What is Wellens syndrome

Wellens syndrome is also referred to as left anterior descending coronary artery T-wave syndrome 1. Wellens’ syndrome is a pre-infarction stage of significant proximal left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis and may lead to extensive anterior wall myocardial infarction without timely intervention 2. Wellens syndrome was first described in the early 1980s by de Zwaan, Wellens, and colleagues, who identified a subset of patients with unstable angina who had specific precordial T-wave changes and subsequently developed a large anterior wall myocardial infarction (heart attack) 3. Wellens syndrome refers to these specific electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities in the precordial T-wave segment, which are associated with critical stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery.

Wellens syndrome was reported in 26% (35/137) of patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing coronary angiogram 4. T wave changes in Wellens’ syndrome are associated with widely scattered electrical and mechanical activities (QTc dispersion) in myocardium and severe myocardial dysfunction 4. Wellens’ syndrome can be identified as 2 patterns on EKG 5:

- Pattern A has biphasic T waves in V2–V3 (25%) and

- Pattern B has symmetric and deeply inverted T waves in chest leads (75%).

The diagnostic criteria for Wellens’ syndrome includes the presence of pattern A or pattern B in EKG plus a history of angina, pain-free period, little or no elevation of ST segment, no Q waves in chest leads, and normal or minimal elevation of cardiac enzymes 6. The T wave inversion has 69% sensitivity, 89% specificity, and 86% positive predictive value for significant left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion 7. Even in the challenging situations with pre-existing left bundle branch block (LBBB), Wellens’ EKG patterns can be used to detect acute coronary syndrome 8.

