Radioulnar synostosis

Radioulnar synostosis can take two general forms: congenital radioulnar synostosis and posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis. Each form may be further classified into types. Congenital radioulnar synostosis is a rare condition in which there is an abnormal connection (synostosis) of the radius and ulna (bones in the forearm) at birth 1. Congenital radioulnar synostosis occurs rarely, with approximately 350 cases reported in the literature. The rarity of this condition often leads to a delayed clinical diagnosis. Congenital radioulnar synostosis is present in both arms (bilateral) in approximately 60–80% of cases 2. Signs and symptoms depend on the severity of the abnormality and whether it is bilateral; people with congenital radioulnar synostosis often have limited rotational movement of the movements of the forearm, which may lead to difficulties with some activities of daily living 3. Pain is usually not present until the teenage years 4.

Normally, the ulna bone acts as a straight “post” to anchor the wrist to the elbow. The radius bone rotates around the ulna to allow the forearm to turn palm up and palm down. This rotation is helpful for daily activities and allows many actitivies such as typing on the keyboard (palm down or “pronation”) or hold change (palm up or “supination”). Almost all rotation comes through the forearm (ie the relationship between radius and ulna) but some can come through the wrist bones also.

Some children with congenital radioulnar synostosis adapt amazingly well to the radioulnar synostosis. Often, families do not even realize this condition is present until after kids start school. There is no pain and some rotation can be achieved through the wrist. When both sides are affected, it may be a little more challenging to adapt. Additionally, it matters in which position the forearm is fused. The forearm can be “stuck” in full palm up (supination), full palm down (pronation), or anywhere in between. The best position is half- way between (the clapping position) which allows the patient to use the shoulder to help accommodate in both directions. Palm down is better than palm up as so many of life’s activities are palm down (keyboarding, etc).

In a small number of kids, the forearm position causes trouble with activities. In those, a small surgery can be done to reposition the forearm in a better position for function.

There are 2 types of congenital radioulnar synostosis: type 1 and type 2. In type 1 congenital radioulnar synostosis, the fusion involves 2-6 cm of the area between the radius and ulna bones which is closer to the elbow and the knobby end of the radius that meets the elbow is absent (radial head). In type 2 congenital radioulnar synostosis, the fusion is farther from the elbow and there is dislocation of the radial head. Both types result in a limitation of inward roll (pronation) and outward roll (supination) of the forearm, and in type 2 there is also a restriction of extension at the elbow 5. Congenital radioulnar synostosis is due to abnormal fetal development of the forearm bones, but the underlying cause is not always known. Radioulnar synostosis is sometimes a feature of certain chromosome abnormalities or genetic syndromes 1. Some cases appear to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner 5. Treatment may be conservative or involve surgery depending on the severity of the abnormality and the range of motion 4.

Posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis is a separate entity from the congenital radioulnar synostosis, having a different cause, treatment, and prognosis 6. The traumatic form can occur anywhere between the radius and ulna along the length of the interosseous membrane.

