Vulvar itching

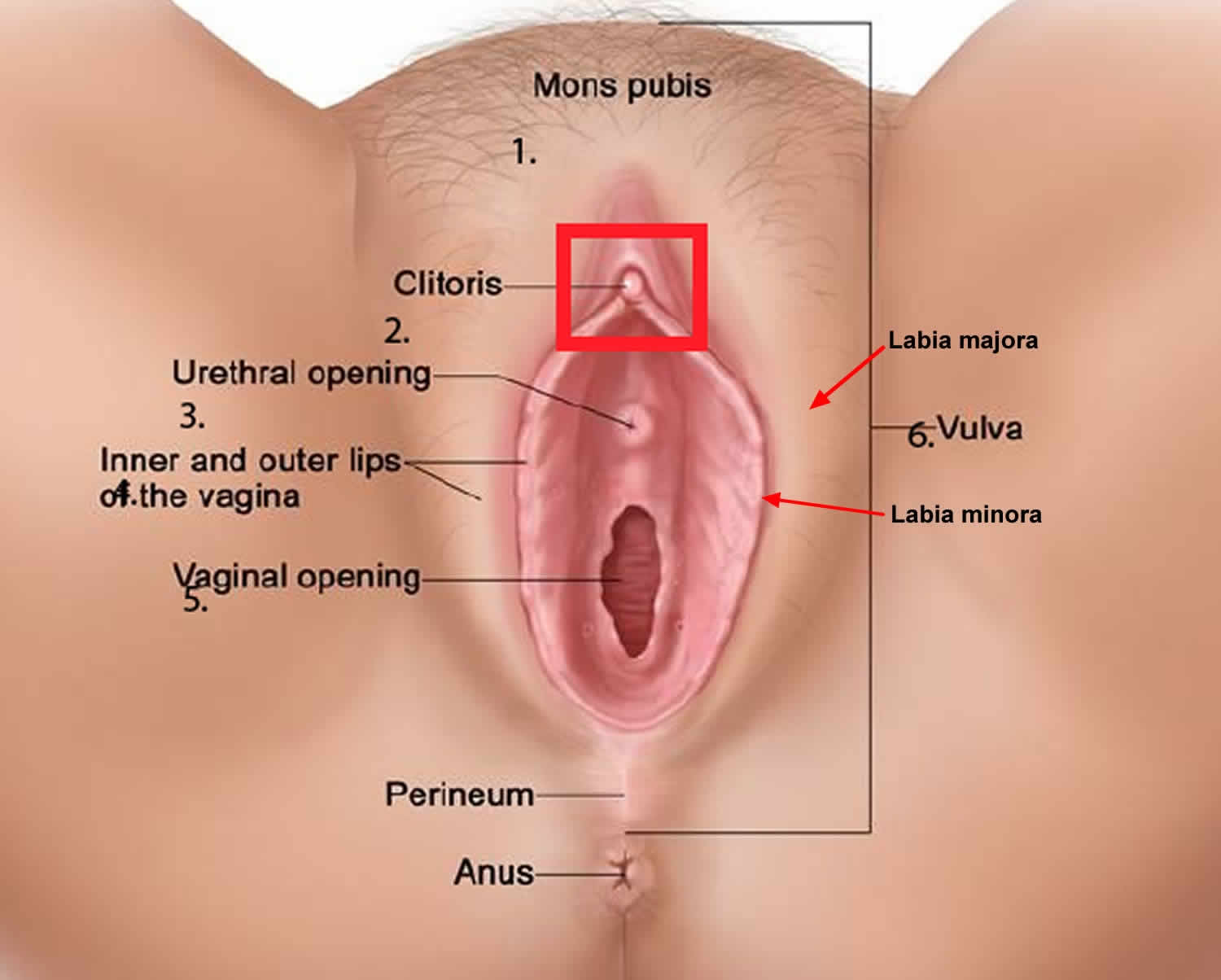

The vulva is the external female genital area, it includes the mons pubis, labia majora (outer lips), labia minora (inner lips), clitoris, perineum (the tissue between vagina and anus) and the external openings of the urethra and vagina.

Vulvar itching can be broadly classified into infective, dermatological and neoplastic causes. The sensation of itch in the vulva in the absence of a known skin condition is referred to as pruritus vulvae 1. Pruritus vulvae should be distinguished from vulval pain and from vulvodynia, which refers to chronic burning symptoms in the absence of clinical signs. Vulval itch, pain and burning can co-exist. In a sample of 141 women with long term (chronic) vulvar itching symptoms referred to a dermatologist, dermatitis was found to be the commonest cause 2. It is rare not to find a cause of pruritus vulvae; therefore a diagnosis of idiopathic vulvar itching can only be made when all possible causes have been excluded.

Girls and women of any age and race can experience mild, moderate or severe vulval itch, which can be intermittent or continuous. They may or may not have an associated skin condition.

Your health care professional may examine you, ask you questions about the pain and your daily routine, and take samples of vaginal discharge for testing. In some cases, a biopsy is needed to confirm diagnosis of a disease.

