Glycosylated hemoglobin

Glycosylated hemoglobin also called glycated hemoglobin, hemoglobin A1c, HbA1c or simply A1c, is hemoglobin with glucose attached and hemoglobin A1c test identifies the average plasma glucose concentration over the past 3 months 1. Glycosylated hemoglobin develops when hemoglobin (Hb), a protein within red blood cells gives blood its bright red coloring and carries oxygen throughout your body, joins with glucose in the blood, becoming ‘glycated’ or coated with glucose from the bloodstream. The amount of glucose that is present in the blood will attach to the hemoglobin protein, and increased glucose levels will reflect on the surface of the hemoglobin protein, thereby rendering a higher HbA1c level. Glycosylated hemoglobin test shows an average of your blood sugar level over the past 90 days and represents a percentage. Glycosylated hemoglobin test can also be used to diagnose diabetes 2. By measuring glycated hemoglobin level, clinicians are able to get an overall picture of what your average blood sugar levels have been over a period of weeks/months. Since red blood cells live about an average of three months, the glycosylated hemoglobin A1c test will reflect those red blood cells that are present in the bloodstream at the time of the test; this is why the A1c serves as an average of blood sugar control. For people with diabetes this is important as the higher the HbA1c, the greater the risk of developing diabetes-related complications.

When your body processes sugar, glucose in your bloodstream naturally attaches to hemoglobin. The amount of glucose that combines with the hemoglobin protein is directly proportional to the total amount of sugar that is in your system at that time. Because red blood cells in the human body survive for 8-12 weeks before renewal, measuring glycated hemoglobin or HbA1c) can be used to reflect average blood glucose levels over that duration, providing a useful longer-term gauge of blood glucose control.

If your blood sugar levels have been high in recent weeks, your HbA1c will also be greater.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial reported that a higher mean HbA1c level was the dominant predictor of diabetic retinopathy progression. In addition to the determination of A1c levels predicting progression of retinopathy, the trial also found that a 10% decrease in HbA1c can lower the risk of retinopathy progression from 43% to 45%. Additionally, if the A1c level is decreased by 1% overall, there is a critical effect on the progression of diabetic retinopathy.

