Erythroplasia of Queyrat

Erythroplasia of Queyrat also called penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), in-situ squamous cell carcinoma of the penis or Bowen disease of the penis, is a rare pre-cancerous disease of the outer skin layer (epidermis) of the penis 1. The glans and prepuce of the uncircumcised uncircumcised men are most commonly involved 2. Uncircumcised males over 50 years of age are most at risk of getting erythroplasia of Queyrat or penile intraepithelial neoplasia, although it may rarely occur in younger men 3. Progression to invasive carcinoma may occur and spontaneous regression is unlikely 4. If erythroplasia of Queyrat is left untreated, 10–30% of cases develop into invasive squamous cell carcinoma (cancer) of the penis.

Some references extend use of the term erythroplasia of Queyrat to also describe squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the labia minora, vestibule, vulva, labia majora, conjunctivae, buccal mucosa, and anal mucosa 5.

Erythroplasia of Queyrat is associated with 6:

- Chronic infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), the cause of genital warts. HPV-16 is the most common type identified.

- Chronic skin disease, especially lichen sclerosus and lichen planus

- Smoking

- Immune suppression by medications or disease

- Chronic irritation by urine, friction or injury to the penile area.

Erythroplasia of Queyrat diagnosis is often delayed, because penile intraepithelial neoplasia may resemble other conditions such as balanitis (Zoon’s balanitis), candidiasis, dermatitis and psoriasis.

Lesions are single or multiple, red plaques on the glans or inner aspect of the foreskin. They may have a smooth, velvety, moist, scaly, eroded or warty surface. The following signs and symptoms may occur:

- Redness and inflammation

- Itching

- Crusting or scaling

- Pain

- Ulcers

- Bleeding

- In the late stages, discharge from the penis, difficulty pulling back foreskin or difficulty passing urine.

Literature data show treatment options for erythroplasia of Queyrat (penile intraepithelial neoplasia) include 5-fluorouracil cream, 5% imiquimod cream, cryotherapy, curettage and cautery, CO2-laser, photodynamic therapy, interferon-alpha, excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (particularly in the treatment of recurrences). Special attention should be paid to regular check-ups of sexual partners of HIV-infected patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat, in order to provide early diagnosis and treatment of cervical, vulvar and anal carcinoma 7.

