What is Iron

Iron is a mineral that our bodies need for many functions. In the human body, iron is present in all cells and has several vital functions — as a carrier of oxygen to the tissues from the lungs in the form of hemoglobin (Hb), as a facilitator of oxygen use and storage in the muscles as myoglobin, as a transport medium for electrons within the cells in the form of cytochromes, and as an integral part of enzyme reactions in various tissues. Too little iron can interfere with these vital functions and lead to morbidity and mortality 1, 2.

Dietary iron has two main forms: heme and nonheme 3. Plants and iron-fortified foods contain nonheme iron only, whereas meat, seafood, and poultry contain both heme and nonheme iron 4. Heme iron, which is formed when iron combines with protoporphyrin IX, contributes about 10% to 15% of total iron intakes in western populations 5.

Most of the 3 to 4 grams of elemental iron in adults is in hemoglobin 4. Much of the remaining iron is stored in the form of ferritin or hemosiderin (a degradation product of ferritin) in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow or is located in myoglobin in muscle tissue 3. Humans typically lose only small amounts of iron in urine, feces, the gastrointestinal tract, and skin. Losses are greater in menstruating women because of blood loss. Hepcidin, a circulating peptide hormone, is the key regulator of both iron absorption and the distribution of iron throughout the body, including in plasma 6.

In adults, the recommended dietary allowance of iron is 8 to 11 mg per day for men and 8 to 18 mg for women in whom higher levels are recommended during pregnancy (27 mg per day) 7. Iron is poorly absorbed and body and tissue iron stores are controlled largely by modifying rates of absorption. Adequate amounts of iron are found in most Western diets, with highest levels found in red meats and moderate levels in fish, poultry, green vegetables, cereals and grains (some of which are fortified with iron).

Your body needs the right amount of iron. If you have too little iron, you may develop iron deficiency anemia. Iron deficiency is usually due to loss of iron, predominantly as a result of blood loss in the gastrointestinal tract or from menstruation and is rarely due to deficiency in intake or an inability to absorb enough iron from foods. People at higher risk of having too little iron are young children and women who are pregnant or have periods.

Iron is also available in parenteral formulations for more rapid replacement of iron stores or for patients who do not respond to oral intake. These preparations include iron sucrose and iron dextran. Common side effects of oral replacement iron preparations include gastrointestinal upset, nausea, abdominal pain, constipation and dark stools. Rare, but potentially severe adverse reactions to iron include iron overload, hypersensitivity reactions (particularly to parenteral forms) and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Too much iron can damage your body. Taking too many iron supplements can cause iron poisoning. Some people have an inherited disease called hemochromatosis. It causes too much iron to build up in the body.

Many different measures of iron status are available, and different measures are useful at different stages of iron depletion. Measures of serum ferritin can be used to identify iron depletion at an early stage 8. A reduced rate of delivery of stored and absorbed iron to meet cellular iron requirements represents a more advanced stage of iron depletion, which is associated with reduced serum iron, reticulocyte hemoglobin, and percentage transferrin saturation and with higher total iron binding capacity, red cell zinc protoporphyrin, and serum transferrin receptor concentration. The last stage of iron deficiency, characterized by iron-deficiency anemia, occurs when blood hemoglobin concentrations, hematocrit (the proportion of red blood cells in blood by volume), mean corpuscular volume, and mean cell hemoglobin are low 9. Hemoglobin and hematocrit tests are the most commonly used measures to screen patients for iron deficiency, even though they are neither sensitive nor specific 10. Hemoglobin concentrations lower than 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in women indicate the presence of iron-deficiency anemia 10. Normal hematocrit values, which are generally three times higher than hemoglobin levels, are approximately 41% to 50% in males and 36% to 44% in females 11.

How much iron do you need ?

