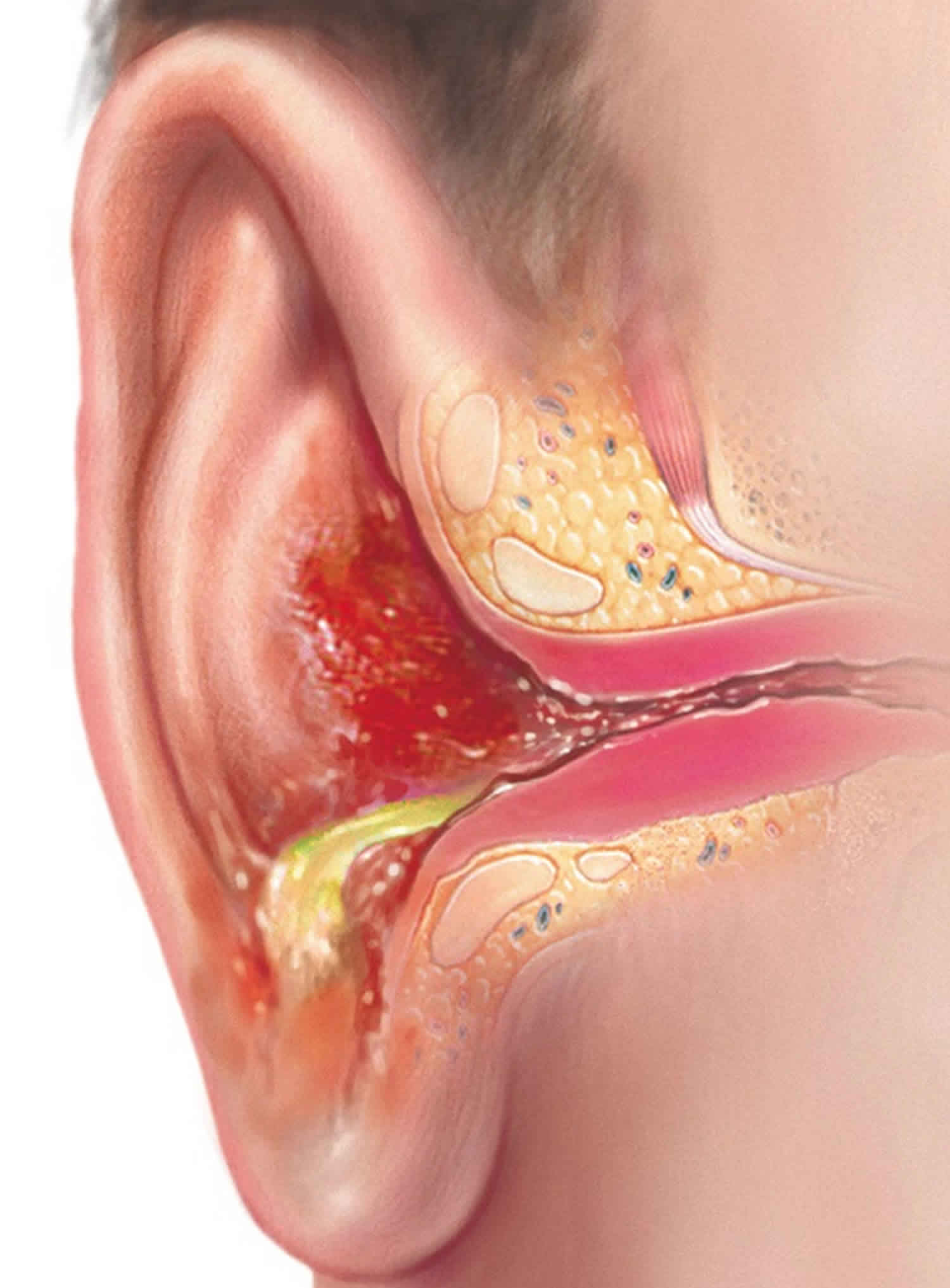

External otitis

External otitis is better known as swimmer’s ear or otitis externa, is an inflammation or infection of the outer ear canal, which runs from your eardrum to the outside of your head. External otitis is often brought on by water that remains in your ear after swimming, creating a moist environment that aids bacterial growth. Putting fingers, cotton swabs or other objects in your ears also can lead to swimmer’s ear by damaging the thin layer of skin lining your ear canal.

