Building resilience in children

Resiliency is the ability to ‘bounce back’ from a difficult situation. A resilient person is able to:

- withstand adversity

- learn from their experiences

- cope confidently with life’s challenges.

When psychologists talk about resilience, they’re talking about a child’s ability to cope with ups and downs, and bounce back from the challenges they experience during childhood – for example moving home, changing schools, studying for an exam or dealing with the death of a loved one. Building resilience helps children not only to deal with current difficulties that are a part of everyday life, but also to develop the basic skills and habits that will help them deal with challenges later in life, during adolescence and adulthood.

Resilience is important for children’s mental health. Children with greater resilience are better able to manage stress, which is a common response to difficult events. Stress is a risk factor for mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, if the level of stress is severe or ongoing.

The question for parents then becomes, “How can I help my child become more resilient?”

Psychologists have identified some of the factors that make someone resilient. These include:

- Having a positive attitude

- Being optimistic

- Having the ability to regulate emotions

- Seeing failure as a form of helpful feedback.

- Competence. It’s easy to assume that “competence” simply refers to a child’s mastery of school materials, but in reality, there are many other ways children can build up their feelings of competence. The key to helping children develop a feeling of competence is to give them opportunities to master specific skills or strengths. Luckily, there are plenty of opportunities for skill mastery both at school and at home. Start by giving your child a task that’s a challenge for them initially—assign a complicated chore, ask them to help with dinner and give them a dish to complete, or work with them as they try to master a set of spelling words. When they successfully complete the challenge, compliment them on their effort. Make sure you start small with challenges that your child can realistically accomplish at their stage of development. The sense of achievement they feel from successfully completing a challenge will convince them that they have the ability to meet new, harder challenges.

- Confidence. At the Wisconsin School of Business at the University of Wisconsin, researchers found that higher confidence directly correlates with increased feelings of hope, efficacy, optimism and resilience. They discovered that confident students perform better in school and feel happier with their life. They’re also more likely to bounce back from challenges and overcome failure. Feeling confident is incredibly important to helping children develop a sense of resilience. When children feel confident, they are more likely to take on new tasks, expand their social circle, take risks—and try again if that risk doesn’t pan out. When they fail at a task, confident children are more likely to fault their tactic than to believe that a task is beyond their capabilities. To help your child develop confidence, focus on giving them specific praise that’s closely tied to their efforts, not their intelligence.

- Connected to the people around them. Your sense of resilience is affected by the strength of your social connections. Resilient children often feel a strong bond with friends, siblings, parents and other family members, as well as teachers and other people in caregiver roles. They feel protected and believe that they can count on their network to be there for them if needed. You can help your child develop resilience by being there for them when they face setbacks. Often children feel discouraged when they’re not immediately good at something—such as kicking a soccer ball. Keep encouraging them to try again, recognize their progress and tell them about a time when you experienced a similar setback. Psychologists have found that sharing stories helps people feel more connected to each other, and talking over different approaches they could try next time will help your child feel that you’re invested in their success.

- Secure in their character. Character isn’t something that parents teach or don’t teach—children are actually born with a rudimentary sense of morality. In fact, recent studies from Yale University’s Infant Cognition Center show that children as young as three months naturally show a strong preference for stuffed animals that act “nicely” over those who act “unkindly.” That means they naturally possess the instinct to do the “right” thing. As a parent, you should focus on helping your child develop their natural instincts into an internal moral compass. Sometimes children get confused about what is “right” and need guidance. Other times, selfish instincts still overtake them and they must be corrected. By teaching them standards they should follow, you can help your child feel confident they’ll know how to act in in different situations.

- Personal contributions. If you talk to resilient people in different fields, they all have one thing in common: they believe their actions make a difference. The scientist believes that the time he put in at the lab directly contributed to a breakthrough discovery. The point guard knows the time she stopped a breakaway kept the other team from scoring and gave her team an opportunity to tie the game. You can help your child feel like a contributor by asking them about how their actions helped the group succeed. When children understand how and why their contributions matter, they invest more of themselves into an endeavor. They may play harder defense or ensure they are precise with their measurements. Even if something doesn’t work out, they know that their actions were important. They will push themselves to learn more and study harder, and they will develop more confidence as their work leads to more success.

- Coping skills. A child may appear confident, but only until something doesn’t go according to plan—then they fall apart. A truly resilient child is one who is able to manage their emotions when they face adversity (so they can keep working towards their goal). Resilient children start by facing their feelings about the situation and contain any disappointment, frustration or anger. Then they start thinking about the challenge not as a dead end, but as a stumbling block they can overcome.

- Healthy environment. A child’s environment is the final factor that has a big impact on how confident they feel. When children have consistent caregivers, a predictable routine and clear boundaries from the adults in their life, they feel less stress and are more connected to the people around them. This develops their ability to cope with challenges that arise.

Resilient teenagers are able to control their emotions in the face of challenges such as:

- physical illness

- change of schools

- transitioning from primary school to high school

- managing study workload and exams

- change in family make-up (separation and divorce)

- change of friendship group

- conflict with peers

- conflict with family

- loss and grief.

Resiliency can be taught through practising positive coping skills.

Success in life is never a simple path from A to B. Even if you do everything right, there will still be twists and turns along the way. The key to success is to view those bumps in the road as minor setbacks, not unsurmountable obstacles.

For someone to succeed, they need to have the resilience to bounce back from challenges and overcome failure.

We’ve found that resilient children have seven characteristics in common. The first step to helping your child become more resilient is recognizing which of these key traits your child already possesses. Then use that as a starting place to help your child develop the confidence to meet life’s challenges head-on.

Where does resilience come from?

Resilience is shaped partly by the individual characteristics you are born with (your genes, temperament and personality) and partly by the environment you grow up in — your family, community and the broader society. While there are some things we can’t change, such as your biological makeup, there are many things you can change.

One way of explaining the concept of resilience is to imagine a plane encountering turbulence mid-flight. The turbulence, or poor weather, represents adversity. Different planes will respond to poor weather conditions in different ways, in the same way different children respond to the same adversity in different ways.

The ability of the plane to get through the poor weather and reach its destination depends on:

- the pilot (the child)

- the co-pilot (the child’s family, friends, teachers and health professionals)

- the type of plane (the child’s individual characteristics such as age and temperament)

- the equipment available to the pilot, co-pilots and ground crew

- the severity and duration of the poor weather.

