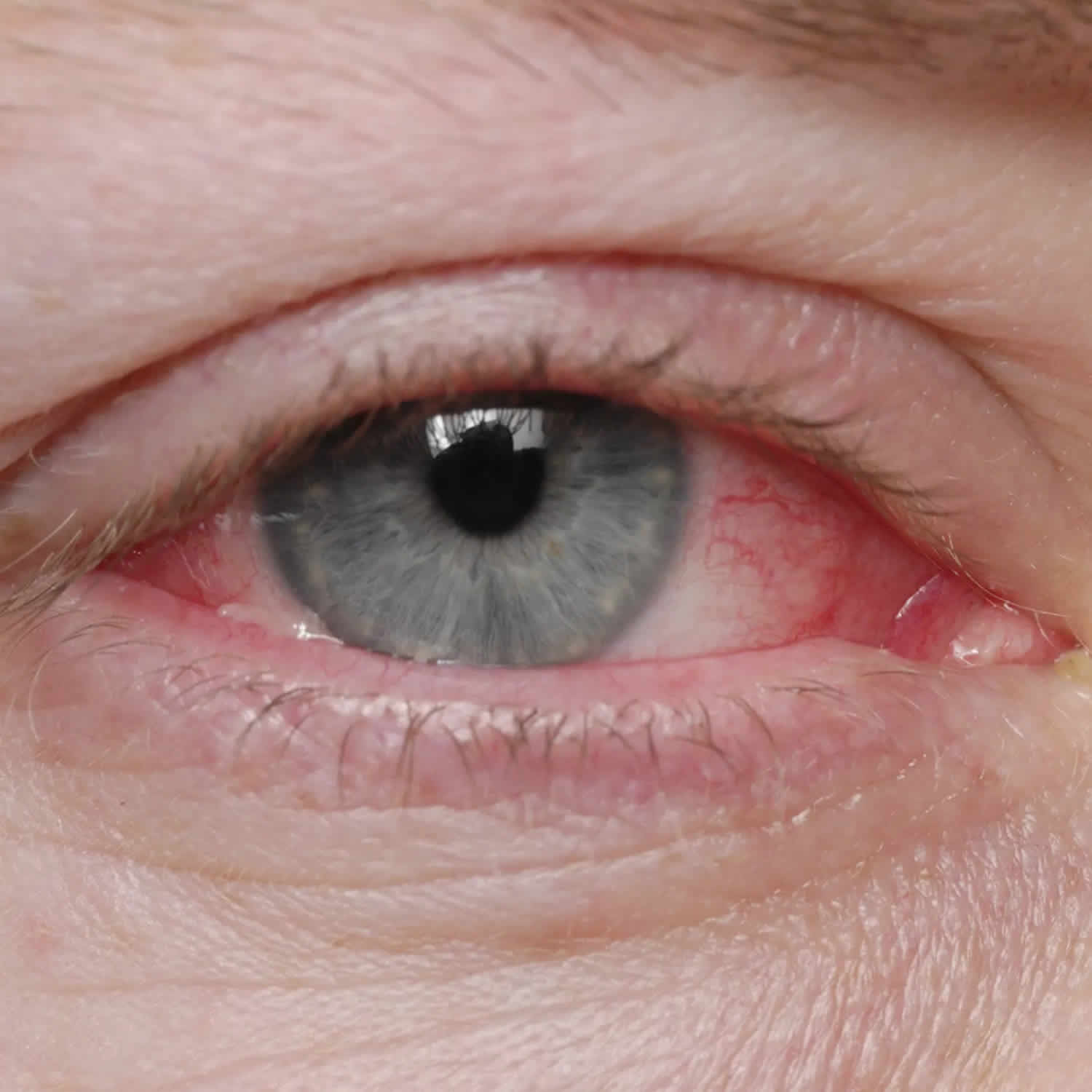

Viral conjunctivitis

Viral conjunctivitis is conjunctivitis caused by viruses and is very contagious. Virus is the most common cause of infectious conjunctivitis in the adult population (80%) and is more prevalent in the summer 1, 2. Viral conjunctivitis may involve one or both eyes, causing red itchy eyes with a ‘watery’ discharge, redness, blood vessel engorgement, pain, photophobia, and pseudomembranes 3. Viral conjunctivitis is highly contagious and means you are likely to have come into contact with someone who already has conjunctivitis. Sometimes viral conjunctivitis is accompanied by cold or flu symptoms. Children are most susceptible to viral infections, and adults tend to get more bacterial infections.

