Quadriceps strain

A quadriceps muscle strain is an acute tearing injury of the quadriceps muscle group (rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius). The quadriceps is essential for daily activities, such as climbing stairs or getting up from the chair. Acute strain injuries of the quadriceps commonly occur in athletic competitions such as soccer, rugby, and football 1. These sports regularly require sudden forceful eccentric contraction of the quadriceps during regulation of knee flexion and hip extension. Higher forces across the muscle–tendon units with eccentric contraction can lead to strain injury. Excessive passive stretching or activation of a maximally stretched muscle can also cause strains. Of the quadriceps muscles, the rectus femoris is most frequently strained 2. Several factors predispose the quadriceps muscle and others to more frequent strain injury. These include muscles crossing two joints, those with a high percentage of type 2 fibers, and muscles with complex musculotendinous architecture 3. Muscle fatigue has also been shown to play a role in acute muscle injury 4.

Quadriceps strains key points 5

- The highest rates of quadriceps strains were found in women’s and men’s soccer.

- Rates of quadriceps strains were higher in women versus men (in sex-comparable sports), in competitions versus practices, and in the preseason versus regular season.

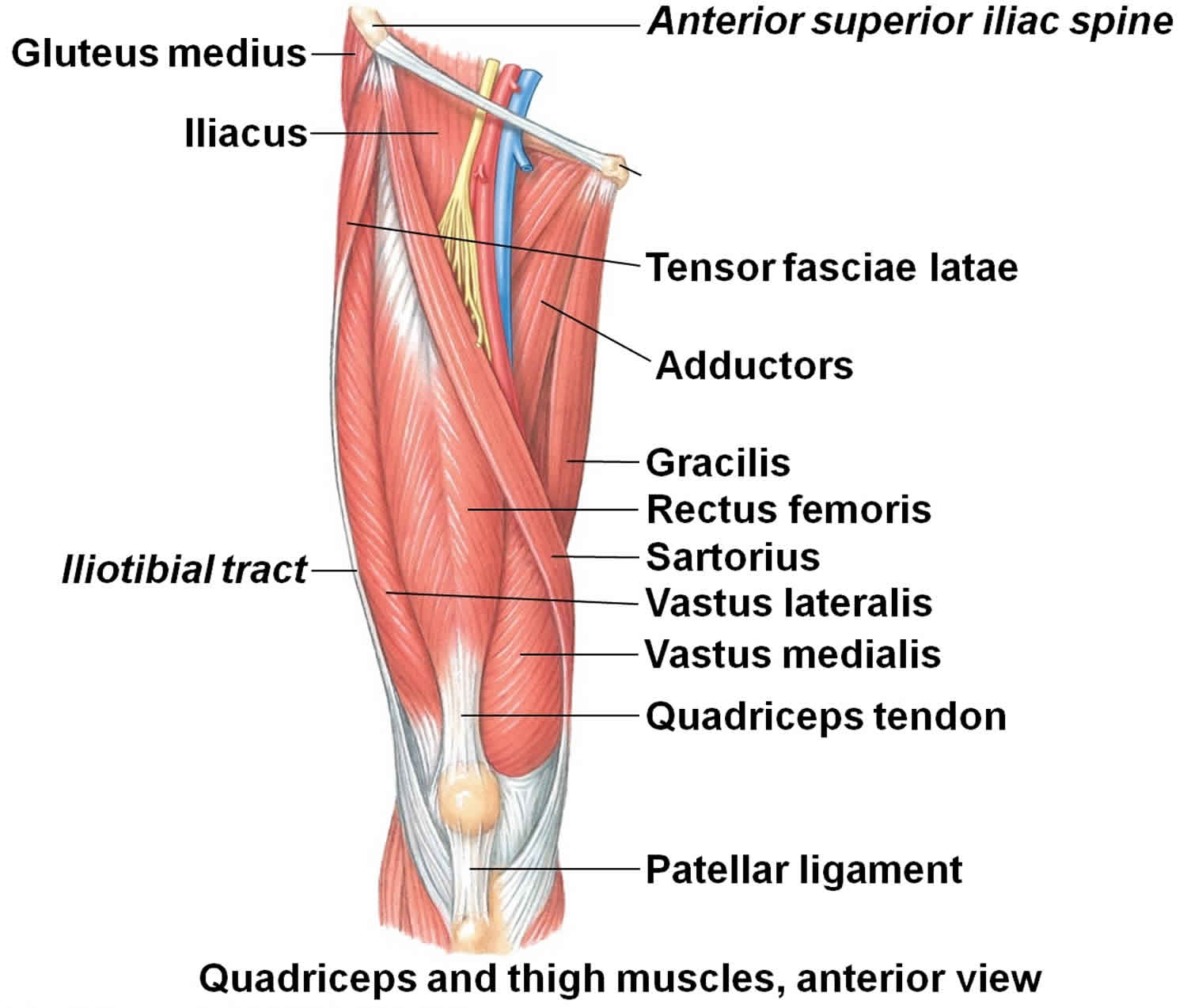

Quadriceps anatomy

The quadriceps muscle group is composed of the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius. The rectus femoris originates at the ilium, thus crossing both the hip and knee joint along its course. The rectus femoris is the only part of the quadriceps muscle group participating in both flexion of the hip and extension of the knee. The remaining muscles originate on the femur and function solely as knee extensors. The quadriceps tendon attaches the quadriceps muscles to the patella. The patella is attached to the shinbone (tibia) by the patellar tendon. Working together, the quadriceps muscles, quadriceps tendon and patellar tendon straighten the knee. Innervation of the quadriceps muscle group is by the femoral nerve. The quadriceps are primarily active in kicking, jumping, and running.

- Rectus femoris originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine with the direct tendon, and the upper rim of the acetabulum with the indirect tendon. With a third and small tendon (reflected tendon), it attaches to the hip joint capsule anteriorly. The first 2 rectus femoris tendons continue downward with two aponeurotic laminae, up to two-thirds of the rectus femoris. The direct tendon will become the superficial lamina while the indirect tendon continues as a central sagittal lamina.

- Vastus lateralis originates from the lateral face of the great trochanter, from the gluteal tuberosity and the lateral lip of the linea aspera.

