Somatostatinoma

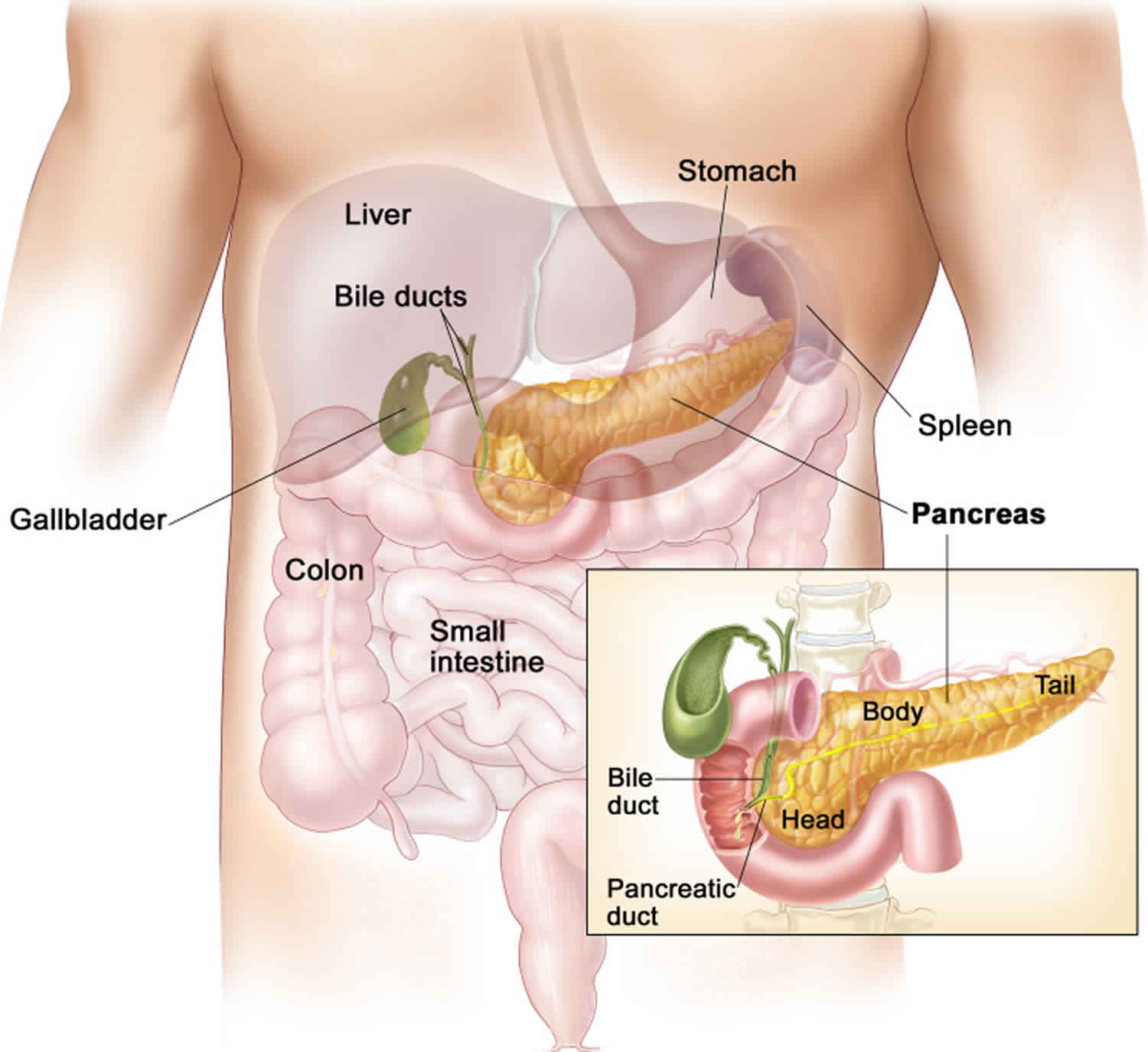

Somatostatinoma is a rare neuroendocrine tumor that make the hormone somatostatin. Somatostatinomas are cancers. Somatostatinomas usually grow slowly and the symptoms can be vague. So people are often diagnosed when the cancer has already spread to other parts of the body (secondary tumours or metastases). The most common places where somatostatinomas spread to is the liver and lymph nodes. Somatostatin hormone controls the production of other hormones by the pancreas. Somatostatin also controls how the gut works. Somatostatinomas are a type of functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Somatostatinomas are also a type of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Most somatostatinomas start in the pancreas and the small bowel (duodenum) 1.

