What is a Calorie

Calories are units representing the ability of food to be converted by the body into energy. All food contains calories, and we need a certain amount of calories each day.

- Large calorie (Cal) is the energy needed to increase 1 kg of water by 1°C at a pressure of 1 atmosphere.

- Large calorie (Cal) is also called Food calorie and is used as a unit of food energy.

- 1 Large Calorie (1 kilocalories) = 4.184 kilojoules (kJ)

- 2000 Calories = 8368 kilojoules (kJ)

Because how much calories you eat and what food groups you need are highly dependent on your age, sex, and your level of physical activity. For the most accurate way calculate how much food and calories you need to eat per day from each food group, Go to >>>>>

- To find out about your body mass index (BMI), you can use a FREE online BMI calculators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – for Adults 1 and for Children 2

- To find out What and How Much To Eat, you can use a FREE, award-winning, state-of-the-art, online diet and activity tracking tool called SuperTracker 3 from the United States Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion 3. This free application empowers you to build a healthier diet, manage weight, and reduce your risk of chronic diet-related diseases. You can use SuperTracker 3 to determine what and how much to eat; track foods, physical activities, and weight; and personalize with goal setting, virtual coaching, and journaling.

SuperTracker website 3

- To find out about how many calories you should eat to lose weight according to your weight, age, sex, height and physical activity, you can use a FREE online app Body Weight Planner 4

- To find out about the 5 Food Groups you should have on your plate for a meal, you can use a FREE online app ChooseMyPlate 5

Calories are the energy in food. Your body has a constant demand for energy and uses the calories from food to keep functioning. Energy from calories fuels your every action, from sleeping to marathon running.

It is true that all “calories” have the same amount of energy. One dietary Calorie contains 4184 Joules of energy. In that respect, a calorie is a calorie. But when it comes to your body, things are not that simple. Looking only at calories ignores the metabolic effects of each calorie; the source of the calorie changes how you digest it and how you retrieve energy from it. The human body is a highly complex biochemical system with elaborate processes that regulate energy balance. This is because some foods provide not only calories but also other ingredients that also are critically important, such as vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and others. When a food provides primarily calories, and little else of value to our health, we say that food has “empty calories.”

Examples include beverages like sugary soda, and foods like buttery pastries. They provide little health value. You can get all the calories you need from foods other than these-foods that contain other healthful ingredients. Another problem with foods said to contain “empty calories” is that they usually contain lots of calories-more than we need to attain or sustain a healthy weight.

Counting calories alone doesn’t work because ultimately it matters where those calories come from; this matters more than the number of calories ingested.

Carbohydrates, fats and proteins are the types of nutrients that contain calories and are the main energy sources for your body. Regardless of where they come from, the calories you eat are either converted to physical energy or stored within your body as fat.

Your weight is a balancing act, but the equation is simple: If you eat more calories than you burn, you gain weight.

Because 3,500 calories equals about 1 pound (0.45 kilogram) of fat, you need to burn 3,500 calories more than you take in to lose 1 pound.

So, in general, if you cut 500 calories from your typical diet each day, you’d lose about 1 pound a week (500 calories x 7 days = 3,500 calories). A weight loss of 1 to 2 pounds a week is the typical recommendation. Although that may seem like a slow pace for weight loss, it’s more likely to help you maintain your weight loss for the long term. Remember that 1 pound (0.45 kilogram) of fat contains 3,500 calories. So to lose 1 pound a week, you need to burn 500 more calories than you eat each day (500 calories x 7 days = 3,500 calories).

However, it isn’t quite this simple,because you usually lose a combination of fat, lean tissue and water. Also, if you lose a lot of weight very quickly, you may not lose as much fat as you would with a more modest rate of weight loss. Instead, you might lose water weight or even lean tissue, since it’s hard to burn that many fat calories in a short period.

What is Low Calorie Diet

A low calorie diet (LCD) limits calories, but not as much as a very low calorie diet (VLCD). A typical low calorie diet (LCD) may provide:

- 1,000–1,200 calories/day for a woman

- 1,200–1,600 calories/day for a man

A low calorie diet is a diet with a reduction in calorie intake without deprivation of essential nutrients.