- Vastus medialis originates from the anatomical neck of the femur and the medial lip of the linea aspera. The vastus medialis is deeply inserted in the aponeurosis of the vastus intermedius, while the tensor of the vastus intermedius is inserted in the same aponeurosis, more superficial.

- Vastus intermedius originates from the proximal three-fourths of the anterior and lateral faces of the femoral body, and from the lateral lip of the linea aspera. Some bundles of the vastus intermedius are inserted in the upper recess of the supra-patellar bursae, making up the articular muscle of the knee.

- Recently, another muscle, the tensor of the vastus intermedius, has been identified as part of the quadriceps femoris. The tensor of the vastus intermedius starts from the anteroinferior portion of the great trochanter. It joins with a wide flat aponeurosis between vastus lateralis and vastus intermedius in the central area of the thigh, and they join with a single tendon in the upper part of the patella, merging into the quadriceps tendon. At the dorsal level of the thigh, the muscle fibers of these 3 muscles merge in the vicinity of the linea aspera of the femur. At the level of the great trochanter, this muscle also can originate from the gluteus minimus.

The following are the functions of the quadriceps muscle 6:

- Knee extension

- Hip flexion

- Maintenance of posture

- Proper stage of step/gait cycle

- Maintenance of patellar stability

The rectus femoris is the most superficial part of the quadriceps and it crosses both the hip and knee joints, thus also making it more susceptible to stretch-induced strain injuries 7. The most common sites of strains are the muscle tendon junction just above the knee (both distal and proximal but most frequently at the distal muscle-tendon) and in the muscle itself.

Figure 1. Quadriceps muscle group

Quadriceps injury causes

The quadriceps muscle group, made up of 4 muscles in the anterior thigh, is at particular risk for strains in events that involve explosive movements and require forceful eccentric contractions to decelerate knee-flexion and hip-extension motions, such as kicking, jumping, or a sudden change in direction while running 1. A quadriceps tear often occurs when there is a heavy load on the leg with the foot planted and the knee partially bent. Jumps are a high-risk activity for quadriceps strains due to the significant eccentric work that the quadriceps must perform to counter first, hip-extension moments that occur during upward propulsion, and second, knee-flexion moments during the absorption phases of jump landings 8. Jump-landing training that focuses on decreasing the activation ratio of the quadriceps to the hamstrings is already recommended to decrease the risk of injuries such as noncontact anterior cruciate ligament ruptures during jumping tasks, and it has the potential to decrease the risk of quadriceps strains as well 9. Sprinting also requires the quadriceps to perform significant eccentric work, making them vulnerable to injury.