Although somatostatinoma secretes somatostatin, clinical presentations related to high somatostatin levels are found in less than 10% of cases depending on the location of the tumor, as well as intermittent somatostatin secretion from the tumor 2. If somatostatinoma syndrome is fully present, then it consists of diabetes mellitus, diarrhea/steatorrhea, gallbladder disease (particularly cholelithiasis), hypochlorhydria, and weight loss 3.

More than 50 out of every 100 somatostatinomas (50%) start in the pancreas. Pancreatic tumors usually start in the widest part of the pancreas (head).

More than 40 out of every 100 somatostatinomas (40%) start in the small bowel (duodenum).

More rarely somatostatinomas can start in:

- the middle part of the small bowel (jejunum)

- a tube called cystic duct that connects the gallbladder to the common bile duct

Somatostatinomas are extremely rare, with an incidence rate of 1 in 40 million people 4. Only 1 out of every 100 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (1%) diagnosed every year are somatostatinomas. Somatostatinoma presents mostly as asymptomatic tumor diagnosed incidentally on imaging or surgery when evaluating or treating possible causes of abdominal pain. Somatostatinoma also can present with vague symptoms, or as a clinical triad of glucose intolerance, steatorrhea, and achlorhydria 4. The majority of somatostatinomas are present in the pancreatic head, followed by the duodenum, the pancreatic tail, and rarely the ampulla of Vater. The prognosis is poor as more than 77% of cases present as advanced disease with local invasion or distant metastasis. Surgical resection is the main treatment for early stage disease. Other treatment options include somatostatin analogue, molecular targeted therapy, and cytotoxic chemotherapy. The scarcity of somatostatinoma cases led to the lack of fully formulated treatment options.

Somatostatinoma causes

Scientists don’t know exactly what causes most pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), but they have found several risk factors that can make a person more likely to get this disease. Some of these risk factors affect the DNA of cells in the neuroendocrine system in the pancreas, which can result in abnormal cell growth and may cause cancers to form.

DNA is the chemical in your cells that carries our genes, which control how your cells function. You look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. But DNA affects more than just how you look.

Cancers can be caused by DNA changes (mutations) that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes.

Inherited gene mutations

Although 90% of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are sporadic (random), some people inherit gene changes from their parents that raise their risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Sometimes these gene changes are part of syndromes that include increased risks of other health problems as well.

Syndromes related to changes in three tumor suppressor genes are responsible for many inherited cases of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors:

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1) syndrome: Most inherited cases of Pneuroendocrine tumors are due to changes in the MEN1 gene. This syndrome can cause cancer in the pancreas, parathyroid glands, and pituitary glands. These tumors usually happen at younger ages and tend to be non-functioning. Screening people with the MEN1 gene or their family members can sometimes help find pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor before symptoms appear.

- Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome: Changes in the VHL gene cause a small number of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, usually developing at earlier ages (sometimes as early as the 20s). These tumors tend to be non-functioning and slow growing.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) syndrome: A small number of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (usually somatostatinomas) are caused by changes in the NF1 gene. Other cancers are also associated with this syndrome, including brain tumors or benign tumors that form in nerves under the skin (neurofibromas),

The treatment for a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor that’s caused by a genetic syndrome might be slightly different compared to treatment for a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor in someone without a gene mutation.

