quinoa, amaranth, buckwheat, teff, millet, soy or potato flour, arrowroot | all made from wheat, spelt, kamut, rye, barley Also avoid: Atta, bal ahar, bread flour, bulgar, cake flour, cereal extract, couscous, cracked wheat, durum flour, farina, gluten, graham flour, high-gluten flour, high-protein flour, kamut flour, laubina, leche alim, malted cereals, minchin, multi-grain products, puffed wheat, red wheat flakes, rolled wheat, semolina, shredded wheat, soft wheat flour, spelt, superamine, triticale, vital gluten, vitalia macaroni, wheat protein powder, wheat starch, wheat tempeh, white flour, whole-wheat berries. Also beware of gelatinized starch, hydrolyzed |

| Soups | clear, vegetable-based | canned or creamed |

| Beverages | fresh or unsweetened fruit/vegetable juices, herbal teas, filtered/spring water | dairy, coffee/tea, alcohol, citrus drinks, sodas |

| Fats/oils | cold/expeller pressed, unrefined lightshielded canola, flax, olive refined oils, salad dressings, pumpkin, sesame, and walnut oils | margarine, shortening, butter, and spreads |

| Nuts/seeds | almonds, cashews, pecans, flax, pumpkin, sesame, sunflower seeds, and butters from allowed nuts | peanuts, pistachios, peanut butter Also avoid: Egg rolls, “high-protein food,” hydrolyzed plant protein, hydrolyzed vegetable protein, marzipan, nougat, candy, cheesecake crusts, chili, chocolates, pet food, sauces. |

| Sweeteners | brown rice syrup, fruit sweeteners | brown sugar, honey, fructose, molasses, corn syrup |

| Soy | Chee-fan, ketjap, metiauza, miso, natto, soy flour, soy protein concentrates, soy protein shakes, soy sauce, soybean hydrolysates, soby sprouts, sufu, tao-cho, tao-si, taotjo, tempeh, textured soy protein, textured vegetable protein, tofu, whey-soy drink. Also beware of hydrolyzed plant protein, hydrolyzed soy protein, hydrolyzed vegetable protein, natural flavoring, vegetable broth, vegetable gum, vegetable starch. |

Footnote:

- If you are using the elimination diet for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), consider eliminating the following foods for two weeks: dairy (lactose), wheat (gluten), high fructose corn syrup, sorbitol (chewing gum), eggs, nuts, shellfish, soybeans, beef, pork, lamb.

- If you are allergic to latex, you may also react to: apple, apricot, avocado, banana, carrot, celery, cherry, chestnut, coconut, fig, fish, grape, hazelnut, kiwi, mango, melon, nectarine, papaya, passion fruit, peach, pear, pineapple, plum, potato, rye, shellfish, strawberry, tomato and wheat.

Figure 1. Food Diary Chart

Step 2 – Avoiding

For two weeks, follow the elimination diet without any exceptions. Don’t eat the foods whole or as ingredients in other foods. For example, if you are avoiding all dairy products, you need to check labels for whey, casein, and lactose so you can avoid them as well. This step takes a lot of discipline. You must pay close attention to food labels. Be particularly careful if you are eating out, since you have less control over what goes into the food you eat.

Many people notice that in the first week, especially in the first few days, their symptoms will become worse before they start to improve. If your symptoms become severe or increase for more than a day or two, consult your health care practitioner.

Step 3 – Challenging

- If your symptoms have not improved in two weeks, stop the diet and talk with your health care practitioner about whether or not to try it again with a different combination of foods.

- If your symptoms improve, start “challenging” your body with the eliminated foods, one food group at a time. As you do this, keep a written record of your symptoms.

To challenge your body, add a new food group every three days. It takes three days to be sure that your symptoms have time to come back if they are going to. On the day you try an eliminated food for the first time, start with just a small amount in the morning. If you don’t notice any symptoms, eat two larger portions in the afternoon and evening. After a day of eating the new food, remove it, and wait for two days to see if you notice the symptoms.

If a food doesn’t cause symptoms during a challenge, it is unlikely to be a problem food and can be added back into your diet. However, don’t add the food back until you have tested all the other foods on your list.

