What is Drinking Alcohol

Alcohol in the form of ethanol (ethyl alcohol) is found in alcoholic beverages, mouthwash, cooking extracts, some medications and certain household products. Ethanol (alcohol) is a central nervous system depressant that produces euphoria and behavioral excitation at low blood concentrations and acute intoxication (drowsiness, ataxia, slurred speech, stupor, and coma) at higher concentrations. The short-term effects of alcohol result from its actions on ligand-gated and voltage-gated ion channels 1. Prolonged alcohol consumption leads to the development of tolerance and physical dependence, which may result from compensatory functional changes in the same ion channels. Abrupt cessation of prolonged alcohol consumption unmasks these changes, leading to the alcohol withdrawal syndrome, which includes blackouts, tremors, muscular rigidity, delirium tremens, and seizures 2. Alcohol withdrawal seizures typically occur 6 to 48 hours after discontinuation of alcohol consumption and are usually generalized tonic–clonic seizures, although partial seizures also occur 3.

While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better 4, 5. Alcohol is a carcinogen associated with cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, colon, rectum, liver, and female breast, with breast cancer risk rising with less than one drink a day. Your whole body is impacted by alcohol use not just your liver, but also your brain, gut, pancreas, lungs, cardiovascular system, immune system, and more and may explain, for example, challenges in managing hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and recurrent lung infections.

Alcohol contributes to more than 200 health conditions including liver cirrhosis, cancers, and injuries and causes more than 3 million deaths each year globally (5.3% of all deaths worldwide) 6, 7. In the U.S., about 99,000 people die every year from alcohol-related causes 8, making alcohol one of the leading causes of preventable death 9, 10. More than half of the deaths result from chronic heavy alcohol consumption while the remainder result from acute injuries sustained while intoxicated 11.

The health risks of alcohol tend to be dose-dependent, and the likelihood of certain harms, such as cancer, begin at relatively low amounts 12. Even drinking within the U.S. Dietary Guidelines (see drinking level terms below), for example, increases the risk of breast cancer 13, 14. Additionally, earlier research suggested cardiovascular benefits, but newer, more rigorous studies are finding little or no protective effect of alcohol on cardiovascular or other outcomes 15, 16, 17, 18. In short, current research indicates there is no safe drinking level,11 underscoring the message to patients that “the less, the better” when it comes to alcohol.

The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines states that for adults who choose to drink alcohol, women should have 1 drink or less in a day and men should have 2 drinks or less in a day 19. These amounts are not intended as an average but rather a daily limit.

You are abusing alcohol when:

- You drink 7 drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion (for women).

- You drink more than 14 drinks per week or more than 4 drinks per occasion (for men).

- You have more than 7 drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion (for men and women older than 65).

- Consuming these amounts of alcohol harms your health, relationships, work, and/or causes legal problems.

How does my body process alcohol?

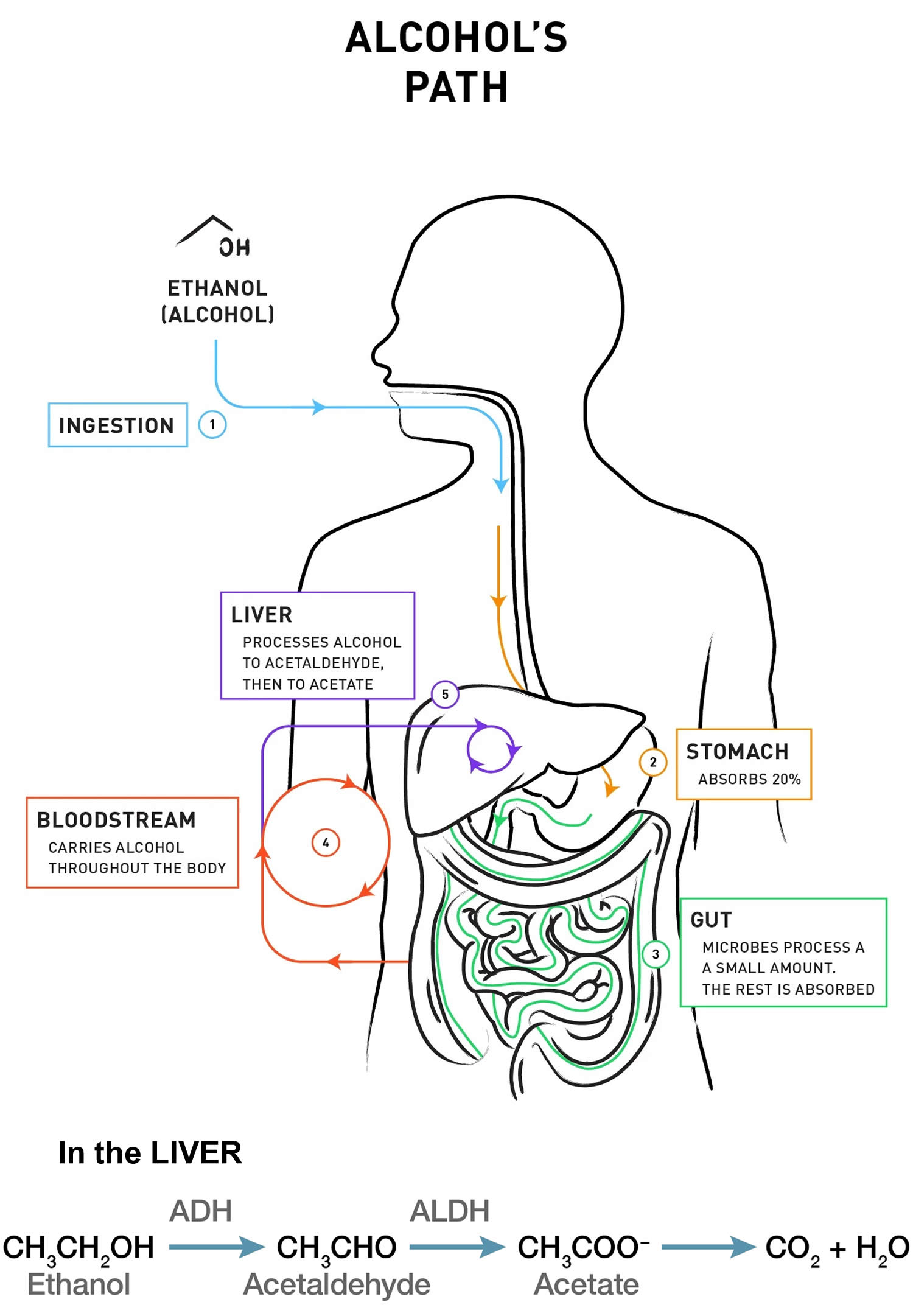

When alcohol is consumed, it passes from your stomach and intestines into your bloodstream, where it distributes itself evenly throughout all the water in your body’s tissues and fluids. Drinking alcohol on an empty stomach increases the rate of absorption, resulting in higher blood alcohol level, compared to drinking on a full stomach. In either case, however, alcohol is still absorbed into the bloodstream at a much faster rate than it is metabolized. Thus, your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) builds when you have additional drinks before prior drinks are metabolized.

Your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is largely determined by how much and how quickly you drink alcohol as well as by your body’s rates of alcohol absorption, distribution, and metabolism. Binge drinking is defined as reaching a BAC of 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or higher. A typical adult reaches this BAC after consuming 4 or more drinks (women) or 5 or more drinks (men), in about 2 hours.

Your body begins to metabolize alcohol within seconds after ingestion and proceeds at a steady rate, regardless of how much alcohol a person drinks or of attempts to sober up with caffeine or by other means. Most of the alcohol is broken down in your liver by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) transforms ethanol, the type of alcohol in alcohol beverages, into acetaldehyde, a toxic, carcinogenic compound. Generally, acetaldehyde is quickly broken down to a less toxic compound, acetate, by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) (also called aldehyde dehydrogenase). Acetate then is broken down, mainly in tissues other than the liver, into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O), which are easily eliminated. To a lesser degree, other enzymes (CYP2E1 and catalase) also break down alcohol to acetaldehyde 20.