Acquired gene mutations

Most gene mutations related to neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas are caused by random changes. These random mutations are called acquired if they occur after a person is born, rather than having been inherited. These acquired gene mutations sometimes result from exposure to cancer-causing chemicals (like those found in tobacco smoke). But often what causes these changes is not known.

Risk factors for somatostatinoma

A risk factor is anything that increases your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

But having a risk factor, or even many risk factors, does not mean that you will get the disease. And some people who get the disease may have few or no known risk factors.

Several factors can affect a person’s chance of getting a neuroendocrine tumor (neuroendocrine tumor) of the pancreas.

Risk factors that can be changed

Smoking

Smoking is a risk factor for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Most research shows that heavy smoking increases risk, but some studies show that any history of smoking could put you at risk.

Alcohol

Some studies have shown a link between heavy alcohol use and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. This link appears to be mostlyrelated to functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors rather than nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Heavy alcohol use can also lead to conditions such as chronic pancreatitis, which may increase pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor risk.

Risk factors that can’t be changed

Family history

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors seem to run in some families. In some of these families, the high risk is due to an inherited syndrome (explained below). In other families, the gene causing the increased risk is not known. If family history is a risk factor, it usually involves a first degree relative (parent, sibling, child), a family history of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, or a family history of any cancer.

Inherited genetic syndromes

Inherited gene changes (mutations) can be passed from parent to child. Sometimes these changes result in syndromes that include increased risks of other cancers (or other health problems).

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and cancers can also be caused by genetic syndromes, such as:

- Neurofibromatosis, type 1, which is caused by mutations in the NF1 gene. This syndrome leads to an increased risk of many tumors, including somatostatinomas.

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1 (MEN1), caused by mutations in the MEN1 gene. This syndrome leads to an increased risk of tumors of the parathyroid gland, the pituitary gland, and the islet cells of the pancreas.

- Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome, which is caused by mutations in the VHL gene. This syndrome leads to an increased risk of many tumors, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Changes in the genes that cause some of these syndromes can be found by genetic testing.

Diabetes

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are more common in people with diabetes. The reason for this is not known. Most of the risk is found in people with type 2 diabetes. This type of diabetes most often starts in adulthood and is often related to being overweight or obese. It’s not clear if people with type 1 (juvenile) diabetes have a higher risk.

Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis, a long-term inflammation of the pancreas, is linked with an increased risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. If chronic pancreatitis is because of heavy alcohol use, then stopping alcohol may help decrease the risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Factors with unclear effect on risk

Being overweight or obese

Being overweight or obese could be a risk factor for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Studies so far are inconclusive.

Coffee

Some older studies have suggested that drinking coffee might increase the risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, but more recent studies have not confirmed this.

Somatostatinoma symptoms

Most patients presenting with somatostatinoma are over 50 years of age 1. Males represent about 58% and 40% of duodenal and pancreatic somatostatinomas, respectively, which contrasts with the equal sex incidence for other islet cell tumors 5. The most common symptom for all somatostatinomas is abdominal pain, occurring in over 50% of somatostatinomas 6. Duodenal tumors can also present with jaundice (23%) and gastrointestinal bleeding (22%), while pancreatic tumors are found incidentally in 35% of cases.

Classic somatostatinoma syndrome is described as a triad of diabetes mellitus, diarrhea and gallstones, but also includes weight loss and hypochlorhydria. Review of the literature on the incidence of the syndrome in less than 1% of patients and it usually occurs in pancreatic somatostatinomas as opposed to intestinal tumors.

Symptoms caused by somatostatin

Somatostatin is a hormone that controls the production of other hormones by the pancreas. It also controls how the gut works. An increase in the amount of somatostatin can cause:

Diabetes

Diabetes is a condition where the blood sugar levels become too high. Between 60 and 90 out of every 100 people with somatostatinomas (60 to 90%) have diabetes. Seventy-five percent of patients with pancreatic somatostatinomas have diabetes. In contrast, diabetes occurs only in 11% of patients with intestinal tumors. The diabetes is usually mild and can be controlled with diet and/or oral hypoglycemic agents or with small doses of insulin.