The rectus femoris is the most commonly strained quadriceps muscle, likely due to the fact that it is the sole biarticular muscle in the group, capable of both knee extension and hip flexion 10. This role requires the rectus femoris to provide forceful eccentric contractions across both the hip and knee during rapid deceleration movements, increasing its vulnerability to strain 10.

To reduce the likelihood of injury during both sprinting and jumping, athletes should strengthen their quadriceps through resistance training that emphasizes eccentric work, which has been demonstrated to decrease the incidence of hamstrings strains 11.

Risk factors for quadriceps strains

The following are risk factors for quad strains:

- Not warming up correctly: If you do not warm up the quadriceps muscles prior to playing sports which involve large knee or hip movements, there is an increased risk of suffering a thigh strain. Prior to exercise, a sport specific warm up should be performed including gentle stretching, sub-maximal cardio workout and range of motion exercises.

- Previous injury: A thigh strain that has either not fully healed or left residual scar tissue may predispose to a further thigh strain in the future

- Sports activities which hold a risk of thigh strains include football, soccer, rugby, basketball, and long distance running or sprinting.

Quadriceps strains classification

Various ways of grading muscle strains have been proposed 3. Factoring in pain, loss of strength, and physical exam findings in a grading system helps provide guidance for treatment, rehabilitation, and eventual return to play 1.

- Grade 1 strains represent minor tearing of muscle fibers with only minimal or no loss in strength. Pain is usually mild to moderate with no palpable defect in the muscle tissue when examined by a doctor.

- Grade 2 strains involve more severe disruption to the muscle fibers with significant pain and loss of strength. A defect in the muscle tissue may sometimes be felt by your doctor.

- Grade 3 strains are a result of complete tearing of the muscle with associated severe pain and complete loss of strength. A palpable defect in the muscle tissue can frequently be felt, especially if examined at onset of injury prior to hematoma formation.

Recovery is longer with a high-grade injury, and the long-term outcome is potentially worse.

Table 1 provides an outline of a clinical grading system for quadriceps muscle strains.

Table 1. Clinical grading system for quadriceps strains

| Grade | Pain | Strength | Physical exam |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mild | None or minimal loss of strength | No palpable muscle defect |

| 2 | Moderate | Moderate loss of strength | May feel a small palpable muscle defect |

| 3 | Severe | Usually complete loss of strength | Often feel a palpable muscle defect |

Quadriceps strains prevention

Prevention of quad strains requires a focus on good flexibility and strength of the thigh muscles. By following a few simple rules, the likelihood of thigh strains can be reduced:

- Warm up: A warm up should be performed prior to sport which should involve some simple sport specific drills and range of motion exercises (eg. leg swings, jogging, jumping, direction changes whilst jogging, if playing soccer or football)

- Strengthening: Make sure the muscles of the thigh are well conditioned through strengthening programs

Quadriceps injury symptoms

The following are general symptoms of quadriceps strains:

- At the time of injury, a popping or tearing sensation may be felt as the muscle is strained.

- Pain: Frequently a sharp pain is felt in the front of the thigh at the time of injury. Sometimes pain will not fully develop until the end of a game, practice, or sporting activity. Location of pain can be anywhere along the quadriceps muscle, (which runs along the front of the thigh), but is classically felt nearer the knee than the hip.

- Weakness: The strained muscle may feel weak. This can lead to a sensation of loosing power in the leg.

- Swelling: There may be swelling over the site of the thigh strain. Bruising may also be present.

Grade 1 symptoms

Symptoms of a grade 1 quadriceps strain are not always serious enough to stop training at the time of injury. A twinge may be felt in the thigh and a general feeling of tightness.The athlete may feel mild discomfort on walking and running might be difficult.There is unlikely to be swelling. A lump or area of spasm at the site of injury may be felt.

