What is pulmonic stenosis

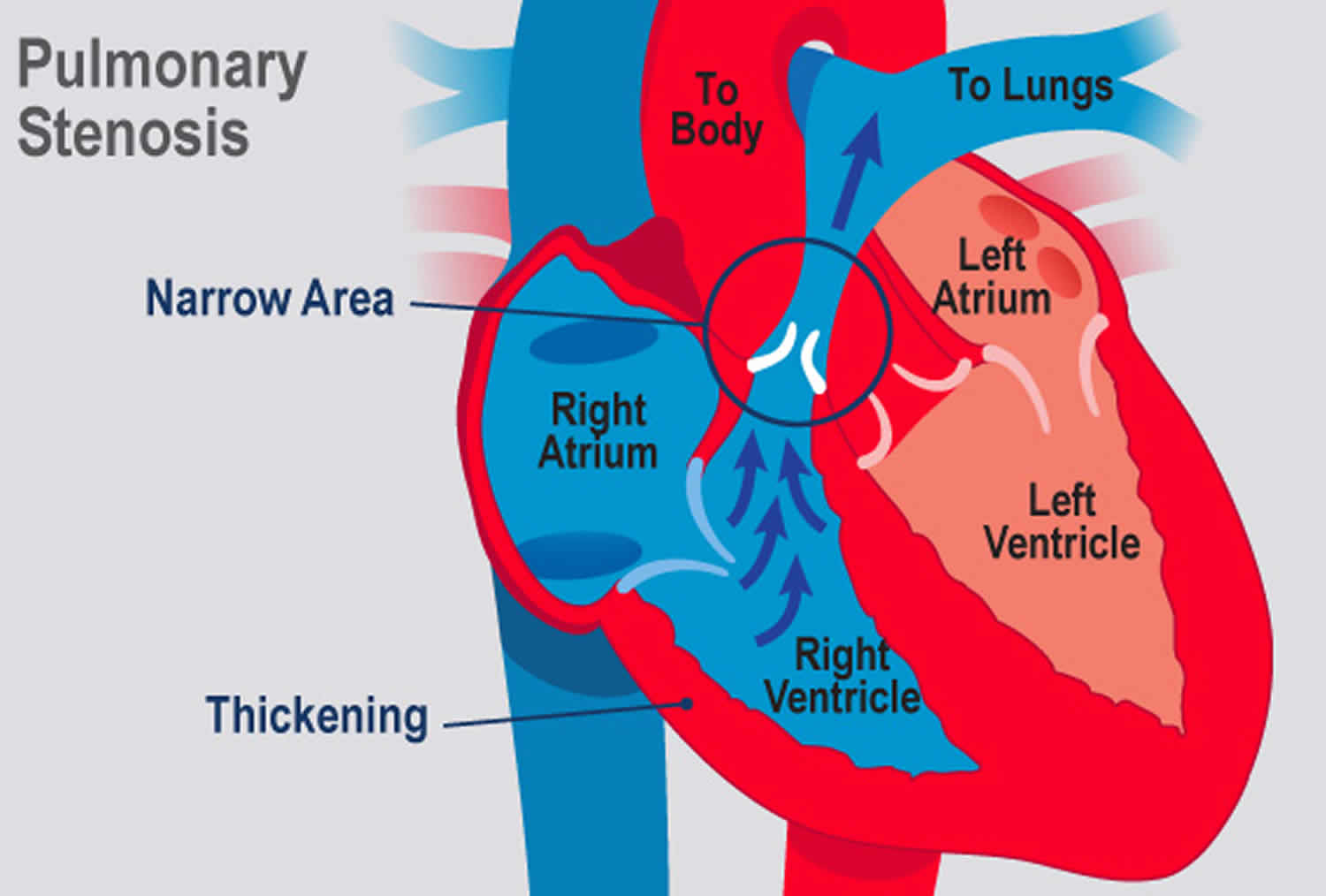

Pulmonic stenosis refers to a dynamic or fixed anatomic obstruction to blood outflow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery during systole 1. Most cases are congenital; many remain asymptomatic until adulthood. Signs include a crescendo-decrescendo ejection murmur. Although most commonly diagnosed and treated in the pediatric population, individuals with complex congenital heart disease and more severe forms of isolated pulmonic stenosis are surviving into adulthood and require ongoing assessment and cardiovascular care 2. Pulmonic stenosis diagnosis is by echocardiography. Symptomatic patients and those with large gradients require balloon valvuloplasty.