It is not clear, however, whether the differential inhibition of insulin and diabetogenic hormones can explain the usual mild degree of diabetes and the rarity of ketoacidosis in patients with somatostatinoma. Replacement of functional islet cell tissue by pancreatic tumor may be another reason for the development of diabetes in most patients with pancreatic somatostatinoma, contrasting with the low incidence in patients with intestinal ones.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea means having more than 3 watery poos (stools) in a 24 hour period. You might also have diarrhoea at night and problems controlling your bowels (incontinence).

Between 30 and 90 out of every 100 people with somatostatinomas (30 to 90%) have diarrhea.

Gallstones

Gallstones are small stones that form in the gallbladder. Between 60 and 90 out of every 100 people with somatostatinomas (60 to 90%) have gallstones. This is also called cholelithiasis.

Fifty-nine percent of patients with pancreatic tumors and 27% of patients with intestinal tumors have gallbladder disease. The high incidence of gallbladder disease in patients with somatostatinoma and the absence of such an association in any other islet cell tumor, suggests a causal relationship between gallbladder disease and somatostatinoma. Infusion of somatostatin into normal human subjects has been shown to inhibit gallbladder emptying 7, suggesting that somatostatin-mediated inhibition of gallbladder emptying may cause the observed high rate of gallbladder disease in patients with somatostatinoma. This thesis is supported by the observation of massively dilated gallbladders without stones or other pathology 8 in patients with somatostatin-secreting tumors.

Weight loss

You might lose weight even if you haven’t changed your diet. Weight loss may be significant over several months and may occur in about one-third of patients with pancreatic tumors and one-fifth of patients with intestinal tumors. The weight loss may relate to malabsorption and diarrhea, but in small intestinal tumors, anorexia, abdominal pain, and yet unexplained reasons may be relevant.

Fatty poop (stools)

You may pass frequent, large bowel motions that:

- are pale colored

- are smelly

- float and are difficult to flush away

This is called steatorrhea.

Symptoms caused by somatostatinoma tumor itself

Symptoms might include:

Abdominal pain

- More than 40 out of every 100 people with somatostatinomas (more than 40%) have tummy pain.

Jaundice

Jaundice is yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes. The urine can get darker than normal and bowel motions may be lighter in color. This is more common in people with somatostatinomas that start in the small bowel.

This happens because the cancer blocks a tube called bile duct. The bile duct carries bile into the small bowel.

Jaundice is a medical emergency. Speak to your doctor or go to your local emergency room if you think you have jaundice.

Blockage in the bowel

Sometimes the cancer can block the bowel (bowel obstruction). Symptoms of bowel obstruction include:

- griping pain in the tummy

- feeling bloated

- constipation and being unable to pass wind

- feeling sick

A bowel obstruction is an emergency. You should see your doctor or go to your local emergency room if you think you have a bowel obstruction.

Bleeding

Somatostatinomas can cause bleeding from the bowel or stomach. You may not be able to see any blood if it is a small amount. Or you may see blood in the vomit or poop. Over time, bleeding reduces the number of red blood cells in your blood (anemia).

Speak to your doctor if you see blood in your poop, or if your stools are back or sticky.

Somatostatinoma outside the gastrointestinal tract

Somatostatin has been found in many tissues outside the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Prominent among those are the hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic regions of the brain, the peripheral nervous system (including the sympathetic adrenergic ganglia), and the C cells of the thyroid gland. Therefore, high concentrations of somatostatin have been found in tumors originating from these tissues. Sano and colleagues 9 and Saito and colleagues 10 reported seven patients with medullary carcinoma of the thyroid who had high basal plasma somatostatin concentrations and high tumor somatostatin concentrations. Roos and colleagues 11 reported elevated plasma somatostatin concentrations in three of seven patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma and high tissue somatostatin concentrations in three of five thyroid tumors. Some, but not all, of these patients exhibited the clinical somatostatinoma syndrome.