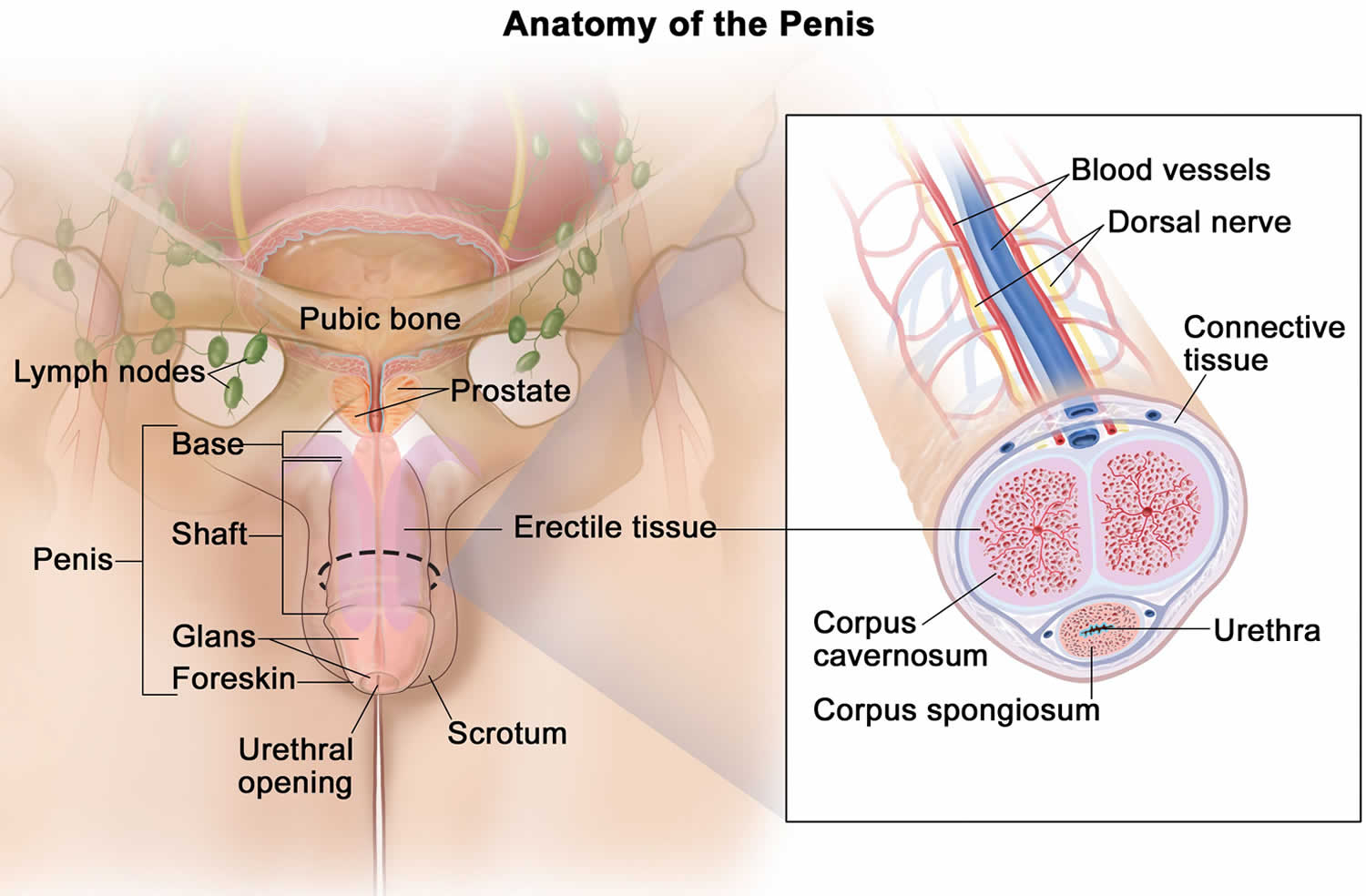

Figure 1. Penis anatomy

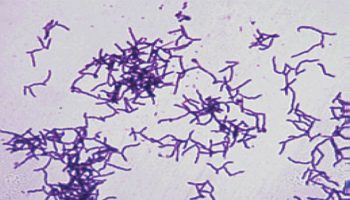

Figure 2. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (penile intraepithelial neoplasia)

Erythroplasia of Queyrat causes

The cause of erythroplasia of Queyrat (penile intraepithelial neoplasia) is not completely understood. The literature indicates that human papilloma virus (HPV) plays a significant role in its etiopathogenesis 8. About 30 different HPV types may be present in erythroplasia of Queyrat (penile intraepithelial neoplasia) lesions. They can be classified into low-oncogenic risk types (6 and 11), and potentially high risk types (16 and 18). Since 2007, literature data point to the importance of microscopic appearance of HPV infected cells in the spinous layer of the penile mucous epithelium, mostly in men under 40 years of age: koilocytosis, dyskeratosis and acanthosis 9.

The following have been proposed to contribute to the development and progression of erythroplasia of Queyrat 10, 6:

- Lack of circumcision

- Chronic irritation, inflammation, or infection: Includes urine, smegma, trauma, herpes simplex viral infection, bacteria, heat, friction, trauma

- Zoon balanitis

- Human papillomavirus infection (HPV) types 8 and 16. HPV-16 is the most common type identified. In 2010, however, Nasca et al failed to detect HPV in lesions of 11 patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat

- Immune suppression by medications or disease (including HIV infection)

- UV light

- Phimosis

- Multiple sexual partners

- Smoking

- Chronic underlying diseases (lichen sclerosis, lichen planus)

- Social/cultural habits, hygiene, religious practices

Erythroplasia of Queyrat symptoms

Patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat typically present with solitary or multiple, often times nonhealing, lesions on the glans penis and/or adjacent mucosal epithelium 11.