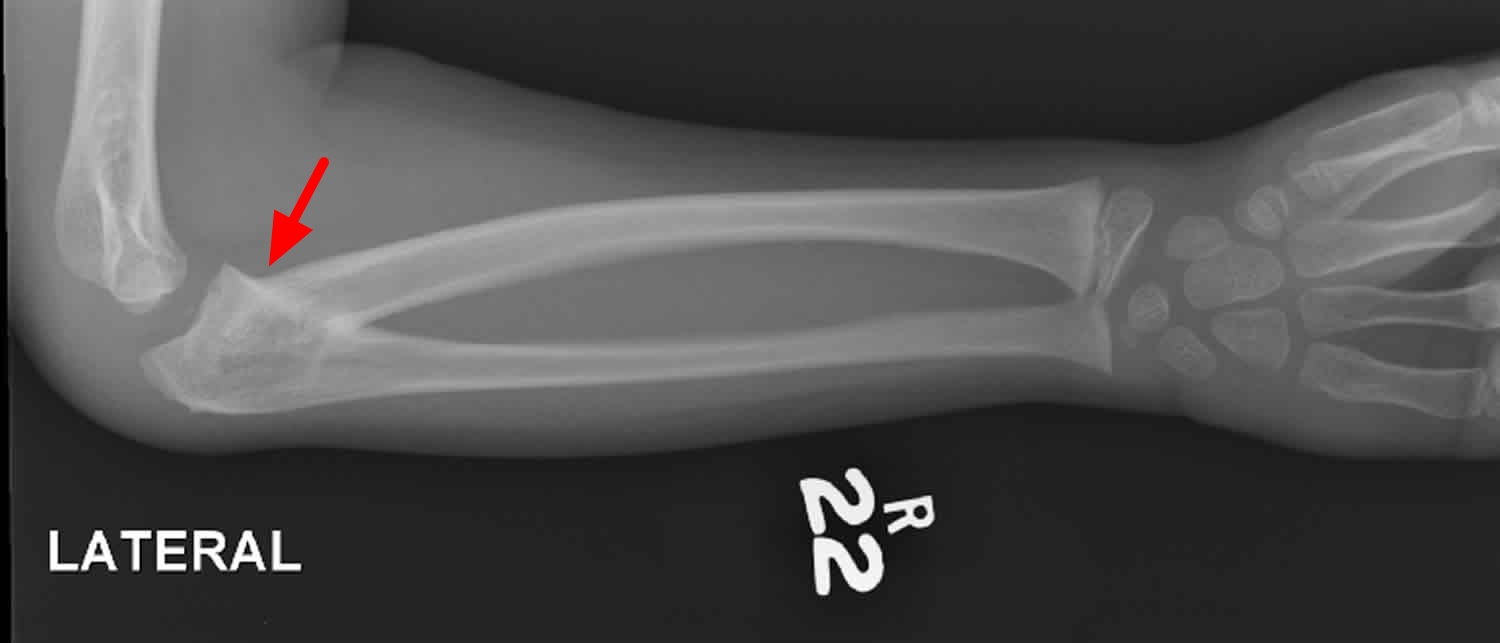

Figure 1. Radioulnar synostosis X-ray showing synostosis near elbow. The two bones are joined together.

Radioulnar synostosis causes

Congenital radioulnar synostosis is caused by abnormal development of the forearm bones during the fetal period, although the underlying cause of the developmental abnormality is not always known. Congenital radioulnar synostosis may be isolated (occur without other abnormalities) or it may be associated with various other skeletal, heart (cardiac), neurologic, or gastrointestinal abnormalities. When other abnormalities are present, congenital radioulnar synostosis may be due to an underlying genetic cause, including a variety of syndromes or chromosome abnormalities 4. Some chromosome abnormalities that may include radioulnar synostosis are Klinefelter syndrome and XXXY syndrome. Examples of genetic syndromes that may include radioulnar synostosis are Apert syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, Carpenter syndrome, arthrogryposis, Treacher Collins syndrome, Williams syndrome, amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia, and Holt-Oram syndrome 7.

The most common cause of posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis is an operatively treated forearm fracture 8. Patients with high-energy comminuted open fractures appear to be more likely to develop this complication. Monteggia and proximal forearm fractures also appear to have a higher incidence of synostosis 9. The use of bone graft and of screws protruding through the opposite cortex also increase the incidence of synostosis.

Additionally, radioulnar synostosis is described as a consequence of soft-tissue injury, reconstructive procedures, any trauma causing hematoma formation between the radius and ulna, or injury to the interosseous membrane 10. Patients with closed head injuries (skull/cranial trauma) appear to be more prone to this complication, presumably for the same reason that they develop heterotopic ossification 11.

Congenital radioulnar synostosis inheritance pattern

Congenital radioulnar synostosis appears to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner in some cases 5. In 20% of their patients, Cleary and Omer found a genetic basis for an autosomal dominant form (with variable penetrance) of congenital radioulnar synostosis 12. This means that one mutated copy of the disease-causing gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition. The mutated gene may occur for the first time in an affected individual, or it may be inherited from an affected parent. Each child of an individual with an autosomal dominant condition has a 50% (1 in 2) risk to inherit the mutated copy of the gene.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

Congenital radioulnar synostosis may also occur with a variety of other abnormalities and may be associated with a chromosome abnormality or with a genetic syndrome. In these cases, the inheritance pattern may depend upon that of the underlying genetic abnormality 4.

Congenital radioulnar synostosis may also occur sporadically as an isolated abnormality, in which case the cause may be unknown.

Figure 2. Congenital radioulnar synostosis autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Radioulnar synostosis symptoms

Congenital radioulnar synostosis symptoms

Wilkie divided congenital radioulnar synostosis into the following two types on the basis of the proximal radioulnar junction 13:

- Type 1 – Complete synostosis has occurred, with the radius and ulna fused proximally for a variable distance

- Type 2 – Less involved, and may exist as a partial union; this type involves the region just distal to the proximal radial epiphysis and is associated with radial head dislocation

Cleary and Omer described four types of congenital radioulnar synostosis, as follows 12:

- Fibrous synostosis

- Bony synostosis

- Associated posterior dislocation of the radius

- Associated anterior dislocation of the radius

Simmons et al considered congenital radioulnar synostosis to be a spectrum of anomalies in which the synostosis occurred in varying lengths, with or without involvement of the radial head 14.