Viral conjunctivitis symptoms include:

- red, sore, watery or gritty eyes

- itchy and swollen eyes

- crusty eyelids.

Between 65% and 90% of cases of viral conjunctivitis are caused by adenoviruses. The adenovirus is part of the Adenoviridae family that consists of a nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus. Frequently associated infections caused by the adenovirus include upper respiratory tract infections (URTI), eye infections, and diarrhea in children. Viral conjunctivitis caused by adenoviruses produce two of the common clinical entities: pharyngoconjunctival fever, and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis 4.

- Pharyngoconjunctival fever is characterized by abrupt onset of high fever, pharyngitis, and bilateral conjunctivitis, and by periauricular lymph node enlargement.

- Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is more severe and presents with watery discharge, hyperemia, chemosis, and ipsilateral periauricular lymphadenopathy. Lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph glands) is observed in up to 50% of viral conjunctivitis cases and is more prevalent in viral conjunctivitis compared with bacterial conjunctivitis.

- Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis

- Acute follicular conjunctivitis

Viral conjunctivitis secondary to adenoviruses is highly contagious, and the risk of transmission has been estimated to be 10-50% 4. Incubation and communicability are estimated to be 5-12 days and 10-14 days, respectively 4.

Viral conjunctivitis secondary to herpes simplex virus (HSV) also known as herpes comprises 1.3-4.8% of all cases of acute conjunctivitis and is usually unilateral 5, 4. Primary herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-l) infection in humans occurs as a non-specific upper respiratory tract infection. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) spreads from infected skin and mucosal epithelium via sensory nerve axons to establish latent infection in associated sensory cranial nerve 5 (trigeminal nerve) and its ganglia. Latent infection of the trigeminal ganglion occurs in the absence of recognized primary infection, and reactivation of the virus may follow any of the three branches.

There is no specific treatment for most viral conjunctivitis and it usually will get better on its own.

Figure 1. Viral conjunctivitis

Viral conjunctivitis causes

The most common cause of viral conjunctivitis is adenoviruses. The adenovirus is part of the Adenoviridae family that consists of a nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus. Frequently associated infections caused by the adenovirus include upper respiratory tract infections, eye infections, and diarrhea in children.

Viral conjunctivitis can be contracted by direct contact with the virus, airborne transmission, and reservoir such as swimming pools 6, 7.

Most cases of viral conjunctivitis are highly contagious for 10-14 days. Washing hands and avoidance of eye contact are key to preventing transmission to others.

Up to 90% of viral conjunctivitis cases are caused by adenoviruses 8. In children pharyngoconjunctival fever due to human adenovirus (HAdV) types 3, 4, and 7 results in acute follicular conjunctivitis with fever, sore throat (pharyngitis) and periauricular lymphadenopathy 3. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is the most severe eye infection caused by adenovirus and is classically associated with human adenovirus (HAdV) serotypes 8, 19, and 37 3. The cornea can be affected by the viral replication in the epithelium and anterior stroma leading to superficial punctate keratopathy and subepithelial infiltrates 9.. Monotherapy with povidone-iodine 2% have demonstrated the resolution of symptoms 10. Further combinations of povidone-iodine with corticosteroids are undergoing phase 3 randomized controlled studies 3. Visual symptoms caused by subepithelial infiltrates can be debilitating and the use of tacrolimus, 1% and 2% cyclosporine A eye drops have been shown to effective 11, 12, 13.

Herpetic conjunctivitis

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is estimated to be responsible for 1.3 – 4.8% of acute conjunctivitis cases 5. Herpes conjunctivitis is common in adults and children and associated with follicular conjunctivitis. Herpetic conjunctivitis treatment with topical antiviral agents is aimed at reducing virus shedding and the development of keratitis.

Varicella-zoster virus

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), a virus that causes chickenpox or varicella, can cause conjunctivitis either by direct contact of the eye or skin lesions or inhalation of infected aerosolized particles, especially with the involvement of the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve.