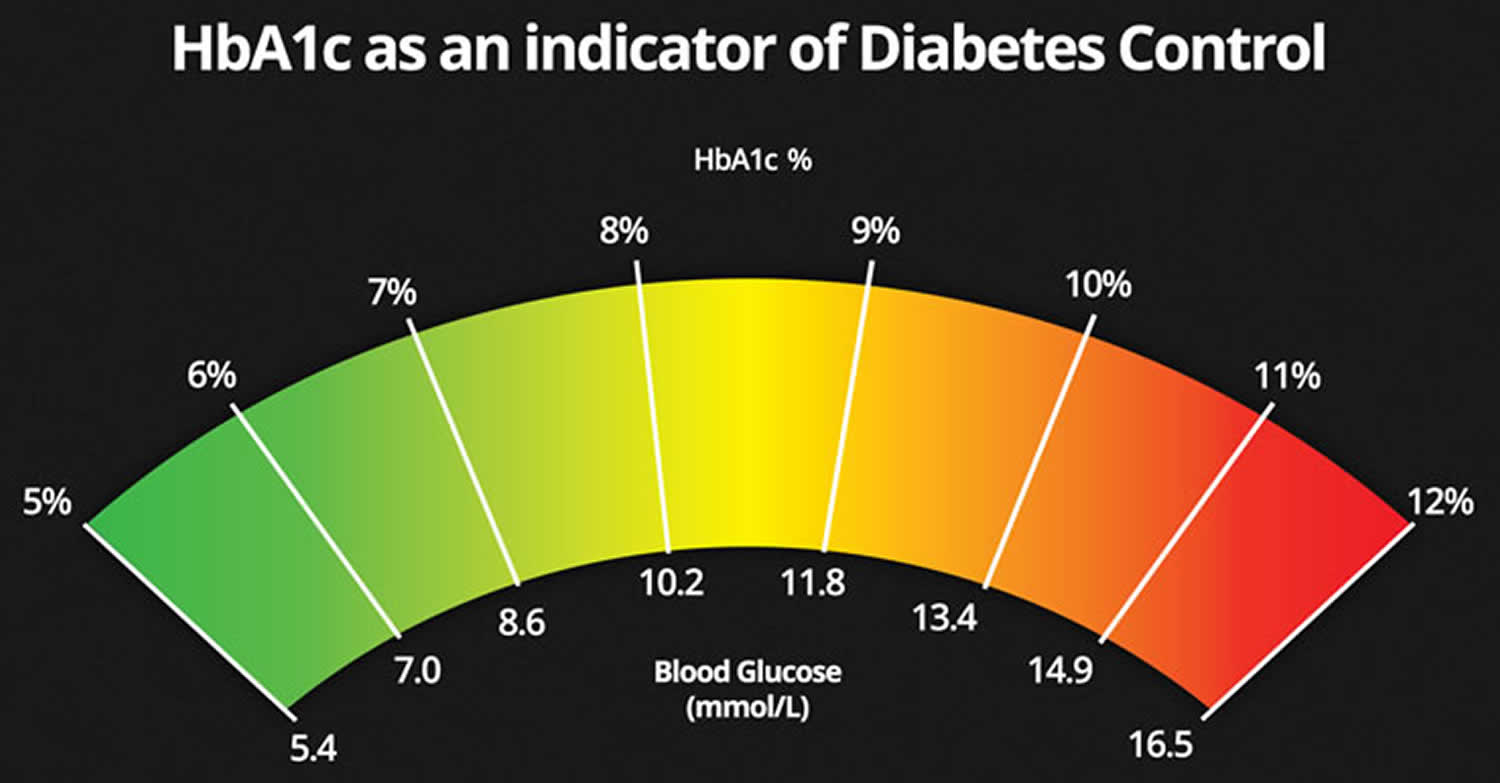

Table 1. HbA1c and average blood glucose levels

| HbA1c (%) | HbA1c (mmol/mol) | Ave. Blood Glucose (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | 119 | 18 mmol/L |

| 12 | 108 | 17 mmol/L |

| 11 | 97 | 15 mmol/L |

| 10 | 86 | 13 mmol/L |

| 9 | 75 | 12 mmol/L |

| 8 | 64 | 10 mmol/L |

| 7 | 53 | 8 mmol/L |

| 6 | 42 | 7 mmol/L |

| 5 | 31 | 5 mmol/L |

Figure 1. Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

Glycosylated hemoglobin normal range

Glycosylated hemoglobin normal range is:

- Below 39 mmol/mol (<5.7%)

Glycosylated hemoglobin in prediabetes and diabetes:

- Increased risk of developing diabetes in the future (pre-diabetes): A1c of 5.7% to 6.4% (39-46 mmol/mol)

- Diabetes: A1c level is 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) or higher

Note that the old, percentage way of reporting HbA1c values is known as the DCCT (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial) units.

The new mmols/mol values are known as the IFCC (International Federation of Clinical Chemistry) units.

Since June 2011, the way HbA1c values are reported has switched from a percentage to a measurement in mmols/mol. To make sense of the new units and compare these with old units and vice versa, use the UK Diabetes HbA1c units converter here (https://www.diabetes.co.uk/hba1c-units-converter.html).

HbA1c targets for people with diabetes

The HbA1c target for people with diabetes to aim for is:

- 48 mmol/mol (6.5%)

Note that this is a general target and people with diabetes should be given an individual target to aim towards by their health team.

An individual HbA1c should take into account your ability to achieve the target based on your day to day life and whether you are at risk of having regular or severe hypoglycemia.

Studies have shown that some people with diabetes can reduce the risk of diabetes complications by keeping A1C levels below 7 percent.

Managing blood glucose early in the course of diabetes may provide benefits for many years to come. However, an A1C level that is safe for one person may not be safe for another. For example, keeping an A1C level below 7 percent may not be safe if it leads to problems with hypoglycemia, also called low blood glucose.