Elevated plasma somatostatin concentrations also have been reported in patients with small cell lung cancer 11. One case of metastatic bronchial oat cell carcinoma caused Cushing’s syndrome, diabetes, diarrhea, steatorrhea, anemia, and weight loss and had a plasma somatostatin concentration 20 times greater than normal 12. A patient with a bronchogenic carcinoma presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis and high levels of somatostatin (> 5,000 pg/mL) has been reported 13.

Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are other examples of neuroendocrine tumors that produce and secrete somatostatin in addition to other hormonally active substances 14.

Most recently, a new syndrome including multiple paragangliomas, duodenal somatostatinomas (exclusively found in the ampulla of Vater) associated with high erythropoietin (polycythemia), has been described 15. Interestingly, the associate gene defect is one of a tumor somatic gain-of-function HIF2A mutation resulting in the stabilization of HIF-2α, which is known to upregulate the erythropoietin gene accounting for polycythemia in these patients.

Somatic gain-of-function of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF1,)2A mutations have been described in somatostatinomas associated with polycythemia and paragangliomas. These mutations affect prolyl hydroxylation and pVHL (Von Hippel–Lindau protein) protein binding and reduce HIF2α degradation but not transcriptional activity. pVHL is part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets HIF α for proteasomal degradation 13. Interaction of pVHL with HIF α is determined by hydroxylation status that oxygen (O2) dependent and catalyzed by family of prolyl hydroxylases (PHD1-3). HIF α stabilization can occur as a result of mutations in either PHD or VHL 16. Germline mutations in PHD2 have been associated with congenital polycythemia and extra-adrenal PGLs. VHL mutations prevent pVHL from binding hydroxylated HIF α and targeting it for proteasomal degradation as a result of either PHD or VHL mutation, Thus, HIF α accumulates in cytoplasm, translocates to nucleus, forms heterodimers between HIF α and β and activates transcription of target genes involved in tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, rbc proliferation and metabolic abnormalities.

Somatostatinoma diagnosis

Somatostatinomas are usually found during exploratory laparotomy, upper gastrointestinal (GI) radiographic studies, CT/MRI, ultrasound, or gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy studies that are performed due to various symptoms and signs, including unexplained abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, melena, hematemesis, persistent diarrhea, weight losss, fatigue, and anemia. In some patients, severe fasting hypoglycemia or severe diabetes may be also present 17. Once a tumor is found, somatostatinoma is identified by the demonstration of elevated tissue concentrations of somatostatin by immunohistochemistry and/or elevated plasma somatostatin concentrations.

You usually start by seeing your family doctor. They will ask you about your general health, symptoms and may also examine you.

Your family doctor might check your blood pressure, heart rate and temperature. They may arrange for you to have blood tests. Your family doctor will then decide if you need to see a specialist.

The specialist might ask you to have more tests. If tests show that you have a neuroendocrine tumor, your specialist will refer you to a team of doctors who have expertise in treating neuroendocrine tumors.

You’ll have tests to check whether you have a neuroendocrine tumor, the type of neuroendocrine tumor you have, the size of the tumor and whether it has spread. This helps your doctor plan your treatment.

A blood test to check the amount of somatostatin

This test measures the amount of the hormone somatostatin in your body. You must not eat anything between 8 and 12 hours before having this test.

Blood tests

Blood tests can check your general health. They can also check the levels of certain substances in the blood which are sometimes raised with neuroendocrine tumors.

You may also have a blood test to check for a rare inherited condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1). This test is usually only requested by specialist doctors (genetic doctors).

CT scan

This can show up a neuroendocrine tumor and see whether it has spread anywhere else in your body.

MRI scan

An MRI scan takes detailed pictures of your body. You might have an MRI scan to check if your neuroendocrine tumor has spread to other parts of the body such as the liver.

Endoscopy

This test looks at the inside of your food pipe, stomach and bowel. Your doctor uses a long flexible tube which has a tiny camera and a light on the end of it. Doctors can take samples of any abnormal areas (biopsies).