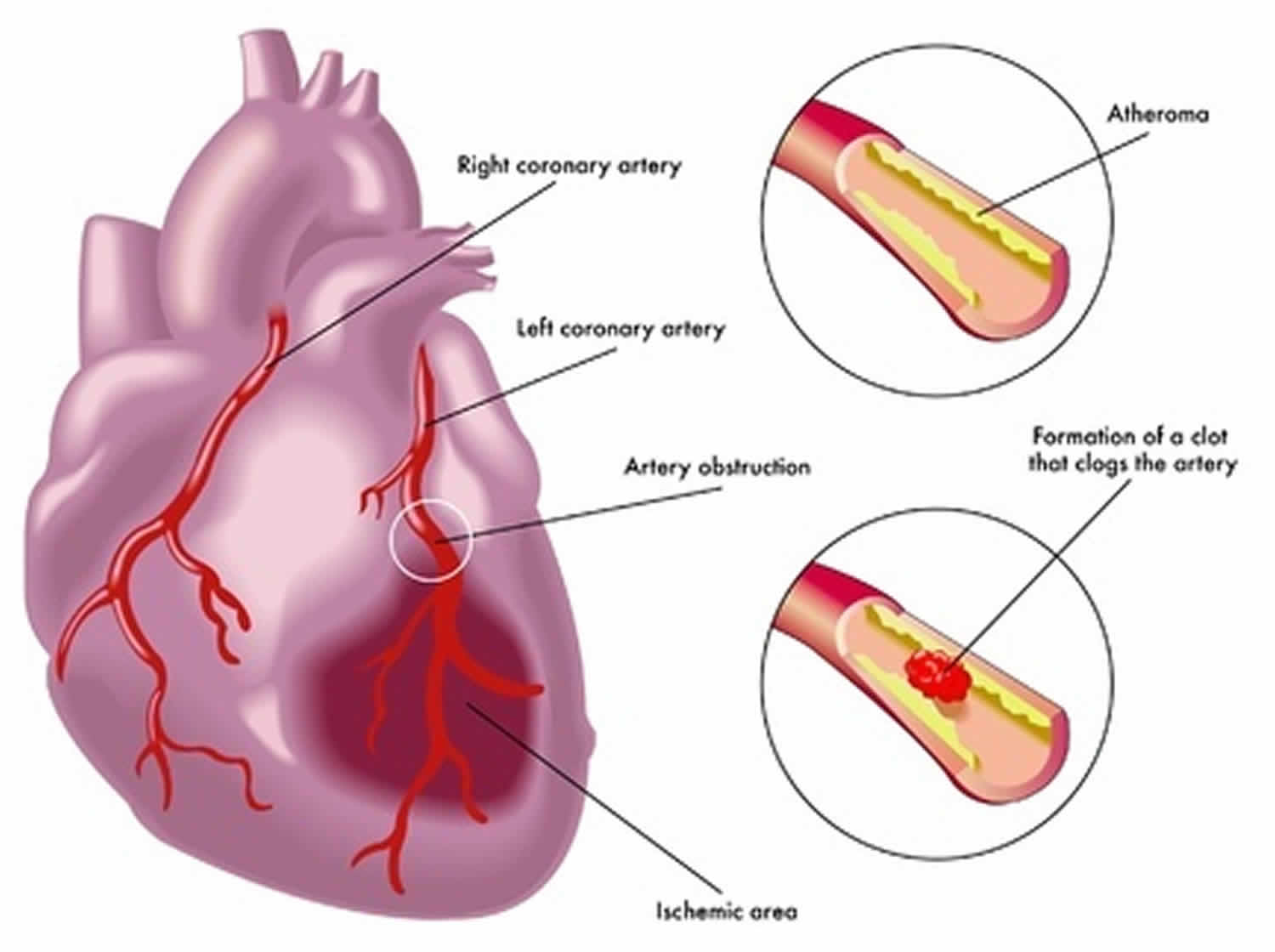

Wellens syndrome represents critical stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. The left anterior descending coronary artery arises from the left coronary artery and travels in the interventricular groove along the anterior portion of the heart to the apex. This groove is situated between the right and left ventricles of the heart. The left anterior descending coronary artery gives rise to 2 main branches, the diagonals and the septal perforators 9.

A lesion in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery can have severe consequences, as suggested by the common nickname given to this lesion: “widow maker.” The left anterior descending coronary artery supplies the anterior wall of the heart, including both ventricles, as well as the septum. An occlusion in this vessel can result in serious ventricular dysfunction, thus placing the patient at serious risk for congestive heart failure (CHF) and death.

The differential diagnoses of T wave inversions are acute coronary syndrome (ACS), pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, left ventricular hypertrophy, juvenile T wave, Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome, and digoxin toxicity 10. Unlike the regular practice in patients with possible ischemic chest pains, cardiac stress testing is contraindicated in Wellens’ syndrome patients because it can precipitate acute myocardial infarction 11. When Wellens’ sign is discovered in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, a low threshold should be maintained for prompt coronary angiography to determine treatment options 11. If there is significant proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery occlusion, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery should be performed to prevent extensive anterior myocardial infarction. When solely managed with medical therapy, 75% of Wellens’ syndrome patients developed extensive anterior wall infarction within 1 week 12.