Table 2. Example of an Elimination Diet Calendar

| Day Number | Step |

|---|---|

| 1 | Begin Elimination Diet |

| 2 to 7 | You may notice symptoms worse for a day or two |

| 8 to 14 | Symptoms should go away if the right foods have been removed |

| 15 | Re-introduce food #1 (for example, dairy) |

| 16 -17 | Stop food #1 and watch for symptoms* |

| 18 | Re-introduce food #2 (for example, wheat) |

| 19-20 | Stop food #2 again and watch for symptoms |

| 21 | Re-introduce food #3 |

| ….And so on |

Footnote: *You only eat a new food for one day. Do not add it back into your meal plan again until the elimination diet is over.

Step 4 – Creating A New, Long-Term Diet

Based on your results, your health care practitioner can help you plan a diet to prevent your symptoms. Some things to keep in mind:

- This is not a perfect test. It can be confusing to tell for certain if a specific food is the cause. A lot of other factors (such as a stressful day at work) could interfere with the results. Try to keep things as constant as possible while you are on the diet.

- Some people have problems with more than one food.

- Be sure that you are getting adequate nutrition during the elimination diet and as you change your diet for the long-term. For example, if you give up dairy, you must supplement your calcium from other sources like green leafy vegetables.

- You may need to try several different elimination diets before you identify the problem foods.

Modified elimination diet (dairy and gluten free)

The most common food proteins that can cause intolerance are cow’s milk protein and gluten from wheat. A modified elimination diet removes dairy and gluten and any other specific foods that may be craved or eaten a lot.

- Eliminate all dairy products, including milk, cream, cheese, cottage cheese, yogurt, butter, ice cream, and frozen yogurt.

- Eliminate gluten, avoiding any foods that contain wheat, spelt, kamut, oats, rye, barley, or malt. This is the most important part of the diet. Substitute with brown rice, millet, buckwheat, quinoa, gluten-free flour products, or potatoes, tapioca and arrowroot products.

Other foods to Eliminate

- Eliminate fatty meats like beef, pork, or veal. It is OK to eat the following unless you know that you are allergic or sensitive to them:

- chicken, turkey, lamb, and cold-water fish such as salmon, mackerel, sardines and halibut. Choose organic/free-range sources where available.

- Avoid alcohol and caffeine and all products that may contain these ingredients (including sodas, cold preparations, herbal tinctures).

- Avoid foods containing yeast or foods that promote yeast overgrowth, including processed foods, refined sugars, cheeses, commercially prepared condiments, peanuts, vinegar and alcoholic beverages.

- Avoid simple sugars such as candy, sweets and processed foods.

- Drink at least 2 quarts of water per day.

Eczema elimination diet

Atopic eczema is a non‐infective chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by an itchy red rash. The terms ‘atopic eczema’ and ‘atopic dermatitis’ are used synonymously. “Atopy” refers to a form of allergy in which there is a heritable tendency to develop “IgE” hypersensitivity reactions. However up to 40% of children with atopic eczema are not atopic, when defined according to allergy tests such as skin prick tests 14. Others have found that up to two thirds of people with atopic dermatitis are not atopic 15, implying that continued use of the term ‘atopic dermatitis’ is problematic.

A revised nomenclature for allergy 16 has been updated by the World Allergy Organization 17. The new nomenclature is based on the mechanisms that initiate and mediate allergic reactions. The term ‘eczema’ is proposed to replace the provisional term ‘atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome’ 17. What is generally known as ‘atopic eczema/dermatitis’ is probably not one single disease but rather an aggregation of several diseases with certain characteristics in common. The term ‘atopy’ cannot be used until an IgE sensitization has been documented by IgE antibodies in the blood of a person or by a positive skin prick test to common environmental allergens such as pollen, house dust mite, cow’s milk or egg. If this is done then the term ‘eczema’ can be split into ‘atopic eczema’ and ‘non‐atopic eczema’.

Atopic eczema is the most common inflammatory skin disease of childhood in developed countries, affecting 15 to 20% of children in the UK at any one time 18. Two‐thirds of people with the disease have a family history of atopic eczema, asthma or hay fever. The cumulative prevalence of atopic dermatitis varies from 20% in Northern Europe and the USA to 5% in the South‐Eastern Mediterranean 19. Prevalence data for the symptoms of atopic eczema were collected in the global International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood study. The results of this study suggest that atopic eczema is a worldwide problem affecting 15 to 20% of children 20. Of those children with atopic eczema, only 2% under the age of 5 years have severe disease and 84% have mild disease 21. Two per cent of adults have atopic eczema and many of these have a more chronic and severe form 22.

