Hemispatial neglect syndrome

Hemispatial neglect also known as unilateral neglect, hemineglect or spatial neglect, is a neuropsychological syndrome occurring after damage to one hemisphere of your brain is sustained, which can result in not paying attention to the side of your body affected by the brain damage. Neglect is more than not being able to use the recovering side. Think of it as a lack of awareness of that side. This common stroke effect can reduce the possibility of independent living and increase the potential for painful injury. Hemispatial neglect is most prominent and long-lasting after damage to the right hemisphere of the human brain, particularly following a stroke. Such individuals with right-sided brain damage often fail to be aware of objects to their left, demonstrating neglect of leftward items. For example, you may not touch food on the left side of your plate or shave the left side of your face. In some cases, it can seem like there’s no left side of the body because your brain is not processing information from that side very efficiently. Spatial neglect is also associated with other cognitive symptoms affecting functional abilities and caregiver interaction, such as emotional processing dysfunction, abnormal awareness of deficits (anosognosia for hemiplegia) 1 and delirium 2. Rehabilitation involves learning to scan from side to side – finding items on a table and a wall, for instance. Hemispatial neglect also affects your ability to judge space, so therapy may involve touching things at different distances or using a full-length mirror to help process visual information. This treatment should be practiced several minutes at a time, five times per week.

Spatial neglect is defined as pathologically asymmetric spatial behavior, caused by a brain lesion and resulting in disability 3. When patients are identified as having spatial neglect, their deficits must not be fully attributable to primary sensory deficits (e.g., hemianopia) or motor disturbance (e.g., hemiparesis). Treatment for spatial neglect focuses on visuomotor, cognitive, and behavioral training, in a rehabilitation program including specific exercises. There is emerging information on biological approaches to treat this disorder, but none are yet part of standard care 4. Management of spatial neglect is also tremendously important, including alterations to the patient’s environment and caregiver counseling.

Despite the fact that speech and language, memory, and other mental abilities may be spared in brain-injured patients with spatial neglect, the prognosis for recovery of independent function in patients with spatial neglect is significantly worse than in those with seemingly more disabling deficits in these other abilities 1. Even global aphasia and right hemiparesis may not have as great an effect on the ability to become independent 5. Because spatial neglect is so disabling, it is troubling that most people with spatial neglect may not be identified, even when evaluated by stroke specialists 6.

Although patients may recover from spatial neglect as assessed on paper and pencil tests, they frequently have persistent disability, for example, reduced community mobility 7. This may be related to impaired motor-intentional Aiming in spatial neglect. Paper and pencil testing may detect mainly visual, perceptual-attention impairment (“where spatial neglect”). In contrast, assessment of actual functional performance for spatial errors captures motor-exploratory disability and predicts daily life competence 8. Thus, because motor-intentional aiming symptoms may determine how patients make adaptive movements and whether they can become independent in the home and community 1, clinicians should use functional performance assessment, and not just visual-perceptual impairment, to determine spatial neglect recovery.

Reported overall frequency of spatial neglect in the United States is estimated to be anywhere from 13–81% in people who have had a right-hemisphere stroke, although 2 studies reported an overall rate of approximately 50% 9. The frequency of spatial neglect may increase with age, but in one study did not seem to differ between men and women 10. International frequency of spatial neglect is not known. Caucasians are over-represented in clinical studies of spatial neglect, and the frequency of spatial neglect in those of low socio-economic status, and under-represented racial and cultural groups, is presently unknown and needs to be evaluated.

Hemispatial neglect causes

Causes of spatial neglect include stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumors, and aneurysm. Rarely, neurodegenerative diseases can cause neglect symptoms 11.

People with injury to either side of the brain may experience spatial neglect, but neglect occurs more commonly in persons with brain injury affecting the right cortical hemisphere, which often causes left hemiparesis 9.

Spatial neglect is not only associated with right parietal stroke. It is commonly associated with lesions of the inferior parietal lobule or temporo-parietal region, but also with lesions of the superior temporal cortex, or frontal lobe. Less common are lesions of the subcortical regions, including the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cingulate cortex 12. Subcortical damage can definitely result in disabling spatial neglect, and white matter disruption in particular is likely to contribute to development of spatial neglect 13. However, both functional changes in dynamic brain networks and structural lesions are likely to contribute to the pathological spatial bias seen in spatial neglect 14. This may explain why patients with very similar anatomic injury may present with different spatial neglect symptoms.

Mechanisms underlying hemispatial neglect

Many different cognitive deficits have been identified in patients with spatial neglect 15. These experimental findings have led to a range of hypotheses about the mechanisms underlying the condition. A large number of dissociations have been reported with some patients showing deficit A but not B, and others showing B but not A 16. Many patients show combinations of deficits, but the exact combination differs across patients 17.

One way to consider the mechanisms underlying the syndrome is to divide them into spatial or directional deficits versus non-spatial or non-directional ones.

Spatial or directional attention deficits

Many researchers have proposed that neglect may be due to a deficit in directing spatial attention, specifically in disengaging attention from ipsilesional objects and shifting it contralesionally towards the neglected side of space 18. Such a mechanism was originally implicated in patients with visual extinction following unilateral brain damage 19. Cueing attention towards the neglected side of space can help to reduce spatial biases, for example in line bisection 20.

Other investigators have emphasized a spatially lateralised bias or gradient of attention in neglect, due to disruption of the normal balance between the hemispheres in directing attention 21. Thus, after right hemisphere damage, left hemisphere mechanisms which normally orient attention rightwards may be left relatively unopposed 22. Hence the ipsilesional bias in attention observed in patients with neglect.