Pulmonic stenosis types

Pulmonic stenosis can be due to isolated valvular (90%), subvalvular, or peripheral (supravalvular) obstruction, or it may be found in association with more complicated congenital heart disorders.

Valvular pulmonic stenosis

Isolated valvular pulmonic stenosis comprises approximately 10% of all congenital heart disease. Typically, the valve commissures are partially fused and the 3 leaflets are thin and pliant, resulting in a conical or dome-shaped structure with a narrowed central orifice. Poststenotic pulmonary artery dilatation may occur owing to “jet-effect” hemodynamics.

Alternatively, approximately 10-15% of individuals with valvar pulmonic stenosis have dysplastic pulmonic valves. These valves have irregularly shaped, thickened leaflets, with little, if any, commissural fusion, and they exhibit variably reduced mobility. The leaflets are composed of myxomatous tissue, which may extend to the vessel wall. The valve annulus is usually small, and the supravalvular area of the pulmonary trunk is usually hypoplastic. Poststenotic dilatation of the pulmonary artery is uncommon. Approximately two thirds of patients with Noonan syndrome have pulmonic stenosis due to dysplastic valves.

A bicuspid valve is found in as many as 90% of patients with tetralogy of Fallot, whereas it is rare in individuals with isolated valvar pulmonic stenosis.

With severe valvular pulmonic stenosis, subvalvular right ventricular hypertrophy can cause infundibular narrowing and contribute to the right ventricular outflow obstruction. This often regresses after correction of valvular stenosis.

With severe pulmonic stenosis and decreased right ventricular chamber compliance, cyanosis can occur from right-to-left shunting if a concomitant patent foramen ovale, atrial septal defect, or ventricular septal defect is present.

Subvalvular pulmonic stenosis

Subvalvular pulmonic stenosis occurs as a narrowing of the infundibular or subinfundibular region, often with a normal pulmonic valve. This condition is present in individuals with tetralogy of Fallot and can also be associated with a ventricular septal defect (VSD).

Double-chambered right ventricle is a rare condition associated with fibromuscular narrowing of the right ventricular outflow tract with right ventricular outflow obstruction at the subvalvular level.

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis can cause obstruction at the level of the main pulmonary artery, at its bifurcation, or at the more distal branches. Ppulmonic stenosis may occur at a single level, but multiple sites of obstruction are more common. Peripheral pulmonary stenosis may be associated with other congenital heart anomalies such as valvular pulmonic stenosis, atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA); 20% of the patients with tetralogy of Fallot have associated peripheral pulmonary stenosis.

Functional or physiologic peripheral pulmonary stenosis is a common cause of a systolic murmur in infants. It occurs in both premature and full-term infants; with time, the pulmonary artery grows, and the murmur usually disappears within a few months.

Poststenotic dilatation occurs with discrete segmental stenosis but is absent if the stenotic segment is long or if the pulmonary artery is diffusely hypoplastic.

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis is associated with various inherited and acquired conditions including rubella and the Alagille, cutaneous laxa, Noonan, Ehlers-Danlos, and Williams syndromes.

Pulmonic stenosis causes

Pulmonic stenosis is most often a form of congenital heart disease and affects predominantly children; stenosis may be valvular or just below the valve in the outflow tract (infundibular). It commonly is a component of tetralogy of Fallot. Isolated valvular pulmonic stenosis comprises approximately 10% of all congenital heart disease.

Less common causes are Noonan syndrome (a familial syndrome similar to Turner syndrome but with no chromosomal defect) and carcinoid syndrome in adults. Carcinoid may result in development of myxomatous plaques in the right ventricle outflow tract, with distortion and constriction of the pulmonic ring, as well as fusion or destruction of pulmonary valve leaflets, resulting in both stenosis and regurgitation.

Other forms of acquired pulmonic stenosis include the following:

- Pulmonic stenosis is a rare manifestation of rheumatic heart disease, and it follows involvement of the mitral and aortic valves.