Otitis externa is not the same as the common childhood middle ear infection (otitis media). Otitis externa infection occurs in the outer ear canal and can cause pain and discomfort for swimmers of all ages.

The most common cause of otitis externa is bacteria invading the skin inside your ear canal. Usually you can treat swimmer’s ear with eardrops. Prompt treatment can help prevent complications and more-serious infections.

Although all age groups are affected by otitis externa, it is more common in children and can be extremely painful. Redness of the ear canal, draining fluids and discharge of pus are signs of swimmer’s ear (otitis externa). Untreated, the infection can spread to nearby tissue and bone.

Symptoms of otitis externa or swimmer’s ear usually appear within a few days of swimming and include:

- Itchiness inside the ear.

- Redness and swelling of the ear.

- Pain when the infected ear is tugged or when pressure is placed on the ear.

- Pus draining from the infected ear.

Otitis externa usually gets better quickly with treatment, and there are several things you can do to prevent swimmer’s ear.

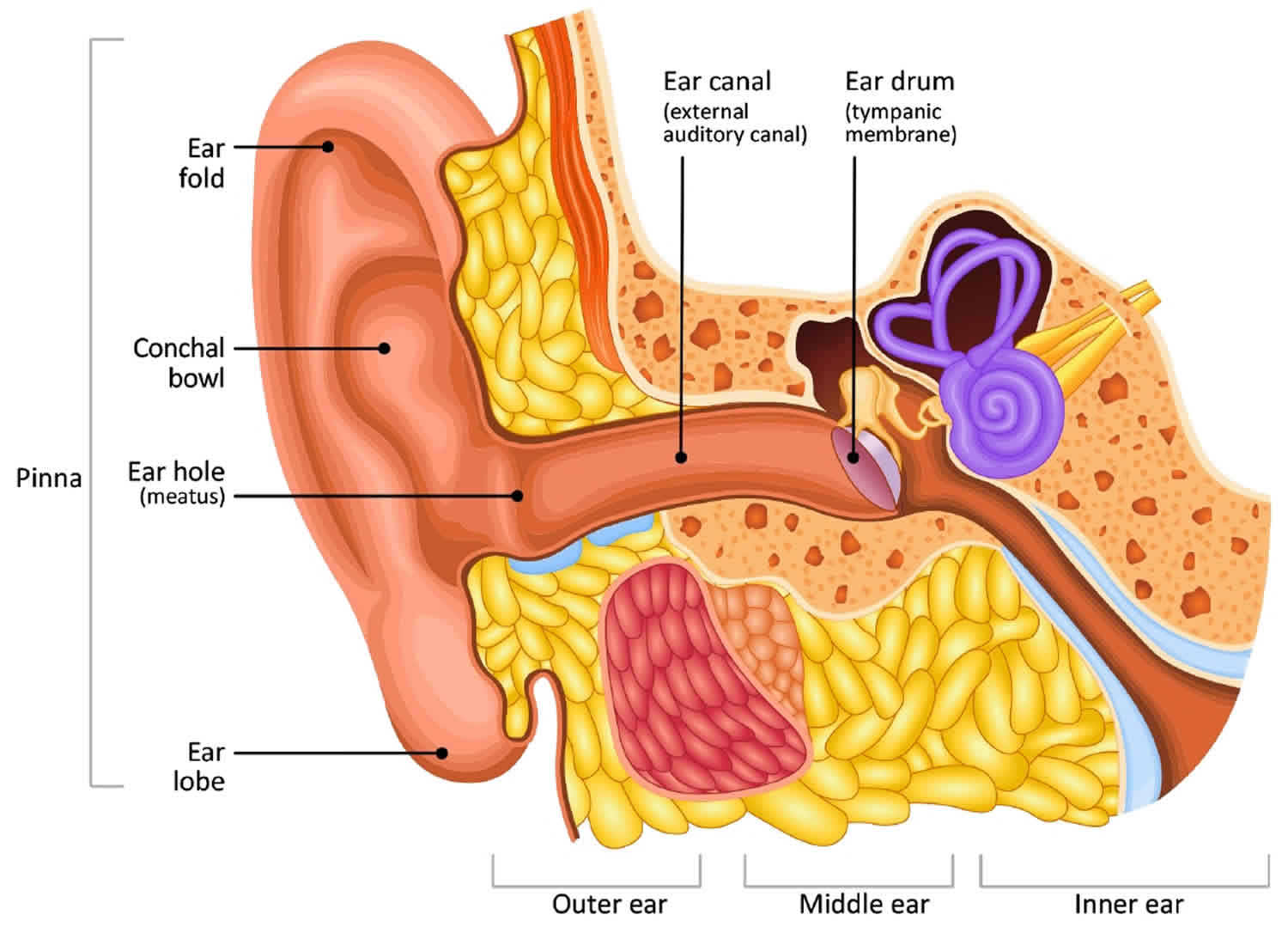

Figure 1. Ear anatomy

Contact your doctor if you have even mild signs or symptoms of swimmer’s ear.

See your doctor immediately or visit the emergency room if you have:

- Severe pain

- Fever – a very high temperature or feel hot and shivery

- Earache that does not start to get better after 3 days

- Swelling around the ear

- Fluid coming from the ear

- Hearing loss or a change in hearing

- Other symptoms, like being sick, a severe sore throat or dizziness

- Regular ear infections

- A long-term medical condition – such as diabetes or a heart, lung, kidney or neurological disease

- A weakened immune system – because of chemotherapy, for example

Otitis externa causes

Otitis externa or swimmer’s ear is an infection that’s usually caused by bacteria. It’s less common for a fungus or virus to cause swimmer’s ear.

