Leydig cell tumor

Leydig cell tumor is a rare testicular tumors of the male gonadal interstitium that may be hormonally active and lead to feminizing or virilizing syndromes 1. Although leydig cell tumors usually secrete testosterone, the production of estrogen, progesterone, and corticosteroids has also been described. Estrogen excess and feminizing syndromes may occur from the peripheral aromatization of testosterone or from the direct production of estradiol by the tumor itself. Leydig cell tumors comprise 1-3% of all testicular neoplasms. Leydig cell tumors can be pure or can be mixed with other sex cord-stromal or germ cell tumors. Leydig cell tumors are usually benign, but appproximately 10% are malignant 2. The malignant variants occur only in adults.

Leydig cell tumors are most commonly found in males. Nonetheless, these tumors have been well-described in the ovarian stroma of females, who may present with signs and symptoms of virilization (a condition in which women develop male-pattern hair growth and other masculine physical traits). Ovarian Sertoli Leydig cell tumors are usually malignant, unlike Leydig cell tumors found in males.

Leydig cell tumors may occur in prepubertal boys but are most common in men aged 30-60 years 3. In a report of 12 patients with Leydig cell tumors (aged 4.2–14.7 years), precocious puberty was the presenting symptom in 7 of 12 patients 4.

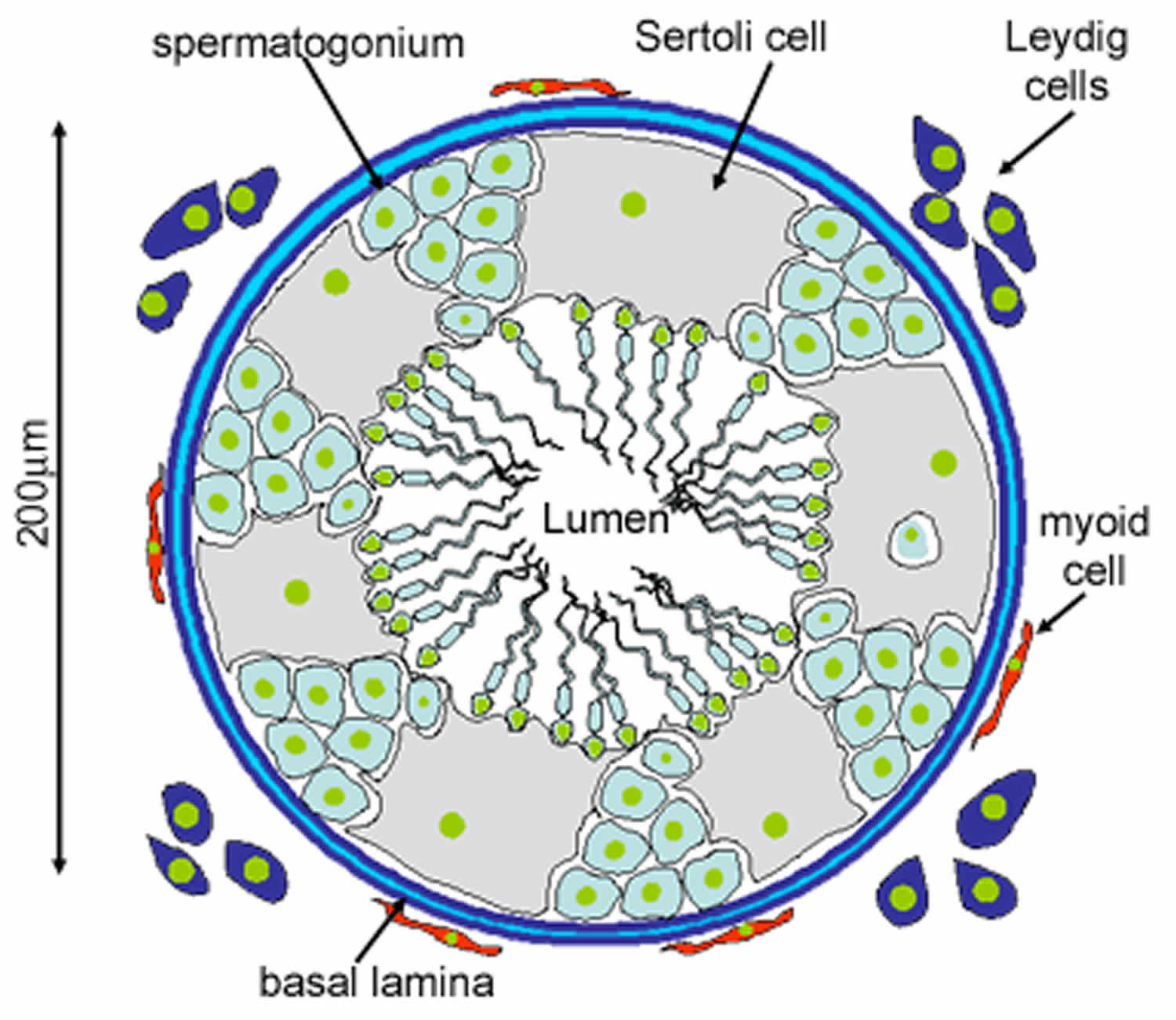

Leydig cells are located within the interstitium of the testis, between the seminiferous tubules, and produce testosterone in response to luteinizing hormone. Through their hormonal balance, these cells play an important role in the development of secondary male characteristics and spermatogenesis.