You can all help children become more resilient and the good news is, you don’t have to do it alone. You can ask other adults such as carers and grandparents to help. Building children’s resilience is everyone’s business, and it’s never too early or too late to get started. You’ve got some simple things that you can do in your own home.

Teaching children resilience

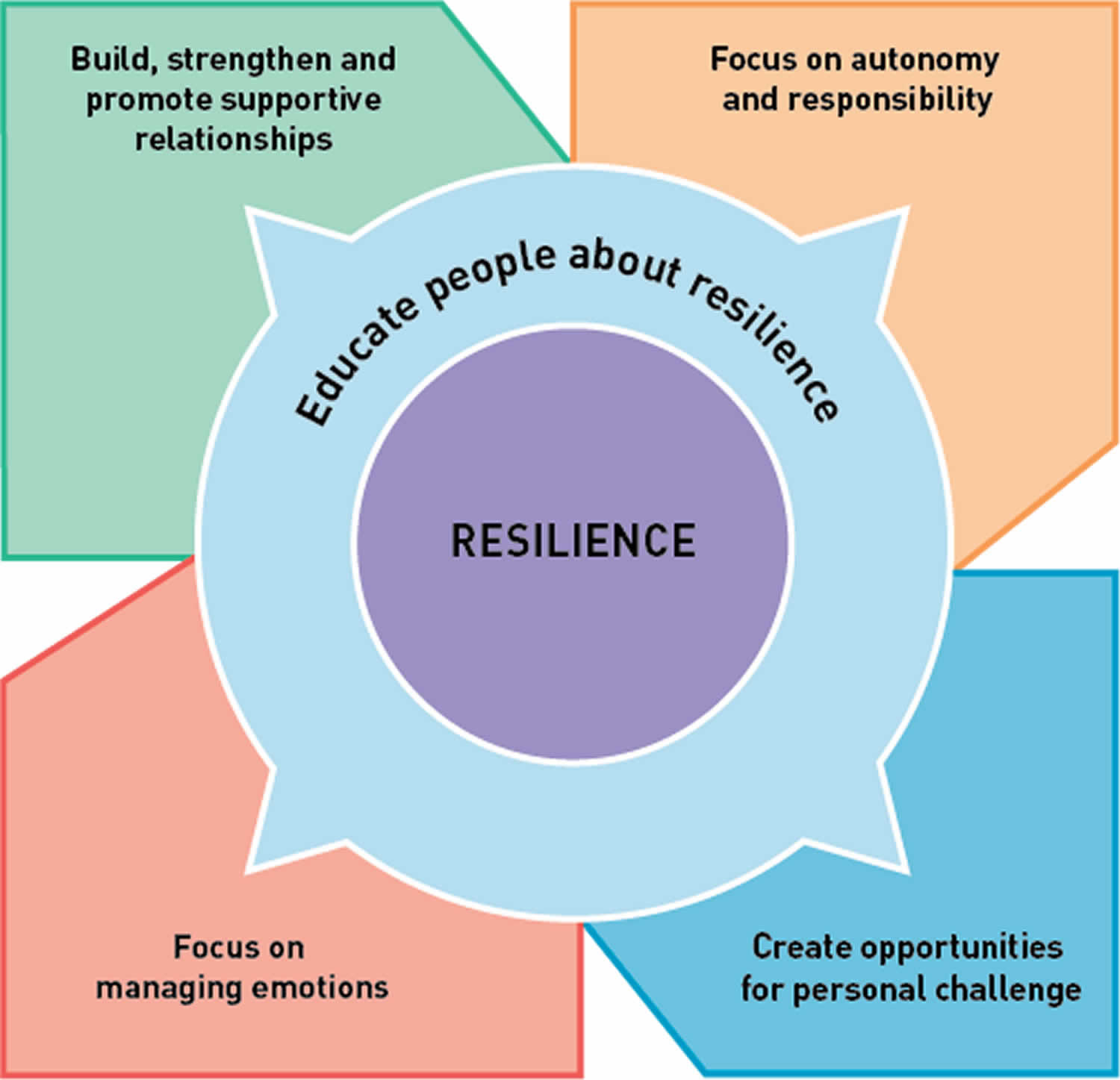

Latest research found that there are five areas that offer the best chance for building resilience in children.

As a parent you can help to develop essential skills, habits and attitudes for building resilience at home by helping your child to:

- build good relationships with others including adults and peers

- build their independence

- learn to identify, express and manage their emotions

- build their confidence by taking on personal challenges

There are some simple things you can do to build your child’s resilience in these areas. You might be able to think of more.

It’s important to remember that the strategies recommended:

- are suitable for everyday use with children aged 0–12 years

- have been tailored for pre-school aged children (1–5 years) and

- primary school aged children (6–12 years)

- should be prioritized in a way that best meets your child’s needs.

If your child is currently experiencing stress, challenges or hardships in life which are affecting their wellbeing, additional professional support may be necessary.

Figure 1. Building resilience in kids

Positive coping strategies

‘Coping’ describes any behavior that is designed to manage the stresses and overwhelming feelings that come with tough situations. By learning and developing positive coping skills in their teenage years, your child will build resilience and wellbeing and be set up with an important skill for life. It’s also important to understand the difference between positive and negative coping skills, and how these strategies can have very different long-term results.

Teaching coping skills to your teenager could be one of the most important skills they learn. They will help your teenager manage any obstacle that may get in the way of their endeavours.

Positive coping skills will help if:

- your child doesn’t cope well with stress

- your child often feels overwhelmed

- your child’s health and wellbeing are negatively impacted by stressful events and difficult emotions.

You can do some simple things to teach your child coping skills and help them put these skills into action. It’s never too early or too late to learn how to do this. It’s a good skill for life.

Talking it out

Encourage your child to speak up if they’re experiencing a tough time, by creating a safe space where their feelings won’t be judged. If what they’re going through doesn’t seem like a big deal to you, keep in mind that it’s very real for them, so be supportive and not dismissive.

It’s also important not to force your child to speak to you if they really don’t want to. Instead, let them know that you’re here to help, but if they’re not comfortable speaking to you (which is okay and shouldn’t be taken personally), encourage them to speak to someone else they trust, such as a friend or another family member.