You are more likely to get otitis externa or swimmer’s ear if you regularly get water in your ear, such as when you go swimming. A wet ear canal makes it easier to get infected. Your risk increases if the water is not clean.

Damage or irritation to the ear canal can also increase your risk. Your ear canal can be damaged or irritated from:

- scratching inside your ears

- cleaning your ear canal with a cotton bud

- wearing hearing aids

Otitis externa or swimmer’s ear can also develop if you have a fungal infection or an allergic reaction to something in your ears, such as ear plugs, medication or shampoo. You may also be more likely to get swimmer’s ear if you have skin problems such as eczema or dermatitis because the skin doesn’t act as a protective barrier.

Your ear’s natural defenses

Your outer ear canals have natural defenses that help keep them clean and prevent infection. Protective features include:

- Glands that secrete a waxy substance (cerumen). These secretions form a thin, water-repellent film on the skin inside your ear. Cerumen is also slightly acidic, which helps further discourage bacterial growth. Cerumen also collects dirt, dead skin cells and other debris and helps move these particles out of your ear, leaving the familiar earwax you find at the opening of your ear canal.

- Cartilage that partly covers the ear canal. This helps prevent foreign bodies from entering the canal.

How the infection occurs

If you have swimmer’s ear, your natural defenses have been overwhelmed. Conditions that can weaken your ear’s defenses and promote bacterial growth include:

- Excess moisture in your ear. Heavy perspiration, prolonged humid weather or water that remains in your ear after swimming can create a favorable environment for bacteria.

- Scratches or abrasions in your ear canal. Cleaning your ear with a cotton swab or hairpin, scratching inside your ear with a finger, or wearing earbuds or hearing aids can cause small breaks in the skin that allow bacteria to grow.