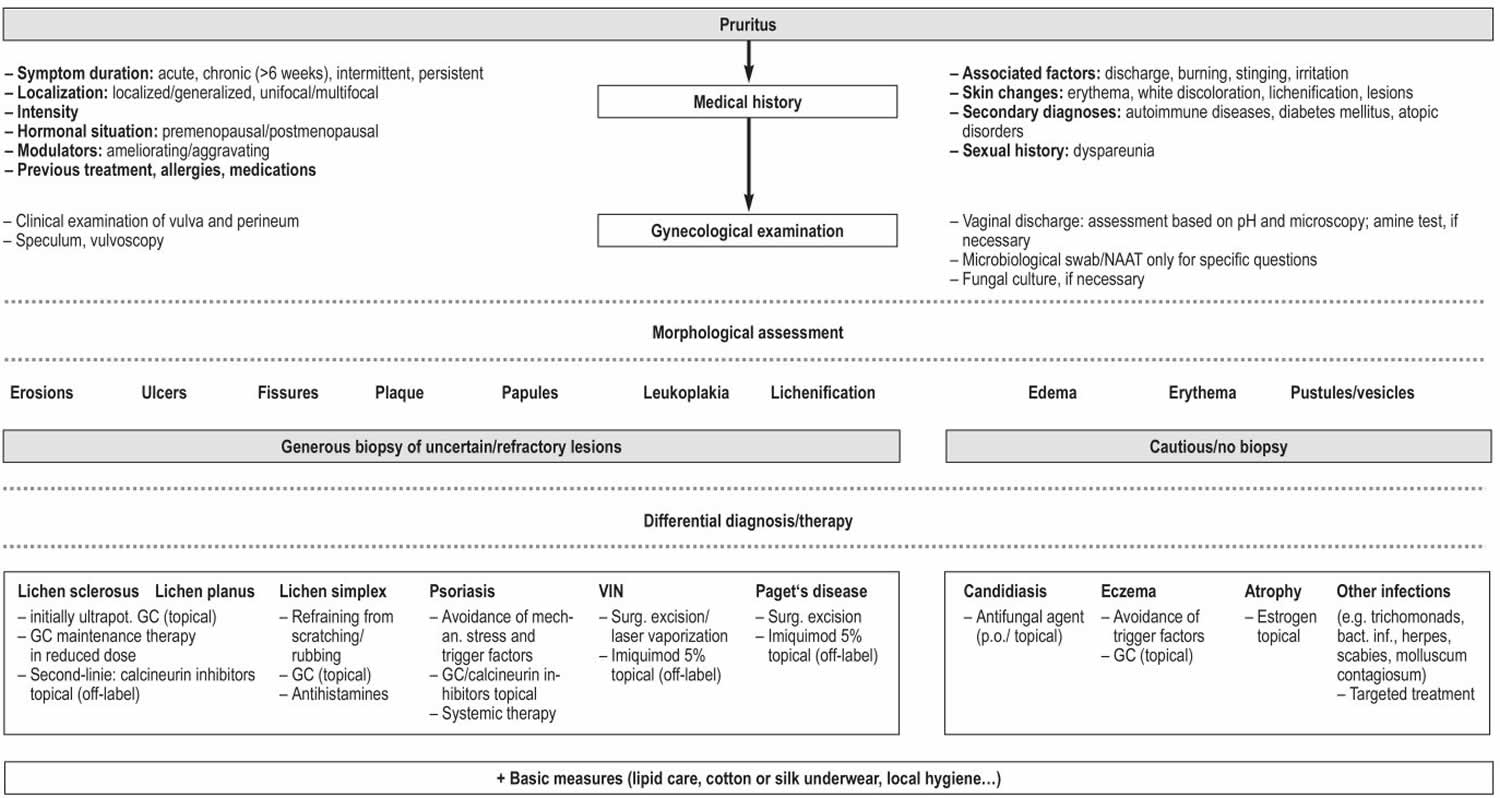

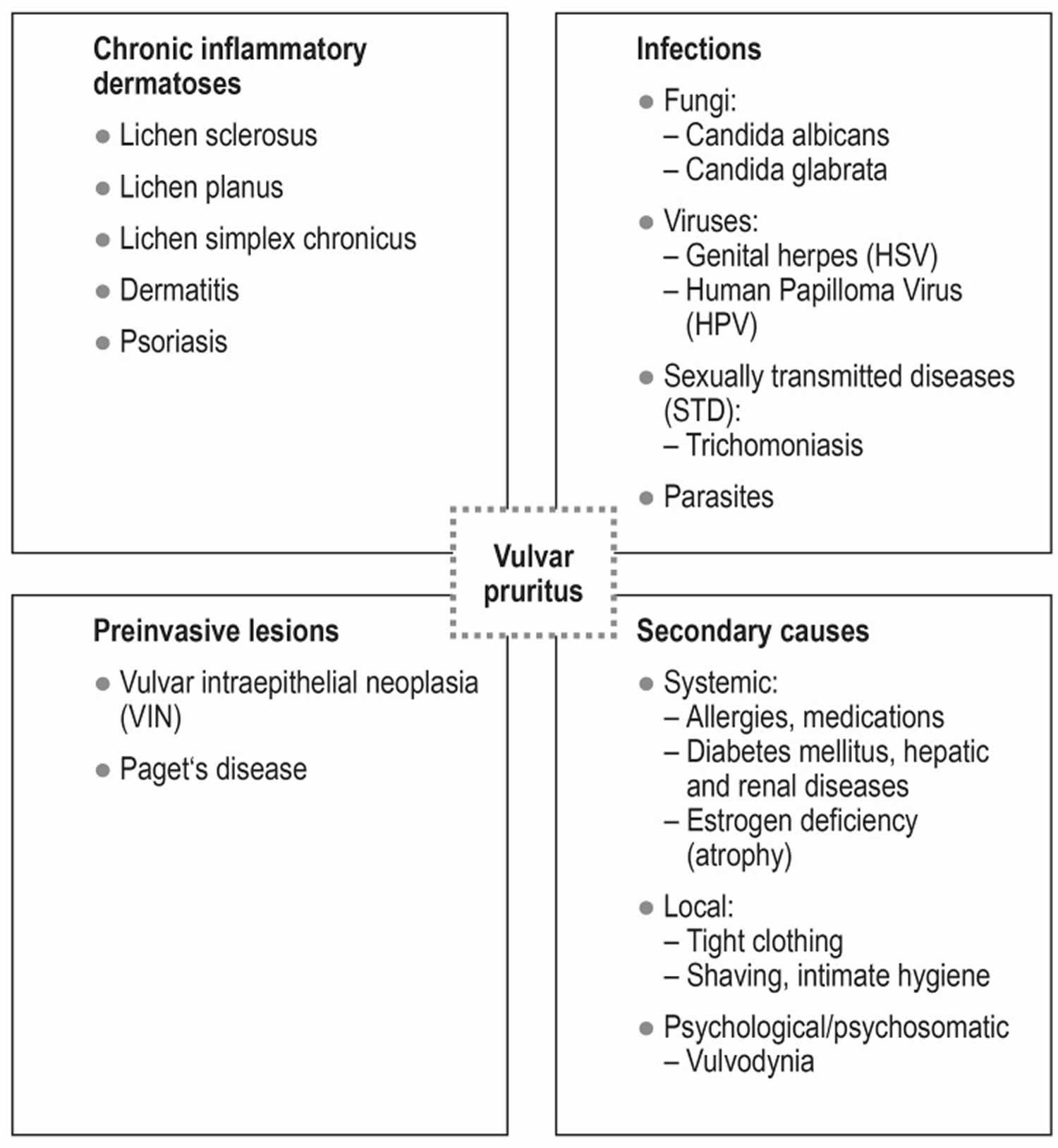

The most common cause of vulvar itching or vulvar pruritus is vulvovaginal candidiasis followed by chronic dermatoses, such as lichen sclerosus and vulvar eczema 3. Especially in refractory cases, an invasive or preinvasive lesion such as squamous epithelial dysplasia (VIN, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia) should be borne in mind in the differential diagnosis. Rarer causes include infection, atrophy, and vulvodynia. The essential elements of treatment are topical/oral antimycotic drugs and high-potency glucocorticoids, along with consistently applied, basic moisturizing care and the avoidance of potential triggering factors.