Although the rate of metabolism is steady in any given person, it varies widely among individuals depending on factors including liver size and body mass, as well as genetics. There are multiple ADH and ALDH enzymes that are encoded by different genes 20. These genetic variants have been shown to influence a person’s drinking levels and, consequently, the risk of developing alcohol abuse or dependence 21. Studies have shown that people carrying certain ADH and ALDH alleles (one of two or more variants of a gene) are at significantly reduced risk of becoming alcohol dependent. In fact, these associations are the strongest and most widely reproduced associations of any gene with the risk of alcoholism. Some people of Asian descent, for example, carry variations of the genes for alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) or acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) that cause acetaldehyde (a toxic carcinogenic compound) to build up when alcohol is consumed, which in turn produces a flushing reaction and increases the risk of cancer risk 22, 23, 24. 20% of Chinese and Japanese cannot drink alcohol because of an inherited deficiency of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 25.

Figure 2. How the body processes alcohol

Do you have a drinking problem?

While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better 4, 5. The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines states that for adults who choose to drink alcohol, women should have 1 drink or less in a day and men should have 2 drinks or less in a day 19. These amounts are not intended as an average but rather a daily limit. Many people with alcohol problems cannot tell when their drinking is out of control. It is important to be aware of how much you are drinking. You should also know how your alcohol use may affect your life and those around you.

Many patients may think that heavy drinking is not a concern because they can “hold their liquor.” However, having an innate “low level of response” or “high tolerance” to alcohol is a reason for caution, as people with this trait tend to drink more and thus have an increased risk for alcohol-related problems including alcohol use disorder 26. People who drink within the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, too, may be unaware that even if they don’t feel a “buzz,” driving can be impaired 27.

Doctors consider your drinking medically unsafe when you drink:

- Many times a month, or even many times a week

- 3 to 4 drinks (or more) in 1 day

- 5 or more drinks on one occasion monthly, or even weekly

Twelve questions to ask if you think you may have a drinking problem

- Have you ever decided to stop drinking for a week or so, but only lasted for a couple of days? (Yes or No)

- Do you wish people would mind their own business about your drinking– stop telling you what to do? (Yes or No)

- Have you ever switched from one kind of drink to another in the hope that this would keep you from getting drunk? (Yes or No)

- Have you had to have a drink upon awakening during the past year? (Yes or No)

- Do you envy people who can drink without getting into trouble? (Yes or No)

- Have you had problems connected with drinking during the past year? (Yes or No)

- Has your drinking caused trouble at home? (Yes or No)

- Do you ever try to get “extra” drinks at a party because you do not get enough? (Yes or No)

- Do you tell yourself you can stop drinking any time you want to, even though you keep getting drunk when you don’t mean to? (Yes or No)

- Have you missed days of work or school because of drinking? (Yes or No)

- Do you have “blackouts”? (Yes or No) (Alcohol-related blackouts are gaps in a person’s memory for events that occurred while they were intoxicated. These gaps happen when a person drinks enough alcohol to temporarily block the transfer of memories from short-term to long-term storage, known as memory consolidation, in a brain area called the hippocampus.)

- Have you ever felt that your life would be better if you did not drink? (Yes or No)

If you answer YES 4 or more times – you are probably in trouble with alcohol.

However severe your drinking problem may seem, most people with alcohol use disorder can benefit from treatment. Unfortunately, less than 10 percent of them receive any treatment.

Ultimately, receiving treatment can improve your chances of success in overcoming alcohol use disorder.

Talk with your doctor to determine the best course of action for you.

What are the dangers of too much alcohol?

Too much alcohol is dangerous. Heavy drinking can increase the risk of certain cancers. It may lead to liver diseases, such as fatty liver disease and cirrhosis. It can also cause damage to the brain and other organs. Drinking during pregnancy can harm your baby. Alcohol also increases the risk of death from car crashes, injuries, homicide, and suicide.

Alcohol use is the fourth leading cause of preventable death in the United States (after smoking, high blood pressure, and obesity). According to a 2018 report from the WHO, in 2016 the harmful use of alcohol resulted in about 3 million deaths, or 5.3% of all deaths around the world, with most of these occurring among men 6. An average of 6 people die of alcohol poisoning each day in the US from 2010 to 2012 28. Alcohol poisoning is caused by drinking large quantities of alcohol in a short period of time. Very high levels of alcohol in the body can shutdown critical areas of the brain that control breathing, heart rate, and body temperature, resulting in death. Alcohol poisoning deaths affect people of all ages but are most common among middle-aged adults and men.

76% of alcohol poisoning deaths are among adults ages 35 to 64 28.

About 76% of those who die from alcohol poisoning are men 28.

The economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in 2010 were estimated at $249 billion, or $2.05 a drink 29.

Alcohol poisoning deaths

- Most people who die are 35-64 years old.

- Most people who die are men.

- Most alcohol poisoning deaths are among non- Hispanic whites. Although a smaller share of the US population, American Indians/Alaska Natives have the most alcohol poisoning deaths per million people of any of the races.

- Alaska has the most alcohol poisoning deaths per million people, while Alabama has the least.

- Alcohol dependence (alcoholism) was identified as a factor in 30% of alcohol poisoning deaths.

Binge drinking can lead to death from alcohol poisoning

- Binge drinking (4 or more drinks for women or 5 or more drinks for men in a short period of time) typically leads to a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) that exceeds 0.08 g/dL, the legal limit for driving in all states.

- US adults who binge drink consume an average of about 8 drinks per binge, which can result in even higher levels of alcohol in the body.

- The more you drink the greater your risk of death.

An estimated 88,000 people (approximately 62,000 men and 26,000 women) die from alcohol-related causes annually, making alcohol the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States 30. Alcohol deaths accounted for 1 in 10 deaths among working-age adults aged 20–64 years 31. Excessive alcohol use shortened the lives of those who died by about 30 years. These deaths were due to health effects from drinking too much over time, such as breast cancer, liver disease, and heart disease, and health effects from consuming a large amount of alcohol in a short period of time, such as violence, alcohol poisoning, and motor vehicle crashes.

In 2014, alcohol-impaired driving fatalities accounted for 9,967 deaths (31 percent of overall driving fatalities) 32.

Figure 1. Alcohol Poisoning Deaths

[Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 28]What counts as a standard drink?

In the United States, a “standard drink” or “alcoholic drink equivalent” is any drink containing 14 grams, or about 0.6 fluid ounces, of “pure” ethanol. One alcoholic drink equals one 12-ounce (oz), or 355 milliliters (mL), can or bottle of beer (with 5% alcohol by volume or alc/vol), a 5-ounce (148 mL) glass of wine (with 12% alc/vol), 1 wine cooler, 1 cocktail, 1 shot of hard liquor; or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (such as whiskey, rum, or tequila) (with 40% alc/vol) 33.

Knowing how much alcohol constitutes a “standard” drink can help you determine how much you are drinking and understand the risks. One standard drink contains about 0.6 fluid ounces or 14 grams of pure alcohol.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines one standard drink as any one of these:

- 12 ounces (355 milliliters) of regular beer (about 5 percent alcohol)

- 8 to 9 ounces (237 to 266 milliliters) of malt liquor (about 7 percent alcohol)

- 5 ounces (148 milliliters) of unfortified wine (about 12 percent alcohol)

- 1.5 ounces (44 milliliters) of 80-proof hard liquor (about 40 percent alcohol)

If you want to know the alcohol content of a canned or bottled beverage, start by checking the label. Not all beverages are required to list the alcohol content, so you may need to search online for a reliable source of information, such as the bottler’s Web site. For fact sheets about how to read wine, malt beverage, and distilled spirits labels, visit the consumer corner of the U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau 34.

Although the “standard” drink amounts are helpful for following health guidelines, they may not reflect customary serving sizes. In addition, while the alcohol concentrations listed are “typical,” there is considerable variability in alcohol content within each type of beverage (e.g., beer, wine, distilled spirits). If you want to know how much alcohol is in a cocktail or a beverage container, try the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking – Alcohol calculators 35 or go here https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/Tools/Calculators/Default.aspx.