Endoscopic ultrasound scan (EUS)

This test combines an ultrasound and endoscopy to look at the inside at your food pipe, stomach, pancreas and bile ducts.

Your doctor uses a long flexible tube (endoscope) with a tiny camera and light on the end. It also has an ultrasound probe. The ultrasound helps the doctor find areas that might be cancer. They then can take samples (biopsies) of any abnormal areas.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can help to look for abnormal areas in the liver, bile duct, pancreas or gallbladder.

You might have an ERCP if you have yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice). Your doctor might put a stent into the bile duct to help with the symptoms of jaundice at the same time.

Radioactive scan

These are octreotide scans (or octreoscans) or gallium PET scans. You have an injection of a low dose radioactive substance, which is taken up by some neuroendocrine tumor cells. The cells then show up on the scan.

Surgical biopsy

Your surgeon takes samples of tissue during an operation called laparotomy. You might have this if the tumor is hard to reach.

Somatostatinoma treatment

The treatment you have for a somatostatinoma depends on a number of things such as where the tumor is, its size and whether it has spread (the stage). Surgery is the main treatment for somatostatinoma and gives the best chances of cure. But surgery isn’t always possible. Some somatostatinomas may have already started to spread when they are diagnosed. You may have treatment to control your symptoms if you can’t have surgery. Your doctor will discuss your treatment, its benefits and the possible side effects with you.

Deciding which treatment you need

A team of doctors and other professionals discuss the best treatment and care for you. They are called a multidisciplinary team.

The treatment you have depends on:

- where the somatostatinoma is and its size

- whether you have 1 or more tumors

- whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body

- your general health

- whether you have an inherited syndrome called multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1)

Although somatostatinomas are associated with a high rate of metastatic disease, survival rate is considerably high, especially in those with metastatic duodenal somatostatinoma 1. Thus, it is important to be aggressive in the management of these tumors and attempt to remove all tumor tissue if non-metastatic somatostatinoma is found initially. Surgical removal of somatostatinoma provides the only chance of cure. Most patients present with liver metastases, although not curative, event in these patients, surgical debulking of liver metastases as well as involved lymph nodes has been shown to provide symptomatic relief and prolong survival rate, given the slow growing nature of these tumors 18. Liver resection appears to be most appropriate for solitary lesions and oligometastases. Orthotopic liver transplantation has been performed in a small number of institutions with liver-only metastatic islet cell tumors 19. More extensive liver metastases can be treated by ablative methods including radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation, either alone or in combination with surgical resection 20. Hepatic artery embolization or chemoembolization with doxorubicin, cisplatin and mitomycin C of hepatic metastases can result in tumor regression and symptom palliation. Selective intra-arterial irradiation with yttrium labeled microspheres also has been reported with some success 21.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for somatostatinomas. Some of these are major operations and there are risks. But if the aim is to try to cure your somatostatinoma, you might feel it is worth some risks. Talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of your surgery.

You usually have an open surgery. Your surgeon makes a large cut in your tummy (abdomen) to remove the tumour. You also have an ultrasound scan during your operation to check for other tumours. Your surgeon might also remove the nearby lymph nodes.

You might have surgery to remove:

- just the tumor (enucleation)

- the whole of the pancreas (total pancreatectomy)

- the widest part of the pancreas, the duodenum, gallbladder and part of the bile duct (pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy or PPPD for short)

- the widest part of the pancreas, duodenum, gallbladder, part of the bile duct and part of the stomach (Whipple’s operation)

- the narrowest part of the pancreas and the body of the pancreas (distal pancreatectomy)

If the somatostatinoma has spread to the liver, you might be able to have the liver tumour removed at the same time you have the main surgery. Your surgeon may remove just the tumour, or part of the liver too.

Treatments to help with symptoms

You have treatments to help with symptoms if you can’t have surgery to remove the whole tumour for any reason.

These treatments control symptoms and help you feel better, rather than cure the somatostatinoma.

Surgery to remove part of the tumor

Removing part of the tumour can reduce your symptoms. Your doctor will only suggest surgery if they think it’s possible to remove most of the tumor (at least 90%).