Figure 1. The vulva

Figure 2. Vulvar itching diagnostic algorithm

Footnote: Differential diagnostic work-up and diagnosis of vulvar pruritus by morphology.

Abbreviations: bact.= bacterial; surg. = surgical; ultrapot. = ultrapotent; GC = glucocorticoids; Inf. = infection; mechan. = mechanical; NAAT = nucleic acid amplification test; p.o. = per os /orally; VIN = vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

[Source 3 ]See a dermatologist or gynecologist if a cause is unclear; if symptoms persist despite treatment in primary care, or if a premalignant condition such as lichen sclerosus or lichen planus is suspected 4.

Urgently see a dermatologist or gynecologist for all women with a suspected vulval carcinoma (for example, an unexplained vulval lump or ulcer) 5.

Vulvar itching causes

One or more specific conditions may be the cause of a vulval itch. In the majority of cases a cause for pruritus vulvae is normally found and there is a very good chance the symptoms will improve if not disappear altogether with treatment, and general care of the vulva 6.

Figure 3. Vulvar itching causes

Footnote: Common differential diagnoses of vulvar pruritus.

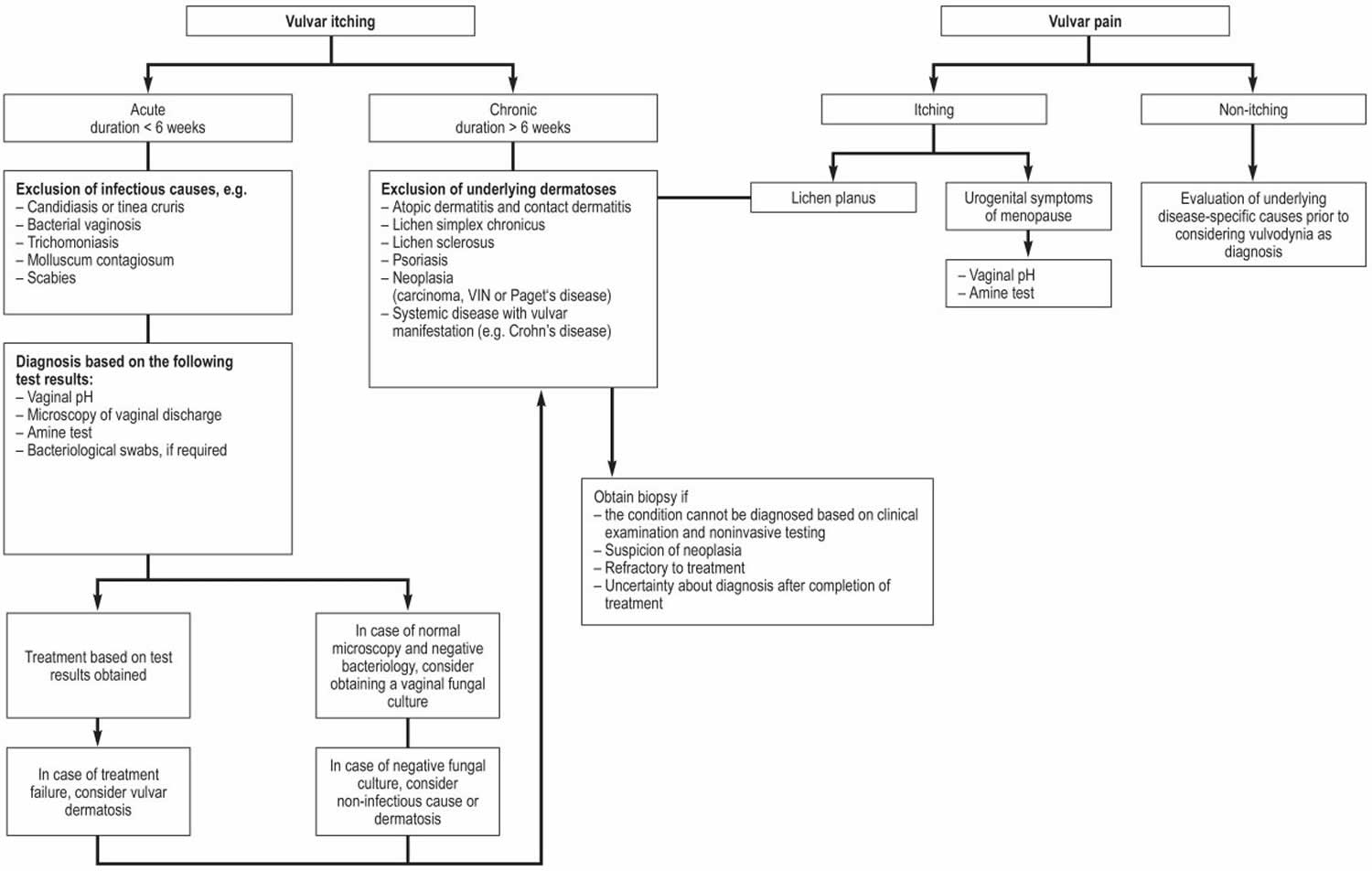

[Source 3 ]Figure 4. Vulvar itching differential diagnosis

Footnote: Differential diagnostic work-up and diagnosis of vulvar pruritus by symptom; VIN, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