As with germ cell tumors, the route of spread is hematogenous and lymphatic to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Unlike germ cell tumors, however, Leydig cell tumors show relative lack of sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy agents 5.

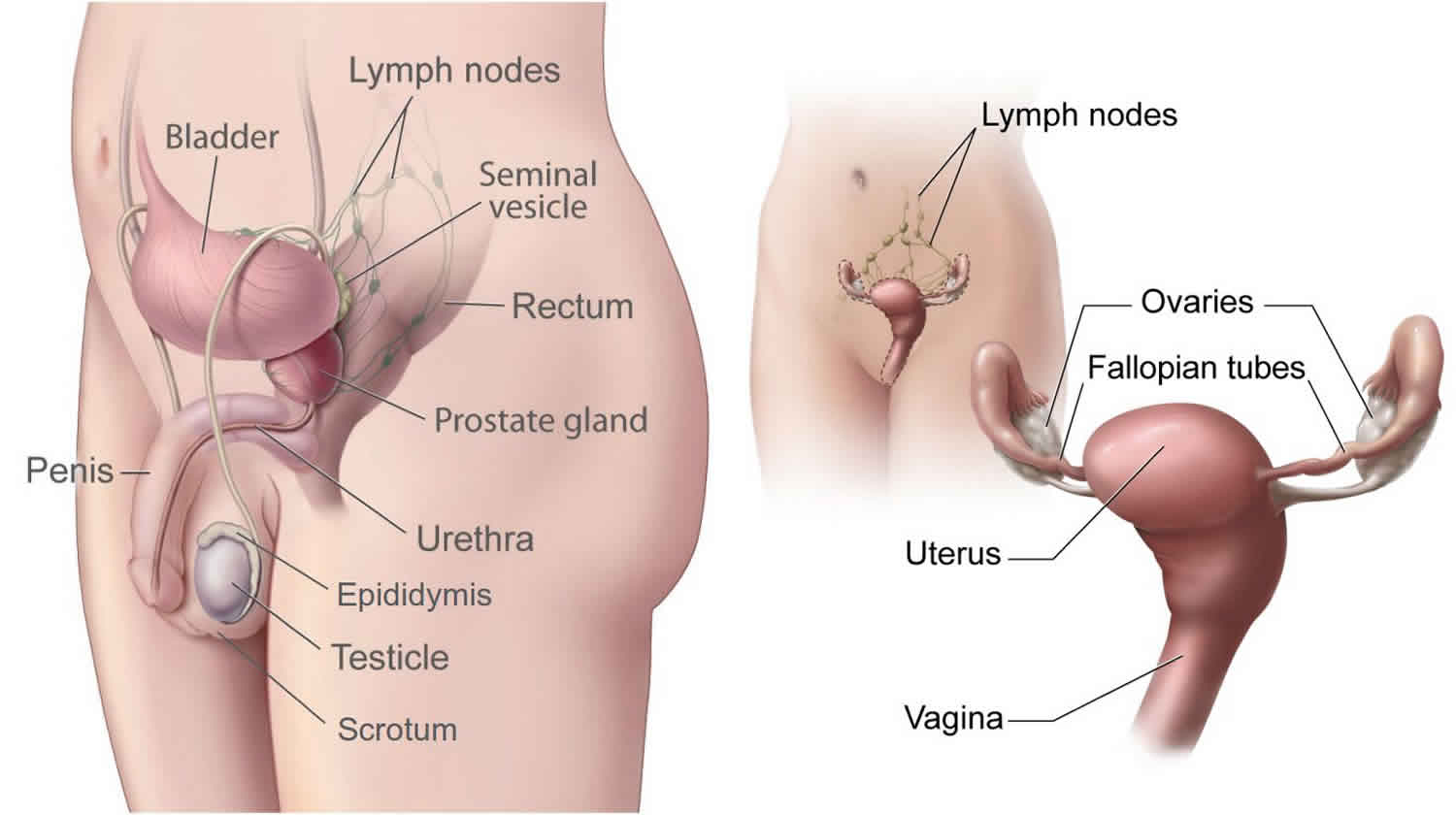

Male reproductive system

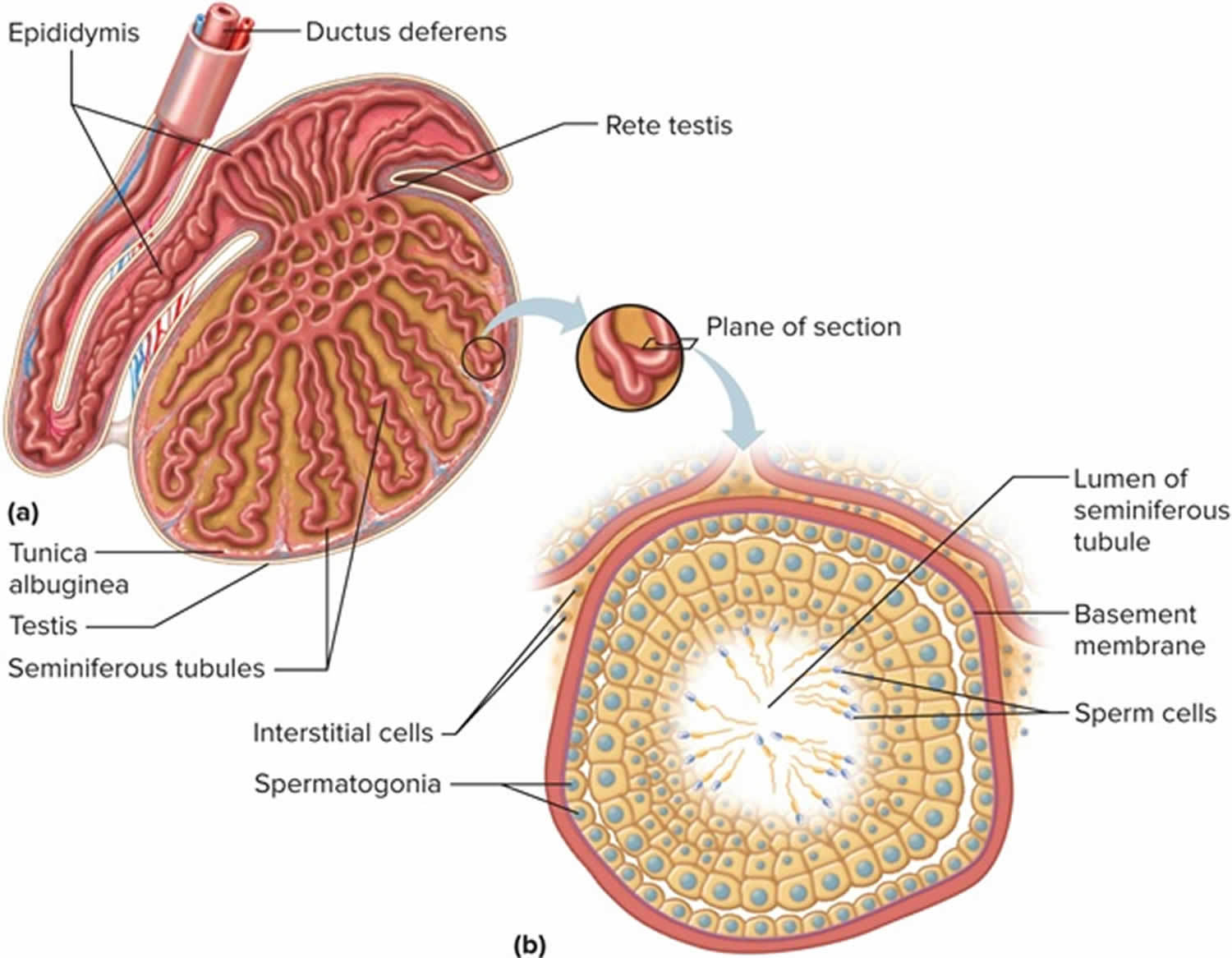

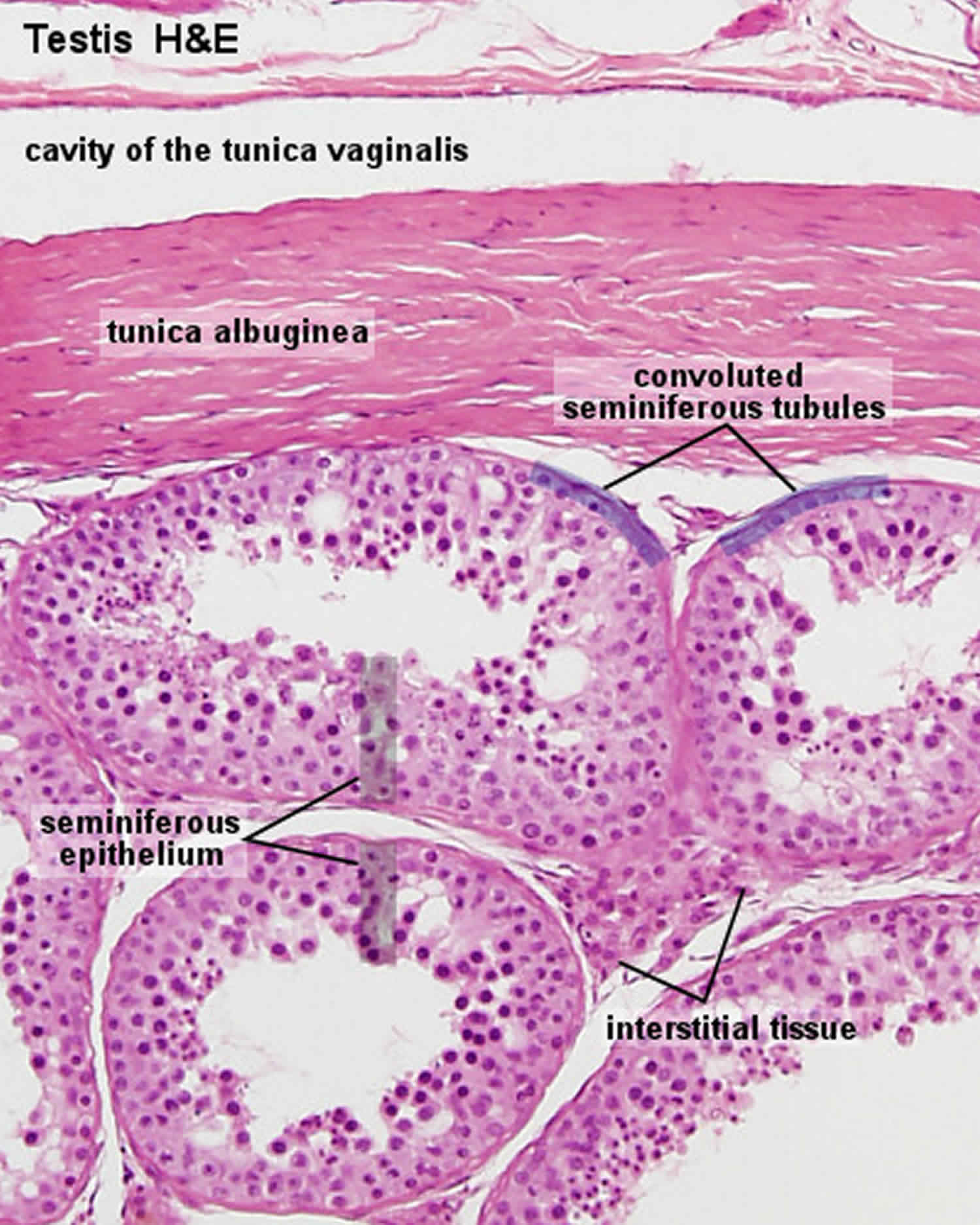

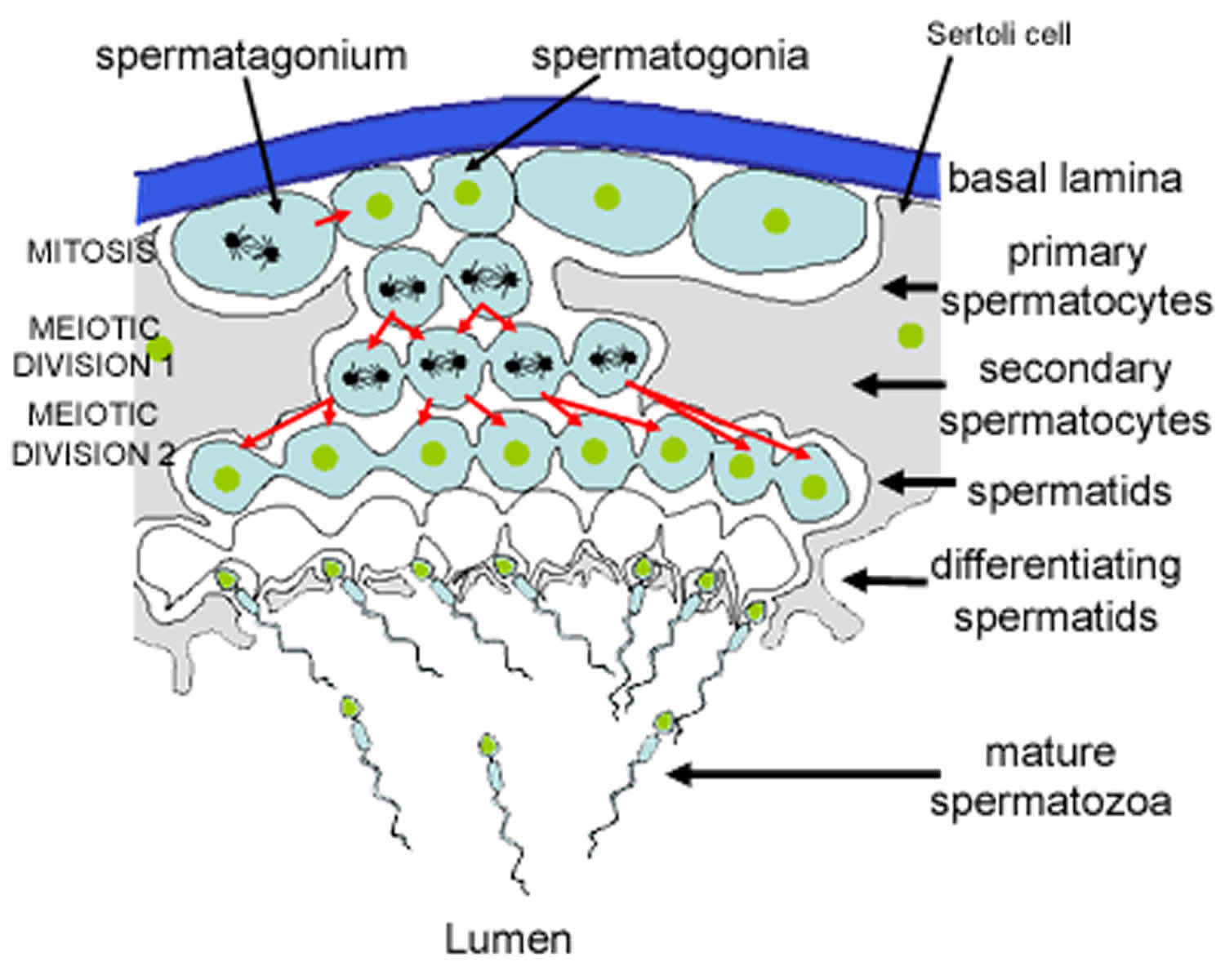

Spermatogenesis takes place in the seminiferous tubules. This includes mitosis and meosis to form haploid gametes, followed by maturation to form spermatocytes (called spermiogenesis). The stages that a developing spermatogonium passes through as it develops and matures to form a mature spermatozoon are covered in more detail here.

