Gnathostomiasis

Gnathostomiasis is caused by several species of parasitic worms (nematodes) in the genus Gnathostoma. Gnathostomiasis is found and is most commonly diagnosed in Southeast Asia, though it has also been found elsewhere in Asia, in South and Central America, and in some areas of Africa. People become infected primarily by eating undercooked or raw freshwater fish, eels, frogs, birds, and reptiles. The most common manifestations of the infection in humans are migratory swellings under the skin and increased levels of eosinophils in the blood. Rarely, the parasite can enter other tissues such as the liver, and the eye, resulting in vision loss or blindness, and the nerves, spinal cord, or brain, resulting in nerve pain, paralysis, coma and death.

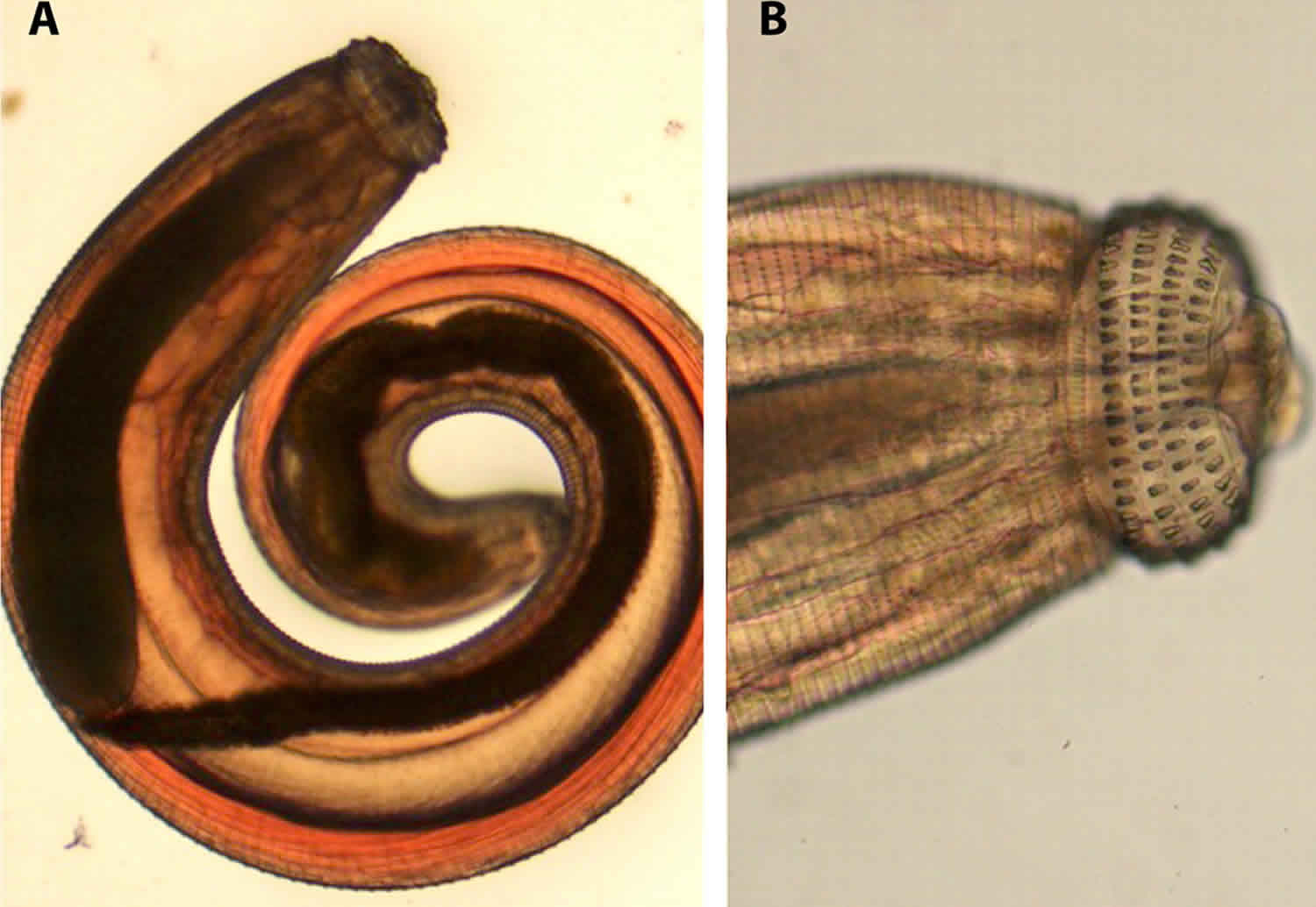

Gnathostoma spp. are spirurid nematodes characterized by the presence of a prominent cephalic bulb and body spines, and are typically associated with carnivorous mammal definitive hosts. Humans are accidental hosts; the only forms found in humans are larvae or immature adults that never reach reproductive maturity. Most human infections are caused by Gnathostoma spinigerum; other species confirmed to be zoonotic include Gnathostoma hispidum, Gnathostoma doloresi, Gnathostoma binucleatum, and Gnathostoma nipponicum. Two unconfirmed human cases of Gnathostoma malaysiae infection have been reported from Myanmar.

Gnathostoma spp. are found throughout the world, but have been reported in humans primarily in tropical and subtropical areas. Gnathostomiasis is most commonly diagnosed in Asia, particularly in Thailand, other parts of Southeast Asia, and Japan. The parasite has also been found in other areas, including South and Central America and Africa, and the diagnosis is increasingly recognized in these areas.

Gnathostomiasis causes

People become infected with Gnathostoma worm most commonly by eating undercooked and raw infected freshwater fish, though they can also become infected by eating raw or undercooked infected freshwater eels, frogs, birds, and reptiles. People might also become infected by swallowing infected water fleas or through exposure to the parasite while handling uncooked tissue from animals that are infected, though this has not been proven. Of note, it is felt that the parasite is not transmitted by eating sushi in the U.S. and Western Europe because typically the more expensive saltwater fish are used. Also there are more stringent regulations in those areas on sourcing and storage of fish that are to be eaten by humans.