Table 1. Vulvar itching differential diagnosis

| Candidiasis | Lichen sclerosus | Lichen planus | VIN (vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia) | Eczema | Psoriasis | |

| Frequency (prevalence) | 10–20% | 0.1–3% | 0.1–0.8% | Exact prevalence unknown, incidence Approx. 3/100 000 women in Germany | 0.5–10% | 2% |

| Morphological features | Red and white plaques, erosions, ulcers | – Early form: erythema, erosions– Late form: white, firm plaques, bleeding into skin, scarring, atrophy, fissures, exaggerated skin markings | – Early form: charact. whitish reticulate (Wickham) striae – Late form/erosive form: erosive erythema, scarring, extragenital involvement (e.g. oral) | Skin-colored papules and nodules, white and red plaques, acetowhite lesions (after application of 5% acetic acid), erosions (especially with differentiated VIN) | Poorly marginated erythematous lesions on the labia majora and labia minora, edema (acute), lichenification (chronic) | Well-demarcated, slightly scaly, erythematous red plaques, accompanying fissures and rhagades |

| Signs & symptoms | Pruritus, erythema, increased vaginal discharge (white, curd-like, no odor) | Pruritus, burning, dyspareunia | – Early form: pruritus, burning, pain– Late form: dyspareunia, burning, vaginal stenosis | Pruritus, burning, soreness, often asymptomatic | Pruritus, soreness | Pruritus |

| Diagnosis | pH value: normal (< 4.0) lactobacilli : yes leukocytes: increased clue cells: none microscopy: pseudomycelium & blastospores | History, clinical examination, typical figure-of-8 pattern surrounding the vulva and anus; histological confirmation by biopsy, if required | History, clinical examination, characteristic Wickham striae, vaginal involvement, histological confirmation by biopsy | Vulvoscopy, histological confirmation by biopsy | History, clinical examination; if necessary, patch test | Typical involvement of labia majora, characteristic non-involvement of labia minora |

| Management | – Acute: Antifungal agent (e.g. oral fluconazole or topical clotrimazole preparations) – Chronic: Following the initial treatment, fluconazole 150 mg orally 1 x/week for at least 6 months after loading dose | – Initially ultrapotent glucocorticoids (topical) – Life-long glucocorticoid maintenance dose in reduced dose, lipid replenishment – Second-line therapy: calcineurin inhibitors (off-label) | – Initially ultrapotent glucocorticoids (topical) – Life-long glucocorticoid maintenance dose in reduced dose, lipid replenishment –Second-line therapy: calcineurin inhibitors (off-label) | – Laser vaporization (standard with usual-type VIN) – Surgical excision rather with differentiated VIN (Warning: occult carcinoma) – Imiquimod 5%, topical for usual-type VIN (off-label) | – Avoidance of trigger factors – Glucocorticoids (topical) | – Avoidance of mechanical stress and trigger factors – Topical treatment as for extragenital psoriasis (typically glucocorticoid/calcineurin inhibitors) |

Footnote: Common differential diagnoses of vulvar pruritus. VIN =vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

[Source 3 ]Infections

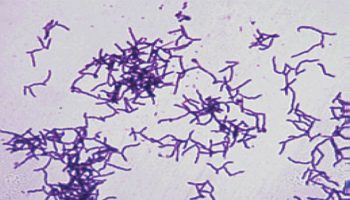

Candida albicans infection (vulvovaginal thrush) is the most important microorganism to consider in a postpubertal woman with vulval itch. Candida can be a cause of napkin dermatitis in babies. Postmenopausal women are unlikely to have Candida albicans infection unless they have diabetes, they are treated with estrogen or antibiotics, or the overgrowth of candida is secondary to an underlying skin disease.

Several less common infections may cause vulval itch:

- Bacterial vaginosis causes a frothy, malodorous discharge, and uncommonly causes vulval itch, possibly as a result of contact dermatitis.

- Genital viral warts (condyloma acuminata) are often itchy.

- Pinworms can reside in the vagina or anus and cause itch when they exit at night.

- Infections that rarely cause vulval itch include cytolytic vaginosis (associated with vaginal lactobacilli) and trichomoniasis.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Genital candidiasis is a common infection and a primary cause of vulvar pruritus, accounting for 35% to 40% of cases 7 2010)). The most common pathogens are Candida albicans (>90%) and Candida glabrata (approx. 2%). 75% of women will have at least one episode of vulvovaginal candidiasis during their lifetime and about 8% will have chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis (at least 4 recurrences/year) 8. Treatment recommendations for acute/chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis are shown in Figure 2 and the Table 1.

Compared to Candida albicans-induced vulvovaginal candidiasis, the clinical signs and symptoms of Candida glabrata-induced vulvovaginal candidiasis are generally milder. Other characteristic features of Candida glabrata-induced vulvovaginal candidiasis include absence of leukocytosis and pseudomycelium formation in the wet preparation as well as production of less vaginal discharge 9. The recommended treatment for Candida glabrata-induced vulvovaginal candidiasis is still an oral dose of 800 mg fluconazole for 2 to 3 weeks 10. Given the rapid development of resistance in recent years, which is primarily attributable to the genetic variability of the pathogen at doses of less than 800 mg fluconazole, satisfactory long-term treatment has increasingly become a challenge 11. Today, fluconazole-sensitive strains are only occasionally encountered in clinical practice and the remaining strains cannot be treated with the triazole derivatives voriconazole or posaconazole either, because of additional cross-resistances. For this reason, it is necessary to use echinocandins for the systemic treatment of Candida glabrata, a new class of antifungal agents which includes, besides caspofungin and anidulafungin, also micafungin, the currently preferred agent 9.

In a randomized controlled trial with 531 patients with invasive candidiasis, micafungin (100 mg/day or 2 mg/kg body weight per day) was as effective (89.6% success rate in both groups) as liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) (3 mg/kg body weight), but caused fewer adverse events 12. While echinocandin class antifungal agents have been available for the treatment of esophageal and invasive candidiasis and other indications since the approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2001 13, no high-quality study data have yet become available to support their use in the treatment of chronic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. For this reason, micafungin, an expensive drug which is given intravenously, has not been approved for the treatment of vaginal mycosis, even though it has been shown to be highly effective against Candida glabrata 14. First promising treatment concepts favor a systemic treatment approach consisting of a 15-day treatment with 150 mg micafungin intravenously/day in combination with ciclopirox olamine cream and nystatin vaginal ovules 9. Treatment strategies commonly recommended in other countries, such as boric acid vaginal suppositories (600 mg) or flucytosine 17%, are not available in Germany. However, because of their increased toxicity, their use is also not recommended 10.