Less strict blood glucose control, or an A1C between 7 and 8 percent—or even higher in some circumstances—may be appropriate in people who have:

- limited life expectancy

- long-standing diabetes and trouble reaching a lower goal

- severe hypoglycemia or inability to sense hypoglycemia (also called hypoglycemia unawareness)

- advanced diabetes complications such as chronic kidney disease, nerve problems, or cardiovascular disease

What are the benefits of lowering HbA1c?

Two large-scale studies – the UK Prospective Diabetes Study 3 and the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial 4 have demonstrated that improving HbA1c by 1% (or 11 mmol/mol) for people with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes cuts the risk of microvascular complications by 25%.

Microvascular complications include:

- Retinopathy

- Neuropathy

- Diabetic nephropathy (kidney disease)

Research has also shown that people with type 2 diabetes who reduce their HbA1c level by 1% are 5:

- 19% less likely to suffer cataracts

- 16% less likely to suffer heart failure

- 43% less likely to suffer amputation or death due to peripheral vascular disease.

Is there a home test for hemoglobin A1c?

Yes. If you have already been diagnosed with diabetes, a home test may be used to help monitor your glucose control over time. However, a home test (point-of-care test) is not recommended for screening or diagnosing the disease. There are FDA-approved tests that can be used at home.

Glycosylated hemoglobin test

The A1c test also known as the hemoglobin A1c, glycated hemoglobin or glycohemoglobin test, measures the average amount of glucose in your blood over the last 2 to 3 months by measuring the percentage of glycated hemoglobin in your blood. The A1C test result is reported as a percentage. The higher the percentage, the higher your blood glucose levels have been. A normal A1C level is below 5.7 percent.

The A1C test can be used to diagnose type 2 diabetes and prediabetes 6. Together with the fasting plasma glucose test, the HbA1c test is one of the main ways in which type 2 diabetes is diagnosed.

HbA1c tests are not the primary diagnostic test for type 1 diabetes but may sometimes be used together with other tests.

The A1C test is also the primary test used for diabetes management.

Hemoglobin is an oxygen-transporting protein found inside red blood cells. There are several types of normal hemoglobin, but the predominant form – about 95-96% – is hemoglobin A. As glucose circulates in the blood, some of it spontaneously binds to hemoglobin A.

The higher the level of glucose in the blood, the more glycated hemoglobin is formed. Once the glucose binds to the hemoglobin, it remains there for the life of the red blood cell – normally about 120 days. The predominant form of glycated hemoglobin is referred to as A1c. A1c is produced on a daily basis and slowly cleared from the blood as older red blood cells die and younger red blood cells (with non-glycated hemoglobin) take their place.

An A1c test may be used to screen for and diagnose diabetes or risk of developing diabetes. Standards of medical care in diabetes from the American Diabetes Association state that diabetes may be diagnosed based on A1c criteria or blood glucose criteria (e.g., the fasting blood glucose or the 2-hour glucose tolerance test).

A1c is also used to monitor treatment for individuals diagnosed with diabetes. It helps to evaluate how well your glucose levels have been controlled by treatment over time. For monitoring purposes, an A1c of less than 7% indicates good glucose control and a lower risk of diabetic complications for the majority of people with diabetes.

However, the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes recommend that the management of glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes be more “patient-centered.” It is recommend that people work closely with their healthcare practitioner to select a goal that reflects each person’s individual health status and that balances risks and benefits.

HbA1c in diagnosing diabetes

The hemoglobin A1c test may be used to screen for and diagnose diabetes and prediabetes in adults as follows 6:

Table 2. HbA1c can indicate people with prediabetes or diabetes

| HbA1c | mmol/mol | % |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Below 42 mmol/mol | Below 6.0% |

| Prediabetes | 42 to 47 mmol/mol | 6.0% to 6.4% |

| Diabetes | 48 mmol/mol or over | 6.5% or over |

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests the following diagnostic guidelines for diabetes:

- HbA1c below 42 mmol/mol (6.0%): Non-diabetic

- HbA1c between 42 and 47 mmol/mol (6.0–6.4%): Impaired glucose regulation or Prediabetes

- HbA1c of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) or over: Type 2 diabetes

If your HbA1c test returns a reading of 6.0–6.4%, that indicates prediabetes. Your doctor should work with you to suggest appropriate lifestyle changes that could reduce your risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

HbA1c is not used to diagnose gestational diabetes. Instead, an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is used.