Footnotes: The sample standard drinks above are just starting points for comparison, because actual alcohol content and customary serving sizes can vary greatly both across and within types of beverages. For example:

- Beer: The most popular type of beer is light beer, which may be light in calories, but not necessarily in alcohol. The mean alc/vol for light beers is 4.3%, almost as much as a regular beer with 5% alc/vol.4 On average, craft beers have more than 5% alc/vol and flavored malt beverages, such as hard seltzers, more than 6% alc/vol.4 Some craft beers and flavored malt beverages have in the range of 8-9% alc/vol. Advise patients to check container labels for the alcohol content and adjust their intake accordingly.

- Wine: The largest category of wine is table wine. On average, table wines contain about 12% alc/vol4 and can range from about 5% to 16%. Larger wine glasses can encourage larger pours. People are often unaware that a 25-ounce (750ml) bottle of table wine with 12% alc/vol contains five standard drinks, and one with 14% alc/vol holds nearly six.

- Cocktails: Recipes for cocktails often exceed one standard drink’s worth of alcohol. The cocktail content calculator on Rethinking Drinking shows the alcohol content in sample cocktails.

How many drinks are in common containers?

In the United States, a “standard” drink is any drink that contains about 0.6 fluid ounces or 14 grams of “pure” alcohol. Below is the approximate number of standard drinks in different sized containers of

Table 1. How many drinks are in common containers

| Regular beer (5% alc/vol) | Malt liquor (7% alc/vol) | Table wine (12% alc/vol) | 80-proof distilled spirits (40% alc/vol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 fl oz = 1 16 fl oz = 1⅓ 22 fl oz = 2 40 fl oz = 3⅓ | 12 fl oz = 1½ 16 fl oz = 2 22 fl oz = 2½ 40 fl oz = 4½ | 750 ml (a regular wine bottle) = 5 | a shot (1.5-oz glass/50-ml bottle) = 1 a mixed drink or cocktail = 1 or more 200 ml (a “half pint”) = 4½ 375 ml (a “pint” or “half bottle”) = 8½ 750 ml (a “fifth”) = 17 |

Footnote: Although the “standard” drink amounts are helpful for following health guidelines, they may not reflect customary serving sizes. In addition, while the alcohol concentrations listed are “typical,” there is considerable variability in alcohol content within each type of beverage (e.g., beer, wine, distilled spirits).

Do you drink cocktails or a beverage not listed above ? If you’re curious and willing to do a little research on your drink’s alcohol content, you can use Rethinking Drinking’s calculators (https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/Tools/Calculators/Default.aspx) to estimate the number of standard drinks per cocktail or container.

[Source 36 ]Levels of alcohol use

There are four levels of alcohol use:

- Social drinking: There is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone. According to the “Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025” 19, adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men (less than 14 drinks per week for men) and 1 drink or less in a day for women (less than 7 drinks per week for women), when alcohol is consumed. Drinking less is better for health than drinking more.

- At risk consumption: the level of drinking begins to pose a health risk. Frequent heavy drinking raises the risk for both acute harms, such as falls and medication interactions, and for chronic consequences, such as alcohol use disorder and dose-dependent increases in liver disease, heart disease and cancers 37, 38, 39.

- For men, consuming more than 5 drinks on any day or more than 15 drinks per week

- For women, consuming more than 4 drinks on any day or more than 8 drinks per week

- Binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month

- Heavy drinking thresholds for women are lower than men because after consumption, alcohol distributes itself evenly in body water, and pound for pound, women have proportionally less water in their bodies than men do. This means that after a woman and a man of the same weight drink the same amount of alcohol, the woman’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) will tend to be higher, putting her at greater risk for harm.

- Problem drinking: drinking causes serious problems to you, your family, your work and society in general

- Alcohol dependence and addiction:

- periodic or chronic intoxication

- uncontrollable craving for drink when sober

- tolerance to the effects of alcohol

- psychological and/or physical dependence

How much is too much?

How much alcohol is too much? It could mean drinking too much at one time, drinking too often, or both. It’s important to be aware of how much you are drinking, whether your drinking pattern is risky, the harm that some drinking patterns can cause, and ways to reduce your risks.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans defines moderate drinking as up to 1 drink per day for women and up to 2 drinks per day for men 19. In addition, the Dietary Guidelines do not recommend that individuals who do not drink alcohol start drinking for any reason.

You are drinking too much if:

- On any day in the past year, For MEN: you drink more than 4 “standard” drinks per day and For WOMEN: you drink more than 3 “standard” drinks per day.

- On average, you drink alcohol more than 2 days per week.

- On a typical drinking day, you drink more than 4 standard drinks (for Men) or more than 3 standard drinks (for Women).

Figure 2. U.S. Adults Drinking Patterns

[Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking 40 ]You have had more “heavy drinking days” in the past year than 7 in 10 U.S. adults . Although your weekly average is typically within low-risk limits, once or twice a week you have more than the single-day limit of 4 drinks for men. You may be surprised that the majority of U.S. adults never exceed the low-risk drinking limits.

Your particular risk depends on how much, how quickly, and how often you drink. According to the National Institutes of Health survey, about 1 in 3 people in your drinking pattern group has an alcohol use disorder. In addition, just a single episode of drinking too much, too quickly, can lead to a serious injury.

Excessive drinking includes binge drinking, heavy drinking, and any drinking by pregnant women or people younger than age 21.

- Binge drinking, the most common form of excessive drinking, is defined as consuming

+ For women, 4 or more drinks during a single occasion.

+ For men, 5 or more drinks during a single occasion. - Heavy drinking is defined as consuming

+For women, 8 or more drinks per week.

+ For men, 15 or more drinks per week.

Most people who drink excessively are not alcoholics or alcohol dependent 41

You can reduce your risks. Research shows that people who stay within both the single-day and weekly limits have the lowest rates of alcohol-related problems. It’s safest to quit, however, if you already have signs of a problem.

Figure 3. “Low-Risk” Drinking Patterns

[Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking 42]“Low risk” is not “no risk.” Even within these limits, alcohol can cause problems if people drink too quickly, have health problems, or are older (both men and women over 65 are generally advised to have no more than 3 drinks on any day and 7 per week) 42. Based on your health and how alcohol affects you, you may need to drink less or not at all.

Research demonstrates “low-risk” drinking levels for men are no more than 4 drinks on any single day AND no more than 14 drinks per week 43. For women, “low-risk” drinking levels are no more than three drinks on any single day AND no more than seven drinks per week 43. To stay low-risk, you must keep within both the single-day and weekly limits.

Even within these limits, you can have problems if you drink too quickly, have health conditions, or are over age 65. Older adults should have no more than three drinks on any day and no more than seven drinks per week.

When is “low-risk” drinking still too much?

It’s safest to avoid alcohol altogether if you are:

- Taking medications that interact with alcohol

- Managing a medical condition that can be made worse by drinking

- Underage

- Planning to drive a vehicle or operate machinery

- Pregnant or trying to become pregnant

- Recovering from alcoholism or are unable to control the amount they drink.

Research shows that women start to have alcohol-related problems at lower drinking levels than men do 40. One reason is that, on average, women weigh less than men. In addition, alcohol disperses in body water, and pound for pound, women have less water in their bodies than men do. So after a man and woman of the same weight drink the same amount of alcohol, the woman’s blood alcohol concentration will tend to be higher, putting her at greater risk for harm.

How can you reduce your risks of alcohol use disorder?

Options for reducing alcohol-related risks include:

- Staying within low-risk drinking limits.

- Taking steps to be safe when you drink.

- Quitting drinking altogether.

For some people, staying within low-risk limits will be sufficient, whereas for others, it’s best to quit.

If you sometimes drink more than the low-risk limits, but don’t feel ready to make a change, see Pros and cons and Ready… or not. Don’t wait for an injury or a crisis, however. When it comes to changing risky drinking, sooner is better than later.