Taking a break

Taking an active time-out from something that is causing distress is a great way to refocus thoughts and energy. If your child is having difficulty coping, let them know that taking it easy from time to time isn’t being lazy; it’s actually very healthy, especially if they’ve been experiencing a hard time.

Doing something they love

Engaging in enjoyable activities can help lower stress and put them in a positive mindset. Some examples might be:

- taking a walk or using an exercise app

- listening to music

- writing, drawing or painting

- watching a TV show, movie or TED talk

- playing a game online or joining a sports team

- FaceTiming, calling, texting or physically hanging out with friends.

There are heaps of apps out there that can help your teen do activities or learn something new from the comfort of their bedroom.

Eating well and exercising

It’s no myth that physical health has a big impact on mental health. Ensure that your child is eating healthy, nutritious meals that will help their body support them through tough times. Exercise can also help by releasing tension and increasing energy levels.

Try getting as many vegetables, fruits and whole grains into your family’s diet. This might be things like choosing a wholemeal or grainy bread at the supermarket and swapping the after school biscuits to a pieces of fruit. Just as simple, easy and cheap but better for your whole family.

Using relaxation techniques

Teach your child some relaxation techniques that can help with relieving stress.

Engaging in positive self-talk

Let your child know that it’s okay to feel good about, and even to compliment themselves on, all their achievements, however big or small. Start by letting them know why you think they’re great, and encourage them to talk about what they like about themselves. This can help to increase their positive mindset and motivation. Encourage them to be mindful of their achievements and skills (or even to write them down) as a regular reminder of their strengths.

Modeling positive coping behaviors

A really great way to encourage your child to develop positive coping skills is to model the behaviors yourself to show them what positive coping looks like.

Confide in your child about times when you’ve found it hard to cope, and share with them the positive strategies that have worked for you. This will not only make them feel less alone, but will also reinforce the importance of seeking help.

Self-talk

Even though you might not know it, you’re already practicing self-talk.

Self-talk is basically your inner voice, the voice in your mind that says the things you don’t necessarily say out loud. We often don’t even realise that this running commentary is going on in the background, but our self-talk can have a big influence on how we feel about who we are.

The difference between positive and negative self-talk

- Positive self-talk makes you feel good about yourself and the things that are going on in your life. It’s like having an optimistic voice in your head that always looks on the bright side. Examples: ‘I am doing the best I can’, ‘I can totally make it through this exam’, ‘I don’t feel great right now, but things could be worse’

- Negative self-talk makes you feel pretty crappy about yourself and the things that are going on. It can put a downer on anything, even something good. Examples: ‘I should be doing better’, ‘Everyone thinks I’m an idiot’, ‘Everything’s crap’, ‘Nothing’s ever going to get better.’

Negative self-talk tends to make people pretty miserable and can even impact on their recovery from mental health difficulties. But it’s not possible, or helpful, to be positive all the time, either. So, how can you make your self-talk work for you?

3 ways to talk yourself up

- Listen to what you are saying to yourself

- Notice what your inner voice is saying

- Is your self-talk mostly positive or negative?

- Each day, make notes on what you’re thinking

- Challenge your self-talk

- Is there any actual evidence for what I’m thinking?

- What would I say if a friend were in a similar situation?

- Can I do anything to change what I’m feeling bad about?

- Change your self-talk

- Make a list of the positive things about yourself

- Instead of saying, “I’ll never be able to do this”, try “Is there anything I can do that will help me do this?”

Why should I practice?

The more you work on improving your self-talk, the easier you’ll find it. It’s kind of like practising an instrument or going to sports training: it won’t be easy to start with, but you’ll get better with time.

It might not seem like much, but self-talk is a huge part of our self-esteem and confidence. By working on replacing negative self-talk with more positive self-talk, you’re more likely to feel in control of stuff that’s going on in your life and to achieve your goals.

Problem-solving

Problem-solving is an important life skill for teenagers to learn. You can help your child develop this skill by using problem-solving at home.

Everybody needs to solve problems every day. But you’re not born with the skills you need to do this – you have to develop them.

By putting time and energy into developing your child’s problem-solving skills, you’re sending the message that you value your child’s input into decisions that affect her life. This can enhance your relationship with your child.

When solving problems, it’s good to be able to:

- listen and think calmly

- consider options and respect other people’s opinions and needs

- find constructive solutions, and sometimes work towards compromises.

These are skills for life – they’re highly valued in both social and work situations.

When teenagers learn skills and strategies for problem-solving and sorting out conflicts by themselves, they feel better about themselves. They’re more independent and better placed to make good decisions on their own.

Problem-solving steps

Often you can solve problems by talking and compromising. The following six steps for problem-solving are useful when you can’t find a solution. You can use them to work on most problems – both yours and your child’s.

If you show your child how these work at home, he’s more likely to use them with his own problems or conflicts with others. You can use the steps when you have to sort out a conflict between people, and when your child has a problem involving a difficult choice or decision.

This strategy works best when your child is feeling calm and relaxed. If they’re very anxious or angry, help them to calm down first (quiet time, take some deep breaths) or leave problem-solving for another day when they are feeling calmer.

1. Identify the problem

The first step in problem-solving is working out exactly what the problem is. This helps make sure you and your child understand the problem in the same way. Then put it into words that make it solvable. For example:

- ‘I noticed that the last two Saturdays when you went out, you didn’t call us to let us know where you were.’

- ‘You’ve been using other people’s things a lot without asking first.’

- ‘You’ve been invited to two birthday parties on the same day and you want to go to both.’

- ‘You have two big assignments due next Wednesday.’

- ‘You want to go to a party with your friends and come home in a taxi.’

- ‘I’m worried there will be a lot of kids drinking at the party, and you don’t know whether any adults will be present.’

- ‘When you’re out, I worry about where you are and want to know you’re OK. But we need to work out a way for you to be able to go out with your friends, and for me to feel comfortable that you’re safe.’

Focus on the issue, not on the emotion or the person. For example, try to avoid saying things like, ‘Why don’t you remember to call when you’re late? Don’t you care enough to let me know?’ Your child could feel attacked and get defensive, or feel frustrated because she doesn’t know how to fix the problem.

