SAPHO syndrome

SAPHO syndrome involves any combination of Synovitis (inflammation of the joints), Acne (conglobata or fulminans), Pustulosis (thick yellow blisters containing pus) often on the palms and soles, Hyperostosis (increase in bone substance) and Osteitis (inflammation of the bones) 1. The cause of SAPHO syndrome is unknown. SAPHO syndrome belongs to the autoinflammatory bone disorders, in which dysregulation of innate immunity causes inflammation in sterile bone 2. Autoinflammatory bone disorders also include chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis and Majeed syndrome 3. It remains to be clarified how these diseases differ from each other 4.

SAPHO syndrome affects individuals of any age, ranging from childhood to adulthood, and its prevalence has been estimated to be no greater than one in 10,000 in Caucasians and is rarer in Asians 5. Most patients present with local inflammatory symptoms of pain, swelling, and limitation of movement at the site of active involvement without suppuration 6.

SAPHO syndrome is known to present at any age ranging from childhood to adulthood and is characterized by repeated episodes of remission and recurrence 7. SAPHO syndrome can be difficult to diagnose because of its variable clinical presentation, widespread distribution, and broad spectrum of imaging features 8. Generally, combinations of osteoarticular and skin manifestations lead to its diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of SAPHO syndrome remains unknown and several hypotheses, such as infectious, immunological, and genetic mechanisms, have been proposed. An infective cause is a widely accepted theory, and it is described as an autoinflammatory process triggered by low-virulence pathogens 9. Propionibacterium acnes, a member of normal flora of the skin and gastrointestinal tract, is occasionally identified from osteoarticular biopsy samples. However, in many instances, biopsy culture is negative and antibiotic therapy is generally ineffective 10. SAPHO syndrome shares clinical and radiologic features with spondyloarthropathy, including sacroiliitis, enthesis, paravertebral ossifications, and ankylosis, and many times is associated with psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. However, its consideration as a variant of spondyloarthropathy is controversial 11. Serum rheumatoid factor is usually absent, and human leukocyte antigen-B27 is positive in 4–18% of patients, which is less frequent compared to spondyloarthropathy 12.

SAPHO syndrome is classified along three different spectrums:

- Pustulo-psoriatic hyperostotic spondylarthritis,

- Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis of the adult age,

- Imperfect forms of these.

Prevalence of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis is estimated at 0.04% whilst the other entities are rarer.

SAPHO syndrome treatment is focused on managing symptoms 13.