The amount of iron you need each day depends on your age, your sex, and whether you consume a mostly plant-based diet. Average daily recommended amounts are listed below in milligrams (mg). Vegetarians who do not eat meat, poultry, or seafood need almost twice as much iron as listed in the table because the body doesn’t absorb nonheme iron in plant foods as well as heme iron in animal foods.

| Life Stage | Recommended Amount |

|---|---|

| Birth to 6 months | 0.27 mg |

| Infants 7–12 months | 11 mg |

| Children 1–3 years | 7 mg |

| Children 4–8 years | 10 mg |

| Children 9–13 years | 8 mg |

| Teens boys 14–18 years | 11 mg |

| Teens girls 14–18 years | 15 mg |

| Adult men 19–50 years | 8 mg |

| Adult women 19–50 years | 18 mg |

| Adults 51 years and older | 8 mg |

| Pregnant teens | 27 mg |

| Pregnant women | 27 mg |

| Breastfeeding teens | 10 mg |

| Breastfeeding women | 9 mg |

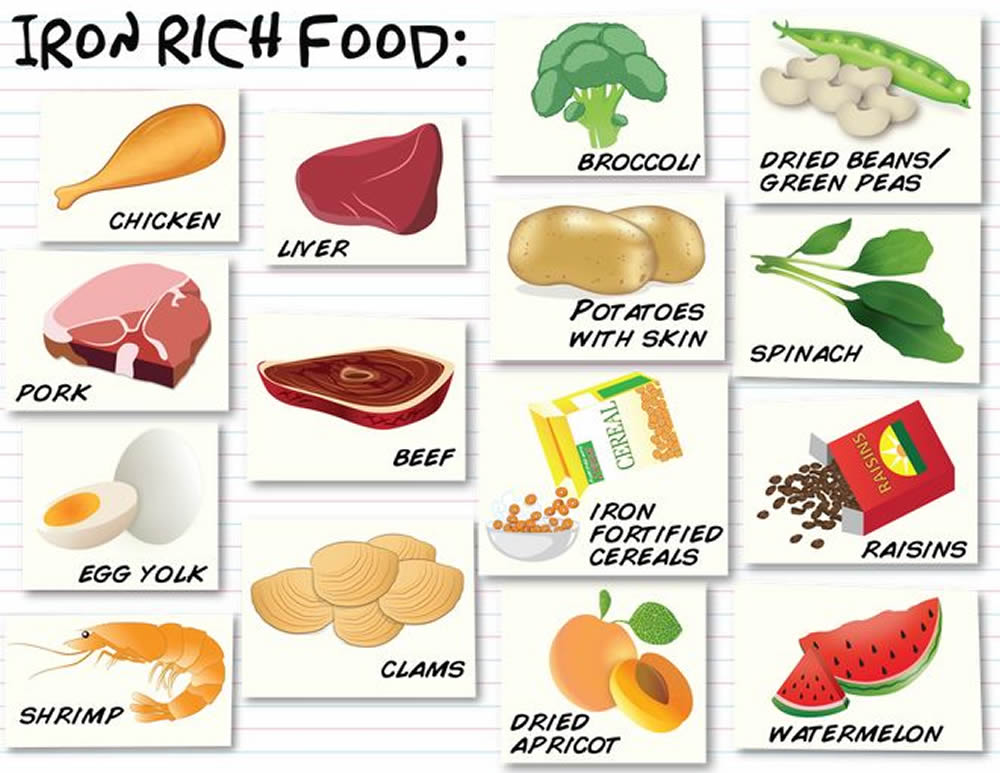

What foods provide iron ?

Iron is found naturally in many foods and is added to some fortified food products. You can get recommended amounts of iron by eating a variety of foods, including the following:

- Lean meat, seafood, and poultry.

- Iron-fortified breakfast cereals and breads.

- White beans, lentils, spinach, kidney beans, and peas.

- Nuts and some dried fruits, such as raisins.

Iron in food comes in two forms: heme iron and nonheme iron. Nonheme iron is found in plant foods and iron-fortified food products. Meat, seafood, and poultry have both heme and nonheme iron.

Heme iron has higher bioavailability than nonheme iron, and other dietary components have less effect on the bioavailability of heme than nonheme iron 5. The bioavailability of iron is approximately 14% to 18% from mixed diets that include substantial amounts of meat, seafood, and vitamin C (ascorbic acid, which enhances the bioavailability of nonheme iron) and 5% to 12% from vegetarian diets 4. In addition to ascorbic acid, meat, poultry, and seafood can enhance nonheme iron absorption, whereas phytate (present in grains and beans) and certain polyphenols in some non-animal foods (such as cereals and legumes) have the opposite effect 12. Unlike other inhibitors of iron absorption, calcium might reduce the bioavailability of both nonheme and heme iron. However, the effects of enhancers and inhibitors of iron absorption are attenuated by a typical mixed western diet, so they have little effect on most people’s iron status.