Atopic eczema is often associated with other atopic diseases e.g. asthma and rhinitis 23. The incidence of common allergic disease has increased in the past 30 years 24 and the increase in prevalence of atopic disease in the past 3 decades appears to be a real phenomenon and has been observed in countries as far apart as Japan, USA, Finland and Africa 25. The cause of atopic eczema is not well understood and is probably due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors 26. In recent years research has pointed to the possible role of environmental agents such as house dust mite 27, pollution 28, and prenatal or early exposure to infections 29. Food allergy may be common in atopic eczema especially if the eczema is severe 30.

Clinical features

Atopic eczema may be acute (short and severe) with redness, scaling, oozing and vesicles, or it may be chronic (long‐term) with skin thickening, altered pigmentation and exaggerated surface markings. The condition affects mainly the creases of the elbows and knees, and the face and neck, although it can affect any part of the body. The severity of eczema is variable, ranging from localised mild scaling to generalised involvement of the whole body with redness, oozing and secondary infection. Itching is the predominant symptom which can induce a vicious cycle of scratching, leading to skin damage, which in turn leads to more itching ‐ the so called “itch scratch itch” cycle. There is a tendency to a dry sensitive skin even in those who have ‘grown out’ of the disease. This is thought to be due to a defect in the lipid barrier of the epidermis. In adulthood, the skin (especially of the hands) may be prone to inflammation in the presence of environmental irritants such as soaps 31.

Natural history

Atopic eczema usually starts within the first 6 months of life, and by 1 year, 60% of those likely to develop it will have done so. Remission occurs by the age of 15 years, in 60 to 70% of cases, although some relapse later. In the more severely affected child, development and puberty may be delayed 32. Many children with eczema go on to develop asthma and hay fever, which might also be triggered by food allergy 33.

Impact

Atopic eczema varies in severity, often from one hour to the next. Severity can be measured in a number of ways. A systematic review of named outcome scales for atopic eczema found that of the 13 named scales in current use, only one (Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis, SCORAD) had been fully tested for validity, repeatability and responsiveness 34. Itching and scratching can adversely affect quality of life through chronic sleep disturbance. This may have an impact on family life. The disease can be associated with complications such as bacterial and viral infections 35. The unsightly appearance of the skin and the need to apply greasy ointments can limit a child’s inclination to participate in social and sporting activities and thus affect their confidence. Adults with atopic eczema often have low self‐esteem and relationships can be difficult to initiate and sustain. Everyday tasks such as housework, gardening, childcare and food preparation present problems when the skin on the hands is cracked. Promotion at work may be blocked for people who do not ‘look good’.

Atopic eczema treatment

There is currently no cure for atopic eczema. However a wide range of treatments are employed which aim to control the symptoms 36. Health professionals assist people in the management of their disease using a variety of treatment methods; these include emollients, topical steroids, topical tars, topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus. Other treatments such as wet wrap dressings, phototherapy and complementary therapies are also tried 37. Many of the treatments are of unknown effectiveness 18. Emollients and topical corticosteroids are universally recommended 38.

Elimination diet and atopic eczema

Many people try to relieve their eczema symptoms by avoiding certain foods. This is referred to as an “elimination diet”. Foods often associated with eczema include eggs, milk, fish and peanuts. Sugar and foods containing gluten, on the other hand, don’t play any role in the development of eczema. Sometimes, an elimination diet excludes more than just one or two types of food. But excluding certain foods is only a good idea if you’ve been diagnosed as being allergic to those specific foods (targeted elimination diet) 39.

It’s usually very hard to stick to a diet that isn’t targeted. And it’s often particularly difficult for children if they have to go without things like cake or other goodies. Small children may find it difficult to understand why they can’t eat certain things that other children are allowed to eat. It is important that people who are on elimination diets make sure that they still get enough nutrients, minerals and vitamins.

It’s difficult to find out whether eczema is being caused by a certain substance because the severity of eczema symptoms varies over time. You might easily get the idea that a specific food triggered a flare-up although the symptoms might have got worse on their own anyway. So eczema flare-ups are often mistakenly associated with certain foods.

It’s not proven that the arbitrary elimination of some foods can relieve eczema symptoms in children who don’t have a confirmed food allergy 39. There has been very little good-quality research on elimination diets in adults with eczema 39.

Testing for food allergies

Different tests can be used to find out whether someone has allergic (atopic) eczema. The most common are a skin prick test for allergies and a blood test IgE antibodies.