Because congenital radioulnar synostosis is caused by an in-utero insult, its association with other abnormalities is not surprising. About one third of cases are associated with general skeletal abnormalities, such as hip dislocation, knee anomalies, clubfoot, polydactyly, syndactyly, Madelung deformity, ligamentous laxity, thumb hypoplasia, carpal coalition, and problems of the cardiac, renal, neurologic, and gastrointestinal systems.

Some associated abnormalities and syndromes are genetically determined, including acrocephalosyndactyly, Apert syndrome, Carpenter syndrome, arthrogryposis, mandibulofacial dysostosis, William syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Holt-Oram syndrome, microcephaly, multiple exostoses, and fetal alcohol syndrome 15.

Functional deficits associated with congenital radioulnar synostosis depend on the severity of the deformity and on whether or not it is bilateral. In cases involving severe, fixed forearm pronation deformity, the patient cannot compensate for the resulting functional limitations by using scapular and glenohumeral motion. The forearm usually lies in the pronated or hyperpronated position.

Hypermobility at the midcarpal and radiocarpal joints can disguise this lack of forearm rotation, particularly with neutral or mild pronation deformities. There is usually full or nearly full elbow range of motion, with flexion contractures rarely exceeding 30º. An abnormal carrying angle of the elbow or a shortening of the forearm may be observed.

Pain is usually not a presenting symptom until the teenage years, when progressive and symptomatic radial head subluxation may be noted. This accounts for the delayed clinical diagnosis in many cases, but it also indicates that function may be satisfactory. The disability is most significant in bilateral cases with severe pronation. Children may initially have a reduced radial head and in adolescence may develop symptomatic radial head subluxation. Therefore, radiographic follow-up is necessary.

Posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis symptoms

Posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis has been classified into the following three types on the basis of location:

- Type 1 – Least common; occurs in the distal forearm

- Type 2 – Occurs in the midforearm

- Type 3 – Occurs in the proximal forearm

Radioulnar synostosis diagnosis

Plain radiographic imaging in orthogonal (eg, posteroanterior [PA] and lateral) planes is recommended for the workup of patients with congenital radioulnar synostosis or posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis.

Radioulnar synostosis treatment

Congenital radioulnar synostosis may be treated with surgery. Surgery is more commonly performed in patients who have bilateral radioulnar synostosis and/or patients who have very limited movement due to the radioulnar synostosis. In some cases, surgery is best performed in early childhood, usually before school starts, and in some cases it may need to be done in several stages. Surgery is not generally recommended for older patients with milder deformities who have learned to compensate for the limited range of movement caused by the synostosis, by using their shoulders and/or wrists. Complications of the surgery may include nerve damage or recurrence of the fusion 4. The only contraindication for surgical correction is the presence of milder deformity in an older patient, if the patient has only minimal functional deficit and has already made adjustments in his/her activities to accommodate the radioulnar synostosis.

The indication for surgery in posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis is functional limitation of forearm rotation. This limitation must be assessed on an individual basis. An appropriate workup includes taking plain radiographs in orthogonal (eg, posteroanterior and lateral) planes.

Surgery should be performed after the synostosis has matured and distinct radiographic borders are observed, so as to decrease the likelihood that the synostosis will recur. Waiting more than 3 years, however, adversely affects final outcome, probably because of soft-tissue contracture. A 100º arc of motion is desired so that the patient can perform all activities of daily living (ADLs), and a 60º arc is required to perform most activities of daily living without assistance.

Surgical treatment

Attempts to achieve and maintain motion at the synostosis site usually are not successful. Synostosis typically recurs despite excision, the use of various medications, or the interposition of silicone, fat, or muscle. However, success has been reported with excision of the bony bridge and the interposition of vascularized fat graft, with an average rotation range of 74º being maintained at 2 years after surgery 16.

Some mobilization procedures are combined with tendon transfers to achieve supination. The flexor carpi ulnaris can be transferred dorsally around the ulna, and the extensor carpi radialis longus can be transferred to the volar aspect of the wrist. Overall, the preferred surgical procedure has been osteotomy and derotation through the fusion mass, along with fixation with transcutaneous pins 17.

