Synovial osteochondromatosis

Synovial osteochondromatosis also called synovial chondromatosis, primary synovial chondromatosis or synovial chondrometaplasia, is a rare benign (noncancerous) condition that creates a benign change or proliferation in the synovium (the thin layer of tissue that lines the joints), which changes to form bone-forming cartilage. Synovial osteochondromatosis can arise in any joint in the body, but most commonly occurs in the knee, followed by the hip, elbow, and shoulder (the temporal mandibular joint, and the ankle may also be affected). In most cases, only one joint (monoarticular) in the body is affected although rare cases of multiple joint involvements occur. A rare occurrence is an extra-articular presentation of synovial-chondral lesions. This occurs in synovial lined bursal tissue or tenosynovium in which the typical chondral loose bodies form. These are referred to as tenosynovial chondromatosis or bursal chondromatosis. Synovial osteochondromatosis patients usually present with pain, swelling, and limitation of motion, which often progresses slowly for several years. Joint effusions are common as there is a restricted range of motion. Synovial osteochondromatosis most often occurs in patients between the ages of 30 and 50, it is rarely present before the age of 20, and it is very rare in children. Men are reported to be affected with synovial osteochondromatosis up to four times more commonly than women 1.

It is important to seek treatment for synovial osteochondromatosis as early as possible to help relieve painful symptoms and prevent the progression of osteoarthritis in the joint.

In synovial osteochondromatosis, the synovium grows abnormally and produces nodules made of cartilage. These nodules can sometimes break off from the synovium and become loose inside the joint. The size of the loose cartilage bodies inside the joint can vary—from a few millimeters (the size of a small pill) to a few centimeters (the size of a marble).

The synovial fluid nourishes the loose bodies and they may grow, calcify (harden), or ossify (turn into bone). When this occurs, they can roll around freely inside the joint space.

As they roll around, the loose bodies can damage the smooth articular cartilage that covers the joint, causing osteoarthritis. In osteoarthritis, damaged cartilage becomes worn and frayed. Moving the bones along this exposed joint surface is painful.

In severe cases of synovial chondromatosis, the loose bodies may grow large enough to occupy the entire joint space or penetrate into adjacent tissues.

These joints usually present as having a large effusion and sometimes appearing deformed due to swelling or synovial hypertrophy 1. They are painful at rest and are more painful with motion. The range of motion is usually decreased. X-ray evaluation reveals multiple loose radio-opaque chondroid bodies of varied sizes in a joint. MRI arthrogram enables better evaluation of the process and the extent of involvement within the joint and surrounding tissue.

Synovial osteochondromatosis is classified under two main types:

- Primary synovial osteochondromatosis: predominantly monoarticular disorder of unknown cause.

- Secondary synovial osteochondromatosis: resulting in intra-articular loose bodies from causes such as trauma, osteoarthrosis and neuropathic arthropathy

The primary and secondary synovial osteochondromatosis have different presentations, and as such are treated differently. In rare cases, an extra-articular form of synovial osteochondromatosis can be identified. In these cases, the lesions are found to be in bursal tissue and/or in tenosynovial tissue in proximity to an involved joint 2.

Although synovial osteochondromatosis is not cancerous, it can severely damage the affected joint and, eventually, lead to osteoarthritis. Early treatment is important to help relieve painful symptoms and prevent further damage to the joint.

Malignant degeneration into chondrosarcoma has been reported but is rare 3. Additionally, the cellular atypia demonstrated as synovial osteochondromatosis may be misinterpreted in some instances as chondrosarcoma, and thus a true rate of malignant degeneration is uncertain 4.

Treatment of synovial osteochondromatosis usually consists of removal of the intra-articular bodies with or without synovectomy, but local recurrence is not uncommon, occurring in ~12.5% (range 3-23%) of cases 4.

Primary synovial osteochondromatosis

Primary synovial osteochondromatosis also known as primary synovial chondromatosis, Reichel syndrome or Reichel-Jones-Henderson syndrome, is a benign monoarticular disorder of unknown origin that is characterized by synovial metaplasia and proliferation resulting in multiple intra-articular cartilaginous loose bodies of relatively similar size, not all of which are ossified. Hence, the term synovial chondromatosis is preferred over primary synovial osteochondromatosis. It is distinct from secondary synovial chondromatosis that is the result of a degenerative change in the joint.