You can also head off defensiveness in your child by being reassuring. Perhaps say something like, ‘It’s important that you go out with your friends. We just need to find a way for you to go out and for us to feel you’re safe. I know we’ll be able to sort it out together’.

2. Think about why it’s a problem

Help your child describe what’s causing the problem and where it’s coming from. It might help to consider the answers to questions like these:

- Why is this so important to you?

- Why do you need this?

- What do you think might happen?

- What’s the worst thing that could happen?

- What’s upsetting you?

Try to listen without arguing or debating – this is your chance to really hear what’s going on with your child. Encourage him to use statements like ‘I need … I want … I feel …’, and try using these phrases yourself. Be open about the reasons for your concerns, and try to keep blame out of this step.

3. Brainstorm possible solutions to the problem

Make a list of all the possible ways you could solve the problem. You’re looking for a range of possibilities, both sensible and not so sensible. Try to avoid judging or debating these yet.

If your child has trouble coming up with solutions, start her off with some suggestions of your own. You could set the tone by making a crazy suggestion first – funny or extreme solutions can end up sparking more helpful options. Try to come up with at least five possible solutions together.

Write down all the possibilities.

4. Evaluate the solutions to the problem

Look at the solutions in turn, talking about the positives and negatives of each one. Consider the pros before the cons – this way, no-one will feel that their suggestions are being criticised.

After making a list of the pros and cons, cross off the options where the negatives clearly outweigh the positives. Now rate each solution from 0 (not good) to 10 (very good). This will help you sort out the most promising solutions.

The solution you choose should be one that you can put into practice and that will solve the problem.

If you haven’t been able to find one that looks promising, go back to step 3 and look for some different solutions. It might help to talk to other people, like other family members, to get a fresh range of ideas.

Sometimes you might not be able to find a solution that makes you both happy. But by compromising, you should be able to find a solution you can both live with.

5. Put the solution into action

Once you’ve agreed on a solution, plan exactly how it will work. It can help to do this in writing, and to include the following points:

- Who will do what?

- When will they do it?

- What’s needed to put the solution into action?

You could also talk about when you’ll meet again to look at how the solution is working.

Your child might need some role-playing or coaching to feel confident with his solution. For example, if he’s going to try to resolve a fight with a friend, he might find it helpful to practice what he’s going to say with you.

6. Evaluate the outcome of your problem-solving process

Once your child has put the plan into action, you need to check how it went and help her to go through the process again if she needs to.

Remember that you’ll need to give the solution time to work, and note that not all solutions will work. Sometimes you’ll need to try more than one solution. Part of effective problem-solving is being able to adapt when things don’t go as well as expected.

Ask your child the following questions:

- What has worked well?

- What hasn’t worked so well?

- What could you or we do differently to make the solution work more smoothly?

If the solution hasn’t worked, go back to step 1 of this problem-solving process and start again. Perhaps the problem wasn’t what you thought it was, or the solutions weren’t quite right.

When conflict is the problem

During adolescence, you might clash with your child more often than you did in the past. You might disagree about a range of issues, especially your child’s need to develop independence.

It can be hard to let go of your authority and let your child have more say in decision-making. But she needs to do this as part of her journey towards being a responsible young adult.

You can use the same problem-solving steps to handle conflict. When you use these steps for conflict, it can reduce the likelihood of future conflict.

Let’s imagine that you and your child are in conflict over a party at the weekend.

You want to:

- take and pick up your child

- check that an adult will be supervising

- have your child home by 11 pm.

Your child wants to:

- go with friends

- come home in a taxi

- come home when she’s ready.

How do you reach an agreement that allows both of you to get some of what you want?

The problem-solving strategy described above can be used for these types of conflicts. It follows these steps:

1. Identify the problem

Put the problem into words that make it workable. For example:

- ‘You want to go to a party with your friends and come home in a taxi.’

- ‘I’m worried there will be a lot of kids drinking at the party, and you don’t know whether any adults will be present.’

- ‘When you’re out, I worry about where you are and want to know you’re OK. But we need to work out a way for you to be able to go out with your friends, and for me to feel comfortable that you’re safe.’

2. Think about why it’s a problem

Find out what’s important for your child and explain what’s important from your perspective. For example, you might ask, ‘Why don’t you want to agree on a specific time to be home?’ Then listen to your child’s point of view.

3. Brainstorm possible solutions

Be creative and aim for at least four solutions each. For example, you might suggest picking your child up, but he can suggest what time it will happen. Or your child might say, ‘How about I share a taxi home with two friends who live nearby?’

4. Evaluate the solutions

Look at the pros and cons of each solution, starting with the pros. It might be helpful to start by crossing off any solutions that aren’t acceptable to either of you. For example, you might both agree that your child taking a taxi home alone is not a good idea.

You might prefer to have some clear rules about time – for example, your child must be home by 11 pm unless otherwise negotiated.

Be prepared with a back-up plan in case something goes wrong, like if the designated driver is drunk or not ready to leave. Discuss the back-up plan with your child.

5. Put the solution into action

Once you’ve reached a compromise and have a plan of action, you need to make the terms of the agreement clear. It can help to do this in writing, including notes on who will do what, when and how.

6. Evaluate the outcome

After trying the solution, make time to ask yourselves whether it worked and whether the agreement was fair.

Managing emotions

Primary school kids are still learning to identify emotions, understand why they happen, and how to manage them. As children develop the things that provoke emotional responses change, as do the strategies they use to deal with them.

Some children show a high level of emotional maturity while quite young, whereas others take longer to develop the skills to manage their emotions. This is really normal – everyone develops at different stages and paces.

All children need support from their parents and caregivers to understand their feelings, as well as encouragement to work out ways to manage them – some might just need a bit of extra help to figure things out.

If your child is showing signs of emotional or behavioral difficulties it’s important to seek help early and address any problems before they get worse. Getting support for yourself, through family and friendship networks or your doctor, is also very important. This support helps to build your own resilience, so you can care for your kids.

Understanding your child’s feelings

Supporting children’s emotional development starts with paying attention to their feelings and noticing how they manage them. By acknowledging children’s emotional responses and providing guidance, you can help kids understand and accept feelings, and develop effective strategies for managing them.