A random blood glucose test will usually be used to diagnose type 1 diabetes. However, in some cases, an HbA1c test may be used to support a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.

The A1c test, should NOT be used for:

- Screening for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes

- Diagnosis of gestational diabetes in pregnant women

- Diagnosis of diabetes in children and teens

- People who have had recent severe bleeding or blood transfusions

- People with chronic kidney disease or liver disease

- People with blood disorders such as iron-deficiency anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency anemia

- Individuals with some hemoglobin variants (e.g., sickle cell disease or thalassemia)

In these cases, a fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test or fructosamine test should be used for screening or diagnosing diabetes.

Only A1c tests that have been referenced to an accepted laboratory method (National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program certified) should be used for diagnostic or screening purposes. Currently, point-of-care tests, such as those that may be used at a healthcare practitioner’s office or a patient’s bedside, are not accurate enough for use in diagnosis but can be used to monitor treatment (lifestyle and drug therapies).

HbA1c in screening for diabetes

A1c may be ordered as part of a health checkup or when someone is suspected of having diabetes because of classical signs or symptoms of increased blood glucose levels (hyperglycemia) such as:

- Increased thirst and drinking fluids

- Increased urination

- Increased appetite

- Fatigue

- Blurred vision

- Slow-healing infections

The A1c test may also be considered in adults who are overweight with the following additional risk factors:

- Physical inactivity

- First-degree relative (sibling or parent) with diabetes

- High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander)

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Abnormal lipid panel (low HDL cholesterol and/or high triglycerides)

- Women with polycystic ovary syndrome

- History of cardiovascular diseases

- Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance

The American Diabetes Association recommends to begin A1c testing at age 45 for overweight or obese people; if the result is normal, the testing should be repeated at a minimum of 3-year intervals, with consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk status, or when classical signs or symptoms of increased blood glucose levels are observed.

People who are not diagnosed with diabetes but are determined to be at increased risk for diabetes (prediabetes) should have their A1c level tested at least yearly.

HbA1c in diabetes monitoring

The A1c test is also used to monitor the glucose control of people with diabetes over time. The goal of those with diabetes is to keep their blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible. This helps to minimize the complications caused by chronically elevated glucose levels, such as progressive damage to body organs like the kidneys, eyes, cardiovascular system, and nerves. Unlike glucose results, which provide information about the glycemic status of a person strictly for the time of blood collection, the A1c test result gives a picture of the average amount of glucose in the blood over the last 2-3 months. This can help people with diabetes and their healthcare practitioners know if the measures that are being taken to control their diabetes are successful or need to be adjusted.

Depending on the type of diabetes that a person has, how well that person’s diabetes is controlled, and on the healthcare practitioner’s recommendations, the A1c test may be measured 2 to 4 times each year. The American Diabetes Association recommends A1c testing for people with diabetes at least twice a year if they are meeting treatment goals and under stable glycemic control.

A1c is frequently used to people help newly diagnosed with diabetes determine how elevated their uncontrolled blood glucose levels have been over the last 2-3 months. The A1c test is ordered several times until an optimal glucose level is achieved.

For monitoring glucose control, A1c is currently reported as a percentage and, for most people with diabetes, it is recommended that they aim to keep their hemoglobin A1c below 7%. The closer they can keep their A1c to the American Diabetes Association’s therapeutic goal of less than 7% without experiencing excessive low blood glucose (hypoglycemia), the better their diabetes is in control. As the A1c increases, so does the risk of complications.

However, if you have type 2 diabetes, you may select an A1c goal in consultation with your healthcare practitioner. The goal may depend on several factors, such as length of time since diagnosis, the presence of other diseases as well as diabetes complications (e.g., vision impairment or loss, kidney damage), risk of complications from hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, and whether or not the person has a support system and healthcare resources readily available.

For example, a person with heart disease who has lived with type 2 diabetes for many years without diabetic complications may have a higher A1c target (e.g., 7.5%-8.0%) set by their healthcare practitioner, while someone who is otherwise healthy and just diagnosed may have a lower target (e.g., 6.0%-6.5%) as long as low blood sugar is not a significant risk.