Acute Hemorrhagic Conjunctivitis (AHC)

Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis (AHC) is a very contagious form of viral conjunctivitis and symptoms include foreign body sensation, epiphora, eyelid edema, conjunctival chemosis, and subconjunctival hemorrhage 3. A small proportion of patients experience systemic symptoms of fever, fatigue, limb pain. Picornaviruses EV70 and coxsackievirus A24 variant (CA24v) are thought to be the responsible viruses 14. Transmission is primarily via hand to eye contact and fomites 15.

Figure 2. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis

Footnotes: Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis caused by coxsackievirus A24 variant (CA24v) infection. (A) First day morning; (B) first day afternoon; (C) second day am; (D) second day pm; (E) third day am; (F) fourth day pm; (G) sixth day pm. The bilateral lid edema (*), vascular dilation, and conjunctival erythema were noted on the second day, and the inferior-nasal chemosis (arrow) was present on the third day post-acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. The clinical signs were less and resolved more quickly in the right (second infected) than the left (first affected) eye.

[Source 15 ]COVID-19 conjunctivitis

COVID-19 has been reported to cause conjunctivitis along with fever, cough, respiratory distress, and death 16. Retrospective and prospective studies show that 1% to 6% of patients display COVID-19 related conjunctivitis, with conjunctival swabs being positive in 2.5% of cases 17. Transmission through ocular tissues is incompletely understood. Ophthalmologists are at higher risk for COVID-19 infection due to the close proximity to patients, equipment intense clinics, direct contact with patients’ conjunctival mucosal surfaces, and high-volume clinics. Systemic COVID-19 is contracted through direct or airborne inhalation of respiratory droplets. Additional protective measures such as social distancing, wearing masks, reduced clinic volumes, and sterilization of surfaces should be practiced to reduce transmission risk.

Viral conjunctivitis signs and symptoms

Viral conjunctivitis can lead to one or more of these symptoms:

- eye irritation and redness

- excessive tearing from eyes

- discharge from the eyes

- swelling of the eyelids

- photophobia (unable to tolerate looking into light)

- often associated with an upper respiratory tract infection (cold).

Patients with viral conjunctivitis present with sudden onset foreign body sensation, red eyes, itching, light sensitivity, burning, and watery discharge. Whereas with bacterial conjunctivitis, patients present with all the above symptoms, but with pus (mucopurulent discharge) and sticky eyelids upon waking.

Visual acuity is usually at or near their baseline vision. The cornea can have subepithelial infiltrates that can decrease the vision and cause light sensitivity. The conjunctiva is injected (red) and can also be edematous. In some cases, a membrane or pseudomembrane can be appreciated in the tarsal conjunctiva. These are sheets of fibrin-rich exudates that are devoid of blood or lymphatic vessels. True membranes can lead to the development of subepithelial fibrosis and symblepharon, and also bleed heavily on removal 18. Follicles, small, dome-shaped nodules without a prominent central vessel, can be seen on the palpebral conjunctiva. The majority of viral conjunctivitis patients will have follicles present, but the presence of papillae does not rule out a viral etiology 19.

Fever, malaise, fatigue, presence of enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) and other constitutional signs help to differentiate viral conjunctivitis from other causes. Unequal pupil size (anisocoria) and photophobia are associated with serious eye conditions including anterior uveitis, keratitis, and scleritis 20.

When primary eye herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection occurs, the patient typically manifests unilateral, thin, and watery discharge and sometimes vesicles may appear on the face or eyelids and vision may be affected. Corneal involvement may occur. With herpes zoster, there is a linear dermatomal pattern of vesicles. The conjunctiva is often red with a mucopurulent discharge. In a small percentage of patients, there is a history of external eye HSV infection that may lead to the diagnosis.

Conjunctivitis caused by adenoviruses:

- Pharyngoconjunctival fever presents by abrupt onset of high fever, pharyngitis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, bilateral conjunctivitis, and by preauricular lymph node enlargement.

- Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is more severe and presents with watery discharge, conjunctival membranes or pseudo membranes, hyperemia, chemosis, and ipsilateral preauricular lymphadenopathy. Can involve both epithelial and subepithelial corneal infiltrates.

- Can affect the cornea, look for subepithelial infiltrates.

- Lymphadenopathy is observed in up to 50% of viral conjunctivitis cases and is more prevalent in viral conjunctivitis compared with bacterial conjunctivitis.