- Tune in to children’s feelings and emotions. Some emotions are easily identified, while others are less obvious. Tuning into children’s emotions involves looking at their body language, listening to what they’re saying and how they’re saying it, and observing their behavior. Figuring out what they’re feeling and why means you can respond more effectively to their needs, and help them develop specific strategies – for example, when we’re feeling nervous, we can try taking big deep breaths.

- Validate your child’s emotional experiences. Listen to what children say and acknowledge their feelings. This helps children to identify emotions and understand how they work. Being supported in this way helps children work out how to manage their emotions. You might say, “You look worried. Is something bothering you?” or “It sounds like you’re really angry. Let’s talk about it.”

- Set limits in a supportive way. Kids need to understand that having a range of emotions and feelings is OK, but there are limits to how feelings should be expressed appropriately. You can set limits, talk about why these exist, and how one person’s feelings shouldn’t make someone else feel upset. For example, “I know you’re upset that your friend couldn’t come over, but that doesn’t make it OK to yell at me.”

- View emotions as an opportunity for connecting and teaching. Children’s emotional reactions provide ‘teachable moments’ for helping them understand emotions and learn effective ways to manage them. You might say, “I can see you’re really frustrated about having to wait for what you want. Why don’t we read a story while we’re waiting?”

- Be a role model. Children learn about emotions and how to express them appropriately by watching others – especially parents and other family members. Showing kids the ways you understand and manage emotions helps them learn from your example. If you lose your temper (hey, it happens!), apologize and show how you might make amends.

- Encourage problem-solving. Help children develop their skills for managing emotions by encouraging them think of different ways they could respond. You might say, “What would help you feel brave?” or “How else could you look at this?”

- Providing security. Kids are reassured by knowing that a responsible adult is taking care of them and looking after their needs. Parents and other family members can help children manage their emotions by creating a safe and secure environment. Kids need extra support from you when they’re feeling tired, hungry, sad, scared, nervous, excited or frustrated. Regular routines, such as bedtimes and mealtimes, reduce the impact of stress and helps to provide a sense of stability for kids.

Dealing with difficult emotions

Modelling behavior when you’re feeling stressed or upset helps kids develop their own strategies for coping with their emotions.

You can say:

- “I’m getting too angry. I need some time out to think about this.”

- “I’m feeling really tense. I need to take some deep breaths to calm down.”

Being ready to apologize, listening to how the other person feels and showing you appreciate their position is a critical skill for building strong and supportive family relationships.

Admitting to having difficult feelings is not a sign of weakness or failure. Instead, it sets a good example by showing that everyone has difficult feelings at times and that they are manageable.

Dealing with stress

Every child is an individual and will approach life and its challenges in completely different ways. By paying attention and listening to your child, you’ll be able to identify their stressors and help them cope. Some common things that cause kids stress are:

- relationships with friends

- teasing and bullying at school

- family relationships – tension with parents and siblings

- being tired

- being hungry

- worrying about world events

- being stuck inside because of weather.

Helping kids stay calm

Check out these strategies you can use to help your child shift from feeling stressed, anxious or frightened to feeling safe and calm, and ready to move on.

- Watch closely. How does your child take in information? How do they seek out social connection and communicate?

- Respond. Acknowledge their feelings and respond with reassuring words or a hug. Talk about helpful ways of managing feelings and encourage your child to try out different options.

- Remember that it’s not always easy for kids to know what’s bothering them, and they may not always be able to talk about it.

- Show empathy. Try to see things from your child’s perspective and understand their motives. This helps you to ward off any potential problems and respond quickly and appropriately.

- Use problem-solving techniques. Talk about the things that are bothering them. Break the problems down together and help your child see the different perspectives and solutions. Find out more about problem-solving

- Provide structure and predictability. Have age-appropriate routines and limits.

- Include relaxation breaks in your day. Give stretching, exercise or quiet time a go.

- Teach by showing. Show kids how you manage your own feelings effectively. Acting calmly will help to reassure your child that they too can manage difficult feelings.

Useful questions to ask yourself:

- How do you know when your child is feeling overwhelmed or stressed?

- What do you do to help them become calmer? Does it work?

- What else could you try?

Developing communication skills

Good communication is always a two-way thing. Listening to children is as important as what you say to them and how you say it. This might not always be easy – especially when you’re tired, busy or have to deal with complaining or conflict – but it’s important to model good communication skills so your kids can learn from you.

Approaching communication as a conversation between family members helps kids develop skills for life, setting them up for strong, respectful relationships and feeling able to ask for support when they need it.

Communicating as a family

Talking together and discussing everyday things helps family members feel connected. It builds trust and makes it easier to ask for and offer support. Making time to listen and show interest encourages kids to talk and helps you understand how they think and feel. Listening actively helps to build relationships and communication skills.

To get your kids to talk more, take notice of the times when they do talk. Often this is while doing everyday things like household chores or while playing games together. Use these relaxed times to get a conversation going with them. Similarly, it’s important to make sure that the adults in the family have relaxed times to talk together.

Top tips for communicating with your kids:

- Make talking part of your routine. Make time to chat with your kids every day. If your child wants to share something, give them your full attention and listen without getting distracted.

- Let your child talk about whatever interests them. Show respect for their interests, even if listening to a run-down of the world they’ve built in Mine Craft or their expanding Pokemon collection isn’t the most exciting topic for you.

- Talk about your interests with your kids. Whether it’s sport, music or cooking, sharing the things that make you happy is important too.

- Show affection. We communicate through our actions as well as words. Hugging and showing affection makes kids feel loved and content.

- Reinforce that you’re there for them. Let your kids know that they can talk to you about anything. Setting this up early will help down the line as they get older and become more independent.

When things get tough

Talking about what’s bothering us can be hard – for both kids and adults. We need to feel safe and supported, and trust that we’ll be listened to and understood.

Asking how your child feels and listening non-defensively allows you to work together to solve problems. Blaming, judging or criticizing will quickly shut down real communication and very often leads to arguments.

Listening carefully to the other person’s perspective and explaining your own feelings and views (“I’m disappointed that…” or “I’m upset that …”) rather than accusing (“You don’t care…” or “You’ve upset me…”) helps to defuse arguments and supports effective communication.

Build supportive relationships

Quality relationships are important for resilience. You can help develop your child’s resilience by helping them build and strengthen their relationships with other children, and with significant adults in their lives – including your parent-child relationship.