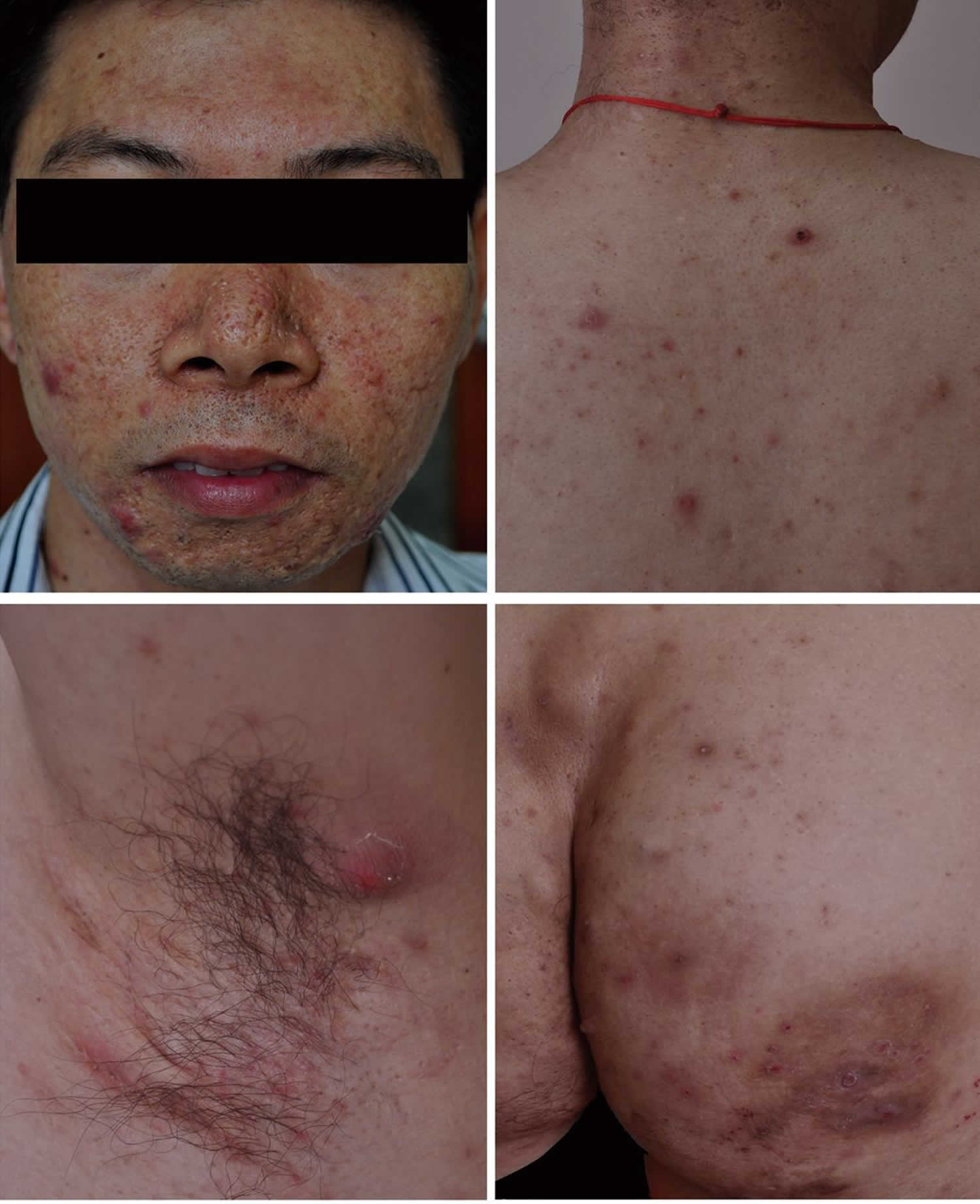

Figure 1. SAPHO syndrome

Footnote: Clinical features of the patient with synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome. Inflamed papules, nodules, cyst, and scars on the face, nape, back, armpit, and buttocks.

[Source 14 ]SAPHO syndrome causes

The cause of SAPHO syndrome is unknown. The pathogenesis of SAPHO syndrome remains unknown and several hypotheses, such as infectious, immunological, and genetic mechanisms, have been proposed. An infective cause is a widely accepted theory, and it is described as an autoinflammatory process triggered by low-virulence pathogens 9. Propionibacterium acnes, a member of normal flora of the skin and gastrointestinal tract, is occasionally identified from osteoarticular biopsy samples. However, in many instances, biopsy culture is negative and antibiotic therapy is generally ineffective 10. SAPHO syndrome shares clinical and radiologic features with spondyloarthropathy, including sacroiliitis, enthesis, paravertebral ossifications, and ankylosis, and many times is associated with psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. However, its consideration as a variant of spondyloarthropathy is controversial 11. Serum rheumatoid factor is usually absent, and human leukocyte antigen-B27 is positive in 4–18% of patients, which is less frequent compared to spondyloarthropathy 12.

SAPHO syndrome symptoms

SAPHO syndrome is characterized by any combination of:

- Synovitis (inflammation of the joints)

- Acne (conglobata or fulminans)

- Pustulosis (thick yellow blisters containing pus) often on the palms and soles and similar to palmoplantar pustular psoriasis)

- Hyperostosis (increase in bone substance)

- Osteitis (inflammation of the bones)

Other skin lesions seen in SAPHO syndrome include: hidradenitis suppurativa and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp.

The skin lesions in SAPHO syndrome are characterised on skin biopsy by collections of inflammatory cells, known as neutrophilic pseudoabscesses.

Bony involvement mostly affects the breast bone (sternum), resulting in decreased mobility due to pain, tenderness and swelling. The collar bones (clavicles) are also frequently enlarged on X-ray. Bone biopsy also reveals abscesses, known as sterile osteomyelitis.

SAPHO syndrome diagnosis

SAPHO syndrome is suspected when a patient presents with a pustular skin disease in association with rheumatic pain.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) shows inflammation of the bone marrow or joints at characteristic sites such as the collar bone, breast bone, pelvis, heel, and lower jaw.

The SAPHO syndrome was first proposed by Chamot, et al 15 in 1987 to describe a group of chronic aseptic inflammatory disorders involving the skin and joints. Currently, SAPHO syndrome has many diagnostic criteria, but the criteria proposed by Kahn and Khan in 1994 are most often mentioned, as confirmed by Marzano, et al 16.

In 1994, Kahn et al. 17 reported three diagnostic criteria that characterize SAPHO syndrome, which were modified in 2003 (see below) 18. In many cases, combinations of osteoarticular and skin manifestations lead to the diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome.