What’s “at-risk” or “heavy” drinking?

For healthy adults in general, drinking more than these single-day or weekly limits is considered “at-risk” or “heavy” drinking:

- Men: More than 4 drinks on any day or 14 per week.

- Women: More than 3 drinks on any day or 7 per week.

About 1 in 4 people who exceed these limits already has an alcohol use disorder, and the rest are at greater risk for developing these and other problems. Again, individual risks vary. People can have problems drinking less than these amounts, particularly if they drink too quickly 44.

In short, the more drinks on any day and the more heavy drinking days over time, the greater the risk—not only for an alcohol use disorder, but also for other health and personal problems.

Too much + too often = too risky

It makes a difference both how much you drink on any day and how often you have a “heavy drinking day,” that is, more than 4 drinks on any day for men or more than 3 drinks for women.

What is binge drinking?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking is drinking so much at once that your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) level is 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or more. For a man, this usually happens after having 5 or more drinks within about 2 hours. For a woman, it is after about 4 or more drinks within about 2 hours 45. Not everyone who binge drinks has an alcohol use disorder, but they are at higher risk for getting one.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which conducts the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health, defines binge drinking as 5 or more alcoholic drinks for males or 4 or more alcoholic drinks for females on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past month.

Binge drinking occurs in the majority of adolescents who drink 46, in half of adults who drink 46 and in 1 in 10 adults over age 65 47 and is increasing among women 48, 49.

Binge drinking causes more than half of the alcohol-related deaths in the U.S. 46. Binge drinking increases the risk of falls, burns, car crashes, memory blackouts, medication interactions, assaults, drownings, and overdose deaths 46.

Alcohol use disorder

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) also called alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence syndrome, is an impaired ability to stop or control alcohol use despite adverse social, occupational, or health consequences 50. Alcohol use disorder encompasses the conditions that some people refer to as alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, alcohol addiction, and the colloquial term, alcoholism. Alcohol use disorder can be mild, moderate, or severe. Severe alcohol use disorder is sometimes called alcoholism or alcohol dependence.

Alcohol use disorder is a medical condition in which you:

- Drink alcohol compulsively

- Can’t control how much you drink

- Feel anxious, irritable, and/or stressed when you are not drinking

An alcohol use disorder can range from mild to severe, depending on your symptoms.

With alcohol use disorder, you are not physically dependent, but you still have a serious problem. The drinking may cause problems at home, work, or school. Alcohol use disorder may cause you to put yourself in dangerous situations, or lead to legal or social problems.

Another common problem is binge drinking. Binge drinking is drinking about five or more drinks in two hours for men. For women, it is about four or more drinks in two hours.

Too much alcohol is dangerous. Heavy drinking can increase your risk of getting certain cancers. Too much alcohol can cause damage to the liver, brain, and other organs. Drinking during pregnancy can harm your baby. Alcohol also increases the risk of death from car crashes, injuries, homicide, and suicide.

Alcoholism or alcohol dependence, is a disease that causes:

- Craving – a strong need to drink

- Loss of control – not being able to stop drinking once you’ve started

- Physical dependence – withdrawal symptoms

- Tolerance – the need to drink more alcohol to feel the same effect

Alcohol use disorder is considered a brain disorder characterized by compulsive alcohol use, loss of control over alcohol intake, and a negative emotional state when not using 51. Lasting changes in the brain caused by alcohol misuse perpetuate alcohol use disorder and make individuals vulnerable to relapse. The good news is that no matter how severe the problem may seem, evidence-based treatment with behavioral therapies, mutual-support groups, and/or medications can help people with alcohol use disorder achieve and maintain recovery. According to a National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 14.1 million adults ages 18 and older (5.6 percent of this age group) had alcohol use disorder in 2019 52, 53. Among youth, an estimated 414,000 adolescents ages 12–17 (1.7 percent of this age group) had alcohol use disorder during this timeframe.

An estimated 16 million people in the United States have alcohol use disorder 51. This means that their drinking causes distress and harm. It includes alcoholism and alcohol abuse. Approximately 6.2 percent or 15.1 million adults in the United States ages 18 and older had alcohol use disorder in 2015. This includes 9.8 million men and 5.3 million women. Adolescents can be diagnosed with alcohol use disorder as well, and in 2015, an estimated 623,000 adolescents ages 12–17 had alcohol use disorder 51.

To be diagnosed with alcohol use disorder, individuals must meet certain criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), under DSM–5, the current version of the DSM, anyone meeting any two of the 11 criteria during the same 12-month period receives a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder. The severity of alcohol use disorder—mild, moderate, or severe—is based on the number of criteria met.

To assess whether you or loved one may have alcohol use disorder, here are some questions to ask.

Alcohol use disorder is diagnosed when a person answers “yes” to two or more of the questions below.

In the past year, have you:

- Ended up drinking more or for a longer time than you had planned to?

- Wanted to cut down or stop drinking, or tried to, but couldn’t?

- Spent a lot of your time drinking, or recovering from drinking?

- Needed a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

- Felt a strong need to drink?

- Felt annoyed by criticism of your drinking?

- Had guilty feelings about drinking?

- Found that drinking – or being sick from drinking – often interfered with your family life, job, or school?

- Kept drinking even though it was causing trouble with your family or friends?

- Given up or cut back on activities that you enjoyed just so you could drink?

- Gotten into dangerous situations while drinking or after drinking? Some examples are driving drunk and having unsafe sex.

- Kept drinking even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious? Or when it was adding to another health problem?

- Had to drink more and more to feel the effects of the alcohol?

- Had withdrawal symptoms when the alcohol was wearing off? They include trouble sleeping, shakiness, irritability, anxiety, depression, restlessness, nausea, and sweating. In severe cases, you could have a fever, seizures, or hallucinations.

If you have any of these symptoms, your drinking may already be a cause for concern. The more symptoms you have, the more urgent the need for change. A health professional can conduct a formal assessment of your symptoms to see if alcohol use disorder is present.

However severe the problem may seem, most people with alcohol use disorder can benefit from treatment. Unfortunately, less than 10 percent of them receive any treatment.

Ultimately, receiving treatment can improve an individual’s chances of success in overcoming alcohol use disorder.

Talk with your doctor to determine the best course of action for you.

If you feel that you sometimes drink too much alcohol, or your drinking is causing problems, or your family is concerned about your drinking, talk with your doctor. Other ways to get help include talking with a mental health professional or seeking help from a support group such as Alcoholics Anonymous or a similar type of self-help group.

Because denial is common, you may not feel like you have a problem with drinking. You might not recognize how much you drink or how many problems in your life are related to alcohol use. Listen to relatives, friends or co-workers when they ask you to examine your drinking habits or to seek help. Consider talking with someone who has had a problem drinking, but has stopped.

If your loved one needs help

Many people with alcohol use disorder hesitate to get treatment because they don’t recognize they have a problem. An intervention from loved ones can help some people recognize and accept that they need professional help. If you’re concerned about someone who drinks too much, ask a professional experienced in alcohol treatment for advice on how to approach that person.

What cause alcohol use disorder?

The cause of alcohol use disorder is not well understood; however, several factors are thought to contribute to its development. These include the home environment, peer interactions, genetic factors, level of cognitive functioning, and certain existing personality disorders 54.Personality disorders associated with the development of an alcohol use disorder include disinhibition and impulsivity-type disorders, as well as depressive and socialization-related disorders 55.

Almost half of the people with any substance abuse problem, including alcohol use disorder, also had a co-existing mental illness 56, 57. Overall, alcohol use disorder tends to be more common in individuals with less education and low income.

Multiple theories have been suggested as to why some people develop alcohol use disorders. Some of the more evidence-supported theories include positive-effect regulation, negative-effect regulation, pharmacological vulnerability, and deviance proneness. Positive-effect regulation results in drinking for positive rewards (such as feelings of euphoria). Negative-effect regulation is seen when one drinks to cope with feelings of a negative nature, such as depression, anxiety, or feelings of worthlessness. Pharmacological vulnerability makes a note of an individual’s varied response to both acute and chronic effects of alcohol intake and the individual differences in the body’s ability to metabolize the alcohol. Deviance proneness speaks more to an individual’s tendency towards deviant behavior established during childhood, often due to a deficiency in socialization at an early age.