The optimal position of correction varies according to the degree of involvement, the bilaterality of the synostosis, and the amount of compensatory shoulder or radiocarpal motion that the patient has. Severe deformities do not allow one-stage correction, because of the tension on vascular and fibrous structures. Gradual correction using a multiplanar external fixator decreases the risk of neurovascular compromise and allows the patient to select the most functional position.

Reports of the optimal correction position vary. In general, neutral rotation is used for unilateral deformities; for bilateral deformities, one side is placed in 20-30º of pronation and the other in 20-30º of supination 18. Shortening of the forearm to decrease the risk of neurovascular compromise has also been recommended.

A long arm cast with 90º of elbow flexion is utilized postoperatively for 8 weeks. Transcutaneous pins are recommended for fixation after derotation. Unlike techniques that require open operative exposure, this pinning can easily be reversed if postoperative vascular compromise develops 19.

Simcock et al 20 described the use of derotational osteotomy to treat 31 forearms in 26 children with congenital radioulnar synostosis and functional limitations. In all cases, union was successfully achieved by 8 weeks. No instances of compartment syndrome, vascular compromise, or loss of fixation occurred. The overall rate of complications was 12%, including two transient anterior interosseous nerve palsies (both in patients with rotational corrections >80º), one transient radial nerve palsy, and one symptomatic muscle herniation.

Hwang et al 21 studied the use of one-stage rotational osteotomy of the proximal third of the ulna and distal third of the radius with segmental bone resection to treat congenital radioulnar synostosis in 25 patients (28 forearms). In group 1, the ulnar osteotomy was stabilized with an intramedullary pin, whereas in group 2, no fixation was used. Surgical outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups. The authors concluded that one-stage rotational osteotomy of the proximal third of the ulna and distal third of the radius with segmental bone resection is simple and safe in this setting and that internal fixation at the osteotomy site seems to be unnecessary.

Bishay 22 prospectively studied 12 consecutive pediatric patients (14 forearms) with severe congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis (mean pronation deformity, 70.7°; range, 60-85°) that was corrected by menas of single-session double-level rotational osteotomy and percutaneous placement of intramedullary Kirschner wires (K-wires) in both radius and ulna. After a mean interval of 30.4 months (range, 24-36 months), patients had a mean pronation deformity correction of 59.8°. All 12 patients showed improvement in functional activities; none had any loss of correction or nonunion, circulatory disturbances, neuropathies, or hypertrophic scars.

Satake et al 23 studied the long-term (≥10 years) results of simple rotational osteotomy for congenital radioulnar synostosis in nine patients (12 forearms). After the procedure, the forearm was fixed at an average of 4.2° of supination. At final follow-up, the average motion arc of the palm ranged from 26° of pronation to 62° of supination. No postoperative neurologic or circulatory complications were noted. Patients were much better able to perform ADLs, and all were satisfied with the results of surgery. The average score on the 11-item version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score was 3.79 points at final follow-up.

In contrast to surgery for congenital radioulnar synostosis, surgery for the posttraumatic form of the condition restores motion through excision of the synostosis area 24. Numerous interposition materials—including fat, muscle, fascia, silicone, and cellophane—have been proposed for use after resection to prevent a recurrence of synostosis, but these have met with varying degrees of success. Kelikian and Doumanian 25 developed a metallic swivel prosthesis to restore motion, but no large series has been reported that supports its effectiveness.

The goal of treatment, regardless of what interpositional material is used, involves resection of the entire bony synostosis. Careful dissection with minimal periosteal disruption prevents the further stimulation of bone, limiting recurrence. Identification and protection of neurovascular structures is essential, and the final range of motion should be assessed intraoperatively. Minimal postoperative immobilization is recommended.

Surgical complications

Although the surgical procedure that is used to treat congenital radioulnar synostosis is not exceedingly difficult, it is associated with significant complications 26, including neurovascular compromise and recurrence of ankylosis. The limiting factors for derotation are soft-tissue contracture and neurovascular compromise. Simmons et al recommended that derotations of more than 85º be performed in two stages 14. A low threshold for fasciotomies should be maintained for suspected compartment syndromes.

Congenital radioulnar synostosis prognosis

Overall, results of surgical treatment for posttraumatic radioulnar synostosis are fair at best, with high failure rates and, commonly, loss of approximately one half of the intraoperative rotation. The use of postoperative indomethacin or low-dose limited field irradiation within the first 5 days after surgery has been shown to be effective in limiting the recurrence of synostosis.