Diagnostic criteria for SAPHO syndrome 18:

Inclusion criteria

- Bone and/or joint involvement associated with palmoplantar pustulosis and psoriasis vulgaris, or hidradenitis suppurativa

- Bone and/or joint involvement associated with severe acne

- Isolated sterile hyperostosis/osteitis (adults). With the exception of Propionibacterium acnes.

- Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (children)

- Bone and/or joint involvement associated with chronic bowel diseases

Exclusion criteria

- Infectious osteitis

- Tumoral conditions of the bone

- Noninflammatory condensing lesions of the bone

The most common target site of osteoarticular lesions for SAPHO syndrome in adults is the anterior chest wall, in particular, the clavicles, sternum, and sternoclavicular joints, followed by the sacroiliac region and the spine 19. Mandibular involvement is relatively rare and has been reported to comprise 10% of this entity 20. Bone lesions tend to be osteolytic in early stages and osteosclerotic at later stages 19. Osteosclerotic manifestations include hyperostosis and osteitis, which are chronic inflammatory reactions involving both cortical and medullary bones.

On CT, hyperostosis appears as endosteal and periosteal reactions resulting in generalized cortical thickening and narrowing of the medullary canal. Osteitis appears as increased osteosclerosis involving the trabecular infrastructure of cancellous bone in response to the underlying inflammation 21. MRI provides better definition of the extent of the inflammatory process in relation to bone marrow edema and soft tissue swelling. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted or STIR images may show high signals on affected sites and are useful to differentiate active lesions from quiescent lesions. Erosions and osteosclerosis are not well depicted, which are well depicted on CT 21. Bone scintigraphy shows increased tracer uptake in the affected region. In addition, bone scintigraphy is useful because it frequently reveals clinically silent lesions. High tracer uptake in the sternocostoclavicular region yields the so-called “bull’s head sign,” with the body of the sternum representing the upper skull and the inflamed sternoclavicular joint with the adjacent clavicles forming the horns 22. A mandibular lesion also demonstrates the imaging findings described above. The mandibular lesion usually shows unilateral involvement at the body of the mandible 20. Although it is rare, extension to the temporomandibular joint evolves into ankylosis 23.

Some cases with imaging findings similar to mandibular involvement of SAPHO syndrome have been reported under various names, such as chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis, and juvenile mandibular chronic osteomyelitis (Garre’s osteomyelitis), and some of these cases are considered to be included in SAPHO syndrome 19. The differential diagnosis for imaging findings of mandibular lesion may include suppurative osteomyelitis, fibrous dysplasia, Paget’s disease, osseous neoplasms including osteoid osteoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, lymphoma, metastases, and Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis 19. It is difficult to differentiate SAPHO syndrome from suppurative osteomyelitis because of its nonspecific findings, such as bone marrow edema and periosteal reaction. Suei et al. reported that SAPHO syndrome revealed osteosclerotic and osteolytic patterns, solid periosteal reaction, external bone resorption, and bone enlargement, whereas suppurative osteomyelitis demonstrated an osteolytic pattern, a lamellated periosteal reaction, and cortical bone perforation 21.

The key to diagnose SAPHO syndrome is to depict both osteoarticular and skin manifestations; however, only the single bone may be symptomatic at disease onset and the skin manifestation does not always occur at the same time 24. Thus, making a diagnosis of SAPHO syndrome with the mandibular lesion alone as an initial presentation is difficult. In addition, patients may regard skin lesions and mandibular pain/swelling as irrelevant and sometimes skin lesions are hidden.

SAPHO syndrome treatment

SAPHO has no specific drug treatment. SAPHO syndrome can be a chronic condition but sometimes eventually heals on its own.

A rheumatologist may manage the joint symptoms, often prescribing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or sulfonamides such as sulfasalazine.

A dermatologist may use vitamin A derivatives (oral retinoids) to treat the acne (isotretinoin) and the palmoplantar pustulosis (acitretin).

Other drugs that may be used include:

- Colchicine

- Topical corticosteroids

- Systemic corticosteroids

- Methotrexate

- Calcitonin

- Bisphosphonates

- Infliximab

- Etanercept.