Some of the genes suspected in alcohol use disorder include GABRG2 and GABRA2, COMT Val 158Met, DRD2 Taq1A, and KIAA0040.

Risk factors for developing alcohol-use disorder

There is no single factor that accounts for the variation in individual risk of developing alcohol-use disorders. Alcohol use may begin in the teens, but alcohol use disorder occurs more frequently in the 20s and 30s, though it can start at any age. The evidence suggests that harmful alcohol use and alcohol dependence have a wide range of causal factors

- Family history of alcohol abuse. The risk of alcohol use disorder is higher for people who have a parent or other close relative who has problems with alcohol. This may be influenced by genetic factors.

- offspring of parents with alcohol dependence are four times more likely to develop alcohol dependence

- genetic studies (particularly those in twins) has clearly demonstrated a genetic component to the risk of alcohol dependence

- a meta-analysis of 9,897 twin pairs from Australian and US studies found the heritability of alcohol dependence to be in excess of 50%

- Psychological factors

- psychiatric comorbidity particularly depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BPD), anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis and drug misuse. It’s common for people with a mental health disorder such as anxiety, depression, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder to have problems with alcohol or other substances.

- Stress, adverse life events and abuse

- Sex: men are twice as likely to be problem drinkers

- Occupation:

- publicans and brewers have an increased access to drink and are at a higher risk

- heavy drinking is seen as the norm in some jobs e.g. sailors

- Homelessness:

- a third of homeless people have a drink problem

- Steady drinking over time. Drinking too much on a regular basis for an extended period or binge drinking on a regular basis can lead to alcohol-related problems or alcohol use disorder.

- Started drinking at an early age. People who begin drinking — especially binge drinking — at an early age are at a higher risk of alcohol use disorder.

- History of trauma. People with a history of emotional or other trauma are at increased risk of alcohol use disorder.

- Having bariatric surgery (weight-loss surgery — involves making changes to your digestive system to help you lose weight). Some research studies indicate that having bariatric surgery may increase the risk of developing alcohol use disorder or of relapsing after recovering from alcohol use disorder.

- Social and cultural factors. Having friends or a close partner who drinks regularly could increase your risk of alcohol use disorder. The glamorous way that drinking is sometimes portrayed in the media also may send the message that it’s OK to drink too much. For young people, the influence of parents, peers and other role models can impact risk.

Alcohol use disorder prevention

Early intervention can prevent alcohol-related problems in teens. If you have a teenager, be alert to signs and symptoms that may indicate a problem with alcohol:

- Loss of interest in activities and hobbies and in personal appearance

- Red eyes, slurred speech, problems with coordination and memory lapses

- Difficulties or changes in relationships with friends, such as joining a new crowd

- Declining grades and problems in school

- Frequent mood changes and defensive behavior

You can help prevent teenage alcohol use:

- Set a good example with your own alcohol use.

- Talk openly with your child, spend quality time together and become actively involved in your child’s life.

- Let your child know what behavior you expect — and what the consequences will be if he or she doesn’t follow the rules.

Alcohol use disorder symptoms

A few mild symptoms — which you might not see as trouble signs — can signal the start of a drinking problem. It helps to know the signs so you can make a change early. If heavy drinking continues, then over time, the number and severity of symptoms can grow and add up to “alcohol use disorder.” Doctors diagnose alcohol use disorder when a patient’s drinking causes distress or harm. See if you recognize any of these symptoms in yourself. And don’t worry — even if you have symptoms, you can take steps to reduce your risks.

Alcohol use disorder can be mild, moderate or severe, based on the number of symptoms you experience.

Alcohol use disorder signs and symptoms may include:

- Being unable to limit the amount of alcohol you drink

- Wanting to cut down on how much you drink or making unsuccessful attempts to do so

- Spending a lot of time drinking, getting alcohol or recovering from alcohol use

- Feeling a strong craving or urge to drink alcohol

- Failing to fulfill major obligations at work, school or home due to repeated alcohol use

- Continuing to drink alcohol even though you know it’s causing physical, social or interpersonal problems

- Giving up or reducing social and work activities and hobbies

- Using alcohol in situations where it’s not safe, such as when driving or swimming

- Developing a tolerance to alcohol so you need more to feel its effect or you have a reduced effect from the same amount

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms — such as nausea, sweating and shaking — when you don’t drink, or drinking to avoid these symptoms

Alcohol use disorder can include periods of alcohol intoxication and symptoms of withdrawal.

- Alcohol intoxication results as the amount of alcohol in your bloodstream increases. The higher the blood alcohol concentration is, the more impaired you become. Alcohol intoxication causes behavior problems and mental changes. These may include inappropriate behavior, unstable moods, impaired judgment, slurred speech, impaired attention or memory, and poor coordination. You can also have periods called “blackouts,” where you don’t remember events. Very high blood alcohol levels can lead to coma or even death.

- Alcohol withdrawal can occur when alcohol use has been heavy and prolonged and is then stopped or greatly reduced. It can occur within several hours to four or five days later. Signs and symptoms include sweating, rapid heartbeat, hand tremors, problems sleeping, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, restlessness and agitation, anxiety, and occasionally seizures. Symptoms can be severe enough to impair your ability to function at work or in social situations.

The more symptoms you have, the more serious the problem is. If you think you might have an alcohol use disorder, see your health care provider for an evaluation. Your provider can help make a treatment plan, prescribe medicines, and if needed, give you treatment referrals.

People with alcohol use disorder may also report frequent falls, blackout spells, unsteadiness, or visual disturbances 54. They may report seizures if they went a few days without drinking, or tremors, confusion, emotional disturbances, and frequent job changes. They may also report social issues, such as job termination, separation/divorce, estrangement from family, or loss of home. They may also report sleep disturbances.

People with alcohol use disorder may have hypertension (high blood pressure) or insomnia (trouble falling and staying asleep) initially. In later stages, the patient may complain of nausea or vomiting, hematemesis (vomiting blood), bloated abdomen, epigastric pain, weight loss, jaundice, or other symptoms or signs suggestive of liver dysfunction. They may be asymptomatic early on.

People with alcohol use disorder may exhibit signs of cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia (impaired balance or coordination) or difficulty with fine motor skills, on exam. They may exhibit slurred speech, tachycardia (fast heart rate), memory impairment, nystagmus (involuntary eye movement which may cause the eye to rapidly move from side to side, up and down or in a circle), disinhibited behavior, or hypotension (low blood pressure). People with alcohol use disorder may present with tremors, confusion/mental status changes, asterixis, reddsih palms, jaundice, ascites, or other signs of advanced liver disease. There may also be spider angiomata, hepatomegaly/splenomegaly (early; liver becomes cirrhotic and shrunken in advanced disease). They may develop bleeding disorders, anemia, gastritis/ulcers, or pancreatitis as complications of alcohol use. Labs will reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, hyponatremia, hyperammonemia, elevated ammonia levels, or decreased B12/folate levels as the advanced liver disease develops.

Alcohol use disorder complications

Alcohol depresses your central nervous system. In some people, the initial reaction may be stimulation. But as you continue to drink, you become sedated.

Too much alcohol affects your speech, muscle coordination and vital centers of your brain. A heavy drinking binge may even cause a life-threatening coma or death. This is of particular concern when you’re taking certain medications that also depress the brain’s function.

Alcohol use disorder impact on your safety

Excessive drinking can reduce your judgment skills and lower inhibitions, leading to poor choices and dangerous situations or behaviors, including:

- Motor vehicle accidents and other types of accidental injury, such as drowning

- Relationship problems

- Poor performance at work or school

- Increased likelihood of committing violent crimes or being the victim of a crime

- Legal problems or problems with employment or finances

- Problems with other substance use

- Engaging in risky, unprotected sex, or experiencing sexual abuse or date rape

- Increased risk of attempted or completed suicide

Alcohol use disorder impact on your health

Drinking too much alcohol on a single occasion or over time can cause health problems, including:

- Liver disease. Heavy drinking can cause increased fat in the liver (hepatic steatosis), inflammation of the liver (alcoholic hepatitis), and over time, irreversible destruction and scarring of liver tissue (cirrhosis).