Several food sources of iron are listed in Table 2. Some plant-based foods that are good sources of iron, such as spinach, have low iron bioavailability because they contain iron-absorption inhibitors, such as polyphenols 13.

Your body absorbs iron from plant sources better when you eat it with meat, poultry, seafood, and foods that contain vitamin C, like citrus fruits, strawberries, sweet peppers, tomatoes, and broccoli.

Table 2: Selected Food Sources of Iron

| Food | Milligrams per serving | Percent DV* |

|---|---|---|

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 100% of the DV for iron, 1 serving | 18 | 100 |

| Oysters, eastern, cooked with moist heat, 3 ounces | 8 | 44 |

| White beans, canned, 1 cup | 8 | 44 |

| Chocolate, dark, 45%–69% cacao solids, 3 ounces | 7 | 39 |

| Beef liver, pan fried, 3 ounces | 5 | 28 |

| Lentils, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Spinach, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Tofu, firm, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Kidney beans, canned, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Sardines, Atlantic, canned in oil, drained solids with bone, 3 ounces | 2 | 11 |

| Chickpeas, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Tomatoes, canned, stewed, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Beef, braised bottom round, trimmed to 1/8” fat, 3 ounces | 2 | 11 |

| Potato, baked, flesh and skin, 1 medium potato | 2 | 11 |

| Cashew nuts, oil roasted, 1 ounce (18 nuts) | 2 | 11 |

| Green peas, boiled, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Chicken, roasted, meat and skin, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Rice, white, long grain, enriched, parboiled, drained, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Bread, whole wheat, 1 slice | 1 | 6 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice | 1 | 6 |

| Raisins, seedless, ¼ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Spaghetti, whole wheat, cooked, 1 cup | 1 | 6 |

| Tuna, light, canned in water, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Turkey, roasted, breast meat and skin, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Nuts, pistachio, dry roasted, 1 ounce (49 nuts) | 1 | 6 |

| Broccoli, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Egg, hard boiled, 1 large | 1 | 6 |

| Rice, brown, long or medium grain, cooked, 1 cup | 1 | 6 |

| Cheese, cheddar, 1.5 ounces | 0 | 0 |

| Cantaloupe, diced, ½ cup | 0 | 0 |

| Mushrooms, white, sliced and stir-fried, ½ cup | 0 | 0 |

| Cheese, cottage, 2% milk fat, ½ cup | 0 | 0 |

| Milk, 1 cup | 0 | 0 |

* DV = Daily Value. DVs were developed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of products within the context of a total diet. The DV for iron is 18 mg for adults and children age 4 and older. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient.

[Source 14]Are you getting enough iron ?

Most people in America get enough iron. However, certain groups of people are more likely than others to have trouble getting enough iron:

- Teen girls and women with heavy periods.

- Pregnant women and teens.

- Infants (especially if they are premature or low-birthweight).

- Frequent blood donors.

- People with cancer, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, or heart failure.

What happens if you don’t get enough iron ?

In the short term, getting too little iron does not cause obvious symptoms. The body uses its stored iron in the muscles, liver, spleen, and bone marrow. But when levels of iron stored in the body become low, iron deficiency anemia sets in. Red blood cells become smaller and contain less hemoglobin. As a result, blood carries less oxygen from the lungs throughout the body.

Symptoms of iron deficiency anemia include tiredness and lack of energy, GI upset, poor memory and concentration, and less ability to fight off germs and infections or to control body temperature. Infants and children with iron deficiency anemia might develop learning difficulties.

Iron Deficiency

Although iron deficiency is not common in the United States, iron deficiency is the most common known form of nutritional deficiency worldwide. It can occur in people who do not eat meat, poultry, or seafood; lose blood; have gastrointestinal diseases that interfere with nutrient absorption; or eat poor diets.Its prevalence is highest among young children and women of childbearing age (particularly pregnant women). In children, iron deficiency causes developmental delays and behavioral disturbances, and in pregnant women, it increases the risk for a preterm delivery and delivering a low-birthweight baby. In the past three decades, increased iron intake among infants has resulted in a decline in childhood iron-deficiency anemia in the United States. As a consequence, the use of screening tests for anemia has become a less efficient means of detecting iron deficiency in some populations. For women of childbearing age, iron deficiency has remained prevalent 2.