The seminiferous tubules are lined by a complex stratified epithelium containing two distinct populations of cells, spermatogenic cells, that develop into spermatozoa, and Sertoli cells which have a supportive and nutrient function.

Figure 1. Testis

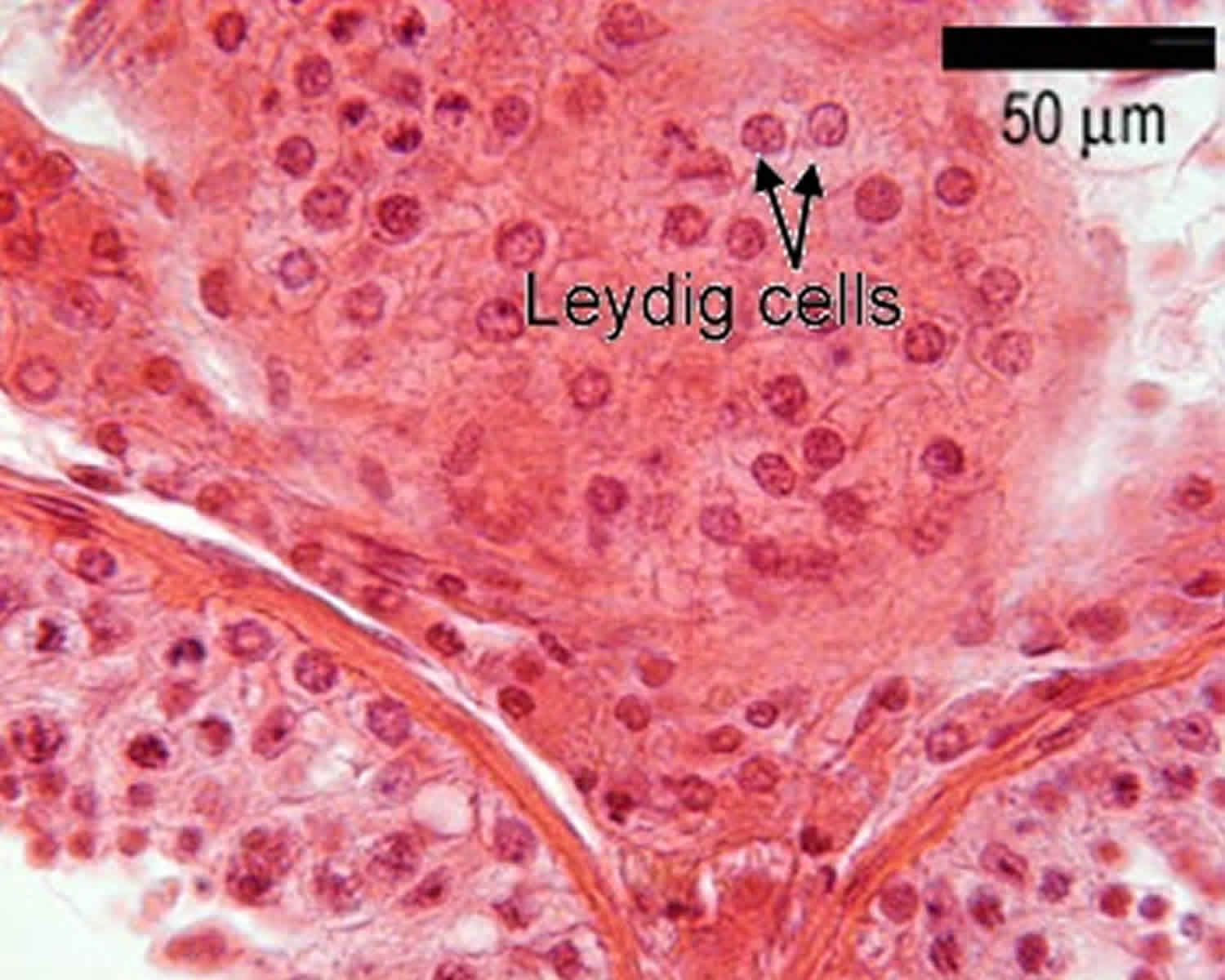

Figure 2. Seminiferous tubules

Footnote: This diagram shows a single seminiferous tubule, and cells in the interstitial tissue outside the tubule. In thisconnective tissue between the seminiferous tubules there are large cells with eosinophilllic cytoplasm called Leydig cells. There are also cells called myoid cells surrounding the basement membrane, which are squamous contractile cells, and generate peristaltic waves in the tubules.

Figure 3. Formation of spermatozoa (sperm)

Footnote: This is a schematic diagram of part of a seminiferous tubule, showing the stages in the formation of spermatozoa.

Leydig cells

Leydig cells are ‘interstitial’ cells (as they lie between the tubules). They have pale cytoplasm because they contain many cholesterol-lipid droplets. The Leydig cells make and secrete testosterone, in response to lutenising hormone from the pituitary. The cholesterol is used in the first step of testosterone production.

Testosterone promotes production of spermatozoa, secretion from the accessory sex glands, and acquisition of male secondary characteristics. This process does not start until puberty when luteinising hormone (LH) stimulates the Leydig cells to produce testosterone.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates the Sertoli cells to secrete androgen-binding protein into the lumen of the seminiferous tubules. Binding of testosterone in the lumen provides a local testosterone supply for the developing permatogonia.