The importance of the human vaginal microbiome—i.e. the totality of all microorganisms present on the vaginal mucosa—in the pathogenesis of vulvar pruritus, especially if the itching is caused by chronic recurrent fungal infections, remains the subject of controversy in the current literature. Compared to the intestinal and oral microbiota, the vaginal microbiome shows less diversity, with 100 to 200 different species 15. The range of species changes several times over the course of a lifetime due to variations in hormone levels. The composition of the vaginal microbiome is influenced by genetic factors, among others, and shows ethnic differences. In more than 70% of cases, the natural colonization of the vagina is dominated by lactobacilli (primarily Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus jensenii, and Lactobacillus iners) 16. By acidifying the vagina and producing antimicrobial substances, such as lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide, lactobacilli protect against the adhesion of facultative pathogens 17.

Since 2008, research on the microorganisms inhabiting the human body has been carried out by the Human Microbiome Project and the Vaginal Microbiome Project of the National Institute of Health (NIH) 15. While more recent studies have demonstrated a causal relationship between changes in the composition of the vaginal microbiota and an increased risk of infection 18, no significant difference was found in a study comparing the dominant Lactobacillus species in women with vulvovaginal candidiasis and without vulvovaginal candidiasis 19. Despite the lack of convincing long-term data regarding the therapeutic targets, it appears that the use of probiotics reduces the vulvovaginal candidiasis recurrence rate 17. For example, in first clinical studies women with chronic recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis were treated with 250g yoghurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus over a period of 6 months. The number of new vulvovaginal Candida infections was 2.5 in the control arm versus 0.38 in the treatment arm 20. Preparation of wet-mount slides continues to be the most important diagnostic test to differentiate between normal and abnormal composition of the vaginal microbiome. It is supplemented by a microbiological culture. In addition, modern sequencing techniques, such as next-generation sequencing, allow for a much more differentiated interpretation and have the potential to become the foundation of our future understanding of the genital tract’s colonization by a wide variety of species of microorganisms.

In Germany, patients with recurrent episodes of vaginitis and vulvovaginal candidiasis are sometimes offered immunization with inactivated lactobacilli of various species 3. The aim of this immunization is to induce specific antibodies against aberrant strains in the Döderlein’s flora which do not contribute to the normal vaginal milieu. At the same time, this treatment aims to achieve regeneration of the affected vaginal flora and restoration of the normal vaginal pH and consequently a general enhancement of local vaginal immunity 3. The recommended regimen consists of basic immunization with 3 doses at 2-week intervals and a booster dose after 6 to 12 months. The primary indication is bacterial vaginosis. The available studies showed a significant reduction in recurrence rate by up to 80% 21. Taking into account cross-protection mechanisms, therapeutic benefits are also expected in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, based on the available data on the use of this approach in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis, the benefit of immunization treatment for this condition is still uncertain 3. Thus, it should only be used in addition to antifungal treatment.

Inflammatory skin condition

Irritant contact dermatitis is the most common cause of an itchy vulva at all ages. It can be acute, relapsing or chronic. It may be due to various reasons, including:

- Age-related prepubertal or postmenopausal lack of estrogen

- Underlying tendency to atopic dermatitis

- Scratching and rubbing

- Friction from skin folds, clothing, activity, or sexual intercourse

- Moisture due to occlusive underwear

- Urine and feces

- Soap or harsh cleanser

- Frequent washing

- Inappropriate or unnecessary chemical applications, including lubricants, over-the-counter or prescribed medications

- Normal, excessive or infected vaginal secretions.

A severe vulval itch may be due to:

- Lichen simplex

- Lichen sclerosus

- Lichen planus.

Other common skin disorders that may cause vulval itch include:

- Psoriasis

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Allergic contact dermatitis. Potential vulval allergens include:

- Methylisothiazolinone, a preservative in moist wipes

- Various textile dyes in underwear

- Fragrance in a douche or antiperspirant

- Rubber accelerants in condom, menstrual cup or underwear

- Adhesives in pads, pantyliners and tampons.

- Irritant or allergic contact urticaria

- Latex rubber and semen are potential causes of contact urticaria.

- Dermographism

- Folliculitis.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is the most common dermatosis of the vulva associated with itching. It often takes a relapsing chronic course and is considered to be a facultative precancerous condition which can develop into squamous cell carcinoma 22. The cause of lichen sclerosus is still not fully understood. Currently, a multifactorial etiology is assumed, primarily driven by genetic and immunological factors. Evidence in support of genetic causes of lichen sclerosus include familial aggregation in up to 17% of cases 23, significant correlation of lichen sclerosus with Human Leucocyte Antigen (HLA)-A28 or HLA-B44 24 and the presence of HLA-DQ7 in 66% of the affected women 25.

In addition to the immunological aspects of lichen sclerosus pathogenesis, which appears to involve a local cell-mediated dermal response to an antigen which has not yet been identified with certainty 26, a preponderance of cytotoxic CD8+ and CD57+ lymphocytes was found in the inflammatory cells present in lichenoid lesions—similar to the proliferation of CD8+ and CD57+ lymphocytes in chronic antigen-mediated inflammatory reactions 27. Furthermore, 15% to 34% of patients with lichen sclerosus have T-cell-mediated autoimmune diseases, such as Hashimoto‘s thyroiditis (12%), alopecia areata (9%) and vitiligo (6%) 28.

In a study with 350 lichen sclerosus patients, 21.5% of patients had one or more autoimmune diseases, 21% had a family history of autoimmune disease and 42% had autoantibodies in titers of >1:20 29. The assumption of an autoimmune pathogenesis of lichen sclerosus is also supported by data from an English study which detected IgG autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein-1 (ECM1) in the serum of 67% of patients compared to 7% in the control group 30. Nevertheless, the existence of an lichen sclerosus-specific antibody cannot be concluded from these study results. The identified antibodies to extracellular matrix proteins are more likely a phenomenon secondary to tissue destruction (e28). Further studies found autoantibodies to the basal membrane proteins BP180 and BP320 31 and thyroid autoantibodies in 30% to 80% and 9% of patients, respectively 28. Even though the precise mechanisms underlying the synthesis of these antibodies are not fully understood, these results indicate that lichen sclerosus is caused by a humoral autoimmune reaction 32.

In addition, infections with Borrelia burgdorferi 33, human papillomavirus (HPV) 34 and Epstein-Barr-Virus 35, as well as local effects, such as Koebner phenomenon, are being discussed as possible causes of lichen sclerosus 36.