Herpes virus conjunctivitis:

- The eyelids often are swollen with small bruise. Watery discharge and lymphadenopathy in front of the ear may be present. Usually unilateral.

- Skin or eyelid margin vesicles, or ulcers on the bulbar conjunctiva

- The cornea often demonstrates a punctate epitheliopathy. In severe cases, there can be a corneal epithelial defect (Dendritic epithelial keratitis). It typically begins in one eye and progresses to the fellow eye over a few days.

- It is important to note that herpes virus conjunctivitis does not form conjunctival membranes or pseudo membranes.

- Herpes zoster virus can involve ocular tissue, especially if the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerve are involved. Eyelids (45.8%) are the most common site of ocular involvement, followed by the conjunctiva. Corneal complication and uveitis may be present in 38.2% and 19.1% of cases, respectively. Severe forms include those presenting with the Hutchinson sign (vesicles at the tip of the nose, which has a high correlation with corneal involvement).

Viral conjunctivitis complications

Viral conjunctivitis complications may include 3:

- Punctate keratitis

- Bacterial superinfection

- Conjunctival scarring

- Corneal ulceration

- Chronic infection

Viral conjunctivitis diagnosis

In most cases, your doctor can diagnose viral conjunctivitis by asking about your recent health history and symptoms and examining your eyes. Palpation of the preauricular lymph nodes may reveal a reactive lymph node that is tender to the touch and will help differentiate viral conjunctivitis versus bacterial conjunctivitis.

Viral conjunctivitis secondary to adenoviruses is highly contagious, and the risk of transmission has been estimated to be 10-50%. Patients commonly report recent contact with an individual with a red eye, or they may have a history of recent symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Incubation and communicability are estimated to be 5-14 days for viral conjunctivitis secondary to adenoviruses.

Laboratory testing is typically not indicated unless the symptoms are not resolving and infection last longer than 4 weeks 3. Laboratory testing can be indicated in certain situations such as a suspected chlamydial infection in a newborn, an immune-compromised patient, excessive amounts of discharge, or suspected gonorrhea co-infection 3. In the office, doctors can run tests to positively identify adenovirus with a specificity and sensitivity of 89% and 94%, respectively. However, ophthalmologists usually can make the diagnosis clinically with confirmational additional testing 21.

Regarding adenovirus testing, the gold standard has traditionally been cell culture because once the virus is isolated, the diagnosis is definitive and the characterization of the virus can be undertaken 22. Disadvantages include cost and increased time associated with cell culture-based testing. The mainstay of viral conjunctivitis testing in the developed world is the detection of viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR for adenovirus has been shown to be 93% sensitive and 97.3% specific from conjunctival swabs, with similar values, found for HSV diagnosis 22. A recent development has been the creation of a rapid detection testing platform for adenovirus, the AdenoPlus assay (Rapid Pathogen Screening Inc., Sarasota, Florida, USA). This is a swift office-based test designed to detect 53 serotypes of adenovirus and provide a result within 10 minutes 23. Studies have demonstrated high specificity values of 92% to 98% in detecting adenoviral conjunctivitis 24, 25, 26. However, the test has lower sensitivity reported compared with PCR analysis 24, 25, 26. Rapid detection testing can be more useful in the future once viral conjunctivitis treatments reach the clinical setting 27.

Viral conjunctivitis treatment

Viral conjunctivitis treatment is aimed at symptomatic relief and not to eradicate the self-limiting viral infection 3. The resolution of viral conjunctivitis can take up to 3 weeks. Treatment includes using artificial tears for lubrication four times a day or up to ten times a day with preservative-free tears. Cool compresses with a wet washcloth to the periocular area may provide symptomatic relief. Preventing the spread of infection to the other eye or other people requires the patient to practice good hand hygiene with frequent washing, avoidance of sharing towels or linens, and avoiding touching their eyes. A person is thought to shed the virus while their eyes are red and tearing.

If a membrane or pseudomembrane is present, it can be peeled at the slit lamp to improve patient comfort and prevent any scar formation from occurring 3. These membranes can either be peeled with a jeweler forceps or a cotton swab soaked with topical anesthetic 3. Topical steroids can help with the resolution of symptoms. However, they can also cause the shedding of the virus to last longer. Patients should be informed that they are highly contagious and should refrain from work or school until their symptoms resolve. While using steroids, they may still shed the virus without the visual symptoms that would indicate that they have an infection. Steroids should be reserved for patients with decreased vision due to their subepithelial infiltrates or severe conjunctival injection causing more the expected discomfort 28, 29.