The age range of affected patients is wide, but most present in the 4th or 5th decades of life 5. Men are affected more frequently (M:F ratio of 2:1 to 4:1) 6.

Primary synovial osteochondromatosis is a self-limiting benign neoplastic process 7 characterized by proliferative chondroid nodules of the synovium. Three phases of articular disease have been identified:

- Initial phase: metaplastic formation of cartilaginous nodules in the synovium

- Transitional phase: detachment of those nodules and formation of free intra-articular bodies

- Inactive phase: resolution of synovial proliferation, but loose bodies remain in the joint, and may increase in size obtaining nourishment from the joint fluid by diffusion

Usually, primary synovial osteochondromatosis is monoarticular affecting any joint but the large joints are preferentially affected:

- knee (up to 70%) 3

- hip (20%)

- elbow

- shoulder

Occasionally, bursa or tendon sheaths may be involved 8.

Secondary synovial osteochondromatosis

Secondary synovial osteochondromatosis is a disorder that results in intra-articular loose bodies as a result of trauma, osteoarthrosis, or neuropathic arthropathy. It is quite distinct to primary synovial osteochondromatosis. Pathologically concentric rings of growth may be seen.

Secondary osteochondromatosis typically demonstrates associated and more prominent changes of the underlying degenerative disease of the joint. Any intra-articular bodies tend to be larger, less numerous, and more varied in size and shape than in primary synovial osteochondromatosis.

Synovial osteochondromatosis causes

The cause of the primary synovial osteochondromatosis has not been determined. Elevated levels of bone morphogenic protein in the loose body lesions and the affected synovial joints of patients with primary synovial chondromatosis have been documented 1. However, the etiological importance of this has not been determined. Similarly, elevated levels of interleukin-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor-A have been found in these joints, but the importance of these findings is not certain. Secondary synovial osteochondromatosis is felt to occur as a result of mechanical changes in a joint due to arthropathy. The formation of loose chondral bodies is thought to be part of the degenerative process in these joints. It is not inherited.

Synovial osteochondromatosis pathophysiology

X-ray examination reveals irregularly shaped loose bodies within a synovial joint. This number varies anywhere from two or three loose bodies to several dozens. They present in varied sizes and several loose bodies may combine to form larger bodies. The number of intraarticular lesions is greater in the primary type than the secondary type. The gross and microscopic evaluation of the loose bodies reveals lobulated masses of hyaline cartilage surrounded by a layer of synovial tissue. The hyaline cartilage is hypercellular, and the cells are often atypical. These atypical changes are multinucleated cells, myxoid degeneration of matrix, crowding of cell nuclei and large nuclei. In long-standing disease, the lobules can undergo peripheral ossification. High levels of bone morphogenic protein have been found in the loose cartilaginous bodies and synovial tissue. The loose bodies may create pathological mechanical wear on joint surfaces and result in various types of erosion of articular surfaces. The process is classified as a benign neoplastic rather than a metaplastic lesion.

Synovial osteochondromatosis symptoms

Patients typically present with joint pain as a chief complaint. This usually is coupled with complaints of joint swelling. It most frequently is monoarticular in the primary form and may be multi-articular in the secondary form. Occasionally the patient will experience locking or catching in the joint. Pain is increased with weight bearing and may also be present at rest. In the secondary form, a history of osteoarthritis, post-traumatic arthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis may be present. Joint effusion may increase with increased activity. With increased joint effusions, pain can also increase.

The most common symptoms of synovial osteochondromatosis are similar to those of osteoarthritis. These include:

- Joint pain

- Joint swelling

- Limited range of motion in the affected joint

Other signs and symptoms may include:

- Fluid in the joint

- Tenderness

- A creaking, grinding, or popping noise during movement (crepitus)

The nodules can sometimes be felt in joints that are close to the skin, such as the knee, ankle, and elbow joints.

Synovial osteochondromatosis diagnosis

Your doctor will talk with you about your general health and medical history and ask about your symptoms. He or she will then carefully examine the affected joint, looking for:

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Creaking or grinding noises during movement, an indication of bone-on-bone friction

Imaging studies

Your doctor will order imaging studies to help diagnose synovial osteochondromatosis. Imaging studies will also help your doctor differentiate synovial osteochondromatosis from osteoarthritis.

- X-rays. X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Larger loose bodies are usually calcified or ossified and can be seen on x-ray. Smaller loose bodies and those that are not calcified or ossified may not show up.