Some researchers have considered the spatial attention deficit in terms of the biased competition theory of attention, with ipsilesional stimuli winning in the competition for selection over contralesional ones in neglect 23. According to such accounts, more stimuli on the non-neglected, ipsilesional side would also hinder attention being directed toward contralesional items.

Evidence from a study in which the eye position of right hemisphere patients was monitored shows that their rightward bias can be completely corrected if the visual salience of stimuli to the left is increased relative to those to the right 24. Indeed, if leftward stimuli are made highly salient then these patients’ gaze can be shifted into previously neglected space. These findings would be consistent with an ipsilesional directional bias modulated by competition between leftward and rightward items in neglect patients.

Deficits in spatial frames of reference

Several studies have shown that the degree of neglect may be modulated by the position of stimuli relative to the trunk, head, eye position and even gravitational field 25. Thus different egocentric spatial reference frames appear to exert an influence on the sector of space that is neglected. Some investigators have also reported neglect for stimuli in near space or far space in different patients. All these reports have drawn inspiration from computational considerations of the transformations involved in sensorimotor control, as well as neurophysiological studies of the role of monkey posterior parietal cortex in sensorimotor transformations and motor control 26. In general, these findings support the hypothesis that there may be a deficit of spatial representation in neglect 27. However, an impaired spatial representation in neglect might also be secondary to reduced attention or exploration of contralesional space.

Spatial or directional motor deficits

Evidence also exists for a deficit in directing eye or limb movements contralesionally or to targets in contralesional space in some individuals with neglect 28. This may be a disorder of initiating movements (sometimes referred to as directional hypokinesia) or in slowness of movement execution (termed directional bradykinesia). Directional motor deficits may be modulated by locations of visual targets. One study has demonstrated slowness in initiating leftward movements to targets in left hemispace, but not those in right hemispace, in right parietal patients with neglect 28.

Spatial working memory deficits

Recent investigations have revealed that some neglect patients also have difficulty in keeping track of spatial locations across saccadic eye movements 29. Such a deficit in spatial working memory appears to exacerbate any lateralised biases in these patients. The findings suggest limitations in visual short term memory, particularly for the locations of objects 30.

Non-spatial attention deficits

A range of techniques has been used to probe non-spatial or non-directional deficits. The attentional blink paradigm has revealed a profound and long-lasting deficit in the temporal dynamics of visual processing for stimuli presented at fixation in right-hemisphere neglect patients 31. When attention is engaged on one item, such patients have difficulty in attending to subsequent items for >1 second, even when items are presented centrally, a finding reminiscent of non-spatial extinction in parietal patients 32.

Bilateral deficits (i.e. on both sides of space) have also been reported in parietal patients, with reduced capacity to encode visual stimuli presented transiently in either visual field 33.

Several groups have also reported impaired ability to sustain attention or maintain vigilance over protracted periods of time in patients with neglect, even for central auditory stimuli 34. Others have shown that there may be a bilateral constriction of the effective field of vision – the sector of space that can be attended to – which may lead to ‘local bias’ and failure to attend ‘globally’ to the periphery 35. Deficits in ‘global’ visual processing have also been reported in non-neglect patients with right temporoparietal lesions 36.

In the past, there has been a great deal of interest in object-based attention deficits in neglect 37, although a pure-object centred deficit is probably extremely rare 38.

Combinations of spatial/directional and non-spatial deficits appear to be present in different patients with neglect 17. Moreover, some of these deficits can exist in isolation of the neglect syndrome. For example, deficits in spatial working memory or sustained attention have been documented in right-hemisphere patients without neglect. However, when combined with spatially lateralised or directional biases, these deficits can serve to exacerbate the severity of neglect 39.

The combination of directional bias plus non-spatial / non-directional deficits may explain why right hemisphere lesions lead to more severe and longer lasting neglect. Both left and right hemisphere lesions may produce directional biases (e.g. extinction) but the right hemisphere may have a special role in sustained attention and spatial working memory. When deficits in these domains are comined with a directional bias, neglect may be far more severe.

Hemispatial neglect differential Diagnosis

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of spatial neglect include the following:

- Complex partial seizures

- Cortical basal ganglionic degeneration

- Multiple sclerosis

- Wallenberg (lateral medullary stroke) syndrome – Lateropulsion may produce an abnormal bed posture

- Other stroke syndromes

- Primary visual or motor systems abnormality – Such as cortical blindness or spinal cord abnormality

- Vestibular abnormality

- Posterior cortical atrophy – A neurodegenerative disorder that can be associated with spatial neglect

- Conversion disorder

- Migraine accompaniment

Hemispatial neglect symptoms

Spatial neglect is commonly observed after a stroke (cerebral infarction or hemorrhage). Because of associated abnormal self-monitoring (anosognosia), individuals usually do not report attention or perceptual problems. Thus, spatial neglect must be detected via clinical observation and testing. A complete neurologic evaluation by a thorough and knowledgeable clinician is needed to document the presence of the syndrome and even of the underlying stroke that caused it; a cursory examination in a nonaphasic patient would be unlikely to demonstrate symptoms of spatial neglect.

Spatial neglect symptoms are often first observed by caregivers or therapists, who may note personal neglect (failure to groom or clothe the contralesional side) or spatial motor Aiming neglect symptoms (may not use the contralesional limb despite adequate motor strength, or may not explore left space). Clinicians may observe the following:

- In acute care settings, patient may lie in bed or sit in a wheelchair with the head and eyes turned to the extreme ipsilesional side, usually the right. A patient may have difficulty maintaining a normal posture (may be tilted or crooked in the bed); the contralesional leg may dangle off the bed.