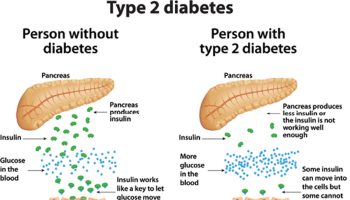

Calorie restriction without malnutrition is the most powerful nutritional intervention that has consistently been shown to increase maximal and average lifespan in a variety of organisms, including yeasts, worms, flies, spiders, rotifers, fish and rodents 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Far from merely stretching the life of an old, ill and weak animal, calorie restriction extends longevity by preventing chronic diseases, and by preserving metabolic and biological functions at more youthful-like state 11, 12, 13. In rodents, the calorie restriction-mediated preventive effects are widespread with major reductions in the occurrence and/or progression of cancer, nephropathy, cardiomyopathy, obesity, type 2 diabetes, neuro-degenerative disease, and several autoimmune diseases 14, 15, 16. Moreover, unlike ad-libitum fed rodents, ~30% of the calorie restriction rodents die in old age without any pathological sign of disease 17. Likewise, 25 to 50% of the longevous Ames/Snell dwarf mice and growth hormone receptor knock-out mice expire without pathological evidence of disease severe enough to be recorded as the cause of death 18, 19, suggesting that in mammals the occurrence of lethal chronic disease can be completely prevented by dietary and genetic manipulations that down-regulate the key cellular nutrient-sensing pathways 6. However, whether or not calorie restriction with adequate nutrition will significantly slow aging and extend lifespan in non-human primates, and most importantly in human beings, is not yet clear.

Whether or not calorie restriction without malnutrition will extend lifespan in humans is not known yet, but accumulating data indicate that moderate calorie restriction with adequate nutrition has a powerful protective effect against the development of obesity, type 2 diabetes, inflammation, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, which are major causes of morbidity, disability and mortality 20. Accordingly, Lloyd-Jones and colleagues found that in men and women from the Framingham Heart Study with normal cardiovascular risk profile at age 50 (i.e. total glycemia <125 mg/dl, blood pressure <120/80 mmHg, cholesterol <180 mg/dl, BMI <25 kg/m2 and no smoke) the lifetime probability of developing an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease was very low (i.e., 6.7% versus 59.5% in participants with ≥2 cardiometabolic risk factors) and average lifespan markedly longer (i.e. >39 versus 29.5 years in participants with ≥2 cardiometabolic risk factors) 21. In humans calorie restriction without malnutrition also results in a consistent reduction in circulating levels of growth factors, anabolic hormones, adipokines and inflammatory cytokines, which are associated with an increased risk of some of the most common types of cancer 22.

In terms of calorie reduction, we know that one pound equals 3,500 calories. By reducing daily calorie intake by 500 to 1,000 calories, it is reasonable to expect a weight loss of 1 to 2 pounds/week.

The number of calories may be adjusted based on your age, weight, and how active you are. A low calorie diet usually consists of regular foods, but could also include meal replacements. As a result, you may find this type of diet much easier to follow than a very low calorie diet. In the long term, low calorie diets have been found to lead to the same amount of weight loss as very low calorie diets.

In 2011, a Diabetes UK research trial at Newcastle University 23 tested a low-calorie diet in 11 people with Type 2 diabetes, which helped us to understand how Type 2 diabetes can be put into remission. After the 8-week diet, volunteers had reduced the amount of fat in their liver and pancreas. This helped to restore their insulin production and put their Type 2 diabetes into remission. Three months later, some had put weight back on, but most still had normal blood glucose control. This study was only a first step. It was designed to tell us about the underlying biology of Type 2 diabetes, and it followed the participants for only three months.

Another study, published in 2016, confirmed these findings and showed (in 30 people) that Type 2 diabetes could be kept in remission 6 months after the low-calorie diet was completed. It also suggested that the diet was effective in people that had had Type 2 diabetes for up to 10 years.

Both of these studies were very small, and were carried out in a research environment. We don’t yet understand the long-term effects of these diets, or how a low-calorie diet might be used to bring about and maintain Type 2 diabetes remission in a real-life setting, as part of routine general practice care.

Currently a new research is underway in Scotland and Tyneside (UK) called the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial, where 20-65 year olds who are overweight and have been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in the last six years, will be randomised to receive either low calorie diet for between 8 and 20 weeks or the current best-available Type 2 diabetes care. This study will last until October 2018 and results will be released once all of the data has been analysed probably early 2019 23.