- Other imaging studies. If the loose bodies are not visible on x-ray, your doctor may order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan or computerized tomography (CT) scan to better evaluate the joint. Loose bodies can typically be seen on both MRI and CT scans.

In addition to showing the loose bodies, imaging tests can also help your doctor determine whether you have any additional problems, such as fluid in the joint or signs of osteoarthritis (narrowing of the joint space and bone spurs).

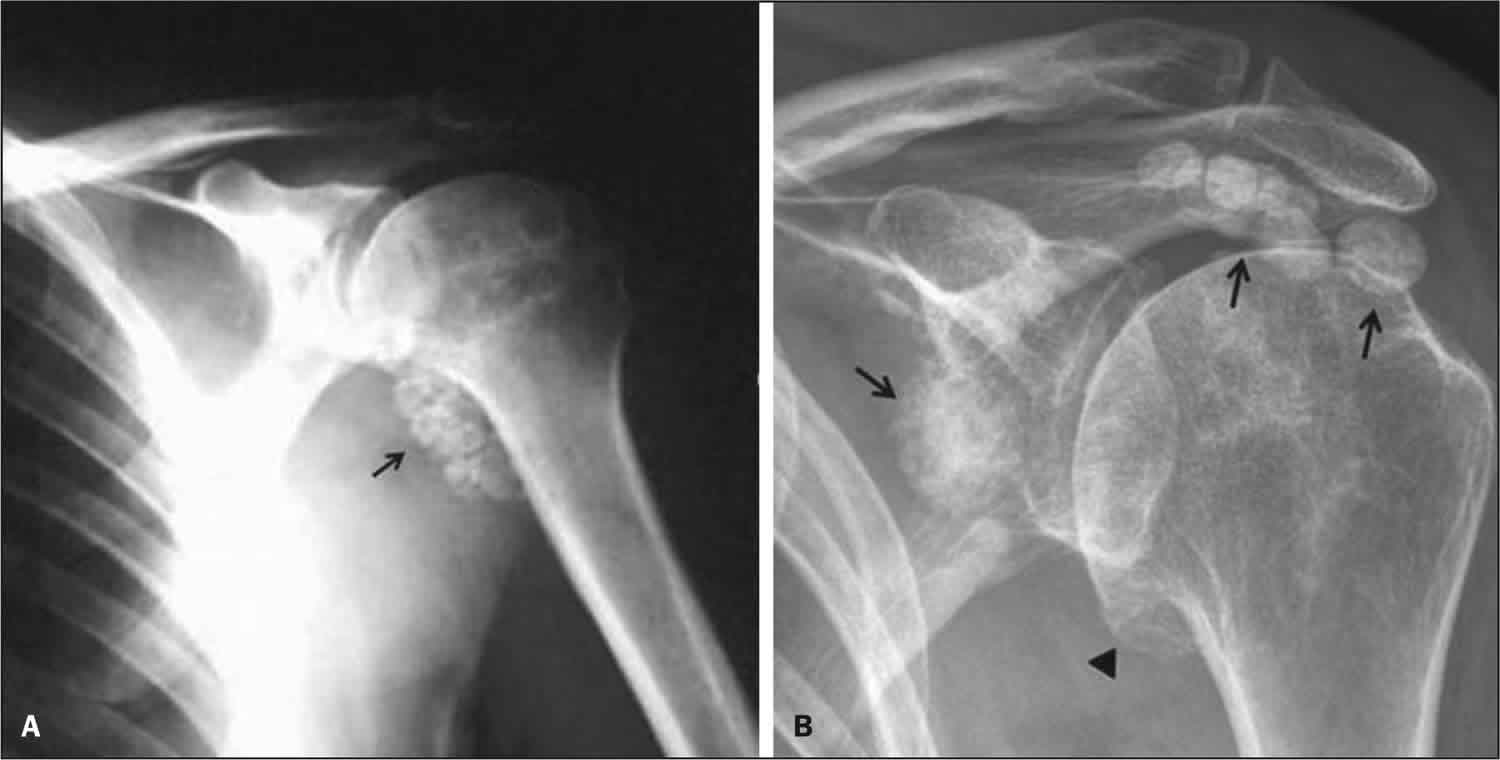

Figure 1. Synovial osteoosteochondromatosis shoulder

Footnote: The left shoulder shows multiple, juxtarticular, rounded calcifications which are similar in size and shape.