Both tests have limitations though. If the results are normal, you can be quite sure that you don’t have an allergy. Abnormal results are more difficult to interpret. They do show that the body is sensitive to the food. But the test can’t tell us whether it is causing the eczema or making the symptoms worse. Also, most people react to some substances in these kinds of tests. But that does not automatically mean that they have trouble in their everyday life too.

Because allergy testing gives us such limited results, Dermatological Society recommends them only if you are thought to have a specific allergy. The test results also need to be interpreted with caution: Abnormal test results are no reason to exclude one food. It’s different if a test called the “challenge” test confirms that the skin actually reacts to a certain food.

Research on elimination diets for eczema

Good scientific studies are needed to be able to find out whether or not elimination diets are effective for eczema. Such studies look at what happens when people who have eczema leave certain foods out of their diets. To do this, volunteers with eczema are randomly assigned to two groups. The research participants in one group are asked to keep eating their usual diets, while those in the other group are asked to go on a special diet.

Researchers from the Cochrane Collaboration 40 analyzed nine suitable studies that tested whether elimination diets had any effect on eczema symptoms. Six of the studies looked at diets that avoided eggs and milk. Two of them tested the effect of a liquid baby food reduced to a few nutrients without any allergens. One study looked at a diet made up of only a few foods. The participants were tested for food allergies in only one of these studies.

Most of the studies involved infants and children as participants. Only one involved adults exclusively. The studies were relatively small – the average number of participants was between 11 and 85. All of the studies also had weaknesses: For example, in some of them the participants did not stick to the strict diet properly. Only two studies followed the participants for longer than six months. In half the diets that excluded milk, soy-based milk substitutes were used. This could limit the value of the study outcomes because other research has shown that soy milk can sometimes cause allergies itself.

Elimination diets probably only help in people who have a diagnosed food allergy

In 8 of the 9 studies there was no clear difference between the groups of people who were on a special diet and those who were not. Most of the participants hadn’t been tested to see whether they had a food allergy in the first place, though. Generally eliminating foods you are not thought to be allergic to probably doesn’t help.

One of the studies looked at babies who had been found to have an allergic reaction to eggs based on a blood test done before the study started. In this study one group of babies had an egg-free diet for four weeks, whereas the other group had a normal diet. The results showed that not eating eggs reduced rashes in the babies, but there were only 62 of them included in the study.

Cochrane Collaboration Authors’ conclusions

There may be some benefit in using an egg‐free diet in infants with suspected egg allergy who have positive specific IgE to eggs 40. Little evidence supports the use of various exclusion diets in unselected people with atopic eczema, but that may be because they were not allergic to those substances in the first place. Lack of any benefit may also be because the studies were too small and poorly reported. Future studies should be appropriately powered focusing on participants with a proven food allergy. In addition a distinction should be made between young children whose food allergies improve with time and older children/adults.

Food allergy

Food allergy is an abnormal reaction to a food triggered by your body’s immune system (the part of your body that fights infection). The reaction can be serious or mild. Food intolerance is different than a food allergy. Food intolerance is an unpleasant symptom triggered by food (bloating, gas, stomach cramps). However, it does not involve your immune system.

If you have a food allergy, your immune system overreacts to a particular protein found in that food. Symptoms can occur when coming in contact with just a tiny amount of the food.

Many food allergies are first diagnosed in young children, though they may also appear in older children and adults.

Eight foods are responsible for the majority of allergic reactions:

- Cow’s milk

- Eggs

- Fish

- Peanuts

- Shellfish

- Soy

- Tree nuts

- Wheat

In adults, the foods that most often trigger allergic reactions include fish, shellfish, peanuts, and tree nuts, such as walnuts. Problem foods for children can include eggs, milk, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, and wheat.

The allergic reaction may be mild. In rare cases it can cause a severe reaction called anaphylaxis. Symptoms of food allergy include:

- Itching or swelling in your mouth

- Vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal cramps and pain

- Hives or eczema

- Tightening of the throat and trouble breathing

- Drop in blood pressure

Many people who think they are allergic to a food may actually be intolerant to it (food intolerance). The most classic food intolerances (such as lactose intolerance) cause patients to have bloating, fullness, belly pain, gas and/or diarrhea when they eat too much of the food. This is because the body is not properly digesting the food, which leads to build up of air and gas in the stomach and intestines. Other patients feel like they get headaches, fatigue, “brain fog” or belly pain with various foods or additives / preservatives. Many times, patients feel like multiple foods may be causing these symptoms and are hopeful to find a single test that will tell them exactly which foods to avoid so that they can simply feel better.