Figure 4. Leydig cells

Sertoli cells

Sertoli cells are the epithelial supporting cells of the seminiferous tubules. They are derived from the epithelial sex cords of the developing gonads. They are tall simple columnar cells, which span from the basement membrane to the lumen. They surround the proliferating and differentiating germ cells forming pockets around these cells, providing nutrients, and phagocytosing excess spermatid cytoplasm, not needed in forming the spermatozoa.

They are connected to each other by continuous tight junctions that seal the tubule into two compartments: the basal (close to the basal lamina) and adluminal (towards the lumen) compartment. Large molecules cannot pass between the basal and adluminal compartment – this is called the blood-testis barrier.

Like all epithelial cells, the Sertoli cells are avascular. Sertoli cells suport the germ cell progenitors and help to transfer nutrients from the nearby capillaries. The developing spermatogonia rely on the Sertoli cells for all of their nourishment. The blood-testis barrier formed by the Sertoli cells effectively isolates the developing spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids and mature spermatozoa from blood. Differentiating spermatozoa nestle in pockets in the peripheral cytoplasm of these cells.

Sertoli cells also produce testicular fluid, including a protein that binds to and concentrates testosterone, which is essential for the development of the spermatozoa. They also help to translocate the differentiating cells to the lumen, and phagocytose degenerating germ cells and surplus cytoplasm remaining from spermiogenesis.

Blood-testis barrier

Importantly, the basal regions of the lateral borders of the Sertoli cells are connected to each other by continuous tight junctions. These divide the tubules into two separate compartments. The mitotic spermatogonia remain in the basal compartment. Differentiating progeny enter the adluminal compartment, and are sealed off from the basal compartment. If novel antigens are expressed on the haploid cells, then it is less likely that they will be detected by the immune system in this sealed off compartment. The developing cells are also in a very protective environment.

Leydig cell tumor causes

The cause of Leydig cell tumors remains unknown. Unlike germ cell testicular tumors, Leydig cell neoplasms are not associated with undescended testicle (cryptorchidism). It is thought that an endocrine role may contribute to the development of these tumors. For example, an excessive stimulation of Leydig cells with luteinizing hormone due to a disorder of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis may induce their oncogenesis. Animal models have also demonstrated Leydig cell tumorigenesis following long-term estrogen administration 6.

Leydig cell tumor prevention

Performing testicular self-examination each month may help detect testicular cancer at an early stage, before it spreads. Finding testicular cancer early is important for successful treatment and survival.

Leydig cell tumor symptoms

In most Leydig cell tumor cases, patients present with an incidental finding of a testicular mass on scrotal ultrasonography during evaluation of hydroceles or varicoceles or during workup of other conditions (eg, infertility). A nontender palpable testicular mass or nodule may be noted.

Prepubertal boys with androgen-secreting tumors may present with precocious puberty; features may include prominent external genitalia, pubic hair growth, accelerated skeletal and muscle development, and mature masculine voice. Boys with estrogen-secreting tumors may present with feminizing symptoms such as gynecomastia, breast tenderness, and gonadogenital underdevelopment.

Adults with androgen-secreting tumors are generally asymptomatic. In adults with estrogen-secreting tumors, symptoms such as loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, and infertility have been reported.

Clinical manifestations of leydig cell tumor include the following:

- A nontender palpable testicular mass or nodule

- Precocious puberty in prepubertal boys with androgen-secreting tumors

- Feminizing symptoms in boys with estrogen-secreting tumors

Adults with androgen-secreting leydig cell tumors are generally asymptomatic. Manifestations in adults with estrogen-secreting tumors include the following:

- Loss of libido

- Erectile dysfunction

- Infertility

- Gynecomastia

- Feminine hair distribution

- Gonadogenital atrophy

Leydig cell tumors may be an incidental finding of a testicular mass on scrotal ultrasonography performed for other conditions.

Leydig cell tumor diagnosis

Serum testosterone levels are usually elevated; however, serum estradiol levels may also be increased, especially when feminization is evident. Results of the following laboratory studies are normal in patients with pure Leydig cell tumors:

- Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

- Beta human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- Urine ketosteroids

- Plasma cortisol

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test

- Dexamethasone suppression test

Levels of testicular tumor markers such as serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) should be within the reference range in pure Leydig cell tumors.

The steroid secretion of Leydig cell tumors varies. Serum testosterone levels are usually elevated; however, serum estradiol levels may also be increased, especially when feminization is evident.

Urine and serum endocrinological tests such as urine ketosteroids, plasma cortisol, or the dexamethasone suppression test may help differentiate Leydig cell tumors from other adrenocortical disorders. Leydig cell tumor endocrine function is independent of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal hormonal axis and should not demonstrate a response to adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation or dexamethasone suppression.

Imaging studies

- Scrotal ultrasonography: Confirms the diagnosis, especially when physical examination findings are equivocal 7

- Magnetic resonance imaging: Can reveal small nonpalpable Leydig cell tumors that are not visible on ultrasound.