- When approached from the left, patients may bizarrely orient and reply to the right, away from the examiner addressing them (allesthesia or allochiria).

- People with spatial neglect may navigate their wheelchairs or veer when ambulating in a rightward-biased manner; alternately, they may collide with doorways or objects on the left.

- Spatial neglect of Where perceptual-attentional or representational types, or Aiming motor-intentional types may affect several regions of contralesional space; patients may have problems with near space, within reaching distance (peripersonal neglect), or space beyond reaching distance (extrapersonal neglect).

- Patients with spatial neglect may deny ownership of their contralateral limb, stating that it belongs to someone else (asomatognosia); they may express dislike of the paralyzed limb (misoplegia). They may report bizarre sensations or illusions such as insisting “someone is sitting on” their left arm.

- Patients may deny a neurologic problem (anosognosia), underestimate the severity or implications of their deficit, or fail to express sadness or anger about their difficulties and losses (anosodiaphoria); anosognosia particularly impairs participation in rehabilitation.

- Patients may make dangerous errors in neglecting the left side of the body; the left arm may be dragged or folded behind the back; patients who previously reliably reported angina may not report left chest pain in the presence of electrocardiographic changes consistent with ischemia; infiltrated IV sites, deep venous thrombosis affecting the left leg, or skin breakdown/infection affecting the left body may go unnoticed.

Hemispatial neglect diagnosis

In order to assess not only the type but also the severity of neglect, doctors employ a variety of tests, most of which are carried out at the patient’s bedside.

Neurologic exam

A complete neurologic examination needs to be performed. This must include a complete test of higher cortical function at the bedside. Tests of right and left hemisphere function should be performed. Specific tests for neglect often include the following:

- Line bisection test

- Letter cancellation test

- Drawing and copying

- Reading and writing

- Sensory tests – Involving double-simultaneous stimulation for extinction in the visual, auditory, somatosensory, or motor modalities

Paper-and-pencil tests, which were once the clinical standard, have been demonstrated to be less acceptable and useful than measures predictive of spatial neglect-related disability such as structured, semiquantitative observation of functional tasks 8. This kind of assessment is performed by a therapist trained to judge performance reliably, similar to administration of the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale. The therapist observes the patient to dress, eat, and transfer, among other tasks, during the examination.

If paper-and-pencil tests are used, a test that has demonstrated ability to predict spatial neglect-related disability is needed. The Behavioral Inattention Test-conventional subtest has this demonstrated predictive value 40. A disadvantage of using this test is that it takes about 15 minutes to administer 41.

Line bisection test

Line bisection tests are easy, universally available bedside tests to screen for the presence of hemispatial neglect that take only a few seconds to perform.

Detailed assessment of a patient’s ability to bisect lines is ideally accomplished using several trials with different line lengths greater than 22 cm.

Neglect is more apparent when the lines are placed in the contralesional body or head space.

The lines should be as long as possible (eg, the entire span of a page) because spatial neglect is more apparent when longer lines are used.

Cancellation task

The ability to cancel an array of lines or other stimuli may be used 42. A classic study in the Lancet revealed that omissions while completing this simple task were more predictive of disability than hemiparesis or aphasia after stroke. 43.

Double-simultaneous stimulation

Although some authors have separated extinction of contralesional stimuli to double-simultaneous stimulation from spatial neglect, this phenomenon may be categorized as a symptom of spatial neglect. Deficits in stimulus detection and stimulus awareness are observed in spatial neglect under a number of circumstances, and extinction to double-simultaneous stimulation is simply a more sensitive indicator of pathological spatial unawareness, effectively separating problems with stimulus detection due to spatial neglect from problems with stimulus detection due to unilateral sensory deficit. Testing for extinction using double-simultaneous stimulation is performed because patients may be able to detect single stimuli on the right and left hemifields but not double-simultaneous stimuli in both hemifields.

In testing for extinction using double-simultaneous stimulation, examiners may find that patients are able to detect single stimuli in the right and left hemifields, but not double-simultaneous stimuli presented in both hemifields. A contralesional stimulus may be detected when it is presented alone, but patients with spatial neglect may not perceive a contralesional stimulus when it is simultaneously presented with an ipsilesional stimulus. This may occur simultaneously with visual, tactile, or auditory modalities 3.

At the bedside, extinction to double-simultaneous stimulation can be tested by asking the patient to count fingers presented to both hemifields, making a sound such as snapping fingers near both of the patient’s ears, or touching both of the patient’s hands. Extinction cannot be tested if a patient is completely unable to detect a single stimulus in the contralesional space due to sensory deficit.

Drawing

Although time consuming, testing the ability of the patient to draw, either by having the patient draw from memory (eg, draw-a-person task) or by having the patient copy the examiner’s production (see the image below), may be one of the most sensitive means of detecting spatial neglect.

Additional tests

The patient can be observed to see if he or she has evidence of personal (body) neglect (eg, asymmetric shaving, grooming). It is interesting that some clinical practitioners, although experienced, are not attentive to pathologic asymmetry of grooming, and will insist these errors are related to hemiparesis or hemianopia. In this case, although this test does not yield a formal score, it can be useful to demonstrate body neglect by asking the patient to close his or her eyes while the examiner puts innocuous stimuli such as pieces of masking tape on various areas of the left and right body, being careful to make sure the tape is within easy reach of the good hand. This bedside test, similar to a published test for personal neglect 44, will usually convince the skeptic that the patient with personal neglect after right brain stroke can look in the left space, but does not explore the left body. Reading assessment can be useful, particularly for planning occupational and vocational rehabilitation. When reading English, patients with spatial neglect may not begin reading at the left margin; rather, they may start in the middle of the page. When asked to identify single words, they may omit left-sided letters so that “blueberry” may be read as “berry” (neglect dyslexia). Asking a patient to read numbers may be an especially sensitive way to detect neglect dyslexia; the examiner can write a few large-magnitude numbers on a piece of paper (e.g. “2,113,461”), and ask the patient to read the number (a patient with neglect dyslexia may read “661”).