- Siemianowicz A, Wawrzynek W, Besler K. Congenital radioulnar synostosis – case report. Pol J Radiol. 2010;75(4):51–54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3389900[↩][↩]

- Congenital radioulnar synostosis in an active duty soldier: case report and literature review. Lescault E, Mulligan J, Williams G. Mil Med. 2000 May; 165(5):425-8.[↩]

- Surgical treatment of acute elbow flexion contracture in patients with congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis. A report of two cases. Masuko T, Kato H, Minami A, Inoue M, Hirayama T. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004 Jul; 86(7):1528-33.[↩]

- Radioulnar Synostosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1240467-overview[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Radioulnar synostosis. https://omim.org/entry/179300[↩][↩][↩]

- Sachar K, Akelman E, Ehrlich MG. Radioulnar synostosis. Hand Clin. 1994 Aug. 10(3):399-404.[↩]

- Dogra BB, Singh M & Malik A. Congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis. Indian J Plastic Surg. 2003; 36(1):36-38.[↩]

- Radioulnar synostosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1240467-overview[↩]

- Bauer G, Arand M, Mutschler W. Post-traumatic radioulnar synostosis after forearm fracture osteosynthesis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991. 110(3):142-5.[↩]

- Henket M, van Duijn PJ, Doornberg JN, Ring D, Jupiter JB. A comparison of proximal radioulnar synostosis excision after trauma and distal biceps reattachment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007 Sep-Oct. 16 (5):626-30.[↩]

- Sauder DJ, Athwal GS. Management of isolated ulnar shaft fractures. Hand Clin. 2007 May. 23(2):179-84, vi.[↩]

- Cleary JE, Omer GE. Congenital proximal radio-ulnar synostosis. Natural history and functional assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985 Apr. 67(4):539-45.[↩][↩]

- Wilkie DP. Congenital radio-ulnar synostosis. Br J Surg. 1914. 1:366-75.[↩]

- Simmons BP, Southmayd WW, Riseborough EJ. Congenital radioulnar synostosis. J Hand Surg Am. 1983 Nov. 8 (6):829-38.[↩][↩]

- Giuffrè L, Corsello G, Giuffrè M, Piccione M, Albanese A. New syndrome: autosomal dominant microcephaly and radio-ulnar synostosis. Am J Med Genet. 1994 Jul 1. 51 (3):266-9.[↩]

- Sonderegger J, Gidwani S, Ross M. Preventing recurrence of radioulnar synostosis with pedicled adipofascial flaps. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2012 Mar. 37 (3):244-50.[↩]

- El-Adl W. Two-stage double-level rotational osteotomy in the treatment of congenital radioulnar synostosis. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007 Dec. 73(6):704-9.[↩]

- Green WT, Mital MA. Congenital radio-ulnar synostosis: surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979 Jul. 61(5):738-43.[↩]

- Smith RJ, Lipke RW. Treatment of congenital deformities of the hand and forearm (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1979 Feb 22. 300(8):402-7.[↩]

- Simcock X, Shah AS, Waters PM, Bae DS. Safety and Efficacy of Derotational Osteotomy for Congenital Radioulnar Synostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2015 Dec. 35 (8):838-43.[↩]

- Hwang JH, Kim HW, Lee DH, Chung JH, Park H. One-stage rotational osteotomy for congenital radioulnar synostosis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015 Oct. 40 (8):855-61.[↩]

- Bishay SN. Minimally invasive single-session double-level rotational osteotomy of the forearm bones to correct fixed pronation deformity in congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis. J Child Orthop. 2016 Aug. 10 (4):295-300.[↩]

- Satake H, Kanauchi Y, Kashiwa H, Ishigaki D, Takahara M, Takagi M. Long-term results after simple rotational osteotomy of the radius shaft for congenital radioulnar synostosis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Aug. 27 (8):1373-1379.[↩]

- Hanel DP, Pfaeffle HJ, Ayalla A. Management of posttraumatic metadiaphyseal radioulnar synostosis. Hand Clin. 2007 May. 23(2):227-34, vi-vii.[↩]

- KELIKIAN H, DOUMANIAN A. Swivel for proximal radio-ulnar synostosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957 Jul. 39-A (4):945-52[↩]

- Hankin FM, Smith PA, Kling TF Jr, Louis DS. Ulnar nerve palsy following rotational osteotomy of congenital radioulnar synostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987 Jan-Feb. 7 (1):103-6.[↩]