Gnathostomiasis life cycle

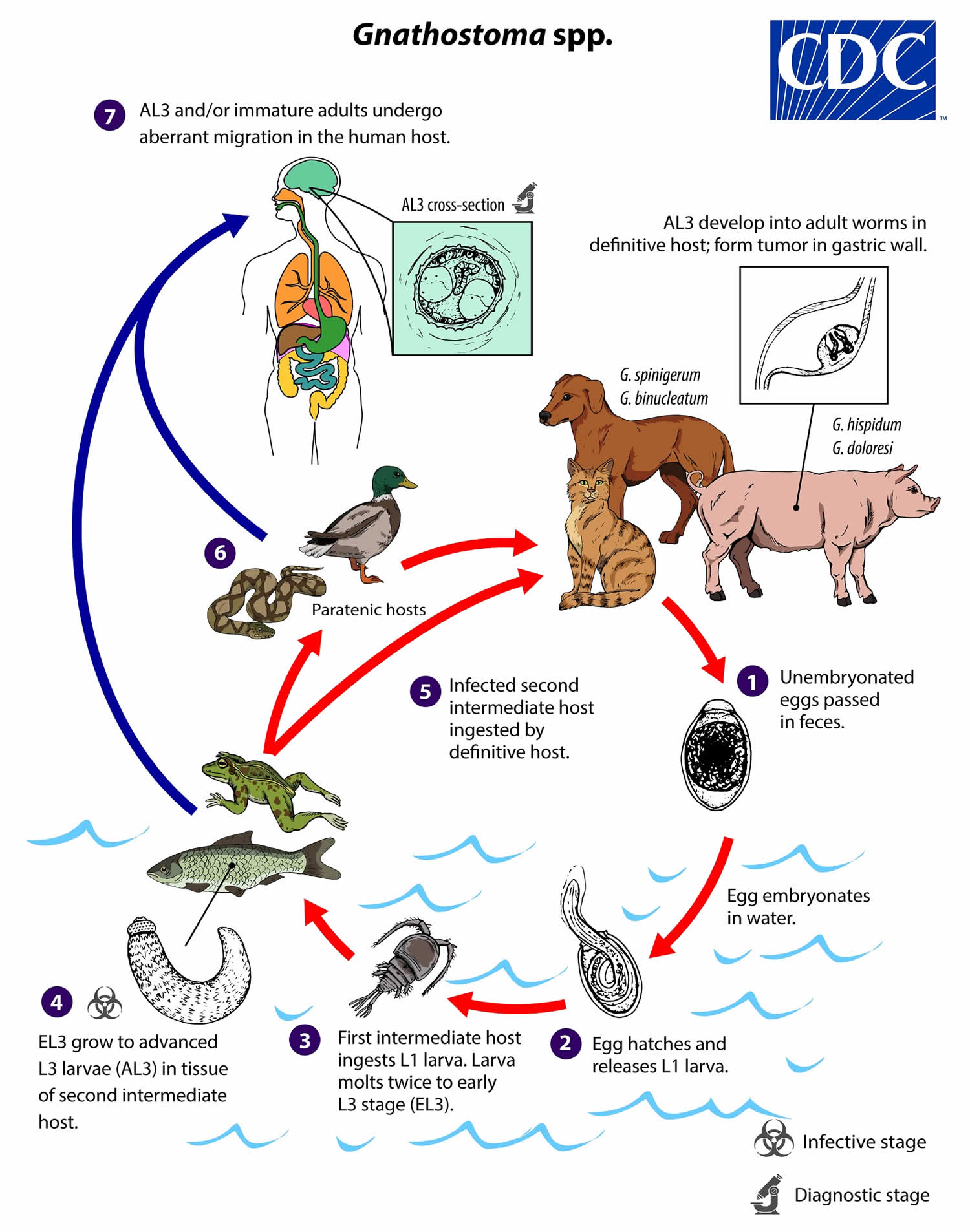

In definitive hosts, adult worms of most Gnathostoma spp reside in a tumor-like mass in the gastric wall; adult worms of some species are found in the esophagus or kidney. Adults mate and produce unembryonated eggs, which pass through a small opening in the tumor-like mass and ultimately into the feces (number #1). Eggs become embryonated in water, and eggs release sheathed first-stage larvae (L1) (number #2). Freshwater copepods, which serve as first intermediate hosts, ingest the free-swimming L1, and the larvae molt twice to become early third-stage larvae (EL3) (number #3). Following ingestion of the copepod by a suitable second intermediate host, the EL3 migrate into the tissues of the host and develop further into advanced L3 larvae (AL3) (number #4). When the second intermediate host is ingested by a definitive host, the AL3 develop into adult parasites in the gastric wall (number #5). Alternatively, the second intermediate host may be ingested by a paratenic host, in which the AL3 do not develop further but remain infective (number #6). Humans become infected by eating raw or undercooked meat of second intermediate or paratenic hosts containing AL3. In the human host, AL3 migrate in various tissues and may develop into immature adults but never achieve reproductive maturity; they may range in size from 2 mm to about 2 cm depending on the species and the extent of development (number #7). Whether humans can become infected by drinking water that contains infected copepods is not clear.

Figure 1. Gnathostomiasis life cycle

Gnathostomiasis prevention

Don’t eat undercooked or raw freshwater fish, eels, frogs, birds, and reptiles, particularly if you are in an area of the world where the parasite is commonly found. Marinating freshwater fish in lime juice, as is done in ceviche, does not kill the parasite. Avoiding contaminated freshwater in areas where the parasite is commonly found, washing your hands with soap and warm water before and after preparing food, or wearing gloves when handling raw tissue from animals that might be infected may also reduce your risk of infection, though none of these has be proven to be effective.