- Sensitivity reactions. Hair products or jewelry can cause allergies and skin conditions that promote infection.

Risk factors for otitis externa

Factors that can increase your risk of swimmer’s ear include:

- Swimming

- Getting water that has high bacteria levels in your ear

- Aggressive cleaning of the ear canal with cotton swabs or other objects

- Use of certain devices, such as earbuds or a hearing aid

- Skin allergies or irritation from jewelry, hair spray, or hair dyes.

Otitis externa prevention

Follow these tips to avoid otitis externa:

- Keep your ears dry. Dry your ears thoroughly after swimming or bathing. Dry only your outer ear, wiping it slowly and gently with a soft towel or cloth. Tip your head to the side to help water drain from your ear canal. You can dry your ears with a blow dryer if you put it on the lowest setting and hold it at least a foot (about 0.3 meters) away from the ear.

- At-home preventive treatment. If you know you don’t have a punctured eardrum, you can use homemade preventive eardrops before and after swimming. A mixture of 1 part white vinegar to 1 part rubbing alcohol can help promote drying and prevent the growth of bacteria and fungi that can cause swimmer’s ear. Pour 1 teaspoon (about 5 milliliters) of the solution into each ear and let it drain back out. Similar over-the-counter solutions might be available at your drugstore.

- Swim wisely. Watch for signs alerting swimmers to high bacterial counts, and don’t swim on those days.

- Avoid putting foreign objects in your ear. Never attempt to scratch an itch or dig out earwax with items such as a cotton swab, paper clip, or hairpin. Using these items can pack material deeper into your ear canal, irritate the thin skin inside your ear or break the skin.

- Protect your ears from irritants. Put cotton balls in your ears while applying products such as hair sprays and hair dyes.

- Use caution after an ear infection or surgery. If you’ve recently had an ear infection or ear surgery, talk to your doctor before swimming.

Otitis externa symptoms

Otitis externa or swimmer’s ear symptoms are usually mild at first, but they can worsen if your infection isn’t treated or spreads. Doctors often classify otitis externa according to mild, moderate and advanced stages of progression.

Mild signs and symptoms

- Itching in your ear canal

- Slight redness inside your ear

- Mild discomfort that’s made worse by pulling on your outer ear (pinna or auricle) or pushing on the little “bump” in front of your ear (tragus)

- Some drainage of clear, odorless fluid

Moderate progression

- More-intense itching

- Increasing pain

- More-extensive redness in your ear

- Excessive fluid drainage

- Feeling of fullness inside your ear and partial blockage of your ear canal by swelling, fluid and debris

- Decreased or muffled hearing

Advanced progression

- Severe pain that might radiate to your face, neck or side of your head

- Complete blockage of your ear canal

- Redness or swelling of your outer ear

- Swelling in the lymph nodes in your neck

- Fever

Otitis externa complications

Otitis externa usually isn’t serious if treated promptly, but complications can occur.

- Temporary hearing loss. You might have muffled hearing that usually gets better after the infection clears.

- Long-term infection (chronic otitis externa). An outer ear infection is usually considered chronic if signs and symptoms persist for more than three months. Chronic infections are more common if there are conditions that make treatment difficult, such as a rare strain of bacteria, an allergic skin reaction, an allergic reaction to antibiotic eardrops, a skin condition such as dermatitis or psoriasis, or a combination of a bacterial and a fungal infection.

- Deep tissue infection (cellulitis). Rarely, otitis externa can spread into deep layers and connective tissues of the skin.

- Bone and cartilage damage (early skull base osteomyelitis). This is a rare complication of otitis externa that occurs as the infection spreads to the cartilage of the outer ear and bones of the lower part of the skull, causing increasingly severe pain. Older adults, people with diabetes or people with weakened immune systems are at increased risk of this complication.