Informal anosognosia testing is performed by asking the patient about his or her presentation to the hospital and the symptoms. For example, questions may include the following: “Are you weak anywhere?” It is especially effective to do this immediately after testing that reveals a deficit. Patients may be aware of some symptoms and unaware of others; a patient may be admit to have done poorly on a memory test, for example, but state that he did well on a test for spatial neglect.

Distinguish neglect and hemianopia (which may coexist) by directing the patient’s gaze into the preferred hemispace (eg, right, after a right brain injury). In many people with spatial neglect, the ability to detect visual stimuli in the contralesional retinal hemifield improves when the left and right visual hemifield are tested while they gaze into the non-neglected hemispace. In other words, a patient who is unable to see a left-sided stimulus while looking straight ahead, may be able to see a stimulus presented to approximately the same retinal area when she is looking to right of her body midline. If a stimulus can be detected in the left retinal hemifield by manipulating the body space in which the stimulus is presented, the patient is less likely to have true hemianopia 45.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests are determined based on the neurologic disorder causing the cortical or subcortical-cortical deficit (eg, stroke, tumor, aneurysm) and vary accordingly.

Check vitamin B-12 levels, thyrotropin levels, and total thyroxine levels if memory impairment accompanies spatial neglect; perform these tests for all patients, even if diagnosed with an acute neurologic syndrome. Elevated homocysteine levels should not be interpreted as idiopathic in stroke patients unless vitamin B-12 deficiency has been excluded as a possible cause.

Check rapid plasma reagent values in patients with memory disorder, especially when associated with stroke, to evaluate for potentially treatable secondary conditions. Although false-negative and false-positive results occur, false-positive results may also be clinically relevant (eg, for connective-tissue disease).

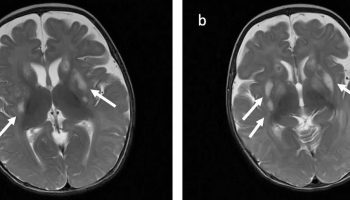

Imaging studies

Computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated even if the clinical picture is otherwise entirely consistent with a right-middle cerebral artery stroke syndrome, because subdural hematomas, brain tumors, or other mass lesions occasionally mimic a stroke. Brain imaging will help to determine whether a patient with spatial neglect after head trauma had an accident because of a stroke, as the stroke may have precipitated a fall or motor vehicle accident.

Contrast-enhanced MRI is generally nontoxic and increases the sensitivity of the technique for detecting the above diagnostic confounds. CT scanning alone is adequate to detect hemorrhage, but it is insufficiently sensitive to detect some other lesions seen with MRI. Diffusion-weighted MRI distinguishes acute ischemia from chronic infarction.

Magnetic resonance angiography, conventional angiography, or functional imaging, such as single-photon emission CT or positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, may be required for the management of stroke, brain tumor, or another primary brain disorder causing spatial neglect.

Hemispatial neglect treatment

The most important step in treatment of spatial neglect is identification of spatial neglect symptoms through an assessment. Assessment is needed that assigns a quantitative score directly related to the degree of functional disability. This means that a simple screen like the line bisection test or cancellation test is only useful to alert the team that the patient needs further assessment—these tests cannot be used to assign and follow treatment.

Treatment for spatiel neglect includes 1) management and compensation, 2) restorative therapies, and 3) caregiver, family, and patient support.

The American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) provide recommendations for spatial neglect 46.

As many as 4 out of 5 patients with spatial neglect (usually patients with milder symptoms) are not documented as having symptoms 6. It is, of course, very likely that patients who do not receive the formal diagnosis of spatial neglect do not receive the right care plan. Assessment for spatial neglect with a measure that predicts functional disability is thus a likely process marker of quality care. This assessment can be performed by an occupational therapist, physical therapist, cognitive neurologist or neuropsychologist. When patients receive this kind of assessment, it indicates that a stroke team is specialized, patient-centered, and aware of barriers affecting community re-entry.

Consultation with a skilled optometrist or ophthalmologist specialized in low vision assessment may be considered in the presence of hemianopia. A detailed bedside examination is preferred over automated methods of assessing visual-field deficits; neglect may otherwise be misinterpreted as visual field deficit. Visual assessment and vision therapy may be particularly useful when patients have both ocular disorders and spatial neglect, because these disorders may interact 47.

Consultation with a neuropsychologist can be helpful for family and caregiver counseling and for transition to long-term stages of recovery and potential community reintegration, as well as for dealing with issues of psychological adjustment by the patient, who may have intact emotional reactions but an impaired ability to communicate emotionally. A neuropsychologist should be chosen who is knowledgable about assessment and treatment of right brain disorders; this is not always part of clinical neuropsychological training.

Transitions to postacute and chronic stages of recovery can be particularly challenging for stroke survivors with spatial neglect. It is difficult for their families to anticipate the difficulties they will have, purely as a result of their stroke, in taking medications accurately, managing transfers and ambulation safely, and reintegrating into their social and community roles. Focusing planned postacute follow-up on avoiding these care transition problems may mean transitional consultation with a case manager, nurse, occupational therapist or speech-language pathologist, or psychologist, depending on which professionals are available and most skilled in particular communities.