Iron deficiency has negative effects on work capacity and on motor and mental development in infants, children, and adolescents, and maternal iron deficiency anemia might cause low birthweight and preterm delivery 15, 16, 17. Although iron deficiency is more common in developing countries, a significant prevalence was observed in the United States during the early 1990s among certain populations, such as toddlers and females of childbearing age 18.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published recommendations to prevent iron deficiency in the United States 19. To prevent iron deficiency, vulnerable populations should be encouraged to eat iron-rich foods and breast-feed or use iron-fortified formula for infants.

The definition of iron deficiency was an abnormal value for at least two of the following three indicators: serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, and free erythrocyte protoporphyrin. Persons with iron deficiency and a low hemoglobin value were considered to have iron deficiency anemia 18.

The estimated prevalence of iron deficiency was greatest among toddlers aged 1–2 years (7%) and adolescent and adult females aged 12–49 years (9%–16%) 20. The prevalence of iron deficiency was approximately two times higher among non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American females (19%–22%) than among non-Hispanic white females (10%).

How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Diagnosed ?

Your doctor will diagnose iron-deficiency anemia based on your medical history, a physical exam, and the results from tests and procedures.

Once your doctor knows the cause and severity of the condition, he or she can create a treatment plan for you.

Mild to moderate iron-deficiency anemia may have no signs or symptoms. Thus, you may not know you have it unless your doctor discovers it from a screening test or while checking for other problems.

- Your doctor will do a physical exam to look for signs of iron-deficiency anemia. He or she may:

+ Look at your skin, gums, and nail beds to see whether they’re pale

+ Listen to your heart for rapid or irregular heartbeats

+ Listen to your lungs for rapid or uneven breathing

+ Feel your abdomen to check the size of your liver and spleen

+ Do a pelvic and rectal exam to check for internal bleeding

- Diagnostic Tests and Procedures

Many tests and procedures are used to diagnose iron-deficiency anemia. They can help confirm a diagnosis, look for a cause, and find out how severe the condition is.

+ Often, the first test used to diagnose anemia is a complete blood count (CBC). The CBC measures many parts of your blood.

This test checks your hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to the body. Hematocrit is a measure of how much space red blood cells take up in your blood. A low level of hemoglobin or hematocrit is a sign of anemia.

The normal range of these levels varies in certain racial and ethnic populations. Your doctor can explain your test results to you.

The CBC also checks the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in your blood. Abnormal results may be a sign of infection, a blood disorder, or another condition.

Finally, the CBC looks at mean corpuscular volume (MCV). MCV is a measure of the average size of your red blood cells. The results may be a clue as to the cause of your anemia. In iron-deficiency anemia, for example, red blood cells usually are smaller than normal.

- Other Blood Tests

If the CBC results confirm you have anemia, you may need other blood tests to find out what’s causing the condition, how severe it is, and the best way to treat it.

Reticulocyte count. This test measures the number of reticulocytes in your blood. Reticulocytes are young, immature red blood cells. Over time, reticulocytes become mature red blood cells that carry oxygen throughout your body.

A reticulocyte count shows whether your bone marrow is making red blood cells at the correct rate.

Peripheral smear. For this test, a sample of your blood is examined under a microscope. If you have iron-deficiency anemia, your red blood cells will look smaller and paler than normal.

- Tests to measure iron levels. These tests can show how much iron has been used from your body’s stored iron. Tests to measure iron levels include:

+ Serum iron. This test measures the amount of iron in your blood. The level of iron in your blood may be normal even if the total amount of iron in your body is low. For this reason, other iron tests also are done.

+ Serum ferritin. Ferritin is a protein that helps store iron in your body. A measure of this protein helps your doctor find out how much of your body’s stored iron has been used.

+ Transferrin level, or total iron-binding capacity. Transferrin is a protein that carries iron in your blood. Total iron-binding capacity measures how much of the transferrin in your blood isn’t carrying iron. If you have iron-deficiency anemia, you’ll have a high level of transferrin that has no iron.

Other tests. Your doctor also may recommend tests to check your hormone levels, especially your thyroid hormone. You also may have a blood test for a chemical called erythrocyte protoporphyrin. This chemical is a building block for hemoglobin.

Children also may be tested for the level of lead in their blood. Lead can make it hard for the body to produce hemoglobin.