It is important to remember to:

- spend quality time with your child

- support your child to build relationships with other adults

- help your child develop social skills and friendships with peers

- help your child to develop empathy.

Spend quality time with your child

Connect with your child. Connect with your child by doing things together that you both enjoy – for example, taking walks or watching your favorite movies together. Use this quality time to talk with your child and stay connected with the things that are important to them and any concerns they have.

Show warmth and affection

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Warmth and affection is important for your child’s development. Touch is particularly important in the first few years of life for creating a strong attachment between adult and child. Learn how your child likes to be shown affection – for example, a hug or a kiss – and show your child regular affection. It will help to establish a parent-child relationship of trust.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Use your quality time together to show affection and acceptance while respecting their individual comfort level (these may vary in public places such as at school). Talk with your child about who they are, what they value, what they like and don’t like – be accepting of differences that exist between you and your child.

Talk with your child

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Talk with your child about things that interest them. Ask them open questions such as, “Tell me about all the things you like about going to the park”. “Tell me about the things that you don’t like about going to park.” By asking open questions, you’ll get a unique insight into your child’s world and what they value.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Talk often with your child about things that are happening in their life – interests, sports, friends, teachers, school etc. Use open questions to talk with them about these things, such as “tell me all about school”. By asking open questions, you’ll get a unique insight into your child’s world and what they value. If you ask closed questions like, “Did you enjoy school today?”, you’ll most likely get short responses and have little understanding about your child’s day.

Do activities that extend your child’s development

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Do activities with your child that extend their development. For example, building blocks are good for developing children’s fine motor skills. As this is a developing skill, your child may find it difficult to master. Encourage your child in a positive and supportive way. You could say, “I can see this is difficult and it’s so good that you are trying!”

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Listen carefully if your child expresses any worries and try to understand their point of view. Avoid making assumptions on your child’s behalf. Listen to your child’s description of the challenge they’re experiencing and find out what they value. For example, ask questions like, “Tell me about what’s difficult for you”.

Teach your child about emotions

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Young children are learning about their emotions. You can help your child to learn about how they feel, by labeling emotions in themselves. For example, if they experience frustration when building blocks.

- Primary school aged kids (6-12 year olds). When your child is having a hard time, ask them how you can best support them. This will give them a sense of control and choice in handling the situation.

Support your child to build relationships with other adults

- Help your child connect with family history. Help your child connect to the people and history in your family including aunts, uncles, grandparents and cousins, as well as other important adults who may not be related but are also important. Tell stories from the past about family members, look through old photographs and share memories. Encourage and organise for your child to spend time with family and friends. Older children could also keep in contact by phone, email, Messenger or Skype. You play a vital role in helping your child to develop good relationships with extended family members and friends.

- Involve your child in local community activities:

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Encourage your child’s sense of belonging by involving them in the local community from an early age. There are many great, low cost things to do in local communities – such as groups at local libraries and community playgroups, which allow them (and you) to connect with others in the local community.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Encourage your child to connect with different types of people in your community – by attending local community events and working bees at your child’s school. This will expose your child to different types of people, and give them a greater sense of purpose and belonging outside of your immediate family.

Friendships are important to your child’s development. Help your child to practise and improve their social skills so that they can form friendships with their peers. Kids learn how to manage relationships by observing the ways that other people around them relate to each other. You are their role model.

Encourage your child to socialize

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). There are many social skills that your child will develop early in life that will support them to form friendships as they grow up. These skills include learning to share, taking turns, following rules, compromising and self-control. You can role model these skills at home. Give your child a head start by taking turns when playing board games or compromising when family members have different preferences.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Your child’s opportunities to make friends expand once they go to school, as does their autonomy in making friends. Encourage your child to participate in activities that allow them to meet new people, for example, through extra-curricular activities such as sport, arts and music. Pay attention to the friends your child is making.

Encourage your child to play with friends

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Young children (under the age of four) tend to play alongside each other rather than ‘playing with’ other children, though this usually changes around the time they reach pre-school. Take your child to places where there will be other children to play with. For younger children, you should monitor their play so that you can intervene if things start to go wrong, such as if your child wants the same toy as another child. Take the time to reinforce sharing and taking turns when these situations arise.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Encourage your child to invite other children over to play. If your child is new to having friends over, or has had difficulty in the past, talk with them about: suitable activities for when their friend visits; how your child will know when it’s time to change games; and how your child will know if their friend is having a good time.

Help your child to support others

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Help your child to develop empathy towards other children as outlined in the next section.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Help your child to think about ways they can support their friends when they’re going through a challenging time. Come up with a list of ideas and put all the ideas together in a folder at home and refer to them regularly. Use the opportunity to talk with your child about how they would like to be supported in a similar situation.

Help your child to develop empathy

Empathy is important to building good relationships because it involves being sensitive and understanding the emotions of others and responding in appropriate ways.

- Role model positive relationships. Provide your child with opportunities to practice being empathetic. Your child will learn how to be empathetic by observing you and other adults in their lives. Try to role model positive relationships and interact with others in a kind and caring way.

- Read age appropriate books

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Read books with your young child about feelings.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Read age appropriate books with your child about a character who is having a difficult time. Ask your child to reflect on the emotional experience of the character and imagine how they would feel in the same circumstance. Ask your child how they would like others to respond to them if that happened.

- Empathize with your child

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Empathize with your child. For example in a thunder storm you could say “the thunder is really loud. Are you scared of the thunder? You can stay close to me until the thunder passes.”

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Talk with your child about other children they know who may be having a tough time. Ask your child how they would feel in that situation, and what they can do to support the child.

- Talk with your child about others’ feelings

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Talk with your child about others’ feelings. For example, “Raimy is feeling sad because you took his toy truck. Please give Raimy back his truck. You choose another one to play with.” You can also use pretend play to talk about feelings as you play with your child.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Talk with your child about ways to show empathy such as: listening; opening-up and sharing with others; using physical affection (if appropriate); noticing the feelings, expressions and actions of others; not making judgements; and offering help to others.

- Encourage empathy and role model being curious

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Show your child how they can show empathy. For example, “Let’s get Chitra some ice for her sore leg.”

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Role model being curious. Invite your child to be curious about others. Notice the feelings, expressions and actions of others.