The clinical features of erythroplasia of Queyrat (penile intraepithelial neoplasia) include:

- Whitish areas in glans penis, coronal sulcus or inner foreskin

- Erythema (redness) and ulceration may predominate in some cases

- It may be found as an exclusive in situ lesion or associated with an invasive component

- It may be difficult to distinguish from squamous hyperplasia.

Presenting symptoms can vary and may include the following:

- Redness and inflammation

- Itching

- Crusting or scaling

- Pain

- Ulcers

- Bleeding

- In the late stages, discharge from the penis, difficulty pulling back foreskin or difficulty passing urine (dysuria).

Erythroplasia of Queyrat diagnosis

Clinical examination should be performed to assess the size, position and nature of any penile lesions. Always check underneath the foreskin, and feel for enlarged inguinal lymph nodes (number, laterality, firmness, mobility, fixation). If there are palpable lymph nodes, a CT scan is usually performed to check for impalpable pelvic lymph nodes and to assess any extra-nodal metastatic disease.

Skin biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis, as erythroplasia of Queyrat may resemble other forms of chronic balanitis. A biopsy is also essential to rule out invasive squamous cell carcinoma, which requires more aggressive treatment 10.

The following diagnostic procedures may be useful in excluding other infectious processes:

- Tzanck preparation

- Bacterial/viral/fungal culture

- Potassium hydroxide examination

- Gram stain

Early invasive disease should be evaluated for with several biopsies as needed 10. Failure to carefully evaluate any patient, especially uncircumcised patients, presenting with a subacute or chronic balanitis is a potential medicolegal pitfall. The threshold for performing skin biopsy of any lesion should be very low. In addition, a failure to diagnose erythroplasia of Queyrat expediently can easily result in disease that progresses to frank squamous cell carcinoma of the penis.

Some authors have also called for optical coherence tomography in conjunction with skin biopsy 12.

Histologic findings

Histologic findings include the following 13:

- Epidermal acanthosis, parakeratosis

- Partial- or full-thickness epidermal atypia

- Possible dyskeratosis

- Possible lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate

Erythroplasia of Queyrat treatment

It is important to maintain good genital hygiene. Erythroplasia of Queyrat (penile intraepithelial neoplasia) can be treated in several different ways. Multidisciplinary care may be necessary.

- 5-Fluorouracil cream

- 5% Imiquimod cream

- Cryotherapy

- Curettage and cautery

- Laser vaporization

- Photodynamic therapy

- Radiotherapy

- Excision

- Circumcision is recommended 10

- Interferon alpha

- Glansectomy (removal of the head of the penis). Total glansectomy and prepuce has the lowest recurrence rate at 2% for the treatment of small lesions 14.

Mohs micrographic surgery appears to be highly effective and the surgical treatment of choice in severe or recurrent cases of penile intraepithelial neoplasia.

The disease recurs in 3–10% of patients, so close follow-up is necessary to ensure a complete cure.

Partners of patients with erythroplasia of Queyrat should be screened for other forms of intraepithelial neoplasia caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) in the genital area (cervical, vulvar and anal cancer).

Many national immunization programs now include a vaccine against the causative human papillomaviruses HPV-16 and 18. Vaccination of boys and young men should be included, to reduce the risk of developing penile intraepithelial cancer in the future. Men with erythroplasia of Queyrat are sometimes treated with HPV vaccination; its efficacy in this situation is unknown.