- Tests and Procedures for Gastrointestinal Blood Loss

To check whether internal bleeding is causing your iron-deficiency anemia, your doctor may suggest a fecal occult blood test. This test looks for blood in the stools and can detect bleeding in the intestines.

If the test finds blood, you may have other tests and procedures to find the exact spot of the bleeding. These tests and procedures may look for bleeding in the stomach, upper intestines, colon, or pelvic organs.

How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Treated ?

Treatment for iron-deficiency anemia will depend on its cause and severity. Treatments may include dietary changes and supplements, medicines, and surgery.

Severe iron-deficiency anemia may require a blood transfusion, iron injections, or intravenous (IV) iron therapy. Treatment may need to be done in a hospital.

The goals of treating iron-deficiency anemia are to treat its underlying cause and restore normal levels of red blood cells, hemoglobin, and iron.

- Dietary Changes and Supplements

Iron

You may need iron supplements to build up your iron levels as quickly as possible. Iron supplements can correct low iron levels within months. Supplements come in pill form or in drops for children.

Large amounts of iron can be harmful, so take iron supplements only as your doctor prescribes. Keep iron supplements out of reach from children. This will prevent them from taking an overdose of iron.

Iron supplements can cause side effects, such as dark stools, stomach irritation, and heartburn. Iron also can cause constipation, so your doctor may suggest that you use a stool softener.

Your doctor may advise you to eat more foods that are rich in iron. The best source of iron is red meat, especially beef and liver. Chicken, turkey, pork, fish, and shellfish also are good sources of iron.

The body tends to absorb iron from meat better than iron from nonmeat foods. However, some nonmeat foods also can help you raise your iron levels. Examples of nonmeat foods that are good sources of iron include:

- Iron-fortified breads and cereals

+ Peas; lentils; white, red, and baked beans; soybeans; and chickpeas

+ Tofu

+ Dried fruits, such as prunes, raisins, and apricots

+ Spinach and other dark green leafy vegetables

+ Prune juice

The Nutrition Facts labels on packaged foods will show how much iron the items contain. The amount is given as a percentage of the total amount of iron you need every day.

- Vitamin C

Vitamin C helps the body absorb iron. Good sources of vitamin C are vegetables and fruits, especially citrus fruits. Citrus fruits include oranges, grapefruits, tangerines, and similar fruits. Fresh and frozen fruits, vegetables, and juices usually have more vitamin C than canned ones.

If you’re taking medicines, ask your doctor or pharmacist whether you can eat grapefruit or drink grapefruit juice. Grapefruit can affect the strength of a few medicines and how well they work.

Other fruits rich in vitamin C include kiwi fruit, strawberries, and cantaloupes.

Vegetables rich in vitamin C include broccoli, peppers, Brussels sprouts, tomatoes, cabbage, potatoes, and leafy green vegetables like turnip greens and spinach.

- Treatment To Stop Bleeding

If blood loss is causing iron-deficiency anemia, treatment will depend on the cause of the bleeding. For example, if you have a bleeding ulcer, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics and other medicines to treat the ulcer.

If a polyp or cancerous tumor in your intestine is causing bleeding, you may need surgery to remove the growth.

If you have heavy menstrual flow, your doctor may prescribe birth control pills to help reduce your monthly blood flow. In some cases, surgery may be advised.

- Treatments for Severe Iron-Deficiency Anemia

Blood Transfusion

If your iron-deficiency anemia is severe, you may get a transfusion of red blood cells. A blood transfusion is a safe, common procedure in which blood is given to you through an IV line in one of your blood vessels. A transfusion requires careful matching of donated blood with the recipient’s blood.

A transfusion of red blood cells will treat your anemia right away. The red blood cells also give a source of iron that your body can reuse. However, a blood transfusion is only a short-term treatment. Your doctor will need to find and treat the cause of your anemia.

Blood transfusions are usually reserved for people whose anemia puts them at a higher risk for heart problems or other severe health issues.

Iron Therapy

If you have severe anemia, your doctor may recommend iron therapy. For this treatment, iron is injected into a muscle or an intravenous line in one of your blood vessels.

Intravenous iron therapy presents some safety concerns. It must be done in a hospital or clinic by experienced staff. Iron therapy usually is given to people who need iron long-term but can’t take iron supplements by mouth. This therapy also is given to people who need immediate treatment for iron-deficiency anemia.