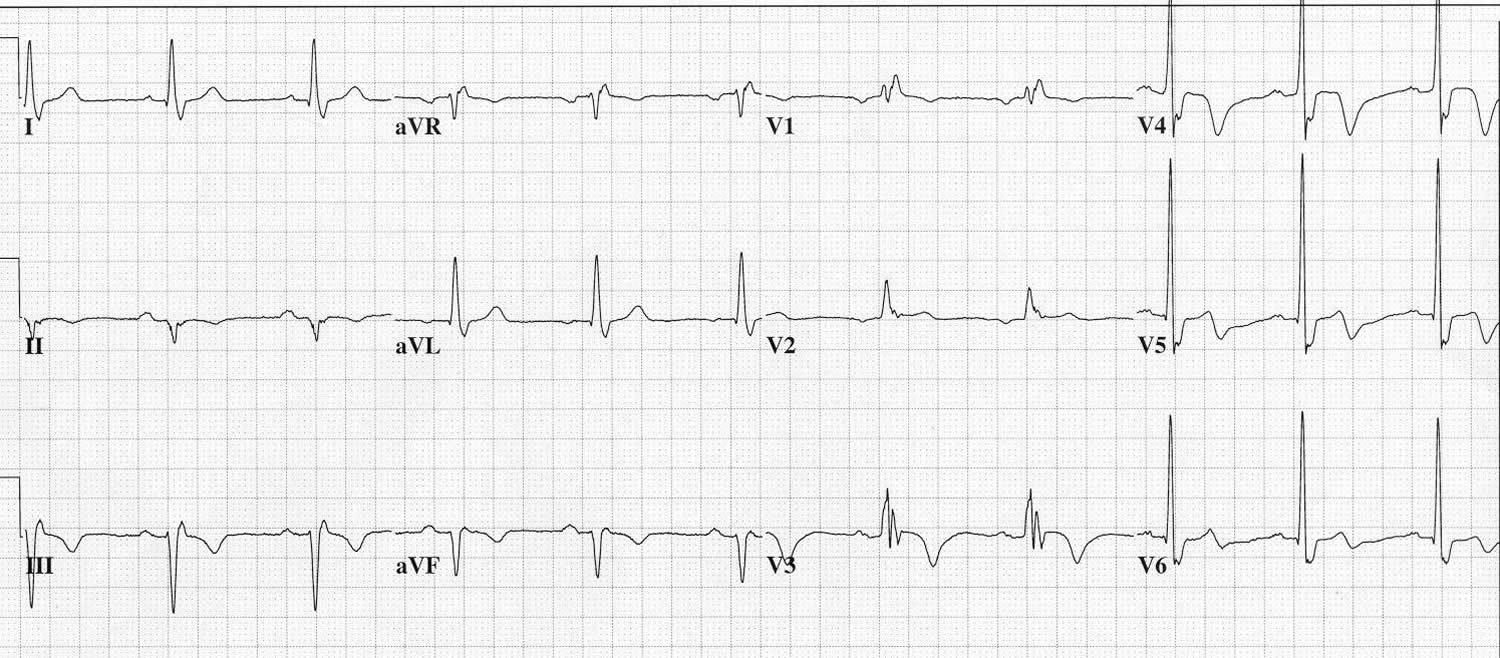

Figure 1. Wellens syndrome ECG

Footnote: Classic Wellens syndrome T-wave changes. ECG was repeated on a patient who came in to the emergency department with 8/10 chest pain after becoming pain free secondary to medications. Notice the deep T waves in V3-V5 and slight biphasic T wave in V6 in this chest pain– free ECG. The patient had negative cardiac enzyme levels and later had a stent placed in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery.