The FDA recommends the following for fish preparation or storage to kill parasites.

- Cooking: Cook fish adequately (to an internal temperature of at least 145° F [~63° C]).

- Freezing (Fish)

- At -4°F (-20°C) or below for 7 days (total time), or

- At -31°F (-35°C) or below until solid, and storing at -31°F (-35°C) or below for 15 hours, or

- At -31°F (-35°C) or below until solid and storing at -4°F (-20°C) or below for 24 hours.

Gnathostomiasis symptoms

The symptoms of gnathostomiasis are thought to be related to the movement of the parasite through the body. When someone eats the parasite, it moves through the wall of the stomach or intestine and liver. During this early phase, many people have no symptoms or they may experience fever, excess tiredness, lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. This phase may last for 2 or 3 weeks. Later, when the parasite moves under the skin, people may experience swellings under the skin that may be painful, red, or itchy. The swellings move around and typically are not pitting, which means that if you push on the swelling with a finger an indentation is not left behind. The swellings often begin within 3 to 4 weeks after ingestion of the parasite, but they can occur up to around 10 years after infection. The swellings typically last several weeks at a time. Rarely, Gnathostoma can enter other parts of the body, including the lungs, bladder, eyes, ears, and nervous system, including the brain. If the parasite enters the eye, it can result in vision loss or blindness. If the parasite enters a nerve or the spine, it usually results in severe nerve pain, followed by paralysis of the muscle controlled by the affected nerve. If the parasite enters the brain, it can result in headache, decreased consciousness, coma, and death. People who have a parasite that moves under the skin on the face are at higher risk for invasion of the brain and/or eye.

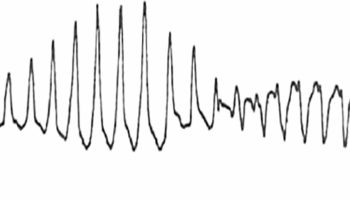

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement includes the following 1:

- Radiculomyelitis (most common), radiculomyeloencephalitis, encephalitis

- Low-grade fevers, headache, CNS depression and nonfocal neurologic symptoms

- Eosinophilic meningitis

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Excruciating radicular pain and or headache followed by paralysis, cranial nerve palsies or decreased sensorium over a few days

- Migration of focal neurologic symptoms (eg, cranial nerve palsies, paralysis of an extremity, urinary retention)

Gnathostomiasis diagnosis

The diagnosis should be considered in someone who has swellings under the skin that move around the body and an elevated level of eosinophils in the blood. The patient should be questioned about any recent history of eating undercooked or raw freshwater fish, eels, frogs, birds, or reptiles in an area where the parasite is found. Special blood tests for Gnathostoma are available, but the blood must be sent to specialty labs outside the United States.

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect IgG antibodies and Western blot are diagnostic tests 2.

- Immunoblot testing for neurologic disease has been described 3.

These tests are not widely available in the United States and many other countries.

Gnathostomiasis treatment

There are 2 antiparasitic medications that have been used successfully in patients with gnathostomiasis affecting the skin. The medications are albendazole and ivermectin. See your doctor for appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

For cutaneous symptoms of Gnathostoma infection, both albendazole and ivermectin have been shown to result in cure in several trials that were too small to firmly establish efficacy and safety of treatment.

Reported cure rates at 6 months after treatment with albendazole are >90% and after treatment with ivermectin range from 76–95.2%. Albendazole may cause outward migration of larvae. Ivermectin may cause a temporary increase of cutaneous symptoms. Two small studies in which patients were followed up for 1 year or longer found cure rates after treatment with albendazole decreased over time. Relapse is not uncommon, however, with either treatment and has been shown to occur up to 26 months after initial therapy. Monitoring for symptom recurrence is needed for all patients regardless of treatment regimen. Relapse does not necessarily require treatment with a different medication, though data on this issue also are limited.