Figure 2. Synovial osteoosteochondromatosis MRI

Footnote: There are numerous similar-sized intra-articular loose bodies of variable signal intensity, some of them are showing intermediate to high signal intensity that is of cartilage. Others have low signal intensity at the periphery, which represents ossification. The joint capsule is distended with a little fluid and these numerous loose bodies. No significant degenerative changes of the joint.

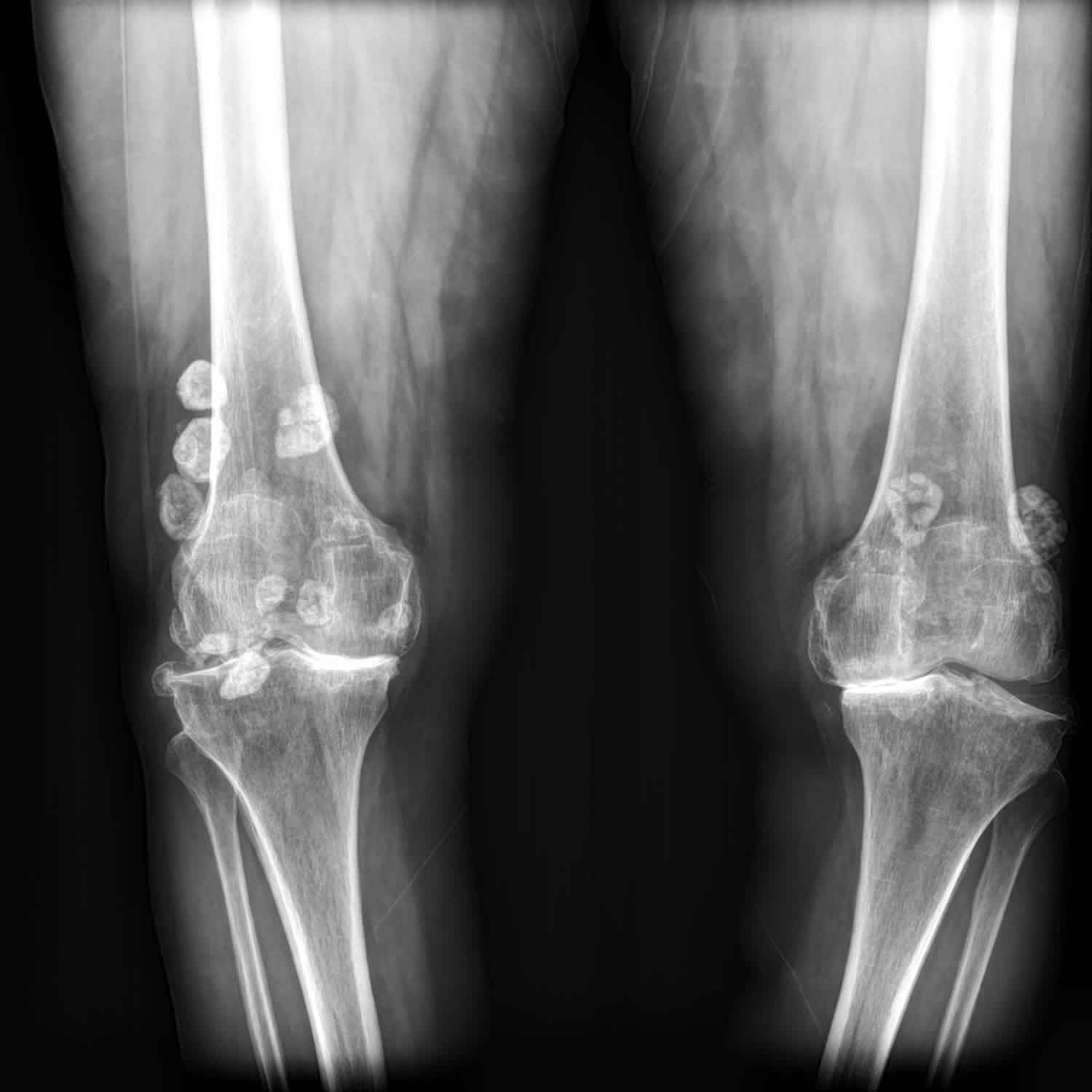

Figure 3. Synovial osteoosteochondromatosis knee

Footnote: Multiple intra-articular calcified loose bodies are present, bilaterally. Severe degenerative changes as joint space narrowing, sub-chondral sclerosis and osteophyte formation are also evident which are more prominent at medial sides of both knees.