- Chamot AM, Benhamou CL, Kahn MF. et al. [Acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteitis syndrome. Results of a national survey. 85 cases]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 1987;54:187–96.[↩]

- Hedrich CM, Hofmann SR, Pablik J, Morbach H, Girschick HJ. Autoinflammatory bone disorders with special focus on chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Pediatric Rheumatol Online J 2013;11:47.[↩]

- Grateau G, Hentgen V, Stojanovic KS. et al. How should we approach classification of autoinflammatory diseases? Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:624–9.[↩]

- Stern SM, Ferguson PJ. Autoinflammatory bone diseases. Rheum Dis Clinics North Am 2013;39:735–49.[↩]

- Hukuda S., Minami M., Saito T., et al. Spondyloarthropathies in Japan: nationwide questionnaire survey performed by the Japan ankylosing spondylitis society. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2001;28(3):554–559.[↩]

- Roldán J. C., Terheyden H., Dunsche A., Kampen W. U., Schroeder J. O. Acne with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis involving the mandible as part of the SAPHO syndrome: case report. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2001;39(2):141–144. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0591[↩]

- Kikuchi T, Fujii H, Fujita A, Sugiyama T, Sugimoto H. Mandibular Osteitis Leading to the Diagnosis of SAPHO Syndrome. Case Rep Radiol. 2018;2018:9142362. Published 2018 Jun 13. doi:10.1155/2018/9142362 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6020456[↩]

- Magrey M., Khan M. A. New insights into synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2009;11(5):329–333. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0047-8.[↩]

- Ciccarelli F., De Martinis M., Ginaldi L. An update on autoinflammatory diseases. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;21(3):261–269. doi: 10.2174/09298673113206660303[↩][↩]

- Hayem G., Bouchaud-Chabot A., Benali K., et al. SAPHO syndrome: a long-term follow-up study of 120 cases. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1999;29(3):159–171. doi: 10.1016/S0049-0172(99)80027-4[↩][↩]

- Carneiro S., Sampaio-Barros P. D. SAPHO Syndrome. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 2013;39(2):401–418. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2013.02.009[↩][↩]

- Nguyen M. T., Borchers A., Selmi C., Naguwa S. M., Cheema G., Gershwin M. E. The SAPHO Syndrome. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012;42(3):254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.05.006[↩][↩]

- SAPHO syndrome. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sapho-syndrome[↩]

- Is SAPHO Syndrome Linked to PASH Syndrome and Hidradenitis Suppurativa by Nicastrin Mutation? A Case Report. CHENGRANG LI, HAOXIANG XU, BAOXI WANG. The Journal of Rheumatology Nov 2018, 45 (11) 1605-1607; DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.171007 http://www.jrheum.org/content/45/11/1605.3[↩]

- Chamot AM, Benhamou CL, Kahn MF, Beraneck L, Kaplan G, Prost A. [Acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteitis syndrome. Results of a national survey. 85 cases]. [Article in French] Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 1987;54:187–96.[↩]

- Marzano AV, Borghi A, Meroni PL, Cugno M. Pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic forms: evidence for a link with autoinflammation. Br J Dermatol 2016;175:882–91.[↩]

- Kahn M.-F., Khan M. A. The SAPHO syndrome. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 1994;8(2):333–362. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3579(94)80022-7[↩]

- Rukavina I. SAPHO syndrome: a review. Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics. 2015;9(1):19–27. doi: 10.1007/s11832-014-0627-7[↩][↩]

- Depasquale R., Kumar N., Lalam R. K., et al. SAPHO: what radiologists should know. Clinical Radiology. 2012;67(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.08.014[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Zemann W., Pau M., Feichtinger M., Ferra-Matschy B., Kaercher H. SAPHO syndrome with affection of the mandible: diagnosis, treatment, and review of literature. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2011;111(2):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.04.037[↩][↩]

- Earwaker J. W. S., Cotten A. SAPHO: Syndrome or concept? Imaging findings. Skeletal Radiology. 2003;32(6):311–327. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0629-x[↩][↩][↩]

- Freyschmidt J., Sternberg A. The bullhead sign: scintigraphic pattern of sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis and pustulotic arthroosteitis. European Radiology. 1998;8(5):807–812. doi: 10.1007/s003300050476[↩]

- Utumi E. R., Oliveira Sales M. A., Shinohara E. H., et al. SAPHO syndrome with temporomandibular joint ankylosis: clinical, radiological, histopathological, and therapeutical correlations. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2008;105(3):e67–e72. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.09.010[↩]

- Suei Y., Taguchi A., Tanimoto K. Diagnostic points and possible origin of osteomylitis in synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome: a radiographic study of 77 mandibular osteomyelitis cases. Rheumatology. 2003;42(11):1398–1403. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg396[↩]