- Rarely, cardiac tumors can grow on or into the right ventricle outflow tract and cause flow obstruction.

- Sinus of Valsalva aneurysms and aortic graft aneurysms are extracardiac entities that can cause pulmonic stenosis by external compression.

Pulmonic stenosis symptoms

Many children with pulmonic stenosis remain asymptomatic for years and do not present to a physician until adulthood. Even then many patients remain asymptomatic. When symptoms of pulmonic stenosis develop, they resemble those of aortic stenosis (syncope, angina, dyspnea). Those with severe pulmonic stenosis may experience exertional dyspnea and fatigue. In extremely rare cases, patients present with exertional angina, syncope, or sudden death.

Peripheral edema and other typical symptoms occur with right heart failure.

Cyanosis is present in those with significant right-to-left shunt via a patent foramen ovale, atrial septal defect, or ventricular septal defect.

Pulmonic stenosis in pregnancy

Valvular heart disease, including pulmonic stenosis, should warrant follow-up care by a high-risk obstetrics team. The hemodynamic changes in pregnancy—which include increase in plasma volume proportionally greater than red blood cell volume, increase in cardiac stroke volume, decrease in systemic vascular resistance, decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance with a drop in pulmonary pressures, and decrease in venous return that is more marked in the third trimester—can exacerbate the symptoms of pulmonic stenosis.

In general, pregnancy is tolerated well by individuals who have asymptomatic pulmonic stenosis before conception, even if the degree of stenosis is severe.

When symptoms are referable to pulmonic stenosis, they are similar to those of individuals who are not pregnant and symptomatic. The symptoms of healthy pregnancy can resemble those of pulmonic stenosis, including exertional fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, presyncope, and, rarely, frank syncope. Palpitations due to arrhythmias have been noted to be more common in those with pulmonic stenosis.

Mild pulmonic stenosis produces a murmur similar to that of the benign flow murmur of pregnancy, which typically increases in intensity as the stroke volume is augmented. During the physical examination, this murmur can be distinguished from the flow murmur of pregnancy by noting a prominent jugular venous a wave, an RV lift, a systolic thrill over the pulmonic area, a pulmonic ejection click, and a diminished or absent P2. ECG and echocardiographic evaluation are essential in confirming clinical suspicion. Fetal echocardiography is indicated in patients with pulmonic stenosis or tetralogy of Fallot.

Treatment in pregnancy

Avoidance of vigorous exercise is recommended, especially during the second half of pregnancy in patients with moderate-to-severe gradients.

Balloon valvuloplasty is recommended in nonpregnant patients when the gradient across the right ventricular outflow track is greater than 50 mm Hg at rest or when the patient is symptomatic.

If severe pulmonic stenosis is detected during pregnancy, percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty to relieve the obstruction usually can be accomplished safely, obviating the need to terminate the pregnancy.

Arrhythmias are treated according to the severity of symptoms.

Activity

Avoidance of vigorous exercise in pregnancy is recommended, especially during the second half of pregnancy in patients with moderate or severe gradients.

One study found that pregnant patients with pulmonary stenosis had favorable outcomes and low maternal and fetal complications. This is in contrast to left heart obstructive lesions such as aortic and mitral stenosis 3.

Considerations for labor and delivery

Patients who are asymptomatic during pregnancy generally tolerate labor and delivery well.

For more severe valvular disease, a high-risk obstetrics team along with a cardiology consultation may be required to manage deliveries.

Antibiotic prophylaxis generally is not recommended for cesarean delivery and is considered optional in women with pulmonic stenosis that is associated with complex congenital heart disease.

Pulmonic stenosis in athletes

Athletes with mild pulmonic stenosis and gradients less than 50 mm Hg have no activity limitations.

Those with more severe pulmonic stenosis can participate in low-intensity competitive sports; their treatment should be directed by the criteria discussed in treatment.

Pulmonic stenosis diagnosis

Physical examination

Visible and palpable signs reflect the effects of right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy and include a prominent jugular venous a wave (due to forceful atrial contraction against a hypertrophied right ventricle), a right ventricle precordial lift or heave, and a left parasternal systolic thrill at the 2nd intercostal space.