- More-widespread infection. If swimmer’s ear develops into advanced skull base osteomyelitis, the infection can spread and affect other parts of your body, such as the brain or nearby nerves. This rare complication can be life-threatening.

Malignant otitis externa

Malignant otitis externa also called necrotizing otitis externa, is a rare fatal aggressive infection that spreads and damages the bones and cartilage of the external ear canal, temporal bone, and the base of the skull 1. Malignant otitis externa is a dangerous complication of an outer ear infection. Malignant otitis externa is associated with serious complications with cranial nerve involvement and high mortality and morbidity rate 1. Malignant otitis externa is generally caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and it is common in elderly patients with diabetes or immunocompromised patients 2. Staphylococcus aureus; Proteus mirabilis; and some species of fungi, such as aspergillus and Candida species, have also been described to cause malignant otitis externa 3. Clinical manifestations of the disease are earache (otalgia) persisting for longer than one month, chronic otorrhea, headache, and cranial nerve involvement 4. The disease begins in the external auditory canal and then spreads to the skull base through Santorini’s fissures. Additionally, the disease spreads to the stylomastoid and jugular foramina 5. Cranial nerve involvement may occur as a result of infection progression. Facial nerve is the most common involved cranial nerve, but glossopharyngeal, vagus, accessory, or hypoglossal nerve involvements can also occur 6. Malignant otitis externa is also complicated by parotitis, mastoiditis, jugular vein thrombosis, meningitis, and death 7. The diagnosis of malignant otitis externa is made from a combination of clinical, laboratory, and radiologic findings and nuclear imaging. According to the study conducted by Cohen and Friedman 8, the major (obligatory) and minor (occasional) diagnostic criteria of malignant otitis externa are shown in Table 1.

The main treatment of malignant otitis externa is long-term antimicrobial therapy 9. Other treatment strategies are close follow-up of blood glucose levels 10, repeated local debridement of necrotic tissue, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy 11. Surgery has a limited role in the treatment of malignant otitis externa 12.

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria of malignant external otitis. All of the obligatory criteria must be present in order to establish the diagnosis. The presence of occasional criteria alone does not establish it

| Major Criteria (Obligatory) | Minor Criteria (Occasional) |

|---|---|

| Pain | Pseudomonas in culture |

| Exudate | Diabetes mellitus |

| Edema | Old age |

| Granulations | Cranial nerve involvement |

| Microabscesses (when operated) | Positive radiograph |

| Positive Technetium-99 (99Tc) bone scan of failure of local treatment after more than 1 week | Debilitating conditions |

Otitis externa diagnosis

Doctors can usually diagnose otitis externa during an office visit. If your infection is advanced or persists, you might need further evaluation.

Initial testing

Your doctor will likely diagnose otitis externa based on symptoms you report, questions he or she asks, and an office examination. You probably won’t need a lab test at your first visit. Your doctor’s initial evaluation will usually include:

- Examining your ear canal with a lighted instrument (otoscope). Your ear canal might appear red, swollen and scaly. There might be skin flakes or other debris in the ear canal.

- Looking at your eardrum (tympanic membrane) to be sure it isn’t torn or damaged. If the view of your eardrum is blocked, your doctor will clear your ear canal with a small suction device or an instrument with a tiny loop or scoop on the end.

Further testing

Depending on the initial assessment, symptom severity or the stage of your swimmer’s ear, your doctor might recommend additional evaluation, including sending a sample of fluid from your ear to test for bacteria or fungus.

In addition:

- If your eardrum is damaged or torn, your doctor will likely refer you to an ear, nose and throat specialist (ENT). The specialist will examine the condition of your middle ear to determine if that’s the primary site of infection. This examination is important because some treatments intended for an infection in the outer ear canal aren’t appropriate for treating the middle ear.

- If your infection doesn’t respond to treatment, your doctor might take a sample of discharge or debris from your ear at a later appointment and send it to a lab to identify the microorganism causing your infection.