Iron Supplements

Standard multivitamin tablets do not contain iron and, those that do, are usually labeled as multivitamins with iron. Iron for treatment of iron deficiency is available as various ferrous ion salts (gluconate, sulfate, fumarate), usually in concentrations of 200 to 400 mg per tablet, representing 30 to 100 mg of elemental iron. The typical recommended dose is 100 to 200 mg of elemental iron daily, which may represent 1 to 4 tablets (see Table 1) 7.

Table 1. Concentrations of elemental iron in typical iron tablets

| Salt Form | Typical Dose | Percent Fe | Elemental Iron |

| Ferrous sulfate (desiccated) | 325 mg | 37% | 120 mg |

| Ferrous sulfate (hydrated) | 325 mg | 20% | 64 mg |

| Ferrous fumarate | 300 mg | 33% | 99 mg |

| Ferrous gluconate | 325 mg | 12% | 39 mg |

How Can Iron-Deficiency Anemia Be Prevented ?

Eating a well-balanced diet that includes iron-rich foods may help you prevent iron-deficiency anemia.

Taking iron supplements also may lower your risk for the condition if you’re not able to get enough iron from food. Large amounts of iron can be harmful, so take iron supplements only as your doctor prescribes.

Infants and young children and women are the two groups at highest risk for iron-deficiency anemia. Special measures can help prevent the condition in these groups.

- Infants and Young Children

A baby’s diet can affect his or her risk for iron-deficiency anemia. For example, cow’s milk is low in iron. For this and other reasons, cow’s milk isn’t recommended for babies in their first year. After the first year, you may need to limit the amount of cow’s milk your baby drinks.

Also, babies need more iron as they grow and begin to eat solid foods. Talk with your child’s doctor about a healthy diet and food choices that will help your child get enough iron.

Your child’s doctor may recommend iron drops. However, giving a child too much iron can be harmful. Follow the doctor’s instructions and keep iron supplements and vitamins away from children. Asking for child-proof packages for supplements can help prevent overdosing in children.

Because recent research supports concerns that iron deficiency during infancy and childhood can have long-lasting, negative effects on brain health, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends testing all infants for anemia at 1 year of age.

- Women and Girls

Women of childbearing age may be tested for iron-deficiency anemia, especially if they have:

+ A history of iron-deficiency anemia

+ Heavy blood loss during their monthly periods

+ Other risk factors for iron-deficiency anemia

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed guidelines for who should be screened for iron deficiency, and how often:

+ Girls aged 12 to 18 and women of childbearing age who are not pregnant: Every 5 to 10 years.

+ Women who have risk factors for iron deficiency: Once a year.

+ Pregnant women: At the first prenatal visit.

For pregnant women, medical care during pregnancy usually includes screening for anemia. Also, your doctor may prescribe iron supplements or advise you to eat more iron-rich foods. This not only will help you avoid iron-deficiency anemia, but also may lower your risk of having a low-birth-weight baby.

What are some effects of iron on health ?

Scientists are studying iron to understand how it affects health. Iron’s most important contribution to health is preventing iron deficiency anemia and resulting problems.

- Pregnant women

During pregnancy, the amount of blood in a woman’s body increases, so she needs more iron for herself and her growing baby. Getting too little iron during pregnancy increases a woman’s risk of iron deficiency anemia and her infant’s risk of low birthweight, premature birth, and low levels of iron. Getting too little iron might also harm her infant’s brain development.Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should take an iron supplement as recommended by an obstetrician or other health care provider. - Infants and toddlers

Iron deficiency anemia in infancy can lead to delayed psychological development, social withdrawal, and less ability to pay attention. By age 6 to 9 months, full-term infants could become iron deficient unless they eat iron-enriched solid foods or drink iron-fortified formula. - Anemia of chronic disease

Some chronic diseases—like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and some types of cancer—can interfere with the body’s ability to use its stored iron. Taking more iron from foods or supplements usually does not reduce the resulting anemia of chronic disease because iron is diverted from the blood circulation to storage sites. The main therapy for anemia of chronic disease is treatment of the underlying disease.

Iron Overload

Iron overload usually occurs as a result of a gene mutation that causes the body to absorb more than a healthy amount of iron. Iron overload less often occurs as a complication of other blood disorders, chronic transfusion therapy, chronic hepatitis, or excessive iron ingestion. Simple blood tests can measure the iron levels within your body.