Auscultation

- Widened S2 and delayed P2

- Harsh crescendo-decrescendo ejection murmur

On auscultation, the 1st heart sound (S1) is normal and the normal splitting of the 2nd heart sound (S2) is widened because of prolonged pulmonic ejection (P2, the pulmonic component of S2, is delayed). In right ventricle failure and hypertrophy, the 3rd and 4th heart sounds (S3 and S4) are rarely audible at the left parasternal 4th intercostal space. A click in congenital pulmonic stenosis is thought to result from abnormal ventricular wall tension. The click occurs early in systole (very near S1) and is not affected by hemodynamic changes. A harsh crescendo-decrescendo ejection murmur is audible and is heard best at the left parasternal 2nd (valvular stenosis) or 4th (infundibular stenosis) intercostal space with the diaphragm of the stethoscope when the patient leans forward.

Unlike the aortic stenosis murmur, a pulmonic stenosis murmur does not radiate, and the crescendo component lengthens as stenosis progresses. The murmur grows louder immediately with Valsalva release and with inspiration; the patient may need to be standing for this effect to be heard.

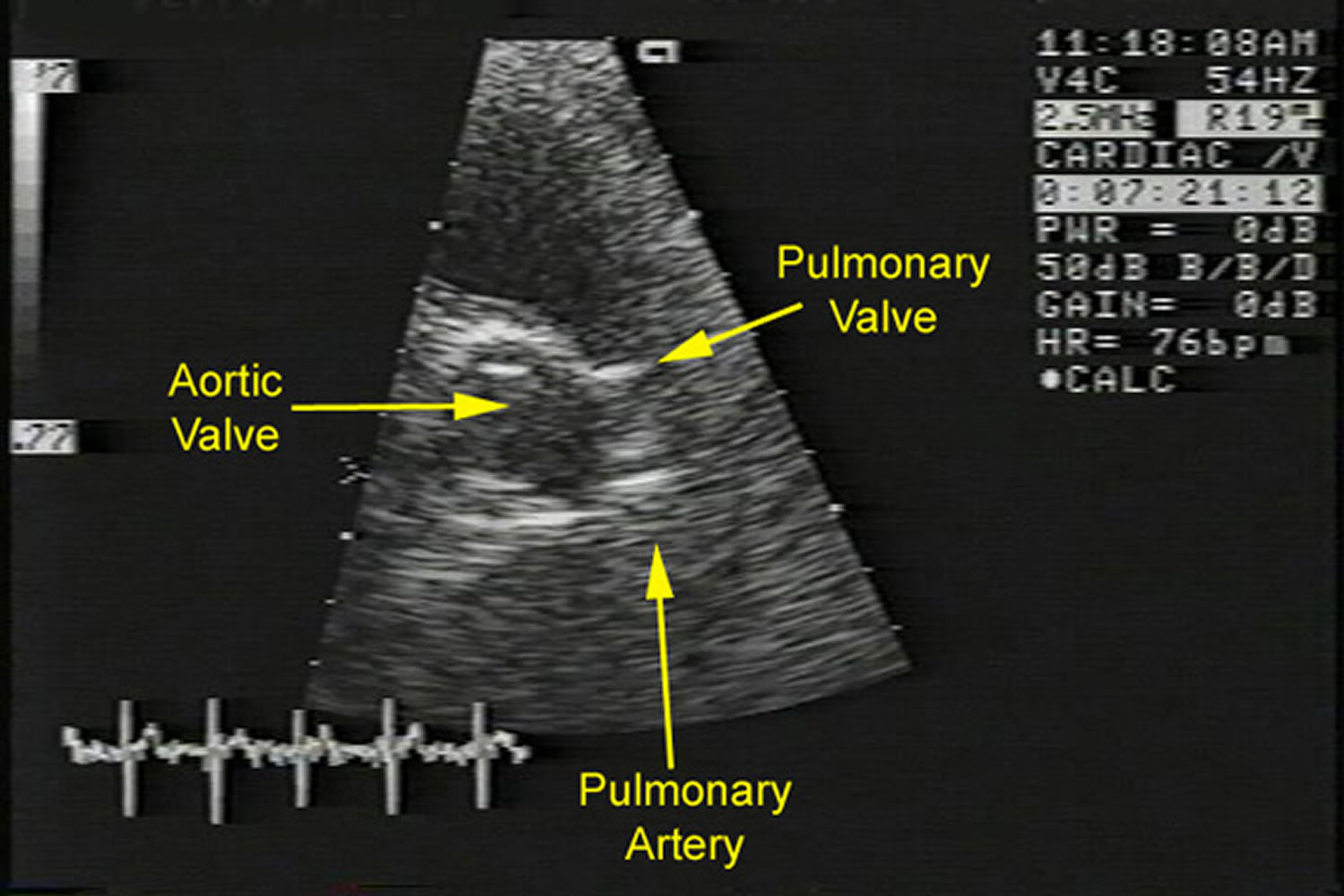

Diagnosis of pulmonic stenosis is confirmed by Doppler echocardiography, which can characterize the severity as:

- Mild: Peak gradient < 36 mm Hg

- Moderate: Peak gradient 36 to 64 mm Hg

- Severe: Peak gradient > 64 mm Hg

Electrocardiography (ECG) may be normal or show right ventricular hypertrophy or right bundle branch block (RBBB).

Right heart catheterization is indicated only when 2 levels of obstruction are suspected (valvular and infundibular), when clinical and echocardiographic findings differ, or before intervention is done.

Figure 1. Pulmonic stenosis echo

Footnote: Echocardiogram of a patient with severe pulmonic stenosis. This image shows a parasternal short axis view of the thickened pulmonary valve.

Pulmonic stenosis treatment

Treatment of pulmonic stenosis is balloon valvuloplasty, indicated for symptomatic patients and asymptomatic patients with normal systolic function and a peak gradient > 40 to 50 mm Hg. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty has become the initial intervention in children, adolescents, and adults with congenital valvar pulmonic stenosis. Balloon valvuloplasty should be considered in any patient with a transvalvular pressure gradient greater than 50 mm Hg 1. Pulmonary artery balloon angioplasty with or without placement of an expandable metal stent can be used to treat supravalvular pulmonic stenosis and peripheral pulmonary stenosis. Expandable metal stents can overcome an obstruction successfully; however, the need for stent reexpansion as the individual grows remains problematic.