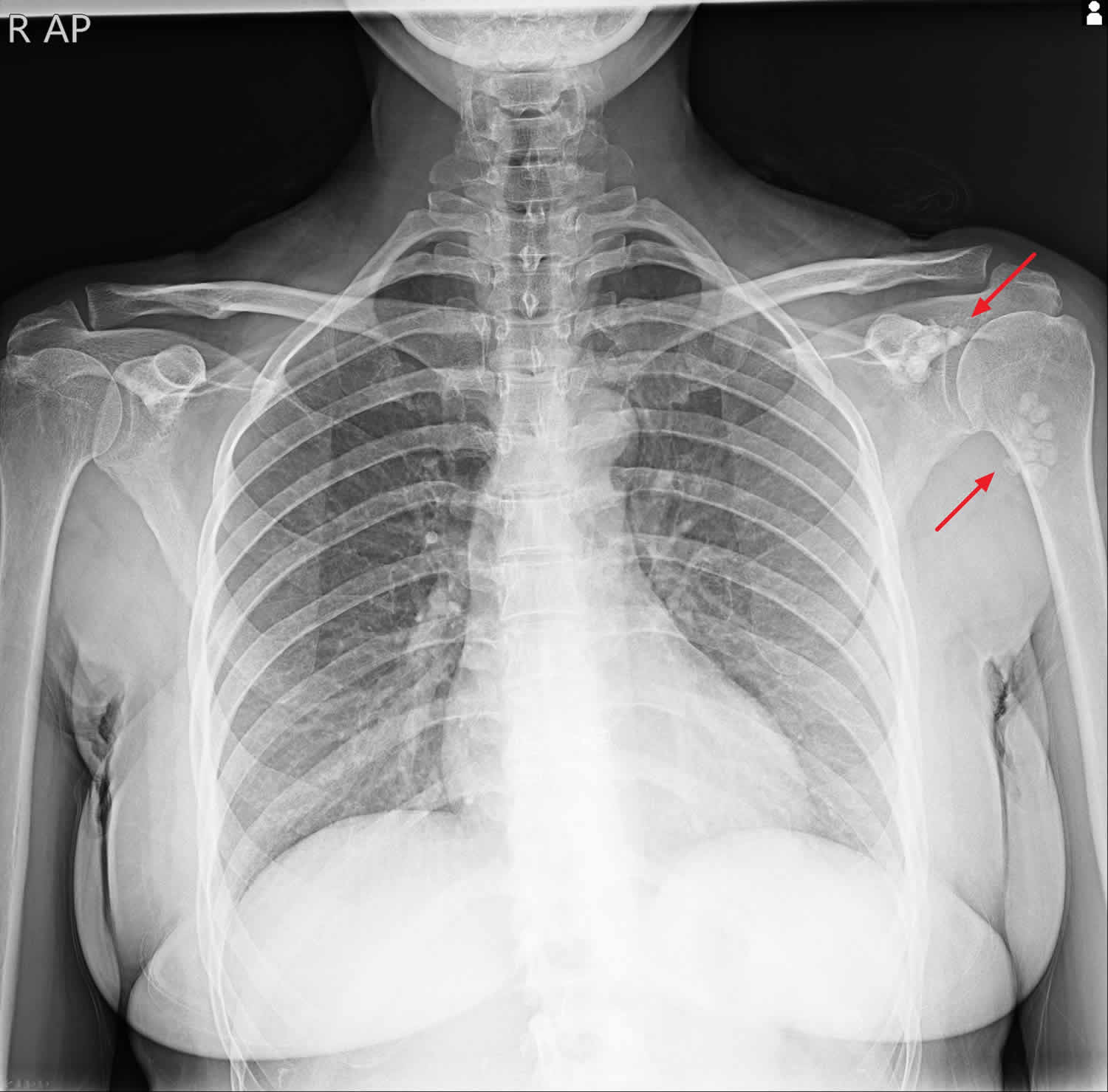

Figure 4. Synovial osteochondromatosis hip

Footnote: 30 year old male with persistent left hip pain, decreased range of motion, and limp. Remote childhood trauma. Innumerable small, well defined, uniform calcified opacities are noted along the joint capsule of the left hip.

Macroscopic appearance

Macroscopic appearance is that of a multilobulated synovium with multiple white/bluish nodules that are composed of hyaline cartilage attached to the synovium. These nodules may detach to form loose bodies. Most nodules are small (less than 2-3 cm) and usually uniform in size. Cases of massive nodules have been reported, with multiple nodules coalescing into giant nodules measuring up to 20 cm in size 4.