Grade 2 symptoms

The athlete may feel a sudden sharp pain when running, jumping or kicking and be unable to play on.Pain will make walking difficult and swelling or mild bruising may be noticed.The pain would be felt when pressing in on the suspected location of the quad muscle tear.Straightening the knee against resistance is likely to cause pain and the injured athlete will be unable to fully bend the knee.

Grade 3 symptoms

Symptoms consist of a severe,sudden pain in the front of the thigh.The patient will be unable to walk without the aid of crutches.Bad swelling will appear immediately and significant bruising within 24 hours. A static muscle contraction will be painful and is likely to produce a bulge in the muscle. The patient can expect to be out of competition for 6 to 12 weeks.

Quadriceps strains complications

If a quad strain is not properly treated, or a return to sport is made before the injury has enough time to recover, the thigh strain can become chronic. This means that there is ongoing pain in the thigh area requiring prolonged rehabilitation.

Quadriceps strains may leave the affected muscle slightly weaker or slightly tighter than prior to the injury. This can predispose to straining the same area again in the future. It is important to complete the full course of treatment and rehabilitation laid out by your doctor or physiotherapist in order to minimize this risk.

Symptomatic fibrosis (or scarring) occurs less frequently. In some athletes, how-ever, a severe muscle strain injury will result in a painful area of scarring or fibrosis. Treatment for this complication should involve physical therapy with stretching and perhaps the use of modalities such as ultrasound and deep-tissue massage. Very occasionally, surgical intervention is required to remove the area of scar tissue.

Quadriceps injury diagnosis

Quadriceps strains are initially diagnosed through a thorough history and examination. An accurate history should be obtained in patients presenting with anterior thigh pain. Patients who suffer an acute quadriceps strain will usually know right away. They are typically involved in kicking, jumping, or initiating a sudden change in direction while running. Frequently a sharp pain is felt associated with a loss in function of the quadriceps. Sometimes pain would not fully develop until the end of a game, practice, or sporting activity. Pain may be associated with localized swelling and loss of motion. Location of pain can be anywhere along the quadriceps muscles, but is classically described along the distal portion of the rectus femoris at the musculotendinous junction. However, several studies have shown quadriceps strains commonly occur at the mid to proximal portion of the rectus femoris 2.

Physical examination

After obtaining a thorough history, a careful examination should ensue including observation, palpation, strength testing, and evaluation of motion. Strain injuries of the quadriceps may present with an obvious deformity such as a bulge or defect in the muscle belly. Ecchymosis may not develop until 24 hour after the injury. Palpation of the anterior thigh should include the length of the injured muscle, locating the area of maximal tenderness and feeling for any defect in the muscle. Strength testing of the quadriceps should include resistance of knee extension and hip flexion. Adequate strength testing of the rectus femoris must include resisted knee extension with the hip flexed and extended. Practically, this is best accomplished by evaluating the patient in both a sitting and prone-lying position. The prone-lying position also allows for optimum assessment of quadriceps motion and flexibility. Pain is typically felt by the patient with resisted muscle activation, passive stretching, and direct palpation over the muscle strain. Assessing tenderness, any palpable defect, and strength at the onset of muscle injury will determine grading of the injury and provide direction for further diagnostic testing and treatment.

Imaging studies

Most acute injuries to the quadriceps musculature can be diagnosed with an adequate history from the patient and a thorough examination. Imaging can be a useful adjunct in those cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or further detail is needed regarding the type and location of the muscle strain. Radiographs, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the commonly used imaging tools for this area. Radiographs are routinely normal in acute muscle strains, but may be helpful in differentiating between bony (femoral stress fracture, tumor, or myositis ossificans) and muscular etiologies of quadriceps pain in chronic cases. Ultrasound is an excellent imaging modality for visualizing the quadriceps muscles and tendons, but is highly operator dependent and requires a skilled and experienced clinician 3. Ultrasound has the ability to image the muscles dynamically and assess for bleeding and hematoma formation via Doppler. MRI provides detailed images of muscle injury and can be quite helpful in characterizing quadriceps injuries 12. It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between muscular contusion and strain on MRI, which simply re-enforces the importance of clinical history and examination in injury assessment 12. Prognostically, Cross et al. found strains of the central tendon of the rectus femoris, identified on MRI, correlated with a significantly longer rehabilitation period 2.