Two different regimens of albendazole (400 mg daily for 21 days and 400 mg twice daily for 21 days) and two different regimens of ivermectin (200 mcg/kg once daily for 1 day and 200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days) have been studied. Data are insufficient to determine which regimen is the most effective, so it would probably be prudent to use the higher dose regimen of either medication until better data are available.

Whether to treat ocular and central nervous system (CNS) Gnathostoma infection remains controversial, particularly as there are no published studies of the efficacy of albendazole or ivermectin. As albendazole may cause larvae to migrate and ivermectin may cause a disease flare, there is concern that treatment with antihelminthics could worsen a patient’s neurologic status and possibly increase the risk for death or permanent neurologic deficit. There has been only one observational study of corticosteroids in patients presenting with probable Gnathostoma infection. No benefit of corticosteroids was demonstrated, possibly because it is thought that much of the damage to the CNS is caused by mechanical destruction of tissue.

At this time it is not possible to give recommendations for the treatment of CNS (central nervous system) or ocular disease other than to provide supportive care. As gnathostomiasis has been shown to cause intracranial hemorrhage, patients with neurologic disease should be carefully monitored and plans for prompt intervention should be put into place.

Albendazole

Note on treatment in pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C: Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal, or other) and there are no controlled studies in women or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Albendazole is pregnancy category C. Data on the use of albendazole in pregnant women are limited, though the available evidence suggests no difference in congenital abnormalities in the children of women who were accidentally treated with albendazole during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO allows use of albendazole in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy. However, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

It is not known whether albendazole is excreted in human milk. Albendazole should be used with caution in breastfeeding women.

Note on treatment in children

The safety of albendazole in children less than 6 years old is not certain. Studies of the use of albendazole in children as young as one year old suggest that its use is safe. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, albendazole can be used in children as young as 1 year old. Many children less than 6 years old have been treated in these campaigns with albendazole, albeit at a reduced dose.

Ivermectin

Note on treatment in pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C: Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal, or other) and there are no controlled studies in women or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Ivermectin is pregnancy category C. Data on the use of ivermectin in pregnant women are limited, though the available evidence suggests no difference in congenital abnormalities in the children of women who were accidentally treated during mass prevention campaigns with ivermectin compared with those who were not. The World Health Organization (WHO) excludes pregnant women from mass prevention campaigns that use ivermectin. However, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Note on treatment during breastfeeding

Ivermectin is excreted in low concentrations in human milk. Ivermectin should be used in breast-feeding women only when the risk to the infant is outweighed by the risk of disease progress in the mother in the absence of treatment.

Note on treatment in children

The safety of ivermectin in children who weigh less than 15kg has not been demonstrated. According to the WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, children who are at least 90 cm tall can be treated safely with ivermectin. The WHO growth standard curves show that this height is reached by 50% of boys by the time they are 28 months old and by 50% of girls by the time they are 30 months old, many children less than 3 years old been safely treated with ivermectin in mass prevention campaigns, albeit at a reduced dose.

- Katchanov J, Sawanyawisuth K, Chotmongkoi V, Nawa Y. Neurognathostomiasis, a neglected parasitosis of the central nervous system. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Jul. 17(7):1174-80.[↩]

- Bussaratid V, Dekumyoy P, Desakorn V, Jaroensuk N, Liebtawee B, Pakdee W, et al. Predictive factors for Gnathostoma seropositivity in patients visiting the Gnathostomiasis Clinic at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Thailand during 2000-2005. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010 Nov. 41(6):1316-21.[↩]

- Intapan PM, Khotsri P, Kanpittaya J, Chotmongkol V, Sawanyawisuth K, Maleewong W. Immunoblot diagnostic test for neurognathostomiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010 Oct. 83(4):927-9.[↩]