People with mild spatial neglect symptoms living in the community, and their caregivers, may benefit greatly from neuropsychiatric consultation and couples or family therapy to adjust to chronic disability. Caregivers of people with spatial neglect are at higher risk of caregiver burden, perhaps because unawareness of deficit and safety problems increase the need for patient supervision 48.

Visual scanning training

Patients learn to do a conscious visual search of the neglect space in this intervention, usually administered by occupational therapists. Spatial cuing, and feedback to train increased amplitude of eye and head movements toward the neglected space, are essential components of this approach 49. Both the American Heart Association (AHA) and American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) groups included this intervention among recommended approaches. Limitations of this approach include failure to generalize: a patient who is able to scan leftward while reading after receiving this training may still fail to scan leftward when crossing the street. The approach also relies upon self-implementation and engagement in the therapeutic program: patients with unawareness of deficit may not respond.

Restorative therapies

Prism adaptation treatment

Both the American Heart Association and the American Occupational Therapy Association listed this treatment approach first among recommended interventions. In this treatment, patients make repeated movements with the good hand and arm while wearing binocular optical prisms. The prisms shift what they see about 11 degrees into the preferred (ipsilesional) field; unconsciously, patients increase their propensity to move into the neglected field. Patients under treatment do not need to wear the prisms at other times. The standard protocol is ten sessions over fourteen days 50. Advantages of this treatment include its effectiveness (>20 studies demonstrate it improves functional independence) 51, feasibility, and low cost. It may be particularly effective in stroke survivors with frontal brain lesions and hemiparesis 52. The major disadvantage of this treatment is that although meta-analysis suggests it results in a large magnitude of improvement in spatial neglect compared to other treatments 53, it is not yet widely implemented. When prescribing occupational therapy, physicians need to request prism adaptation treatment specifically, and ensure that the occupational therapist has been trained to administer the evidence-based protocol. Prism adaptation treatment should not be confused with prism exposure, in which prism lenses are worn by the patient during all waking hours without specific training: controlled studies supporting this approach are not available.

Limb activation

In this approach, patients receive sensory or verbal cues to make movements with the affected limbs in the neglected space during therapy sessions. By moving the weaker limb on the neglected side, spatial motor-intentional systems may be activated and, indirectly, spatial perceptual-attentional Where function as well 54. The treatment is usually administered by an occupational therapist and requires no specific equipment, although devices to facilitate left-sided movement cuing are available 55. Although different protocols have been used for this treatment, a total of 14–20 hours of treatment over 12 weeks in one or two weekly sessions is appropriate. Advantages to this treatment are its simplicity and feasibility. The disadvantage is that, like prism adaptation treatment, few occupational therapists are trained to use this approach. Therapists report that this treatment is labor-intensive, as they need to remember to implement the movement cuing, which interrupts the chain of activities in training dressing, bathing, or other therapy goals during treatment sessions.

Alternate approaches

Optikinetic stimulation, virtual reality, mental imagery, and neck vibration combined with prism adaptation are also reviewed in the American Heart Association and the American Occupational Therapy Association guidelines as supported by limited evidence. Although these approaches allow for a second- or third-line behavioral treatment plan, optikinetic stimulation, virtual reality, and neck vibration are dependent on available equipment, and few therapists are formally trained to use any of these approaches, thus their feasibility is questionable.

Medications

Although cholinergic anddopaminergic medications for spatial neglect are an exciting and developing area, this approach has not yet become standard care 4. The 2010 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Stroke Rehabilitation 56 recommends considering cholinesterase inhibitors (rivastigmine, galantamine, donepezil) for vascular cognitive impairment in the doses and frequency used for Alzheimer disease, although no medication recommendations for spatial neglect are made in this document. In the American Heart Association guidelines, recommendations for cholinesterase inhibitors for cognitive enhancement after stroke is a Class IIb recommendation (utility is unclear).

An established practice is to withhold anticholinergic medications, antidopaminergic medication (eg, for gastrointestinal indications), sedatives, and hypnotics in these patients unless absolutely necessary. These agents are likely to adversely affect the symptoms of spatial neglect and eventual functional recovery. Similarly, phenytoin is relatively contraindicated. Benzodiazepines are reported to unmask spatial neglect symptoms that previously recovered 57 and so are also contraindicated.

Patients in whom other conditions make taking the above medications necessary, must be carefully monitored and their spatial neglect symptoms periodically reevaluated.

No current clinical literature supports a benefit related to the use of modafinil in patients with spatial neglect. Although methylphenidate was helpful for spatial neglect in a small study 58, it was used in combination with behavioral prism adaptation treatment, and using this agent without prism adaptation treatment is questionable.

Safety issues

The most important issue that may have legal implications in cases of spatial neglect is driving. Patients with spatial neglect may not be allowed to drive, for their safety and the safety of the others. Unfortunately, how people with driving disability can be identified is not clear, short of an on-road standard driving evaluation by consultation through a clinical driving program. Although visual-spatial and continuous performance assessments such as the Useful Field of View 59 may be excellent predictors of driving ability in aged people, prospective psychometric development of instruments to predict driving errors in people with mild spatial neglect has not yet been performed.

Patients who have had acute spatial neglect, even if the symptoms appear to have resolved, should undergo on-road evaluation before returning to driving.

Patients should undergo an occupational/vocational rehabilitation evaluation before returning to any kind of work that involves handling machines or tools that may cause injury to self or others.

Dangerous tools, firearms, and other environmental risks should be removed from the homes of patients with spatial neglect who are homebound but are not constantly supervised. The author has observed a number of accidents in the home and workplace when patients and families were not compliant with management recommendations.