Histology

Microscopically the metaplastic synovium demonstrates cartilaginous nodules beneath the surface lining of the synovial membrane. They are characterized by proliferation and metaplastic transformation of the synovium, with formation of multiple cartilaginous or osteocartilaginous nodules within the joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths. These nodules are highly cellular, and the moderate pleomorphism may be identified. Cartilaginous bodies may contain cartilage alone, cartilage and bone, or mature bone with fatty marrow.

Synovial osteochondromatosis treatment

Management of primary synovial osteochondromatosis is surgery 1. Current arthroscopic surgical techniques allow for arthroscopic surgical management, however, occasionally open procedures may be necessary. Removal of loose bodies with partial synovectomy of the involved joints results in decreased pain, improved mechanical function, and decreased swelling in most cases. Open procedures have similar results, but surgical morbidity is greater. Post-operative management includes a progressive range of motion and strengthening of peri-articular muscle groups. The use of post-operative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication is not confirmed as being beneficial. Rare re-occurrence is reported following surgical management with partial synovectomy.

Secondary synovial osteochondromatosis is managed by anti-inflammatory medication with the additional management of the inflammatory joint symptoms until or unless mechanical symptoms prohibit adequate function. At this point, surgical management is indicated. Surgical management should address improving long-term function and prognoses. As such, joint reconstruction or arthroplasty in addition to removal of loose bodies is indicated.

Nonsurgical treatment

Observation. Depending on your symptoms, simple observation can sometimes be a treatment option. Your doctor will carefully consider a number of factors in determining whether observation is appropriate in your case.

During this time, your doctor will closely monitor the affected joint to check for the progression of osteoarthritis.

Surgical treatment

Treatment for synovial osteochondromatosis typically involves surgery to remove the loose bodies of cartilage. In some cases, the synovium is also partially or fully removed (synovectomy) during surgery.

Surgery can be done using either an open procedure or an arthroscopic procedure. The technique your doctor uses will depend upon a number of factors, including:

- The number of loose bodies

- The size of the loose bodies

- The condition of the synovium

- In a traditional open procedure, the doctor will usually make one or two large incisions.

In an arthroscopic procedure, the doctor will make smaller incisions and use miniature surgical tools to remove the loose bodies.

The end results of both open and arthroscopic procedures are the same. Your doctor will talk with you about which surgical technique is best in your case.

Recovery from surgery

How long it takes to return to your daily activities will vary, depending on the type of procedure you have. Your doctor will provide you with specific instructions to guide your rehabilitation.

Synovial osteochondromatosis may return in up to 20 percent of patients. For a period of time after surgery, your doctor will schedule regular follow-up visits to check for any recurrence.

Your doctor will also monitor the joint for any progression of osteoarthritis. The amount of damage synovial osteochondromatosis has already done to the joint will influence your chance of developing osteoarthritis.

Synovial osteochondromatosis prognosis

There is rarely reoccurrence of primary synovial osteochondromatosis after surgical management with the removal of the loose bodies and partial synovectomy. Reoccurrence has been reported in a case involving the temporal mandibular joint 1.

- Habusta SF, Tuck JA. Synovial Chondromatosis. [Updated 2020 Jun 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470463[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Littrell LA, Inwards CY, Rose PS, Wenger DE. Chondrosarcoma arising within synovial chondromatosis of the lumbar spine. Skeletal Radiol. 2019 Sep;48(9):1443-1449.[↩]

- Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: a clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(7):683-688. doi:10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90276-3[↩][↩]

- Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007;27(5):1465-1488. doi:10.1148/rg.275075116[↩][↩][↩]

- Kiritsi O, Tsitas K, Grollios G. A case of idiopathic bursal synovial chondromatosis resembling rheumatoid arthritis. Hippokratia. 2009;13(1):61-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2633259[↩]

- Narváez JA, Narváez J, Ortega R, De Lama E, Roca Y, Vidal N. Hypointense synovial lesions on T2-weighted images: differential diagnosis with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(3):761-769. doi:10.2214/ajr.181.3.1810761[↩]

- Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-smith JC et-al. Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 27 (5): 1465-88. doi:10.1148/rg.275075116[↩]

- Greenspan A. Orthopedic imaging, a practical approach. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (2004) ISBN:0781750067[↩]