The use of povidone-iodine, a non-specific disinfectant, is a promising new treatment for adenoviral conjunctivitis 23. This is an inexpensive and widely available antiseptic solution which is used as part of the aseptic preparation for ocular surgery. It is able to kill extracellular organisms but has no effect intracellularly. It does not induce drug resistance because its mechanism of action is not immunologically dependent. A single dose of 2.5% povidone-iodine in infants with adenoviral conjunctivitis resulted in a reduction in symptom severity and reduced recovery time without significant side effects 30.

Topical corticosteroids alone are contraindicated in epithelial herpes simplex keratitis and are associated with prolonged viral shedding and infection 27. When used in combination with an anti-infective, corticosteroids have demonstrated good tolerability and efficacy in treating the inflammatory and infectious components of conjunctivitis 31, 32.

Viral conjunctivitis prognosis

The majority of cases of virus conjunctivitis resolve on their own 3. In rare cases, chronic infection may occur. Most cases resolve within 14-30 days. In some patients, photophobia, diminished vision and glare may be a problem 3.

- Keen M, Thompson M. Treatment of Acute Conjunctivitis in the United States and Evidence of Antibiotic Overuse: Isolated Issue or a Systematic Problem? Ophthalmology. 2017 Aug;124(8):1096-1098. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.029[↩]

- Udeh BL, Schneider JE, Ohsfeldt RL. Cost effectiveness of a point-of-care test for adenoviral conjunctivitis. Am J Med Sci. 2008 Sep;336(3):254-64. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181637417[↩]

- Solano D, Fu L, Czyz CN. Viral Conjunctivitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470271[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Conjunctivitis. https://eyewiki.org/Conjunctivitis[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, van Schayck CP, McLean S, Nurmatov U. Antibiotics versus placebo for acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep 12;(9):CD001211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001211.pub3. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Mar 13;3:CD001211. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001211.pub4[↩][↩]

- Li J, Lu X, Jiang B, Du Y, Yang Y, Qian H, Liu B, Lin C, Jia L, Chen L, Wang Q. Adenovirus-associated acute conjunctivitis in Beijing, China, 2011-2013. BMC Infect Dis. 2018 Mar 20;18(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3014-z[↩]

- Sow AS, Kane H, Ka AM, Hanne FT, Ndiaye JMM, Diagne JP, Nguer M, Sow S, Saheli Y, Sy EHM, De Meideros Quenum ME, Ndoye Roth PA, Ba EA, Ndiaye PA. Expérience sénégalaise des conjonctivites virales aiguës [Senegalese experience with acute viral conjunctivitis]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2017 Apr;40(4):297-302. French. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2016.12.008[↩]

- Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013 Oct 23;310(16):1721-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280318. Erratum in: JAMA. 2014 Jan 1;311(1):95. Dosage error in article text.[↩]

- Chigbu DI, Labib BA. Pathogenesis and management of adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Infect Drug Resist. 2018 Jul 17;11:981-993. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S162669[↩]

- Trinavarat A, Atchaneeyasakul LO. Treatment of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis with 2% povidone-iodine: a pilot study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Feb;28(1):53-8. doi: 10.1089/jop.2011.0082[↩]

- Levinger E, Slomovic A, Sansanayudh W, Bahar I, Slomovic AR. Topical treatment with 1% cyclosporine for subepithelial infiltrates secondary to adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2010 Jun;29(6):638-40. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181c33034[↩]

- Berisa Prado S, Riestra Ayora AC, Lisa Fernández C, Chacón Rodríguez M, Merayo-Lloves J, Alfonso Sánchez JF. Topical Tacrolimus for Corneal Subepithelial Infiltrates Secondary to Adenoviral Keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2017 Sep;36(9):1102-1105. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001279[↩]

- Arici C, Mergen B. Late-term topical tacrolimus for subepithelial infiltrates resistant to topical steroids and ciclosporin secondary to adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021 May;105(5):614-618. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316196[↩]