Surgical care

Surgical treatments for erythroplasia of Queyrat include the following 15:

- Mohs micrographic surgery 16: Five-year cure rate up to 90% 11

- Surgical excision 4: Recurrence rate of 2% for total glansectomy 13; penis preserving strategies recommended for small lesions 10; may include partial glansectomy and circumcision with skin grafting 13

- Cryotherapy – cryotherapy uses liquid nitrogen to freeze and kill the cancer cells.

- Electrodesiccation and curettage

- Radiation therapy (which should be avoided)

- Carbon dioxide laser ablation 17

- Neodymium:yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser ablation 18

- Photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid: Multiple treatments may be required for clearance 19

- Photodynamic therapy with methyl-aminolevulinate: Multiple treatments may be required for clearance 20; studies have shown up to 83% of patients with clinical remission 21, but rates as low as 27% reported 22; may lead to preservation of function and good cosmesis 22; may be used in cases of recurrence or if surgery not desired 22; adverse effects include redness, burning, pain, swelling, dysuria, ulceration, blistering, and pigment changes 23.

Mohs micrographic surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery is a specialist type of surgery and one may have to be referred to a hospital to have it. Mohs micrographic surgery is sometimes used for verrucous carcinoma, a rare type of squamous cell penile cancer. Mohs micrographic surgery is a slow process because a small amount of cancer tissue is removed at a time. But the person will keep as much healthy skin as possible. During the surgery tissue is immediately examined under a microscope. If the tissue contains cancer cells, more tissue is removed and examined. The surgeon continues in this way until they have removed all the cancer. This treatment is not suitable for everyone.

Circumcision

Circumcision is the removal of the foreskin. If the cancer only affects the foreskin, this may be the only treatment that will be needed. Circumcision is also done if the patient needs radiotherapy treatment. A person can have a circumcision under a local or a general anaesthetic. After the operation the penis will be slightly swollen and bruised for about a week. There will besome stitches that will dissolve after a week to 10 days. It is important to keep the wound clean and one should wash or clean it as directed. The patient may have some pain for a few days, and need to take a mild painkiller such as acetaminophen (paracetamol). Some men worry about their sex lives after being circumcised. However there is no evidence that men who are circumcised are less sensitive or have any more difficulty getting an erection after the surgery.

Long-term monitoring

Close follow-up is recommended for patients treated medically or surgically 24. The precise follow-up regime after treatment for premalignant penile lesions is unclear. Patients should be seen 3 monthly for the first 2 years, reducing to 6 monthly to complete at least 5 years follow up, although lifelong follow up would give a better insight into the natural course of this rare condition 25.

Erythroplasia of Queyrat prognosis

The cure rate for erythroplasia of Queyrat is high if lesions are identified and treated early.

If urethral involvement is noted, treatment may be both more challenging and lead to higher recurrence rates 10.

Transformation to invasive carcinoma is possible within erythroplasia of Queyrat lesions. Graham and Helwig 3 reported 10% of erythroplasia of Queyrat cases progressing to malignant disease. Others report progression rates as high as 33% 4. Cases of erythroplasia of Queyrat metastatic to local lymph nodes have also been reported 26.

- Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia. https://cansa.org.za/files/2020/01/Fact-Sheet-on-Penile-Intraepithelial-Neoplasia-PeIN-January-2020.pdf[↩]

- Maranda EL, Nguyen AH, Lim VM, Shah VV, Jimenez JJ. Erythroplasia of Queyrat treated by laser and light modalities: a systematic review. Lasers Med Sci. 2016 Dec. 31 (9):1971-1976.[↩]

- Graham JH, Helwig EB. Erythroplasia of Queyrat. A clinicopathologic and histochemical study. Cancer. 1973 Dec. 32(6):1396-414.[↩][↩]

- Henquet CJ. Anogenital malignancies and pre-malignancies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011 Aug. 25(8):885-95.[↩][↩][↩]

- Ruocco E, Brunetti G, Del Vecchio M, Ruocco V. The practical use of cytology for diagnosis in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011 Feb. 25(2):125-9.[↩]