In the meantime there’s been a lot of buzz on the internet about using a low-calorie diet to live longer. A new study of overweight people who cut their calories by 25% for 6 months found some promising lab results that have been linked to longevity 24. The results aren’t enough for any major conclusions, but they point the way toward longer studies to see if low-calorie diets can really slow the aging process in people.

In that longevity study with low calorie diet, participants were randomly divided into 4 groups:

- One group stayed on a diet to maintain their pre-study weight.

- A calorie-restriction group ate 25% less calories.

- A calorie-restriction with exercise group ate 12.5% less calories but exercised to burn 12.5% more.

- A very low-calorie diet group ate 890 calories a day until they lost 15% of their weight. They then followed a weight-maintenance diet to hold the lower weight.

Fasting insulin levels were significantly lower in all three groups on the restricted-calorie diets. Core body temperature was reduced in both the calorie-restriction and calorie-restriction with exercise groups. The low-calorie diets may also affect some other measurements of metabolism that have been linked with living longer and aging. The calorie restriction significantly lowered several predictors of cardiovascular disease compared to the control group:

- Decreasing average blood pressure by 4 percent

- Decreasing total cholesterol by 6 percent.

- Levels of HDL (“good”) cholesterol were increased.

- Calorie restriction caused a 47-percent reduction in levels of C-reactive protein, an inflammatory factor linked to cardiovascular disease.

- It also markedly decreased insulin resistance, which is an indicator of diabetes risk.

- T3, a marker of thyroid hormone activity, decreased in the calorie restriction group by more than 20 percent, while remaining within the normal range. This is of interest since some studies suggest that lower thyroid activity may be associated with longer life span.

No increased risk of serious adverse clinical events was reported. However, a few participants developed transient anemia and greater-than-expected decreases in bone density given their degree of weight loss, reinforcing the importance of clinical monitoring during calorie restriction.

Calorie restriction without malnutrition has been consistently shown to increase longevity in a number of animal models, including yeast, C. elegans, and mice 6. However, the effect of calorie restriction on the lifespan of nonhuman primates remains controversial and may be heavily influenced by dietary composition 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30.

The lifespan extension associated with calorie restriction in model organisms is believed to operate through its effects on growth hormone (GH) and growth hormone receptor (GHR), leading to subsequent deficiencies in IGF-1 and insulin levels and signaling 6. The effect of the insulin/IGF-1 pathway on longevity was first described in C. elegans by showing that mutations in the insulin/IGF-1 receptor or in the downstream age-1 gene caused a several-fold increase in lifespan 31. Other studies revealed that mutations in genes functioning in insulin/IGF-1 signaling, but also activated independently of insulin/IGF-1, including TOR-S6K and RAS-cAMP-PKA, promoted aging in multiple model organisms, thus providing evidence for the conserved regulation of aging by pro-growth nutrient signaling pathways 32. Not surprisingly, in mice, growth hormone receptor deficiency (GHRD) or growth hormone deficiency (GHD), both of which display low levels of IGF-1 and insulin, cause the strongest lifespan extension but also reduction of age-related pathologies including cancer and insulin resistance/diabetes 33, 34, 35. Recently, this study 36 showed showed that humans with growth hormone receptor deficiency (GHRD), also exhibiting major deficiencies in serum IGF-1 and insulin levels, displayed no cancer mortality or diabetes. Despite having a higher prevalence of obesity, combined deaths from cardiac disease and stroke in this group were similar to those in their relatives 37. Similar protection from cancer was also reported in a study that surveyed 230 growth hormone receptor deficiency 38.

Protein restriction or restriction of particular amino acids, such as methionine and tryptophan, may explain part of the effects of calorie restriction and growth hormone receptor deficiency mutations on longevity and disease risk, since protein restriction is sufficient to reduce IGF-1 levels and can reduce cancer incidence or increase longevity in model organisms, independently of calorie intake 39, 40, 41.