The A1c test report also may include the result expressed in SI units (mmol/mol) and an estimated Average Glucose (eAG), which is a calculated result based on the hemoglobin A1c levels. The estimated Average Glucose (eAG) reflects indirectly the glucose level over a period of 2-3 months before the A1c measurement.

The purpose of reporting estimated Average Glucose (eAG) is to help a person relate A1c results to everyday glucose monitoring levels and to laboratory glucose tests. The formula for estimated Average Glucose (eAG) converts percentage A1c to units of mg/dL or mmol/L.

The relationship between HbA1c and estimated Average Glucose (eAG) is described by the formula:

- Estimated Average Glucose (eAG) (milligrams/deciliter, mg/dL) = 28.7 X HbA1c (%) – 46.7

An example of this is an A1c of 6%. The calculation for this would be:

- 28.7 X 6 – 46.7 = 126 mg/dL

for an estimated Average Glucose (eAG) of 126 mg/dL.

What this means is that for every one percent that your A1c goes up, it is equivalent to your average glucose going up by about 29 mg/dL.

It should be noted that the estimated Average Glucose (eAG) is still an evaluation of a person’s glucose over the last couple of months. It will not match up exactly to any one daily glucose test result. The ADA has adopted this calculation and provides a calculator and information on the estimated Average Glucose (eAG) on their web site (https://professional.diabetes.org/diapro/glucose_calc). The NGSP web site also provides a calculator to convert hemoglobin A1c in SI units mmol/mol into percentage (http://www.ngsp.org/convert1.asp).

Table 3. Relationship between HbA1c and estimated Average Glucose (eAG)

| HbA1c | estimated Average Glucose (eAG) | |

| % | mg/dl | mmol/l |

| 6 | 126 | 7.0 |

| 6.5 | 140 | 7.8 |

| 7 | 154 | 8.6 |

| 7.5 | 169 | 9.4 |

| 8 | 183 | 10.1 |

| 8.5 | 197 | 10.9 |

| 9 | 212 | 11.8 |

| 9.5 | 226 | 12.6 |

| 10 | 240 | 13.4 |

How does A1C relate to estimated average glucose?

Estimated average glucose (eAG) is calculated from your A1C (see formula above). Some laboratories report eAG with A1C test results. The eAG number helps you relate your A1C to daily glucose monitoring levels. The eAG calculation converts the A1C percentage to the same units used by home glucose meters—milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL).

The eAG number will not match daily glucose readings because it’s a long-term average—rather than your blood glucose level at a single time, as is measured with a home glucose meter.

Is A1c reported the same way around the world?

For monitoring purposes, the way that the A1c is reported is in the process of changing. Traditionally, in the United States, the A1c has been reported as a percentage, and the American Diabetes Association has recommended that people with diabetes strive to keep their A1c below 7%. While this is still generally true, more than a decade of national and international efforts to improve and standardize the A1c test and its reporting led to the release of a consensus statement in 2007 and an update in 2010 by the American Diabetes Association, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC), the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, and the International Diabetes Federation. These joint statements and the completion of a study called ADAG (A1c-Derived Average Glucose) that further examined the relationship between blood glucose concentrations and A1c led to a recommendation that A1c be reported worldwide in two ways:

- As a percentage (based upon National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) derived units) and

- In SI (Système International) units (mmol/mol)

An estimated Average Glucose (eAG) based upon a formula developed from the ADAG study with either mg/dL or mmol/l as units that continue to be recognized by the American Diabetes Association and the American Association for Clinical Chemistry in the 2015 American Diabetes Association Diabetes Care Position Statement may also be reported.

What this means for people with diabetes and healthcare practitioners in the U.S. is that A1c results will be reported as a percentage but may in addition to this be reported as mmol/mol and, in some cases, also as an eAG with the same type of units (mg/dL) as are reported by home glucose monitors and laboratory results.

How does HbA1c differ from a blood glucose level?

HbA1c provides a longer-term trend, similar to an average, of how high your blood sugar levels have been over a period of time. An HbA1c reading can be taken from blood from a finger but is often taken from a blood sample that is taken from your arm. The A1c test will not reflect temporary, acute blood glucose increases or decreases, or good control that has been achieved in the last 3-4 weeks. The glucose swings of someone who has “brittle” diabetes will also not be reflected in the A1c.