Vocational disability in spatial neglect may extend to other, non–safety-related issues. Difficulty reading left-sided material (neglect dyslexia) may lead to embarrassing errors in financial, academic, or other detail-oriented work. Spatial bias may also affect social behavior (effective audience interaction during presentations), and social-emotional changes are, of course, common after right brain stroke. A cognitive remediation program may be extremely valuable if a legal dispute arises between a stroke survivor and his or her employer about job fitness. If it is hard to locate a cognitive remediation program, one can sometimes be identified among resources primarily intended for individuals with traumatic brain injury or even developmental disabilities, and may offer referral resources to a job coach specialized in right brain neurorehabilitative challenges.

Caregiver, family, and patient support

Family members and caregivers can help survivors incrementally overcome weak-side neglect.

Here are some tips to get started:

Approach the neglected side.

Place a comfortable chair next to the bed on the neglected side. This encourages the stroke survivor to look in your direction as you speak. Hold the survivor’s hand and make contact to help increase awareness of that side. If he or she has difficulty turning their head in your direction, gently place your hand on their chin and slowly help them turn their head toward you (far enough for their eyes to meet yours). At first, you may need to do this several times a day until they can do it on their own.

Place the nightstand on the neglected side.

Placing the phone, TV remote, glass of water or other necessities on the neglected side encourages movement. One note of caution: Don’t place the control for calling the nurse on the neglected side. It should always be on the strong side where it can be found quickly.

Include the neglected hand during daily tasks.

As your stroke survivor improves, you may notice that they are still unaware of objects on one side. Saying things like “What did you forget?” or “Look to your left” aren’t very helpful. Instead, use gentle reminders such as “Here is your fork” and guide their hand. An interesting phenomenon occurs when you take someone’s hand — their head automatically turns in that direction and their eyes follow. By first saying “Let’s get your fork” and then taking their hand in yours to “search” for the fork, you’ve combined the sense of hearing with the sense of touch.

Improve awareness.

Whatever the reason for lack of awareness of one side, everyone from family members to caregivers to nurses to visiting friends and relatives can be helpful. Take every opportunity, large or small, to help survivors tune in to that side.

Every day provides simple opportunities for helping the survivor get stronger at home or in the hospital.

Hemispatial neglect prognosis

Although spatial neglect may be seen at baseline, obvious symptoms improve rapidly within the first few days 60. The potential mechanisms include reperfusion of the penumbral area and resolution of cytotoxic edema and other factors. Many patients with hemispatial neglect show early improvement. However, as many as two-thirds of patients with spatial neglect on impairment tests have persistent deficits.at 8–9 days 61. At 3 months, the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale detects neglect symptoms in 9.1% of patients 62. Because the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale does not sample functional performance, this is likely to underestimate chronic neglect prevalence.

Patients who demonstrate symptoms of spatial neglect would be expected to benefit from referral for outpatient treatment with speech therapy, occupational and physical therapy 14, neuropsychological therapy, or a combination of these referrals. Even if patients are seen as outpatients after obvious signs of spatial neglect appear to have abated, spatial bias may be present in functional tasks that cannot be detected by interacting with the patient briefly in the office environment. Whether people with spatial neglect fully recover is controversial. Although symptoms on bedside testing abate in many patients, functionally important bias, for example, limiting safety or community mobility 7, may persist.

Spatial neglect may greatly increase morbidity and the risk of acute and chronic complications of stroke (e.g., hip fracture). It is associated with a longer acute hospital stay 9, a higher risk of falls, more rehospitalizations after discharge to post-acute care, and higher rates of discharge to skilled nursing settings. Stroke patients with spatial neglect after stroke experience less functional gain after rehabilitation, despite staying longer during inpatient rehabilitation. This difference is not accounted for by their overall stroke severity, as patients matched to their level of disability on inpatient rehabilitation admission improve more rapidly. It is possible that this difference is accounted for by the effect of the neglect itself on body movements and body awareness 63. Family caregivers of patients with spatial neglect reported that their loved ones required more than 20 hours daily of care, most of which was required supervision 48. This contrasted with an average of 13.2 hours of care daily for similarly disabled stroke patients without spatial neglect. This considerable requirement to provide supervision can obviously account for increased caregiver burden caused by spatial neglect.

- Vossel S, Weiss PH, Eschenbeck P, Fink GR. Anosognosia, neglect, extinction and lesion site predict impairment of daily living after right-hemispheric stroke. Cortex. 2013 Jul-Aug. 49 (7):1782-9.[↩][↩][↩]

- Boukrina O, Barrett AM. Disruption of the ascending arousal system and cortical attention networks in post-stroke delirium and spatial neglect. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 Dec. 83:1-10.[↩]

- Ropper, AH, Samuels, MA, Klein, J.P. Neurologic disorders caused by lesions in particular parts of the cerebrum. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014. 455-485.[↩][↩]

- van der Kemp J, Dorresteijn M, Ten Brink AF, Nijboer TC, Visser-Meily JM. Pharmacological Treatment of Visuospatial Neglect: A Systematic Review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017 Apr. 26 (4):686-700.[↩][↩]

- Denes G, Semenza C, Stoppa E, Lis A. Unilateral spatial neglect and recovery from hemiplegia: a follow-up study. Brain. 1982 Sep. 105 (Pt 3):543-52.[↩]

- Chen P, McKenna C, Kutlik AM, Frisina PG. Interdisciplinary communication in inpatient rehabilitation facility: evidence of under-documentation of spatial neglect after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2013 Jun. 35 (12):1033-8.[↩][↩]