Low Calorie Diet and Weight Loss

In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2009, followed 811 overweight adults over 2 years 42, who were prescribed Low Calorie Diets (a deficit of 750 kcal per day from baseline, as calculated from the person’s resting energy expenditure and activity level) and all the low calorie diets should include 8% or less of saturated fat, at least 20 g of dietary fiber per day, and 150 mg or less of cholesterol per 1000 kcal). Carbohydrate-rich foods with a low glycemic index were recommended in each diet. Each participant’s caloric prescription represented one of the four diets:

- Fat 20%, Protein 15% and Carbohydrate 65% (Low-fat and Average-protein and High carb)

- Fat 20%, Protein 25% and Carbohydrate 55% (Low-fat and High-protein and Average carb)

- Fat 40%, Protein 15% and Carbohydrate 45% (High-fat and Average-protein and Average carb)

- Fat 40%, Protein 25% and Carbohydrate 35% (High-fat and High-protein and Low carb)

- All participants’ goal for physical activity was 90 minutes of moderate exercise per week. Participation in exercise was monitored by questionnaire and by the online self-monitoring tool.

Group sessions were held once a week, 3 of every 4 weeks during the first 6 months and 2 of every 4 weeks from 6 months to 2 years; individual sessions were held every 8 weeks for the entire 2 years. Daily meal plans in 2-week blocks were provided. Participants were instructed to record their food and beverage intake in a daily food diary and in a web-based self-monitoring tool that provided information on how closely their daily food intake met the goals for macronutrients and energy. Behavioral counseling was integrated into the group and individual sessions to promote adherence to the assigned diets. Contact among the groups was avoided.

At 6 months, participants assigned to each diet had lost an average of 6 kg, which represented 7% of their initial weight; they began to regain weight after 12 months.

- By 2 years, weight loss remained similar in those who were assigned to a diet with 15% protein and those assigned to a diet with 25% protein (3.0 and 3.6 kg, respectively); in those assigned to a diet with 20% fat and those assigned to a diet with 40% fat (3.3 kg for both groups); and in those assigned to a diet with 65% carbohydrates and those assigned to a diet with 35% carbohydrates (2.9 and 3.4 kg, respectively).

- Among the 80% of participants who completed the trial, the average weight loss was 4 kg; 14 to 15% of the participants had a reduction of at least 10% of their initial body weight. Satiety, hunger, satisfaction with the diet, and attendance at group sessions were similar for all diets; attendance was strongly associated with weight loss (0.2 kg per session attended). The diets improved lipid-related risk factors and fasting insulin levels.

Conclusions: Reduced-calorie diets result in clinically meaningful weight loss regardless of which macronutrients they emphasize. All of the diets resulted in meaningful weight loss, despite the differences in macronutrient composition 42.

The study also found that the more group counseling sessions participants attended, the more weight they lost, and the less weight they regained. This supports the idea that not only is what you eat important, but behavioral, psychological, and social factors are important for weight loss as well 42.

Low Calorie Diet Foods

- Protein.

Protein should be no more than 15 percent of total calories and should be derived from plant sources and lean sources of animal protein.

Lean plant proteins include dry peas, beans, legumes, and soy protein (tofu). Lean animal protein includes lean cuts of meat, poultry, seafood, and low fat dairy (milk, yogurt, cheese,and cottage cheese).

- Carbohydrate and Fiber.

Dietary carbohydrate should be approximately 55 percent or more of total calories and should be rich in complex carbohydrates from different vegetables, fruits, and whole grains—all good sources of vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

• A diet high in all types of fiber may aid in weight management by promoting satiety at lower levels of calorie and fat intake.

• Some authorities recommend 20 to 30 grams of fiber daily, with an upper limit of 35 grams. A diet rich in soluble fiber, including oat bran, legumes, barley, and most fruits and vegetables, may be effective in reducing blood cholesterol levels. A diet high in all types of fiber may also aid in weight management by promoting satiety at lower calorie and fat levels.

- Calcium.

During weight loss, attention should be given to maintaining an adequate intake of vitamins and minerals, particularly calcium. Maintenance of the recommended calcium intake of 1,000 to 1,500 mg/day is especially important for women who may be at risk of osteoporosis.

- Total Fat.