- Digestive problems. Heavy drinking can result in inflammation of the stomach lining (gastritis), as well as stomach and esophageal ulcers. It can also interfere with absorption of B vitamins and other nutrients. Heavy drinking can damage your pancreas or lead to inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

- Heart problems. Excessive drinking can lead to high blood pressure and increases your risk of an enlarged heart, heart failure or stroke. Even a single binge can cause a serious heart arrhythmia called atrial fibrillation.

- Diabetes complications. Alcohol interferes with the release of glucose from your liver and can increase the risk of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia). This is dangerous if you have diabetes and are already taking insulin to lower your blood sugar level.

- Sexual function and menstruation issues. Excessive drinking can cause erectile dysfunction in men. In women, it can interrupt menstruation.

- Eye problems. Over time, heavy drinking can cause involuntary rapid eye movement (nystagmus) as well as weakness and paralysis of your eye muscles due to a deficiency of vitamin B-1 (thiamin). A thiamin deficiency can also be associated with other brain changes, such as irreversible dementia, if not promptly treated.

- Birth defects. Alcohol use during pregnancy may cause miscarriage. It may also cause fetal alcohol syndrome, resulting in giving birth to a child who has physical and developmental problems that last a lifetime.

- Bone damage. Alcohol may interfere with the production of new bone. This bone loss can lead to thinning bones (osteoporosis) and an increased risk of fractures. Alcohol can also damage bone marrow, which makes blood cells. This can cause a low platelet count, which may result in bruising and bleeding.

- Neurological complications. Excessive drinking can affect your nervous system, causing numbness and pain in your hands and feet, disordered thinking, dementia, and short-term memory loss.

- Weakened immune system. Excessive alcohol use can make it harder for your body to resist disease, increasing your risk of various illnesses, especially pneumonia.

- Increased risk of cancer. Long-term, excessive alcohol use has been linked to a higher risk of many cancers, including mouth, throat, liver, esophagus, colon and breast cancers. Even moderate drinking can increase the risk of breast cancer.

- Medication and alcohol interactions. Some medications interact with alcohol, increasing its toxic effects. Drinking while taking these medications can either increase or decrease their effectiveness, or make them dangerous.

Alcohol use disorder diagnosis

You’re likely to start by seeing your doctor. If your doctor suspects you have a problem with alcohol, he or she may refer you to a mental health professional.

To assess your problem with alcohol, your doctor will likely:

- Ask you several questions related to your drinking habits. The doctor may ask for permission to speak with family members or friends. However, confidentiality laws prevent your doctor from giving out any information about you without your consent.

- Perform a physical exam. Your doctor may do a physical exam and ask questions about your health. There are many physical signs that indicate complications of alcohol use.

- Lab tests and imaging tests. While there are no specific tests to diagnose alcohol use disorder, certain patterns of lab test abnormalities may strongly suggest it. And you may need tests to identify health problems that may be linked to your alcohol use. Damage to your organs may be seen on tests.

- Complete a psychological evaluation. This evaluation includes questions about your symptoms, thoughts, feelings and behavior patterns. You may be asked to complete a questionnaire to help answer these questions.

- Use the DSM-5 criteria. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association, is often used by mental health professionals to diagnose mental health conditions.

DSM-5 alcohol use disorder

DSM-5 Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder 58:

- Criterion A. A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

- Alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol, or recover from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol.

- Recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued alcohol use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use.

- Recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Alcohol use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol.

- Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

- a. A need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve intoxication or desired effect.

- b. A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol.

- Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following:

- a. The characteristic withdrawal syndrome for alcohol.

- b. Alcohol (or a closely related substance, such as a benzodiazepine) is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Specify if:

- In early remission: After full criteria for alcohol use disorder were previously met, none of the criteria for alcohol use disorder have been met for at least 3 months but for less than 12 months (with the exception that Criterion A4, “Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol,” may be met).

- In sustained remission: After full criteria for alcohol use disorder were previously met, none of the criteria for alcohol use disorder have been met at any time during a period of 12 months or longer (with the exception that Criterion A4, “Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol,” may be met).

Specify if:

- In a controlled environment: This additional specifier is used if the individual is in an environment where access to alcohol is restricted.

Alcohol use disorder is defined by a cluster of behavioral and physical symptoms, which can include withdrawal, tolerance, and craving. Alcohol withdrawal is characterized by withdrawal symptoms that develop approximately 4-12 hours after the reduction of intake following prolonged, heavy alcohol ingestion. Because withdrawal from alcohol can be unpleasant and intense, individuals may continue to consume alcohol despite adverse consequences, often to avoid or to relieve withdrawal symptoms. Some withdrawal symptoms (e.g., sleep problems) can persist at lower intensities for months and can contribute to relapse. Once a pattern of repetitive and intense use develops, individuals with alcohol use disorder may devote substantial periods of time to obtaining and consuming alcoholic beverages.

Craving for alcohol is indicated by a strong desire to drink that makes it difficult to think of anything else and that often results in the onset of drinking. School and job performance may also suffer either from the aftereffects of drinking or from actual intoxication at school or on the job; child care or household responsibilities may be neglected; and alcohol-related absences may occur from school or work. The individual may use alcohol in physically hazardous circumstances (e.g., driving an automobile, swimming, operating machinery while intoxicated). Finally, individuals with an alcohol use disorder may continue to consume alcohol despite the knowledge that continued consumption poses significant physical (e.g., blackouts, liver disease), psychological (e.g., depression), social, or interpersonal problems (e.g., violent arguments with spouse while intoxicated, child abuse).

Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder

Alcohol use disorder is when your drinking causes serious problems in your life, yet you keep drinking. You may also need more and more alcohol to feel drunk. Stopping suddenly may cause withdrawal symptoms. This means that your drinking causes distress and harm. It includes alcoholism and alcohol abuse. Many people with an alcohol problem need to completely stop using alcohol. This is called abstinence. Having strong social and family support can help make it easier to quit drinking.

Some people are able to just cut back on their drinking. So even if you do not give up alcohol altogether, you may be able to drink less. This can improve your health and relationships with others. It can also help you perform better at work or school.

However, many people who drink too much find they can’t just cut back. Abstinence may be the only way to manage a drinking problem.

The good news is that no matter how severe the problem may seem, most people with an alcohol use disorder can benefit from some form of treatment.

Research shows that about one-third of people who are treated for alcohol problems have no further symptoms 1 year later. Many others substantially reduce their drinking and report fewer alcohol-related problems.

Ultimately, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and what may work for one person may not be a good fit for someone else. Simply understanding the different options can be an important first step.

Treatment for alcohol use disorder may include:

- Detox and withdrawal. Treatment may begin with a program of detoxification or detox — withdrawal that’s medically managed — which generally takes two to seven days. You may need to take sedating medications to prevent withdrawal symptoms. Detox is usually done at an inpatient treatment center or a hospital.

- Learning skills and establishing a treatment plan. This usually involves alcohol treatment specialists. It may include goal setting, behavior change techniques, use of self-help manuals, counseling and follow-up care at a treatment center.

- Psychological counseling. Counseling and therapy for groups and individuals help you better understand your problem with alcohol and support recovery from the psychological aspects of alcohol use. You may benefit from couples or family therapy — family support can be an important part of the recovery process.

- Oral medications. A drug called disulfiram (Antabuse) may help prevent you from drinking, although it won’t cure alcohol use disorder or remove the compulsion to drink. If you drink alcohol, the drug produces a physical reaction that may include flushing, nausea, vomiting and headaches. Naltrexone, a drug that blocks the good feelings alcohol causes, may prevent heavy drinking and reduce the urge to drink. Acamprosate may help you combat alcohol cravings once you stop drinking. Unlike disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate don’t make you feel sick after taking a drink.