- Oh-Park M, Hung C, Chen P, Barrett AM. Severity of spatial neglect during acute inpatient rehabilitation predicts community mobility after stroke. PM R. 2014 Aug. 6 (8):716-22.[↩][↩]

- Chen P, Chen CC, Hreha K, Goedert KM, Barrett AM. Kessler Foundation Neglect Assessment Process uniquely measures spatial neglect during activities of daily living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 May. 96 (5):869-876.e1.[↩][↩]

- Chen P, Hreha K, Kong Y, Barrett AM. Impact of spatial neglect on stroke rehabilitation: evidence from the setting of an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 Aug. 96 (8):1458-66.[↩][↩][↩]

- Kortte K, Hillis AE. Recent advances in the understanding of neglect and anosognosia following right hemisphere stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009 Nov. 9 (6):459-65.[↩]

- Kas A, de Souza LC, Samri D, Bartolomeo P, Lacomblez L, Kalafat M, et al. Neural correlates of cognitive impairment in posterior cortical atrophy. Brain. 2011 May. 134 (Pt 5):1464-78.[↩]

- Karnath HO, Rorden C. The anatomy of spatial neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2012 May. 50 (6):1010-7.[↩]

- Rousseaux M, Allart E, Bernati T, Saj A. Anatomical and psychometric relationships of behavioral neglect in daily living. Neuropsychologia. 2015 Apr. 70:64-70.[↩]

- Siegel JS, Ramsey LE, Snyder AZ, Metcalf NV, Chacko RV, Weinberger K, et al. Disruptions of network connectivity predict impairment in multiple behavioral domains after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Jul 26. 113 (30):E4367-76.[↩][↩]

- Halligan PW, Fink GR, Marshall JC, Vallar G. Spatial cognition: evidence from visual neglect. Trends Cogn Sci 2003;7(3):125-133.[↩]

- Vallar G. Spatial hemineglect in humans. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 1998;2:87-97.[↩]

- Buxbaum, L.J., Ferraro, M.K., Veramonti, T., Farne, A., Whyte, J., Ladavas, E., Frassinetti, F., and Coslett, H.B. (2004). Hemispatial neglect: Subtypes, neuroanatomy, and disability. Neurology 62, 749-756.[↩][↩]

- Bartolomeo, P., and Chokron, S. (2002). Orienting of attention in left unilateral neglect. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 26, 217-234.[↩]

- Posner, M.I., Walker, J.A., Friedrich, F.J., and Rafal, R. (1984). Effects of parietal injury on covert orienting of attention. Journal of Neuroscience 4, 1863-1874.[↩]

- Riddoch, M.J., and Humphreys, G.W. (1983). The effect of cueing on unilateral neglect. Neuropsychologia 21, 589-599.[↩]

- Kinsbourne, M. (1993). Orientational bias model of unilateral neglect: Evidence from attentional gradients within hemispace. In Unilateral neglect: Clinical and Experimental Studies., I.H. Robertson and J.C. Marshall, eds. (Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum), pp. 63-86.[↩]

- Corbetta, M., Kincade, M.J., Lewis, C., Snyder, A.Z., and Sapir, A. (2005). Neural basis and recovery of spatial attentional deficits in spatial neglect. Nat Neurosci 8, 1424-1425.[↩]

- Duncan, J., Humphreys, G., and Ward, R. (1997). Competitive brain activity in visual attention. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 7, 255-261.[↩]

- Bays P.M., Singh-Curry V., Gorgoraptis N., Driver J., Husain M. (2010) Integration of Goal- and Stimulus-Related Visual Signals Revealed by Damage to Human Parietal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 5968–5978.[↩]

- Karnath, H.O., Niemeier, M., and Dichgans, J. (1998). Space exploration in neglect. Brain 121 ( Pt 12), 2357-2367.[↩]

- Andersen, R.A. (1997). Multimodal integration for the representation of space in the posterior parietal cortex. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society Lond B 1997, 1421-1428.[↩]

- Bisiach, E., and Luzzatti, C. (1978). Unilateral neglect of representational space. Cortex 14, 129-133.[↩]

- Mattingley, J.B., Husain, M., Rorden, C., Kennard, C., and Driver, J. (1998). Motor role of human inferior parietal lobe revealed in unilateral neglect patients. Nature 392, 179-182.[↩][↩]

- Mannan, S., Mort, D., Hodgson, T., Driver, J., Kennard, C., and Husain, M. (2005). Revisiting previously searched locations in visual neglect: Role of right parietal and frontal lesions in misjudging old locations as new. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 17, 340-354.[↩]

- Ferber, S., and Danckert, J. (2006). Lost in space – the fate of memory representations for non-neglected stimuli. Neuropsychologia 44, 320-325.[↩]

- Husain, M., Shapiro, K., Martin, J., and Kennard, C. (1997). Abnormal temporal dynamics of visual attention in spatial neglect patients. Nature 385, 154-156.[↩]

- Humphreys, G.W., Romani, C., Olson, A., Riddoch, M.J., and Duncan, J. (1994). Non-spatial extinction following lesions of the parietal lobes in humans. Nature 372, 357-359.[↩]

- Battelli, L., Cavanagh, P., Intriligator, J., Tramo, M.J., Henaff, M.-A., Michel, F., and Barton, J.S. (2001). Unilateral right parietal damage leads to bilateral deficit for high-level motion. Neuron 32, 985-995.[↩]

- Robertson, I.H. (2001). Do we need the “lateral” in unilateral neglect? Spatially nonselective attention deficits in unilateral neglect and their implications for rehabilitation. Neuroimage 14, S85-90.[↩]