Any condition that affects the quality and quantity of red blood cells (RBCs) and hemoglobin (e.g. iron deficiency, bleeding, hemolysis, etc.) will affect A1c test results. For example, if someone is iron-deficient, the A1c level may be increased or if a person receives erythropoietin therapy or has had a recent blood transfusion, the A1c may be inaccurate and may not accurately reflect glucose control for 2-3 months.

Blood glucose level is the concentration of glucose in your blood at a single point in time, i.e. the very moment of the test. This is measured using a fasting plasma glucose test, which can be carried out using blood taken from a finger or can be taken from a blood sample from the arm. However, fasting glucose tests provide an indication of your current glucose levels only, whereas the HbA1c test serves as an overall marker of what your average levels are over a period of 2-3 months.

HbA1c can be expressed as a percentage (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial unit) or as a value in mmol/mol (International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine or IFCC unit).

Note that the HbA1c value, which is measured in mmol/mol, should not be confused with a blood glucose level which is measured in mmol/l.

Why are my A1c and blood glucose different?

Beyond the difference in units used to report them, the A1c represents an average over time while your blood glucose reflects what is happening in your body now. Your blood glucose will capture the changes in your blood sugar that occur on a daily basis, the highs and the lows. Each blood glucose is a snapshot and each is different. The A1c is an indication that “in general” your glucose has been elevated over the last few months or “in general” it has been normal. It is inherently not as sensitive as a blood glucose. However, if your day-to-day glucose control is stable (good or bad), then both the A1c and blood glucose should reflect this. It is important to remember the time lag associated with the A1c. Good glucose control for the past 2-3 weeks will not significantly affect the A1c result for several more weeks.

In addition to this, it is also important to remember that glycated hemoglobin and blood glucose are two different but related things. For unknown reasons, some peoples’ A1c may not accurately reflect their average blood glucose.

Will the A1C test show short-term changes in blood glucose levels?

Large changes in your blood glucose levels over the past month will show up in your A1C test result, but the A1C test doesn’t show sudden, temporary increases or decreases in blood glucose levels. Even though A1C results represent a long-term average, blood glucose levels within the past 30 days have a greater effect on the A1C reading than those in previous months.

Can the A1C test result in a different diagnosis than the blood glucose tests?

Yes. In some people, a blood glucose test may show diabetes when an A1C test does not. The reverse can also occur—an A1C test may indicate diabetes even though a blood glucose test does not. Because of these differences in test results, health care professionals repeat tests before making a diagnosis.

People with differing test results may be in an early stage of the disease, when blood glucose levels have not risen high enough to show up on every test. In this case, health care professionals may choose to follow the person closely and repeat the test in several months.

Why do diabetes blood test results vary?

Lab test results can vary from day to day and from test to test. This can be a result of the following factors:

- Blood glucose levels move up and down

- A1C tests can be affected by changes in red blood cells or hemoglobin

- Small changes in temperature, equipment, or sample handling

Blood glucose levels move up and down

Your results can vary because of natural changes in your blood glucose level. For example, your blood glucose level moves up and down when you eat or exercise. Sickness and stress also can affect your blood glucose test results. A1C tests are less likely to be affected by short-term changes than fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) tests.