- Injected medication. Vivitrol, a version of the drug naltrexone, is injected once a month by a health care professional. Although similar medication can be taken in pill form, the injectable version of the drug may be easier for people recovering from alcohol use disorder to use consistently.

- Continuing support. Aftercare programs and support groups help people recovering from alcohol use disorder to stop drinking, manage relapses and cope with necessary lifestyle changes. This may include medical or psychological care or attending a support group.

- Treatment for psychological problems. Alcohol use disorder commonly occurs along with other mental health disorders. If you have depression, anxiety or another mental health condition, you may need talk therapy (psychotherapy), medications or other treatment.

- Medical treatment for health conditions. Many alcohol-related health problems improve significantly once you stop drinking. But some health conditions may warrant continued treatment and follow-up.

- Spiritual practice. People who are involved with some type of regular spiritual practice may find it easier to maintain recovery from alcohol use disorder or other addictions. For many people, gaining greater insight into their spiritual side is a key element in recovery.

Some people may need intensive treatment for alcohol use disorder. They may go to a residential treatment center for rehabilitation (rehab). Residential treatment programs typically include licensed alcohol and drug counselors, social workers, nurses, doctors and others with expertise and experience in treating alcohol use disorder. Treatment there is highly structured. It usually includes several different kinds of behavioral therapies. Most residential treatment programs include individual and group therapy, support groups, educational lectures, family involvement and activity therapy. It may also include medicines for detox (medical treatment for alcohol withdrawal) and/or for treating the alcohol use disorder.

DECIDING TO QUIT

Like many people with an alcohol problem, you may not recognize that your drinking has gotten out of hand. An important first step is to be aware of how much you drink. It also helps to understand the health risks of alcohol.

If you decide to quit drinking, talk with your provider. Treatment involves helping you realize how much your alcohol use is harming your life and the lives those around you.

Depending on how much and how long you have been drinking, you may be at risk for alcohol withdrawal. Withdrawal can be very uncomfortable and even life threatening. If you have been drinking a lot, you should cut back or stop drinking only under the care of a doctor. Talk with your provider about how to stop using alcohol.

LONG-TERM SUPPORT

Alcohol recovery or support programs can help you stop drinking completely. These programs usually offer:

- Education about alcohol use and its effects

- Counseling and therapy to discuss how to control your thoughts and behaviors

- Physical health care

For the best chance of success, you should live with people who support your efforts to avoid alcohol. Some programs offer housing options for people with alcohol problems. Depending on your needs and the programs that are available:

- You may be treated in a special recovery center (inpatient)

- You may attend a program while you live at home (outpatient)

You may be prescribed medicines to help you quit. They are often used with long-term counseling or support groups. These medicines make it less likely that you will drink again or help limit the amount you drink.

Drinking may mask depression or other mood or anxiety disorders. If you have a mood disorder, it may become more noticeable when you stop drinking. Your provider will treat any mental disorders in addition to your alcohol treatment.

Support Groups for Alcohol use disorder

Because an alcohol use disorder can be a chronic relapsing disease, persistence is key. It is rare that someone would go to treatment once and then never drink again. More often, people must repeatedly try to quit or cut back, experience recurrences, learn from them, and then keep trying. For many, continued followup with a treatment provider is critical to overcoming problem drinking. Support groups help many people who are dealing with alcohol use and relapses.

Relapse is common among people who overcome alcohol problems. People with drinking problems are most likely to relapse during periods of stress or when exposed to people or places associated with past drinking.

Just as some people with diabetes or asthma may have flare-ups of their disease, a relapse to drinking can be seen as a temporary set-back to full recovery and not a complete failure. Seeking professional help can prevent relapse — behavioral therapies can help people develop skills to avoid and overcome triggers, such as stress, that might lead to drinking. Most people benefit from regular checkups with a treatment provider. Medications also can deter drinking during times when individuals may be at greater risk of relapse (e.g., divorce, death of a family member).

If you cannot stop drinking, GET HELP. You may have a disease called alcoholism. There are programs that can help you stop drinking. They are called alcohol treatment programs. Your doctor or nurse can find a program to help you. Even if you have been through a treatment program before, try it again. There are also programs just for women.

Consider joining Alcoholics Anonymous or another mutual support group (see links below). Recovering people who attend groups regularly do better than those who do not. Groups can vary widely, so shop around for one that’s comfortable. You’ll get more out of it if you become actively involved by having a sponsor and reaching out to other members for assistance.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (https://www.aa.org)

- Moderation Management (https://moderation.org)

- Secular Organizations for Sobriety (https://www.sossobriety.org)

- SMART Recovery (https://www.smartrecovery.org)

- Women for Sobriety (https://womenforsobriety.org)

- Al-Anon Family Groups (https://al-anon.org)

- Adult Children of Alcoholics (https://adultchildren.org)

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (https://recovered.org)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov)

- National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (https://fasdunited.org)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://findtreatment.gov)

Medications for alcohol use disorder

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three medications for treating alcohol dependence, and alcohol use disorder (see Table 1 below) 59. All of these medications are non-addictive, so you don’t have to worry about trading one addiction for another. Your health care provider can help you figure out if one of these medicines is right for you. They are not a cure, but they can help you manage alcohol use disorder. This is just like taking medicines to manage a chronic disease such as asthma or diabetes.

- Naltrexone can help people reduce heavy drinking.

- Acamprosate makes it easier to maintain abstinence.

- Disulfiram blocks the breakdown (metabolism) of alcohol by the body, causing unpleasant symptoms such as nausea and flushing of the skin. Those unpleasant effects can help some people avoid drinking while taking disulfiram.

It is important to remember that not all people will respond to medications, but for a subset of individuals, they can be an important tool in overcoming alcohol dependence.

Of the FDA approved medications, the two newer ones (naltrexone and acamprosate) can make it easier to quit drinking by offsetting changes in the brain caused by alcoholism. They don’t make you sick if you do drink, unlike the older approved medication (disulfiram) 60.

Used in the context of a comprehensive treatment plan, medications for alcohol use disorder can provide an opportunity for behavioral therapies (counseling) to be helpful by reducing craving or helping to maintain abstinence from alcohol. In that way, medications can give people with an alcohol problem some traction in the recovery process.

It’s important to consult a doctor who understands which people are good candidates for alcohol use disorder medications. Some studies suggest that people with a family history of alcohol use disorder may be likely to benefit from naltrexone, for example. But those who have a liver condition or use opioid medications (such as those prescribed for pain) should not take naltrexone. A doctor can assess these and other conditions and match an appropriate medication with the patient.

As with any other medication, patients should communicate with their doctor about how the medication is working, and the doctor may be able to adjust the dose if needed.

Medications for alcohol use disorder can be prescribed not only by specialists in addiction treatment, but also by primary care physicians.

Scientists are working to develop a larger menu of pharmaceutical treatments that could be tailored to individual needs. As more medications become available, people may be able to try multiple medications to find which they respond to best.

Certain medications already approved for other uses have shown promise for treating alcohol dependence and problem drinking:

- The anti-smoking drug varenicline (marketed under the name Chantix) significantly reduced alcohol consumption and craving among people with alcoholism.

- Gabapentin, a medication used to treat pain conditions and epilepsy, was shown to increase abstinence and reduce heavy drinking. Those taking the medication also reported fewer alcohol cravings and improved mood and sleep.

- The anti-epileptic medication topiramate was shown to help people curb problem drinking, particularly among those with a certain genetic makeup that appears to be linked to the treatment’s effectiveness.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone blocks opioid receptors that are involved in the rewarding effects of drinking and the craving for alcohol 61. Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist, reduces alcohol consumption in patients with alcohol use disorder and is more successful in those who are abstinent before starting the medication 62. The opioid receptor system mediates the pleasurable effects of alcohol. Alcohol ingestion stimulates endogenous opioid release and increases dopamine transmission. Naltrexone blocks these effects, reducing euphoria and cravings 63. Naltrexone comes either as a pill that is taken daily, or as an injection that can be given once per month. Because naltrexone is metabolized by the liver, liver toxicity is possible, although uncommon. Patients with alcohol use disorder may have liver dysfunction; therefore, caution is warranted. Naltrexone can precipitate severe opioid withdrawal in patients who are opioid-dependent, so these agents should not be used together, and opioids should not be used for at least seven days before starting naltrexone 62. Pain management is challenging for patients taking naltrexone; these patients should carry a medical alert card.