Some of the symptoms of food intolerance and food allergy are similar, but the differences between the two are very important. If you are allergic to a food, this allergen triggers a response in the immune system. Food allergy reactions can be life-threatening, so people with this type of allergy must be very careful to avoid their food triggers.

Being allergic to a food may also result in being allergic to a similar protein found in something else. For example, if you are allergic to ragweed, you may also develop reactions to bananas or melons. This is known as cross-reactivity. Cross-reactivity happens when the immune system thinks one protein is closely related to another. When foods are involved it is called oral allergy syndrome.

Food allergy can strike children and adults alike. While many children outgrow a food allergy, it is also possible for adults to develop allergies to particular foods.

Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES), sometimes referred to as a delayed food allergy, is a severe condition causing vomiting and diarrhea. In some cases, symptoms can progress to dehydration and shock brought on by low blood pressure and poor blood circulation.

Much like other food allergies, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) allergic reactions are triggered by ingesting a food allergen. Although any food can be a trigger, the most common culprits include milk, soy and grains. Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES) often develops in infancy, usually when a baby is introduced to solid food or formula.

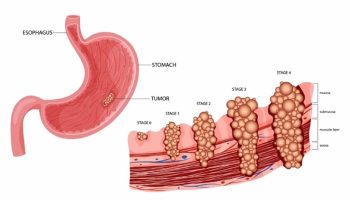

Eosinophilic esophagitis is an allergic condition causing inflammation of the esophagus. The esophagus is the tube that sends food from the throat to the stomach. Most research suggests that the leading cause of eosinophilic esophagitis is an allergy or a sensitivity to particular proteins found in foods. Many people with eosinophilic esophagitis have a family history of allergic disorders such as asthma, rhinitis, dermatitis or food allergy.

Your health care provider may use a detailed history, elimination diet, and skin and blood tests to diagnose a food allergy.

When you have food allergies, you must be prepared to treat an accidental exposure. Wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace, and carry an auto-injector device containing epinephrine (adrenaline).

You can only prevent the symptoms of food allergy by avoiding the food. After you and your health care provider have identified the foods to which you are sensitive, you must remove them from your diet.

What causes food allergies?

Although people can be allergic to any kind of food, most food allergies are caused by tree nuts, peanuts, milk, eggs, soy, wheat, fish, and shellfish. These 8 foods account for 90 percent of food allergies. Most people who have food allergies are allergic to fewer than four foods.

Additionally, studies have found that some food additives, such as yellow food dye and aspartame (artificial sweetener), do cause problems in some people. Sugar and fats are not associated with food allergies.

Can food allergies be prevented or avoided?

Once a food allergy is diagnosed, avoid the food that caused it. If you have an allergy, you must read the labels on all the prepared foods you eat. Your doctor can help you learn how to avoid eating the wrong foods. If your child has food allergies, give his or her school and other care providers instructions that list what foods to avoid. Tell them what to do if the food is accidentally eaten. There is no cure for food allergy.

Food allergy symptoms

Symptoms of a food allergy are usually immediate. The most common immediate symptoms of food allergy include:

- hives (large bumps on the skin)

- swelling

- itchy skin

- itchiness or tingling in the mouth

- metallic taste in the mouth

- coughing, trouble breathing, or wheezing

- throat tightness

- diarrhea

- vomiting.

The person may also feel that something bad is going to happen, have pale skin (because of low blood pressure), or lose consciousness. The most common chronic illnesses associated with food allergies are eczema (skin disorder) and asthma (respiratory disorder).

A food allergy can be deadly if it is severe enough to cause a reaction called anaphylaxis. This reaction blocks your airway and makes it hard for you to breathe.

How is a food allergy diagnosed?

If you have had an abnormal reaction to a food, see an allergist or immunologist, often referred to as an allergist, a doctor with specialized training and expertise to determine if your symptoms are caused by a food allergy or due to other food-related disorders such as food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) or eosinophilic esophagitis. Your allergist will examine your symptoms, ask about your medical history, followed by a physical examination. You will be asked about the foods you eat, the frequency, severity and nature of your symptoms, and the amount of time between eating a food and any reaction.