- Validate your child’s difficult emotions

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Validate your child’s difficult emotions. Sometimes when children are sad, angry or disappointed, we try to fix the problem straight away and protect our child from any pain. However, these feelings are part of everyday life and our children need to learn how to cope with them. Labelling and validating difficult emotions helps children learn to handle them. For example, “I can see you’re angry that I’ve taken away your iPad. I understand that and I know you like using your iPad. It’s OK if you’re angry. When you’re finished feeling upset, would you like to come outside and help me dig in the garden or shall we make some muffins in the kitchen?”

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Validate your child’s difficult emotions. Sometimes when children are sad, angry, or disappointed, we try to fix the problem straight away and protect our child from any pain. However, these feelings are part of everyday life and our children need to learn how to cope with them. For example, “I can see that you are sad because you were not invited to Joseph’s party. It’s normal to feel that way but it’s important to remember that you have many friends who enjoy spending time with you.”

- Interact with a diverse range of people

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Look for opportunities to volunteer with your child. This will help your child to understand the needs of others and allow them to interact with a diverse range of people.

- Practice experiential empathy

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Help your child to practice ‘experiential’ empathy by taking on the tasks of someone else (perhaps yourself) for a day.

Focus on autonomy and responsibility

Autonomy and responsibility play an important role in building children’s resilience. You can encourage your children to take on responsibilities and develop a sense of autonomy. It’s important to remember that as parents, it’s natural for us to want to protect our children from negative experiences, but it’s important not to shield them completely from life’s challenges. Working through difficulties and problems – with adult support as required – will give your child a chance to learn about themselves, develop resilience, and grow as a person.

- Build your child’s independence

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Build your child’s autonomy and independence. For example, encourage your child to dress themselves or give money to a shopkeeper – gradually increase the complexity of the tasks as your child builds their independence.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Build your child’s autonomy and independence. You could encourage your child to prepare their own school lunch or contribute to cooking the family meal – gradually increase the complexity of the tasks as your child builds their independence.

- Talk to your child about problem solving

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Talk to your child about how they might address a problem, rather than rushing in to solve the problem for them. For example, ask your child what he/she might do if they wish to play with the toy that another child is playing with.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Talk to your child about how they might address a problem, rather than rushing in to solve the problem for them. For example, ask your child what they might do if they forget their lunchbox, so the child doesn’t have to rely on their parents to deliver the lunchbox to school.

- Allow your child to make decisions

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Give your child opportunities to make meaningful decisions. For example, give choices and allow your child to select their preference. For example, allow them to decide the order in which certain things will be done, or which book they want to read.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Talk to your child about how he/she can develop strategies for dealing with difficult situations. For example, help your child to develop a plan for when they feel left out of a friendship group, of if they are feeling stressed about school tests. Remind your child of all the people around them who can help. Encouraging your child to come up with their own solutions helps them to learn problem solving.

- Provide opportunities for free play

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Provide opportunities for free play – open ended and improvised play – such as building blocks, playing with teddies or action figures, or painting on blank paper are great examples of free play for young children.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Provide your child with opportunities to make meaningful decisions. For example, let them decide how they want to arrange their bedroom, or what they want to do as an end of year celebration.

- Being bored is not necessarily bad

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Being bored occasionally is not necessarily bad for children. Your child may come up with their own ideas (such as devising a new game or building a cubby house). These occasions help children develop their sense of autonomy.

- Be a role model for your child. Be a role model for your child. Try to model ‘healthy thinking’ when facing challenges of your own. You can do this by thanking other people for their support, and saying, “Things will get better soon. I can cope with this”. This shows that you expect that good things are possible. You can also role model calm and rational problem-solving when something doesn’t go as expected. Talk out loud the thought process you are having in solving a problem. Your child can see what problem-solving looks like, and also that the problem can be worked through in a calm way to find a solution.

- Healthy thinking means looking at life and the world in a balanced way (Canadian Mental Health Association, 2011). Healthy thinking teaches children to know how their thoughts (both helpful and unhelpful) affect problems or feelings in everyday life. With practice, children can learn to use accurate thoughts that encourage them instead of negative thoughts that discourage them.

Create opportunities for personal challenge

Provide your child with opportunities to build their confidence and learn how to deal with obstacles, success and failure when they undertake personal challenges.

It is important to remember the following:

- One idea that is very relevant to building children’s confidence by taking personal challenges is ‘healthy risks’. Healthy risks are age and developmentally appropriate risks such as walking to the shops with a sibling or alone. Healthy risks are not only about the risk of getting physically hurt, but also about the risk of losing, failing or making a mistake.

- As a parent, you need to define what you consider to be a ‘healthy risk’ for your child – depending on their age, maturity and your own comfort level. It may be useful to ask yourself what risks you have let your child take in the past. What was the outcome? Would you encourage your child to take that risk again? It may be helpful to discuss ‘healthy risk-taking’ with other parents.

Some examples of how you might do this:

- Teach your child to ‘have a go’. Teach your child to adopt a healthy attitude of ‘having a go’ early in life. Kids learn through trial and error and they need to learn how to tolerate failure when it occurs. Not learning to tolerate failure can leave children vulnerable to anxiety, and it can make them give up trying – including trying new things.

- Allow your child to experience everyday adversity

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Give your child opportunities to experience ‘everyday’ adversity. This might involve going for a walk in the bush, even when there’s a chance of rain. Coping with the rain will help your child learn how to manage obstacles.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Give your child opportunities to experience ‘everyday’ adversity. This might include being involved in sporting activities such as Little Athletics where there is the likelihood of losing. Learning how to deal with the disappointment of losing will help your child learn how to manage obstacles and other set-backs they experience in life.

- Encourage your child to do free play

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Encourage your child to do free play activities (i.e. open ended and improvised activities). For example, give your child a box containing a range of different items, or a blank sheet of paper. Allow your child to determine what they will do with the items. Free play provides children with the opportunity to explore and helps build resilience.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Encourage your child to do free play activities (i.e. open ended and improvised activities). For example, give your child a box of raw materials such as recycling items and allow your child to determine what they will do them. Free play provides children with the opportunity to explore and helps build resilience.

- Encourage your child to build independence

- Pre-school aged kids (1–5 year olds). Encourage your child to build their independence by gradually increasing the difficulty of things they can do at home. For example, young children can help you to prepare the evening meal by setting the table or by assisting with food preparation such as washing the lettuce, or buttering the bread. Slowly increase the difficulty of the tasks as their skills develop.