Otitis externa treatment

The goal of treatment is to stop the infection and allow your ear canal to heal.

Cleaning

Cleaning your outer ear canal is necessary to help eardrops flow to all infected areas. Your doctor will use a suction device or ear curette to clean away discharge, clumps of earwax, flaky skin and other debris.

Medications for infection

For most cases of swimmer’s ear, your doctor will prescribe eardrops that have some combination of the following ingredients, depending on the type and seriousness of your infection:

- Acidic solution to help restore your ear’s normal antibacterial environment

- Steroid to reduce inflammation

- Antibiotic to fight bacteria

- Antifungal medication to fight infection caused by a fungus

Ask your doctor about the best method for taking your eardrops. Some ideas that may help you use eardrops include the following:

- Reduce the discomfort of cool drops by holding the bottle in your hand for a few minutes to bring the temperature of the drops closer to body temperature.

- Lie on your side with your infected ear up for a few minutes to help medication travel through the full length of your ear canal.

- If possible, have someone help you put the drops in your ear.

- To put drops in a child’s or adult’s ear, pull the ear up and back.

If your ear canal is completely blocked by swelling, inflammation or excess discharge, your doctor might insert a wick made of cotton or gauze to promote drainage and help draw medication into your ear canal.

If your infection is more advanced or doesn’t respond to treatment with eardrops, your doctor might prescribe oral antibiotics.

Medications for pain

Your doctor might recommend easing the discomfort of swimmer’s ear with over-the-counter pain relievers, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve) or acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).

If your pain is severe or your swimmer’s ear is more advanced, your doctor might prescribe a stronger medication for pain relief.

Helping your treatment work

During treatment, do the following to help keep your ears dry and avoid further irritation:

- Don’t swim or go scuba diving.

- Avoid flying.

- Don’t wear an earplug, a hearing aid or earbuds before pain or discharge has stopped.

- Avoid getting water in your ear canal when showering or bathing. Use a cotton ball coated with petroleum jelly to protect your ear during a shower or bath.

- Karaman E, Yilmaz M, Ibrahimov M, Haciyev Y, Enver O. Malignant otitis externa. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:1748–51. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31825e4d9a[↩][↩]

- Rubin J, Yu VL. Malignant external otitis: insights into pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Med. 1988;85:391–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90592-X[↩]

- Shavit SS, Soudry E, Hamzany Y, Nageris B. Malignant external otitis: Factors predicting patient outcomes. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2016.04.005[↩]

- Lee SK, Lee SA, Seon SW, Jung JH, Lee JD, Choi JY, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors in malignant external otitis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;10:228–35.[↩]

- Nadol JB., Jr Histopathology of Pseudomonas osteomyelitis of the temporal bone starting as malignant external otitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 1980;1:359–71. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(80)80016-0[↩]

- Mani N, Sudhoff H, Rajagopal S, Moffat D, Axon PR. Cranial nerve involvement in malignant external otitis: Implications for clinical outcome. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:907–10. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318039b30f[↩]

- Giamarellou H. Malignant otitis externa: The therapeutic evolution of a lethal infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30:745–51. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.6.745[↩]

- Cohen D, Friedman P. The diagnostic criteria of malignant external otitis. J Laryngol Otol. 1987;101:216–21. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100101562[↩][↩]

- Strauss M, Aber RC, Conner GH, Baum S. Malignant external otitis: Long-term (months) antimicrobial therapy. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:397–406. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198204000-00008[↩]

- Resouly A, Payne DJH, Shaw KM. Necrotizing otitis externa and diabetes control. Lancet. 1982;1:805–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91857-8[↩]

- Phillips JS, Jones SE. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjuvant treatment for malignant otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004617. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004617.pub2[↩]

- Reines JM, Schindler RA. The surgical management of recalcitrant malignant external otitis. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:369–78. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540900301[↩]