Fat-modified foods can be a great help to those who are trying to lose weight, but only if the low-fat food is also low in calories and the lost calories are not compensated for by eating larger quantities of these low-fat foods or other foods. Reducing fat can be an important way to save calories, but many low-fat products in the store have the same number of calories as the regular variety. This is why it is important

to read the food label to compare fat as well as calories.

| Breakfast | Energy (Kcal) | Fat (GM) | %Fat | Exchange for: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-wheat bread, 1 med. slice | 70 | 1.2 | 15 | (1 Bread/Starch) |

| Jelly, regular, 2 tsp | 30 | 0 | 0 | (½ Fruit) |

| Cereal, shredded wheat, ½ C | 104 | 1 | 4 | (1 Bread/Starch) |

| Milk, 1%, 1 C | 102 | 3 | 23 | (1 Milk) |

| Orange juice, ¾ C | 78 | 0 | 0 | (1½ Fruit) |

| Coffee, regular, 1 C | 5 | 0 | 0 | (Free) |

| Breakfast Total | 389 | 5.2 | 10 |

| Lunch | Energy (Kcal) | Fat (GM) | %Fat | Exchange for: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roast beef sandwich | ||||

| Whole-wheat bread, 2 med. slices | 139 | 2.4 | 15 | (2 Bread/Starch) |

| Lean roast beef, unseasoned, 2 oz | 60 | 1.5 | 23 | (2 Lean Protein) |

| Lettuce, 1 leaf | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tomato, 3 med. slices | 10 | 0 | 0 | (1 Vegetable) |

| Mayonnaise, low-calorie, 1 tsp | 15 | 1.7 | 96 | (1⁄3 Fat) |

| Apple, 1 med. | 80 | 0 | 0 | (1 Fruit) |

| Water, 1 C | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Free) |

| Lunch Total | 305 | 5.6 | 16 |

| Dinner | Energy (Kcal) | Fat (GM) | %Fat | Exchange for: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon, 2 oz edible | 103 | 5 | 40 | (2 Lean Protein) |

| Vegetable oil, 1½ tsp | 60 | 7 | 100 | (1½ Fat) |

| Baked potato, ¾ med. | 100 | 0 | 0 | (1 Bread/Starch) |

| Margarine, 1 tsp | 34 | 4 | 100 | (1 Fat) |

| Green beans, seasoned with margarine, ½ C | 52 | 2 | 4 | (1 Vegetable) (½ Fat) |

| Carrots, seasoned | 35 | 2 | 0 | (1 Vegetable) |

| White dinner roll, 1 small | 70 | 2 | 26 | (1 Bread/Starch) |

| Iced tea, unsweetened, 1 C | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Free) |

| Water, 2 C | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Free) |

| Dinner Total | 454 | 20 | 39 |

| Snack | Energy (Kcal) | Fat (GM) | %Fat | Exchange for: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popcorn, 2½ C | 69 | 0 | 0 | (1 Bread/Starch) |

| Margarine, ¾ tsp | 30 | 3 | 100 | (¾ Fat) |

| Grand Total | 1,247 | 34 | 24 |

How Many Calories Do You Need ?

Estimated Calorie Needs per Day, by Age, Sex, and Physical Activity Level

| AGE | Sedentary[a] | Moderately active[b] | Active[c] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| 3 | 1,000 | 1,400 | 1,400 |

| 4 | 1,200 | 1,400 | 1,600 |

| 5 | 1,200 | 1,400 | 1,600 |

| 6 | 1,400 | 1,600 | 1,800 |

| 7 | 1,400 | 1,600 | 1,800 |

| 8 | 1,400 | 1,600 | 2,000 |

| 9 | 1,600 | 1,800 | 2,000 |

| 10 | 1,600 | 1,800 | 2,200 |

| 11 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 2,200 |

| 12 | 1,800 | 2,200 | 2,400 |

| 13 | 2,000 | 2,200 | 2,600 |

| 14 | 2,000 | 2,400 | 2,800 |

| 15 | 2,200 | 2,600 | 3,000 |

| 16 | 2,400 | 2,800 | 3,200 |

| 17 | 2,400 | 2,800 | 3,200 |

| 18 | 2,400 | 2,800 | 3,200 |

| 19-20 | 2,600 | 2,800 | 3,000 |

| 21-25 | 2,400 | 2,800 | 3,000 |

| 26-30 | 2,400 | 2,600 | 3,000 |

| 31-35 | 2,400 | 2,600 | 3,000 |

| 36-40 | 2,400 | 2,600 | 2,800 |

| 41-45 | 2,200 | 2,600 | 2,800 |

| 46-50 | 2,200 | 2,400 | 2,800 |

| 51-55 | 2,200 | 2,400 | 2,800 |

| 56-60 | 2,200 | 2,400 | 2,600 |

| 61-65 | 2,000 | 2,400 | 2,600 |

| 66-70 | 2,000 | 2,200 | 2,600 |

| 71-75 | 2,000 | 2,200 | 2,600 |

| 76 and up | 2,000 | 2,200 | 2,400 |

Notes:

[a] Sedentary means a lifestyle that includes only the physical activity of independent living.[b] Moderately Active means a lifestyle that includes physical activity equivalent to walking about 1.5 to 3 miles perd ay at 3 to 4 miles per hour, in addition to the

activities of independent living.

[c] Active means a lifestyle that includes physical activity equivalent to walking more than 3 miles per day at 3 to 4 miles per hour, in addition to the activities o f

independent living.

[d] Estimates for females do not include women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

(SOURCE: 43)

Balancing Calories

Balancing the calories you eat and drink with the calories burned by being physically active helps to maintain a healthy weight.

Each person uses different amounts of calories doing the same type of activity. In general, heavier people use more calories. Those who weigh less use fewer. Women also probably use fewer.

How much physical activity ? Although any amount of regular physical activity is good for you, aim for at least 150 minutes of physical activity each week. Unless you are already that active, you won’t do that much all at once—10-minute sessions several times a day on most days are fine.

Different foods go through different biochemical pathways, some of which are inefficient and cause energy (calories) to be lost as heat.

You should choose nutrient-dense foods. These foods give you lots of nutrients without a lot of extra calories. Even more important is the fact that different foods and macronutrients have a major effect on the hormones and brain centers that control hunger and eating behavior.

On the other hand, foods that are high in calories for the amount of food are called calorie dense. They may or may not have nutrients. High-calorie foods with little nutritional value, like potato chips, sugar-sweetened drinks, candy, baked goods, and alcoholic beverages, are sometimes called “empty calories.”

Energy density means getting more for your calories.

Energy density is the number of calories (energy) in a given amount (volume) of food. By choosing foods that are low in calories, but high in volume, you can eat more and feel fuller on fewer calories.

Fruits and vegetables are good choices because they tend to be low in energy density and high in volume.

So what about raisins ? They’re actually high in energy density — they pack a lot of calories into a small package. For example, 1/4 cup of raisins has about 100 calories. For about the same number of calories you could have 1 cup of grapes — and get more bite for your calorie buck.

High versus low energy density

Foods high in energy density include fatty foods, such as many fast foods, and foods high in sugar, such as sodas and candies. For example, a small order of fast-food french fries has about 250 calories.

For about the same calorie count, you could have heaping helpings of fresh fruits and vegetables — such as this salad made with 10 cups of spinach, 1 1/2 cups of strawberries and a small apple.

And with fresh fruits and vegetables, you get a plethora of valuable nutrients — not just empty calories. These foods also take longer to eat and are filling, which helps curb your hunger.

Another way to think about the idea of nutrient-dense and calorie-dense foods is to look at a variety of foods that all provide the same calories. Which would make a better snack for you ?

Let’s say that you wanted to have a snack that contained about 100 calories. You might choose one of these:

- 7- or 8-inch banana,

- Two ounces baked chicken breast with no skin,

- Three cups low-fat popcorn,

- Two regular chocolate-sandwich cookies,

- Half cup low-fat ice cream,

- One scrambled large egg cooked with fat,

- 20 peanuts,

- Half of the average-size candy bar.

Although these examples all have about 100 calories, there are some big differences:

- Banana, chicken, peanuts, or egg are more nutrient dense.

- Popcorn or chicken are likely to help you feel more satisfied.

- Chicken, peanuts, or egg have more protein.

- Cookies, candy, and ice cream have more added sugars.

Can choosing a nutrient-dense food instead of a calorie-dense food really make a difference ? Here are some examples of nutrient-dense choices side by side with similar foods that are not nutrient-dense, have more calories, or both.