- CT scanning of the abdomen and chest radiography: Indicated if malignancy is suspected

Scrotal ultrasonography is typically performed to confirm the diagnosis, especially in patients in whom the physical examination findings are equivocal 7. On color Doppler ultrasonography, a typical Leydig cell tumor appears as a round, infracentimeter hyperechoic mass with a clear delineation from the surroundings; lobulated margins are seen in up to 50% of cases 8

MRI can reveal small nonpalpable Leydig cell tumors not otherwise visible on sonograms. On T1-weighed imaging, the tumors are not visible before administration of contrast agents, since they have similar signal intensity as normal testicular parenchyma. They appear with marked enhancement after intravenous injection of contrast material. Other testicular tumors do not show a similar pattern of enhancement 9.

CT scanning of the abdomen and chest radiography are indicated if malignancy is suspected.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is a possible future imaging technique for Leydig cell tumors. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound demonstrates hypervascularization in these cases. In CEUS, Leydig cell tumor is suggested by findings of a short filling time or by a circumferential vessel with rapid centripetal filling 10.

Leydig cell tumor treatment

Leydig cell tumors have been primarily managed with radical orchiectomy and it remains in use for malignant cases. However, testis-sparing surgery with enucleation of the mass is increasingly being reported for benign cases, in both the adult and pediatric populations 11. In testisi-sparing surgery, the mass is enucleated with a small surrounding edge of testicular parenchyma and immediately sent for frozen section analysis. Frozen section examination successfully discriminated between benign and malignant neoplastic lesions in a study of 86 patients with testicular nodules, including five patients with Leydig cell tumors and six patients with Leydig cell hyperplasia 12.

When Leydig cell tumors are diagnosed and treated early, testicle-sparing surgery has proved to be a feasible and safe choice and could be regarded as first-line therapy. In a study of 20 patients with Leydig cell tumors who were treated with conservative surgery, follow-up for a mean of 15 years found 100% disease-free survival, with no local recurrences or metastases. Patients ranged in age from 5 to 61 years 13. Frozen section examination during surgery is key.

Additional frozen sections of the tumor bed can be assessed and/or a radical inguinal orchiectomy can be performed if malignancy is subsequently suspected. If the tumor appears malignant, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection is also recommended.

Further outpatient care

Observation is sufficient in patients with a benign Leydig cell tumortreated with radical inguinal orchiectomy.

Patients with malignant tumors require regular follow-up imaging, including CT scanning of the chest and abdomen. Metastases most frequently involve the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Other reported metastatic sites include the liver (45%), lungs (40%), and bone (25%).

The ideal frequency of subsequent abdominal CT scanning and chest imaging is poorly defined. However, a reasonable follow-up protocol includes a chest imaging study and abdominal CT scanning every 4 months during the first year, followed by similar imaging at 6-month intervals during the second year and yearly examinations thereafter 13.

Late onset of metastasis, up to 8 years after orchiectomy, has been reported. This supports the recommendation of long-term tumor surveillance, continuing for 10-15 years after surgery.

Leydig cell tumor prognosis

Patients with benign Leydig cell tumors have an excellent prognosis. In contrast, the mean survival in patients with a malignant variant is 2-3 years.

Advanced patient age is associated with a poorer prognosis. Pathologic risk factors for occult metastatic disease include the following 14:

- Tumor diameter >5 cm

- Positive margins or rete testis invasion

- Lymphovascular invasion

- Cellular atypia

- Necrosis

- Increased mitotic rate (≥5 mitoses per high-power field)

A systematic review of pathologic risk factors found that the risk of occult metastatic disease increased with each additional risk factor. Five-year occult metastatic disease-free survival was 98.1% for patients with fewer than two risk factors vs 44.9% for those with two or more risk factors 15.

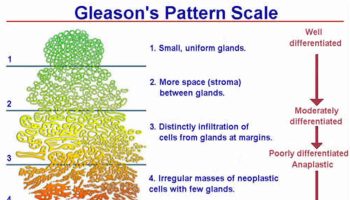

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is a very rare ovarian neoplasm belonging to the subgroup of sex cord-stromal tumors, with a worldwide incidence rate of <0.5% 16. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor can be classified as benign or malignant according to the degree of differentiation, and its prognosis is correlated with the tumor’s stage and differentiation 17. Therefore, prompt detection and surgical removal of the tumor are pivotal in determining patient’s prognosis.

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is mostly confined to the ovaries, unilateral, form large masses, and presents most commonly (approximately 75%) in females in their third and fourth decades, but Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor can affect females of all ages.

As the Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor comprises a testicular structure, it often results in overproduction of androgens (testosterone); therefore, overt androgenic effects occur in approximately 30% of patients; clinical symptoms, such as hirsutism, thickening of voice, and male patterns of fat distribution may also occur 18. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor may be suspected if the clinical manifestation is virilization or the plasma testosterone level is >6.5 nmol/L 16. Mostly, conventional radiologic imaging studies can localize Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor when the size of the tumor mass is significant. However, some tumors may be too small to localize and make an appropriate differential diagnosis before surgical exploration.

Although Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor often secretes androgen and androgen precursors, clinical manifestation of virilization occurs in only approximately 30% of patients 18. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor cells produce and release a male sex hormone called testosterone.

Histologically, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor can be described as either well differentiated, intermediately differentiated, and poorly differentiated, with each level of differentiation indicating its own respective prognoses 18.

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor causes

The exact cause of ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is not known. Changes (mutations) in genes may play a role.