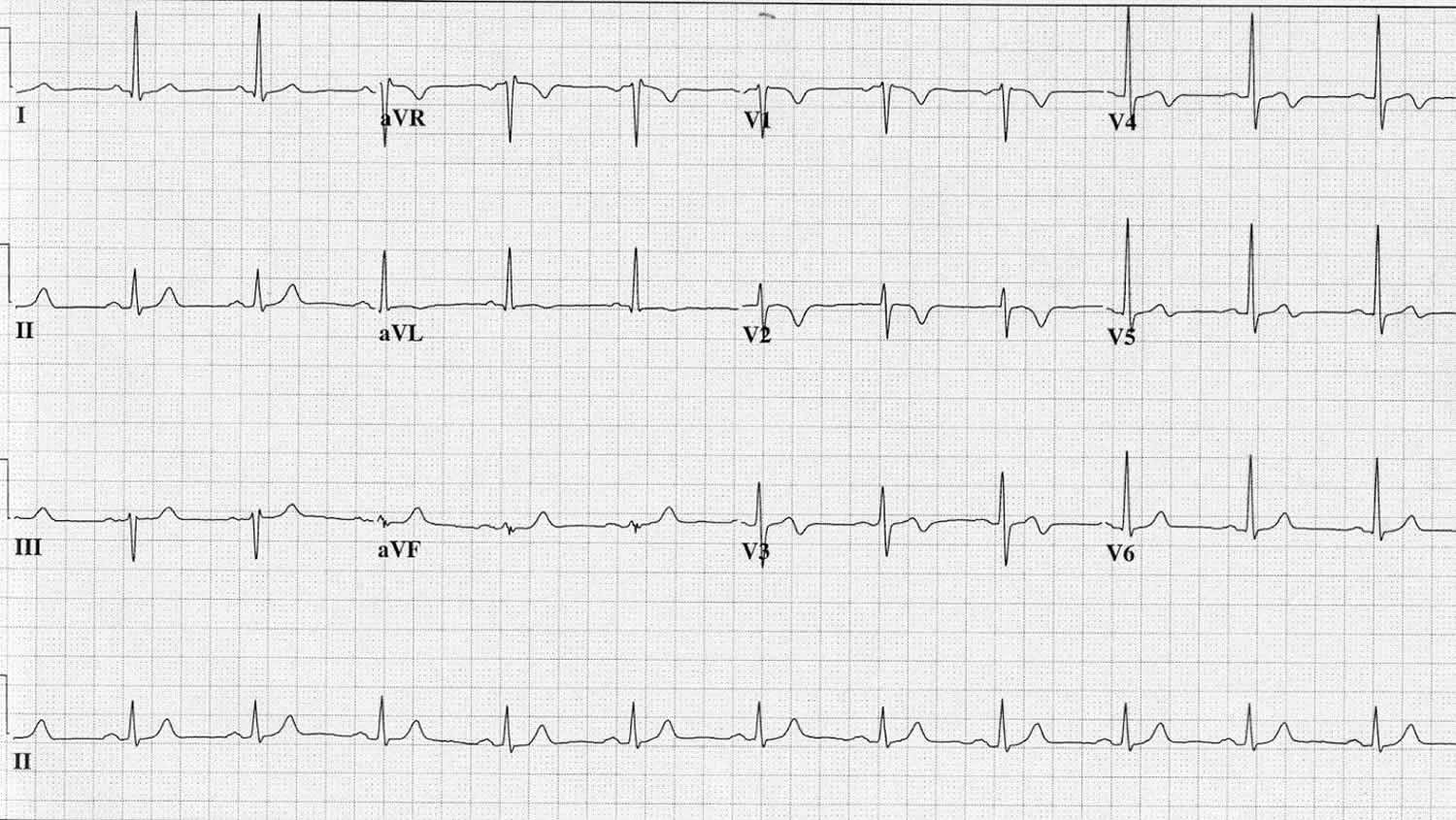

[Source 13 ]Figure 2. Wellens syndrome ECG

Footnote: Pain-free ECG of a 57-year-old patient who presented with 4/10 pressurelike chest pain. Notice after the patient was treated with medications and pain subsided, the ECG shows T-wave inversion in V2 and biphasic T waves in V3-V5. This more closely resembles the less common presentation of Wellens syndrome with a biphasic T-wave pattern. This patient had a cardiac catheterization that showed a subtotal occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery, which was stented, and the patient did well.

[Source 13 ]Wellens syndrome criteria

Wellens syndrome criteria include the following 13:

- Characteristic T-wave changes

- History of anginal chest pain

- Normal or minimally elevated cardiac enzyme levels

- ECG without Q waves, without significant ST-segment elevation, and with normal precordial R-wave progression

The characteristic ECG pattern of Wellens syndrome is relatively common in patients who have symptoms consistent with unstable angina. Of patients admitted with unstable angina, this ECG pattern is present in 14-18% 14.

Recognition of this ECG abnormality is of paramount importance because this syndrome represents a preinfarction stage of coronary artery disease (CAD) that often progresses to a devastating anterior wall myocardial infarction (heart attack).

Wellens syndrome represents critical proximal left anterior descending coronary artery disease; accordingly, its natural progression leads to anterior wall myocardial infarction. This progression is so likely that medical management alone is not enough to stop the natural process. Evolution to an anterior wall myocardial infarction is rapid, with a mean time of 8.5 days from the onset of Wellens syndrome to infarction 15.

If anterior wall myocardial infarction occurs, there is the potential for substantial morbidity or mortality. Thus, it is of utmost importance to recognize this pattern early.

Wellens syndrome causes

Wellens syndrome is a preinfarction stage of coronary artery disease 13. Thus, the causes of Wellens syndrome are similar to the conditions that cause coronary artery disease, including the following:

- Atherosclerotic plaque

- Coronary artery vasospasm (cocaine is one possible cause)

- Increased cardiac demand

- Generalized hypoxia

Risk factors for Wellens syndrome are essentially those of coronary artery disease and include the following:

- Smoking history

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Increased age

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Hyperlipidemia

- Metabolic syndrome

- Family history of premature heart disease

- Occupational stress

Wellens syndrome symptoms

Wellens syndrome represents stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD), and patients typically present with symptoms or complaints consistent with coronary artery disease (CAD). Generally, the history is most consistent with unstable angina. Angina can have varying presentations, but the classic presentation includes the following complaints:

- Chest pain described as pressure, tightness, or heaviness

- Pain that is typically induced by activity and relieved by rest

- Radiation of pain to the jaw, shoulder, or neck

- May experience multiple associated symptoms, including (but not limited to) diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue

Elderly, diabetic, and female patients are more likely to present with atypical symptoms.