Overdoses of oral iron, whether intentional or accidental, can cause liver injury, largely as a component of iron poisoning. Iron poisoning occurs most common in toddlers (1 to 3 years old) who ingest iron tablets prescribed for adults 7. Toxicity occurs after ingestion of 3 grams or more of ferrous sulfate (approximately 10 tablets, or ~650 mg of elemental iron), with toxic levels being more than 60 mg/kg of elemental iron and fatal levels more than 180 mg/kg. The typical sequence of events is appearance of nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain within 1 to 3 hours of the ingestion, followed by diarrhea, weakness, irritability, lethargy and stupor. Vomitus may be blood streaked or frank hematemesis. The diarrhea is generally fluid and dark (as a result of iron rather than blood). With higher doses, this initial phase is rapidly followed by pallor, hypotension and shock. Both upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding can occur and early changes include metabolic acidosis and coagulopathy. In some instances, there is an improvement after a few hours of symptoms which can then be followed by sudden hemodynamic collapse, cardiogenic shock and severe acidosis that may be fatal. Early intervention (with gastric lavage, fluid replacement and iron chelation) appears to ameliorate the course of injury. Liver toxicity generally arises after 24 hours and may be more common in adults than children. Severe liver toxicity, with jaundice and marked aminotransferase elevations (ALT and AST greater than 25 times ULN), generally occurs only with larger overdoses and high initial serum iron levels (>1000 μg/dL). Jaundice is initially mild, while prolongation of the prothrombin time (or INR) and acidosis arise early. The usual cause of death from iron poisoning is cardiac arrest, but deaths from hepatic failure as well as emergency liver transplantation for iron poisoning have been reported. Cases of liver injury attributed to iron poisoning have ranged from mild-to-moderate in severity (aminotransferase elevations without symptoms) to severe and rapidly fatal injury. The injury from acute exposure is generally self-limited in course and, with supportive management, resolves rapidly within 2 to 4 weeks of onset. Death from cardiac, respiratory or hepatic failure occurs in 1% to 3% of cases. A late complication of iron poisoning is gastric or intestinal obstruction due to strictures caused by the direct gastrointestinal mucosal injury. There is no reason to believe that subsequent use of oral iron in normal amounts is contraindicated.

- Hemochromatosis

An iron overload disease. Iron overload is a serious chronic condition that develops when the body absorbs too much iron over many years and excess iron builds up in organ tissues (for example, heart tissue and liver tissue).

Hemochromatosis is the disease that occurs as a result of significant iron overload. It can have genetic or nongenetic causes. In the United States about one million people have the disease, usually because of a gene mutation. When the disease is genetic, it is called hereditary hemochromatosis 21. In hemochromatosis (hereditary hemochromatosis) that runs in families, your blood relatives— your parents, grandparents, sisters, brothers, or children—may also have it. You can help by telling your blood relatives that you have hemochromatosis and they could have it too. Urge family members to get their iron levels checked by their doctors. The sooner they know whether they have hemochromatosis, the better. People who start treatment early can stay healthy.

Indeed, it’s important for all close family members to get their iron levels tested (parents, grandparents, sisters, brothers, and children) if anyone in the family has hemochromatosis. The earlier family members find out if they have hemochromatosis, the better their chances of leading long, healthy lives.

Hemochromatosis affects everyone differently. Usually symptoms begin during middle age. Some people get sick sooner, others later. Early symptoms may include fatigue, weakness, weight loss, joint pain, or abdominal pain. There is no definite set of symptoms to indicate that a person has too much iron. Diagnosing hemochromatosis is difficult because the symptoms are like the symptoms of many other diseases.

If hemochromatosis is not treated, it can lead to these conditions:

- Liver cancer

- Diabetes

- Heart disease

- Arthritis

- Impotence for men

- Cirrhosis of the liver

- Infertility and premature

- Bronze skin

- Menopause for women

Hemochromatosis can be treated by a phlebotomy, the same procedure that is used when you donate blood. A nurse takes about a pint of blood from a vein in your arm. The procedure takes about an hour. Most people feel just fine, but others feel tired afterwards and like to rest for an hour or so. It’s a good idea to drink liquids (water, milk, or fruit juices) before and after a phlebotomy. Because you will have frequent phlebotomies, your doctor will monitor your health more closely than if you were just donating blood. How often you have phlebotomies and how many you have depends on how much iron has built up in your body. Most people have them once or twice a week for a year or more. You can get a phlebotomy at many blood donation centers, for example, hospitals, clinics, and bloodmobiles.