Quadriceps strain treatment

Quadriceps strains generally recover well. The goals of treatment are to minimise the pain, allow the muscle to heal and then restore normal range of motion and strength. This treatment follows a stepwise process. Treatment of muscle strain injuries has not changed greatly over the years and there is little scientific basis for the majority of treatment protocols 1. Despite the relative paucity of literature specific to treatment of muscle injuries, there are certain principles which provide a basis for the currently accepted methods of treatment. When muscle is acutely damaged by strain, contusion, or laceration, there is bleeding and hematoma formation among the ruptured muscles cells followed by an inflammatory reaction 3.

Initial treatment – rest and recovery

The first 24–72 hours after a quadriceps strain should be focused on the ‘RICE’ principles: rest, ice, compression and elevation. Your doctor may also prescribe some anti-inflammatory medication or pain relief medication. The use of crutches when walking may be necessary to protect the thigh muscles from further damage and to hasten the healing process. If the thigh strain is minor, this may be all the treatment that is required.

Acute phase treatment of quadriceps strains is focused on minimizing bleeding into the muscles by following the RICE principle (rest, ice, compression, and elevation). Allowing the muscle to rest prevents worsening of the initial injury. Ice or cold application is thought to lower intra-muscular temperature and decrease blood flow to the injured area. This may help facilitate faster healing and return to athletics, but has not been proven in the scientific literature 13. This same review did show that cryotherapy is effective in decreasing pain associated with muscle injury 13. Compression may help decrease blood flow and accompanied by elevation will serve to decrease both blood flow and excess interstitial fluid accumulation. Practically, the first 24–72 hours after quadriceps strain should be focused on the RICE principles. Cryotherapy, accompanied by compression, should be applied for 15–20 minutes at a time with 30–60 minutes between applications. During this time period, the quadriceps should be kept relatively immobile to allow for appropriate healing and prevent further injury 3. A grade 2 or 3 strain may necessitate the use of crutches initially to facilitate rest and immobilization of the quadriceps. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be useful for reducing pain and allowing earlier return to activity. The long-term effects of NSAIDs in muscle strains are unknown and a recent review recommends only a short 3–7 day course after muscle strains 14. In contrast, the use of corticosteroids is definitely discouraged based on research demonstrating delayed healing and reduced biomechanical strength of injured muscle 15.

Rehabilitation – passive and active range of motion exercises

The acute phase of treatment is subsequently followed by an active phase of management once the injured leg is recovering well. This phase usually begins approximately 3–5 days after the initial injury depending on its severity. A graduated flexibility and strengthening program guided by a physiotherapist may be necessary for more severe thigh strains. Careful assessment by the physiotherapist to determine which factors have contributed to the development of the condition, with subsequent correction of these factors is also important to ensure an optimal outcome. The rehabilitation will involve moving the knee, first passively and then actively. This means initially, the knee is moved either by someone else or using your arms to assist the movement such that the injured muscle does not work during these movements. Following this knee and hip movements are performed using the muscles that have been injured.

Stretching, strengthening, range of motion, maintenance of aerobic fitness, proprioceptive exercises, and functional training are the primary components of this phase. Stretching should be done carefully and always to the point of discomfort, but not pain. Various techniques can be utilized including passive, active–passive, dynamic, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching. Generally, ballistic stretching is discouraged due to the risk of re-tearing muscle fibers. An active warm-up should always precede any type of rehabilitation exercises as it has been shown to activate neural pathways in the muscle and reduce muscle viscosity 3.

Final stages – strength training

Strengthening exercises can begin gradually and should progress sequentially through isometric, isotonic, isokinetic, and functional exercises.

Initially exercises will be given that isolate and strengthen the injured muscle. Once the muscle regains its strength, a graduated return to running or sport specific activities is the final stage of rehabilitation and is required to fully recondition the thigh muscles. This should include the implementation of progressive acceleration and deceleration running drills before returning to sport.

Once there is full range of motion of the hip and knee, full strength equal or greater than the uninjured thigh, and you are able perform all of the fundamental skills of the required sport pain free, you are ready to return to sport.

Table 2 provides definitions of these various strengthening techniques.