Allergy skin tests may determine which foods, if any, trigger your allergic symptoms. In skin testing, a small amount of extract made from the food is placed on the back or arm. If a raised bump or small hive develops within 20 minutes, it indicates a possible allergy. If it does not develop, the test is negative. It is uncommon for someone with a negative skin test to have an IgE-mediated food allergy.

In certain cases, such as in patients with severe eczema, an allergy skin test cannot be done. Your doctor may recommend an IgE blood test. False positive results may occur with both skin and blood testing. IgG blood testing is not recommended, as it is unproven in diagnosing food allergies. Oral food challenges can confirm the diagnosis and are done by consuming the food in a medical setting to determine if it causes a reaction. Food challenges should not take place at home.

Your allergist may put you on an elimination diet (where you take all suspicious foods out of your diet and gradually add them back one at a time), and perform skin and blood tests.

Many children usually outgrow allergies to milk, eggs, soybean products, and wheat. People rarely outgrow allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, fish, and shellfish.

A test that claims to be able to diagnose food sensitivities and is commonly available is the food IgG test. This test, offered by various companies, reports IgG levels to multiple foods (usually 90 to 100 foods with a single panel test) claiming that removal of foods with high IgG levels can lead to improvement in multiple symptoms. Some websites even report that diets utilizing this test can help with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, autism, cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis and epilepsy.

It is important to understand that this test has never been scientifically proven to be able to accomplish what it reports to do. The scientific studies that are provided to support the use of this test are often out of date, in non-reputable journals and many have not even used the IgG test in question. The presence of IgG is likely a normal response of the immune system to exposure to food. In fact, higher levels of IgG4 to foods may simply be associated with tolerance to those foods.

Due to the lack of evidence to support its use, many organizations, including the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology 41, the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 42 and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 43 have recommended against using IgG testing to diagnose food allergies or food intolerances / sensitivities.

It is understandably frustrating while looking for ways (especially natural, non-medicinal ways) to feel better, but patients need to know if the advice they are following is based on tests that have been proven or on tests that are controversial and have not been proven. Before someone severely alters their lifestyle and diet, they should have some comfort in knowing that they are doing so based on proper advice. An allergist or immunologist is able to provide you with this advice and can help you properly diagnose and manage your condition. Find an Allergist / Immunologist here: https://allergist.aaaai.org/find

Food allergy treatment

There is currently no cure for a food allergy, but there are many promising treatments under investigation. Avoidance, education and preparedness are the keys to managing food allergy. Your doctor will give you antihistamines and oral or topical steroid medicine if you have a mild reaction (itching, sneezing, hives, or rash). A more severe reaction would be treated with a medicine called epinephrine. This medicine must be given quickly to save your life. If you or your child has a severe allergy, your doctor might give you a prescription for an epinephrine pen to carry with you at all times. Your doctor can show you how and when to inject yourself with the pen. A person having an allergic reaction should be taken by ambulance to a hospital emergency room, because the amount of adrenaline being pumped into the body can be dangerous. A doctor can provide medicines to help slow a person’s blood circulation, breathing, and metabolism.

While exposure to airborne food allergens (e.g., from cooking vapors) usually does not result in anaphylaxis, it can cause a runny nose and itchy eyes similar to a reaction from coming in contact with pollen. However, eating even a small amount of the food, such as that left on cooking utensils or from a food processing facility, can cause a life-threatening reaction. This is why reading the ingredients on food labels and asking questions about prepared foods are an essential part of avoidance plans.

People with food allergy should always carry auto-injectable epinephrine to be used in the event of an anaphylactic reaction. Symptoms of anaphylaxis may include difficulty breathing, dizziness or loss of consciousness. If you have any of these symptoms in the context of eating, use the epinephrine auto-injector and immediately call your local emergency services number. Don’t wait to see if your symptoms go away or get better on their own.

Outgrowing food allergies

Most children outgrow their allergies to cow’s milk, egg, soy and wheat, even if they have a history of a severe reaction. However,peanut, tree nut fish and shellfish allergy tends to persist through adulthood. Repeat allergy testing with your allergist can help you learn when you or your child’s food allergies are resolving with time.

Living with food allergies

Living with food allergies can cause fear and anxiety when you are eating at a restaurant or someone else’s home. You will always wonder if your problem food combined with the rest of the meal. Also, if you have food allergies to most of the 8 common foods, you can feel frustrated by the restrictions in your life.

Healthy Tips

- Always ask about ingredients when eating at restaurants or when you are eating foods prepared by family or friends.