- Zhang L, Zhao N, Huang X, Jin X, Geng X, Chan TC, Liu S. Molecular epidemiology of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis caused by coxsackie A type 24 variant in China, 2004-2014. Sci Rep. 2017 Mar 23;7:45202. doi: 10.1038/srep45202[↩]

- Langford MP, Anders EA, Burch MA. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis: anti-coxsackievirus A24 variant secretory immunoglobulin A in acute and convalescent tear. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015 Sep 10;9:1665-73. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S85358[↩][↩]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):497-506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. Epub 2020 Jan 24. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):496. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30252-X[↩]

- Danesh-Meyer HV, McGhee CNJ. Implications of COVID-19 for Ophthalmologists. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar;223:108-118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.09.027[↩]

- Chintakuntlawar AV, Chodosh J. Cellular and tissue architecture of conjunctival membranes in epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010 Oct;18(5):341-5. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2010.498658[↩]

- Marinos E, Cabrera-Aguas M, Watson SL. Viral conjunctivitis: a retrospective study in an Australian hospital. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2019 Dec;42(6):679-684. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2019.07.001[↩]

- Narayana S, McGee S. Bedside Diagnosis of the ‘Red Eye’: A Systematic Review. Am J Med. 2015 Nov;128(11):1220-1224.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.026[↩]

- Sethuraman U, Kamat D. The red eye: evaluation and management. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009 Jul;48(6):588-600. doi: 10.1177/0009922809333094[↩]

- Elnifro EM, Cooper RJ, Klapper PE, Yeo AC, Tullo AB. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of viral and chlamydial keratoconjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000 Jun;41(7):1818-22.[↩][↩]

- Kaufman HE. Adenovirus advances: new diagnostic and therapeutic options. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011 Jul;22(4):290-3. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283477cb5[↩][↩]

- Kam KY, Ong HS, Bunce C, Ogunbowale L, Verma S. Sensitivity and specificity of the AdenoPlus point-of-care system in detecting adenovirus in conjunctivitis patients at an ophthalmic emergency department: a diagnostic accuracy study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Sep;99(9):1186-9. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306508[↩][↩]

- Sambursky R, Trattler W, Tauber S, Starr C, Friedberg M, Boland T, McDonald M, DellaVecchia M, Luchs J. Sensitivity and specificity of the AdenoPlus test for diagnosing adenoviral conjunctivitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Jan;131(1):17-22. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaophthalmol.513. Erratum in: JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013 Mar;131(3):320.[↩][↩]

- Holtz KK, Townsend KR, Furst JW, Myers JF, Binnicker MJ, Quigg SM, Maxson JA, Espy MJ. An Assessment of the AdenoPlus Point-of-Care Test for Diagnosing Adenoviral Conjunctivitis and Its Effect on Antibiotic Stewardship. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017 Jul 25;1(2):170-175. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.06.001[↩][↩]

- Jhanji V, Chan TC, Li EY, Agarwal K, Vajpayee RB. Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2015 Sep-Oct;60(5):435-43. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.04.001[↩][↩]

- Usher P, Keefe J, Crock C, Chan E. Appropriate prescribing for viral conjunctivitis. Aust Fam Physician. 2014 Nov;43(11):748-9.[↩]

- Shiota H, Ohno S, Aoki K, Azumi A, Ishiko H, Inoue Y, Usui N, Uchio E, Kaneko H, Kumakura S, Tagawa Y, Tanifuji Y, Nakagawa H, Hinokuma R, Yamazaki S, Yokoi N. [Guideline for the nosocomial infections of adenovirus conjunctivitis]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2009 Jan;113(1):25-46. Japanese.[↩]

- Özen Tunay Z, Ozdemir O, Petricli IS. Povidone iodine in the treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis in infants. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2015 Mar;34(1):12-5. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2014.888077[↩]

- Kovalyuk N, Kaiserman I, Mimouni M, Cohen O, Levartovsky S, Sherbany H, Mandelboim M. Treatment of adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis with a combination of povidone-iodine 1.0% and dexamethasone 0.1% drops: a clinical prospective controlled randomized study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017 Dec;95(8):e686-e692. doi: 10.1111/aos.13416[↩]

- Faraldi F, Papa V, Rasà D, Santoro D, Russo S. Netilmicin/dexamethasone fixed combination in the treatment of conjunctival inflammation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1239-44. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S44455[↩]