Table 2. Strengthening techniques

| Isometric | Muscle contraction against a fixed object resulting in no change in muscle length |

| Isotonic | Muscle contraction against a constant resistance, with uncontrolled speed of movement, resulting in muscle shortening or lengthening through a range of motion |

| Isokinetic | Muscle contraction through a range of motion at a constant angular velocity |

| Functional | Sport or activity specific strengthening exercises such as sprinting, jumping, or agility drills |

All strengthening exercises should be performed through a pain-free range of motion. Advancement through each type of strengthening depends on the level of soreness and pain created by each type of exercise. For example, once isometric straight leg raises at 0°, 20°, and 40° can be completed without any pain or subsequent soreness, isotonics can then be initiated. Maintaining aerobic fitness during rehabilitation is important and can be accomplished by using activities like swimming and biking. Once again, these activities should not increase pain in the injured quadriceps and should be performed in a pain-free range of motion.

Return to sports

Consideration of return to sports criteria is important when managing quadriceps strains in athletic patients. There are no established consensus guidelines or criteria for safe return to sports following muscle strains 16. Practically, athletes should have normal knee range of motion, be pain free, demonstrate near normal strength compared to the contralateral side and perform well on functional field tests 17. Isokinetic muscle strength testing can be a useful tool for assessing strength and guiding return to sports.

- Kary JM. Diagnosis and management of quadriceps strains and contusions. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2010;3(1-4):26–31. Published 2010 Jul 30. doi:10.1007/s12178-010-9064-5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2941577[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Cross TM, Gibbs N, Houang MT, et al. Acute quadriceps muscle strains: magnetic resonance imaging features and prognosis. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:710–719. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261734[↩][↩][↩]

- Järvinen TAH, Järvinen TLN, Kääriäinen M, et al. Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:745–764. doi: 10.1177/0363546505274714[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Mair SD, Seaber AV, Glisson RR, et al. The role of fatigue in susceptibility to acute muscle strain injury. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:137–143. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400203[↩]

- Eckard TG, Kerr ZY, Padua DA, Djoko A, Dompier TP. Epidemiology of Quadriceps Strains in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes, 2009-2010 Through 2014-2015. J Athl Train. 2017;52(5):474–481. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-52.2.17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5455251[↩]

- Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Thigh Quadriceps Muscle. [Updated 2018 Dec 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513334[↩]

- Almekinders LC. Anti-inflammatory treatment of muscular injuries in sport. An update of recent studies. Sports Med. Dec 1999;28(6):383-8.[↩]

- Lower extremity muscle activation and knee flexion during a jump-landing task. Walsh M, Boling MC, McGrath M, Blackburn JT, Padua DA. J Athl Train. 2012 Jul-Aug; 47(4):406-13.[↩]

- Zebis MK, Bencke J, Andersen LL, et al. The effects of neuromuscular training on knee joint motor control during sidecutting in female elite soccer and handball players. Clin J Sport Med. 2008; 18 4: 329– 337.[↩]

- An explanation for various rectus femoris strain injuries using previously undescribed muscle architecture. Hasselman CT, Best TM, Hughes C 4th, Martinez S, Garrett WE Jr. Am J Sports Med. 1995 Jul-Aug; 23(4):493-9.[↩][↩]

- Arnason A, Andersen TE, Holme I, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2008; 18 1: 40– 48.[↩]

- Bencardino JT, Rosenberg ZS, Brown RR, et al. Traumatic musculotendinous injuries of the knee: diagnosis with MR imaging. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:S103–S120.[↩][↩]

- Bleakley C, McDonough S, MacAuley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft-tissue injury: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sport Med. 2004;32:251–261. doi: 10.1177/0363546503260757[↩][↩]

- Mehallo CJ, Drezner JA, Bytomski JR. Practical management: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in athletic injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:170–174. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200603000-00015[↩]

- Beiner JM, Jokl P. Muscle contusion injury and myositis ossificans traumatica. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;403S:S110–S119. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200210001-00013[↩]

- Orchard J, Best TM, Verrall GM. Return to play following muscle strains. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:436–441. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000188206.54984.65[↩]

- DeLee JC, Drez D, Miller MD. Orthopaedic sports medicine: principles and practice. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003.[↩]