Application of ultrapotent topical corticosteroids, such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment for initially 3 months, remains the first-line treatment for genital lichen sclerosus 37. This should usually be followed by life-long reduced-dose maintenance therapy. Both the therapeutic effectiveness and the cancer risk-reducing effect of corticosteroids have repeatedly demonstrated been in various studies 38. In refractory patients, an off-label treatment attempt with calcineurin inhibitors, such as 1% pimecrolimus and 0.03%/0.1% tacrolimus, can be made 39.

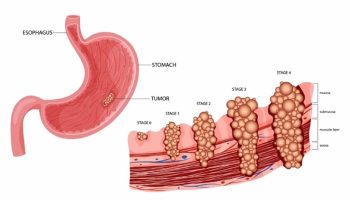

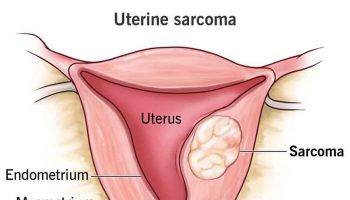

Neoplasm

Benign and malignant neoplastic disorders of the vulva are often asymptomatic in their early stages, but they can cause itch. The most common cancerous lesions are:

- Squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL), also known as vulval intraepithelial neoplasia or VIN.

- Extramammary Paget disease

- Invasive vulval cancer (squamous cell carcinoma)

Neuropathy

Neuropathy should be considered as a cause of vulval itch if there are no signs of infection or skin disease apart from lichen simplex — which can be secondary to a pruritic neuropathy — especially if vulvodynia is present. The neuropathy may be caused by injury, surgery or disease locally (pudendal entrapment), within the pelvis or in the spine.

Vulval itch prevention

A vulval itch cannot always be prevented, depending on its cause. However, vulval health is optimized by the nonspecific measures described below.

Nonspecific treatment

- Avoid irritants such as bubble bath, OTC (over-the-counter) preparations, wet wipes and perfumed sanitary towels around the vulval area

- Minimize scratching or rubbing the affected area.

- Wear loose-fitting absorbent underwear and outer clothing.

- Avoiding tight fitting garments and occlusive nylon underwear such as pantyhose may help.

- Select modern absorbent underwear.

- Keep cool, especially at night-time.

- Apply emollients (eg, sorbolene) and barrier preparations (eg, petroleum jelly).

- Hydrocortisone cream can be used safely and purchased without a prescription.

- Don’t use fabric conditioner when washing underwear or use spermicidally-lubricated condoms during sex.

Vulvar itching signs and symptoms

The clinical features depend on the underlying cause of the vulval itch. There may be an obvious or subtle rash or no signs of disease at all.

When assessing the cause, it’s essential to determine the precise location of the symptoms. Itch often only affects one anatomic part of the vulva:

- Convex areas and thighs: irritant contact dermatitis due to urinary incontinence (usually symmetrical incontinence-associated dermatitis) or rarely, allergic contact dermatitis (asymmetrical)

- Flexures: seborrheic dermatitis, nonspecific or candida intertrigo

- Mons pubis: seborrheic dermatitis, folliculitis

- Labia majora: genital psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, lichen simplex (unilateral or bilateral)

- Labia minora: lichen sclerosus, lichen planus

- Vaginal introitus: erosive lichen planus, atrophic vulvovaginitis, vaginal discharge or infection

- Perineum: dermatitis, lichen sclerosus

- Any site: neoplasia

The itch can also involve other adjacent skin of the abdomen, thighs and perianal area.

An examination may reveal healthy skin, scratch marks (excoriations) and the specific features associated with the underlying cause of the itch.

Morphology may be modified according to the site, with minimal scale evident.

- Candida albicans vaginitis causes thick white vaginal discharge, erythema, and oedema; candida vulvitis causes satellite red superficial papules, pustules, desquamation and erosions.

- Candida can also cause subtle fissuring and subclinical dermatitis.

- Viral warts are clustered as soft condylomata.

- Acute irritant contact dermatitis may be shiny or waxy or scald-like.

- Genital or flexural psoriasis has symmetrical circumscribed erythematous plaques, but they are rarely scaly.

- Seborrheic dermatitis presents with salmon pink, poorly defined patches, sometimes with mild exfoliation.

- Allergic contact dermatitis can have varied morphology but tends to be asymmetrical, intermittent.

- Lichen simplex presents as confluent thickened papules with broken off hairs.

- Lichen sclerosus typically has white plaques, ecchymoses and erosions.

- Lichen planus may present as violaceous or hyperpigmented papules with a white reticulated network (thighs), appear similar to lichen sclerosus; erosive lichen planus causes tender well-defined red patches and erosions in the introitus/vagina and is not usually itchy.

- An intraepithelial or invasive squamous lesion should be considered if there is a solitary plaque with irregular shape, structure, surface and colour. Firm or hard consistency and ulceration and bleeding are particularly concerning.

Vulvar itching complications

An itchy vulva can result in a lot of psychological distress and sleeplessness. Scratching injures the skin, which can lead to pain and secondary bacterial infection.

Vulvar itching diagnosis

The cause or causes of an itchy vulva may be diagnosed through careful history (include genitourinary and musculoskeletal systems) and examination of the vulva.

In patients experiencing genital itching, the medical history should be taken in a systematic manner (see Figure 2 above), covering the following aspects:

- Confirm that the woman is complaining of vulval itch, not vulval pain.

- Symptom duration (acute/chronic)

- Localization (local/generalized)

- Intensity (scale 1–10)

- Pre-existing systemic disorders (e.g. autoimmune disease or diabetes mellitus)

- Pre-existing disorders (e.g. skin disorders, vaginal discharge, menopause or menopausal symptoms)

- Ameliorating/aggravating modulators (e.g., hygiene practices)

- Previous treatments (e.g., self-administered treatments for example, antifungal creams).

- Since the skin in the genital area is influenced by sex hormones, the question whether hormonal medications, such as contraceptives, are taken is also an important part of the clinical history.

- Assess the impact on the patient’s quality of life, including psychosexual issues and sleep patterns. Consider blood tests and vaginal swabs to exclude infections 4.

A full skin examination may reveal a skin condition or disease in another site that gives a clue to why the vulva is itchy.

- Examine the vulval area for signs of infection and dermatological problems (for example, dermatitis, lichen sclerosus) 40.

- Bacterial and viral swabs of the affected area and the vagina may be taken for microbiological examination.

- Skin biopsy of the area affected by itch or visible skin condition may be necessary to determine its exact nature. Sometimes several biopsies may be taken.