Wellens syndrome diagnosis

Physical examination does not provide any indicators that would give the examiner strong grounds for suspecting Wellens syndrome specifically. However, the results of the patient’s examination may show evidence of ongoing ischemic injury (eg, congestive heart failure).

In addition, most of the electrocardiographic (ECG) changes are recognized when the patient is pain-free, which again underscores the importance of a repeat pain-free ECG in the emergency department.

Potential diagnostic pitfalls with Wellens syndrome include the following:

- Failing to recognize Wellens syndrome T-wave changes on electrocardiography (ECG)

- Ordering a stress test without recognizing risks; this may provoke a large anterior wall myocardial infarction (MI) 16

- Underestimating the seriousness of the ECG finding in a pain-free patient

- Failing to properly admit or consult cardiology on patients with the characteristic ECG changes

Laboratory studies

The following laboratory studies may be indicated as adjunctive tests in patients with suspected coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndrome, and Wellens syndrome:

- Complete blood count (CBC) – To ensure that anemia is not precipitating the angina, red blood cell (RBC) transfusions may be necessary

- Basic metabolic profile – This includes electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and glucose levels

- Typing and screening – These are indicated if immediate cardiac catheterization is planned

- D-dimer, international normalized ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT) – These are ordered only as medically necessary

- Cardiac biomarkers – In Wellens syndrome, cardiac biomarkers can be falsely reassuring, in that they are typically normal or only minimally elevated; only 12% of patients with this syndrome have elevated cardiac biomarker levels, and these are always less than twice the upper limit of normal, in the absence of myocardial infarction (MI) 14.

- Angiography has demonstrated that 100% of patients with Wellens syndrome will have 50% or greater stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery 17. More specifically, 83% will have the lesion proximal to the second septal perforator 18.

- Stress testing is generally not indicated in patients with this ECG presentation, because it places them at risk for acute anterior wall MI. Ideally, therefore, these patients would bypass stress testing and undergo urgent angiography to determine the extent of disease and potentially provide information about the need for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), or medical management 19. If provocative testing is determined to be necessary, it should be done cautiously and only in close conjunction with a cardiologist 20.

Imaging studies

Chest radiography should be performed to look for side effects of ischemia, such as pulmonary edema. In addition, this test should be performed to help exclude other possible causes of chest pain, such as thoracic aneurysm or dissection, pneumonia, and rib fracture.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest is performed only as indicated to help rule out other causes of chest pain, such as aortic dissection or pulmonary embolus. The value of CT angiography of the chest in the evaluation of chest pain, coronary artery disease, and acute coronary syndrome is currently being investigated.

Electrocardiography

ECG should be performed on any patient with a complaint of chest pain if noncardiac causes cannot be diagnosed by other means, including physical examination. It may be helpful to perform ECG both while the pain is present and after the pain has resolved. The ECG changes seen in Wellens syndrome typically are manifested when the patient is pain-free but usually occur in the context of recent anginal chest pain.

In Wellens syndrome, the ECG pattern shows significant involvement of the T wave, with minimal ST-segment alteration. The ST segments themselves are usually isoelectric, but if they are abnormal, there will be less than 1 mm of elevation, with a high takeoff of the ST segment from the QRS complex. The characteristic ECG changes of this syndrome occur in the T-wave and occur in 2 forms.

The more common of the 2 forms, which occurs 76% of the time, is deep inversion of the T-wave segment in the precordial leads (see Figure 1 above) 21. The ST segment will be straight or concave and will pass into a deep negative T wave at an angle of 60°-90°. The T wave is symmetric. In Wellens syndrome, these changes generally occur in leads V1 -V4 but occasionally may also involve V5 and V6. V1 is involved in approximately 66% of patients, and V4 is involved nearly 75% of the time 22.