- Bunker CB, Neill SM. The genital, perianal and umbilical regions. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook’s textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2010. p. 71.1-102.[↩][↩]

- Kreuter A, Brockmeyer NH, Weissenborn SJ, Gambichler T, Stücker M, Altmeyer P, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia is frequent in HIV-positive men with anal dysplasia. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128:2316–24.[↩]

- Wikström A, Hedblad A, Syrjänen S. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: histopathological evaluation, HPV typing, clinical presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012;26:325-30.[↩]

- Stojanović, S., Vučković, N., & Vemic, D. (2012). Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia: Successful Treatment with Topical 5% Imiquimod Cream.[↩]

- Kutlubay Z, Engin B, Zara T, Tüzün Y. Anogenital malignancies and premalignancies: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013 Jul-Aug. 31(4):362-73.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Kirnbauer R, Lenz P, Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, and Schaffer J. Human Papillomaviruses. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. Vol 2: 1309-20.[↩][↩]

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Optical coherence tomography imaging of erythroplasia of Queyrat and treatment with imiquimod 5% cream: a case report. Dermatology. 2014. 228 (1):24-6.[↩]

- Fanning DM, Flood H. Erythroplasia of queyrat. Clin Pract. 2012 May 29. 2(3):e63.[↩][↩][↩]

- Hadway P, Corbishley CM, Watkin NA. Total glans resurfacing for premalignant lesions of the penis: initial outcome data. BJU Int. 2006 Sep;98(3):532-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06368.x[↩]

- Gerber GS. Carcinoma in situ of the penis. J Urol. 1994 Apr. 151(4):829-33.[↩]

- Jia QN, Nguyen GH, Fang K, Jin HZ, Zeng YP. Development of squamous cell carcinoma from erythroplasia of Queyrat following photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2018 Jun 1. 28 (3):405-406.[↩]

- Yamaguchi Y, Hata H, Imafuku K, Kitamura S, Shimizu H. A case of erythroplasia of Queyrat successfully treated with combination carbon dioxide laser vaporization and surgery. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Mar. 30 (3):497-8.[↩]

- Lee MR, Ryman W. Erythroplasia of Queyrat treated with topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2005 Aug. 46(3):196-8.[↩]

- Davis-Daneshfar A, Trueb RM. Bowen’s disease of the glans penis (erythroplasia of Queyrat) in plasma cell balanitis. Cutis. 2000 Jun. 65(6):395-8.[↩]

- Skroza N, LA Viola G, Pampena R, Proietti I, Bernardini N, Tolino E, et al. Erythroplasia of Queyrat treated with methyl aminolevulinate-photodynamic therapy (MAL-PDT): case report and review of the literature. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Dec 1.[↩]

- Calzavara-Pinton PG, Rossi MT, Sala R. A retrospective analysis of real-life practice of off-label photodynamic therapy using methyl aminolevulinate (MAL-PDT) in 20 Italian dermatology departments. Part 2: oncologic and infectious indications. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013 Jan. 12(1):158-65.[↩]

- Feldmeyer L, Krausz-Enderlin V, Töndury B, et al. Methylaminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in the treatment of erythroplasia of Queyrat. Dermatology. 2011. 223(1):52-6.[↩][↩][↩]

- Fai D, Romano I, Cassano N, Vena GA. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of erythroplasia of Queyrat in 23 patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011 Sep 4.[↩]

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, Dinneen M, Bunker CB. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002 Dec. 147(6):1159-65.[↩]

- Shabbir M, Minhas S, Muneer A. Diagnosis and management of premalignant penile lesions. Ther Adv Urol. 2011;3(3):151-158. doi:10.1177/1756287211412657 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3159400[↩]

- Kim B, Garcia F, Toma N, et al. A rare case of penile cancer in siu metastasizing to lymph nodes. Can Urol Assoc J. 2007. 1:404-7.[↩]