A) Hamburger patty, 4 oz. precooked, extra lean ground beef

167 calories

B) Hamburger patty, 4 oz. precooked, regular ground beef

235 calories

A) Large apple, 8 oz.

110 calories

B) Apple pie, eighth of a 2-crust 9″ pie

356 calories

A) Two slices of 100% whole wheat bread, 1 oz. each

138 calories

B) Medium croissant, 2 oz.

231 calories

A) Medium baked potato with peel, 2 tablespoons low-fat sour cream

203 calories

B) French fries, one medium fast-food order

457 calories

A) Roasted chicken breast, skinless (3 oz.)

141 calories

B) Fried chicken wings with skin and batter, (3 oz.)

479 calories

A) A candy bar

280 calories

B) A pita bread stuffed with low-fat chicken salad

280 calories

Healthy eating:

- Emphasizes vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products.

- Includes lean meat, poultry, fish, cooked dry beans and peas, eggs, and nuts.

- Is low in saturated fats, trans fats, salt, and added sugars.

- Balances the calories from foods and beverages with calories burned through physical activity so that you can maintain a healthy weight.

- BMI Calculator Adults. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_BMI/english_bmi_calculator/bmi_calculator.html[↩]

- BMI Calculator Children. https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpabmi/Calculator.aspx[↩]

- https://supertracker.usda.gov/[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Body Weight Planner. https://www.supertracker.usda.gov/bwp/index.html[↩]

- ChooseMyPlate. https://www.choosemyplate.gov/[↩]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Dietary Restriction, Growth Factors and Aging: from yeast to humans. Science (New York, NY). 2010;328(5976):321-326. doi:10.1126/science.1172539. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3607354/[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Greer EL, Brunet A. Different dietary restriction regimens extend lifespan by both independent and overlapping genetic pathways in C. elegans. Aging Cell. 2009;8(2):113-127. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00459.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2680339/[↩]

- Kennedy BK, Steffen KK, Kaeberlein M. Ruminations on dietary restriction and aging. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1323–1328. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17396225[↩]

- Mair W, Dillin A. Aging and survival: the genetics of life span extension by dietary restriction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:727–754. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18373439[↩]

- Masoro EJ. Overview of caloric restriction and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:913–922. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15885745[↩]

- Martin B, Mattson MP, Maudsley S. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting: Two potential diets for successful brain aging. Ageing research reviews. 2006;5(3):332-353. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2006.04.002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2622429/[↩]

- Wang C, Maddick M, Miwa S, et al. Adult-onset, short-term dietary restriction reduces cell senescence in mice. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2(9):555-566. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2984605/[↩]

- Ye J, Keller JN. Regulation of energy metabolism by inflammation: A feedback response in obesity and calorie restriction. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2(6):361-368. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2919256/[↩]

- Weindruch R, Naylor PH, Goldstein AL, Walford RL. Influences of aging and dietary restriction on serum thymosin alpha 1 levels in mice. J Gerontol. 1988;43:B40–42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3346517[↩]

- Ahmet I, Tae H-J, de Cabo R, Lakatta EG, Talan MI. Effects of Calorie Restriction on Cardioprotection and Cardiovascular Health. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51(2):263-271. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.04.015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3138119/[↩]

- Qin W, Zhao W, Ho L, et al. Regulation of forkhead transcription factor FoxO3a contributes to calorie restriction-induced prevention of Alzheimer’s disease-type amyloid neuropathology and spatial memory deterioration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1147:335-347. doi:10.1196/annals.1427.024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2605640/[↩]

- Shimokawa I, Higami Y, Hubbard GB, McMahan CA, Masoro EJ, Yu BP. Diet and the suitability of the male Fischer 344 rat as a model for aging research. J Gerontol. 1993;48:B27–32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8418135[↩]

- Ikeno Y, Bronson RT, Hubbard GB, Lee S, Bartke A. Delayed occurrence of fatal neoplastic diseases in ames dwarf mice: correlation to extended longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:291–296. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12663691[↩]

- Vergara M, Smith-Wheelock M, Harper JM, Sigler R, Miller RA. Hormone-Treated Snell Dwarf Mice Regain Fertility But Remain Long Lived and Disease Resistant. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2004;59(12):1244-1250. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2924623/[↩]

- Fontana L, Meyer TE, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(17):6659-6663. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308291101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC404101/[↩]