The less common of the 2 forms of Wellens syndrome, which occurs in 24% of patients, consists of biphasic T waves (see Figure 2 above), most commonly in leads V2 and V3 but also, on occasion, in leads V1 through V5 or even V6 17.

The characteristic pattern classically presents only during chest pain–free periods. Noticing this pattern is crucial because it is a sign of left anterior descending coronary artery disease. This association underscores the importance of serial ECGs and a pain-free ECG on patients with unstable angina. Because the left anterior descending coronary artery supplies the anterior myocardium, failure to recognize this pattern can result in anterior wall myocardial infarction (MI), significant left ventricular dysfunction, or death.

Reperfusion of the posterior wall following posterior MI leads to a larger T-wave amplitude in the right precordial leads and an even higher T-wave amplitude in leads V2 and V3 23.

Wellens syndrome treatment

A cardiologist should be consulted early in the management of a patient with Wellens syndrome. If the patient remains pain-free, it is appropriate to admit him or her to an internist on a telemetry floor, but the internist should be notified that the patient is at high risk and should not undergo stress testing unless clearly recommended by cardiologists.

If symptoms persist or electrocardiography (ECG) shows evolution into ST-segment elevations, an interventional cardiologist should be consulted immediately. Transfer of these patients to institutions with cardiac catheterization capabilities is generally appropriate.

Because Wellens syndrome occurs because of stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, patients typically complain of chest pain presenting as unstable angina. During episodes of pain, they should be treated in the same manner as any patient experiencing chest pain thought to be cardiac in origin.

Immediate arrangements should be made for transport to the nearest hospital. Careful attention should be paid to the ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation). During transport, efforts should be made to carry out the following:

- Oxygen supplementation

- Assessment of vital signs

- Intravenous (IV) access

- Administration of aspirin

- ECG, if available before arrival at the hospital

- If pain persists, administration of nitroglycerin or morphine, according to local protocols

If Wellens syndrome is identified on an outpatient basis, then arrangements should be made for urgent evaluation. Stress testing should be avoided.

Patients presenting with symptoms consistent with unstable angina should generally receive medications and other therapies and measures that may help prevent myocardial infarction (MI). Usually, these would include the following:

- IV access

- Supplemental oxygen, when appropriate

- ECG (initially) – Serial examinations and pain-free tracings may be helpful

- Telemetry monitoring

- Chest radiography

- Laboratory studies (see Laboratory Studies)

- Aspirin

- Consideration should be given to providing beta-blocker therapy, nitroglycerin, morphine, heparin, clopidogrel, and glycoprotein IIb/IIa inhibitors

Once again, the ECG changes in Wellens syndrome are typically only present when the patient is free of chest pain. Thus, obtaining serial ECGs on patients with unstable angina may be helpful.

Even though the ECG changes may be subtle, it is vital to recognize Wellens syndrome because these patients can rarely undergo stress testing safely 24. Because Wellens syndrome is a sign of a preinfarction stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery, a stress test has the potential to result in acute MI and severe damage to the left ventricle. Therefore, these patients should generally forgo a stress test and instead may undergo angiography to evaluate the need for angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG).

Even with ideal medical management, the natural progression of Wellens syndrome is to acute anterior wall MI. Approximately 75% of patients with Wellens syndrome who receive only medical management and do not undergo revascularization (either through CABG or through angioplasty) will go on to develop extensive anterior wall MI within days 25. Anterior wall MI carries substantial morbidity and mortality: it will result in left ventricular dysfunction and possibly even death.

Thus, patients generally should be medically stabilized if possible while arrangements are made for urgent angiography and revascularization if appropriate.

Further inpatient care for patients with Wellens syndrome includes the following:

- Attempts to keep the patient pain-free

- Provision of a telemetry bed to monitor the patient.

- Consultation with a cardiologist

Medications

The goals of pharmacotherapy are to reduce morbidity and prevent complications. Agents used in the management of Wellens syndrome include salicylates, antihypertensive drugs, antianginal drugs, antiplatelet drugs, analgesics, low-molecular-weight heparins, antiarrhythmic drugs, and anticoagulants.