You must have phlebotomies for the rest of your life. The good news is that after your iron is lowered to a safe level, you will have phlebotomies less often, usually a few times a year.

What else you need to watch out for:

- Vitamin C increases the amount of iron your body absorbs. So, don’t take pills with more than 500 mg of vitamin C per day. Eating foods with vitamin C is fine.

- Don’t take iron pills, supplements, or multivitamin supplements that have iron in them. Eating foods that contain iron is fine.

- Don’t eat raw fish or raw shellfish. Cooking destroys germs harmful to people with hemochromatosis.

- Stay away from alcohol.

Can iron be harmful ?

Yes, iron can be harmful if you get too much. In healthy people, taking high doses of iron supplements (especially on an empty stomach) can cause an upset stomach, constipation, nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, and fainting. High doses of iron can also decrease zinc absorption. Extremely high doses of iron (in the hundreds or thousands of mg) can cause organ failure, coma, convulsions, and death. Child-proof packaging and warning labels on iron supplements have greatly reduced the number of accidental iron poisonings in children.

Some people have an inherited condition called hemochromatosis that causes toxic levels of iron to build up in their bodies. Without medical treatment, people with hereditary hemochromatosis can develop serious problems like liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, and heart disease. People with this disorder should avoid using iron supplements and vitamin C supplements.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. Iron. https://medlineplus.gov/iron.html#cat_51[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations to Prevent and Control Iron Deficiency in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00051880.htm[↩][↩]

- Wessling-Resnick M. Iron. In: Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL, Ziegler RG, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 11th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:176-88.[↩][↩]

- Aggett PJ. Iron. In: Erdman JW, Macdonald IA, Zeisel SH, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 10th ed. Washington, DC: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:506-20.[↩][↩][↩]

- Murray-Kolbe LE, Beard J. Iron. In: Coates PM, Betz JM, Blackman MR, et al., eds. Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. 2nd ed. London and New York: Informa Healthcare; 2010:432-8.[↩][↩]

- Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the Iron-Infection Axis. Science 2012;338:768-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23139325[↩]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Iron. https://livertox.nlm.nih.gov/Iron.htm[↩][↩][↩]

- Gibson RS. Assessment of Iron Status. In: Principles of Nutritional Assessment. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005:443-76.[↩]

- World Health Organization. Report: Priorities in the Assessment of Vitamin A and Iron Status in Populations, Panama City, Panama, 15-17 September 2010. Geneva; 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75334/1/9789241504225_eng.pdf[↩]

- Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc : a Report of the Panel on Micronutrients. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. https://www.nap.edu/read/10026/chapter/1[↩][↩]

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003646.htm[↩]

- Hurrell R, Egli I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1461S-7S. http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/91/5/1461S.long[↩]

- Rutzke CJ, Glahn RP, Rutzke MA, Welch RM, Langhans RW, Albright LD, et al. Bioavailability of iron from spinach using an in vitro/human Caco-2 cell bioassay model. Habitation 2004;10:7-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15880905[↩]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 27. Nutrient Data Laboratory home page, 2014. https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/[↩]

- Haas JD, Brownlie T IV. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J Nutr 2001;131:676S–690S.[↩]

- Grantham-McGregor S, Ani C. A review of studies on the effect of iron deficiency on cognitive development in children. J Nutr 2001;131:649S–668S.[↩]

- Rasmussen KM. Is there a causal relationship between iron deficiency or iron-deficiency anemia and weight at birth, length of gestation and perinatal mortality? J Nutr 2001;131:590S–603S.[↩]

- Looker AC, Dallman PR, Carroll MD, Gunter EW, Johnson CL. Prevalence of iron deficiency in the United States. JAMA 1997;277:973–6.[↩][↩]

- CDC. Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. MMWR 1998;47(No. RR-3). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00051880.htm[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Iron Deficiency — United States, 1999–2000. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5140a1.htm[↩]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hemochromatosis. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5763/cdc_5763_DS1.pdf[↩]