- Russell, C., Malhotra, P., and Husain, M. (2004). Attention modulates the visual field in healthy observers and parietal patients. Neuroreport 15, 2189-2193.[↩]

- Robertson, L.C., Lamb, M.R., and Knight, R.T. (1988). Effects of lesions of temporal-parietal junction on perceptual and attentional processing in humans. Journal of Neuroscience 8, 3757-3769.[↩]

- Walker, R. (1995). Spatial and object-based neglect. Neurocase, 1, 189-207.[↩]

- Driver, J., and Pouget, A. (2000). Object-centered visual neglect, or relative egocentric neglect? J Cogn Neurosci 12, 542-545.[↩]

- Husain, M., and Rorden, C. (2003). Non-spatially lateralized mechanisms in hemispatial neglect. Nat Rev Neurosci 4, 26-36.[↩]

- Goedert KM, Chen P, Botticello A, Masmela JR, Adler U, Barrett AM. Psychometric evaluation of neglect assessment reveals motor-exploratory predictor of functional disability in acute-stage spatial neglect. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 Jan. 93 (1):137-42.[↩]

- Daffner KR, Gale SA, Barrett AM, Boeve BF, Chatterjee A, Coslett HB, et al. Improving clinical cognitive testing: report of the AAN Behavioral Neurology Section Workgroup. Neurology. 2015 Sep 8. 85 (10):910-8.[↩]

- Albert ML. A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology. 1973 Jun. 23 (6):658-64.[↩]

- Fullerton KJ, McSherry D, Stout RW. Albert’s test: a neglected test of perceptual neglect. Lancet. 1986 Feb 22. 1 (8478):430-2.[↩]

- Cocchini G, Beschin N, and Jehkonen M. The Fluff Test: A simple task to assess body representation neglect. Neuropsycholog Rehabil. 2001. 11:17-31.[↩]

- Kooistra CA, Heilman KM. Hemispatial visual inattention masquerading as hemianopia. Neurology. 1989 Aug. 39 (8):1125-7.[↩]

- Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016 Jun. 47 (6):e98-e169.[↩]

- Houston KE, Barrett AM. Patching for Diplopia Contraindicated in Patients with Brain Injury?. Optom Vis Sci. 2017 Jan. 94 (1):120-124.[↩]

- Chen P, Fyffe DC, Hreha K. Informal caregivers’ burden and stress in caring for stroke survivors with spatial neglect: an exploratory mixed-method study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2017 Jan. 24 (1):24-33.[↩][↩]

- Turton AJ, Angilley J, Chapman M, Daniel A, Longley V, Clatworthy P, et al. Visual search training in occupational therapy—an example of expert practice in community-based stroke rehabilitation. Br J Occup Ther. 2015 Sept. 78(11):674-687.[↩]

- Frassinetti F, Angeli V, Meneghello F, Avanzi S, Làdavas E. Long-lasting amelioration of visuospatial neglect by prism adaptation. Brain. 2002 Mar. 125 (Pt 3):608-23.[↩]

- Champod AS, Frank RC, Taylor K, Eskes GA. The effects of prism adaptation on daily life activities in patients with visuospatial neglect: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018 Jun. 28 (4):491-514.[↩]

- Goedert KM, Chen P, Foundas AL, Barrett AM. Frontal lesions predict response to prism adaptation treatment in spatial neglect: A randomised controlled study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018 Mar 20. 35(7):1-22.[↩]

- Yang NY, Zhou D, Chung RC, Li-Tsang CW, Fong KN. Rehabilitation Interventions for Unilateral Neglect after Stroke: A Systematic Review from 1997 through 2012. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013. 7:187.[↩]

- Riestra AR, Barrett AM. Rehabilitation of spatial neglect. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013. 110:347-55.[↩]

- Fong KN, Yang NY, Chan MK, Chan DY, Lau AF, Chan DY, et al. Combined effects of sensory cueing and limb activation on unilateral neglect in subacute left hemiplegic stroke patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2013 Jul. 27 (7):628-37.[↩]

- Management of Stroke Rehabilitation Working Group. VA/DOD Clinical practice guideline for the management of stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010. 47 (9):1-43.[↩]

- Lazar RM, Fitzsimmons BF, Marshall RS, Berman MF, Bustillo MA, Young WL, et al. Reemergence of stroke deficits with midazolam challenge. Stroke. 2002 Jan. 33 (1):283-5.[↩]

- Luauté J, Villeneuve L, Roux A, Nash S, Bar JY, Chabanat E, et al. Adding methylphenidate to prism-adaptation improves outcome in neglect patients. A randomized clinical trial. Cortex. 2018 Apr 4.[↩]

- Emerson JL, Johnson AM, Dawson JD, Uc EY, Anderson SW, Rizzo M. Predictors of driving outcomes in advancing age. Psychol Aging. 2012 Sep. 27 (3):550-9.[↩]

- Spatial Neglect. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1136474-overview#a5[↩]

- Ringman JM, Saver JL, Woolson RF, Clarke WR, Adams HP. Frequency, risk factors, anatomy, and course of unilateral neglect in an acute stroke cohort. Neurology. 2004 Aug 10. 63 (3):468-74.[↩]

- Umarova RM, Nitschke K, Kaller CP, Klöppel S, Beume L, Mader I, et al. Predictors and signatures of recovery from neglect in acute stroke. Ann Neurol. 2016 Apr. 79 (4):673-86.[↩]

- Barrett AM, Muzaffar T. Spatial cognitive rehabilitation and motor recovery after stroke. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014 Dec. 27 (6):653-8.[↩]