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor symptoms

Sertoli leydig cell tumor starts in the female ovaries, mostly in one ovary. The cancer cells release a male sex hormone (testosterone). As a result, the woman may develop symptoms such as:

- A deep voice

- Enlarged clitoris

- Facial hair

- Loss in breast size

- Stopping of menstrual periods

Pain in the lower belly (pelvic area) is another symptom. It occurs due to the tumor pressing on nearby structures.

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor diagnosis

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam and a pelvic exam, and ask about the symptoms.

Tests will be ordered to check the levels of female and male hormones, including testosterone.

An ultrasound or CT scan will likely be done to find out where the tumor is and its size and shape.

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor treatment

Surgery is done to remove one or both ovaries. Total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended in patients with no future pregnancy plans 17. Otherwise, unilateral oophorectomy can be performed for those who wanted to preserve their fertility.

If the tumor is advanced stage, chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be done after surgery.

Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor prognosis

Early treatment results in a good outcome with a favorable prognosis with an overall 5-year survival rate of 70–90% 17. Feminine characteristics usually return after surgery. But male characteristics resolve more slowly.

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor has been found to cause either recurrence or metastasis in 18% of patients 18. For more advanced stage tumors, outlook is less positive. In general, periodic follow-up of hormone levels including testosterone and initially elevated tumor markers are recommended after the surgical removal of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. Moreover, measurement of serum inhibin or calretinin levels may be helpful 19. PET-CT in conjunction with these tumor markers may have an additional value in detecting early tumor recurrence or distant metastasis especially for poorly differentiated tumors.

- Leydig Cell Tumors. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/437020-overview[↩]

- [Guideline] Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bokemeyer C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Fizazi K, et al. Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2015 Update. Eur Urol. 2015 Dec. 68 (6):1054-68.[↩]

- Carmignani L, Colombo R, Gadda F, et al.: Conservative surgical therapy for leydig cell tumor. J Urol 178 (2): 507-11; discussion 511, 2007.[↩]

- Luckie TM, Danzig M, Zhou S, et al.: A Multicenter Retrospective Review of Pediatric Leydig Cell Tumor of the Testis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 41 (1): 74-76, 2019.[↩]

- Farkas LM, Székely JG, Pusztai C, Baki M. High frequency of metastatic Leydig cell testicular tumours. Oncology. 2000 Aug. 59 (2):118-21.[↩]

- Basciani S, Brama M, Mariani S, De Luca G, Arizzi M, Vesci L, et al. Imatinib mesylate inhibits Leydig cell tumor growth: evidence for in vitro and in vivo activity. Cancer Res. 2005 Mar 1. 65(5):1897-903.[↩]

- Leonhartsberger N, Ramoner R, Aigner F, Stoehr B, Pichler R, Zangerl F, et al. Increased incidence of Leydig cell tumours of the testis in the era of improved imaging techniques. BJU Int. 2011 Nov. 108(10):1603-7.[↩][↩]

- Maxwell F, Izard V, Ferlicot S, Rachas A, Correas JM, Benoit G, et al. Colour Doppler and ultrasound characteristics of testicular Leydig cell tumours. Br J Radiol. 2016 Jun. 89 (1062):20160089[↩]

- Tsitouridis I, Maskalidis C, Panagiotidou D, Kariki EP. Eleven patients with testicular leydig cell tumors: clinical, imaging, and pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Oct. 33 (10):1855-64.[↩]

- Lock G, Schröder C, Schmidt C, Anheuser P, Loening T, Dieckmann KP. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound and real-time elastography for the diagnosis of benign Leydig cell tumors of the testis – a single center report on 13 cases. Ultraschall Med. 2014 Dec. 35 (6):534-9.[↩]

- Carmignani L, Colombo R, Gadda F, Galasso G, Lania A, Palou J, et al. Conservative surgical therapy for leydig cell tumor. J Urol. 2007 Aug. 178(2):507-11; discussion 511.[↩]

- Bozzini G, Rubino B, Maruccia S, Marenghi C, Casellato S, Picozzi S, et al. Role of frozen section examination in the management of testicular nodules: a useful procedure to identify benign lesions. Urol J. 2014 Jul 8. 11(3):1687-91.[↩]

- Bozzini G, Picozzi S, Gadda F, Colombo R, Decobelli O, Palou J, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up Using Testicle-Sparing Surgery for Leydig Cell Tumor. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2013 Jan 10.[↩][↩]

- Cheville JC. Classification and pathology of testicular germ cell and sex cord-stromal tumors. Urol Clin North Am. 1999 Aug. 26(3):595-609.[↩]

- Rove KO, Maroni PD, Cost CR, Fairclough DL, Giannarini G, Harris AK, et al. Pathologic Risk Factors for Metastatic Disease in Postpubertal Patients With Clinical Stage I Testicular Stromal Tumors. Urology. 2016 Aug 15.[↩]

- Gui T, Cao D, Shen K, Yang J, Zhang Y, Yu Q, et al. A clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:384–389.[↩][↩]

- Kong J, Park YM, Choi YS, Cho S, Lee BS, Park JH. Diagnosis of an indistinct Leydig cell tumor by positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62(3):194–198. doi:10.5468/ogs.2019.62.3.194 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6520550[↩][↩][↩]

- Young RH, Scully RE. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. A clinicopathological analysis of 207 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:543–569.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Zhang HY, Zhu JE, Huang W, Zhu J. Clinicopathologic features of ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:6956–6964.[↩]