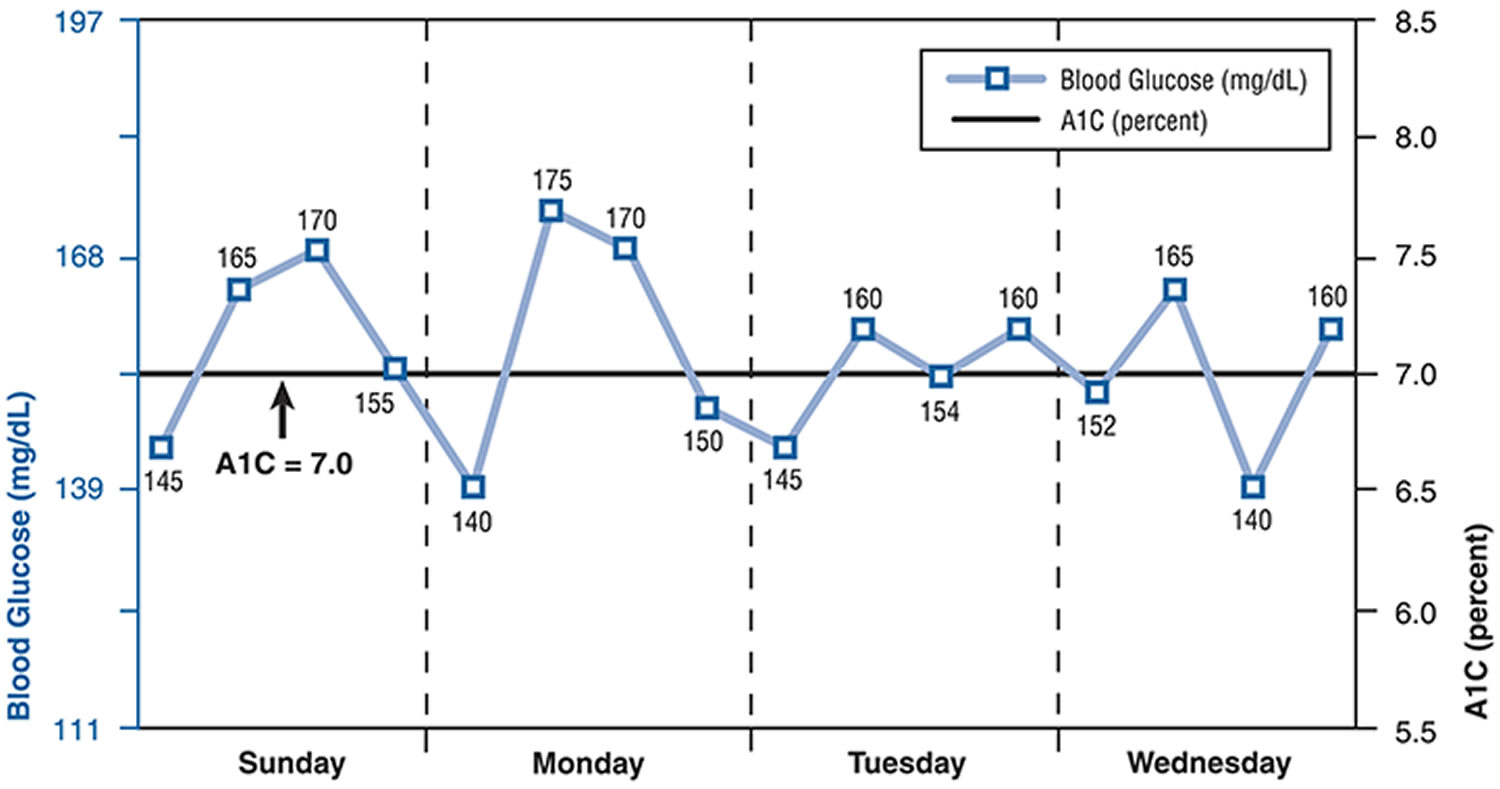

The following chart shows how multiple blood glucose measurements over 4 days compare with an A1C measurement. The straight black line shows an A1C measurement of 7.0 percent. The blue line shows an example of how blood glucose test results might look from self-monitoring four times a day over a 4-day period.

Figure 2. Blood glucose measurements compared with HbA1c measurements over 4 days

Footnote: Blood glucose (mg/dL) measurements were taken four times per day (fasting or pre-breakfast, pre-lunch, pre-dinner, and bedtime).

A1C tests can be affected by changes in red blood cells or hemoglobin

Conditions that change the life span of red blood cells, such as recent blood loss, sickle cell disease, erythropoietin treatment, hemodialysis, or transfusion, can change A1C levels.

A falsely high A1C result can occur in people who are very low in iron; for example, those with iron-deficiency anemia. Other causes of false A1C results include kidney failure or liver disease.