Trans arterial embolization

You might have this treatment if the neuroendocrine tumor has spread to the liver.

Trans arterial embolization (TAE) means having a substance such as a gel or tiny beads to block the blood supply to the liver neuroendocrine tumor. It is also called hepatic artery embolisation.

You may also have a chemotherapy drug to the liver at the same time. This is called trans arterial chemoembolization (TACE). But doctors don’t know for sure whether adding chemotherapy is better than having embolisation alone for neuroendocrine tumors that have spread to the liver.

Embolization and chemoembolization work in two ways:

- it reduces the blood supply to the tumour and so starves it of oxygen and the nutrients it needs to grow

- it gives high doses of chemotherapy to the tumour without affecting the rest of the body

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses heat made by radio waves to kill tumour cells. You might have this if the neuroendocrine tumor has spread to the liver.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses anti cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy tumour cells. You may have chemotherapy if the neuroendocrine tumor has spread to the liver or to other parts of your body.

The most common chemotherapy drugs used are:

- streptozotocin or temozolomide

- fluorouracil or capecitabine

- doxorubicin

Somatostatin analogues

Somatostatin is a protein made naturally in the body. It does several things including slowing down the production of hormones. Somatostatin analogues are man made versions of somatostatin.

You may have somatostatin analogues to try to slow down the tumour and help with symptoms. The most common drugs used are:

- octreotide (Sandostatin)

- lanreotide (Somatuline)

Interferon

Interferon is also called interferon alfa. You may have it if the somatostatinoma has spread to other parts of the body. And other treatments have stopped working.

You may have interferon alone or together with somatostatin analogues.

Radiotherapy

You may have a type of internal radiotherapy called peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT). Internal radiotherapy means having radiotherapy from inside the body (as a drip into your bloodstream).

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) uses a radioactive substance called lutetium-177 or yttrium-90 attached to a somatostatin analogue.

You may have peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) if:

- your neuroendocrine tumor has spread to other parts of the body

- you can’t have surgery

- your neuroendocrine tumor has receptors on the outside of them called somatostatin receptors (you have special scans called octreotide or gallium PET scans to check for this)

Targeted drugs

Cancer cells have changes in their genes (DNA) that make them different from normal cells. These changes mean that they behave differently. Targeted drugs work by ‘targeting’ the differences that a cancer cell has and destroying them.

You may have 2 types of targeted drugs called everolimus and sunitinib.

Drugs to control blood sugar levels

You have treatment to control the blood sugar levels if they become too high. This is usually tablets, but you may also have insulin injections.

Clinical trials

Doctors are always trying to improve treatments and reduce the side effects. As part of your treatment, your doctor might ask you to take part in a clinical trial. This might be to test a new treatment or to look at different combinations of existing treatments.

Somatostatinoma survival rate

Survival for somatostatinomas depends on many factors. So no one can tell you exactly how long you will live.

Doctors usually work out the outlook for a certain disease by looking at large groups of people. Because somatostatinomas are rare cancers, the survival of this disease is harder to estimate than for other, more common cancers.

These are general statistics based on small groups of people. Remember, they can’t tell you what will happen in your individual case. Your doctor can give you more information about your own outlook (prognosis).

Survival depends on many factors. It depends on the stage and grade of the tumour when it was diagnosed. The stage describes the size of the tumour and whether it has spread. The grade means how abnormal the cells look under a microscope.

Another factor is how well you are overall.

Most people with a somatostatinoma that hasn’t spread to other parts of the body have surgery to try to cure their cancer.

Almost 80 out of every 100 people (almost 80%) survive somatostatinomas for 5 years or more after having surgery to try to cure their cancer.