- Nisbet BC, Zlupko G. Repeat Wellens’ syndrome: case report of critical proximal left anterior descending artery restenosis. J Emerg Med. 2010 Sep. 39(3):305-8 https://www.jem-journal.com/article/S0736-4679(07)00894-3/fulltext[↩]

- Kyaw K, Latt H, Aung SSM, Tun NM, Phoo WY, Yin HH. Atypical Presentation of Acute Coronary Syndrome and Importance of Wellens’ Syndrome. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:199–202. Published 2018 Feb 22. doi:10.12659/AJCR.907992 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5829624[↩]

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1982 Apr. 103(4 Pt 2):730-6[↩]

- T-wave changes in patients with Wellens syndrome are associated with increased myocardial mechanical and electrical dispersion. Stankovic I, Kafedzic S, Janicijevic A, Cvjetan R, Vulovic T, Jankovic M, Ilic I, Putnikovic B, Neskovic AN. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017 Oct; 33(10):1541-1549.[↩][↩]

- Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Wellens HJ. Am Heart J. 1982 Apr; 103(4 Pt 2):730-6.[↩]

- Mead NE, O’Keefe KP. Wellen’s syndrome: An ominous EKG pattern. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2(3):206–8[↩]

- Haines DE, Raabe DS, Gundel WD. Anatomic and prognostic significance of new T-wave inversion in unstable angina. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52(1):14–18.[↩]

- Grautoff S. Wellens’ syndrome can indicate high-grade LAD stenosis in case of left bundle branch block. Herzschrittmacherther Elektrophysiol. 2017;28(1):57–59.[↩]

- Moore KL, Dalley AF. Thorax. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 4th ed. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. 135.[↩]

- Ozdemir S, Ozturk TC, Eyinc Y, et al. Wellens’ syndrome – report of two cases. Turk J Emerg Med. 2015;15(4):179–81.[↩]

- Stankovic I, Kafedzic S, Janicijevic A, et al. T-wave changes in patients with Wellens syndrome are associated with increased myocardial mechanical and electrical dispersion. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33(10):1541–49[↩][↩]

- de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1982;103(4):730–36[↩]

- Wellens Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1512230-overview[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Janssen JH, et al. Angiographic and clinical characteristics of patients with unstable angina showing an ECG pattern indicating critical narrowing of the proximal LAD coronary artery. Am Heart J. 1989 Mar. 117(3):657-65.[↩][↩]

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1982 Apr. 103(4 Pt 2):730-6.[↩]

- Patel K, Alattar F, Koneru J, Shamoon F. ST-elevation myocardial infarction after pharmacologic Persantine stress test in a patient with Wellens’ syndrome. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2014. 2014:530451[↩]

- de Zwaan C, Bar FW, Janssen JH, et al. Angiographic and clinical characteristics of patients with unstable angina showing an ECG pattern indicating critical narrowing of the proximal LAD coronary artery. Am Heart J. 1989 Mar. 117(3):657-65[↩][↩]

- Rhinehardt J, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of Wellens’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2002 Nov. 20(7):638-43.[↩]

- Tatli E, Aktoz M, Buyuklu M, Altun A. Wellens’ syndrome: the electrocardiographic finding that is seen as unimportant. Cardiol J. 2009. 16(1):73-5. [↩]

- Narasimhan S, Robinson GM. Wellens syndrome: a combined variant. J Postgrad Med. 2004 Jan-Mar. 50(1):73-4[↩]

- Tandy TK, Bottomy DP, Lewis JG. Wellens’ syndrome. Ann Emerg Med. 1999 Mar. 33(3):347-51[↩]

- Rhinehardt J, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of Wellens’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2002 Nov. 20(7):638-43[↩]

- Driver BE, Shroff GR, Smith SW. Posterior reperfusion T-waves: Wellens’ syndrome of the posterior wall. Emerg Med J. 2017 Feb. 34(2):119-23[↩]

- Sowers N. Harbinger of infarction: Wellens syndrome electrocardiographic abnormalities in the emergency department. Can Fam Physician. 2013 Apr. 59(4):365-6[↩]

- Movahed MR. Wellens’ syndrome or inverted U-waves?. Clin Cardiol. 2008 Mar. 31(3):133-4.[↩]