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Encourage your child to take ‘healthy risks’. For example, this might involve walking to or home from school, alone or with a sibling. You may start by driving or walking your child halfway to school and allowing them to walk the remainder of the distance alone, or with a sibling.

- Talk to your child about self talk

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Talk with your child about self-talk and how you can shift the focus of self-talk in situations that aren’t going so well. Help your child practice reframing their self-talk. For example, a child might interpret being left out of a group as, ‘They don’t like me. I’m not worth liking. I’m not a nice person’. You can help them to shift their thinking by reminding them of times they’ve played happily with others, so they have good memories to call on.

- Help your child deal with difficult situations

- Primary school aged kids (6–12 year olds). Help your child develop strategies to deal with difficult situations and encourage them to come up with their own solutions.

- Explore the benefits of community based organizations. Explore the benefits of community based organizations that provide opportunities for healthy risk-taking and developmental growth through activities such as orienteering, camping, leadership, physical activity, volunteering, and the arts (e.g. drama, theater groups, dance classes).

Encouraging independence

As children get older they can manage more and more tasks and decisions on their own. Some kids are confident trying new things, while others need a bit more encouragement.

Finding the right level of support can also be tricky – you’re trying to hit a sweet spot where kids are challenged and can learn through trial and error, but also feel secure and know that they have adult backing. It can be an adjustment for parents too, but one that pays off as kids’ self-confidence, maturity and resilience grows.

Increasing autonomy through new experiences

Taking risks and being impulsive can be part of a younger child’s quest for new experiences, and kids are notorious for testing boundaries. You can help by providing structure and gradually introducing different challenges, giving them space to experiment and figure things out by themselves within the safety of your family.

Taking them to a different playground with bigger play equipment, getting them to help when you’re preparing meals and encouraging them to play on their own for short time periods are all ways you can support this growing independence.

It’s important to remember that the part of our brain that processes consequences develops much later than the parts responsible for actions – in short, kids often do things without thinking through what will happen as a result. Make sure you balance their growing need for independence with enough supervision to ensure they’re always safe from harm – to themselves and other kids.

Establish clear limits

It’s important to be clear about what behavior is OK and not OK in your family. Sit down together and talk about the rules of the house, and set the consequences for breaking those rules. It can help to display the rules somewhere visible – on a poster, behavior chart or the fridge.

For younger children, keeping it simple works well – for example no hitting, no breaking things, inside voice/outside voice etc. Consequences can also be pretty straightforward, such as time out, or removal of a toy for a time period.

As kids get older you can keep updating the family rules together. Remember that rules don’t always have to be negative. Think of them as guidelines for how everyone in the family treats each other, and expects to be treated in return.

Pay attention to their needs

Paying attention to your child’s emotional needs helps them feel secure and gives them the confidence to be more independent.

Here are some ideas:

- Pick some fun activities that they enjoy and that give you a chance to spend some one-on-one time together. Things like baking, going for a day trip, or making a book of family photos are all good options.

- Develop a habit of doing something special with each child once a month away from the rest of the family.

- Try and eat dinner together as often as you can. This can be challenging, as younger kids often need to eat earlier and might not want the same food as the rest of the family. Dishes like tacos or mini pizzas can work well as a family meal as everyone gets to choose their own ingredients.

- Encourage friendships, especially ones they’ve made themselves.

Know when to back off

It’s important to balance adequate supervision with giving kids the space to figure things out on their own. Give them a chance to make mistakes and try to avoid taking over. If you’re unsure if you’re stepping into a situation too often or too early, ask yourself “Do I really need to get involved?” and, “What would be the worst thing that can happen if I don’t step in?”

Dealing with bullying

Bullying is all about power – making yourself feel bigger and stronger by putting someone else down.

It involves deliberately and repeatedly attempting to hurt, scare or exclude someone. And it can be overt – hitting, pushing, name-calling – or more indirect, such as deliberately leaving someone out of games, spreading rumors about them, or sending them nasty messages.

Whatever form it takes, bullying can be incredibly damaging. It causes distress and can lead to loneliness, anxiety and depression. Bullying can also affect children’s concentration and achievement at school.

When children have been bullied they may:

- not want to go to school

- be unusually quiet or secretive

- be more unhappy or anxious than usual, especially before or after school, sport or wherever the bullying is happening

- not have many friends

- become more isolated – stop hanging around with friends or lose interest in school or social activities

- seem over-sensitive or weepy

- have angry outbursts

- have trouble sleeping

- complain about having headaches, stomach aches or other physical problems.

You may notice that their belongings have been damaged or are missing.

There might be other reasons for some of these signs in your child, so it’s best to talk together about what’s going on and any changes you’ve noticed.

Raising the issue

If you suspect your child is being bullied, it can be hard to know how to raise it with them. Some kids try and hide what’s happening, or feel ashamed, afraid or might not want you to worry or make a big deal. Often children just want the bullying to stop without confronting the issue or drawing attention to it.

They might find it uncomfortable discussing their feelings and emotions openly with you, or get angry and defensive when you ask if they’re OK. Try to stay calm, and realize you may need to raise the conversation in different ways over time to get a response.

What you can do to help

- Listen and provide support.

- Try to understand what has been happening, how often and how long it has been happening

- Encourage social skills and clear communication – being assertive, telling the bully to stop and seeking help

- Come up with some practical steps and strategies together – who they can talk to at school and what they can do when the bullying is happening.

- Talk with your child’s teacher and ask for help.

- Keep talking with the school until your child feels safe.

If your child tells you about bullying they’ve seen or heard at school:

- encourage them to stand up for the child who is being bullied

- encourage your child to report what they’ve seen or heard to school staff

If your child is doing the bullying:

- make sure your child knows bullying behavior is unacceptable and why

- try to understand the reasons why your child has behaved in this way and look for ways to address problems

- encourage them to think about the other person’s perspective, such as “how would you feel if …”

- help your child think of alternative ways of dealing with situations and communicating their feelings.

To help prevent cyber-bullying you can:

- supervise children’s use of electronic devices

- talk to kids about staying safe online. It can help to remind them that the internet is still ‘real life’ and you should behave the same – and expect the same behavior from others – as you would in person.