- Vinik A, Pacak K, Feliberti E, et al. Somatostatinoma. [Updated 2017 Jun 14]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279034[↩][↩][↩]

- Mozell E, Stenzel P, Woltering EA, Rosch J, O’Dorisio TM. Functional endocrine tumors of the pancreas: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Probl Surg 1990; 27(6):301-386.[↩]

- Patel YC, Ganda OP, Benoit R. Pancreatic somatostatinoma: abundance of somatostatin-28(1-12)-like immunoreactivity in tumor and plasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1983; 57(5):1048-1053.[↩]

- Zakaria A, Hammad N, Vakhariya C, Raphael M. Somatostatinoma Presented as Double-Duct Sign. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2019;2019:9506405. Published 2019 May 9. doi:10.1155/2019/9506405 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6532322[↩][↩]

- CRAIN EL, Jr., THORN GW. Functioning pancreatic islet cell adenomas; a review of the literature and presentation of two new differential tests. Medicine (Baltimore) 1949; 28(4):427-447.[↩]

- Garbrecht N, Anlauf M, Schmitt A et al. Somatostatin-producing neuroendocrine tumors of the duodenum and pancreas: incidence, types, biological behavior, association with inherited syndromes, and functional activity. Endocr Relat Cancer 2008; 15(1):229-241.[↩]

- Fisher RS, Rock E, Levin G, Malmud L. Effects of somatostatin on gallbladder emptying. Gastroenterology 1987; 92(4):885-890.[↩]

- Axelrod L, Bush MA, Hirsch HJ, Loo SW. Malignant somatostatinoma: clinical features and metabolic studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1981; 52(5):886-896.[↩]

- Saito H, Saito S, Sano T, Kagawa N, Hizawa K, Tatara K. Immunoreactive somatostatin in catecholamine-producing extra-adrenal paraganglioma. Cancer 1982; 50(3):560-565.[↩]

- Saito S, Saito H, Matsumura M, Ishimaru K, Sano T. Molecular heterogeneity and biological activity of immunoreactive somatostatin in medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1981; 53(6):1117-1122.[↩]

- Roos BA, Lindall AW, Ells J, Elde R, Lambert PW, Birnbaum RS. Increased plasma and tumor somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in medullary thyroid carcinoma and small cell lung cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1981; 52(2):187-194.[↩][↩]

- Ghose RR, Gupta SK. Oat cell carcinoma of bronchus presenting with somatostatinoma syndrome. Thorax 1981; 36(7):550-551.[↩]

- Jackson JA, Raju BU, Fachnie JD et al. Malignant somatostatinoma presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1987; 26:609-621.[↩][↩]

- Vinik AI, Shapiro B, Thompson NW. Plasma gut hormone levels in 37 patients with pheochromocytomas. World J Surg 1986; 10(4):593-604.[↩]

- Yang C, Hong CS, Prchal JT, Balint MT, Pacak K, Zhuang Z. Somatic mosaicism of EPAS1 mutations in the syndrome of paraganglioma and somatostatinoma associated with polycythemia. Hum Genome Var 2015; 2:15053.[↩]

- Kloppel G, Anlauf M. Epidemiology, tumour biology and histopathological classification of neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005; 19(4):507-517.[↩]

- Tanaka S, Yamasaki S, Matsushita H et al. Duodenal somatostatinoma: a case report and review of 31 cases with special reference to the relationship between tumor size and metastasis. Pathol Int 2000; 50(2):146-152.[↩]

- Fendrich V, Langer P, Celik I et al. An aggressive surgical approach leads to long-term survival in patients with pancreatic endocrine tumors. Ann Surg 2006; 244(6):845-851.[↩]

- Le Treut YP, Gregoire E, Belghiti J et al. Predictors of long-term survival after liver transplantation for metastatic endocrine tumors: an 85-case French multicentric report. Am J Transplant 2008; 8(6):1205-1213.[↩]

- Brentjens R, Saltz L. Islet cell tumors of the pancreas: the medical oncologist’s perspective. Surg Clin North Am 2001; 81(3):527-542.[↩]

- King J, Quinn R, Glenn DM et al. Radioembolization with selective internal radiation microspheres for neuroendocrine liver metastases. Cancer 2008; 113(5):921-929.[↩]