Occasionally, balloon valvuloplasty is not successful. These patients tend to have valvular dysplasia (eg, Noonan syndrome) or a hypoplastic pulmonic valve annulus and, therefore, may require surgical valvotomy. Percutaneous valve replacement may be offered at highly selected congenital heart centers, especially for younger patients or those with multiple previous procedures, in order to reduce the number of open heart procedures. When surgical replacement is necessary, bioprosthetic valves are preferred due to the high rates of thrombosis of right-sided mechanical heart valves; anticoagulation is temporarily required.

Infective endocarditis prophylaxis

The American Heart Association Guidelines on Prevention of Bacterial Endocarditis 4 considers all forms of isolated pulmonic stenosis (pulmonic stenosis) to be in the moderate-risk category, and any pulmonic stenosis associated with complex congenital heart disease to be in the high-risk category. Therefore, antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for all forms of pulmonic stenosis.

Pulmonic stenosis prognosis

Prognosis of pulmonic stenosis without treatment is generally good and improves with appropriate intervention.

Except for critical stenosis in neonates, survival is the rule in congenital pulmonic stenosis.

The long-term course of patients with mild pulmonic stenosis is indistinguishable from that of the unaffected population. Mild pulmonic stenosis does not tend to progress in severity; rather, pulmonic valve orifice size usually increases with body growth. However, untreated severe pulmonic stenosis may result in outflow obstruction that progresses over a period of years; 60% of patients with severe pulmonic stenosis require intervention within 10 years of diagnosis.

- Pulmonic Stenosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/157737-overview[↩][↩]

- [Guideline] Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease). Circulation. 2008 Dec 2. 118(23):e714-833[↩]

- Hameed AB, Goodwin TM, Elkayam U. Effect of pulmonary stenosis on pregnancy outcomes–a case-control study. Am Heart J. November 2007. 154:852[↩]

- [Guideline] Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 10. 129(23):e521-643[↩]