- Carefully read food labels. The United States and many other countries require that major food allergens are to be listed in common language (milk, egg, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, wheat, peanuts and soybeans).

- Carry and know how to use auto-injectable epinephrine and antihistamines to treat emergency reactions. Teach family members and other people close to you how to use epinephrine and consider wearing a medical alert bracelet that describes your allergy. If a reaction occurs, have someone take you to the emergency room, even if symptoms subside. Afterwards, get follow-up care from your allergist.

Food allergy elimination diet

The most common food allergens are the proteins in cow’s milk, eggs, peanuts, wheat, soy, fish, shellfish and tree nuts. In some food groups, especially tree nuts and seafood, an allergy to one member of a food family may result in the person being allergic to other members of the same group. This is known as cross-reactivity. Cross-reactivity for other food families is not common.

Most food allergens can cause allergic reactions even after they are cooked or have undergone digestion in the intestines, although research is showing that more than half of children with milk and egg allergies can tolerate extensively heated milk and egg in baked foods. Some allergens (usually fruits and vegetables) cause allergic reactions in people with a pollen allergy but only if eaten in raw form. Symptoms in these cases are usually limited to the mouth and throat.

Most symptoms of food allergy occur within 2 hours at the most, but within the past few years a new type of food allergy has been discovered called alpha gal, with symptoms that may be delayed by 4-8 hours, often awakening the person at night. This allergy is to galactose-alpha, 1,3-galactose, a carbohydrate found on mammalian meat, and is associated with being bitten by the Lone Star tick. People with alpha gal allergy should avoid beef, lamb, pork and venison.

- Chandra RK. Food hypersensitivity and allergic diseases. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2002;56 Suppl 3:S54‐6.[↩]

- Oranje AP, Waard‐van der Spek FB. Atopic dermatitis and diet. [comment]. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology 2000;14(6):437‐8.[↩][↩]

- Sampson HA. The evaluation and management of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Clinics in Dermatology 2003;21:183‐92.[↩]

- Li XM, Kleiner GA, Huang CK, Lee SY, Schofield BH, Soter NA. Murine model of atopic dermatitis associated with food hypersensitivity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001;107(4):693‐702.[↩]

- David TJ, Patel L, Ewing CI, Stanton RHJ. Dietary factors in established atopic dermatitis. In: Hywel Williams editor(s). Atopic Dermatitis. The epidemiology, causes and prevention of atopic eczema. Cambridge University Press, 2000:193‐201.[↩][↩][↩]

- Baena‐Cagnani CE, Teijeiro A. Role of food allergy in asthma in childhood. Current Opinion in Allergy & Clinical Immunology 2001;1(2):145‐9.[↩]

- Sampson HA. The immunopathogenic role of food hypersensitivity in atopic dermatitis. Acta Dermato Venereologica Supplementum 1992;176:34‐7.[↩]

- David TJ. Food and Food Additive Intolerance in Childhood. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1993.[↩]

- Devlin J, Stanton RHJ, David TJ. Calcium intake and cows’ milk free diets. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1989;64:1183‐4.[↩]

- Sampson HA. Utility of food‐specific IgE concentrations in predicting symptomatic food allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2001;107(5):891‐6.[↩]

- David TJ, Waddington E, Stanton RHJ. Nutritional hazards of elimination diets in children with atopic eczema. Archives of disease in childhood 1984;59:323‐5.[↩][↩]

- Svejgaard E, Jakobsen B, Svejgaard A. Studies of HLA‐ABC and DR antigens in pure atopic dermatitis and atopic dermatitis combined with allergic respiratory disease. Acta Dermato Venereologica Supplementum 1985;114:72‐6.[↩]

- Elimination Diet. University of Wisconsin Integrative Medicine. https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/file/11270/handout_elimination_diet_patient.pdf[↩]

- Bohme M, Svensson A, Kull I, Nordvall SL, Wahlgren CF. Clinical features of atopic dermatitis at two years of age: a prospective, population‐based case‐control study. Acta Dermato Venereologica 2001;81(3):193‐7.[↩]

- Flohr C, Johansson SGO, Wahlgren C‐F, Williams H. How atopic is atopic dermatitis?. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2004;114:150‐8.[↩]

- Johansson SGO, O’B Hourihane J, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel‐Koomen C, Dreborg S, Haahtela T. A revised nomenclature for allergy: an EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy 2001;56:813‐24.[↩]

- Johansson SGO, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2004;113:832‐6.[↩][↩]

- Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams H. Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technology Assessment 2000;4(37):1‐191.[↩][↩]

- Thestrup‐Pedersen K. Treatment principles of atopic dermatitis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology 2002;16(1):1‐9.[↩]

- Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A, Ait‐Khaled N, Anabwani G, Anderson R, et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology 1999;103(1 Pt 1):125‐38.[↩]

- Emerson RM, Williams HC, Allen BR. Severity distribution of atopic dermatitis in the community and its relationship to secondary referral. British Journal of Dermatology 1998;139(1):73‐6.[↩]

- Charman C, Williams HC. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Atopic Dermatitis. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc, 2002:21‐42.[↩]

- Beck LA, Leung DY. Allergen sensitization through the skin induces systemic allergic responses. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2000;106 Suppl 5:S258‐63.[↩]

- Fendrick AM, Baldwin JL. Allergen‐induced inflammation and the role of immunoglobulin E (IgE). American Journal of Therapeutics 2001;8(4):291‐7.[↩]

- Williams HC. Is the prevalence of atopic dermatitis increasing?. Clinical & Experimental Dermatology 1992;17(6):385‐91.[↩]

- Cookson W. Genetics and genomics of asthma and allergic diseases. Immunological Reviews 2002;190:195‐206.[↩]

- Bever HP. Early events in atopy. European Journal of Pediatrics 2002;161(10):542‐6.[↩]

- Polosa R. The interaction between particulate air pollution and allergens in enhancing allergic and airway responses. Current Allergy & Asthma Reports 2001;1(2):102‐7.[↩]

- Kalliomaki M, Isolauri E. Pandemic of atopic diseases ‐a lack of microbial exposure in early infancy?. Current Drug Targets ‐ Infectious Disorders 2002;2(3):193‐9.[↩]

- Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, Cohen BD, Sampson HA. Prevalence of IgE‐mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics 1998;101:e8.[↩]

- Archer CB. The pathophysiology and clinical features of atopic dermatitis. In: Hywel Williams editor(s). Atopic Dermatitis. The epidemiology, causes and prevention of atopic eczema. 1st Edition. Cambridge University Press, 2000:25‐40.[↩]

- Baum WF, Schneyer U, Lantzsch AM, Kloditz E. Delay of growth and development in children with bronchial asthma, atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis. Experimental & Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes 2002;110(2):53‐9.[↩]

- Ricci G, Patrizi A, Baldi E, Menna G, Tabanelli M, Masi M. Long‐term follow‐up of atopic dermatitis: retrospective analysis of related risk factors and association with concomitant allergic diseases. Journal of the American Academy Dermatology 2006;55(5):765‐71.[↩]

- Charman C, Williams HC. Measures of disease severity in atopic eczema. Archives of Dermatology 2000;136:763‐9.[↩]

- McHenry PM, Williams HC, Bingham EA. Management of atopic eczema. Joint Workshop of the British Association of Dermatologists and the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physicians of London. BMJ 1995;310(6983):843‐7.[↩]

- Lamb SR, Rademaker M. Pharmacoeconomics of drug therapy for atopic dermatitis. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2002;3(3):249‐55.[↩]

- Ernst E, Pittler MH, Stevinson C. Complementary/alternative medicine in dermatology: evidence‐assessed efficacy of two diseases and two treatments. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 2002;3(5):341‐8.[↩]

- Smethurst D. Atopic eczema. Clinical Evidence 2002;7:1467‐82.[↩]

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Eczema: Can eliminating particular foods help? 2009 Mar 18 [Updated 2017 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424896[↩][↩][↩]

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for established atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2008(1):CD005203. Published 2008 Jan 23. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005203.pub2 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6885041[↩][↩]

- Position Statement May 2010. AAAAI support of the EAACI Position Paper on IgG4* https://www.aaaai.org/aaaai/media/medialibrary/pdf%20documents/practice%20and%20parameters/eacci-igg4-2010.pdf[↩]

- Carr S, Chan E, Lavine E, Moote W. CSACI Position statement on the testing of food-specific IgG. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2012;8(1):12. Published 2012 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/1710-1492-8-12 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3443017[↩]

- Testing for IgG4 against foods is not recommended as a diagnostictool: EAACI Task Force Report* Allergy 2008: 63: 793–796 DOI: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01705.x http://www.eaaci.org/attachments/877_EAACI%20Task%20Force%20Report.pdf[↩]