- Patch tests are sometimes performed to see whether any contact allergy is present.

Nomenclature of vulvar changes (morphology) according to the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC)

Definitions of primary lesion types

- Macule = small (<1.5 cm) discolored, flat, non-palpable area

- Patch = large (>1.5 cm) discolored, flat, non-palpable area

- Papule = small (<1.5 cm) elevated and palpable lesion

- Plaque = large (>1.5 cm) elevated, palpable and flat-topped lesion

- Nodule = large papule (>1.5 cm), often hemispherical or poorly demarcated; on the surface; cystic or solid lesion

- Vesicle = small (<0.5 cm) blister containing clear fluid

- Bulla = large (>0.5 cm) blister containing clear fluid

- Pustule = pus-filled blister; content is white or yellow

Definitions of secondary morphology presentation (develops from the primary lesion by proliferative transformation, regression or healing)

- Eczema = Inflammatory, non-infectious intolerance reaction characterized by the presence of itchy, poorly demarcated red plaques with minor evidence of microvasculation and/or (more frequently) subsequent surface disruption

- Lichenification = Thickening of the tissue and increased prominence of skin markings, with or without scaling, bright red, dusky red, white or skin-colored.

- Excoriation = Substance defect of the skin extending into the dermis (often scratch marks)

- Purpura = Multiple smaller capillary hemorrhages in the skin, subcutis or mucosa

- Scarring = Replacement tissue after wound healing; often white, fibrous, poorly vascularized

- Erosion = A shallow defect in the skin/mucosa with absence of epidermis/epithelium; the dermis is intact

- Fissure = A thin, linear erosion of the skin/mucosa

- Ulcer = Deeper defect of the skin; absence of the epidermis and some, or all, of the dermis

Suspicion of neoplasia

- Gross neoplasia, ulcer, necrosis, hemorrhage, exophytic lesion, hyperkeratosis with/without white, gray, reddish brown discoloration

- Hyperkeratotic lesions which cannot be wiped off

- Leukoplakia

- Fissures

- Erosions

- Ulcers

During the inspection of the external genitalia, attention should be paid to superficial skin changes, such as erosions or plaques. Besides discolorations and abnormalities of the skin markings, the margins and configurations of the lesions noted should also be taken into account. The classification of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (https://www.issvd.org/) is a tool to categorize the morphological (shape/form) features which has been shown to be particularly useful. Using this classification system, the range of potential differential diagnoses can be narrowed down.

In patients with refractory candidiasis/infection, microbiological swap tests, culture-based tests, and amplification techniques may be needed to confirm the diagnosis. For a more detailed assessment of the vulva, it is recommended to perform a vulvoscopy as this allows to exam the skin of the vulva under 7x to 30x magnification. 5% acetic acid is applied to aid visualization of suspicions areas. Findings suspicious of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)/invasive lesions as well as unclear or refractory vulvar skin changes are indications for a 4–6 mm punch biopsy which can usually be performed without difficulty under local anesthesia. In addition to the examination of the vulva, inspection of both groins, the anal fold and, in some cases, the entire integument is indicated as it may yield important clues about the underlying cause of the clinical signs and symptoms.

Vulvar itching treatment

Vulvar itching treatment involves correct diagnosis and treating any underlying cause. If no cause is identified, offer an emollient to apply directly to the vulval area, and to use as a soap substitute.

Consider using a sedating antihistamine (for example. chlorphenamine) if nocturnal itching is a problem. If symptoms persist, consider the use of short-term (one to two weeks), mild potency corticosteroid cream (hydrocortisone 1%).

Experts recommends potent corticosteroids should only be used if a woman has been advised by a specialist or there is a strong suspicion of lichen sclerosus. A trial may be initiated in primary care while awaiting specialist review.

The conditions causing an itchy vulva often require specific treatment. For example:

- Topical and oral antifungal or antibiotic for an infection

- Topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors for inflammatory disease

- Oral antihistamines for contact urticaria

- Surgery for neoplasia

- Tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake agents, and anticonvulsants for neuropathic symptoms.

Nonspecific treatment

- Avoid irritants such as bubble bath, OTC (over-the-counter) preparations, wet wipes and perfumed sanitary towels around the vulval area

- Minimize scratching or rubbing the affected area.

- Wear loose-fitting absorbent underwear and outer clothing.

- Avoiding tight fitting garments and occlusive nylon underwear such as pantyhose may help.

- Select modern absorbent underwear.

- Keep cool, especially at night-time.

- Apply emollients (eg, sorbolene) and barrier preparations (eg, petroleum jelly).

- Hydrocortisone cream can be used safely and purchased without a prescription.

- Don’t use fabric conditioner when washing underwear or use spermicidally-lubricated condoms during sex.

Contact dermatitis occurs quite readily when inflamed skin affects the genital area.

- Wash once or twice daily with lukewarm water alone or use a soap-free cleanser.

- Do not use leave-on moist wipes, antiperspirants or other cosmetics in the vulva.

- Insert tampons with care or use reusable silicone menstrual cups.

- Change sanitary pads, pantiliners and incontinence products frequently.

- Avoid riding bicycles or horses.

Tricyclic antidepressants may be prescribed to control intractable itch, even in the absence of a defined neuropathy.

Pruritus vulvae treatment

In patients with persistent, pruritus vulvae (idiopathic vulvar pruritus), as a rule the following treatment option should be considered:

- Local cooling

- Evening dosing of an antihistamine, e.g. hydroxyzine 41

- Anticonvulsants, in the form of gabapentin 42

- Antidepressants, such as doxepin, sertraline, mirtazapine 42

- Opioid antagonists, e.g. naltrexone 43

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) 44

- Acupuncture 45.

Furthermore, it is crucial to ask questions regarding potential psychosocial and psychosexual causes and, if any, to address these in collaboration with psychologists, psychotherapists and specialists in sexual medicine 3.

Vulvar itching prognosis

Vulval itch is usually a minor, short-lived nuisance. However, some women may suffer from a vulval itch for years, and may only receive temporary relief from treatment if not correctly diagnosed.