- Yu BP, Masoro EJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PW, Wolf PA, Levy D. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006;113:791–798. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/6/791.long[↩]

- Longo VD, Fontana L. Calorie restriction and cancer prevention: metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2010;31(2):89-98. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2829867/[↩]

- Diabetes UK. Research spotlight – low-calorie diet for Type 2 diabetes. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/Research/Research-round-up/Research-spotlight/Research-spotlight-low-calorie-liquid-diet/[↩][↩]

- J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2015) 70 (9): 1097-1104. A 2-Year Randomized Controlled Trial of Human Caloric Restriction: Feasibility and Effects on Predictors of Health Span and Longevity. https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/70/9/1097/2949096/A-2-Year-Randomized-Controlled-Trial-of-Human[↩]

- Mercken EM, Crosby SD, Lamming DW, et al. Calorie restriction in humans inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway and induces a younger transcription profile. Aging cell. 2013;12(4):645-651. doi:10.1111/acel.12088. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3714316/[↩]

- Stein PK, Soare A, Meyer TE, Cangemi R, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Caloric restriction may reverse age-related autonomic decline in humans. Aging cell. 2012;11(4):644-650. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00825.x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3598611/[↩]

- Mattison JA, Roth GS, Beasley TM, et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys: the NIA study. Nature. 2012;489(7415):10.1038/nature11432. doi:10.1038/nature11432. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3832985/[↩]

- Aging, adiposity, and calorie restriction. Fontana, L. and Klein, S. JAMA. 2007; 297: 986–994. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17341713[↩]

- Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science (New York, NY). 2009;325(5937):201-204. doi:10.1126/science.1173635. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2812811/[↩]

- Cava E, Fontana L. Will calorie restriction work in humans? Aging (Albany NY). 2013;5(7):507-514. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3765579/[↩]

- The genetics of ageing. Kenyon, C.J. Nature. 2010; 464: 504–512. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20336132[↩]

- The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Kenyon, C. Cell. 2005; 120: 449–460. http://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(05)00110-8[↩]

- Brown-Borg HM, Bartke A. GH and IGF1: Roles in Energy Metabolism of Long-Living GH Mutant Mice. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2012;67A(6):652-660. doi:10.1093/gerona/gls086. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3348496/[↩]

- Dwarf mice and the ageing process. Brown-Borg, H.M., Borg, K.E., Meliska, C.J., and Bartke, A. Nature. 1996; 384: 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8900272[↩]

- Masternak MM, Bartke A. Growth hormone, inflammation and aging. Pathobiology of Aging & Age Related Diseases. 2012;2:10.3402/pba.v2i0.17293. doi:10.3402/pba.v2i0.17293. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3417471/[↩]

- Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population .Cell Metabolism Volume 19, Issue 3, p407–417, 4 March 2014. http://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(14)00062-X[↩]

- Guevara-Aguirre J, Balasubramanian P, Guevara-Aguirre M, et al. Growth Hormone Receptor Deficiency is Associated With a Major Reduction in Pro-aging Signaling, Cancer and Diabetes in Humans. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(70):70ra13. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001845. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3357623/[↩]

- Congenital IGF1 deficiency tends to confer protection against post-natal development of malignancies. Steuerman, R., Shevah, O., and Laron, Z. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011; 164: 485–489. http://www.eje-online.org/content/164/4/485.long[↩]

- Fontana L, Adelaiye RM, Rastelli AL, et al. Dietary protein restriction inhibits tumor growth in human xenograft models of prostate and breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2013;4(12):2451-2461. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3926840/[↩]

- Gallinetti J, Harputlugil E, Mitchell JR. Amino acid sensing in dietary-restriction-mediated longevity: roles of signal-transducing kinases GCN2 and TOR. The Biochemical journal. 2013;449(1):1-10. doi:10.1042/BJ20121098. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3695616/[↩]

- Surgical stress resistance induced by single amino acid deprivation requires Gcn2 in mice. Peng, W., Robertson, L., Gallinetti, J., Mejia, P., Vose, S., Charlip, A., Chu, T., and Mitchell, J.R. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012; 4: 18ra11.[↩]

- N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 26;360(9):859-73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19246357[↩][↩][↩]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids.

Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2002.[↩]