Naltrexone is well tolerated and is not habit-forming. Naltrexone can also reduce your craving for alcohol. This can help you cut back on your drinking.

A Cochrane review that included 50 randomized trials and 7,793 patients found that oral naltrexone decreased heavy drinking (number needed to treat (NNT) = 10) and slightly decreased daily drinking (NNT = 25). The number of heavy drinking days and the amount of alcohol consumed also decreased. Injectable naltrexone did not decrease heavy drinking, but the sample size was small 64. A subsequent systematic review of 53 randomized trials including 9,140 patients found that oral naltrexone increased abstinence rates (NNT = 20) and decreased heavy drinking (NNT = 12). There was no difference between naltrexone and acamprosate. Injectable naltrexone did not demonstrate benefit 65. A randomized trial of 627 veterans with alcohol use disorder who received injectable naltrexone or placebo found that 380 mg of naltrexone given intramuscularly decreased heavy drinking days over six months but did not increase abstinence rates 66. Another meta-analysis found no difference in heavy drinking between acamprosate and naltrexone; however, it favored acamprosate for abstinence and naltrexone for cravings 67. Studies of combination therapy with acamprosate and naltrexone have produced mixed results. The COMBINE study did not show that combined therapy was more effective than either agent alone 68. Another study showed that relapse rates were lower with combined therapy compared with placebo or acamprosate alone, but not compared with naltrexone alone 69. It is unclear if and when combination therapy should be used, although it may be reasonable to consider it if monotherapy fails. Opioid antagonists may also be helpful when used as needed during high-risk situations, such as social events or weekends 70.

Like any medicine, naltrexone can cause side effects. Nausea is the most common one. Other side effects include:

- Headache

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Dizziness

- Nervousness

- Insomnia

- Drowsiness

- Anxiety

If you get any of these side effects, tell your doctor. They may change your treatment or suggest ways you can deal with the side effects.

Call your doctor immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms:

- Blurry vision

- Confusion

- Hallucinations (hearing or seeing things that aren’t there)

- Severe vomiting or diarrhea

- Vomiting up blood

- Excessive fatigue

- Bleeding or bruising

- Loss of appetite

- Pain in the upper right part of your stomach that lasts more than a few days

- Light-colored bowel movements

- Dark urine

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes

Talk to your doctor if you have a history of depression. Naltrexone may cause liver damage when taken in large doses. Tell your doctor if you have had hepatitis or liver disease.

Acamprosate

Acamprosate (Campral®) acts on the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate neurotransmitter systems and is thought to reduce symptoms of protracted withdrawal, such as insomnia, anxiety, restlessness, and dysphoria 61. Acamprosate has been shown to help dependent drinkers maintain abstinence for several weeks to months, and it may be more effective in patients with severe dependence. Acamprosate is a pill that is taken three times per day.

Acamprosate appears to be most effective at maintaining abstinence in patients who are not currently drinking alcohol 67. Acamprosate seems to interact with glutamate at the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, although its exact mechanism is unclear 71. Acamprosate is safe in patients with impaired liver function but should be avoided in patients with severe kidney dysfunction. A systematic review of 27 studies including 7,519 patients using acamprosate showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 12 to prevent a return to any drinking 65. A Cochrane review of 24 trials including 6,915 patients concluded that acamprosate reduced drinking compared with placebo (NNT = 9) 72. One randomized trial found no difference between acamprosate and placebo, although outcomes improved significantly in both groups. This may be because enrolled patients were highly motivated to decrease alcohol use, increasing the likelihood of success with any treatment 73.

Disulfiram

Disulfiram (Antabuse®) interferes with degradation of alcohol, resulting in the accumulation of acetaldehyde, which, in turn, produces a very unpleasant reaction that includes flushing, nausea, and plapitations whenever you drink alcohol 61. Knowing that drinking will cause these unpleasant effects may help you stay away from alcohol. The utility and effectiveness of disulfiram are considered limited because compliance is generally poor. However, among patients who are highly motivated, disulfiram can be effective, and some patients use it episodically for high-risk situations, such as social occasions where alcohol is present. It can also be administered in a monitored fashion, such as in a clinic or by a spouse, improving its efficacy.

There are limited trials to support the effectiveness of disulfiram. It does not reduce the craving for alcohol, but it causes unpleasant symptoms when alcohol is ingested because it inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase and alcohol metabolism. Compliance is a major limitation, and disulfiram is more effective when taken under supervision. One trial randomized 243 patients to naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram with supervision over 12 weeks and determined that patients taking disulfiram had fewer heavy drinking days, lower weekly consumption, and a longer period of abstinence compared with the other drugs 74. However, a 2014 meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials found that in open-label studies, disulfiram was more effective than naltrexone, acamprosate, and no disulfiram, but blinded studies did not demonstrate benefit for disulfiram 75. In a systematic review of two studies including 492 patients, disulfiram did not reduce drinking rates 65. A review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality on pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol-use disorders in outpatient settings found insufficient evidence to support disulfiram’s effectiveness 76.

Topiramate

Topiramate is thought to work by increasing inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmission and reducing stimulatory (glutamate) neurotransmission, although its precise mechanism of action is not known 61. Although topiramate has not yet received FDA approval for treating alcohol addiction, it is sometimes used off-label for this purpose. Topiramate has been shown in studies to significantly improve multiple drinking outcomes, compared with a placebo.

Isn’t taking medications just trading one addiction for another?

This is not an uncommon concern, but the short answer is “no.” All medications approved for treating alcohol dependence are non-addictive 59. These medicines are designed to help manage a chronic disease, just as someone might take drugs to keep their cholesterol or diabetes in check.

Behavioral therapies

Another name for behavioral therapies for alcohol use disorder is alcohol counseling. It involves working with a health care professional to identify and help change the behaviors that lead to your heavy drinking.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) helps you identify the feelings and situations that can lead to heavy drinking. It teaches you coping skills, including how to manage stress and how to change the thoughts that cause you to want to drink. You may get CBT one-on-one with a therapist or in small groups.

- Motivational enhancement therapy helps you build and strengthen the motivation to change your drinking behavior. It includes about four sessions over a short period of time. The therapy starts with identifying the pros and cons of seeking treatment. Then you and your therapist work on forming a plan for making changes in your drinking. The next sessions focus on building up your confidence and developing the skills you need to be able to stick to the plan.

- Marital and family counseling includes spouses and other family members. It can help to repair and improve your family relationships. Studies show that strong family support through family therapy may help you to stay away from drinking.

- Brief interventions are short, one-on-one or small-group counseling sessions. It includes one to four sessions. The counselor gives you information about your drinking pattern and potential risks. The counselor works with you to set goals and provide ideas that may help you make a change.

Lifestyle choices

As part of your recovery, you’ll need to focus on changing your habits and making different lifestyle choices. These strategies may help.

- Consider your social situation. Make it clear to your friends and family that you’re not drinking alcohol. Develop a support system of friends and family who can support your recovery. You may need to distance yourself from friends and social situations that impair your recovery.

- Develop healthy habits. For example, good sleep, regular physical activity, managing stress more effectively and eating well all can make it easier for you to recover from alcohol use disorder.

- Do things that don’t involve alcohol. You may find that many of your activities involve drinking. Replace them with hobbies or activities that are not centered around alcohol.

Alternative medicine

Avoid replacing conventional medical treatment or psychotherapy with alternative medicine. But if used in addition to your treatment plan when recovering from alcohol use disorder, these techniques may be helpful:

- Yoga. Yoga’s series of postures and controlled breathing exercises may help you relax and manage stress.