- Itchy vulva. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/the-itchy-vulva[↩]

- Fischer GO. The commonest causes of symptomatic vulvar disease: a dermatologist’s perspective. Australas J Dermatol 1996; 37(1): 12-8.[↩]

- Woelber L, Prieske K, Mendling W, Schmalfeldt B, Tietz HJ, Jaeger A. Vulvar pruritus-Causes, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Approach. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;116(8):126–133. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0126 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7081372[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Doxanakis A, Bradshaw C, Fairley C, Pokorny CS. Vulval itch: all that itches is not thrush. Med Today 2004; 5(6): 54-63.[↩][↩]

- NICE. Referral guidelines for suspected cancer: quick reference guide. CG27, London, NICE, 2005.[↩]

- Edwards S, Handfield-Jones S, Gull S. National guideline on the management of vulval conditions. Int J STD AIDS 2002; 13(6): 411-5.[↩]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG), Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Infektionen und Infektionsimmunologie in der Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (AGII), Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG), Deutschsprachige Mykologische Gesellschaft (DMyKG) Die Vulvovaginalkandidose AWMF 013/004 (S1+IDA[↩]

- Mendling W. Dyspareunie, Vulvodynie und Vestibulodynie: Schmerzen statt Lust. Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe. 2019;24:24–27.[↩]

- Tietz HJ. [Candida glabrata: pathogenicity and therapy update] Hautarzt. 2012;63:868–871.[↩][↩][↩]

- Mendling W. Guideline: Vulvovaginal candidosis (AWMF 015/072), S2k (excluding chronic mucocutaneous candidosis) Mycoses. 2015;58 S1:1–15.[↩][↩]

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 Update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e1–e50[↩]

- Kuse E-R, Chetchotisakd P, Cunha C, et al. Micafungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for candidaemia and invasive candidosis: a phase III randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2007;369:1519–1527.[↩]

- Perlin DS. Current perspectives on echinocandin class drugs. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:441–457.[↩]

- Oliveira ER, Fothergill A, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Redding SW. Antifungal susceptibility testing of micafungin against candida glabrata isolates. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:457–459.[↩]

- Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Knight R, et al. The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214.[↩][↩]

- Petricevic L. Das vaginale Mikrobiom. Der Gynäkologe. 2019;52:10–15.[↩]

- Steyer GE. Das vaginale Mikrobiom. EHK. 2017;66:44–50.[↩][↩]

- Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Girerd PH, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. A new era of the vaginal microbiome: advances using next-generation sequencing. Chem Biodivers. 2012;9:965–976.[↩]

- Sobel JD, Chaim W. Vaginal microbiology of women with acute recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2497–2499.[↩]

- Mendling W. Schwiertz A, editor. Vaginal microbiota Microbiota of the human body: implications in health and disease. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2016:83–93.[↩]

- Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Cubie H, et al. Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human papillomavirus: the HART study. Lancet. 2003;362:1871–1876.[↩]

- Kirtschig G, Becker K, Günthert A, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline on (anogenital) Lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:e1–e43.[↩]

- Sherman V, McPherson T, Baldo M, Salim A, Gao X, Wojnarowska F. The high rate of familial lichen sclerosus suggests a genetic contribution: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1031–1034.[↩]

- Purcell KG, Spencer LV, Simpson PM, Helman SW, Oldfather JW, Fowler JF Jr. HLA antigens in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1043–1045.[↩]

- Powell J, Wojnarowska F, Winsey S, Marren P, Welsh K. Lichen sclerosus premenarche: autoimmunity and immunogenetics. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:481–484.[↩]

- Gross T, Wagner A, Ugurel S, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. Identification of TIA-1+ and Granzyme B+ cytotoxic T cells in Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Dermatology. 2001;202:198–202.[↩]

- Carlson JA, Grabowski R, Chichester P, Paunovich E, Malfetano J. Comparative immunophenotypic study of lichen sclerosus: Epidermotropic CD57+ lymphocytes are numerous—implications for pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:7–16.[↩]

- Kreuter A, Kryvosheyeva Y, Terras S, et al. Association of autoimmune diseases with lichen sclerosus in 532 male and female patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:238–241.[↩][↩]

- Thomas RHM, Ridley CM, Mcgibbon DH, Black MM. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity—a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41–46.[↩]

- Oyama N, Chan I, Neill SM, et al. Autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. The Lancet. 2003;362:118–123.[↩]

- Strittmatter HJ, Hengge UR, Blecken SR. Calcineurin antagonists in vulvar lichen sclerosus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274:266–270.[↩]

- Chan I, Oyama N, Neill SM, Wojnarowska F, Black MM, McGrath JA. Characterization of IgG autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 in lichen sclerosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:499–504.[↩]

- Eisendle K, Grabner T, Kutzner H, Zelger B. Possible role of borreliaburgdorferi sensu lato infection in lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:591–598.[↩]

- Powell J, Strauss S, Gray J, Wojnarowska F. Genital carriage of human papilloma virus (HPV) DNA in prepubertal girls with and without vulval disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:191–194.[↩]

- Aidé S, Lattario FR, Almeida G, do Val IC, da Costa Carvalho M. Epstein-barr virus and human papillomavirus infection in vulvar lichen sclerosus. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010;14:319–322.[↩]

- Farrell AM, Dean D, Millard PR, Charnock FM, Wojnarowska F. Cytokine alterations in lichen sclerosus: an immunohistochemical study. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:931–940.[↩]

- Schwegler J, Schwarz J, Eulenburg C, et al. Health-related quality of life and patient-defined benefit of clobetasol 005% in women with chronic lichen sclerosus of the vulva. Dermatology. 2011;223:152–160.[↩]

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatology. 2015;151:1061–1067.[↩]

- Luesley D, Downey G. Topical tacrolimus in the management of lichen sclerosus. BJOG. 2006;113:832–834.[↩]

- Canavan TP, Cohen, D. Vulvar cancer. Am Fam Physician 2002; 66(7): 1269-74.[↩]

- van der Meijden WI, Boffa MJ, Ter Harmsel WA, et al. European guideline for the management of vulval conditions 2016. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:925–941.[↩]

- Yosipovitch G, Bernhard JD. Chronic pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1625–1634.[↩][↩]

- Mattle V, Seeber B, Ruth-Egger S, Zervomanolakis I, Wildt L. Die Behandlung des therapierefraktären Pruritus vulvae mit Naltrexon, einem spezifischen Opiatantagonisten. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2008;68[↩]

- Mohammad Ali BM, Hegab DS, El Saadany HM. Use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for chronic pruritus. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:210–215.[↩]

- Yu C, Zhang P, Lv Z-T, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture in itch: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015[↩]