If you’re of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian descent or have family members with sickle cell anemia or a thalassemia, an A1C test can be unreliable for diagnosing or monitoring diabetes and prediabetes. People in these groups may have a different type of hemoglobin, known as a hemoglobin variant, which can interfere with some A1C tests. Most people with a hemoglobin variant have no symptoms and may not know that they carry this type of hemoglobin. Health care professionals may suspect interference—a falsely high or low result—when your A1C and blood glucose test results don’t match.

Not all A1C tests are unreliable for people with a hemoglobin variant. People with false results from one type of A1C test may need a different type of A1C test to measure their average blood glucose level. The National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) provides information for health care professionals about which A1C tests are appropriate to use for specific hemoglobin variants.

Small changes in temperature, equipment, or sample handling

Even when the same blood sample is repeatedly measured in the same lab, the results may vary because of small changes in temperature, equipment, or sample handling. These factors tend to affect glucose measurements—fasting and OGTT—more than the A1C test.

Health care professionals understand these variations and repeat lab tests for confirmation. Diabetes develops over time, so even with variations in test results, health care professionals can tell when overall blood glucose levels are becoming too high.

When should HbA1c levels be tested?

Everyone with diabetes mellitus should be offered an HbA1c test at least once a year.

Some people may have an HbA1c test more often. This may be more likely if you have recently had your medication changed or your health team are otherwise wishing to monitor your diabetes control more than once a year.

Although HbA1c level alone does not predict diabetes complications, good control is known to lower the risk of complications.

Can other blood glucose tests be used to diagnose type 2 diabetes and prediabetes?

Yes. Health care professionals also use the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) test and the OGTT to diagnose type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. For these blood glucose tests used to diagnose diabetes, you must fast at least 8 hours before you have your blood drawn. If you have symptoms of diabetes, your doctor may use the random plasma glucose test, which doesn’t require fasting. In some cases, health care professionals use the A1C test to help confirm the results of another blood glucose test.

How do blood glucose levels compare with HbA1c readings?

The table on the right (Table 1 above) shows how average blood sugar levels in mmol/L would be translated into HbA1c readings , and vice versa.

It is important to note that because blood glucose levels fluctuate constantly, literally on a minute by minute basis, regular blood glucose testing is required to understand how your levels are changing through the day and learning how different meals affect your glucose levels.

Is the A1C test used during pregnancy?

Health care professionals may use the A1C test early in pregnancy to see if a woman with risk factors had undiagnosed diabetes before becoming pregnant. Since the A1C test reflects your average blood glucose levels over the past 3 months, testing early in pregnancy may include values reflecting time before you were pregnant. The glucose challenge test or the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) are used to check for gestational diabetes, usually between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy. If you had gestational diabetes, you should be tested for diabetes no later than 12 weeks after your baby is born. If your blood glucose is still high, you may have type 2 diabetes. Even if your blood glucose is normal, you still have a greater chance of developing type 2 diabetes in the future and should get tested every 3 years.

How precise is the A1C test?

When repeated, the A1C test result can be slightly higher or lower than the first measurement. This means, for example, an A1C reported as 6.8 percent on one test could be reported in a range from 6.4 to 7.2 percent on a repeat test from the same blood sample.3 In the past, this range was larger but new, stricter quality-control standards mean more precise A1C test results.

Health care professionals can visit http://www.ngsp.org/index.asp to find information about the precision of the A1C test used by their lab.

- Eyth E, Naik R. Hemoglobin A1C. [Updated 2019 Oct 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549816[↩]

- Gilstrap LG, Chernew ME, Nguyen CA, Alam S, Bai B, McWilliams JM, Landon BE, Landrum MB. Association Between Clinical Practice Group Adherence to Quality Measures and Adverse Outcomes Among Adult Patients With Diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 02;2(8):e199139[↩]

- Implications of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Stud. Diabetes Care 2002 Jan; 25(suppl 1): s28-s32. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.2007.S28 https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.2007.S28[↩]

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial / Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC). https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/media/studies/edicdcct/Background_EDIC_Summary.pdf [↩]

- Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of Type 2 diabetes: prospective observational study British Medical Journal 2000; 321: 405-412.[↩]

- Gillett MJ. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(7):1327–1334.[↩][↩]